Abstract

Executive functioning (EF) skills contribute positively to mental and physical health across the lifespan. High-quality parenting is associated with better child EF. However, research has largely focused on the contributions of mothers’ parenting and failed to apply a family systems perspective to more comprehensively consider the consequences of parenting quality and coparenting relationship quality for the development of children’s EF. This study examined the independent and joint contributions of mothers’ observed parenting, fathers’ observed parenting, and supportive coparenting during infancy to children’s attention in toddlerhood (26 months) and aspects of EF (i.e., inhibitory control and impulsivity) at 7.5 years of age. Data came from a study of 166 families who participated in a larger longitudinal study. Assessments were conducted at 9-months postpartum (n = 158), 26-months postpartum (n = 114), and when children were 7.5 years of age (n = 100). Results indicated statistically significant associations between fathers’ parenting quality at 9-months postpartum and greater child inhibitory control at 7.5 years of age. Mothers’ parenting quality at 9-months postpartum was associated with better child attention in toddlerhood. Supportive coparenting was not directly associated with toddler or child EF. However, supportive coparenting moderated the association between fathers’ parenting quality and child impulsivity, such that the adjusted effect of fathers’ parenting on child impulsivity was negative when supportive coparenting was high. Findings highlight the importance of considering the development of child EF within a family systems framework.

Keywords: parenting, executive functioning, coparenting, inhibitory control, fathers

Executive functioning (EF) refers to higher-order cognitive processes necessary for goal-oriented actions, such as drawing a picture, building a structure with blocks, or completing a puzzle (Garon, Bryson & Smith, 2008). At the transition to formal schooling, advancements in children’s EF enable more complex way of thinking that facilitates academic performance (Hughes, Ensor, Wilson & Graham, 2009; Roebers et al., 2014). Both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies suggest that children’s performance on EF measures is one of the best predictors of success during the early years of formal schooling and beyond (Blair, 2002; Blair & Razza, 2007). However, children’s emerging EF skills vary. Environmental factors, like the quality of the early caregiving environment, may be particularly influential on young children’s emerging EF (Phillips & Shonkoff, 2000).

The present study considered the development of children’s EF within the context of the family system (Cox & Paley, 2003). The first goal of this study was to evaluate whether observations of fathers’ parenting quality during infancy supported greater EF during toddlerhood and when children were 7.5-years of age, while controlling for observations of mothers’ parenting quality. A second goal of this study was to examine the contributions of observed supportive coparenting, or the extent to which parents cooperate and validate each other’s parenting, during infancy to later EF. Finally, consistent with a family systems framework, a third goal was to examine whether mothers’ and fathers’ parenting quality during infancy jointly contributed to the development of EF. We also considered whether observed supportive coparenting moderated associations between fathers’ parenting quality and child EF.

The Development of Executive Functioning

Executive functioning (EF) includes higher-order cognitive abilities and self-regulation processes, such as attention, inhibitory control, and low impulsivity (Hughes et al., 2009). Successful goal achievement requires drawing upon multiple, sometimes conflicting, aspects of EF. The dual systems perspective highlights the roles of impulsive and reflective systems in driving a child’s behavior (Hoffman, Friese & Straw, 2009). The impulsive system includes automatic behaviors that occur relatively instinctively and require fewer cognitive resources, whereas the reflective system depends on relatively slow and controlled cognitive processes (Hofmann et al., 2009; Smith & DeCoster, 2000). Included in the reflective system is children’s inhibitory control, or their ability to suppress a dominant response to exhibit a sub-dominant response and thus respond correctly or more appropriately in a situation (Macdonald, Beauchamp, Crimean & Anderson, 2014). Children with greater levels of inhibitory control and low impulsivity are better able to maintain concentration and achieve a desired outcome (Diamond, Kirkham & Also, 2002; Macdonald et al., 2014).

