Abstract

Cholera is caused only by O1 and O139 Vibrio cholerae strains. For diagnosis, 3 working days are needed for bacterial isolation from human feces and for biochemical characterization. Here we describe the purification of bacterial outer membrane proteins (OMP) from V. cholerae O1 Ogawa, O1 Inaba, and O139 strains, as well as the production of specific antisera and their use for fecal Vibrio antigen detection. Anti-OMP antisera showed very high reactivity and specificity by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and dot-ELISA. An inmunodiagnostic assay for V. cholerae detection was developed; this assay avoids preenrichment and costly equipment and can be used for epidemiological surveillance and clinical diagnosis of cases, considering that prompt and specific identification of bacteria is mandatory in cholera.

Cholera is an acute intestinal disease with watery diarrhea, vomiting, high dehydration, acidosis, and circulation disorders caused by Vibrio cholerae. In case of erratic treatment, death can occur during the first day (12, 13). In spite of the appearance of more than 100 V. cholerae serogroups, only O1 and O139 induce disease (12, 16, 17). Etiological diagnosis of V. cholerae is based on the isolation of the bacteria from human feces and their biochemical characterization (5a, 20). Vomiting material, water sources, and food can also be used to isolate V. cholerae (5a). Cholera is an infection of pandemic magnitude, and thus prompt and specific identification of bacteria is mandatory; nevertheless, routine microbiological and biochemical analyses need 3 working days (5a, 8). In spite of many publications related to immunological and molecular methods for cholera diagnosis (1, 2, 6, 7, 10, 11, 14, 19), most assays require enrichment by previous culture of bacteria, which increases the time needed or involves the use of costly equipment and reagents. In this paper we describe the purification of bacterial outer membrane proteins (OMP) and the production of specific antisera and their use in a detection assay for fecal antigens that does not require preenrichment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Selection and evaluation of bacteria.

Four Vibrio strains were used for antibody production and as controls for the assays: V. cholerae O1 Inaba (CDC13), V. cholerae O1 Ogawa (CDC12), V. cholerae O139, and Vibrio alginolyticus. Bacteria were plated and grown in thiosulfate-citrate-bile salts-sucrose agar (TCBS; Dibico-Mexico) for 18 h at 37°C. Colonies were tested by biochemical methods (5a, 9, 13) and by agglutination using polyclonal antibodies against V. cholerae O1 prepared with Roshka antigens in accordance with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention protocols (20). Other enteric bacteria (Aeromonas caviae, Aeromonas hydrophila, Citrobacter freundii, Enterobacter agglomerans, Enterobacter cloacae, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella oxytoca, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Morganella morganii, Plesiomonas shigelloides, Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Serratia marcescens, Vibrio mimicus, and Vibrio parahaemolyticus) were grown in Trypticase in soybean broth (TSB; Bioxon-Mexico), pooled, and inactivated by boiling for 20 min before using them in immunological assays.

Isolation of OMP.

Vibrios for antibody production were grown in TSB at 37°C for 6 h in a humid chamber; 1 ml was transferred to Erlenmeyer flasks in TSB and grown overnight to induce logarithmic-phase growth. Bacteria were processed as described by Pruzzo et al. (18) and Tarsi and Pruzzo (23). Briefly, the culture was washed three times by centrifugation at 10,000 × g (Beckman; JA-21 or JA-20) for 20 min at 4°C in 125 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8. The last pellet was dissolved in the same buffer, and, instead of using a French press, it was frozen immediately in liquid N2 and thawed. This procedure was repeated 10 times. The suspension was centrifuged at 10,000 × g, and the supernatant was processed to obtain OMP by centrifugation at 100,000 × g (Beckman; TL-100 or SN-402) for 40 min at 4°C. Proteins in the pellet were extracted in Tris-HCl with 0.5% Sarkosyl for 30 min at 20°C and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for clarification and Sarkosyl elimination. The final pellet containing OMP was resuspended in Tris-HCl; the concentration of the OMP was measured by the Coomassie micromethod (Bio-Rad protein assay), and they were separated in aliquots and kept at −20°C.

