Abstract

The gradual drying up of saltwater bodies creates habitats that are characterised by changing environmental conditions and might be available only for a subset of plants from the local flora. Using two terrestrial areas with different ages on the Caspian Coast as a chronosequence, we investigated factors including microtopography, ground water level and soil salinity that drive plant community succession after the retreat of the sea. Vegetation of the two key sites appearing after the retreat of the Caspian Sea about 365 and 1412 years ago were compared in terms of both evolutionary and ecological traits of plants. Both edaphic conditions and vegetation differed between the two sites with harsher edaphic conditions and more xerophytes on the elder site. Species that grew only in the ‘early’ site were dispersed across the phylogenetic tree, but their loss on the 'late' site was not random. Species that grew only on the 'late' site were phylogenetically clustered. On the level of microtopography, elevated spots were more densely populated in the ‘early’ site than lowered spots, but on the 'late' site the situation was opposite. The main edaphic factors that drive the difference in vegetation composition between the two sites are likely salinity and moisture. During environmental changes, different plant traits are important to survive and to appear in the community de novo. Microtopography is important for forming plant communities, and its role changes with time.

Subject terms: Biodiversity, Biogeography, Climate-change ecology, Community ecology, Grassland ecology, Restoration ecology

Introduction

The decreasing depth of waterbodies is observed mainly in coastal ecosystems of inland depressions located in semi-arid landscapes. In addition to the Aral1–4 and Caspian5–8 Seas, which are the largest drying waters, this phenomenon is observed in Lop Nur9–11, Chad, and smaller territories in Australia12, Africa13, and the Americas.

Being a closed water body dependent on the inflow of the Volga and the Ural rivers, the Caspian Sea had multiple stages of regressions and transgressions in the past when the sea coast was found at elevations from − 150 to + 50 m above the sea level14–16. The latest changes of the Caspian sea level lead to the formation of new dry land on its coasts17–19. New territories appear and are inhabited by plants. In the last 3000 years, the northern part of the Caspian Sea was under semiarid conditions20. Due to aridity, the salt accumulation was a typical process on the newly formed land. Salt-affected soils with high electrolyte content restrict the development of most plants except halophytes, which can survive. Much is still unknown about plant community succession caused by the reduction in groundwater level resulting from the drying up of the sea. As groundwater level continues to change, such a succession is likely to be highly dependent on changes in abiotic conditions that are not influenced by the community itself. In other words, it might be mostly allogenic. However, some mechanisms of autogenic (i.e. depending on community members) succession may also play a role. For example, large shrubs such as tamarisk might influence the growing conditions in their vicinity21, thus influencing the composition of community by facilitation or inhibition mechanisms22. Knowledge about the current changes and dynamics of vegetation might help to predict how the territory will look in the future and is critical for developing adaptation strategies to address the challenges posed by climate change and human activities on vulnerable and fragile semi-arid ecosystems23.

To understand the processes that drive changes in the structure of plant communities, a complex approach is needed that will consider edaphic factors, as well as ecological traits and the evolutionary history of plants that coexist or change each other during plant community succession24,25.

The microtopography with the amplitude of about 30 cm has a strong influence on water relocation and, hence, vegetation in semiarid landscapes of the Northern Caspian Lowland26–28. The microhighs receive 4 times less amount of water than microlows, which leads to formation of sparse halophyte vegetation on the tops and dense and diverse vegetation on the bottoms. This phenomenon is well studied at the developed old-aged landscapes at the altitudes of + 0 + 50 m a.s.l. However, the studies on the influence of microtopography on the patchiness of vegetation at the early stages (last centuries) after the retreat of the sea are not well represented in the literature.

In this work, two key sites of different ages were considered as proxy time points of evolution in the area after the Caspian Sea retreated. The two sites—‘early’ (Caspii-2 in our previous works) and ‘late’ (Caspii-1)—were freed from the sea about 293 and 1340 years ago, respectively29–31, and are located 1.6 km from each other. The names “early” and “late” reflect that the ‘early’ site is on earlier succession stage than the ‘late’ site. They were compared in terms of vegetation and edaphic factors to study temporal changes of the territory that newly appeared from under the sea in the semi-arid climate. We also compared the vegetation growing on different microtopographic positions (microhighs vs. microlows) both within each key site and between two key sites.

During this work, we tested the hypothesis that on highly saline soils (solonchaks) of the Caspian Lowland, elevations are a harsher environment for plants than depressions in both macro- (i.e. different regressive phases) and microscale (i.e. elements of microtopography—microhighs and microlows).

Materials and methods

Key area

The Early and Late key sites were of 30 × 45 and 50 × 50 m size, respectively (Table 1, Fig. S1). Plant communities of the studied key sites were considered as stages of plant colonization of the Caspian Sea coast released from water.

Table 1.

| Features | Early key site | Late key site |

|---|---|---|

| Coordinates |

N 44.5529 E 46.6769 |

N 44.5412 E 46.6642 |

| Altitude according to the Kronstadt tide gauge, m below sea level | − 25.8 | − 24.9 m |

| Drying age, years BP | 365 ± 13 | 1412 ± 36 |

| Radiocarbon age of the topsoil (0–10 cm) organic carbon, radiocarbon years cal BP (years before present with 1950 as the zero point of the timescale) | 293 ± 13 | 1340 ± 36 |

| Average diameter of the microhighs, m | 1–10 | 1–10 |

| Average height of microhighs, cm | 7–16 | 17–40 |

| Plant community | Tamarisk | Saltwort-suaeda |

| Total species number | 32 | 24 |

| Topsoil salinity (0–5 cm), dS/m | 11.9 ± 8.4 (N = 50) | 17.2 ± 14.2 (N = 40) |

| Subsoil salinity (30–50 cm), dS/m | 10.5 ± 1.9 (N = 50) | 13.5 ± 1.2 (N = 40) |

| Groundwater level, m | 2.8 | > 3.0 |

| Groundwater salinity, g/l | 44–48 | Not available |

As can be judged from the age of soil organic carbon, the short-term flooding in the beginning of the nineteenth century did not impact the ‘late’ key site significantly. Notably, the entire coastal zone of the northern part of the Caspian Sea was repeatedly subjected to flooding associated with storm surges, for example, in 1952 and 1995, the absolute water levels reached about − 24 m for several hours. However, it did not have an influence on the general development of the region’s landscape. At the ‘late’ key site, the lower western and the higher eastern parts were clearly distinguished. The ‘late’ site partially occupied the western slope of the coastal bar formed in the 1880s34.

