Abstract

Seafood consumption has been identified as one of the major contributors of per- and poly(fluoroalkyl) substances (PFASs) to the human diet. To assess dietary exposure, highly consumed seafood products in the United States were selected for analysis. The analytical method previously used for processed food was extended to include four additional long-chain perflurocarboxylic acids (PFCAs), which have been reported in seafood samples. This method was single-lab-validated, and method detection limits were reported at 345 ng kg–1 for perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA) and 207 ng kg–1 for perfluoropentanoic acid (PFPeA) and below 100 ng kg–1 for the rest of the PFAS analytes. The 81 seafood samples (clams, crab, tuna, shrimp, tilapia, cod, salmon, pollock) were analyzed for 20 PFASs using the updated analytical method. Most of the seafood packaging was also analyzed by Fourier transform infrared-attenuated total reflectance (FTIR-ATR) to identify packaging potentially coated with PFASs. None of the packaging samples in this study were identified as having PFASs. A wide range of concentrations was observed among the seafood samples, ranging from below the method detection limit to the highest concentration of 23 μg kg–1 for the sum of PFASs in one of the canned clam samples. Such a wide range is consistent with those reported in previous studies. The highest concentrations were reported in clams and crabs, followed by cod, tuna, pollock, tilapia, salmon, and shrimp. Technical perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) dominated the profile of the clam samples, which has been consistently found in other clam samples, especially in Asia. Long-chain PFCAs, specifically perfluoroundecanoic (PFUdA) and perfluorododecanoic (PFDoA), were the most frequently detected analytes across all seafood samples. The trends observed are comparable with those in the literature where benthic organisms tend to have the highest PFAS concentrations, followed by lean fish, fatty fish, and aquaculture. The results from this study will be used to prioritize future studies and to inform steps to reduce consumer exposure to PFASs.

Keywords: PFAS, fish, shellfish, seafood, QuEChERS

Introduction

Per- and poly(fluoroalkyl) substances (PFASs) are a class of synthetic chemicals that have been used in a wide variety of industrial and consumer products, including textiles, carpets, paper coatings, aqueous film forming foam (AFFF), and in the metal plating industry.1 Their structures, which include multiple highly stable carbon–fluorine bonds, are resistant to degradation and have resulted in their persistence in the aquatic and terrestrial environment.2−4 Once in these environments, they can contaminate drinking water, livestock, seafood, and plants, resulting in dietary exposure. Other sources of human exposure to PFASs include air inhalation, dermal absorption, and the ingestion of dust.5−9

Fluorochemicals are also added to certain types of food packaging, typically paper and paperboard, as a grease-proofing agent. The potential of PFASs to migrate from food packaging to food is dependent on many factors, including the time and temperature of contact, the type of food, and the ability of the PFAS to overcome the resistance to migration at the packaging/food interface.10 Previous studies have suggested that the migration of fluoropolymer food contact materials is not a significant source of PFASs in food.10

In the scientific opinion released by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) in 2020, the most important contributor to dietary exposure in food was fish and other seafood for perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA).11 Other foods of importance were eggs, meats, fruits, vegetables, starchy roots and tubers, and drinking water.11 Seafood consumption has also been identified as an exposure pathway for PFASs in other studies.12−15 Relationships between the body burden of PFASs and seafood consumption have been reported in Japan,16 Norway,17−20 Germany,20 Poland,21 and France.22 In 2017, Christensen et al. examined PFAS levels in blood serum and found positive associations with certain PFASs and consumption of specific fish and shellfish types in the U.S. population.15

There have been few studies investigating PFASs in seafood purchased from U.S. markets. In 2010, Schecter et al. studied persistent organic pollutants in market basket samples, including seafood from Texas supermarkets.23 Seafood samples included salmon, canned tuna, fresh catfish fillet, tilapia, cod, canned sardines, and frozen fish sticks. Of these 7 types of fish, PFOA was the dominant PFAS detected in 6 different types, with concentrations less than 0.3 μg kg–1.23 PFBS and PFHxS were also detected in cod at 0.12 and 0.07 μg kg–1, respectively.23

Between 2010 and 2012, 46 retail samples were collected by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and analyzed for 10 PFASs.24 The 13 different types of fish included the top 10 most consumed fish and shellfish, according to the National Fisheries Institute. During this analysis, method detection limits were around 1 μg kg–1 or 1 part per billion (ppb). Out of the 46 samples, 11 had positive detects, with PFOS being the most commonly detected PFAS with the highest concentration in crab at 6.3 μg kg–1.24

In 2020, Ruffle et al. investigated 70 finfish and shellfish from U.S. grocery stores and fish markets, which were analyzed for 26 different PFASs.25 Out of 70 samples, 21 had positive detects with PFOS as the major PFAS identified. The detection limits ranged from 0.4 to 0.5 μg kg–1 and concentrations were typically single-digit or sub-ppb concentrations.25 An extensive literature search was also presented on PFASs in fish and shellfish in the United States, both from market basket surveys and freshwater fish and also from Europe, Asia, and Africa. Their findings suggested that PFAS exposure was low for consumers of market basket fish and shellfish; however, recreationally caught fish associated with known contaminated sites or point sources had higher tissue concentrations.25

The analysis of PFASs in foods obtained through FDA’s Total Diet Study began in 2018, with the first results reported in 2019.26 These results were from 91 composite food samples collected in the mid-Atlantic region, and there were two positive detects of PFOS in tilapia and in ground turkey at 0.087 and 0.086 μg kg–1, respectively.26 Further analysis of FDA’s Total Diet Study samples from other regions of the U.S. found positive detects in cod, fish sticks (pollock), shrimp, and canned tuna, along with protein powder with all concentrations less than 0.23 μg kg–1 of individual PFAS analytes.26−28 As a result of the primary detects in fish and shellfish, the FDA decided to undertake a targeted survey of the most commonly consumed seafood in the U.S. diet. The survey employed nonprobability sampling, specifically convenience sampling, to test PFASs in highly consumed seafood in interstate commerce.29 Since the U.S. imports more than 90% of its seafood supply30 and other countries have different regulations on the use of PFASs in industry and consumer products, it was important to identify the countries with the greatest imports for each seafood type for the targeted survey.

The objectives of this research were to extend the current analytical method to include four additional long-chain perfluorocarboxylic acids (PFCAs), since the dominant PFCAs detected in fish are perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), perfluoroundecanoic acid (PFUdA), and perfluorotridecanoic acid (PFTrDA),3 validate the method for three different types of seafood, and investigate PFAS analytes present in the most highly consumed seafood products available at retail. Additionally, most of the seafood packaging was investigated to assess the polymer composition and identify those that could contain PFASs.

