This cohort study investigates the association among different immunosuppressive regimens for grade 3 and higher immune-related adverse events with overall survival and progression-free survival in a homogeneous cohort of patients with advanced melanoma who were treated with first-line ipilimumab and nivolumab.

Key Points

Question

Is there an association among different immunosuppressive treatments for grade 3 and higher immune-related adverse events (irAEs) and progression-free survival or overall survival in patients with advanced melanoma treated with first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab combination therapy?

Findings

In this cohort study including 771 patients with advanced melanoma who were treated with ipilimumab and nivolumab, 350 patients were treated with immunosuppression for severe irAEs. Use of second-line immunosuppression, irrespective of the type, was associated with impaired progression-free survival and overall survival.

Meaning

These results suggest harmful effects of escalated immunosuppression for irAEs, which warrants further investigation to identify detrimental factors within current irAE management approaches.

Abstract

Importance

Management of checkpoint inhibitor–induced immune-related adverse events (irAEs) is primarily based on expert opinion. Recent studies have suggested detrimental effects of anti–tumor necrosis factor on checkpoint-inhibitor efficacy.

Objective

To determine the association of toxic effect management with progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and melanoma-specific survival (MSS) in patients with advanced melanoma treated with first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab combination therapy.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This population-based, multicenter cohort study included patients with advanced melanoma experiencing grade 3 and higher irAEs after treatment with first-line ipilimumab and nivolumab between 2015 and 2021. Data were collected from the Dutch Melanoma Treatment Registry. Median follow-up was 23.6 months.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The PFS, OS, and MSS were analyzed according to toxic effect management regimen. Cox proportional hazard regression was used to assess factors associated with PFS and OS.

Results

Of 771 patients treated with ipilimumab and nivolumab, 350 patients (median [IQR] age, 60.0 [51.0-68.0] years; 206 [58.9%] male) were treated with immunosuppression for severe irAEs. Of these patients, 235 received steroids alone, and 115 received steroids with second-line immunosuppressants. Colitis and hepatitis were the most frequently reported types of toxic effects. Except for type of toxic effect, no statistically significant differences existed at baseline. Median PFS was statistically significantly longer for patients treated with steroids alone compared with patients treated with steroids plus second-line immunosuppressants (11.3 [95% CI, 9.6-19.6] months vs 5.4 [95% CI, 4.5-12.4] months; P = .01). Median OS was also statistically significantly longer for the group receiving steroids alone compared with those receiving steroids plus second-line immunosuppressants (46.1 months [95% CI, 39.0 months-not reached (NR)] vs 22.5 months [95% CI, 36.5 months-NR]; P = .04). Median MSS was also better in the group receiving steroids alone compared with the group receiving steroids plus second-line immunosuppressants (NR [95% CI, 46.1 months-NR] vs 28.8 months [95% CI, 20.5 months-NR]; P = .006). After adjustment for potential confounders, patients treated with steroids plus second-line immunosuppressants showed a trend toward a higher risk of progression (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.40 [95% CI, 1.00-1.97]; P = .05) and had a higher risk of death (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.54 [95% CI, 1.03-2.30]; P = .04) compared with those receiving steroids alone.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study, second-line immunosuppression for irAEs was associated with impaired PFS, OS, and MSS in patients with advanced melanoma treated with first-line ipilimumab and nivolumab. These findings stress the importance of assessing the effects of differential irAE management strategies, not only in patients with melanoma but also other tumor types.

Introduction

The introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has greatly improved the prognosis of patients diagnosed with advanced melanoma.1,2 However, blocking immunological checkpoints, such as cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) or programmed cell death 1 (PD-1), may lead to immune-related adverse events (irAEs). In the phase 3 CheckMate 067 trial,3 96% of patients experienced any irAE, and 59% experienced grade 3 or higher irAEs when treated with a combination of CTLA-4 and PD-1 antibodies.

Because irAEs result from immune activation, the occurrence of irAEs has been hypothesized to be associated with improved ICI efficacy. Data on this toxicity-efficacy relationship are inconsistent, prone to immortal time bias, and heterogeneous in cancer type, ICI regimen, and severity of toxic effects. Nevertheless, an increasing body of evidence seems to support this hypothesis.4,5,6,7,8,9

The management of irAEs is based mainly on expert opinion,10 and data on the effect of immunosuppressive therapy on ICI efficacy are limited. Although administration of steroids for irAEs has generally been considered safe,11,12 a more recent study questions this to be the case for early high-dose steroids.13 The effect of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blockade on the survival of patients with advanced melanoma has been a matter of debate.14,15,16 A recent study by our group9 showed an association between the use of TNF blockade for irAEs and impaired survival in a mixed population of patients with advanced melanoma treated with ipilimumab, anti–PD-1 therapy, or combination ipilimumab and nivolumab. An important remaining question is if a potentially harmful effect could be attributed to anti-TNF specifically or regarded as the result of escalated and long-term immunosuppression. In this cohort study, we investigated the association among different immunosuppressive regimens for grade 3 and higher irAEs with overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in a more homogeneous cohort of patients with advanced melanoma, all treated with first-line ipilimumab and nivolumab.