In adulthood, EF can be described as a single component, which coordinates and activates multiple cognitive functions (Miyake & Friedman, 2012). However, the process whereby separate aspects of EF emerge and integrate into a single component is debated, with some suggesting that a single EF component is evident in the preschool years and others pointing to a multi-factor structure (Hughes et al., 2009; Mulder, Hoofs, Verhagen, van der Veen, & Leseman, 2014). Researchers agree that key aspects of EF emerge in the first year of life as the prefrontal cortex develops and children receive stimulation from their environment (Blankenship et al., 2019). For example, infants improve in their ability to disengage attention from a stimulus during the first 4 months (McConnell & Bryson, 2005), and inhibitory control is evident in infants as young as 8 months of age (Bell, 2001). As children transition to formal schooling, the changing environmental demands challenge children and require activating aspects of EF. Although the components of EF continue to develop beyond middle childhood (Best, Miller & Jones, 2009), children who can draw upon strong EF skills (i.e., selectively attending, inhibiting the dominant response) are most likely to adapt successfully to new challenges.

The Family System as an Important Developmental Context

Family systems theory views the family as an interdependent network of subsystems (i.e., parent-child relationship) that shape an individual’s development (Minuchin, 1974). Key to family systems theory is the notion that the family is a self-correcting system, whereupon patterns of behavior operate to keep the family at homeostasis. As such, the quality of interactions in a single subsystem (i.e., parent-child) can directly contribute to the development of child EF (Cox & Paley, 2003). Alternatively, two family subsystems may jointly contribute to child EF. For example, the quality of one family subsystem (i.e., coparenting) may strengthen or attenuate the effects of another family subsystem (i.e., parent-child) on child EF.

The Role of Parenting Quality

High-quality parenting provides opportunities for children to refine and strengthen synaptic connections in the prefrontal cortex, which support emerging EF skills (Rothbart, Sheese, Rueda & Posner, 2011). A majority of research examining associations between parenting and child EF has focused on mothers (Fay- Stammbach, Hawes & Meredith, 2014). In infancy, mothers’ mind-mindedness at 9-months predicted greater inhibitory control and better performance on delay of gratification EF tasks at 2 and 3 years (Cheng, Lu, Archer, & Wang, 2018). Additionally, Bernier, Carlson, Deschênes and Matte-Gagné (2012) reported that maternal autonomy support at 12–15 months predicted greater child EF at 18 months. In toddlerhood, mothers’ autonomy support (Hughes & Ensor, 2009; Matte-Gagné, Bernier & Lalonde, 2015) and sensitivity (Blair, Raver & Berry, 2014) are associated with better inhibitory control, attention, and cognitive flexibility in early childhood. In contrast, negative parenting in early childhood, such as hostility/rejection and control, have been associated with reduced inhibitory control later in development (Fay- Stammbach et al., 2014). Researchers have suggested that the presence of sensitive responding in the first year of life may be critical for the development of child EF (Cheng, Lu, Archer, & Wang, 2018). Later on, once children become verbal, behaviors like autonomy support (in combination with sensitivity) may be most salient for child EF (Bernier et al., 2012).

Fathers’ are increasingly involved in children’s lives (Schoppe- Sullivan & Fagan, 2020), and have the potential to make important contributions to children’s EF (Cabrera, Fitzgerald, Bradley & Roggman, 2014; Majdandžić, Möller, de Vente, Bögels & van den Boom, 2014). Emerging research suggests fathers engage in a more stimulating and challenging style of interaction than mothers, which can support emerging EF (Karberg, Cabrera, Malin & Kuhns, 2019). Although research examining associations between fathers’ parenting and child EF is sparse, emerging evidence indicates fathers make independent contributions to child EF. Lucassen et al. (2015) reported distinct associations of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting with child EF; lower mothers’ sensitivity and greater fathers’ harsh parenting predicted lower scores on child metacognition and inhibitory control at 3 years. Others have reported associations between fathers’ greater sensitivity during infancy (Towe-Goodman et al., 2014) and greater autonomy support in early childhood (Meuwissen & Carlson, 2018) and stronger child EF.