The soils of the ‘late’ site were more saline than soils in the ‘early’ site29. At the ‘late’ site, a three-tier plant community consisting of a 0.5–1.0 m high Suaeda microphylla in the upper tier, a 0.2–0.5 m high Kalidium foliatum in the medium tier, and annual saltworts (Petrosimonia brachiata, Climacoptera crassa, Suaeda acuminata) with Frankenia hirsuta, Psylliostachys spersicicus and ephemeral plants in the lower herb’s tier occurred29. The vegetation of the ‘early’ site was a sparse degrading (deteriorating) community of a 1–1.5 m high tamarisk (Tamarix octandra mixed with some T. laxa) with annual saltworts (Petrosimonia brachiata, P. oppositifolia, Suaeda acuminata), Frankenia hirsute, and Puccinellia gigantea in the lower tier with some ephemeral plants29,30,35. In the lower tier, two microgroups were clearly distinguished. Open habitats were occupied by sparse stunted halophytic plants (Petrosimonia, Frankenia, Puccinellia). Under the crowns of the bushes, dense herb and grass microcommunities grew with a predominance of tall Puccinellia gigantea and a few Limonium caspium, L. scoparium, and Psylliostachys spicata, whereas saltworts and Frankenia were absent here.

Field work

In autumn and spring, soils were sampled from 1-m deep boreholes at depths of 0–5, 5–10, 10–20, 20–30, 30–50, 50–70, and 70–100 cm. At the ‘late’ site, 40 auger holes were drilled at a distance of 2 m from each other along a 50-m long transect (26 auger holes) and on different elements of microtopography (14 auger holes)—microhighs and microlows (Fig. S1). At the ‘early’ key site, in total, 58 auger holes were drilled according to a semi-regular grid with an interval of 1 to 5 m from each other.

In autumn, vegetation was described in 2 × 2 m plots throughout the key sites along 50-m long (at the ‘late’ key site, 350 descriptions) and 30-m long transects (at the ‘early’ key site, 345 descriptions) located at a distance of 2–4 m from each other. The descriptions included the number and size of the dominant shrubs, plant species, total projective cover of the herb tier, and the portion of bare ground and plant litter. As the main description of 2 × 2 m plots took place in autumn, only 11 perennial species were found in the ‘early’ site and 15 in the ‘late’ site. In addition, in the spring, the species composition of both sites was studied to compile a list of flora, including not only perennials but also annuals and ephemer(oid)s. The vast majority of species was identified in the field. The formal identification of the plant material used in this study was conducted by Yulia D. Nukhimovskaya and Nina Yu. Stepanova. Voucher specimens were deposited in a publicly available herbarium of the Tsytsyn Main Botanical Garden of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Table S3).

The Latin names of plant species were given according to the S.K. Cherepanov list36 based on the Takhtajan system37 during the field research and according to open-access continuously updated resources38,39 corresponded to the APG IV system40 to provide phylogenetic analysis. In subsequent work, autumn descriptions were used for analyses related to microtopography, species prevalence, and species co-occurrence. In phylogenetic analyses of the flora, full lists of flora present at the studied sites were used.

The microtopography was measured using dynamic GSP (DGPS) Stonex-9 Plus equipment which allows sub-centimetre accuracy of measurements. The DGSP readings were taken with one meter interval. Maps of microtopography were calculated in SAGA GIS using Ordinary Kriging method. The resulting dataset for the ‘early’ site consisted of 86 microhighs and 225 microlows (microhighs had a relative height of 7–16 cm above the microlows), and the resulting dataset for the ‘late’ site consisted of 151 microhighs and 130 microlows (microhighs had a relative height of 17–40 cm above the microlows).

Laboratory analysis and statistics

In soil samples, the electrical conductivity (EC) was measured in the lab with a 1:2.5 soil-to-water ratio using a Hanna Combo 98130 conductivity meter. In reference soil pits, located at typical microhighs and microlows, the moisture and soil bulk density were measured using the gravimetric method. All measures of EC as well as species composition of 2 × 2 plots are available as Supplementary Data.

Using published data, a list of 42 families from 22 orders of plants (Table S1) that grow on the Primorskaya lowland (in edaphic conditions typical for the key sites studied) was compiled (Tables S2, S3), as our key sites were located in the border between republics of Kalmykia and Dagestan (constituent entities of Russia; supplementary text 1).

Phylogenetic trees for Magnoliophyta species persistent in the ‘early’ or ‘late’ key sites and for families from the local flora were built based on a phylogenetic tree of Angiospermae from41. From either of the key sites, 27 of 35 species persisted in the phylogenetic tree of Angiospermae. Eight remaining species were added to the tree by adding their branches as basal polytomies within their genera or families with R scripts provided in41.

Taxonomic Distinctness Index based on presence-absence data was calculated as a mean pairwise taxonomic distance between species that were found in the community42.

Considering the two key sites as a proxy of time points along the chronosequence of the new terrestrial area, we investigated whether species that have been lost or acquired in the ‘late’ key site in compare with the ‘early’ site are randomly distributed, clustered or overdispersed across the evolutionary tree. The mean pairwise distance (MPD)—a measure that reflects the extent of phylogenetic clustering25—was calculated for species that were lost or acquired with time and compared with the null distributions for MPD as described in detail in our previous work43 and Supplementary text 2.

To determine whether species that had been lost in the ‘late' key site in comparison with the ‘early’ site preferably belonged to particular plant families, for each of 10 families of the ‘early’ site, the hypergeometric probability of losing the same or a greater number of species than were actually lost was counted under the null hypothesis that species were lost randomly.

To calculate the probability of four species acquired in the ‘late’ key site to belong to the same family Amaranthaceae by chance, the probability of each family to acquire a new species in the ‘late’ site was assumed to be proportional to its contribution to the species content of the ‘early’ site (fraction of the ‘early’ key site species belonging to this family). For Amaranthaceae, the hypergeometric probability of appearance of four new species or more was calculated under this null assumption.

Comparison of means (salinity [EC] and bare ground area) between microhighs and microlows at both key sites was performed with the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test.

All statistical analyses were performed with basic R language44. In a code for calculation of the taxonomic diversity index, “separate” function of “tidyr” package45 was used. Scripts that were written for this study are provided in Supplementary Folder 1 and on GitHub repository (https://github.com/GalkaKlink/CaspianSea) along with description of what they do.