Polyclonal antibody preparation.

New Zealand rabbits were injected subcutaneously with V. cholerae O1 Ogawa (52 μg), V. cholerae O1 Inaba (26 μg), V. cholerae O139 (22 μg), or V. alginolyticus (18 μg) OMP. For the first immunization OMP were mixed 1:1 with complete Freund's adjuvant (Microlab-Mexico); for the next two, performed with a 15-day interval, incomplete Freund's adjuvant (Microlab-Mexico) was used. Anti-Vibrio antibody production was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using heat-inactivated bacteria as the antigen. After the third injection antibodies were detected at high dilutions; thus sera were obtained and kept frozen in aliquots.

Standardization of a polyclonal antibody-based ELISA for bacterial antigen detection.

Bacteria were adjusted to 108 CFU/ml with a McFarland nephelometer, and serial dilutions up to 10 CFU/ml were prepared. Maxisorb plates (Nunc) were activated using UV exposure for 10 min as suggested by Boudet et al. (4); 100 μl of one dilution per well was adsorbed at 4°C overnight in carbonate buffer, and wells were washed and blocked with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.2–1% Tween–1% bovine serum albumin for 60 min. A similar volume of anti-Vibrio serum at serial dilutions from 1:100 to 1:102,400 was incubated for 1 h at 20°C; this was followed, after washing, by a 1:1,000 dilution of anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (as recommended by the manufacturer's protocol; Sigma), which was incubated in similar conditions. The enzymatic reaction was developed using H2O2 (0.012%) and orthophenylenediamine (400 μg/ml) in citrate buffer as the substrate.

Standardization of a bacterial antigen detection dot-ELISA with polyclonal antibodies.

The procedure used by Bosompem et al. (3) was followed with minor changes. Initially anti-OMP antiserum samples were evaluated; for this, serial bacterial dilutions, prepared in TSB as described above, were adsorbed to small disks (6 mm in diameter) of methanol-activated polyvinyl difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore), which were introduced into 24-microwell plates (Costar) to perform the reactions. Membranes were blocked using PBS–1% Tween–1% bovine serum albumin and washed three times with PBS, and 1 ml of an anti-OMP antiserum was added. The membranes were incubated, and after they were washed and incubated with the second antibody, color was developed with H2O2 (0.012%) and 3′,3-diaminobenzidine (400 μg/ml) in PBS. All incubations were performed for 30 min at 20°C.

For the detection of bacterial antigens in feces, defined concentrations of a dead bacterial strain were mixed with fecal samples from a healthy donor diluted in PBS (1:5) by soft stirring in an orbital shaker. The mixtures were immediately added to the PVDF disks, and the discs were processed as described above.

Evaluation of rectal swabs collected during surveillance activities.

Feces were recovered using rectal swabs during field activities, enriched in alkaline peptone water, pH 8 (8 h, 37°C), and separated in three aliquots. One was cultured in TCBS (18 to 24 h, 37°C); the other two were kept frozen (−20°C) until use. After observation of cultures and biochemical species confirmation, bacteria were incubated for a further 18 to 24 h at 37°C and the characteristic metabolism of V. cholerae was confirmed and the serogroup was identified (5a, 8, 9). Finally 18 samples were subjected to ELISA and dot-ELISA.