Methods

Study Design

For this study, we used data from the Dutch Melanoma Treatment Registry (DMTR). The DMTR has prospectively registered data of all patients with unresectable stage IIIc and IV melanoma in the Netherlands since 2012. The data in the DMTR are registered by independent data managers who are trained annually. To further ensure the data quality, patients’ data are checked by their treating physicians.17

All patients with advanced cutaneous melanoma treated with first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab combination therapy registered in the DMTR between April 2015 and December 2021 were included in this study, with survival analyses focusing on patients who experienced severe irAEs. We stratified patients according to their management of toxic effects: steroids alone vs steroids with any second-line immunosuppressant. For the second analysis, the latter group of patients receiving steroids with any second-line immunosuppressant was further divided into those receiving steroids with anti-TNF vs those receiving steroids with other second-line immunosuppressants (excluding anti-TNF). Other immunomodulating medications consisted of mycophenolic acid, tacrolimus, and other nonspecified immunosuppressants.

Baseline characteristics, reasons for treatment discontinuation, and survival outcomes were compared between the different groups. For this study, the data set cutoff date was December 14, 2021. Research using DMTR data was approved by the medical ethical committee and was not deemed subject to the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act in compliance with Dutch regulations, thus patient informed consent was not required.

Patient Characteristics

The registered patient and tumor characteristics at diagnosis that were used for this analysis included (1) age at diagnosis, (2) sex, (3) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status, (4) lactate dehydrogenase levels, (5) liver metastasis, (6) brain metastasis, (7) stage according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer, 8th edition,18 and (8) BRAF, NRAS, and KIT variation status. Furthermore, data on the type of toxic effects and treatments used to manage toxic effects were registered.

Response evaluation was determined by the treating physician and was based on the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors, version 1.1.19 Progression-free survival was calculated from the start of systemic therapy until progression or death by any cause. Overall survival was calculated from the start of systemic therapy until death by any cause or last moment of follow-up. Patients not reaching the end point were censored at the date of the last contact. Melanoma-specific survival was calculated from the start of systemic therapy until melanoma-related death. Patients dying of other causes were censored.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Pearson χ2 test was used to compare categorical variables, and the Wilcoxon test was used for continuous variables. Median follow-up time was estimated from the date of the first visit using the reversed Kaplan-Meier method.20 Median PFS and OS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to perform a multivariable regression analysis to assess factors associated with PFS and OS. Comparisons were considered statistically significant for 2-sided P < .05. Data handling and statistical analyses were performed using Rstudio, version 4.0.2 (R Foundation),21 packages survival,22 and survminer.23

Results

Patient Characteristics

Of 771 patients treated with first-line combination ipilimumab and nivolumab, 385 patients (49.9%) experienced grade 3 or higher irAEs. Eighty-five percent (n = 327) of these patients were not included in our previous study.9 Of the patients experiencing grade 3 or higher irAEs, 235 received steroids alone, and 115 received steroids plus any second-line immunosuppressant. Patients treated with steroids plus any second-line immunosuppressant more often experienced colitis than patients who received steroids only (80 [69.6%] vs 66 [28.1%]; P < .001), which was the opposite for hepatitis (36 [31.3%] vs 103 [43.8%]; P = .03), and endocrine-related toxic effects (6 [5.2%] vs 37 [15.7%]; P = .008). Colitis (n = 146) and hepatitis (n = 139) were the most frequently reported toxic effects. There were no other statistically significant differences at baseline between the 2 groups (Table). Of the 115 patients treated for their irAE(s) with any second-line immunosuppressant, 67 received steroids plus anti-TNF and 35 received steroids plus other second-line immunosuppressants excluding anti-TNF.