Results

Distribution of Magnoliophyta families of the recent coastal lowland across evolutionary trees of local flora

The most abundant families in the dry steppes and deserts of the Caspian Sea region were Poaceae6,46,47 and Amaranthaceae. The last one includes the largest number of halophytes48–50. The ‘late’ site had 9 species of Amaranthaceae and 6 species of Poaceae, whereas the ‘early’ site had 6 species of Amaranthaceae and 10 species of Poaceae. Regarding the remaining eight families, the key sites had 1–3 (rarely 4) species belonging to them.

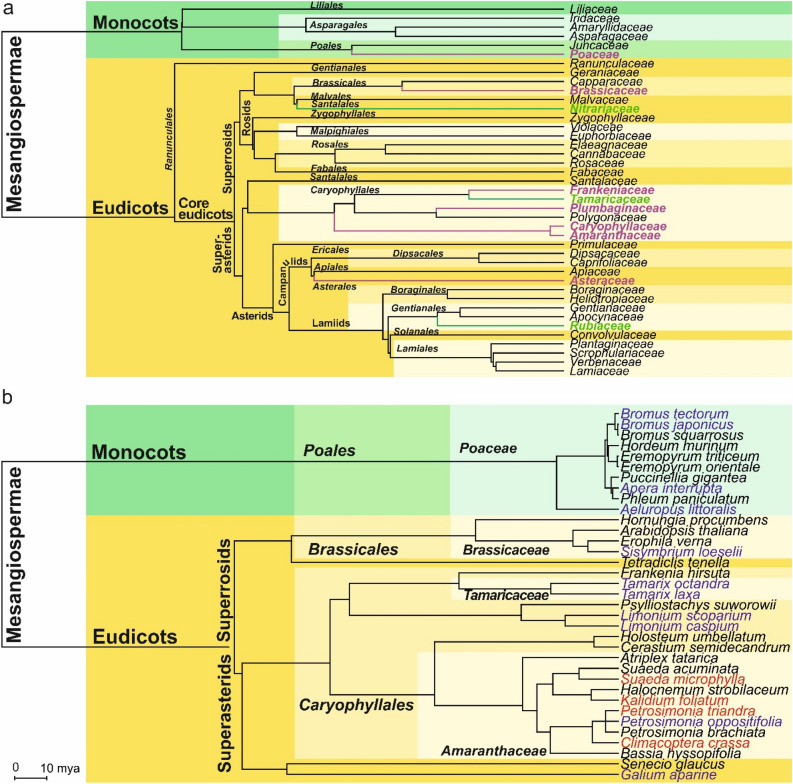

Ten families from the ‘early’ key site belonged to six orders and were not significantly clustered on the evolutionary tree (p-value for MPD = 0.14). Half of the ‘early’ key site families (5 of 10) were from the order Caryophyllales, making this order significantly overrepresented (hypergeometric left p-value = 0.0004) among the pioneer vegetation during the draining of the Caspian Sea (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of Magnoliophyta: (a) families growing in the western Caspian Sea cost in Dagestan and Kalmykia (purple—families that were found in both ‘early’ and ‘late’ sites, green—families that were found only in the ‘early’ site). (b) vegetation of the key sites (black—species that were found in both key sites, blue—species that were found only in the ‘early’ site, red—species that were found only in the ‘late’ site). Branch lengths are measured in millions of years.

Evolutionary analysis of species loss and gain

We have found 31 species in the Early site and 24 species in the Late site (Fig. 1b). The two key sites shared 20 species, which represented 65% and 83% of species found in the ’early’ and the ‘late’ sites, respectively. The flora of the two sites amounted to 35 species belonging to 10 families (Table S3). The number of common families was 8, which indicated a high degree of similarity of habitats in terms of family composition29.

We compared the diversity of two key sites by calculating the taxonomic distinctness index (TDI, see “Materials and methods”). Taxonomic diversity appeared to be similar for species that were found in the ‘early’ site, ‘late’ site, both sites and only in the ‘early’ site. However, it was twice smaller for species that were found only in the ‘late’ site, suggesting that this group consists of species that are closer related than species in other considered groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Species richness and taxonomic diversity of species that were found in the ‘early’ site and/or the ‘late’ site.

| Group | Number of species | TDI |

|---|---|---|

| Early site | 31 | 4.0 |

| Late site | 24 | 3.8 |

| Both sites | 20 | 4.0 |

| Only early site | 11 | 4.0 |

| Only late site | 4 | 2.0 |

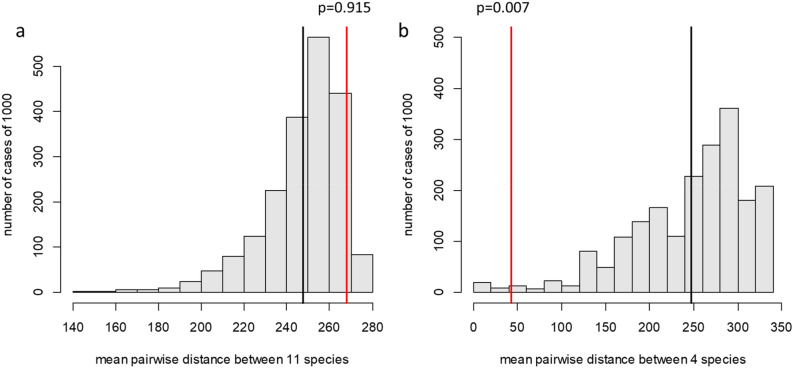

Among 31 species of the ‘early’ key site, 11 species were absent in the ‘late’ site. However, four new species appeared in the ‘late’ site, with 24 species in total (Table S3). Species lost in the ‘late’ site were distributed randomly across the phylogenetic tree (p-value for phylogenetic clustering = 0.915), whereas acquired species were highly clustered (p-value for phylogenetic clustering = 0.007, Fig. 1b, Fig. 2). No families lost less or more species than was expected by chance (Table S4). As for acquired species, all four belonged to one family (Amaranthaceae), which was unlikely to occur by chance (p = 0.00047, see “Materials and methods”).

Figure 2.

Null distributions for Mean Pairwise Distance (MPD) for 11 lost species (a) and 4 newly acquired species (b) in the ‘late’ site. The mean of each distribution is marked by a black line. MPD's of the lost (a) or newly acquired (b) species are marked by red lines. Above the red lines are the probabilities of occurrence of the observed or lower MPD for lost (a) or acquired (b) species in case of their random phylogenetic distribution.