RESULTS

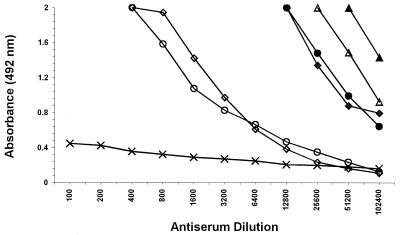

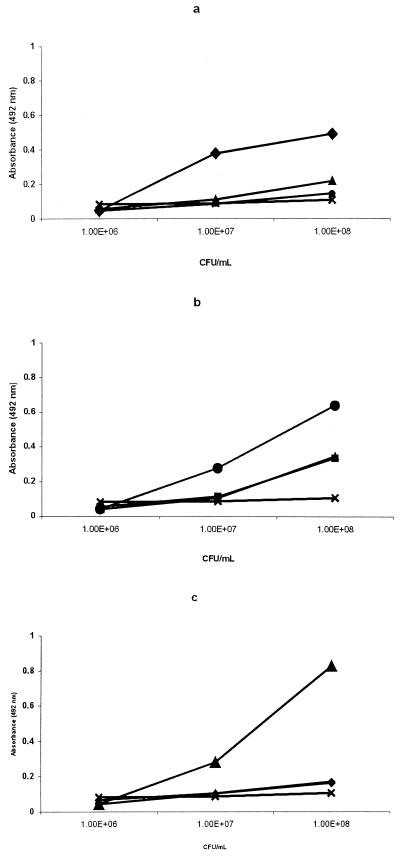

Polyclonal antisera raised against OMP antigens showed very high absorbance values in ELISA at high serum dilutions (between 1:12,800 and 1:102,400) with homologous antigens compared to antibodies prepared with Roshka antigens (between 1:400 and 1:3,200), routinely used in our institute. Sera raised against Vibrio OMP did not react with other enteric bacteria (listed in Materials and Methods; Fig. 1). Specificity was further demonstrated in ELISA by reactions of bacteria at different concentrations and the highest OMP antiserum dilution (Fig. 2). Ten to 100 million Ogawa and Inaba bacteria were detected by their homologous antiserum diluted 1:50,000, while O139 at the same level was detected with a 1:150,000 dilution of its specific antiserum. No reaction was found with other enteric bacteria (listed in Materials and Methods), and a very low reaction (except with the Inaba antiserum) with the heterologous antisera was found (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Reactivities of polyclonal antibodies prepared with OMP against bacterial antigens from V. cholerae O1 Ogawa (♦), V. cholerae O1 Inaba (●), V. cholerae O139 (▴), and V. alginolyticus (▵) and with Roshka antigens from V. cholerae O1 Ogawa (⋄) and V. cholerae O1 Inaba (○), as well as with the enteric bacteria listed in Materials and Methods (×).

FIG. 2.

The specificity of anti-Vibrio antibodies was defined using several CFU values for V. cholerae O1 Ogawa (♦), V. cholerae O1 Inaba (●), V. cholerae O139 (▴), and enteric bacteria listed in Materials and Methods (×). (a) Anti-V. cholerae O1 Ogawa (diluted 1:50,000); (b) anti-V. cholerae O1 Inaba (diluted 1:50,000); (c) anti-V. cholerae O139 (diluted 1:150,000).

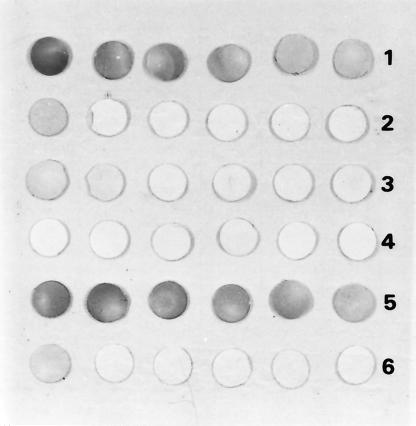

The reactivity in dot-ELISA of anti-OMP antisera was analyzed using several dilutions and 106 CFU of V. cholerae or enteric bacteria (listed in Materials and Methods)/ml. OMP antisera to Ogawa and O139 reacted against their specific adsorbed bacteria in all tested dilutions (1:500 to 1:16,000), but the anti-Inaba OMP reacted only in 1:500 and 1:1000 dilutions (Fig. 3). Eighteen randomly selected blind peptonated enriched samples from those kept frozen after surveillance activities were analyzed by ELISA and by dot-ELISA; 8 were positive and 10 were negative in both assays. These results agreed with microbiological and biochemical results, suggesting 100% sensitivity and specificity for the assays.