The Role of Supportive Coparenting

Although independently observing mother-child or father-child interactions provides insight into the quality of parenting behaviors within each respective dyad, isolated interactions do not capture the nature of the broader family system. Rather, family systems theorists emphasize the importance of including measures of the coparenting relationship, or the “executive subsystem” of the family (Minuchin, 1974). As the executive subsystem, the quality of coparenting-related interactions between caregivers may have an especially powerful impact on other family members and subsystems. When coparenting relationships are characterized by supportive and cooperative behaviors between parents, the overall emotional climate of the family is more positive and, in turn, children benefit (Teubert & Pinquart, 2010).

Multiple studies have reported direct associations between supportive coparenting and child social-emotional adjustment, including reduced externalizing, dysregulation, and internalizing problems (Altenburger, Lang, Schoppe-Sullivan, Kamp Dush & Johnson, 2017; Farr, Bruun & Patterson, 2019). However, to our knowledge, this is the first study to consider the direct contributions of supportive coparenting to children’s EF. It is common for children to have more than one caregiver who together teach, discipline, and develop close relationships with them (Volling, Kolak, & Blandon, 2009). Thus, by incorporating observations of supportive coparenting, this study aims to more comprehensively consider the development of child EF within the “whole family” dynamic.

Joint Contributions of Family Subsystems

A family systems framework also suggests that individual subsystems within the family may jointly contribute to the development of child EF. From this perspective, mothers’ and fathers’ parenting quality may interactively predict child EF. Perhaps if the quality of parenting within one parent-child subsystem is low, high-quality parenting in another parent-child subsystem may buffer the child from potential adverse consequences. To our knowledge, only one study has examined interactions between mothers’ and fathers’ parenting in toddlerhood as a predictor of reported EF (i.e., inhibition, flexibility, and metacognition) in kindergarten (Hertz, Bernier, Cimon-Paquet & Reguerio, 2019). These researchers did not find a statistically significant interaction. However, they suggested the null result could be due to their small sample size or the different contexts in which they measured parenting quality (i.e., snack time with mom and play time with dad).

Additionally, supportive coparenting may moderate associations between parenting quality and child EF. The coparenting relationship might be especially likely to moderate the association between fathers’ parenting quality and child EF, as prior research has indicated that the father-child subsystem is more vulnerable to coparenting relationship quality than the mother-child subsystem (Kopystynska, Barnett & Curran, 2020). Thus, in the presence of a highly supportive coparenting relationship, high quality parenting among fathers might be more strongly associated with child EF. Alternatively, in the context of low supportive coparenting and low fathers’ parenting quality, children might face the greatest risk for EF difficulties. This is the first study to examine whether coparenting relationship quality moderates the association between fathers’ parenting quality and child EF. However, prior research has indicated that supportive coparenting moderated associations between father involvement and child social-emotional adjustment, such that father involvement was associated with better child social-emotional adjustment only when supportive coparenting was high (Jia, Kotila & Schoppe-Sullivan, 2012).

The Present Study

The present study considered the development of child EF within a family systems framework via three primary aims: 1) Examine whether observations of fathers’ parenting quality during infancy supported greater EF during toddlerhood and when children were 7.5-years-old, while controlling for observations of mothers’ parenting quality. We expected that fathers’ parenting quality would positively contribute to children’s EF, above and beyond the contributions of mothers’ parenting quality. 2) Examine the contributions of supportive coparenting during infancy to EF during toddlerhood and when children were 7.5-years-old. We expected positive associations between supportive coparenting and children’s EF. 3) Evaluate whether family subsystems interacted to predict child EF. We tested whether mothers’ parenting quality interacted with fathers’ parenting quality to predict child EF. We hypothesized that high-quality parenting from one parent may buffer the adverse effects of low-quality parenting by the other to promote positive child outcomes. We also tested whether supportive coparenting moderated associations between fathers’ parenting quality and child EF. We expected that higher fathers’ parenting quality would be associated with stronger child EF in the presence of a supportive coparenting relationship.