Physical determinants of species loss and gain

The observed randomness of the phylogenetic distribution of species that were lost in the ‘late’ site could have occurred if the extinction was random. In such a case, the probability of a species to be lost would be proportional to its abundance in the ‘early’ key site. To test this, the abundance of each species in the ‘early’ site was estimated as a fraction of 2 × 2 plots, where this species was observed. Species that retained in the ‘late’ site were not more prevalent in the ‘early’ site than species that were lost in the ‘late’ site (one-sided Mann–Whitney test, p = 0.081), pointing that their extinction during succession was not random.

As salinity is considered the limiting factor for plant growth in the Caspian Sea coast, we tested whether differences in salinity between the two key sites may influence difference in their vegetation. Among several depth intervals (see “Materials and methods”), the percent of bare ground in 2 × 2 plots (both sites were considered together) showed the highest correlation with soil electroconductivity for a 30–50 cm layer (Spearman test, p = 0.0085, r = 0.3; Table S5). As root lengths of most species from the studied area fall within this interval (Table S3), it supports the importance of soil salinity for plant partitions in the studied area. For both microhighs and microlows, salinity was higher in the ‘late’ site than in the ‘early’ site for this soil layer (Table S6), suggesting that differences in salinity may be responsible, at least partially, for differences in vegetation coverage and composition between the two key sites.

To better understand the differences between 24 species that persisted in the 'late’ site and 11 species that persisted in the ‘early’ site but were absent in the ‘late’ site, two ecological characteristics of these species (an ability to live in a desert or being halophytic) were compared in binary form (yes/no) by Fisher’s exact test (Table S7). For spring descriptions, the ability to live in a desert (whether deserts are included in the species range, Table S3), a proxy of tolerance to water loss, was significantly overrepresented among species from the ‘late’ site (two-sided p = 0.001). Indeed, 83% of these species were desert plants in comparison with only 20% of species that were found only in the ‘early’ key site. Salt tolerance (whether the species is halophyte, Table S3) was not differentially represented (two-sided p = 1.00) among species found and lost in the ‘late’ key site, with 88% of persistent species and 90% of lost species. For autumn descriptions, desert species were no more overrepresented in the ‘late’ key site in comparison with plants from only the ‘early’ site, likely because the advantage of this feature becomes very high in both sites with the end of spring. Meanwhile, meadow plants became underrepresented in the ‘late’ site in autumn. Therefore, soil moisture and salinity might provide the differences in flora of the sites under consideration. In support of our assumption, three of four species that were met in the ‘late’ site but not in the ‘early’ site had a C4 type of photosynthesis (Table S3). C4-plants are known to be prevalent in arid environments and are believed to be more tolerant to increased soil salinity and water loss than plants with C3-type of photosynthesis51–53.

Along with abiotic factors, plant-plant interactions can also be responsible for differences in vegetation between the two sites. Large (> 1 m) tamarisk bushes seemed to influence the microtopographic structure and controlled the local microclimate around them. Tamarisk might serve as a nurse plant for some species in local patches. Therefore, some species could have been lost in the ‘late’ site due to tamarisk extinction. Among 10 species found in the ‘early’ key site in autumn, only Limonium scoparium occurred significantly more frequently in plots with large tamarisk bushes than in plots without large tamarisk (exact Fisher test, right-sided p-value = 0.003; Table S8), suggesting that tamarisk may serve as a nurse plant for this species and potentially for some ephemers, which is impossible to check with the available data.

Influence of microtopography on vegetation of the two key sites

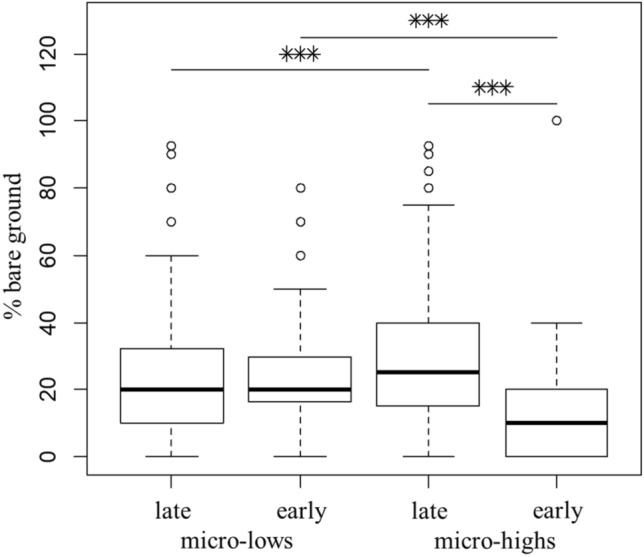

In the ‘early’ site (Fig. 3), the mean percentage of bare ground was greater (Mann–Whitney’s two-sided test, p = 0.136 × 10–6) for microlows (26%) than for microhighs (16%). However, in the ‘late’ site, the situation was reversed, and microlows had smaller uncovered area than microhighs (25% vs 31%, p = 0.0073). When comparing the two key sites, microlows had a similar percentage of bare ground in both key sites (p = 0.07), but microhighs had twice as large uncovered ground area in the ‘late’ site than in the ‘early’ key site (p = 0.114 × 10–6, Fig. 3). Therefore, microhighs of the 'early’ site were the most vegetated, whereas microhighs of the ‘late’ site were the least covered.

Figure 3.

Percentage of bare ground in microhighs and microlows of the key sites. Bold line is the median. Box borders represent the interquartile range (IQR) between first (Q1) and third (Q3) quartiles. Whiskers are Q1 – 1.5*IQR and Q3 + 1.5*IQR. ***, Mann–Whitney’s two-sided p-value < 0.001.

To evaluate the microtopography preferences of plants, for each species, its prevalence in the 2 × 2 m plots from microhighs and microlows was compared using Fisher’s exact test at each key site. For tamarisk in the ‘early’ key site, small, medium, and large individuals were analysed separately.

In the ‘early’ key site, Limonium scoparium was overrepresented in microhighs, whereas Petrosimonia brachiata and Suaeda acuminata were overrepresented in microlows (Table 3). Interestingly, large tamarisk specimens were overrepresented in microhighs, whereas small specimens were slightly overrepresented in microlows.

Table 3.

