This cross-sectional study characterizes clinicopathologic factors associated with tumor tissue–modified human papillomavirus DNA.

Key Points

Question

What accounts for variations in the detection and level of circulating tumor tissue–modified viral (TTMV) human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA in patients with HPV-positive oropharynx squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC)?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 110 patients with HPV-positive OPSCC for whom pretreatment circulating TTMV HPV DNA was assayed, multiple measures of nodal metastatic disease burden were strongly associated with circulating TTMV HPV DNA prevalence and score.

Meaning

Circulating TTMV HPV DNA was associated with nodal disease burden in HPV-positive OPSCC, warranting further study of the mechanisms underlying this association and its implications for biomarker-based HPV-positive OPSCC diagnosis and surveillance.

Abstract

Importance

Circulating tumor tissue–modified viral (TTMV) human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA is a dynamic, clinically relevant biomarker for HPV-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Reasons for its wide pretreatment interpatient variability are not well understood.

Objective

To characterize clinicopathologic factors associated with TTMV HPV DNA.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study included patients evaluated for HPV-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts, between December 2019 and January 2022 and who were undergoing curative-intent treatment.

Exposures

Clinicopathologic characteristics including demographic variables, tumor and nodal staging, HPV genotype, and imaging findings.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Pretreatment circulating TTMV HPV DNA from 5 genotypes (16, 18, 31, 33, and 35) assessed using a commercially available digital droplet polymerase chain reaction–based assay, considered as either detectable/undetectable or a continuous score (fragments/mL).

Results

Among 110 included patients, 96 were men (87%) and 104 were White (95%), with a mean (SD) age of 62.2 (9.4) years. Circulating TTMV HPV DNA was detected in 98 patients (89%), with a median (IQR) score of 315 (47-2686) fragments/mL (range, 0-60 061 fragments/mL). Most detectable TTMV HPV DNA was genotype 16 (n = 86 [88%]), while 12 patients (12%) harbored other genotypes. Circulating TTMV HPV DNA detection was most strongly associated with clinical N stage. Although few patients had clinical stage N0 disease, only 4 of these 11 patients (36%) had detectable DNA compared with 94 of 99 patients (95%) with clinical stage N1 to N3 disease (proportion difference, 59%; 95% CI, 30%-87%). Among patients with undetectable TTMV HPV DNA, more than half (7 of 12 [58%]) had clinical stage N0 disease. The TTMV HPV DNA prevalence and score increased with progressively higher clinical nodal stage, diameter of largest lymph node, and higher nodal maximum standardized uptake value on positron emission tomography/computed tomography. In multivariable analysis, clinical nodal stage and nodal maximum standardized uptake value were each strongly associated with TTMV HPV DNA score. Among 27 surgically treated patients, more patients with than without lymphovascular invasion had detectable TTMV HPV DNA (12 of 12 [100%] vs 9 of 15 [60%]).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cross-sectional study, circulating TTMV HPV DNA was statistically significantly associated with nodal disease at HPV-positive OPSCC diagnosis. The few patients with undetectable levels had predominantly clinical stage N0 disease, suggesting assay sensitivity for diagnostic purposes may be lower among patients without cervical lymphadenopathy. Mechanisms underlying this association, and the use of this biomarker for surveillance of patients with undetectable baseline values, warrant further investigation.

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive oropharynx squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) is increasingly common in the US and other developed countries, with an incidence that is projected to continue rising for at least the next several decades.1,2 Plasma circulating tumor HPV DNA (ctHPVDNA) has emerged as a dynamic and clinically relevant biomarker for HPV-positive OPSCC. It has high sensitivity and specificity for disease detection3,4,5 with excellent predictive value for recurrence in the posttreatment setting6,7,8 and has been detected several years prior to diagnosis.9

Plasma ctHPVDNA level demonstrates wide interpatient variability, and despite its excellent sensitivity, there remains a small subset of patients with HPV-positive OPSCCs for whom it is not detectable (2%-30%).3,4,10,11,12 Reasons for this variability have not been well characterized but are critical to understand as this biomarker is increasingly used in both the research setting and in the clinic.

In this cross-sectional study, we analyzed plasma from a large cohort of patients with HPV-positive OPSCC using a commercially available digital droplet polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based assay that is designed to specifically assess tumor tissue–derived HPV DNA in plasma, yielding a normalized circulating tumor tissue–modified viral (TTMV) HPV DNA score. The objective of this study was to characterize clinical, pathologic, and imaging features associated with TTMV HPV DNA level and detectability among individuals with HPV-positive OPSCC to improve the understanding of this emerging biomarker with broad implications for screening, diagnosis, management, and surveillance.

Methods

Study Design and Population

This cross-sectional study included eligible patients with incident or recurrent HPV-associated OPSCCs without distant metastases evaluated at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, Massachusetts, between December 2019 and January 2022 who underwent circulating TTMV HPV DNA testing prior to treatment initiation. Testing was completed either as part of a separate institutional review board–approved protocol, for which written informed consent was provided, or during the course of routine clinical care, for which waiver of informed consent was obtained. Tumors were considered HPV-positive OPSCCs if they were determined p16 positive through immunohistochemistry results and/or high-risk HPV positive by RNA in situ hybridization (ISH) during routine clinical care. This study was approved by the Mass General Brigham Institutional Review Board and followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines.

Digital droplet PCR analysis of circulating TTMV HPV DNA from 5 HPV types (16, 18, 31, 33, and 35) was performed using the commercially available NavDx assay by Naveris, an independent, College of American Pathologists–accredited, Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified laboratory as previously described.4,8,9 NavDx is designed to specifically measure tumor-derived HPV DNA by algorithmic analysis of digital droplet PCR data leveraging tumor-specific fragmentation patterns.4,8,9 NavDx first tests for HPV-16, only assaying the other types if the sample is negative for HPV-16.9 Results are reported as normalized TTMV HPV DNA fragments per milliliter of plasma (frag/mL) and categorized as positive (>7 HPV-16 or >12 non-HPV-16 frag/mL), negative (<5 frag/mL), or indeterminate (5-7 HPV-16 or 5-12 HPV-18/31/33/35 frag/mL). For this analysis, indeterminate values were assigned a score equal to the median of the indeterminate range (6 frag/mL for HPV-16 and 8.5 frag/mL for non-HPV-16) and considered detectable. NavDx results are typically returned to the clinical team within 1 to 2 weeks.