Materials and Methods

Seafood Survey Design and Sample Collection

FDA used the National Fisheries Institute publication of the “Top 10 List for Seafood Consumption”,31 developed using annual landings and imports data from NOAA,30 to inform seafood products for collection. The survey targeted eight of the top 10 types of seafood consumed in the United States: shrimp, salmon, canned tuna, tilapia, pollock, cod, crab, and clams. Pangasius and catfish were also identified among the top 10 seafood products; however, these seafood types are regulated by the United States Department of Agriculture and were not included in this study. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 2015 to 2016 identified the same eight seafood types among those most consumed in the United States.32 The eight seafood types were further targeted based on (1) the prevalence of seafood that was wild-caught versus raised via aquaculture and (2) the top three countries that export the product to the U.S. (Table 1). To identify these attributes, internal FDA data sources on imports from fiscal year 2019 to 2020 were used.

Table 1. Eight Seafood Types Targeted for Collectiona.

| seafood type | U.S. per capita consumption | aquaculture vs wild-caught | country of origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| shrimp | 4.60 | aquaculture (73.8%) | India (40.9%) |

| Indonesia (18.2%) | |||

| Ecuador (15.9%) | |||

| salmon | 2.55 | aquaculture (85.9%) | Chile (36.6%) |

| Canada (35.1%) | |||

| Norway (9.3%) | |||

| canned tuna | 2.10 | wild-caught (100%) | Thailand (30.8%) |

| Ecuador (24.9%) | |||

| American Samoa (15.7%) | |||

| tilapia | 1.11 | aquaculture (87.5%) | China (28.8%) |

| Costa Rica (26.3%) | |||

| Colombia (20.1%) | |||

| pollock | 0.77 | wild-caught (100%) | China (34.6%) |

| Canada (24.1%) | |||

| United States (19.8%) | |||

| cod | 0.62 | wild-caught (100%) | Iceland (54.2%) |

| China (19.5%) | |||

| Canada (14.7%) | |||

| crab | 0.52 | wild-caught (99.9%) | Mexico (17.2%) |

| Indonesia (12.9%) | |||

| Canada (12.9%) | |||

| clam | 0.32 | wild-caught (85.9%) | Canada (54.1%) |

| Mexico (13.1%) | |||

| China (10.6%) |

The U.S. per capita consumption (lbs) was reported in the 2018 National Fisheries Institute top 10 list. The percentage of each seafood type that was wild-caught vs raised by aquaculture and the percentage of each seafood type for the top three contributing countries of origin were identified using internal FDA imports data from 2019 to 2020.

A convenience sampling approach was used to collect these targeted seafood samples at retail markets in the Washington, DC metropolitan area from May 2021 through March 2022. Certain clam samples were also purchased online. Per seafood type, 10 samples were collected, with the exception of crab, for which 11 samples were selected. The convenience sampling accommodated many of the targets; however, samples from the top three countries with the highest percentages of seafood products consumed in the United States could not be acquired in all cases. This could be the result of the limited DC metropolitan locations over which seafood products were surveyed, differences in seafood products available per geographic region, and/or broader diversity of countries of origin for a given seafood type.

Table S1 provides further descriptions of the seafood products collected at retail for PFAS analyses for the survey. This includes the item description, whether the sample was wild-caught or aquaculture, the country of origin, and other additional information. In accordance with regulations (7 USC 1621), the country of origin may represent the harvest location if the product has not been substantially transformed. However, in cases where substantial transformation of the seafood occurs (e.g., processing), the label shall indicate the country of origin on the label rather than the country in which the seafood was harvested. Four of the tuna samples were not labeled with the country of origin. It is likely that the products not labeled with origin were from the United States or a territory of the United States (e.g., American Samoa) as U.S. products are not required to indicate the United States as the country of origin.

Seafood Packaging

Fourier transform infrared-attenuated total reflectance (FTIR-ATR) is a spectroscopic tool that has been shown to be low-cost, rapid, and nondestructive. It can be used to probe packaging materials exclusively from its surface to approximately a 2 μm depth. If PFAS is incorporated into the food contact material (FCM), it is expected to be concentrated near the packaging surface to maximize its functional efficiency. FTIR-ATR was used to both identify the type of polymer that comprised the FCM and to compare to recently generated infrared spectra (IR) that were calculated using density functional theory (DFT) to potentially identify packaging coated with PFAS molecules.33 Out of 81 seafood samples, 56 packaging samples were analyzed using FTIR-ATR. The samples not analyzed (n = 25) were those where it was already determined they would not have PFASs due to their packaging materials, which do not typically have fluoropolymer coatings (tin cans and polypropylene containers). There also was one packing sample (cod 1–9) that could not be analyzed due to the packaging having been discarded. For FTIR-ATR analysis, a small strip of approximately 1 inch by 3 inches was cut from each package sample, placed under running hot water for a few seconds, and pat-dried with Kimwipe to rid of potential contaminants on the package surface. An additional ethanol wipe-down was required to remove residual traces of apparent fish oil on some packaging surfaces. Substrate-bound PFAS in packaging material is not expected to incur significant loss from this treatment. A Nicolet iS50 benchtop FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts) equipped with a single-bounce diamond ATR crystal was used to collect spectra for packaging samples at room temperature. To improve the signal-to-noise ratio, 128 scans were coadded at a nominal resolution of 4 cm–1. Thermo scientific Omnic software (version 9.11) controlled FTIR-ATR data acquisition in the spectral range between 4000 and 500 cm–1. Details of this approach are described elsewhere.34 Single-beam spectra of samples were collected and ratioed against an open beam (air) single-beam spectrum, which was collected beforehand. FTIR-ATR spectra of a blank as well as a polystyrene reference standard were collected before and after each daily run sequence to validate optical alignment and calibrate the spectrometer.

Solvents and Standards

The solvents used in this method (acetonitrile, methanol, water, formic acid) were Optima LC-MS grade from Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). The mobile phase additives ammonium acetate and 1-methylpiperidine were both purchased from Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Ammonium hydroxide, which was used during solid-phase extraction, was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA).