Table. Patient Characteristics Stratified by Management of Toxic Effects in Patients With Advanced Melanoma Treated With First-line Ipilimumab and Nivolumab.

| Characteristic | Treatment, No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steroids (n = 235) | Steroids + any second-line immunosuppressant (n = 115) | ||

| Age, y | |||

| <70 | 187 (79.6) | 84 (73.0) | .22 |

| ≥70 | 48 (20.4) | 31 (27.0) | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 60.0 (52.0-68.0) | 60.0 (50.0-70.0) | .95 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 101 (43.0) | 43 (37.4) | .38 |

| Male | 134 (57.0) | 72 (62.6) | |

| ECOG PS | |||

| 0 | 129 (54.9) | 53 (46.1) | .39 |

| 1 | 82 (34.9) | 49 (42.6) | |

| ≥2 | 14 (6.0) | 6 (5.2) | |

| Liver metastases | |||

| No | 157 (66.8) | 74 (64.3) | .52 |

| Yes | 76 (32.3) | 41 (35.7) | |

| Brain metastases | |||

| No | 142 (60.4) | 61 (53.0) | .47 |

| Yes (asymptomatic) | 61 (26.0) | 34 (29.6) | |

| Yes (symptomatic) | 31 (13.2) | 20 (17.4) | |

| Organ sites | |||

| <3 | 112 (47.7) | 47 (40.9) | .37 |

| ≥3 | 122 (51.9) | 68 (59.1) | |

| Unknown | 1 (0.4) | 0 | |

| AJCC, 8th edition, stage | |||

| IIIc unresectable | 12 (5.1) | 5 (4.3) | .32 |

| IV-M1a | 3 (1.3) | 4 (3.5) | |

| IV-M1b | 20 (8.5) | 5 (4.3) | |

| IV-M1c | 107 (45.5) | 47 (40.9) | |

| IV-M1d | 92 (39.1) | 54 (47.0) | |

| LDH levels | |||

| Normal | 119 (50.6) | 60 (52.2) | .72 |

| 250-500 U/L | 80 (34.0) | 39 (33.9) | |

| >500 U/L | 31 (13.2) | 14 (12.2) | |

| Gene variation | |||

| BRAF | 90 (38.3) | 54 (47.0) | .15 |

| NRAS | 70 (29.8) | 33 (28.7) | .93 |

| KIT | 3 (1.3) | 1 (0.9) | >.99 |

| Toxic effect typea | |||

| Colitis | 66 (28.1) | 80 (69.6) | <.001 |

| Hepatitis | 103 (43.8) | 36 (31.3) | .03 |

| CNS toxic effect or neuropathy | 15 (6.4) | 7 (6.1) | >.99 |

| Nephritis | 17 (7.2) | 3 (2.6) | .13 |

| Pneumonitis | 21 (8.9) | 4 (3.5) | .10 |

| Endocrine related | 37 (15.7) | 6 (5.2) | .008 |

| Dermatitis | 32 (13.6) | 7 (6.1) | .06 |

| Cardiac toxic effect | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | .81 |

| Otherb | 10 (4.3) | 2 (1.7) | .37 |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; CNS, central nervous system; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

SI conversion factor: To convert LDH to microkatals per liter, multiply by 0.0167.

Patients may experience multiple toxic effects.

Other consisted of any toxic effects outside the categories mentioned.

Patient characteristics of these groups are summarized in eTable 1 in the Supplement. Specification of the irAE management strategy of the group receiving steroids plus other second-line immunosuppressants excluding anti-TNF is summarized in eTable 2 in the Supplement. Thirteen patients were excluded from this last analysis because they received both anti-TNF and other second-line immunosuppressants. Management strategies for these patients are summarized in eTable 3 in the Supplement. Median follow-up was 23.6 months.