Clinicopathologic characteristics and neutrophil:lymphocyte ratio (NLR) most proximal to the time of circulating TTMV HPV DNA testing before treatment initiation were obtained via electronic medical record abstraction. Race was self-reported by patients in medical records and was collected because of known differences in the epidemiology of HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer by race. Owing to the small sample size, non-White patients were categorized together as other race, inclusive of American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, more than 1 race, and unknown race. To capture true disease burden at the time of plasma testing, and considering the short half-life of ctHPVDNA,13 clinical and pathologic staging (American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual, 8th edition) were adjusted to reflect disease burden at time of blood collection in cases of excisional diagnostic procedures (eg, tonsillectomy or excisional lymph node biopsy). For example, patients who underwent diagnostic tonsillectomy prior to blood collection with no apparent residual tonsil disease were assigned clinical stage T0. Surgical treatment was considered oncologic primary tumor resection with cervical lymphadenectomy. Clinical extranodal extension (ENE) was recorded as designated by the clinical team at consultation (eg, in the presence of a fixed neck mass or obvious ENE on imaging). Pretreatment computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET)/CT were reviewed by a radiologist with expertise in head and neck cancer imaging (N.T.). Cervical lymph nodes were evaluated on imaging for 6 radiologic features considered suggestive for ENE: (1) perinodal fat stranding, (2) loss of perinodal fat plane, (3) lobular contours, (4) irregular nodal margin, (5) central nodal necrosis, and (6) nodal conglomerate.14,15,16,17

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported including No. (%), mean (SD), and median (IQR). Differences in proportions and medians were reported with 95% CIs when comparing 2 groups. Kendall τ18 with 95% CIs were used to estimate association strengths when comparing proportions among more than 2 groups (considered very weak for Kendall τ less than ±0.10, weak for ±0.10-0.19, moderate for ±0.20-0.29, and strong for ±0.30 or greater). To estimate effect size, η2 with 95% CIs were used19 to estimated effect size when comparing medians among more than 2 groups (small for η2 = 0.01, medium for η2 = 0.06, and large for η2 = 0.14). Regression analysis was performed to evaluate factors associated with TTMV HPV DNA score as a continuous variable. Because of the right-skewed nature of TTMV HPV DNA score and inclusion of zeros, a Box-Cox transformation was applied to TTMV as TTMV(λ) = log(TTMV + λ), λ = 2. The transformed outcome failed the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality; thus, a generalized linear model with a γ distribution with log link function was used, which relaxes the assumption that the residuals be normally distributed and homoscedastic. Unadjusted and adjusted estimates of the exponent of the parameter estimates (Exp[β]) with 95% CIs were reported. Logistic regression analysis was also performed to evaluate factors associated with TTMV HPV DNA detection, presented with adjusted odds ratios (AORs) reported with 95% CIs. A 2-sided P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Stata, version 14.2 (StataCorp), and R, version 4.1.0 (R Foundation).

Results

Study Population

The study population comprised 110 patients (Table 1) with characteristics typical of patients with HPV-positive OPSCCs. Most patients were men (n = 96 [87%]) and White (n = 104 [95%]) with a mean (SD) age of 62.2 (9.4) years. All but 2 patients had incident disease; 1 patient was treated 7 years prior for an HPV-positive cervical squamous cell carcinoma of unknown primary, and another had local recurrence 15 months after initial treatment. One hundred and eight patients (98%) had p16-positive tumors on clinical testing, and the remaining 2 (2%) had tumors that were not tested for p16 but were positive by ISH for HPV-16 (n = 1) or unspecified high-risk HPV (n = 1). There were 13 patients (12%) with p16-positive tumors but without HPV ISH results available clinically.

Table 1. Clinicopathologic and Radiographic Characteristics Compared With Circulating TTMV HPV DNA Detectability and Score.

| Characteristic | No. in each category (% of total) | No. in each category with detectable TTMV HPV DNA (% of category) | Effect sizea | TTMV HPV DNA score, median (IQR), frag/mLb | Effect sizec | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion difference (95% CI) | Kendall τ (95% CI) | Difference in medians (95% CI) | η2 (95% CI) | ||||

| Total | 110 | 98 (89) | NA | NA | 315 (47 to 2686) | NA | NA |

| Clinicopathologic characteristics | |||||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 14 (13) | 12 (86) | 0.04 (−0.16 to 0.23) | NA | 75 (9 to 193) | 305 (143 to 814) | NA |

| Male | 96 (87) | 86 (90) | 380 (65 to 2829) | ||||

| Age, y | |||||||

| <50 | 11 (10) | 11 (100) | NA | 0.008 (−0.113 to 0.031) | 5404 (110 to 10 292) | NA | 0.04 (0.00 to 0.10) |

| 50-59 | 29 (26) | 25 (86) | 117 (19 to 1282) | ||||

| 60-69 | 48 (44) | 44 (92) | 284 (84 to 2194) | ||||

| ≥70 | 22 (20) | 18 (82) | 850 (19 to 71 77) | ||||

| Raced | |||||||

| White | 104 (95) | 93 (89) | 0.061 (−0.243 to 0.365) | NA | 315 (45 to 2688) | 199 (−476 to 3295) | NA |

| Other | 6 (5) | 5 (83) | 434 (82 to 1946) | ||||

| Smoking status | |||||||

| Never | 51 (46) | 45 (88) | NA | 0.001 (−0.019 to 0.022) | 281 (67 to 4058) | NA | 0.10 (0.02 to 0.19) |

| Former | 52 (47) | 47 (90) | 314 (28 to 1895) | ||||

| Current | 7 (6) | 6 (86) | 1946 (3 to 29 382) | ||||

| Tumor site | |||||||

| Tonsil | 47 (43) | 42 (89) | NA | 0.003 (−0.021 to 0.026) | 171 (31 to 3895) | NA | 0.09 (0.00 to 0.27) |