FIG. 3.

Evaluation of anti-V. cholerae antibodies by dot-ELISA. Bacteria were added to human fecal samples, adsorbed to PVDF membranes, and reacted with anti-V. cholerae O1 Ogawa (1 and 2), anti-V. cholerae Inaba (3 and 4), and anti-V. cholerae O139 (5 and 6). Bacteria (108 CFU/ml) used were V. cholerae O1 Ogawa (1), V. cholerae Inaba (3), V. cholerae O139 (5), and enteric bacteria (2, 4, and 6; listed in Materials and Methods). Antisera were diluted 1:500, 1:1,000, 1:2,000, 1:4,000, 1:8,000, and 1:16,000 from left to right.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the study described here was to obtain a sensitive and specific inmunodiagnostic assay for detection of V. cholerae that would avoid preenrichment and costly equipment so that it can be used for epidemiological surveillance and clinical diagnosis of cholera cases. For this, OMP from V. cholerae Inaba and Ogawa serotypes (18, 23) were obtained by employing a technique similar to that used for V. alginolyticus (18). OMP antigens induced a higher humoral immune response in rabbits than antibodies produced with the Roshka extracts, similar to previous findings (18). OMP antibodies were specific, as could be seen by the reactivity in ELISA with the different antisera produced. Some degree of cross-reaction between anti-Inaba serum and the Ogawa strain was seen; this could be related to the transformation of Inaba to Ogawa (5, 22). Also the anti-Inaba antiserum was less sensitive in the dot blot assay. Specificity of OMP has been shown previously (21), indicating that members of the Vibrionaceae family have different membrane antigens.

Whole bacteria were identified by ELISA and by dot-ELISA with OMP antisera using mixtures of known numbers of bacteria in human feces or frozen samples obtained from cases detected during surveillance activities. Concentrations of 106 and 108 CFU/ml were positive in dot-ELISA and ELISA, respectively. Probably the same sensitivity could be found with fresh human feces, but the feces obtained during epidemiological surveillance activities were, by routine, enriched in peptonated water, which increases the amount of bacteria. In natural infections bacterial concentrations of 106 CFU/ml are usually found in feces; thus the assays developed in this study suggest that direct detection of bacteria in fecal samples is feasible. This sensitivity could not be confirmed in field or clinical studies due to the lack of recent cases. Anti-V. cholerae O139 antibodies as well as those of other enteric bacteria (listed in Materials and Methods) had very low cross-reactivity against the O1 V. cholerae serogroups used, supporting the specificity of the assay. Furthermore the amount of specific antisera produced in this study is enough for 15,000 dot-ELISAs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Roshka antigens and polyclonal sera produced against them were kindly donated by MPH Celia González and QBP Altagracia Villanueva (InDRE, SSA).

