Abstract

In vitro, lactoferrin (LF) strongly inhibits human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), which led us to hypothesize that in vivo HCMV might also be inhibited in secretions with high LF concentrations. In breast milk, high viral loads observed as high viral DNA titers tended to coincide with higher LF levels. However, the LF levels did not correlate to virus transmission to preterm infants. The viral load in the transmitting group was highest compared to the nontransmitting group. We conclude that viral load in breast milk is an important factor for transmission of the virus.

Breast-feeding is a strong risk factor for the postnatal transmission of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) (2, 21). The rate of transmission by consuming HCMV-infected breast milk ranges from 58 to 76% (3, 24).

Although HCMV-infected cells have been isolated from breast milk (1, 5) and cell-free virus has been detected in the whey of HCMV-infected mothers (1, 5), the mechanism of virus transmission through breast milk has not been elucidated yet. In contrast, HCMV is seldomly detected in colostrum (16). Breast milk has a protective effect against microbial infections and one of the protective components is lactoferrin (LF).

LF, an 80-kDa iron-binding glycoprotein, is present in the secondary vesicles of neutrophilic granulocytes (12). LF is also present in mucosal secretions (11, 13), where it is produced by epithelial cells, e.g., by the mammary glands during lactation (11, 13). At the mucosa, LF exerts its antibacterial and fungicidal effect (10, 11, 13). In vitro, LF exerts antiviral activities against a plethora of viruses, including hanta, HIV and HCMV (6, 15, 18, 22).

Lactoferrin concentrations are highest in colostrum and tend to decrease significantly within the first weeks of lactation (7, 14). We hypothesized that LF, among other defense proteins, would help to prevent the transmission HCMV to the newborn. In particular, for preterm newborns this nonspecific immunological defense could be important.

We set out to determine the LF concentrations in breast milk longitudinally to assess the relation between transmission of HCMV and LF levels in vivo. The relation between LF concentrations and the total amount of HCMV DNA in breast milk was studied in the same samples.

Study group.

Breast milk specimens were obtained from 23 breast-feeding mothers of preterm infants at the University Hospital of Tübingen. These mothers were enrolled prospectively between July 1995 and June 1998 in a clinical study of postnatal mother-to-preterm infant transmission of HCMV via breast milk (4). HCMV screening of seronegative and seropositive mother-infant pairs was performed by serology, virus culture, and PCR. Congenital and perinatal HCMV transmission were excluded. All mothers were informed of the aim of the study, which was approved by the ethical comittee of the University of Tübingen. All mothers were without clinical symptoms of HCMV invection and were classified into four groups. The first group were seronegative controls (group 1, n = 4), i.e., without transmission, DNA-lactia, and virolactia. Groups 2 (n = 4), 3 (n = 8), and 4 (n = 7) all comprised seropositive mothers with DNA-lactia. Transmission only occurred in group 4, for which the mothers, as in group 3, had virolactia. Group 2 mothers had no virolactia.

Milk whey preparation.

Native expressed breast milk was sampled longitudinally. Cell-free milk whey was prepared as described previously (5) and stored as aliquots at −20°C.

DNA extraction and qualitative nPCR from milk whey.

The extraction of DNA and detection of HCMV DNA by nested PCR (nPCR) in milk whey was performed as previously described (5). This approach allowed detection of 200 genome equivalents (GE) per ml of milk whey.

Determination of viral load by quantitative nPCR.

Extracted DNA from breast milk samples were added to PCR reaction mixtures containing 50 copies (high standard) or 10 copies (low standard) of a cloned CMV standard (9, 17). Target sequences were amplified with the external CMV-specific primers E1 and E2 (17). Then, 5 μl each of the external reaction was reamplified in a second round of PCR with the internal CMV-specific primers TGGE1B and TGGE2E. Standard and wild-type CMV PCR amplimers were quantitated by hybridization analysis as described elsewhere (17). For CMV DNA copies of ≥20 in 2.5 μl, the data from the high-standard reaction were used, and for CMV copies of <20, data from the low-standard reaction were used. Results were expressed as the number of CMV wild-type GE per ml of milk whey. Exact quantification was possible at between 400 to 200,000 GE/ml.

Detection of virolactia and transmission.

HCMV was cultured from milk whey by using human foreskin fibroblasts in the tube cell culture system. Virus transmission to the preterm infant was documented by positive viruria or DNA-uria not earlier than 3 weeks after delivery. Viruria was detected by virus culture; DNA-uria was detected by nPCR as outlined above.

Quantification of LF levels in breast milk.

LF concentrations in breast milk were determined as described elsewhere (23), with minor modifications. In brief, polyclonal antiserum against human LF (Jackson) was coated in 96-well plates (Hycult). Serial dilutions of breast milk were added to the wells. Human LF (Sigma) was used in the calibration curve. Bound antibody was detected with horseradish peroxidase-labeled antibodies (Jackson). Color was developed with TMB (trimethyl benzidine; Sigma), and the optical density (OD) at 450 nm was measured. These ODs were converted to LF concentrations using a four-parameter curve-fitting algorithm.

Statistical analyses.