| Tongue base | 53 (48) | 46 (87) | 354 (109 to 1971) | ||||

| Overlapping | 4 (4) | 4 (100) | 462 (115 to 1213) | ||||

| Unknown primarye | 6 (5) | 6 (100) | 2046 (1253 to 14 458) | ||||

| Clinical T stagef | |||||||

| T0 | 10 (9) | 9 (90) | NA | 0.018 (−0.006 to 0.042) | 668 (13 to 3690) | NA | 0.01 (0.00 to 0.03) |

| T1 | 37 (34) | 29 (78) | 193 (31 to 1819) | ||||

| T2 | 38 (35) | 36 (95) | 477 (75 to 4210) | ||||

| T3 | 10 (9) | 10 (100) | 385 (171 to 1946) | ||||

| T4 | 15 (14) | 14 (93) | 354 (109 to 2968) | ||||

| Clinical N stagef | |||||||

| N0 | 11 (10) | 4 (36) | NA | 0.032 (0.008 to 0.057) | 0 (0 to 21) | NA | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.06) |

| N1 | 69 (63) | 65 (94) | 344 (72 to 2410) | ||||

| N2 | 28 (25) | 27 (96) | 804 (230 to 3566) | ||||

| N3 | 2 (2) | 2 (100) | 3339 (22 to 6656) | ||||

| HPV genotype | |||||||

| Non–HPV-16 | 12 (12) | NA | NA | NA | 152 (40 to 313) | 562 (111 to 1591) | NA |

| HPV-16 | 86 (88) | NA | 720 (116 to 4451) | ||||

| Clinical ENE | |||||||

| No | 99 (90) | 88 (89) | 0.02 (−0.16 to 0.20) | NA | 281 (47 to 2407) | 1157 (335 to 18091) | NA |

| Yes | 11 (1) | 10 (91) | 1438 (19 to 18 339) | ||||

| Radiographic characteristics | |||||||

| Computed tomography | |||||||

| Primary tumor diameter, cm | |||||||

| <2 | 50 (52) | 43 (86) | NA | 0.016 (−0.007 to 0.040) | 315 (31 to 4058) | NA | 0.03 (0.00 to 0.07) |

| 2-3.9 | 41 (43) | 40 (98) | 545 (95 to 1946) | ||||

| ≥4 | 5 (5) | 5 (100) | 389 (428 to 2968) | ||||

| Largest node diameter, cm | |||||||

| <2 | 24 (25) | 17 (71) | NA | 0.031 (0.008 to 0.054) | 45 (0 to 267) | NA | 0.07 (0.00 to 0.14) |

| 2-2.9 | 25 (26) | 24 (96) | 935 (109 to 4451) | ||||

| 3-3.9 | 26 (27) | 26 (100) | 739 (205 to 5986) | ||||

| ≥4 | 21 (22) | 21 (100) | 1402 (254 to 5404) | ||||

| No. of nodal ENE features | |||||||

| 0-1 | 19 (20) | 15 (79) | NA | 0.026 (0.004 to 0.047) | 58 (13 to 386) | NA | 0.03 (0.00 to 0.09) |

| 2-3 | 27 (28) | 23 (85) | 248 (68 to 2410) | ||||

| >3 | 50 (52) | 50 (100) | 823 (162 to 5404) | ||||

| Positron emission tomography | |||||||

| Primary tumor SUVmax | |||||||

| <5 | 16 (15) | 13 (81) | NA | 0.023 (0.002 to 0.045) | 770 (17 to 2550) | NA | 0.05 (0.00 to 0.11) |

| 5-10 | 27 (25) | 22 (81) | 162 (9 to 3895) | ||||

| 10-15 | 31 (29) | 27 (87) | 209 (43 to 764) | ||||

| >15 | 34 (31) | 34 (100) | 838 (205 to 7177) | ||||

| Nodal SUVmax | |||||||

| <5 | 21 (19) | 13 (62) | NA | 0.041 (0.019 to 0.063) | 21 (0 to 95) | NA | 0.06 (0.00 to 0.13) |

| 5-10 | 27 (25) | 23 (85) | 569 (58 to 2968) | ||||

| 10-15 | 38 (35) | 38 (100) | 315 (93 to 2686) | ||||

| >15 | 22 (20) | 22 (100) | 1765 (8 to 6656) | ||||

Abbreviations: ENE, extranodal extension; frag/mL, fragments per milliliter; HPV, human papillomavirus; NA, not applicable; SUVmax, maximum standardized uptake value; TTMV, tumor tissue–modified viral.

Effect size metrics for comparisons of the proportion of patients with detectable TTMV HPV DNA include proportion difference for characteristics with 2 categories and Kendall τ for characteristics with more than 2 categories.

TTMV scores are rounded to the nearest integer value.

Effect size metrics for comparisons of median TTMV HPV DNA scores include difference in medians for characteristics with 2 categories and η2 for characteristics with more than 2 categories.

Race was self-reported by patients in their electronic medical records. Other race includes individuals who were Asian (n = 1), Black (n = 3), more than 1 race (n = 1), or unknown (n = 1).

There are fewer unknown primary than T0 tumors because patients undergoing excisional primary tumor biopsies (n = 4, all tonsillectomies) were assigned T0 stage to reflect tumor burden at the time of plasma collection.

Stages are based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual, 8th edition, at time of plasma collection (eg, adjusted for excisional diagnostic procedures).

Circulating TTMV HPV DNA Detection

Circulating TTMV HPV DNA was reported as positive in 96 patients (87%), indeterminate in 2 (2%; considered “detectable” for this analysis), and negative in 12 (11%). The TTMV HPV DNA genotype was most commonly HPV-16 (n = 86 [88%]), followed by HPV-33 (n = 8 [8%]), HPV-35 (n = 2 [2%]), HPV-31 (n = 1 [1%]), and HPV-18 (n = 1 [1%]). Among the 12 patients with undetectable circulating TTMV HPV DNA, all tumors were p16 positive and 11 harbored HPV types 16, 18, or 33 by RNA ISH or tissue TTMV HPV DNA testing (eTable 1 in the Supplement). The remaining patient had no tissue HPV testing due to limited tissue availability.