Additional control variables that prior research has linked to children’s EF—including infant effortful control (Zhou, Chen & Main, 2012), infant negative affect (Bridgett, Oddi, Laake, Murdock & Bachmann, 2013), and family socioeconomic status (Sarsour et al., 2011)—were included in analyses, as was gender and child age, given that older children are likely to perform better on EF tasks.

Method

Participants

Data come from a sample of 166 dual-earner families residing in the U.S. who participated in a longitudinal study (n = 182) of the transition to parenthood beginning in 2008. Participant recruitment occurred from childbirth education classes, pregnancy health centers, and through advertisements posted online, at doctor’s offices, and in newspapers. Eligible participants were required to be married or cohabiting for at least 3 months, 18 years of age or older, expecting their first biological child, able to read and speak English, currently employed full-time and planning to return to work postpartum, and planning to stay in the area for at least one year. Informed consent was obtained from each parent at each phase of the study, and the university IRB approved all procedures.

Among participants included in this study (n = 166), the median level of education was a bachelor’s degree, as 77% of mothers and 66% of fathers reported having at least this education level. Median annual household income was $78,217. On average, mothers were 28.4 years old (SD = 4.0; Range = 18 – 42), and 86% percent White, 6% Black, 2% Asian, 2% other races, and 4% multi-racial. Fathers were 30.2 years old (SD = 4.58; Range = 18 – 48), and 86% White, 6% Black, 3% Asian, 4% other races, and 1% multi-racial. Note, parents who indicated more than one race were considered “multi-racial”. On a separate question, parents were asked, “Are you of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin?” Three percent of mothers and 2% of fathers identified as Hispanic. Eighty-nine percent of couples indicated they were married, while the remaining 11% were cohabiting and in a romantic relationship at the time of the initial wave of data collection. At Wave 3, six families reported separation or divorce since the focal child was born.

Procedure

This study focused on associations between observations of parenting and supportive coparenting when infants were approximately 9-months of age (Wave 1; n = 158) and aspects of EF when children were 26-months-old (Wave 2; n = 114; M = 26.42, SD = 13.13) and 7.5 years old (Wave 3; n = 100; M = 7.78; SD = .44). Of note, 8 families only had data at Wave 2 (n = 1) or Wave 3 (n = 7). When infants were 9-months-old, parents and their infants visited a large science center together for approximately 1.5 hours during which they were asked to play individually with their infant to assess parenting quality, as well as together with the child to elicit coparenting behaviors. At Wave 1, 158 families from the original sample participated and had data on at least one of the following variables: mothers’ parenting quality, fathers’ parenting quality, or supportive coparenting. One hundred and forty-eight families had data on all three of these variables, and the remaining 10 families had some combination of data present (i.e., mothers’ parenting and supportive coparenting).

Two additional follow-up data collection efforts took place. First, at Wave 2, mothers reported on aspects of their toddler’s development via a survey that was sent to them in the mail. Second, at Wave 3, families were invited to visit the laboratory for approximately 2.5 hours, wherein observational assessments were administered to the child and questionnaires to the parents. Of the original sample, 100 families reported data on child impulsivity and 88 children completed a measure of inhibitory control.

Missing Data and Attrition Analyses

Participants in the current sample were drawn from a larger study of 182 families. We removed one of the families because their child had a severe cognitive and physical delay and could not participate in tasks at the 7.5-year time point. Fifteen of the remaining 181 families had missing data on all variables of interest in this study and only had data on demographic characteristics from earlier waves of the study. Therefore, these 15 cases were removed from the analysis. The remaining 166 cases (91.7%) had data on at least one variable of interest in the current study and demographic characteristics and were, thus, included in all further analyses. Table 1 indicates the number of families that participated in each phase of the study, including attrition rates. Of families who had data on a variable of interest at Wave 1 (n = 158), 58.9% (n = 93) families also had data at Wave 3. Of families who participated Wave 2 (n = 114), 67.5% also had data at Wave 3.

Table 1.