Differential prevalence of plant species between microhighs (“H”) and microlows (“L”).

| Species | ‘Late’ site | ‘Early’ site | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | L | p-value* | Preferred** | H | L | p-value* | Preferred** | |

| Atriplex tatarica | 0.007 | 0.076 | 0.002 | L | 0.047 | 0.071 | 0.613 | n.s. |

| Bassia hyssopifolia | 0.007 | 0.025 | 0.241 | n.s. | 0.000 | 0.008 | 1.000 | n.s. |

| Climacoptera crassa | 0.517 | 0.093 | 0.000 | H | – | – | – | – |

| Frankenia hirsuta | 0.026 | 0.490 | 0.000 | L | 0.581 | 0.669 | 0.150 | n.s. |

| Halocnemum strobilaceum | 0.026 | 0.053 | 0.279 | n.s. | 0.000 | 0.004 | 1.000 | n.s. |

| Kalidium foliatum | 0.351 | 0.612 | 0.000 | L | – | – | – | – |

| Limonium caspium | – | – | – | – | 0.081 | 0.031 | 0.066 | n.s. |

| Limonium scoparium | – | – | – | – | 0.174 | 0.047 | 0.001 | H |

| Petrosimonia brachiata | 0.901 | 0.622 | 0.000 | H | 0.419 | 0.674 | 0.000 | L |

| Petrosimonia oppositifolia | – | – | – | – | 0.174 | 0.229 | 0.361 | n.s. |

| Suaeda acuminata | 0.026 | 0.091 | 0.014 | L | 0.012 | 0.101 | 0.005 | L |

| Suaeda microphylla | 0.947 | 0.912 | 0.256 | n.s | – | – | – | – |

| Tamarisk big (> 1 m) | – | – | – | – | 0.744 | 0.238 | 0.000 | H |

| Tamarisk medium (0.5–1 m) | – | – | – | – | 0.372 | 0.459 | 0.167 | n.s. |

| Tamarisk small (< 0.5) | – | – | – | – | 0.314 | 0.454 | 0.023 | L |

| Tamarisk all | – | – | – | – | 0.860 | 0.833 | 0.609 | n.s. |

For each species, the fraction of plots at which it was found (i.e. the number of plots where this species was found divided by the total number of plots) is shown.

*p-value of Fisher’s exact test. Species witht p-value < 0.05 after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing are in bold. Species for which the p-value was significant only before the correction are underlined.

**Preferred site according to Fisher’s exact test; n.s.—test is insignificant. H—microhighs. L—microlows. Dash—plant species did not occur at the key site.

In the ‘late’ site, Climacoptera crassa and Petrosimonia brachiata were overrepresented in microhighs, and Atriplex tatarica, Frankenia hirsuta, and Suaeda acuminata were overrepresented in microlows (Table 3). Among shrubs, Kalidium foliatum was overrepresented in microlows.

The prevalence of species at microhighs and microlows was also compared between the two key sites (Table 4). Climacoptera crassa preferred microhighs of the ‘late’ site. For Petrosimonia brachiata, microhighs of the ‘late’ site were the most preferable and microhighs of the ‘early’ site were the least preferable areas. Frankenia hirsuta was highly prevalent in all 2 × 2 m plots, except for those at microhighs of the ‘late’ site. It grew on more than 50% of plots at microlows of the ‘early’ and ‘late’ site, as well as microhighs of the ‘early’ site, but less than on 3% of plots at microhighs of the ‘late’ site. Petrosimonia oppositifolia and Puccinellia gigantea preferred the ‘early’ site over the ‘late’ site, irrespective of microtopography.

Table 4.

Differential prevalence of plant species on microhighs and microlows between the key sites studied.

| Species | Microhighs | Microlows | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of plots with species | p-value | Preferred key site | % of plots with species | p-value | Preferred key site | |||

| Late site | Early site | Late site | Early site | |||||

| Atriplex tatarica | 0.7 | 4.7 | 0.060 | Early | 12 | 8.0 | 0.343 | Late |

| Atriplex triticeum | 0 | 0 | 1.000 | None | 0.8 | 0 | 0.366 | Late |

| Bassia hyssopifolia | 0.7 | 0 | 1.000 | Late | 3.8 | 0.9 | 0.105 | Late |

| Climacoptera crassa | 52 | 0 | 0.000 | Late | 12 | 0 | 0.000 | Late |

| Frankenia hirsuta | 2.6 | 58 | 0.000 | Early | 73 | 72 | 0.902 | Late |

| Halocnemum strobilaceum | 2.6 | 0 | 0.300 | Late | 7.7 | 0 | 0.000 | Late |

| Halocnemum strobilacium | 0 | 0 | 1.000 | None | 0 | 0.4 | 1.000 | Early |

| Kalidium foliatum | 35 | 0 | 0.000 | Late | 72 | 0 | 0.000 | Late |

| Limonium caspium | 0 | 8.1 | 0.001 | Early | 0 | 3.6 | 0.029 | Early |

| Limonium scoparium | 0 | 17 | 0.000 | Early | 0 | 5.3 | 0.005 | Early |

| Petrosimonia brachiata | 89 | 42 | 0.000 | Late | 68 | 72 | 0.397 | Early |

| Petrosimonia oppositifolia | 0 | 17 | 0.000 | Early | 0 | 25 | 0.000 | Early |

| Puccinellia gigantea | 0 | 84 | 0.000 | Early | 0 | 74 | 0.000 | Early |

| Suaeda acuminata | 2.6 | 1.2 | 0.656 | Late | 14 | 12 | 0.616 | Late |

| Suaeda mycrophylla | 88 | 0 | 0.000 | Late | 89 | 0 | 0.000 | Late |

| Tamarix sp. | 0 | 86 | 0.000 | Early | 0 | 87 | 0.000 | Early |

Species with Exact Fisher’s test p-value < 0.05 after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing are in bold.

Therefore, plant preferences depended complexly on microtopography, as well as area age. In the ‘early’ site, salinity depended on microtopography at a depth of 0–30 cm and was higher for microlows, whereas in the ‘late’ key site, microhighs and microlows differed in salinity only at a depth of 50–100 cm (Table S6). Given that 78% of species in the ‘early’ site and 88% of species at the ‘late’ site had a maximal root length of no more than 50 cm (Table S3), it suggests that the importance of soil salinity for differences in vegetation between plots is higher in the ‘early’ site than in the ‘late’ site.