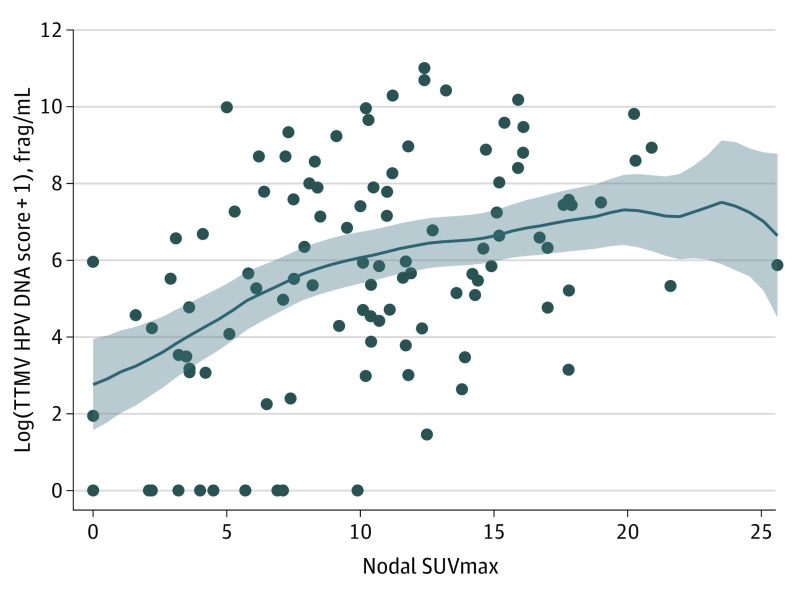

Clinicopathologic Characteristics Associated With Circulating TTMV HPV DNA Detection

Clinical N stage was the clinicopathologic characteristic with the strongest association with detectable TTMV HPV DNA (Kendall τ, 0.032; 95% CI, 0.008-0.057; Table 1 and Figure 1A). Although just 10% of patients presented without nodal disease, few had detectable TTMV HPV DNA (4 of 11 [36%]) compared with the majority of individuals with clinical nodal disease at presentation (N1: 65 of 69 [94%]; N2: 27 of 28 [96%]; N3: 2 of 2 [100%]; overall N1-3: 94 of 99 [95%], for a proportion difference of 59%; 95% CI, 30%-87%). With regard to clinical T stage, patients with T1 tumors at the time of plasma collection were less likely to have detectable TTMV HPV DNA (29 of 37 [78%]) when compared with those with T0 or T2 to T3 tumors (69 of 73 [95%], for a proportion difference of 16%; 95% CI, 2%-30%); however, the association of clinical T stage overall with TTMV HPV DNA was weaker than for clinical N stage (Kendall τ, 0.018; 95% CI, −0.006 to 0.042).

Figure 1. Circulating Tumor Tissue–Modified Viral (TTMV) Human Papillomavirus (HPV) DNA and Clinical Staging.

A, Prevalence of detectable circulating TTMV HPV DNA by clinical nodal stage. B, Circulating TTMV HPV DNA score by clinical nodal stage (log scale). Dark horizontal lines and error whiskers indicate medians and interquartile ranges, respectively. Median TTMV HPV DNA score for N0 is 0. C, Heat map of median circulating TTMV HPV DNA score by clinical tumor and nodal stages, adjusted for excisional diagnostic procedures. Blank boxes indicate no values represented. Numbers denote the number of patients in each group. All stages are based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual, 8th edition. Frag/mL indicates fragment per milliliter.

Among the small subset of 27 patients who underwent definitive surgical treatment after baseline plasma collection, and thus who also had comprehensive pathologic characterization available for analysis, all but 1 patient (20 of 21 [95%]) with pathologically confirmed nodal disease had detectable circulating TTMV HPV DNA compared with just 1 of 6 patients (17%) with pathologically confirmed N0 disease (proportion difference, 79%; 95% CI, 48%-110%) (Table 2). With regard to lymphovascular invasion (LVI), TTMV HPV DNA was detected in all 12 patients (100%) with LVI compared with 9 of 15 patients (60%) without LVI (proportion difference, 40%; 95% CI, 15%-65%). All 12 patients with LVI had at least 1 lymph node metastasis compared with 10 of 15 patients (67%) without LVI (proportion difference, 33%; 95% CI, 9%-57%).

Table 2. Surgical Pathology Characteristics Compared With Circulating TTMV HPV DNA Detectability and Score for a Subset of 27 Patients Who Underwent Surgical Treatment.

| Surgical pathology characteristic | No. in each category (% of total) | No. in each category with detectable TTMV HPV DNA (% of category) | Effect sizea | TTMV HPV DNA score, median (IQR), frag/mLb | Effect sizec | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion difference (95% CI) | Kendall τ (95% CI) | Difference in medians (95% CI) | η2 (95% CI) | ||||

| Total | 27 | 21 (78) | NA | NA | 117 (9 to 1648) | NA | NA |

| Pathologic T staged | |||||||

| T0 | 3 (11) | 2 (67) | NA | 0.027 (−0.077 to 0.132) | 13 (0 to 18 339) | NA | 0.002 (0.00 to 0.01) |

| T1 | 15 (56) | 11 (73) | 93 (0 to 344) | ||||

| T2 | 8 (30) | 7 (88) | 186 (57 to 3845) | ||||

| T3 | 1 (4) | 1 (100) | 12 971 | ||||

| Pathologic N staged | |||||||

| N0 | 6 (22) | 1 (17) | NA | 0.090 (−0.004 to 0.183) | 0 | NA | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.07) |

| N1 | 19 (70) | 18 (95) | 162 (43 to 1648) | ||||

| N2 | 2 (7) | 2 (100) | 7337 (1702 to 12 971) | ||||

| Lymphovascular invasion | |||||||

| No | 15 (56) | 9 (60) | 0.40 (0.15 to 0.65) | NA | 43 (0 to 254) | 232 (59 to 11 623) | NA |

| Yes | 12 (44) | 12 (100) | 274 (130 to 11 632) | ||||

| Extranodal extension | |||||||

| No | 12 (55) | 11 (92) | −0.02 (−0.23 to 0.26) | NA | 117 (45 to 299) | 921.2 (−136 to 12 914) | NA |

| Yes | 10 (45) | 9 (90) | 1039 (13 to 12 971) | ||||

Abbreviations: frag/mL, fragments per milliliter; HPV, human papillomavirus; NA, not applicable; TTMV, tumor tissue–modified viral.