The courses of LF concentrations in breast milk were calculated by using smoothing spline fits. Unpaired t tests were performed to investigate differences in HCMV DNA levels between the transmitting and nontransmitting groups.

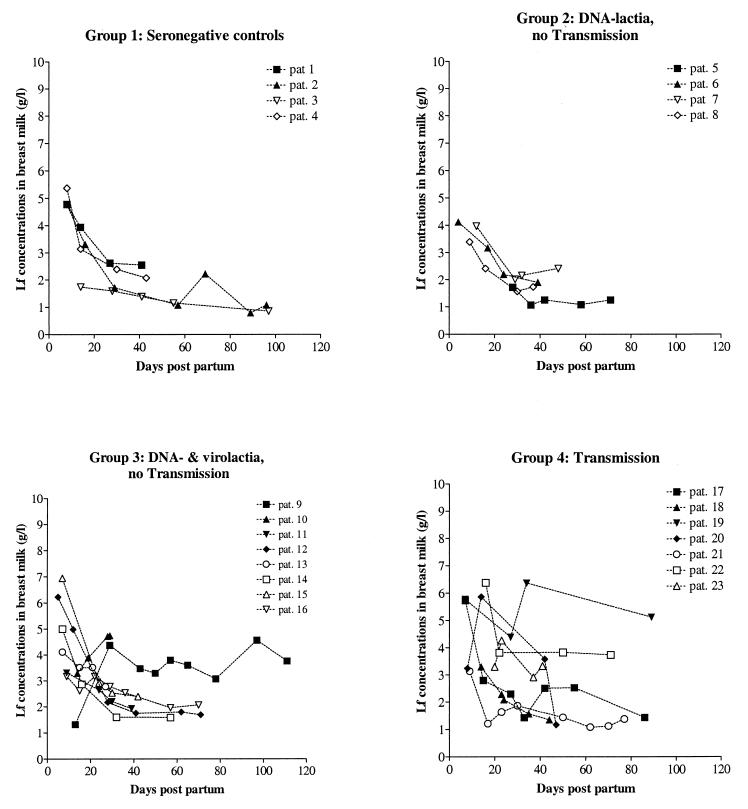

In the milk whey of breastfeeding mothers of preterm infants, LF concentrations were maximal in the colostrum, up to 7 mg/ml, and decreased approximately sevenfold in 2 weeks (Fig. 1). This finding is consistent with reported values found during term delivery (7, 14), although for four mothers an increase in LF levels was observed.

FIG. 1.

LF concentrations in breast milk decrease during lactation. Using smoothing spline fitting, no significant differences in decline or initial altitude of LF levels in mature milk were observed.

A significant difference in the initial breast milk LF concentrations or a decline in the LF concentrations during the course of lactation between the four different groups was not observed. The individual LF levels of the mothers in the transmission group tended to be more variable compared to the other groups (Fig. 1). According to the spline fits, these variations did not reach statistical significance. A significant correlation between LF concentrations and the amount HCMV DNA in breast milk was not observed (data not shown).

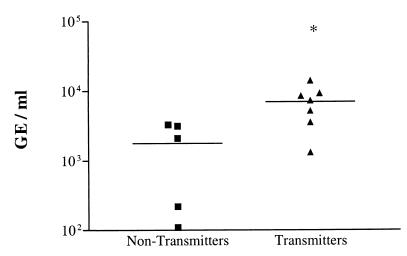

Viral loads in whey of HCMV-transmitting mothers (group 4) were significantly higher (P = 0.024) compared to nontransmitting mothers (groups 2 and 3; Fig. 2). Transmission of HCMV to newborns was observed only above a viral load of ca. 7 × 103 GE/ml. Thus, above this threshold not even high LF levels appear to protect from transmission. Indeed, we showed that the transmission of cell-bound virus in vitro could only be inhibited for 50% (8).

FIG. 2.

Quantification of viral DNA in milk whey of maternal HCMV transmitters (▴) and nontransmitters (■). The HCMV DNA load in milk whey of maternal transmitters is significantly increased compared to the nontransmitters. ∗, significantly different compared to the nontransmitters (unpaired t test, P = 0.024).

The reason for the more variable breast milk LF concentrations in the transmitter group could be reflected by different degrees of local inflammation in the breast (13). It is conceivable that, when large amounts of virus are present in breast milk, there also is viral replication in the breast, leading to a local inflammation reaction. As a result of this inflammation, the viral load in the transmission group (group 4) could have increased above a threshold level, which would lead to transmission and primary infection of the newborn. Although in vitro and in vivo data show that HCMV can replicate in several cell types (19, 20), the exact replication site in the mammary gland is not known.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially sponsored by the Program Co-ordination Committee for AIDS Research (PJS, PccAo grant no. 95011), The Netherlands; by Numico Research B. V., Wageningen, The Netherlands (B vd S); and by a research grant (DFG HA 1559 12-1; KH).