Study participation and attrition rates

| Data Collection Time Point | Participating Families (out of 181) | Study Participation Rate (# of participating families / total families enrolled in study) | Study Attrition Rate (# of missing families / total families enrolled in study) | Wave 1 Attrition Rate (# of missing families / total families enrolled in Wave 1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Wave 1 (9 months) | 158 | 87.3% | 12.7% | 0% |

| Wave 2 (26 months) | 114 | 63.0% | 37% | 27.8% |

| Wave 3 (7.5 years) | 100 | 55.2% | 44.8% | 36.7% |

Note. The number of “participating families” represents the number of families who had data on at least one variable of interest at each wave of the study. However, there were various patterns of participation, with some families only participating in one wave and others only participating in two waves (i.e., Wave 1 and Wave 3).

Attrition analyses were conducted among families who participated at Wave 1 (n = 158) to evaluate whether there were statistically significant differences between families who participated at Wave 1 and Wave 2 (n = 113) and families who participated at Wave 1 but did not participate at Wave 2 (n = 45). To conduct the attrition analyses, we created a dummy variable in which families who participated at Wave 1 and Wave 2 were coded as 1 and families who participated at Wave 1 (but not Wave 2) were coded as 0. There were no differences between groups on supportive coparenting (t(150) = −1.94, p > .05), fathers’ parenting quality (t(150) = −1.72, p > .05), or mothers’ parenting quality (t(153) = −1.12, p > .05).

To compare whether families who participated at Wave 3 differed from families who did not on variables of interest, we created a dummy variable in which families who participated at Wave 1 and Wave 3 were coded as 1 and families who participated at Wave 1 (but not Wave 3) were coded as 0. There were not statistically significant differences between groups on supportive coparenting (t(150) = −0.65, p > .05), fathers’ parenting quality (t(150) = −1.61, p > .05), or mothers’ parenting quality(t(153) = −1.20, p > .05).

Measures

Parenting and Coparenting (Wave 1)

Observed Parenting Quality

Parenting quality was assessed separately for fathers and mothers in a 5-minute task using the Parent-Child Coding Manual, adapted from Cox and Crnic (2002). Each parent was asked to try to teach their child how to play with either a shape sorter or stacking rings toy. Which parent went first and which toy they used was determined randomly. Trained research assistants coded these dyadic interactions for behaviors indicative of parenting quality on a 5-point scale: sensitivity (1 = parent rarely responds appropriately to child’s cues; 5= parent responds quickly and appropriately to child’s distress), detachment (1 = no signs of detachment; 5 = parent is not emotionally involved with child and appears to be “just going through the motions”), and positive regard (1 = parent shows very little positive regard; 5 = parent is exceptionally positive in their facial and vocal expressiveness and behavior).

Coders overlapped on 100% of the episodes. Inter-rater reliability was acceptable for both mothers’ and fathers’ sensitivity (γmother = 0.72; γfather = 0.77), detachment (γmother = 0.71; γfather = 0.70), and positive regard (γmother = 0.80; γfather = 0.83). Strong intercorrelations between dimensions of fathers’ parenting quality (absolute value ranging from 0.63 to 0.73) and between dimensions of mothers’ parenting quality (absolute value ranging from 0.66 to 0.73) supported the construction of composite parenting quality variables. These variables were created separately for each parent by averaging sensitivity, detachment (reverse scored), and positive regard, with higher scores indicating higher-quality parenting behavior.