Effect size metrics for comparisons of the proportion of patients with detectable TTMV HPV DNA include proportion difference for characteristics with 2 categories and Kendall τ for characteristics with more than 2 categories.

TTMV scores are rounded to the nearest integer value.

Effect size metrics for comparisons of median TTMV HPV DNA scores include difference in medians for characteristics with 2 categories and η2 for characteristics with more than 2 categories.

Stages are based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual, 8th edition, at time of plasma collection (eg, adjusted for excisional diagnostic procedures).

Other characteristics including sex, age, race, smoking status and pack-years of smoking, tumor site, pathologic T stage, both clinical and pathologic ENE, and NLR were not associated with detectability of circulating TTMV HPV DNA. Patients with p16-positive OPSCCs but without clinical ISH testing available (n = 13) had similar rates of detectable TTMV HPV DNA compared with those with HPV-positive tumors by ISH (n = 97; 85% vs 90%; proportion difference, 5%; 95% CI, −15% to 26%).

Clinicopathologic Characteristics Associated With Circulating TTMV HPV DNA Score

Overall, the median (IQR) TTMV HPV DNA score was 315 (47-2686) frag/mL, with a wide range from 0 to 60 061 frag/mL. Median (IQR) TTMV score increased with higher clinical N stage from 0 (0-12) frag/mL for N0 to 3339 (22-6656) frag/mL for N3 (Table 1 and Figure 1B and C). Regression analysis demonstrated a strong association of N stage with TTMV HPV DNA score (N1: Exp[β], 3.56; 95% CI, 2.66-4.85 and N2-3: Exp[β], 4.02; 95% CI, 2.88-5.53 compared with N0 disease; model 1 in Table 3). In contrast, there was only a weak association with clinical T stage (T2: Exp[β], 1.13; 95% CI, 0.92-1.40 and T3-4: Exp[β], 1.17; 95% CI, 0.92-1.49 compared with T0-1 disease; model 1 in Table 3). Figure 1C demonstrates the marked increase in median TTMV score with clinical N stage more so than with T stage. With regard to sex, a higher median (IQR) TTMV score was observed among men (380 [65-2829] frag/mL) than women (75 [9-193] frag/mL; Exp[β], 1.35; 95% CI, 1.02-1.76). In multivariable analysis including clinical T and N stages and sex, clinical N stage remained strongly associated with higher TTMV score, with Exp(β) of 3.80 (95% CI, 2.76-5.13) for N1 and 3.80 (95% CI, 2.68-5.30) for N2 to N3 compared with N0 disease (model 1 in Table 3).

Table 3. Regression Analysis of Factors Associated With Circulating TTMV HPV DNA Score.

| Characteristic | Association with TTMV HPV DNA score, Exp(β) (95% CI), frag/mLa | |

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

| Model 1 (n = 110) | ||

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Male | 1.35 (1.02-1.76) | 1.20 (0.91-1.56) |

| Clinical T stageb | ||

| T0-1 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| T2 | 1.13 (0.92-1.40) | 1.19 (0.96-1.49) |

| T3-4 | 1.17 (0.92-1.49) | 1.18 (0.98-1.58) |

| Clinical N stageb | ||

| N0 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| N1 | 3.63 (2.66-4.85) | 3.80 (2.76-5.13) |

| N2-3 | 4.02 (2.88-5.53) | 3.80 (2.68-5.30) |

| Model 2 (n = 98) | ||

| HPV genotype | ||

| Non–HPV-16 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| HPV-16 | 1.36 (1.10-1.66) | 1.39 (1.13-1.69) |

| Clinical N stageb | ||

| N0 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| N1 | 1.90 (1.32-2.64) | 1.97 (1.39-2.70) |

| N2-3 | 2.06 (1.41-2.90) | 2.14 (1.49-2.97) |

| Model 3 (n = 108) | ||

| Positron emission tomography | ||

| Primary tumor SUVmax | ||

| <5 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 5-10 | 0.93 (0.68-1.26) | 0.98 (0.72-1.34) |

| 10-15 | 0.90 (0.67-1.21) | 1.09 (0.80-1.47) |

| >15 | 1.22 (0.91-1.63) | 1.23 (0.91-1.64) |

| Nodal SUVmax | ||

| <5 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 5-10 | 1.94 (1.47-2.55) | 2.03 (1.52-2.71) |

| 10-15 | 2.10 (1.62-2.70) | 2.09 (1.59-2.74) |

| >15 | 2.49 (1.87-3.32) | 2.39 (1.76-3.25) |

Abbreviations: frag/mL, fragments per milliliter; HPV, human papillomavirus; SUVmax, maximum standardized uptake value; TTMV, tumor tissue–modified viral.

Estimate of association using generalized linear model of transformed TTMV score with γ distribution and log link.

Stages are based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual, 8th edition.

Notably, non–HPV-16 genotype was observed to yield a lower median (IQR) TTMV score (152 [40-313] frag/mL) when compared with HPV-16 (720 [116-4451] frag/mL; Exp[β], 1.36; 95% CI, 1.10-1.66 for HPV-16 compared with non–HPV16; Table 1, model 2 in Table 3, and eFigure in the Supplement). In bivariable analysis of HPV type and N stage, both variables remained strongly associated with TTMV score (model 2 in Table 3).

Among the 27 surgically treated patients, circulating TTMV HPV DNA scores were higher with greater pathologic N stage and LVI, though with small effect sizes (η2, 0.02; 95% CI, 0.00-0.07) and difference in medians (231.5; 95% CI, 59-11 623) (Table 2). Other clinicopathologic features and NLR were not strongly associated with TTMV HPV DNA scores. Similar results were obtained in a sensitivity analysis excluding patients with undetectable TTMV HPV DNA.

Radiographic Features Associated With Circulating TTMV HPV DNA

Most patients had CT (n = 96 [87%]) and PET-CT (n = 108 [98%]) scans available. On standard contrast-enhanced CT scan, size of the largest cervical lymph node had a stronger association with detectability and score of circulating TTMV HPV DNA than size of the primary tumor (Table 1). An increasing total number of features considered suggestive for ENE was also weakly associated with prevalence and score of TTMV HPV (Table 1), as were several individual imaging features that have been reported to be associated with ENE (eTable 2 in the Supplement). However, there was not a strong association of these CT imaging features with pathologically confirmed ENE for the small subset of 22 surgical patients with nodal metastases.