Native and isotopically labeled standards were purchased from Wellington Laboratories (Guelph, Ontario). The native analytes used were perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA); perfluoropentanoic acid (PFPeA); perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA); perfluoroheptanoic acid (PFHpA); technical mixture of perfluorooctanoic acid (T-PFOA); perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA); perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA); perfluoroundecanoic acid (PFUdA); perfluorododecanoic acid (PFDoA); perfluorotridecanoic acid (PFTrDA); perfluorotetradecanoic acid (PFTeDA); potassium perfluorobutanesulfonate (l-PFBS); sodium perfluoropentanesulfonate (l-PFPeS); sodium perfluorohexanesulfonate (l-PFHxS); sodium perfluoroheptanesulfonate (l-PFHpS); technical mixture of potassium perfluorooctanesulfonate (T-PFOS); 2,3,3,3-tetrafluoro-2-(1,1,2,2,3,3,3-heptafluoroproproxy)propanoic acid (HFPO-DA); sodium dodecafluoro-3H-4,8-dioxanonanoate (NaDONA); potassium 9-chlorohexadecafluoro-3-oxanonane-1-sulfoate (9Cl-PF3ONS); and potassium 11-chloroeicosafluoro-3-oxaudecane-1-sulfonate (11Cl-PF3OUdS). For PFOS and PFOA, concentration results were reported as the sum of linear and branched isomers, and for all other analytes, results are reported for the linear isomer only. Surrogate standards (SS) consisting of isotopically labeled standards were added to the food samples prior to extraction for isotope dilution mass spectrometry. These isotopically labeled surrogate standards were M3 PFBA, M3 PFPeA, MPFHxA, 13C PFOA, MPFUdA, MPFDoA, MPFTeDA, M3 PFBS, MPFHxS, 13C PFOS, and M3 HFPO. The internal standard (IS) added prior to injection was N-ethyl-d5-perfluoro-1-octane-solfonamidoacetic acid (d5-N-EtFOSAA).

The native neat standards all had PFAS concentrations of 50 μg mL–1. A 1000 ng mL–1 stock solution was made by adding 0.2 mL of each of the 20 PFAS natives to 6 mL of methanol for 10 mL total volume and was used for single-lab validation (SLV) spikes and for calibration curve preparation. Serial dilution of the 1000 ng mL–1 PFAS native stock solution to 100, 10, and 1 ng mL–1 solutions generated all stock solutions needed for the 7-point calibration curve (0.01–25 ng mL–1), the SLV spikes, as well as the method detection limit (MDL) spikes. The PFAS SS stock solution was generated by adding 0.2 mL of each of the 11 isotopically labeled internal standards (initial concentration 50 μg mL–1) to 7.8 mL of methanol for a final SS stock solution of 1 μg mL–1. The IS stock solution was prepared by adding 40 μL of 50 μg mL–1d5-N-EtFOSAA to 9.96 mL of methanol for a final IS stock solution of 0.2 μg mL–1.

Sample Extraction and Cleanup

The method used to detect PFASs in fish is similar to the previously published Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe (QuEChERS) method for PFASs in market foods.27 In short, fish samples were homogenized using an IKA tube mill (IKA Works, Inc., Wilmington, NC), and only the edible parts of the fish were homogenized (no skin, shells, or bones). In the case of canned seafood samples, the product was drained prior to homogenization. A 5 g sample of fish homogenate (wet weight) was weighed into a 50 mL polypropylene (PP) centrifuge tube. For method blanks, 5 mL of water was used in place of fish tissue. To each sample tube, 10 μL of 1 ng μL–1 SS was added (concentration of 1 ng mL–1 SS in the final extract). Spiked samples had 10 μL of 1 ng μL–1 native PFAS mix. Next, 5 mL of water, 10 mL of acetonitrile, and 150 μL formic acid were added to each sample. The samples were then vortexed for 1 min using a Glas-Col digital pulse mixer/vortexer (Terre Haute, IN) at 1500 rpm, with the pulse set to 70. A salt packet containing 6000 mg of MgSO4 and 1500 mg of NaCl (ECMSSFCS-MP, UCT, Bristol, PA) was then added to each sample. If the salt clumped, it was shaken vigorously until it became homogeneous and then vortexed for 30 s. Samples were then shaken for 5 min and then centrifuged for 5 min at room temperature at 10,000 rcf (Sorvall legend XTR centrifuge (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA)). After centrifugation, the supernatant was removed and added to a 15 mL centrifuge tube prefilled with dispersive solid-phase extraction (dSPE) containing 900 mg of MgSO4, 300 mg of PSA, and 150 mg of CGB (ECMPSCB15CT, UCT, Bristol, PA) and shaken to ensure all of the dSPE had dispersed in the sample. The 15 mL centrifuge tubes were then shaken for 5 min and centrifuged at 10,000 rcf for 5 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant was filtered using a 0.2 μm nylon filter into a clean 15 mL PP centrifuge tube. At this point, a 1 mL aliquot of the extract was removed for SPE cleanup; the remainder of the extract was stored at −20 °C pending further analysis.

A positive pressure manifold (PPM-48) was used for the cleanup of the fish samples (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) using WAX SPE cartridges (6 mL, 200 mg, 100 μm, Phenomenex Strata-XL-AW). The SPE cartridges were conditioned with 9 mL of 0.3% ammonium hydroxide in methanol, followed by 5 mL of water. The 1 mL aliquot of sample extract was diluted to 12 mL with water, and the diluted extract was then loaded on the column and allowed to pass through at a rate no faster than 2 drops per second. Once the sample passed through the SPE, the cartridge was washed with 5 mL of water and allowed to dry for ∼1 min. Then 4 mL of 0.3% ammonium hydroxide in methanol was loaded to elute the PFAS. The extract was blown to ∼1 mL using nitrogen in a 60 °C water bath (Turbovap LV, Biotage, Uppsala, Sweden), and additional methanol was added, if needed, to have a final volume of 1 mL. Internal standard (5 μL of 0.2 ng μL–1d5-N-EtFOSAA, totaling 1 ng) was added, and the sample was vortexed. A portion of the concentrated SPE eluent was then pipetted into a filter vial for LC-MS/MS analysis, and the unused portion was stored at −20 °C.

Samples that had detectable concentrations of PFOS were checked for cholic acid interferences. In instances where cholic acid interference was found, the original QuEChERS extract was cleaned using a previously described method for SPE (Supelclean ENVI-Carb, Millipore Sigma, St. Louis, MO)35 (Figures S1 and S2). Briefly, the ENVI-carb cartridge was preconditioned with 4 mL of methanol. Then, 3 mL from the QuEChERS extract was eluted through the cartridge. The eluent was then blown down to dryness and reconstituted with 3 mL of methanol. Internal standard was added (15 μL of 0.2 ng μL–1d5-N-EtFOSAA, totaling 1 ng) and vortexed. A portion was pipetted into a filter vial for LC-MS/MS analysis for PFOS; the remainder was stored at −20 °C.