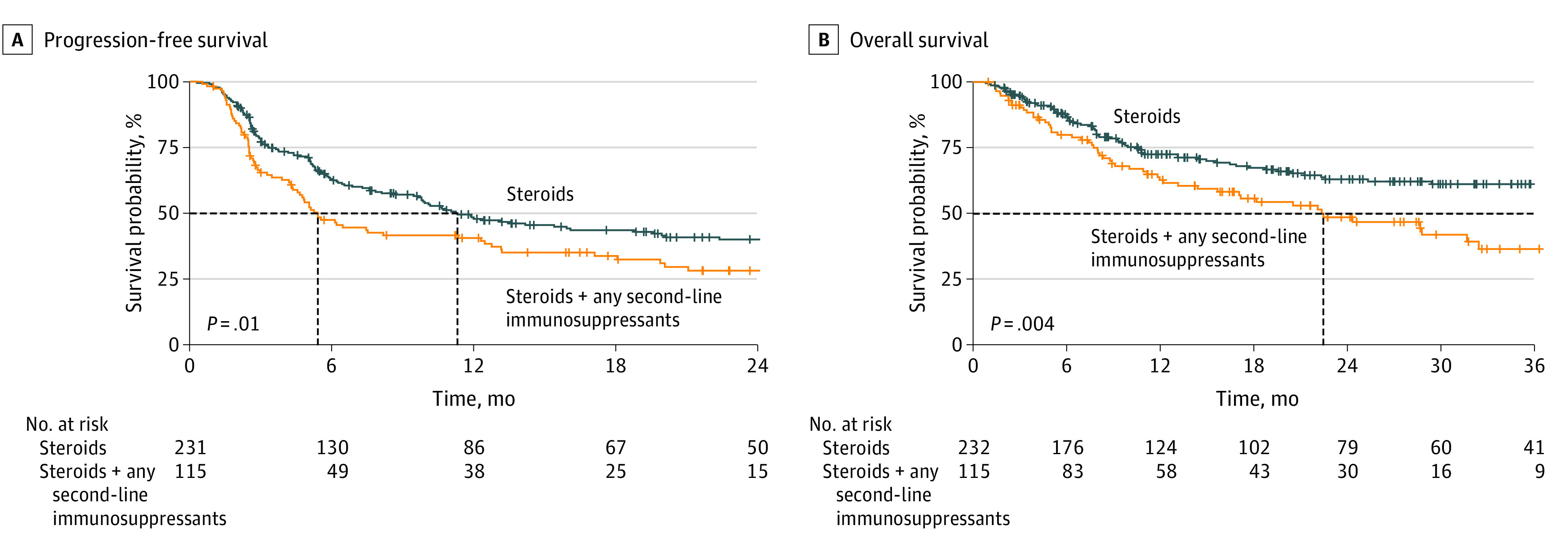

Progression-Free Survival

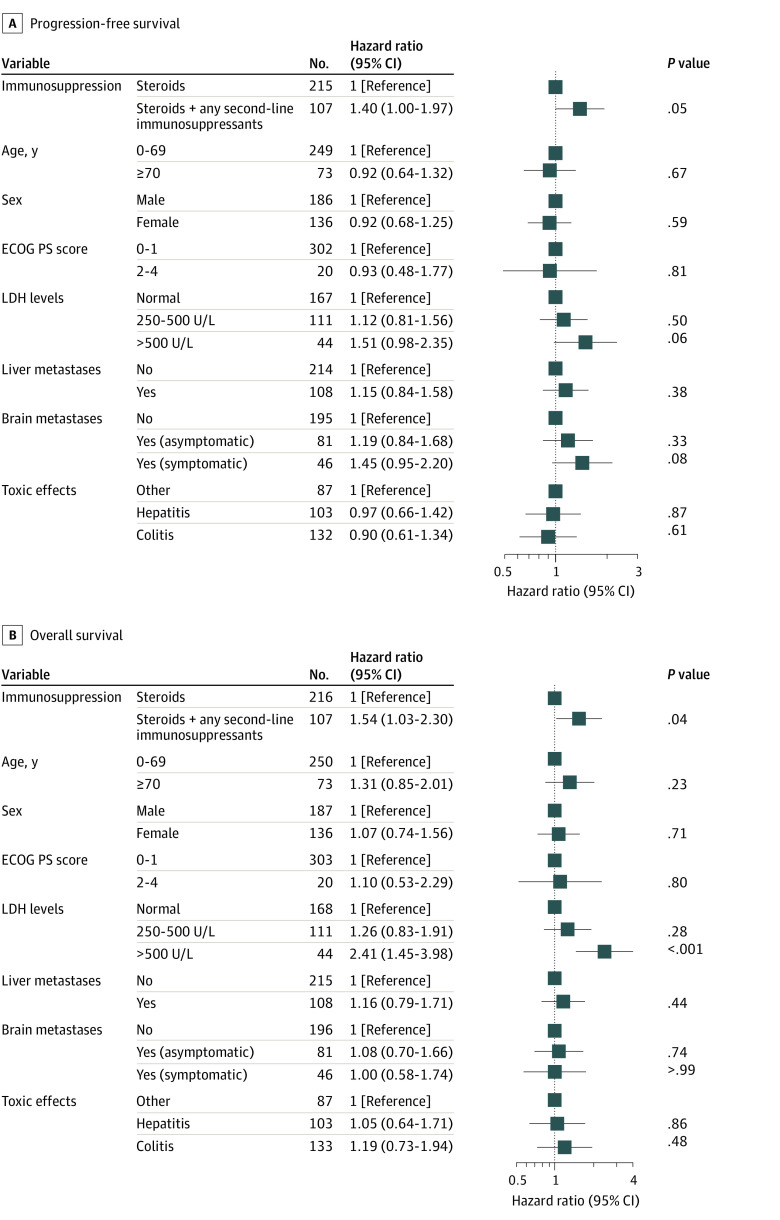

Patients treated with steroids alone had a statistically significant longer median PFS (11.3 [95% CI, 9.6-19.5] months) compared with patients treated with steroids plus any second-line immunosuppressant (5.4 [95% CI, 4.5-12.4] months; hazard ratio [HR], 1.43 [95% CI, 1.07-1.90]; P = .01; Figure 1A). In multivariable analysis, there was a strong trend of a higher risk of progression or death for patients receiving any second-line immunosuppressant next to steroids (adjusted HR [aHR], 1.40 [95% CI, 1.00-1.97]; P = .05; Figure 2A).