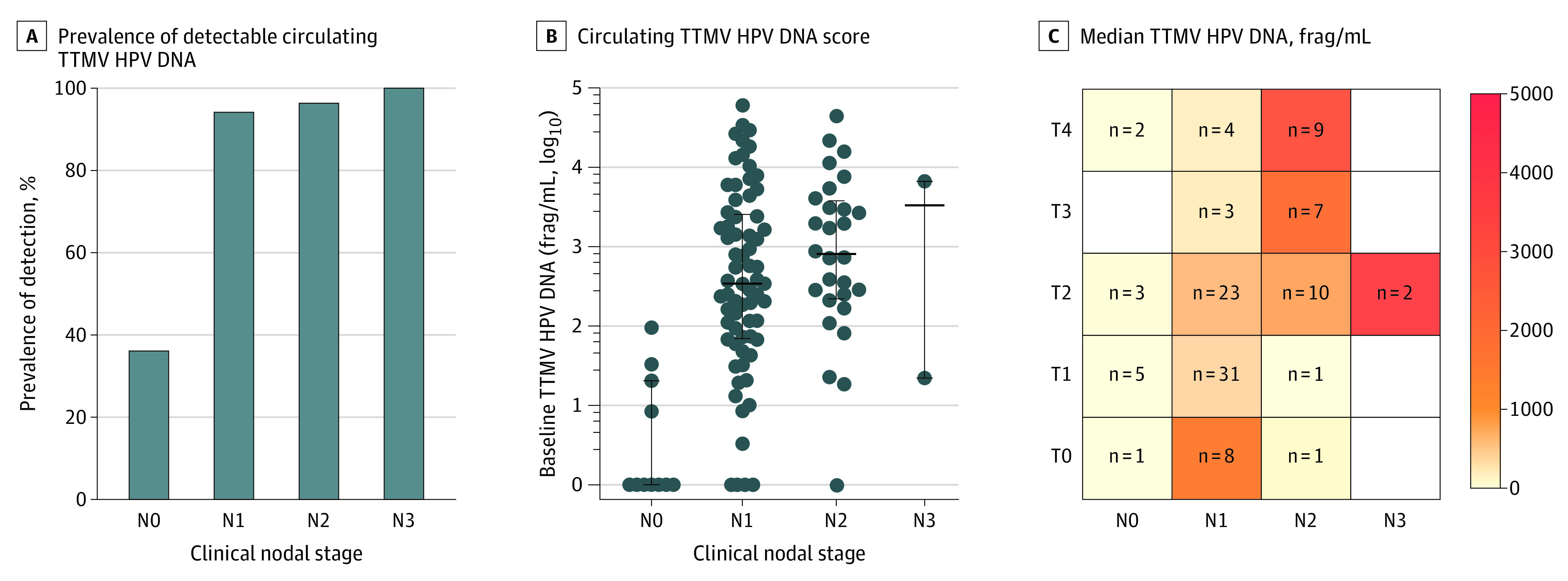

A PET-CT analysis revealed that degree of metabolic activity in both the primary tumor and in the largest cervical lymph node were moderately associated with circulating TTMV HPV score (Table 1). Tumors with higher maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) were more likely to correspond to detectable TTMV HPV DNA (100% for SUVmax >15 compared with 81% for SUVmax <5). However, median TTMV HPV DNA score was highest for those primary tumors with SUVmax that was either low (SUVmax <5) or high (SUVmax >15; Table 1). In contrast, increasing SUVmax in cervical lymph nodes was associated with a progressive increase in both TTMV HPV DNA detection and score (Table 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 2. TTMV HPV DNA Score Compared With Nodal Maximum Standardized Uptake Value (SUVmax) on Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography.

The circulating tumor tissue–modified viral (TTMV) human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA scores are represented with a log scale. The solid line represents kernel-weighted local polynomial smoothing function, and the shaded area represents the 95% CI of this function. Frag/mL indicates fragment per milliliter. Each dot represents a single patient.

In bivariable analysis, increasing SUVmax of both the primary tumor and the cervical nodes were each associated with increasing odds of TTMV HPV DNA detection (per 1 SUV increase: AOR, 1.16 [95% CI, 1.00-1.33] for tumor and 1.48 [95% CI, 1.19-1.84] for nodes). However, when bivariable analysis was performed for TTMV HPV DNA score, the association of nodal SUVmax with TTMV HPV DNA score was strongly statistically significant (Exp[β], 2.39 [95% CI, 1.76-3.25] for nodal SUVmax >15 compared with SUVmax <5), while the association with tumor SUVmax was not (Exp[β], 1.23 [95% CI, 0.91-1.64] for tumor SUVmax >15 compared with SUVmax <5; model 3 in Table 3).

Sensitivity Analysis of HPV-16 Genotype Only

Given higher TTMV HPV DNA scores for HPV-16, sensitivity analysis was performed including only patients with HPV-16 genotypes (n = 95), as determined by TTMV HPV DNA testing of plasma (n = 86) or tumor tissue (n = 5), or ISH testing of tumor tissue (n = 4; considered HPV-16 if HPV-16/18 positive). Results were similar to the larger cohort (eTable 3 in the Supplement), with slight differences in that the association of clinical T stage on CT scan with circulating TTMV HPV DNA detection was slightly stronger than in the full cohort (Kendall τ, 0.028; 95% CI, 0.001-0.056; eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Discussion

In this comprehensive analysis of pretreatment circulating TTMV HPV DNA among patients with HPV-positive OPSCC, cervical lymph node metastatic tumor burden was found across multiple measures to be strongly associated with TTMV HPV DNA presence and score. Associations of circulating TTMV HPV DNA with other clinicopathologic characteristics, including primary tumor features, were notably weaker. These data inform the understanding of circulating TTMV HPV DNA and its wide interpatient variability as a biomarker for HPV-positive OPSCC and have important implications for how it may be used in the diagnostic, surveillance, and screening settings. Further exploration of the mechanisms underlying this association is warranted.