Instrumental Analysis

Samples were analyzed on a Nexera X2 system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) liquid chromatography system. Analytes were separated using an XBridge BEH C18 (130 Å, 3.5 μm, 2.1 × 150 mm2) with an ACQUITY BEH C18 VanGuard pre-column (130 Å, 1.7 μm, 2.1 × 5 mm2) as the guard column (Waters, Milford, MA). The mobile phase consisted of 5 mM ammonium acetate and 5 mM 1-methylpiperidine (1-MP) in water (A) and methanol (B). The improvements observed with the use of 1-MP in the mobile phase were discussed in a previous publication.27 The solvent gradient was as follows: initially, 10% B held for 3 min, then %B increased from 10 to 40% between 3 and 3.1 min, from 3.1 to 26 min %B increased to 90%. The %B was then dropped to 10% from 26 to 26.1 min and held until 28 min. The column was held at a temperature of 40 °C, and the flow rate was 0.3 mL min–1. To prevent any PFAS contamination from being detected at the same retention times as the PFAS analytes, an XBridge BEH C18 (130 Å, 3.5 μm, 2.1 × 50 mm2) delay column was placed between the solvent mixer and the injector (Waters, Milford, MA). Based on previous PFAS studies with this instrumentation, the delay column kept any background PFAS outside of the scheduled multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) window of the PFAS analytes and would only be observed when the instrument is run in unscheduled mode.27 The MS/MS detector used was a Sciex 6500 plus QTRAP hybrid triple quadrupole/linear ion trap mass spectrometer with an electrospray ion source (ABSciex, Toronto, ON Canada). MRM monitoring was conducted for 20 analytes and 12 isotopically labeled standards, and their MRM transitions can be found in Table S2. An example chromatogram can be found in Figure S3. Any positive detects of PFBA and PFPeA had to be verified by a secondary analysis on the Q-Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer. This method was previously described,27 except for the source conditions, which were optimized in this study for PFBA and PFPeA. The ion spray voltage was −2.5 kV, capillary temperature was 350 °C, sheath gas was 35 au, auxiliary gas was 10 au, sweep gas was 0 au, auxillary heater temperature was 310 °C, and the S-Lens RF level was 25.

Results and Conclusions

Method Validation

The method for the determination of PFASs in fish and shellfish tissue was validated using the criteria presented in the “Guidelines for the Validation of Chemical Methods for the FDA Foods Program, 3rd edition.”36 Of the eight different fish and shellfish tissues analyzed in this method, three were chosen for validation: salmon, shrimp, and tuna. These tissues were chosen due to their range of fat content and amount of processing to adequately represent the eight different tissues analyzed. The three tissues were spiked at three concentrations (0.05, 0.5, and 2 μg kg–1 in food) in duplicate and processed with the method described herein. A successful validation required that all recoveries fall between 40 and 120% for the spikes at the method level of 1 μg kg–1.36 The recoveries are shown in Tables S3–S5 and all fall within the acceptable range. Along with the validation, the five other types of fish and shellfish analyzed also had duplicate spike (2 μg kg–1) recoveries processed to check method performance during the study (Table S6). The spike recoveries for all 20 analytes in all fish and shellfish tissues met the acceptability criteria discussed above, except for PFTrDA in cod; it should be noted that PFTrDA does not have a matched SS. Surrogate recoveries were also monitored for all samples analyzed to gain insight into extraction efficiency.

Method detection limits were determined using the procedure described in the Code of Federal Regulations (40 CFR 136, Appendix B, revision 2).37 Looking at the same tissues used for the validation (salmon, shrimp, tuna), nine replicates of each tissue were spiked at a low concentration (0.05 μg kg–1) and processed through the QuEChERS extraction and SPE cleanup. The method detection limit was determined by taking the variance of the response for the low concentration spikes and multiplying it by the Student t-value for a one-tail 99% confidence interval with the appropriate degrees of freedom, eight in this instance. The values were consistent across the three tissues, and the maximum value for the three was used for the MDL threshold for reporting purposes (Table S7). For PFBA and PFPeA, MDLs were also determined using 40 CFR 136 with the Q-Exactive Orbitrap mass spectrometer. The MDL for PFBA was reported as 345 ng kg–1 for PFBA and 207 ng kg–1 for PFPeA in shrimp samples. Besides PFBA and PFPeA, all other calculated MDL values were below 100 ng kg–1, which is at least a full order of magnitude lower than the MDLs (310–1280 ng kg–1) for the previous fish survey from 2013.24

Seafood Survey Results

Packaging

There are few studies on the infrared spectral data of PFAS molecules in the literature,33 and about 20 infrared spectra are openly available.38 Modeling has been employed to construct simulated infrared spectra of PFAS molecules and verified against measured spectra of corresponding molecules,33 and other researchers have determined the intrinsic carbon–fluorine vibration frequencies by introducing fluorine to nanodiamond to form carbon–fluorine bonds.39 The polymers identified by FTIR for each seafood packaging for shrimp, tilapia, salmon, pollock, and cod are given in Table S1. There was only one sample, a coated paper wrapper for salmon 1–9, that showed potential for being coated with PFASs. Additional IR bands that are not present in the cellulose spectra (1535, 1648, 2849, and 2913 cm–1) were observed along with a rather broad absorption band near the 1230 cm–1 region. After further investigation using a food oil (miglyol) to observe beading (indicative of the presence of PFAS) or wetting of the surface (indicative of non-PFAS) and extraction with methanol and analysis by LC-MS/MS, it was confirmed that the coating was not PFAS but some other type of wax. As a result, it appears that the packaging did not contribute to any PFAS concentrations observed in seafood in this study.