Figure 1. Survival Stratified by Management of Toxic Effects in Patients With Advanced Melanoma Treated With First-line Ipilimumab and Nivolumab.

The dashed lines represent the median survivals.

Figure 2. Cox Proportional Hazard Model of Survival Stratified by Management of Toxic Effects in Patients With Advanced Melanoma Treated With First-line Ipilimumab and Nivolumab.

ECOG PS indicates Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase. To convert LDH to microkatals per liter, multiply by 0.0167.

Progression-free survival was statistically significantly longer in the steroids-only group compared with the groups receiving steroids plus anti-TNF (median PFS, 5.4 [95% CI, 4.7-13.1] months; HR, 1.44 [95% CI, 1.02-2.02]; P = .04) and steroids plus other immunosuppressants excluding anti-TNF (median PFS, 4.3 [95% CI, 2.5-13.2] months; HR, 1.65 [95% CI, 1.07-2.56]; P = .02). No statistically significant difference in PFS existed between the groups receiving steroids plus anti-TNF and steroids plus other second-line immunosuppressants excluding anti-TNF (HR, 1.17 [95% CI, 0.71-1.92]; P = .54; eFigure 1A in the Supplement). Multivariable analysis showed no statistically significantly higher risk of progression or death for patients receiving steroids plus anti-TNF (aHR, 1.44 [95% CI, 0.92-2.26]; P = .11) but did show a higher risk of progression or death for patients receiving steroids plus other second-line immunosuppressants excluding anti-TNF compared with steroids only (aHR, 1.62 [95% CI, 1.02-2.57]; P = .04; eFigure 2A in the Supplement).

Overall Survival

Patients treated with steroids alone had a statistically significant longer median OS (46.1 months [95% CI, 39.0 months-not reached [NR]) compared with patients receiving steroids plus any second-line immunosuppressant (median OS, 22.5 months [95% CI, 36.5 months-NR]; HR, 1.64 [95% CI, 1.16-2.32]; P = .005; Figure 1B). After adjusting for potential confounders, the risk of death remained statistically significantly higher for patients receiving any second-line immunosuppressant next to steroids (aHR, 1.54 [95% CI, 1.03-2.30]; P = .04; Figure 2B).

Median OS was also statistically significantly longer for patients receiving steroids alone compared with steroids plus anti-TNF (median OS, 28.7 months [95% CI, 12.2 months-NR]; HR, 1.62 [95% CI, 1.07-2.46]; P = .02), but not compared with steroids plus other second-line immunosuppressants excluding anti-TNF (median OS, 22.4 months [95% CI, 13.2 months-NR]; HR, 1.59 [95% CI, 0.95-2.65]; P = .08). No statistically significant difference in OS was found between patients receiving steroids plus anti-TNF and steroids plus other second-line immunosuppressants excluding anti-TNF (HR, 0.99 [95% CI, 0.56-1.76]; P = .97; eFigure 1B in the Supplement). After adjusting for potential confounders, the differences in risk of death between these subgroups were no longer statistically significant (eFigure 2B in the Supplement). The observed trends in OS were also seen for melanoma-specific survival (eFigures 3 and 4 in the Supplement).

Treatment Duration and Discontinuation

In the group receiving steroids plus any second-line immunosuppression, median (IQR) treatment duration (TD) was 44 (21-102) days. This was not statistically significantly different from patients treated with steroids plus any second-line immunosuppressants (median [IQR] TD, 40 [21-63] days). Patients treated with steroids plus anti-TNF had a median (IQR) TD of 42 (21-63) days, and patients treated with steroids plus other second-line immunosuppressants excluding anti-TNF had a median (IQR) TD of 21 (21-44) days.

Statistically significantly more patients discontinued treatment due to toxic effects in the group receiving steroids plus any second-line immunosuppressants (n = 102 [88.7%]) compared with patients receiving steroids only (n = 171 [72.8%]) (P = .02; eTable 4 in the Supplement). There were no statistically significant differences in reasons for treatment discontinuation among patients receiving steroids alone, steroids with anti-TNF, or steroids with other second-line immunosuppressants excluding anti-TNF, but this could be a consequence of small patient numbers (eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Discussion

In this nationwide cohort study, we showed that patients with melanoma who received second-line immunosuppressants for toxic effects had a shorter PFS and OS than those whose irAEs were managed with steroids only. While we previously demonstrated the detrimental effects of anti-TNF in this setting,9 the current data demonstrate inferior survival for all patients receiving second-line immunosuppressants. Because the size of the subgroups of patients receiving anti-TNF or other immunosuppressants (excluding anti-TNF) were small, the present data are inconclusive on whether this impaired survival is associated with the use of anti-TNF specifically or accelerated immunosuppression in general.