Circulating TTMV HPV DNA was progressively more prevalent and had progressively higher median scores, with measures of nodal disease including increasing nodal stage, longer diameter of largest node, higher number of CT imaging features suggestive for ENE, and increasing metabolic activity as measured by nodal SUVmax. The association of LVI with TTMV HPV DNA in the subset of surgically treated patients, though limited by the small size of the surgical cohort, is congruent with these associations, together suggesting that access to the lymphatic space may be a critical determinant of whether, and to what degree, tumor DNA sheds into the circulation. Lymphovascular invasion has also been associated with cell-free DNA in other cancer types.20,21,22,23,24 The collinearity of LVI and nodal metastases in this small, surgically treated cohort prevented analysis of the relative importance of these 2 variables, but further exploration in larger surgical cohorts would be of interest.

Other groups have also reported an association of ctHPVDNA with nodal disease.3,11,25 This is concordant with the present data, with the caveat that the commercial TTMV HPV DNA assay used herein has not been directly compared with other ctHPVDNA assays, and the extent to which these findings may be generalized to analyses using other methods is unknown. The commercial assay used in this analysis is based on the assay developed by Chera et al,4 who did also report higher ctHPVDNA levels among patients with American Joint Committee on Cancer staging manual, 8th edition, stage N1 disease compared with N0. However, Chera et al also reported a trend toward lower levels among those with N2 disease, whereas we observed progressively higher TTMV HPV DNA values with increasing nodal stage. Reasons underlying this discrepancy are unclear but may relate to slight differences in study populations because Chera et al included only patients undergoing chemoradiation.

The consistent, strong association between nodal disease and plasma TTMV HPV DNA prevalence and score is of critical importance when considering the role of this biomarker in HPV-positive OPSCC diagnosis and, potentially, screening. More than half of patients without clinical nodal disease in the present cohort did not have detectable TTMV HPV DNA, and more than half of patients with undetectable TTMV HPV DNA were clinically N0. The fact that 5 of 6 patients with pathologically confirmed N0 disease had undetectable TTMV HPV DNA raises the question of whether the 4 nonsurgically treated patients with clinical N0 disease with detectable circulating TTMV HPV DNA may have, in fact, harbored occult nodal metastases.

The present data also suggest that the high reported sensitivity (approximately 90%)4 of circulating TTMV HPV DNA for HPV-positive OPSCC may actually be even higher among patients with existing nodal disease, but conversely is closer to 50% among those who are clinically N0. Thus, in the diagnostic setting, circulating TTMV HPV DNA testing may be useful for evaluating an adult presenting with a neck mass but would be lower yield when evaluating an adult with another symptom concerning for HPV-positive OPSCC, such as palatine or lingual tonsil asymmetry. In the screening setting, though we previously reported that TTMV HPV DNA is detectable in plasma several years prior to diagnosis for some patients,9 these data suggest that it may not be detectable at the earliest stages of disease for many individuals. Indeed, in our previous report, all 3 individuals whose prediagnostic plasma harbored detectable TTMV HPV DNA had nodal metastases at presentation. Future studies should evaluate whether local sampling of the oropharynx with oral rinses, known to detect HPV DNA in a variable majority of patients with HPV-positive OPSCC depending on the methodology,26,27,28,29 may serve as a complementary assay to plasma testing in individuals without nodal metastases. Finally, the role of circulating TTMV HPV DNA monitoring for disease surveillance after treatment for the minority of patients with undetectable baseline levels is unknown and warrants further study to elaborate.

The prognostic significance of baseline TTMV HPV DNA score alone is not clear. Higher baseline values have been associated with more advanced nodal disease as reported in this study; however, nodal metastases in HPV-positive disease are less of a harbinger for poor prognosis than in HPV-negative head and neck cancers.30 Recent studies suggest that the trajectory of ctHPVDNA during and after treatment is much more clinically relevant than the baseline value alone.4,11,13,26 There is an urgent need to further delineate how dynamic changes in circulating TTMV HPV DNA reflect disease biology and response to treatment.

With regard to HPV genotype, the small subset of HPV-positive OPSCCs in this cohort that were caused by HPV types other than 16 had considerably lower circulating TTMV HPV DNA scores than those caused by HPV-16. While an emerging body of evidence supports biologic heterogeneity among HPV-positive OPSCCs by HPV genotype,31,32,33 the difference in TTMV HPV DNA score reported herein should be interpreted with caution because it likely also reflects differential accuracies of the assay used for HPV-16 vs other genotypes, consistent with the different genotype-specific detectability thresholds established by the commercial laboratory (see Methods).

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study include a contemporary cohort and the use of a clinically available assay. Although the large cohort allowed for robust analysis of many clinicopathologic features, certain subgroups such as patients with undetectable circulating TTMV HPV DNA, clinical stage N0 cancer, surgical treatment, and non–HPV-16 genotypes were small, leading to imprecise effect size estimates with wide confidence intervals and preventing definitive conclusions. Furthermore, inferences regarding the molecular underpinnings of circulating TTMV HPV DNA attributes were limited without genomic data such as integration status, which should be further explored. Whether these findings are generalizable to other ctHPVDNA assays is unknown.

Conclusions

In this cross-sectional study, circulating TTMV HPV DNA detection and score were strongly associated with nodal disease burden in HPV-positive OPSCC. These findings inform the understanding of this dynamic biomarker, with implications for biomarker-based diagnosis and screening.