Clams

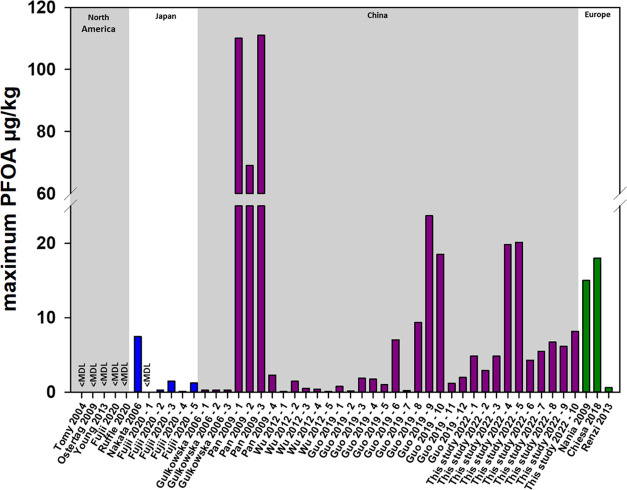

The results of the seafood survey are presented in Figure 1, and raw data can be found in Tables S7–S14. The clam data, which represents 10 individual canned clam samples, had the highest total PFAS concentrations of all seafood types. The sum of PFASs ranged from 4 to 23 μg kg–1, with PFOA as the dominant PFAS (ranged from 3 to 20 μg kg–1) with smaller contributions from the long-chain PFCAs. These samples were all labeled as products of China, and previous studies have also found high PFAS concentrations in clams from the Bohai Sea (up to 111 μg kg–1 PFOA), which has known fluoropolymer manufacturing in the region.40,41 Other studies in a tropic food web in a lake in Italy found that mussels and clams had the highest PFOA concentrations of all seafood types tested, indicating that feed and detritus feeding species had the greatest exposure from the human-stressed water ecosystem.42 Fujii et al. found clams with the greatest PFAS exposure were close to populated and industrial areas compared to less populated areas and the open sea; thus, they are directly affected by their habitats and reflect contamination from their local environment.43 A summary of maximum PFOA concentrations detected in clams from different locations based on a literature search is presented in Figure 2. The limited data available from North America included locations in Nunavat (n = 1) and Vancouver, Canada (n = 9), both of which had no detections of PFOA.43,44 In Japan, there were also few studies with detectable concentrations, where the highest (7.5 μg kg–1) was from a tidal flat in the Tojin River estuary.45 PFAS, in clams purchased at markets in China from six provinces that border the Bohai Sea, Yellow sea, East China Sea, and South China Sea (<1.5 ng kg–1 PFOA)46 and at two markets in Zhoushan and Guangzhou (<0.27 ng kg–1 PFOA)47 had lower concentrations compared to those collected directly from the Bohai Sea (Figure 2).40,41 A limited number of samples have been collected in Europe from the Mediterannean,48 an Orbetello coastal lagoon in Italy,42 and Milan, Italy.49 More data on clams harvested in North America and imported to the U.S. would provide information to gain a better assessment of concentrations in clams commonly consumed in the U.S.

Figure 1.

PFAS concentrations in samples from the FDA 2021–2022 seafood survey (μg kg–1). The y-axis for clams has a maximum of 25 μg kg–1, while all of the other y-axes are the same, with a maximum at 2.5 μg kg–1.

Figure 2.

Maximum PFOA concentrations in clams reported in the literature by region.

Crabs

Crabs had the second-highest sum of PFAS concentrations from the survey (Figure 1). The majority (9 out of 11) samples came from Indonesia, with two from Mexico (crab 6 and 8). The samples from Mexico had lower concentrations (0.16–0.37 μg kg–1) compared to the Indonesian crabs (0.6–2.2 μg kg–1). The distribution of PFASs in crabs was different from the clams in that there was no dominant PFAS, and long-chain PFCAs (C8–C14) made up 84–100% of total PFASs measured, except for crab 11, in which long-chain PFCAs made up 40%. In the clams, the technical PFOA mixture was observed, while in the crabs, only the linear isomer of PFOA was detected in all samples. Crabs purchased at markets in China had primarily PFOS detects (0.9–4.6 μg kg–1) compared to PFOA (0.34–1.6 μg kg–1).47 Crabs caught off the coast of the Netherlands in 2019 had a higher sum of PFASs in crab meat (8.2 μg kg–1) when looking at the same seven analytes as those in this study.50 Noorlander et al. found the highest PFAS concentrations in shellfish (mussels, shrimp, crab) compared to fish, beef, butter, eggs, pork, and milk.51 The highest concentrations (0.83 μg kg–1 PFOS and 0.58 μg kg–1 PFOA) were similar to those in this study (0.38 μg kg–1 PFOS and 0.51 μg kg–1 PFOA) for crab samples. The concentrations of PFASs in crabs purchased from U.S. markets24,25 appear to have decreased across all analytes from 201324 compared to those in 202025 and in this study. Although there are more analyte detections in the current study, this is largely due to the lower detection limits that are available now due to improvements in methods and instrumentation.

Cod

In this study, the sum of PFASs in cod ranged from less than the MDL to 0.96 μg kg–1. The PFASs detected included the long-chain PFCAs and PFOS, with the largest contributions from PFUdA and PFDoA. In 2009, cod purchased from supermarkets in Dallas, TX, had concentrations of PFOA (0.1 μg kg–1) similar to those found in this study (0.105 and 0.102 μg kg–1).23 Similar concentration ranges were also observed in cod fillets from the Arctic,52−54 and PFUdA (0.1 μg kg–1) was the dominant PFAS detected in samples from the Svalbard region.52

Salmon

PFDoA was the only analyte detected above the MDL in all of the salmon samples. The concentrations were all less than 0.045 μg kg–1. All of these samples were Atlantic salmon from aquaculture and consisted of fresh (5), frozen (4), and smoked (1) salmon. This was also the only fatty fish analyzed in this study. van Leeuwen et al. also reported no detects of PFASs in farmed salmon from the Netherlands,55 while salmon purchased in Texas in 2009 had a PFOA concentration of 0.07 μg kg–1.23 It is unclear whether this salmon was farmed or not. In 2020, Ruffle et al. examined three types of salmon from Alaska, one from China, and two farmed samples from Norway and Canada.25 None of these samples had detects above the MDL.25

Pollock

Of the 10 pollock samples tested, eight were breaded fillets or fish sticks, one was a salted fish, and one was a wild-caught fillet. The sum of total PFASs ranged from not detected to 0.73 μg kg–1. Only long-chain PFCAs were detected (PFNA, PFDA, PFUdA, PFDoA, PFTrDA). In previous FDA studies, no PFAS was detected above the MDL in pollock in 2013, and PFOS and PFNA were detected in fish sticks as part of the Total Diet Study samples at a concentration of 0.045 μg kg–1 and at 0.05 μg kg–1, respectively.24,26 Schecter et al. detected PFOA at 0.2 μg kg–1 purchased from a U.S. supermarket in 2009.23

Tuna

The tuna samples in this study were primarily canned with one pouch sample, and the primary country of origin was Thailand (n = 5), with one sample from Ecuador and four samples where the origin was unknown. All samples were wild-caught, and the sum of PFASs ranged from 0.083 to 1.75 μg kg–1. Nine out of 10 samples had a sum of PFASs below 0.35 μg kg–1, while one sample had a sum of 1.75 μg kg–1. PFUdA and PFDoA were detected in all samples. Previous U.S. studies found no PFAS concentrations above the detection limits,23,24 and recently, 0.076 μg kg–1 PFOS was found in samples from FDA’s Total Diet Study.27

Tilapia

Of all lean fish sampled in this study, tilapia had the lowest concentrations, with the sum of PFASs ranging from not detected to 0.09 μg kg–1, with two PFOS detections at 0.065 and 0.05 μg kg–1. These detections are similar to those previously measured by the FDA through Total Diet Study samples (0.087 and 0.083 μg kg–1 PFOS).26,56 Ruffle et al. did not detect any PFASs above their MDL (∼0.5 ng mL–1) in four samples, in which three were farmed, and one was wild-caught.25 Out of the 10 samples analyzed in this study, nine were labeled as aquaculture, and one was unknown. Studies of PFAS in farmed fish in China found the lowest mean levels of PFOS in tilapia (0.26–1.6 μg kg–1) and higher concentrations in crucian carp, grass carp, bighead, and snakehead.57 Wild-caught tilapia from South Africa in a watershed thought to be contaminated found the lowest PFAS concentrations in the muscle (average of 1 μg kg–1), with increasing concentrations in adipose tissue, spleen, kidney, and the highest in the liver (average of 11 μg kg–1).58