Controversy exists regarding the effect of TNF inhibition as irAE treatment on ICI efficacy. Our previous study showed that patients with melanoma and severe irAEs treated with TNF inhibition had worse OS than patients who only received steroids.9 Analyzing 1250 patients with melanoma treated with first-line ICIs, we showed that the 312 patients who experienced severe ICI-related toxic effects had a statistically significantly prolonged survival. The median OS of patients experiencing grade 3 or higher irAEs was 23 months compared with 15 months for patients without severe toxic effects (aHR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.63-0.93). Among patients with severe toxic effects, median OS was 17 months in patients who were treated with anti-TNF plus steroids compared with 27 months in patients who received steroids only (aHR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.03-2.51). In contrast with the present current homogeneous cohort, our previous study contained a mix of ICI treatments, with most patients receiving anti–CTLA-4 or anti–PD-1 monotherapy, which raised concerns about residual confounding.24 The homogeneous cohort of patients treated with first-line ipilimumab and nivolumab allowed us to evaluate differences in PFS. Comparing patients with and without irAEs was not the focus of the current study. However, we once more found that patients with severe irAEs treated with steroids only had a statistically significant better PFS and OS than patients not experiencing severe irAEs. This survival benefit was not found for patients whose irAEs were managed with second-line immunosuppressants (eFigure 5 in the Supplement).

Two small retrospective studies did not show a difference in survival or time to treatment failure between patients with advanced cancer and ICI-induced colitis treated with steroids alone or steroids plus TNF inhibition.25,26 However, with only 35 and 36 patients treated with anti-TNF, respectively, these studies were underpowered to observe meaningful effects of immunosuppressants on ICI efficacy. Two other small studies have described the effects of anti-TNF for ICI-related colitis in 27 and 19 patients, respectively.27,28 Although the authors concluded that compared with historical controls, anti-TNF did not appear to negatively influence survival, their median OS of 9 and 12 months, respectively, compared unfavorably with OS in recent studies.2

Zou and colleagues29 conducted a retrospective comparison in a heterogeneous cohort of patients with cancer who received TNF inhibition (infliximab), vedolizumab (an integrin inhibitor), or both as second-line immunosuppressants for colitis or diarrhea induced by anti–PD-1, anti–CTLA-4, or combined ICIs. They found an inferior response and OS of patients treated with infliximab compared with vedolizumab. As the authors acknowledge, survival and tumor response were not the primary end points of this study.

The present results suggest that escalated immunosuppression for toxic effects compromises ICI efficacy. Although a link with the use of second-line immunosuppressants seems likely, we cannot completely rule out the effects of protracted high-dose steroid treatment in the patients receiving second-line immunosuppressants. Indeed, early high dosage of steroids and prolonged steroid treatment have been correlated with worse survival.8,13 Unfortunately, data on steroid dosage and duration have not been registered in the DMTR. Of note, steroid titration was previously shown to commence earlier in patients receiving second-line anti-TNF, with numerically shorter steroid duration.26

More severe irAEs tend to occur earlier.30,31 Because ICIs are generally discontinued in case of severe irAEs,10,32 a shorter ICI exposure in patients with more severe irAEs could theoretically explain survival differences. However, in this study, no relevant difference in ICI treatment duration existed between patients with and without second-line immunosuppression. In the present cohort, second-line immunosuppression was highly associated with the type of toxic effect. In line with what was previously shown by Bai et al,13 we did not find a survival difference according to the type of irAE. Moreover, adjustment for the type of toxic effect in the multivariable analysis did not change the results.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, although we know the types of severe irAEs patients had, it was not registered which immunosuppressants were given for treatment of which irAE. Second, the lack of data on duration and dosage of immunosuppressants prohibits strong conclusions about a causal link between the use of second-line immunosuppressants and patient outcomes.

Conclusions

In this cohort study, data showed that survival was worse in patients with irAEs treated with escalated immunosuppression compared with those managed with only steroids. The current results suggest harmful effects of escalated immunosuppression rather than a specific anti–TNF-related effect.