Discussion

As the Caspian Sea gradually retreats, lands of different ages forming a chronosequence are available for research. In this paper, the system of two key sites that appeared from the Caspian Sea 1412 and 365 years ago were considered as a proxy of two time points to estimate how local plant communities appear and transform while the sea is drying. Such a technique of space-for-time substitution is frequently used in comparative studies of territories with different level of disturbance or different times since disturbance54. Although use of chronosequences is indispensable in case of long-term scales (as it is for our case), it may lead to wrong conclusions when some factors other than time have considerable influence on the differences between studied sites55. However, as our key sites are located less than in 2 km from each other, they experience similar influence of climatic factors and are available for colonization by the same plants. As the two key sites appeared from the sea with interval about 1000 years, their initial climatic conditions potentially might be different. However, the studied area has remained semi-arid for the 3000 years20. In this work, we were interested in transformation of young dried areas. Therefore, only two sites were considered. However, it will be interesting to consider the whole chronosequence covering 3000 years of the history of the Caspian Sea retreat in semi-arid conditions.

A decrease in species richness (number of species) as the sea retreats and the newly formed land becomes drier was previously recorded in studies of the Aral Sea region56. The previous work on the ‘early’ and ‘late’ key sites showed a decrease in species richness in the latter in comparison with the former. Meanwhile, the communities of the key sites were similar in terms of the number of biomorphotypes and annual herbs29. Here, using taxonomic diversity index, we found that despite differences in species richness, phylogenetic diversity was similar between the two key sites.

Our evolutionary analysis of species that were unique for either of the two key sites showed that species loss in the ‘late’ site in comparison with the ‘early’ site occurred irrespective of evolutionary relationships, whereas acquired species were phylogenetically clustered. Therefore, we suggest that different plant traits are important to survive and appear de novo in dynamic communities forming in the changing environment of the Caspian Sea coast. Traits that were important for staying in a community did not show a pronounced phylogenetic signal, and different plants may survive due to different combinations of traits. In contrast, the set of features important for coming into a community seems to be narrow and to have a strong phylogenetic signal on the evolutionary tree of the local flora. One may speculate that it is good to be a generalist to survive in changing conditions of the Caspian Sea coast, whereas it is necessary to be a specialist to break into the existing but stressed community. All species growing in the ‘late’ site but absent in the ‘early’ site belonged to the Amaranthaceae family, which is known to increase in proportion with the climate desertification in steppes57–60.

Our results suggest that microtopography has a noticeable impact on vegetation in both key sites. In the ‘early’ key site, the salinity of root-inhabited soil layers was lower for microhighs than for microlows, where the percentage of bare ground was greater contrary to our hypothesis. Therefore, for the ‘early’ key site, soil salinity was likely a determinant of better growing conditions at microhighs than at microlows. Additionally, big tamarisk bushes growing at microhighs of the ‘early’ site (and potentially forming them21) may serve as a nurse plant for some other plant species. The increase in the role of positive plant-plant interactions was previously shown for stressed environments61,62.

In the ‘late’ key site, microlows were better populated than microhighs. In the same time, the difference in soil salinity between microlows and microhighs was insignificant for root-inhabited layer, suggesting that factors other than salinity provide the difference in occupancy of microtopographic elements in this key site. Interestingly, Petrosimonia brachiata was significantly more abundant at microlows of the ‘early’ site and microhighs of the ‘late’ site, making it a potential indicator for highly stressed parts of the environment. Petrosimonia spp. were previously found to live in soils with salinity of 2 to 28 dS m–150,63.

As the ability to live in deserts appeared to be important for growth in the ‘late’ site, we suggest that soil moisture determines the composition of the plant community in the ‘late’ site. Disappearing of tamarisk in the ‘late’ key site may also suggest this, as tamarisk was shown to drop out of the community with the decrease in groundwater level in tugay forests of Middle Asia3. Additionally, the Chenopodioideae/Asteraceae ratio was 1.5 times higher for the ‘late’ site than for the ‘early’ site (9/1 vs 6/1, respectively), which indicates a more arid environment64,65. Therefore, species growing at the ‘late’ key site tended to be more tolerant to water loss than species growing at the ‘early’ site.

Conclusion

In the studied system, plant preferences were complexly correlated with microtopography and area age. Our hypothesis suggesting that for the studied area, the environment for plants is better in elevated areas than in lowlands was confirmed on macrolevel. However, on the level of microtopography it was confirmed only for elder site, whereas for the ‘early’ site our results suggest the opposite.

The phylogenetic distribution of species that were lost in the ‘late’ site in comparison with ‘early’ site was random, whereas species that appeared in the ‘late’ site but were absent in the ‘early’ site were highly clustered on a phylogenetic tree, suggesting that vulnerability to a changing environment depends on traits that do not show a phylogenetic signal, but the ability to appear in community de novo requires properties possessed by the Amaranthaceae family. Mosaic patches of vegetation had a pronounced correlation with microtopography. Edaphic conditions of microhighs and microlows changed with time, leading to changes in the spatial distribution of plants.

Our work demonstrates the importance of considering both evolutionary and ecological plant traits in studying plant community succession at the Caspian Sea coast.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to T.I. Chernov, M.P. Lebedeva and D.D. Sangadzhiev for their invaluable assistance during the field work.

Author contributions

G.K.: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software, visualization, writing—original draft preparation; writing—reviewing and editing; I.S.: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, funding acquisition, project administration, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, writing—reviewing and editing; Y.N.: formal identification of the plant material, data curation, field works, writing—reviewing and editing; Z.G.: Field works; N.S.: writing—reviewing and editing, formal identification of the plant material; M.K.: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, investigation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, field works, writing- reviewing and editing.

Funding

This study was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research, project No. 17-55-560006 “Soilscapes of marine plains in the Caspian region: primary differentiation and evolution” (field studies), Russian Science Foundation project No. 20-77-100010 “Pyrogenic fingerprints in subboreal deserts of Eurasia” (Formal analysis and Investigation) and Ministry of Education and Science of Russian Federation for supporting of the Herbarium of the Main Botanical Garden (MHA)—075-15-2021-678 (the plant identification).

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study is available in the Supplementary Data of this article. The data on one of the two key sites was published (Semenkov et al.30; 10.1016/j.dib.2020.105972). Voucher specimens are deposited in a publicly available herbarium of the Tsytsyn Main Botanical Garden of the Russian Academy of Sciences (the deposition number of all plant species collected: Tetradiclis tenella, MHA 0250435; Hymenolobus procumbens, MHA0269285; Halocnemum strobilaceum, MHA0269286; Suaeda microphylla, MHA0269287; Bassia hyssopifolia, MHA0269288; Kalidum foliatum, MHA0269289; Frankenia hirsuta, MHA0269290; Petrosimonia brachiata, MHA0269291; Petrosimonia oppositifolia, MHA0269292; Tamarix octandra, MHA0269293; Tamarix laxa, MHA0269294; Puccinellia gigantea, MHA0269295; Limonium scoparium, MHA0269296; Senecio noeanus, MHA0269297).