Shrimp

Shrimp had the lowest PFAS concentrations of all types of seafood tested and had only one detect of 0.027 μg kg–1 of PFDoA in all 10 samples. These samples were primarily from Indonesia, with three from India and one that was from an unknown location; all were harvested from aquaculture. Other studies have found higher concentrations of PFASs in shrimp from locations such as China (PFOS = 13.9 μg kg–1),47 Greenland (mean PFOS = 0.35 μg kg–1)54 supermarkets in the Netherlands (up to 0.5 μg kg–1 PFOS and other long-chain PFCAs),55 and in previous studies from the U.S. (up to 4.8 μg kg–1 PFOS, 2.4 μg kg–1 PFUdA, 1.2 μg kg–1 PFDA, and 1.2 μg kg–1 PFNA).24 Typically, shrimp, mollusks, and crabs have some of the highest PFAS concentrations due to the ability of benthic invertebrates to uptake sediment, which could be contaminated by the sorption of neutral or acidic PFAS.59 The lack of PFAS detections in this study is likely due to the shrimp being harvested from aquaculture.

Implications

The primary exposure of PFASs to fish and shellfish is from water uptake through the gills and filter-feeding for bivalves and crustacean.41 These organisms can uptake PFASs from the aquatic environment through water, suspended solids, and sediment.41 Biomagnification was not observed during uptake studies of PFCAs to rainbow trout;60 however, biomagnification of PFOS has been observed in fish in Japan.61 It has been shown that PFSAs more readily bioaccumulate than PFCAs in fish and that carbon chain lengths with less than 7 fluorinated carbons are not bioaccumulative.62 Based on results from a tropical estuary, fish had lower concentrations of PFCAs than crustaceans and bivalves, which could be attributed to different exposure routes or accumulation in fish.63 In the Netherlands, the highest concentrations were observed in shellfish (mussels, crab, and shrimp), followed by lean fish (cod, plaice, pollock, tuna) and then fatty fish (salmon, mackerel, eel, and herring), and lower concentrations were found in other food types such as beef, butter, eggs, and cheese.51 Further studies in the Netherlands found PFAS levels were highest in eel, followed by bivalves and crustaceans, marine fish, and farmed fish.50 In this study, the same trends are observed, with the highest concentrations in shellfish (clams, crabs), followed by lean fish (cod, pollock, tuna, tilapia), and fatty fish (salmon) having the lowest concentrations of all of the finfish. In this study, however, shrimp had only one compound detected in all 10 samples, likely because these samples were produced via aquaculture, which would follow the same observations as reported in the Netherlands.50

Overall, PFAS concentrations measured in this study were consistent with those that have been previously reported in the literature. The results from this study will be used to prioritize future studies and to inform steps to reduce consumer exposure to PFASs. The extension and validation of the analytical method to include four additional analytes which are of interest in seafood samples will allow for continued and improved monitoring of the U.S. food supply.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Brian Ng for his contribution to calculating MDLs for the HR-MS instrument and Dr. Cynthia Srigley for helping them complete the seafood analysis.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jafc.2c04673.

List of all seafood samples collected for the FDA 2021–22 seafood survey; single-lab validation and QC spike recoveries; sample data; and chromatograms of a spiked tuna sample and of cod sample before and after cholic acid interference cleanup (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Kissa E.Fluorinated Surfactants and Repellents, 2nd ed.; Marcel Dekker: New York, 2001; Vol. 97. [Google Scholar]