A randomized clinical trial comparing treatment with infliximab vs the gut-specific vedolizumab in patients with ICI-induced colitis is currently being conducted33 but unfortunately is not powered on ICI-efficacy end points. With up to 40% of patients with advanced cancer currently being eligible for ICIs,34 the relevance of this research reaches beyond the melanoma field and urges more randomized studies, also in other tumor types.

eTable 1. Patient Characteristics stratified by management of toxicity in first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab advanced melanoma patients: steroids vs. steroids + anti-TNF vs. steroids + other second-line immunosuppressants excluding anti-TNF

eTable 2. Management strategies for grade ≥3 toxicity in patients treated with first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab (steroids + other second-line immunosuppressant group excluding anti-TNF)

eTable 3. Management strategies for grade ≥3 toxicity in patients treated with first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab excluded from the secondary analysis

eFigure 1. Progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) stratified by management of toxicity in first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab advanced melanoma patients: steroids vs. steroids + anti-TNF vs. steroids + other second-line immunosuppressants (excluding anti-TNF)

eFigure 2. Cox proportional hazard model of progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) stratified by management of toxicity in first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab advanced melanoma patients: steroids vs. steroids + anti-TNF + vs. steroids + other second-line immunosuppressants (excluding anti-TNF)

eFigure 3. Melanoma-specific survival stratified by management of toxicity in first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab advanced melanoma patients: steroids vs. steroids + any second-line immunosuppressant

eFigure 4. Melanoma-specific survival stratified by management of toxicity in first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab advanced melanoma patients: steroids vs. steroids + anti-TNF vs. steroids + other second-line immunosuppressants (excluding anti-TNF)

eTable 4. Reasons for discontinuation of ipilimumab-nivolumab stratified by management of toxicity in first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab advanced melanoma patients: steroids vs. steroids + any second-line immunosuppressant

eTable 5. Reasons for discontinuation of ipilimumab-nivolumab stratified by management of toxicity in first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab advanced melanoma patients: steroids vs. steroids + anti-TNF vs. steroids + other second-line immunosuppressants (excluding anti-TNF)

eFigure 5. Progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) stratified by type and management of toxicity in first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab advanced melanoma patients: steroids only vs. steroids + any second-line immunosuppressant vs. no grade 3 toxicity

References

- 1.van Zeijl MCT, Haanen JBAG, Wouters MWJM, et al. Real-world outcomes of first-line anti-PD-1 therapy for advanced melanoma: a nationwide population-based study. J Immunother. 2020;43(8):256-264. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Five-year survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(16):1535-1546. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Overall survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(14):1345-1356. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horvat TZ, Adel NG, Dang TO, et al. Immune-related adverse events, need for systemic immunosuppression, and effects on survival and time to treatment failure in patients with melanoma treated with ipilimumab at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(28):3193-3198. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.8448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weber JS, Hodi FS, Wolchok JD, et al. Safety profile of nivolumab monotherapy: a pooled analysis of patients with advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(7):785-792. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.66.1389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spain L, Diem S, Larkin J. Management of toxicities of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;44(February):51-60. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou X, Yao Z, Yang H, Liang N, Zhang X, Zhang F. Are immune-related adverse events associated with the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with cancer? a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):87. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01549-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eggermont AMM, Kicinski M, Blank CU, et al. Association between immune-related adverse events and recurrence-free survival among patients with stage III melanoma randomized to receive pembrolizumab or placebo: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(4):519-527. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.5570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verheijden RJ, May AM, Blank CU, et al. Association of anti-TNF with decreased survival in steroid refractory ipilimumab and anti-PD1-treated patients in the Dutch Melanoma Treatment Registry. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(9):2268-2274. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haanen JBAG, Carbonnel F, Robert C, et al. ; ESMO Guidelines Committee . Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl 4):iv119-iv142. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrelli F, Signorelli D, Ghidini M, et al. Association of steroids use with survival in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(3):1-13. doi: 10.3390/cancers12030546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, Yang M, Tao M, et al. Corticosteroid administration for cancer-related indications is an unfavorable prognostic factor in solid cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;99(July):108031. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2021.108031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bai X, Hu J, Betof Warner A, et al. Early use of high-dose-glucocorticoid for the management of irAE is associated with poorer survival in patients with advanced melanoma treated with anti-PD-1 monotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(21):5993-6000. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-1283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen AY, Wolchok JD, Bass AR. TNF in the era of immune checkpoint inhibitors: friend or foe? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2021;17(4):213-223. doi: 10.1038/s41584-021-00584-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suijkerbuijk KPM, Verheijden RJ. TNF inhibition for immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced irAEs: the jury is still out. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2021;17(8):505. doi: 10.1038/s41584-021-00640-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weber JS, Postow MA. TNFα blockade in checkpoint inhibition: the good, the bad, or the ugly? Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(9):2085-2086. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-0387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jochems A, Schouwenburg MG, Leeneman B, et al. Dutch Melanoma Treatment Registry: quality assurance in the care of patients with metastatic melanoma in the Netherlands. Eur J Cancer. 2017;72:156-165. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. ; for members of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Melanoma Expert Panel and the International Melanoma Database and Discovery Platform . Melanoma staging: evidence-based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(6):472-492. doi: 10.3322/caac.21409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228-247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schemper M, Smith TL. A note on quantifying follow-up in studies of failure time. Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(4):343-346. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(96)00075-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. The R Foundation . Accessed September 28, 2022. https://www.r-project.org