We thank K. Dietz (Institute of Medical Biometry, University of Tübingen) for assistance in the fitting of data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asanuma H, Numazaki K, Nagata N, Hotsubo T, Horino K, Chiba S. Role of milk whey in the transmission of human cytomegalovirus infection by breast milk. Microbiol Immunol. 1996;40:201–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1996.tb03335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diosi P, Babusceac L, Nevinglovschi O, Kun Stoicu G. Cytomegalovirus infection associated with pregnancy. Lancet. 1967;ii:1063–1066. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(67)90338-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dworsky M, Yow M, Stagno S, Pass R F, Alford C. Cytomegalovirus infection of breast milk and transmission in infancy. Pediatrics. 1983;72:295–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamprecht K, Maschmann J, Speer C P, Jahn G. Epidemiology of transmission of cytomegalovirus from mother to preterm infant by breastfeeding. Lancet. 2001;357:513–518. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamprecht K, Vochem M, Baumeister A, Boniek M, Speer C P, Jahn G. Detection of cytomegaloviral DNA in human milk cells and cell free milk whey by nested PCR. J Virol Methods. 1998;70:167–176. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(97)00179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harmsen M C, Swart P J, de Béthune M P, Pauwels R, De Clercq E, The T H, Meijer D K F. Antiviral effects of plasma and milk proteins: lactoferrin shows potent activity against both human immunodeficiency virus and human cytomegalovirus replication in vitro. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:380–388. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.2.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hennart P F, Brasseur D J, Delogne Desnoeck J B, Dramaix M M, Robyn C E. Lysozyme, lactoferrin, and secretory immunoglobulin A content in breast milk: influence of duration of lactation, nutrition status, prolactin status, and parity of mother. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;53:32–39. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/53.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kas-Deelen A M, The T H, Blom N, van der Strate B W A, de Maar E F, Van Son W J, Harmsen M C. Uptake of pp65 in in vitro generated pp65-positive polymorphonuclear cells mediated by phagocytosis and cell fusion? Intervirology. 2001;44:8–13. doi: 10.1159/000050024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuhn J E, Wendland T, Schafer P, Mohring K, Wieland U, Elgas M, Eggers H J. Monitoring of renal allograft recipients by quantitation of human cytomegalovirus genomes in peripheral blood leukocytes. J Med Virol. 1994;44:398–405. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890440416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuipers M E, de Vries-Hospers H G, Eikelboom M C, Meijer D K F, Swart P J. Synergistic fungistatic effects of lactoferrin in combination with antifungal drugs against clinical Candida isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2635–2641. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.11.2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levay P F, Viljoen M. Lactoferrin: a general review. Haematologica. 1995;80:252–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levy O. Antibiotic proteins of polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Eur J Haematol. 1996;56:263–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1996.tb00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lonnerdal B, Iyer S. Lactoferrin: molecular structure and biological function. Annu Rev Nutr. 1995;15:93–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.15.070195.000521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montagne P, Cuilliere M L, Mole C, Bene M C, Faure G. Microparticle-enhanced nephelometric immunoassay of lysozyme in milk and other human body fluids. Clin Chem. 1998;44:1610–1615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy M E, Kariwa H, Mizutani T, Yoshimatsu K, Arikawa J, Takashima I. In vitro antiviral activity of lactoferrin and ribavirin upon hantavirus. Arch Virol. 2000;145:1571–1582. doi: 10.1007/s007050070077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Numazaki K. Human cytomegalovirus infection of breast milk. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1997;18:91–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1997.tb01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schafer P, Braun R W, Mohring K, Henco K, Kang J, Wendland T, Kuhn J E. Quantitative determination of human cytomegalovirus target sequences in peripheral blood leukocytes by nested polymerase chain reaction and temperature gradient gel electrophoresis. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:2699–2707. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-12-2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimizu K, Matsuzawa H, Okada K, Tazume S, Dosako S, Kawasaki Y, Hashimoto K, Koga Y. Lactoferrin-mediated protection of the host from murine cytomegalovirus infection by a T-cell-dependent augmentation of natural killer cell activity. Arch Virol. 1996;141:1875–1889. doi: 10.1007/BF01718201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sinzger C, Jahn G. Human cytomegalovirus cell tropism and pathogenesis. Intervirology. 1996;39:302–319. doi: 10.1159/000150502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinzger C, Plachter B, Grefte A, The T H, Jahn G. Tissue macrophages are infected by human cytomegalovirus in vivo. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:240–245. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.1.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stagno S, Cloud G A. Working parents: the impact of day care and breast-feeding on cytomegalovirus infections in offspring. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2384–2389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swart P J, Kuipers M E, Smit C, Pauwels R, de Béthune M-P, De Clercq E, Huisman H, Meijer D K F. Antiviral effects of milk proteins: acylation results in polyanionic compounds with potent activity against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and 2 in vitro. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1996;12:769–775. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Strate B W A, Harmsen M C, The T H, Sprenger H G, De Vries H, Eikelboom M C, Kuipers M E, Meijer D K F, Swart P J. Plasma lactoferrin levels are decreased in end-stage AIDS patients. Viral Immunol. 2000;12:197–203. doi: 10.1089/vim.1999.12.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vochem M, Hamprecht K, Jahn G, Speer C P. Transmission of cytomegalovirus to preterm infants through breast milk. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:53–58. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199801000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]