- Buck R. C.; Franklin J.; Berger U.; Conder J. M.; Cousins I. T.; de Voogt P.; Jensen A. A.; Kannan K.; Mabury S. A.; van Leeuwen S. P. J. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment: terminology, classification, and origins. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manage. 2011, 7, 513–541. 10.1002/ieam.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens L.; Bundschuh M. Fate and effects of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances in the aquatic environment: A review. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2014, 33, 1921–1929. 10.1002/etc.2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giesy J. P.; Kannan K. Global distribution of perfluorooctane sulfonate in wildlife. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2001, 35, 1339–1342. 10.1021/es001834k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Silva A. O.; Allard C. N.; Spencer C.; Webster G. M.; Shoeib M. Phosphorus-Containing Fluorinated Organics: Polyfluoroalkyl Phosphoric Acid Diesters (diPAPs), Perfluorophosphonates (PFPAs), and Perfluorophosphinates (PFPIAs) in Residential Indoor Dust. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 12575–12582. 10.1021/es303172p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipovic M.; Berger U. Are perfluoroalkyl acids in waste water treatment plant effluents the result of primary emissions from the technosphere or of environmental recirculation?. Chemosphere 2015, 129, 74–80. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.07.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strynar M. J.; Lindstrom A. B. Perfluorinated Compounds in House Dust from Ohio and North Carolina, USA. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 3751–3756. 10.1021/es7032058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebbink W. A.; Berger U.; Cousins I. T. Estimating human exposure to PFOS isomers and PFCA homologues: The relative importance of direct and indirect (precursor) exposure. Environ. Int. 2015, 74, 160–169. 10.1016/j.envint.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoeib M.; Harner T.; Webster G. M.; Lee S. C. Indoor Sources of Poly- and Perfluorinated Compounds (PFCs) in Vancouver, Canada: Implications for Human Exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 7999–8005. 10.1021/es103562v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begley T. H.; White K.; Honigfort P.; Twaroski M. L.; Neches R.; Walker R. A. Perfluorochemicals: Potential sources of and migration from food packaging. Food Addit. Contam. 2005, 22, 1023–1031. 10.1080/02652030500183474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrenk D.; Bignami M.; Bodin L.; Chipman J. K.; del Mazo J.; Grasl-Kraupp B.; Hogstrand C.; Hoogenboom L.; Leblanc J.-C.; Nebbia C. S.; Nielsen E.; Ntzani E.; Petersen A.; Sand S.; Vleminckx C.; Wallace H.; Barregård L.; Ceccatelli S.; Cravedi J.-P.; Halldorsson T. I.; Haug L. S.; Johansson N.; Knutsen H. K.; Rose M.; Roudot A.-C.; Van Loveren H.; Vollmer G.; Mackay K.; Riolo F.; Schwerdtle T.; Risk to human health related to the presence of perfluoroalkyl substances in food. EFSA J. 2020, 18, e06223 10.2903/j.efsa.2020.6223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tittlemier S. A.; Pepper K.; Seymour C.; Moisey J.; Bronson R.; Cao X. L.; Dabeka R. W. Dietary exposure of Canadians to perfluorinated carboxylates and perfluorooctane sulfonate via consumption of meat, fish, fast foods, and food items prepared in their packaging. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 3203–3210. 10.1021/jf0634045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger U.; Glynn A.; Holmström K. E.; Berglund M.; Ankarberg E. H.; Törnkvist A. Fish consumption as a source of human exposure to perfluorinated alkyl substances in Sweden - analysis of edible fish from Lake Vättern and the Baltic Sea. Chemosphere 2009, 76, 799–804. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewurtz S. B.; Bhavsar S. P.; Petro S.; Mahon C. G.; Zhao X. M.; Morse D.; Reiner E. J.; Tittlemier S. A.; Braekevelt E.; Drouillard K. High levels of perfluoroalkyl acids in sport fish species downstream of a firefighting training facility at Hamilton International Airport, Ontario, Canada. Environ. Int. 2014, 67, 1–11. 10.1016/j.envint.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen K. Y.; Raymond M.; Blackowicz M.; Liu Y.; Thompson B. A.; Anderson H. A.; Turyk M. Perfluoroalkyl substances and fish consumption. Environ. Res. 2017, 154, 145–151. 10.1016/j.envres.2016.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi M.; Arisawa K.; Uemura H.; Katsuura-Kamano S.; Takami H.; Sawachika F.; Nakamoto M.; Juta T.; Toda E.; Mori K.; Hasegawa M.; Tanto M.; Shima M.; Sumiyoshi Y.; Kodama K.; Suzuki T.; Nagai M.; Satoh H. Consumption of Seafood, Serum Liver Enzymes, and Blood Levels of PFOS and PFOA in the Japanese Population. J. Occup. Health 2013, 55, 184–194. 10.1539/joh.12-0264-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rylander C.; Sandanger T. M.; Frøyland L.; Lund E. Dietary Patterns and Plasma Concentrations of Perfluorinated Compounds in 315 Norwegian Women: The NOWAC Postgenome Study. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 5225–5232. 10.1021/es100224q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haug L. S.; Thomsen C.; Brantsæter A. L.; Kvalem H. E.; Haugen M.; Becher G.; Alexander J.; Meltzer H. M.; Knutsen H. K. Diet and particularly seafood are major sources of perfluorinated compounds in humans. Environ. Int. 2010, 36, 772–778. 10.1016/j.envint.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen S.; Vestergren R.; Herzke D.; Melhus M.; Evenset A.; Hanssen L.; Brustad M.; Sandanger T. M. Exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances through the consumption of fish from lakes affected by aqueous film-forming foam emissions — A combined epidemiological and exposure modeling approach. The SAMINOR 2 Clinical Study. Environ. Int. 2016, 94, 272–282. 10.1016/j.envint.2016.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölzer J.; Göen T.; Just P.; Reupert R.; Rauchfuss K.; Kraft M.; Müller J.; Wilhelm M. Perfluorinated Compounds in Fish and Blood of Anglers at Lake Möhne, Sauerland Area, Germany. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 8046–8052. 10.1021/es104391z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falandysz J.; Taniyasu S.; Gulkowska A.; Yamashita N.; Schulte-Oehlmann U. Is Fish a Major Source of Fluorinated Surfactants and Repellents in Humans Living on the Baltic Coast?. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 748–751. 10.1021/es051799n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denys S.; Fraize-Frontier S.; Moussa O.; Bizec B. L.; Veyrand B.; Volatier J.-L. Is the fresh water fish consumption a significant determinant of the internal exposure to perfluoroalkylated substances (PFAS)?. Toxicol. Lett. 2014, 231, 233–238. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schecter A.; Colacino J.; Haffner D.; Patel K.; Opel M.; Päpke O.; Birnbaum L. Perfluorinated compounds, polychlorinated biphenyls, and organochlorine pesticide contamination in composite food samples from Dallas, Texas, USA. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, 796–802. 10.1289/ehp.0901347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young W. M.; South P.; Begley T. H.; Noonan G. O. Determination of Perfluorochemicals in Fish and Shellfish Using Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 11166–11172. 10.1021/jf403935g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruffle B.; Vedagiri U.; Bogdan D.; Maier M.; Schwach C.; Murphy-Hagan C. Perfluoroalkyl Substances in U.S. market basket fish and shellfish. Environ. Res. 2020, 190, 109932 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genualdi S.; Young W.; DeJager L.; Begley T. Method Development and Validation of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in Foods from FDA’s Total Diet Study Program. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 5599–5606. 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c01777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genualdi S.; Beekman J.; Carlos K.; Fisher C. M.; Young W.; DeJager L.; Begley T. Analysis of per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in processed foods from FDA’s Total Diet Study. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2022, 414, 1189–1199. 10.1007/s00216-021-03610-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) , https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/foss/f?p=215:200:4422702076538:Mail:NO:::.

- Williamson K.Populations and Samples. In Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Williamson K.; Johanson G., Eds.; Chandos Publishing, 2018; Chapter 15, pp 359–377. [Google Scholar]

- Fisheries of the United States, U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA Current Fishery Statistics No. 2018. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/feature-story/fisheries-united-states-2018 (accessed Feb 25, 2022).

- (NFI), N. F. I. National Fisheries Institute (NFI), U.S. Per-Capita Consumption by Species in Pounds. https://www.aboutseafood.com/about/top-ten-list-for-seafood-consumption/ (accessed Feb 25, 2022).

- National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Questionnaire Data. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/search/datapage.aspx?Component=Questionnaire&CycleBeginYear=2015 (accessed March 22, 2022).

- Wallace S.; Lambrakos S. G.; Shabaev A.; Massa L. On using DFT to construct an IR spectrum database for PFAS molecules. Struct. Chem. 2022, 33, 247–256. 10.1007/s11224-021-01844-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Limm W.; Karunathilaka S. R.; Yakes B. J.; Mossoba M. M. A portable mid-infrared spectrometer and a non-targeted chemometric approach for the rapid screening of economically motivated adulteration of milk powder. Int. Dairy J. 2018, 85, 177–183. 10.1016/j.idairyj.2018.06.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strynar M. J.; Delinsky A. D.; Lindstrom A. B.; Nakayama S. F.; Reiner E. J.. LC/TOFMS and UPLC-MS/MS Methods for the Analysis of Perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) and the Reduction of Matrix Interference in Complex Biological Matrices ASMS Poster Presentation 2009.

- Guidelines for the Validation of Chemical Methods for the FDA FVM Program. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Science/research/FieldScience/UCM273418.pdf (accessed March 23, 2017).

- 40 CFR part 136, Appendix B: Definition and Procedure for the Determination of the Method Detection limit, Revision 2, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Washington, DC. 2016.

- U.S. Secretary of Commerce on behalf of the U.S.A., IR Spectrum from NIST Standard Reference Database 69: NIST Chemistry Webbook. 2017.