- 22.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. Springer Nature; 2000. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-3294-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kassambra A, Kosinski M, Biecek P, Fabian S. Drawing survival curves using ggplot2. survminer . Accessed September 28, 2022. https://rpkgs.datanovia.com/survminer/

- 24.Bass AR, Chen AY. Reply to: TNF inhibition for immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced irAEs: the jury is still out. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2021;17(8):505-506. doi: 10.1038/s41584-021-00641-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, Abu-Sbeih H, Mao E, et al. Immune-checkpoint inhibitor-induced diarrhea and colitis in patients with advanced malignancies: retrospective review at MD Anderson. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6(1):37. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0346-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson DH, Zobniw CM, Trinh VA, et al. Infliximab associated with faster symptom resolution compared with corticosteroids alone for the management of immune-related enterocolitis. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6(1):103. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0412-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lesage C, Longvert C, Prey S, et al. ; French Group of Onco-Dermatology . Incidence and clinical impact of anti-TNFα treatment of severe immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced colitis in advanced melanoma: the Mecolit Survey. J Immunother. 2019;42(5):175-179. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burdett N, Hsu K, Xiong L, et al. Cancer outcomes in patients requiring immunosuppression in addition to corticosteroids for immune-related adverse events after immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2020;16(2):e139-e145. doi: 10.1111/ajco.13177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zou F, Faleck D, Thomas A, et al. Efficacy and safety of vedolizumab and infliximab treatment for immune-mediated diarrhea and colitis in patients with cancer: a two-center observational study. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(11):e003277. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-003277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sznol M, Ferrucci PF, Hogg D, et al. Pooled analysis safety profile of nivolumab and ipilimumab combination therapy in patients with advanced melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(34):3815-3822. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.72.1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang DY, Salem JE, Cohen JV, et al. Fatal toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(12):1721-1728. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schneider BJ, Naidoo J, Santomasso BD, et al. Management of immune-related adverse events in patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: ASCO Guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(36):4073-4126. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Infliximab or vedolizumab in treating immune checkpoint inhibitor-related colitis in patients with genitourinary cancer or melanoma. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04407247. Updated June 24, 2022. Accessed October 2, 2022. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04407247?term=NCT04407247&draw=2&rank=1

- 34.Haslam A, Prasad V. Estimation of the percentage of us patients with cancer who are eligible for and respond to checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy drugs. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e192535. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Patient Characteristics stratified by management of toxicity in first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab advanced melanoma patients: steroids vs. steroids + anti-TNF vs. steroids + other second-line immunosuppressants excluding anti-TNF

eTable 2. Management strategies for grade ≥3 toxicity in patients treated with first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab (steroids + other second-line immunosuppressant group excluding anti-TNF)

eTable 3. Management strategies for grade ≥3 toxicity in patients treated with first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab excluded from the secondary analysis

eFigure 1. Progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) stratified by management of toxicity in first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab advanced melanoma patients: steroids vs. steroids + anti-TNF vs. steroids + other second-line immunosuppressants (excluding anti-TNF)

eFigure 2. Cox proportional hazard model of progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) stratified by management of toxicity in first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab advanced melanoma patients: steroids vs. steroids + anti-TNF + vs. steroids + other second-line immunosuppressants (excluding anti-TNF)

eFigure 3. Melanoma-specific survival stratified by management of toxicity in first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab advanced melanoma patients: steroids vs. steroids + any second-line immunosuppressant

eFigure 4. Melanoma-specific survival stratified by management of toxicity in first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab advanced melanoma patients: steroids vs. steroids + anti-TNF vs. steroids + other second-line immunosuppressants (excluding anti-TNF)

eTable 4. Reasons for discontinuation of ipilimumab-nivolumab stratified by management of toxicity in first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab advanced melanoma patients: steroids vs. steroids + any second-line immunosuppressant

eTable 5. Reasons for discontinuation of ipilimumab-nivolumab stratified by management of toxicity in first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab advanced melanoma patients: steroids vs. steroids + anti-TNF vs. steroids + other second-line immunosuppressants (excluding anti-TNF)

eFigure 5. Progression-free survival (A) and overall survival (B) stratified by type and management of toxicity in first-line ipilimumab-nivolumab advanced melanoma patients: steroids only vs. steroids + any second-line immunosuppressant vs. no grade 3 toxicity