REFERENCES

- 1.Albert M J, Islahm D, Nahar S, Qadri F, Falklind S, Weintraub A. Rapid detection of Vibrio cholerae O139 Bengal from stool specimens by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1633–1635. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1633-1635.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benenson A S, Islam M R, Greenough W B., III Rapid identification of Vibrio cholerae by darkfield microscopy. Bull W H O. 1964;30:827–831. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosompem K M, Ayi I, Anyan W K. A monoclonal antibody-based dipstick assay for diagnosis of urinary schistosomiasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:554–556. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boudet F J, Thèze J, Zovali M. UV treated polystyrene microtitre plates for use in an ELISA to measure antibodies against synthetic peptides. J Immunol Methods. 1991;142:73–82. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90294-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calia K E, Murtagh M, Ferraro M J, Calderwood S B. Comparison of Vibrio cholerae O139 with V. cholerae O1 Classical and El Tor biotypes. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1504–1506. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.4.1504-1506.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5a.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Laboratory methods for the diagnosis of Vibrio cholerae. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaicumpa W, Srimanote P, Sakolvaree Y, Kalampaheti T, Chongsa-Nguan M, Tapchaisri P, Eampokalap B, Moolasart P, Nair G B, Echeverria P. Rapid diagnosis of cholera caused by Vibrio cholerae O139. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3595–3600. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.12.3595-3600.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finkelstein R A, LaBrec E H. Rapid identification of cholera vibrios with fluorescent antibody. J Bacteriol. 1959;78:886–891. doi: 10.1128/jb.78.6.886-891.1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giono C S. Vibrio cholerae. In: Giono S, Escobar A, Valdespino J L, editors. Diagnóstico de laboratorio de infecciones gastrointestinales. Mexico City, México: Instituto de Diagnóstico y Referencia Epidemiológicos, Secretaría de Salud; 1994. pp. 309–350. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giono C S, Gutiérrez L, Hinojosa M. Manual de procedimientos para el aislamiento y caracterización de Vibrio cholerae O1: publicación técnica no. 10. Mexico City, México: Instituto de Diagnóstico y Referencia Epidemiológicos, Secretaría de Salud; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hasan J A K, Huq A, Tamplin M, Sieberlin R J, Colwell R R. A novel kit for rapid detection of Vibrio cholerae O1. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:249–252. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.1.249-252.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jesudason M V, Thangavelu C P, Lalitha M K. Rapid screening of fecal samples for Vibrio cholerae by a coagglutination technique. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;19:712–713. doi: 10.1128/jcm.19.5.712-713.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaper J B, Morris J G, Levine M M. Cholera. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:48–86. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kay B A, Bopp C A, Wells J G. Isolation and identification of Vibrio cholerae O1 from fecal specimens. In: Wachsmuth I K, Blake P A, Olsvik Ø, editors. Vibrio cholerae and cholera: molecular to global perspectives. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1994. pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lesmana M, Rockhill R C, Sutanti D, Sutomo A. A coagglutination test to detect Vibrio cholerae in feces alkaline peptone water cultures. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1982;13:337–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manning P A, Stroeher U H, Morona R. Molecular basis for O-antigen biosynthesis in Vibrio cholerae O1: Ogawa-Inaba switching. In: Wachsmuth I K, Blake P A, Olsvik Ø, editors. Vibrio cholerae and cholera: molecular to global perspectives. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1994. pp. 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moreira L A A. Cholera: molecular epidemiology, pathogenesis, immunology, treatment and prevention. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 1994;7:592–601. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris J G, Jr . the Cholera Laboratory Task Force. Vibrio cholerae O139 Bengal. In: Wachsmuth I K, Blake P A, Olsvik Ø, editors. Vibrio cholerae and cholera: molecular to global perspectives. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1994. pp. 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pruzzo C, Crippa A, Bertones S, Pane L, Carli A. Attachment of Vibrio alginolyticus to chitin mediated by chitin-binding proteins. Microbiology. 1996;142:2181–2186. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-8-2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahman M, Sack D, Mahmood S, Hossain A. Rapid diagnosis of cholera by coagglutination test using 4-h fecal enrichment cultures. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:2204–2206. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.11.2204-2206.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakasaki R. Bacteriology of Vibrio and related organisms. In: Dhiman B, Greenough III W B, editors. Cholera. New York, N.Y: Plenum Medical Book Company; 1992. pp. 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sengupta K D, Sengupta T K, Ghose A C. Major outer membrane proteins of Vibrio cholerae and their role in induction of protective immunity through inhibition of intestinal colonization. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4848–4855. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.11.4848-4855.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stoehr U H, Karageorgos L E, Morona R, Manning P A. Serotype conversion in Vibrio cholerae O1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2566–2570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tarsi R, Pruzzo C. Role of surface proteins in Vibrio cholerae attachment to chitin. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1348–1351. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.3.1348-1351.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]