- Osipov V. Y.; Romanov N.; Kogane K.; Touhara H.; Hattori Y.; Takai K. Intrinsic infrared absorption for carbon–fluorine bonding in fluorinated nanodiamond. Mendeleev Commun. 2020, 30, 84–87. 10.1016/j.mencom.2020.01.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M.; Zheng G.; Peng J.; Meng D.; Wu H.; Tan Z.; Li F.; Zhai Y. Distribution of perfluorinated alkyl substances in marine shellfish along the Chinese Bohai Sea coast. J. Environ. Sci. Health, Part A 2019, 54, 271–280. 10.1080/03601234.2018.1559570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y.; Shi Y.; Wang Y.; Cai Y.; Jiang G. Investigation of perfluorinated compounds (PFCs) in mollusks from coastal waters in the Bohai Sea of China. J. Environ. Monit. 2010, 12, 508–513. 10.1039/B909302H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renzi M.; Guerranti C.; Giovani A.; Perra G.; Focardi S. E. Perfluorinated compounds: levels, trophic web enrichments and human dietary intakes in transitional water ecosystems. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2013, 76, 146–157. 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii Y.; Harada K. H.; Nakamura T.; Kato Y.; Ohta C.; Koga N.; Kimura O.; Endo T.; Koizumi A.; Haraguchi K. Perfluorinated carboxylic acids in edible clams: A possible exposure source of perfluorooctanoic acid for Japanese population. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263, 114369 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ostertag S. K.; Tague B. A.; Humphries M. M.; Tittlemier S. A.; Chan H. M. Estimated dietary exposure to fluorinated compounds from traditional foods among Inuit in Nunavut, Canada. Chemosphere 2009, 75, 1165–1172. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata H.; Kannan K.; Nasu T.; Cho H. S.; Sinclair E.; Takemurai A. Perfluorinated contaminants in sediments and aquatic organisms collected from shallow water and tidal flat areas of the Ariake Sea, Japan: environmental fate of perfluorooctane sulfonate in aquatic ecosystems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 4916–4921. 10.1021/es0603195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.; Wang Y.; Li J.; Zhao Y.; Guo F.; Liu J.; Cai Z. Perfluorinated compounds in seafood from coastal areas in China. Environ. Int. 2012, 42, 67–71. 10.1016/j.envint.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulkowska A.; Jiang Q.; So M. K.; Taniyasu S.; Lam P. K. S.; Yamashita N. Persistent Perfluorinated Acids in Seafood Collected from Two Cities of China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 3736–3741. 10.1021/es060286t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nania V.; Pellegrini G. E.; Fabrizi L.; Sesta G.; Sanctis P. D.; Lucchetti D.; Pasquale M. D.; Coni E. Monitoring of perfluorinated compounds in edible fish from the Mediterranean Sea. Food Chem. 2009, 115, 951–957. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.01.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa L. M.; Nobile M.; Malandra R.; Pessina D.; Panseri S.; Labella G. F.; Arioli F. Food safety traits of mussels and clams: distribution of PCBs, PBDEs, OCPs, PAHs and PFASs in sample from different areas using HRMS-Orbitrap and modified QuEChERS extraction followed by GC-MS/MS. Food Addit. Contam., Part A 2018, 35, 959–971. 10.1080/19440049.2018.1434900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafeiraki E.; Gebbink W. A.; Hoogenboom R. L. A. P.; Kotterman M.; Kwadijk C.; Dassenakis E.; van Leeuwen S. P. J. Occurrence of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in a large number of wild and farmed aquatic animals collected in the Netherlands. Chemosphere 2019, 232, 415–423. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.05.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noorlander C. W.; van Leeuwen S. P. J.; te Biesebeek J. D.; Mengelers M. J. B.; Zeilmaker M. J. Levels of Perfluorinated Compounds in Food and Dietary Intake of PFOS and PFOA in The Netherlands. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 7496–7505. 10.1021/jf104943p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk J.; Flor M.; Karl H.; Lahrssen-Wiederholt M. Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in beaked redfish (Sebastes mentella) and cod (Gadus morhua) from arctic fishing grounds of Svalbard. Food Addit. Contam., Part B 2020, 13, 34–44. 10.1080/19393210.2019.1690052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powley C. R.; George S. W.; Russell M. H.; Hoke R. A.; Buck R. C. Polyfluorinated chemicals in a spatially and temporally integrated food web in the Western Arctic. Chemosphere 2008, 70, 664–672. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomy G. T.; Budakowski W.; Halldorson T.; Helm P. A.; Stern G. A.; Friesen K.; Pepper K.; Tittlemier S. A.; Fisk A. T. Fluorinated Organic Compounds in an Eastern Arctic Marine Food Web. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 6475–6481. 10.1021/es049620g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen S. P. J.; van Velzen M. J. M.; Swart C. P.; van der Veen I.; Traag W. A.; de Boer J. Halogenated Contaminants in Farmed Salmon, Trout, Tilapia, Pangasius, and Shrimp. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 4009–4015. 10.1021/es803558r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Total Diet Study. https://www.fda.gov/food/science-research-food/total-diet-study (accessed Sept 8, 2018).

- Shi Y.; Wang J.; Pan Y.; Cai Y. Tissue distribution of perfluorinated compounds in farmed freshwater fish and human exposure by consumption. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2012, 31, 717–723. 10.1002/etc.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangma J. T.; Reiner J. L.; Botha H.; Cantu T. M.; Gouws M. A.; Guillette M. P.; Koelmel J. P.; Luus-Powell W. J.; Myburgh J.; Rynders O.; Sara J. R.; Smit W. J.; Bowden J. A. Tissue distribution of perfluoroalkyl acids and health status in wild Mozambique tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) from Loskop Dam, Mpumalanga, South Africa. J. Environ. Sci. 2017, 61, 59–67. 10.1016/j.jes.2017.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J. W.; Whittle D. M.; Muir D. C. G.; Mabury S. A. Perfluoroalkyl Contaminants in a Food Web from Lake Ontario. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 5379–5385. 10.1021/es049331s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J. W.; Mabury S. A.; Solomon K. R.; Muir D. C. Bioconcentration and tissue distribution of perfluorinated acids in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2003, 22, 196–204. 10.1002/etc.5620220126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniyasu S.; Kannan K.; Horii Y.; Hanari N.; Yamashita N. A Survey of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate and Related Perfluorinated Organic Compounds in Water, Fish, Birds, and Humans from Japan. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 2634–2639. 10.1021/es0303440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conder J. M.; Hoke R. A.; Wolf W.; Russell M. H.; Buck R. C. Are PFCAs Bioaccumulative? A Critical Review and Comparison with Regulatory Criteria and Persistent Lipophilic Compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 995–1003. 10.1021/es070895g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda D. A.; Benskin J. P.; Awad R.; Lepoint G.; Leonel J.; Hatje V. Bioaccumulation of Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in a tropical estuarine food web. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 142146 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.