Code availability

All statistical procedures and data formatting was performed with basic functions. Perl and R scripts are available on GitHub https://github.com/GalkaKlink/CaspianSea.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-19863-5.

References

- 1.Shomurodov KF, Adilov BA. Current state of the flora of Vozrozhdeniya Island (Uzbekistan) Arid Ecosyst. 2019;9:97–103. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adilov B, et al. Transformation of vegetative cover on the Ustyurt Plateau of Central Asia as a consequence of the Aral Sea shrinkage. J. Arid Land. 2020;13:71–87. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuz’mina ZV, Treshkin SE. Soil salinization and dynamics of Tugai vegetation in the southeastern Caspian Sea region and in the Aral Sea coastal region. Eurasian Soil Sci. 1997;30:642–649. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuz’mina ZV, Shinkarenko SS, Solodovnikov DA. Main tendencies in the dynamics of floodplain ecosystems and landscapes of the lower reaches of the Syr Darya river under modern changing conditions. Arid Ecosyst. 2019;9:226–236. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimeyeva LA. Phytogeography of the northeastern coast of the Caspian Sea: Native flora and recent colonizations. J. Arid Land. 2013;5:439–451. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goryaev IA, Korablev AP. Halophytic vegetation in the west caspian lowland. Contemp. Probl. Ecol. 2020;13:514–521. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Novikova NM, Volkova NA, Ulanova SS, Chemidov MM. Change in vegetation on meliorated solonetcic soils of the Peri-Yergenian plain over 10 years (Republic of Kalmykia) Arid Ecosyst. 2020;10:194–202. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravanbakhsh M, Amini T, Hosseini SMN. Plant species diversity among ecological species groups in the Caspian Sea coastal sand dune; Case study: Guilan Province, North of Iran. Biodiversitas. 2015;16:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan S, Mu G, Xu Y, Zhao Z. Quarternary environmental evolution of the Lop Nur region, China. Dili Xuebao/Acta Geogr. Sin. 1998;53:332–340. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hao H, Ferguson DK, Chang H, Li CS. Vegetation and climate of the Lop Nur area, China, during the past 7 million years. Clim. Change. 2012;113:323–338. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li C, et al. Growth and sustainability of Suaeda salsa in the Lop Nur, China. J. Arid Land. 2018;10:429–440. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barrett G. Vegetation communities on the shores of a salt lake in semi-arid Western Australia. J. Arid Environ. 2006;67:77–89. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neffar S, Chenchouni H, Si Bachir A. Floristic composition and analysis of spontaneous vegetation of Sabkha Djendli in north-east Algeria. Plant Biosyst. 2016;150:396–403. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yanina TA. The Ponto-Caspian region: Environmental consequences of climate change during the Late Pleistocene. Quat. Int. 2014;345:88–99. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rychagov GI. Pleistocene History of the Caspian Sea. Moscow State University; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rychagov GI. The level mode of the Caspian Sea during the last 10000. Vestn. Mosk. Univ. Seriya 5 Geogr. 1993;2:38–49. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kroonenberg SB, et al. Solar-forced 2600 BP and Little Ice Age highstands of the Caspian Sea. Quat. Int. 2007;173–174:137–143. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kasimov NS, Lychagin MY, Kroonenberg SB. Geochemical indication of cyclic fluctuations of the caspian sea level. Vestn. Mosk. Univ. Seriya Geogr. 2011;2:72–77. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kroonenberg SB, Badyukova EN, Storms JEA, Ignatov EI, Kasimov NS. A full sea-level cycle in 65 years: Barrier dynamics along Caspian shores. Sediment. Geol. 2000;134:257–274. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bolikhovskaya N, Kasimov N. The evolution of climate and landscapes of the Lower Volga region during the Holocene. Geogr. Environ. Sustain. 2010;3:78–97. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Magomedov MM-R, Gasanov SM. Features of soil changes under crowns of the shrubberies tamarisk (Tamarix meyeri boiss, T. ramosissima zedeb) South Russ. Ecol. Dev. 2014;6:12–21. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Du N, et al. Facilitation or competition? The effects of the shrub species tamarix chinensis on herbaceous communities are dependent on the successional stage in an impacted coastal wetland of North China. Wetlands. 2017;37:899–911. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang L, Jiapaer G, Bao A, Guo H, Ndayisaba F. Vegetation dynamics and responses to climate change and human activities in Central Asia. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;599–600:967–980. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burke IC, et al. Plant–soil interactions in temperate grasslands. In: van Breemen N, et al., editors. Plant-Induced Soil Changes: Processes and Feedbacks. Springer; 1998. pp. 121–143. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Webb CO, Ackerly DD, McPeek MA, Donoghue MJ. Phylogenies and community ecology. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2002;33:475–505. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abaturov BD. Microdepression microrelief of Caspian Lowland and mechanisms of its formation. Arid. Ecosistemy. 2010;16:31–45. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sapanov MK. The results of soil water investigations in Djanybek stationary. Dokuchaev Soil Bull. 2016;83:22–40. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bolshakov AF, Bazykina GS. Natural biogeocenoses and the conditions of their existence. In: Rode AA, editor. Biogeocenotic Basis of the Reclamation of Semidesert in the Northern Caspain Lowland. Nauka; 1974. pp. 6–34. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Konyushkova MV, Nukhimovskaya YD, Gasanova ZU, Stepanova NY. The temporal change in variability of soil salinity and phytodiversity at the coastal plain of the Caspian Sea. Arid Ecosyst. 2020;10:312–321. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Semenkov I, Konyushkova M, Heidari A, Nukhimovskaya Y, Klink G. Data on the soilscape and vegetation properties at the key site in the NW Caspian Sea coast, Russia. Data Br. 2020;31:105972. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2020.105972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Konyushkova MV, et al. Spatial and seasonal salt translocation in the young soils at the coastal plains of the Caspian Sea. Quat. Int. 2021;590:15–25. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Semenkov I, Konyushkova M, Heidari A, Nikolaev E. Chemical differentiation of recent fine-textured soils on the Caspian Sea coast: A case study in Golestan (Iran) and Dagestan (Russia) Quat. Int. 2021;590:48–55. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haghani S, et al. An early ‘Little Ice Age’ brackish water invasion along the south coast of the Caspian Sea (sediment of Langarud wetland) and its wider impacts on environment and people. Holocene. 2016;26:3–16. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panin GN, Mamedov RM, Mitrofanov IV. Present State of the Caspian Sea. Nauka; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Konyushkova MV, et al. The spatial differentiation of soil salinity at the young saline coastal plain of the Caspian region. Dokuchaev Soil Bull. 2018;95:41–57. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cherepanov SK. Vascular Plants of Russia and Adjacent States (Within the Former USSR) Cambridge University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takhtajan A. Flowering Plants. Springer Science+Business Media B.V; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Govaerts R, Nic Lughadha E, Black N, Turner R, Paton A. The World Checklist of Vascular Plants, a continuously updated resource for exploring global plant diversity. Sci. Data. 2021;8:215. doi: 10.1038/s41597-021-00997-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.POWO. Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, 2022).