eTable 1. Characteristics of patients with undetectable circulating TTMV-HPV DNA

eTable 2. Radiographic features of extranodal extension compared with circulating TTMV-HPV DNA detectability and score

eTable 3. Sensitivity analysis including only HPV16-positive OPSCCs of clinicopathologic and radiographic characteristics compared with circulating TTMV-HPV16 DNA detectability and score

eFigure. Circulating TTMV-HPV DNA score by HPV genotype

References

- 1.Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. Worldwide trends in incidence rates for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(36):4550-4559. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.3870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y, Fakhry C, D’Souza G. Projected association of human papillomavirus vaccination with oropharynx cancer incidence in the US, 2020-2045. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(10):e212907. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.2907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siravegna G, O’Boyle CJ, Varmeh S, et al. Cell-free HPV DNA provides an accurate and rapid diagnosis of HPV-associated head and neck cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28(4):719-727. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-3151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chera BS, Kumar S, Beaty BT, et al. Rapid clearance profile of plasma circulating tumor HPV type 16 DNA during chemoradiotherapy correlates with disease control in HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(15):4682-4690. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tewari SR, D’Souza G, Troy T, et al. Association of plasma circulating tumor HPV DNA with HPV-related oropharynx cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;148(5):488-489. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2022.0159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chera BS, Kumar S, Shen C, et al. Plasma circulating tumor HPV DNA for the surveillance of cancer recurrence in HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(10):1050-1058. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanna GJ, Supplee JG, Kuang Y, et al. Plasma HPV cell-free DNA monitoring in advanced HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(9):1980-1986. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berger BM, Hanna GJ, Posner MR, et al. Detection of occult recurrence using circulating tumor tissue modified viral HPV DNA among patients treated for HPV-driven oropharyngeal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. Published online May 16, 2022. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-0562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rettig EM, Faden DL, Sandhu S, et al. Detection of circulating tumor human papillomavirus DNA before diagnosis of HPV-positive head and neck cancer. Int J Cancer. 2022;151(7):1081-1085. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mattox AK, D’Souza G, Khan Z, et al. Comparison of next generation sequencing, droplet digital PCR, and quantitative real-time PCR for the earlier detection and quantification of HPV in HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2022;128:105805. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2022.105805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao Y, Haring CT, Brummel C, et al. Early HPV ctDNA kinetics and imaging biomarkers predict therapeutic response in p16+ oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28(2):350-359. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-2338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Routman DM, Kumar S, Chera BS, et al. Detectable postoperative circulating tumor human papillomavirus DNA and association with recurrence in patients with HPV-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2022;113(3):530-538. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2022.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Boyle CJ, Siravegna G, Varmeh S, et al. Cell-free human papillomavirus DNA kinetics after surgery for human papillomavirus-associated oropharyngeal cancer. Cancer. 2022;128(11):2193-2204. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park SI, Guenette JP, Suh CH, et al. The diagnostic performance of CT and MRI for detecting extranodal extension in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review and diagnostic meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2021;31(4):2048-2061. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07281-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carlton JA, Maxwell AW, Bauer LB, et al. Computed tomography detection of extracapsular spread of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in metastatic cervical lymph nodes. Neuroradiol J. 2017;30(3):222-229. doi: 10.1177/1971400917694048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faraji F, Rettig EM, Tsai HL, et al. The prevalence of human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal cancer is increasing regardless of sex or race, and the influence of sex and race on survival is modified by human papillomavirus tumor status. Cancer. 2019;125(5):761-769. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noor A, Mintz J, Patel S, et al. Predictive value of computed tomography in identifying extracapsular spread of cervical lymph node metastases in p16 positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2019;63(4):500-509. doi: 10.1111/1754-9485.12888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. John Wiley & Sons; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen R. Statistics and Experimental Design for Psychologists: A Model Comparison Approach. World Scientific Publishing; 2017. doi: 10.1142/q0019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Umetani N, Giuliano AE, Hiramatsu SH, et al. Prediction of breast tumor progression by integrity of free circulating DNA in serum. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(26):4270-4276. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.9493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hsieh CC, Hsu HS, Chang SC, Chen YJ. Circulating cell-free DNA levels could predict oncological outcomes of patients undergoing esophagectomy for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(12):2131. doi: 10.3390/ijms17122131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumari S, Husain N, Agarwal A, et al. Diagnostic value of circulating free DNA integrity and global methylation status in gall bladder carcinoma. Pathol Oncol Res. 2019;25(3):925-936. doi: 10.1007/s12253-017-0380-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shyr BU, Shyr BS, Chen SC, Chang SC, Shyr YM, Wang SE. Circulating cell-free DNA as a prognostic biomarker in resectable ampullary cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(10):2313. doi: 10.3390/cancers13102313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamamoto Y, Uemura M, Nakano K, et al. Increased level and fragmentation of plasma circulating cell-free DNA are diagnostic and prognostic markers for renal cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2018;9(29):20467-20475. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.24943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao H, Banh A, Kwok S, et al. Quantitation of human papillomavirus DNA in plasma of oropharyngeal carcinoma patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(3):e351-e358. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.05.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rettig EM, Wentz A, Posner MR, et al. Prognostic implication of persistent human papillomavirus type 16 DNA detection in oral rinses for human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(7):907-915. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.D’Souza G, Clemens G, Troy T, et al. Evaluating the utility and prevalence of HPV biomarkers in oral rinses and serology for HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2019;12(10):689-700. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-19-0185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fakhry C, Blackford AL, Neuner G, et al. Association of oral human papillomavirus DNA persistence with cancer progression after primary treatment for oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(7):985-992. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.0439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerndt SP, Ramirez RJ, Wahle BM, et al. Evaluating a clinically validated circulating tumor HPV DNA assay in saliva as a proximal biomarker in HPV+ oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(suppl 15):6063. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.6063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lydiatt WM, Patel SG, O’Sullivan B, et al. Head and Neck cancers-major changes in the American Joint Committee on cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):122-137. doi: 10.3322/caac.21389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chatfield-Reed K, Gui S, O’Neill WQ, Teknos TN, Pan Q. HPV33+ HNSCC is associated with poor prognosis and has unique genomic and immunologic landscapes. Oral Oncol. 2020;100:104488. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.104488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bratman SV, Bruce JP, O’Sullivan B, et al. Human papillomavirus genotype association with survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(6):823-826. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.6587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazul AL, Rodriguez-Ormaza N, Taylor JM, et al. Prognostic significance of non-HPV16 genotypes in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2016;61:98-103. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Characteristics of patients with undetectable circulating TTMV-HPV DNA

eTable 2. Radiographic features of extranodal extension compared with circulating TTMV-HPV DNA detectability and score

eTable 3. Sensitivity analysis including only HPV16-positive OPSCCs of clinicopathologic and radiographic characteristics compared with circulating TTMV-HPV16 DNA detectability and score

eFigure. Circulating TTMV-HPV DNA score by HPV genotype