- 40.Chase MW, et al. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2016;181:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qian H, Jin Y. An updated megaphylogeny of plants, a tool for generating plant phylogenies and an analysis of phylogenetic community structure. J. Plant Ecol. 2016;9:233–239. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clarke KR, Warwick RM. A taxonomic distinctness index and its statistical properties. J. Appl. Ecol. 1998;35:523–531. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Semenkov IN, et al. The variability of soils and vegetation of hydrothermal fields in the Valley of Geysers at Kamchatka Peninsula. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:11077. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-90712-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020).

- 45.Wickham, H. & Henry, L. tidyr: Tidy Messy Data. R Packag. version 1.0.0 (2019).

- 46.Goryaev IA. Regularities of distribution of halophytic vegetation on the Caspian Lowland. Bot. Zhurnal. 2019;104:1072–1089. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soltanmuradova ZI, Teimurov AA. Taxonomic structure of the flora of the Primorskaya Lowland of the Republic of Dagestan. South Russ. Ecol. Dev. 2010;3:38. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zörb C, Sümer A, Sungur A, Flowers TJ, Özcan H. Ranking of 11 coastal halophytes from salt marshes in northwest Turkey according their salt tolerance. Turk. J. Botany. 2013;37:1125–1133. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao Y, Yu H, Zhang T, Guo J. Mycorrhizal colonization of chenopods and its influencing factors in different saline habitats, China. J. Arid Land. 2017;9:143–152. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Podar D, et al. Morphological, physiological and biochemical aspects of salt tolerance of halophyte Petrosimonia triandra grown in natural habitat. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants. 2019;25:1335–1347. doi: 10.1007/s12298-019-00697-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nayyar H, Gupta D. Differential sensitivity of C3 and C4 plants to water deficit stress: Association with oxidative stress and antioxidants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2006;58:106–113. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Way DA, Katul GG, Manzoni S, Vico G. Increasing water use efficiency along the C3 to C4 evolutionary pathway: A stomatal optimization perspective. J. Exp. Bot. 2014;65:3683–3693. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Atia A, et al. Ecophysiological aspects in 105 plants species of saline and arid environments in Tunisia. J. Arid Land. 2014;6:762–770. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pickett, S. T. A. Space-for-time substitution as an alternative to long-term studies. In Long-Term Studies in Ecology 110–135 (1989) 10.1007/978-1-4615-7358-6_5.

- 55.Walker LR, Wardle DA, Bardgett RD, Clarkson BD. The use of chronosequences in studies of ecological succession and soil development. J. Ecol. 2010;98:725–736. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dimeeva, L. A. Dynamics of vegetation in deserts of Aral and Caspian regions. (2011).

- 57.Yu K, et al. Late quaternary environments in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia: Vegetation, hydrological, and palaeoclimate evolution. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2019;514:77–91. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cao X, Tian F, Dallmeyer A, Herzschuh U. Northern Hemisphere biome changes (>30°N) since 40 cal ka BP and their driving factors inferred from model-data comparisons. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2019;220:291–309. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang D, et al. Response of vegetation to Holocene evolution of westerlies in the Asian Central Arid Zone. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2020;229:106138. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lu KQ, et al. A new approach to interpret vegetation and ecosystem changes through time by establishing a correlation between surface pollen and vegetation types in the eastern central Asian desert. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2020;551:109762. [Google Scholar]

- 61.He Q, Bertness MD, Altieri AH. Global shifts towards positive species interactions with increasing environmental stress. Ecol. Lett. 2013;16:695–706. doi: 10.1111/ele.12080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ziffer-Berger J, Weisberg PJ, Cablk ME, Osem Y. Spatial patterns provide support for the stress-gradient hypothesis over a range-wide aridity gradient. J. Arid Environ. 2014;102:27–33. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vinogradov BV. Plant Indicators and Their Use in the Study of Natural Resources. Visshaya shkola; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Luo C, et al. Characteristics of the modern pollen distribution and their relationship to vegetation in the Xinjiang region, northwestern China. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 2009;153:282–295. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao Y, Herzschuh U. Modern pollen representation of source vegetation in the Qaidam Basin and surrounding mountains, north-eastern Tibetan Plateau. Veg. Hist. Archaeobot. 2009;18:245–260. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study is available in the Supplementary Data of this article. The data on one of the two key sites was published (Semenkov et al.30; 10.1016/j.dib.2020.105972). Voucher specimens are deposited in a publicly available herbarium of the Tsytsyn Main Botanical Garden of the Russian Academy of Sciences (the deposition number of all plant species collected: Tetradiclis tenella, MHA 0250435; Hymenolobus procumbens, MHA0269285; Halocnemum strobilaceum, MHA0269286; Suaeda microphylla, MHA0269287; Bassia hyssopifolia, MHA0269288; Kalidum foliatum, MHA0269289; Frankenia hirsuta, MHA0269290; Petrosimonia brachiata, MHA0269291; Petrosimonia oppositifolia, MHA0269292; Tamarix octandra, MHA0269293; Tamarix laxa, MHA0269294; Puccinellia gigantea, MHA0269295; Limonium scoparium, MHA0269296; Senecio noeanus, MHA0269297).

All statistical procedures and data formatting was performed with basic functions. Perl and R scripts are available on GitHub https://github.com/GalkaKlink/CaspianSea.