Supportive Coparenting Quality

Observations of supportive coparenting quality were obtained at 9-months postpartum from mother-father-infant interaction episodes, in which parents were given a novel toy (Jack-in-the-box) and asked to introduce the toy to their child for 5 minutes. The introduction of a toy that could startle the child was selected with the goal of placing the child in an uncertain situation that could provoke varying levels of supportive coparenting behavior. Informed by scales developed by Cowan and Cowan (1996), trained research assistants rated the quality of parents’ coparenting behavior on a scale of 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater levels of the particular behavior being evaluated. The scales included in this study focused on coparenting cooperation (i.e., extent to which parents emotionally and instrumentally support their partner’s parenting strategies) and competition (i.e., extent to which parents vie for the child’s attention), which were both coded at the couple level. Additionally, warmth (i.e., affection toward partner in relation to their child) and pleasure (i.e., degree to which parents take delight in how their partner interacts with their child), which were coded at the individual level, were included. A composite coparenting warmth variable was created by averaging mothers’ and fathers’ warmth (r = 0.76; p < .001). Second, a composite coparenting pleasure variable was created by averaging mothers’ and fathers’ pleasure (r = 0.77; p < .001). Statistically significant intercorrelations between coparenting cooperation, competition, average coparental warmth and average coparental pleasure ranged from an absolute value of .54 to .88, supporting the construction of a single latent supportive coparenting variable. Coders overlapped on 56.2% randomly selected episodes. Inter-rater reliability for supportive coparenting behavior was acceptable for cooperation (γ = 0.80), competition (γ = 0.64), mothers’ pleasure (γ = 0.84), fathers’ pleasure (γ = 0.86), mothers’ warmth (γ = 0.76), and fathers’ warmth (γ = 0.76).

Child EF (Wave 2)

Toddler Attention

Mothers reported on their toddler’s attention using the widely-used and validated Infant-Toddler Social-Emotional Assessment (ITSEA; Carter, Briggs-Gowan, Jones & Little, 2003), which is appropriate for children from 12 to 48 months old1 (Briggs-Gowan, Carter, Bosson-Heenan, Guyer & Horwitz, 2006). Although the ITSEA is largely designed to capture social-emotional development, it includes an attention subscale, which is an aspect of EF (Bridgett et al., 2013). This subscale required mothers to respond to 5 questions about their child’s attention (i.e., “can pay attention for a long time”) on a scale ranging from 0 (not true/rarely) to 2 (very true/often); α = 0.66.

Child EF (Wave 3)

Child Inhibitory Control

A computerized flanker task, from the NIH Toolbox Cognitive Function Battery (Zelazo et al., 2013), was administered on an iPad to measure inhibitory control. Participating children were presented with a row of stimuli (fish or arrows) and pressed one of two buttons indicating the direction of the middle stimulus. The task required participants to focus on the middle stimulus while inhibiting attention to additional stimuli flanking it. In “congruent” trials the middle stimulus is pointing in the same direction as the “flankers,” and in “incongruent” trials the middle stimulus is pointing in the opposite direction as the flankers. Scoring followed the recommendations outlined in the NIH Toolbox Scoring and Interpretation Guide and included accuracy and reaction time vectors. Consistent with these guidelines, the reaction time and accuracy scores were summed to indicate overall inhibitory control (theoretical range from 0 to 10). Higher values indicated greater child inhibitory control.

Impulsivity

The Impulsivity Scale for Children (Tsukayama, Duckworth & Kim, 2013) was used to assess parents’ perceptions of children’s impulsivity—or inability to regulate behavior, attention, and emotions. Four items asked parents to report how frequently (1 = almost never; 5 = at least once a day) children displayed impulsive behaviors in the context of social interactions (i.e., “interrupted other people while they were talking”). Four additional items asked parents to report children’s impulsivity in the domain of school (i.e., “my child left something he/she needed for school at home”). Items were averaged to create a global impulsivity score (α = .76 for mothers and α = .83 for fathers). Parents’ perceptions of child impulsivity were strongly correlated (r = .51, p < .001), and thus were averaged. In 16 cases (14 mothers and 2 fathers) only one parent reported on child impulsivity; data were included from whichever parent reported on child impulsivity.

Control Variables

Child gender (0 = male; 1 = female), child age, infant effortful control, and infant negative affect were included as control variables. At 9-months postpartum, infant effortful control was assessed via mothers’ reports on the 37-item Revised Infant Behavior Questionnaire—Very Short Form (Rothbart & Gartstein, 2000). On a subset of 12 items, mothers rated the extent to which their child exhibited effortful control during the past week on a scale of 0 to 7, where 0 indicated that the behavior did not apply, 1 indicated that the behavior had never been observed, and 7 indicated that the behavior had very frequently been observed. A single effortful control variable was created by averaging these 12 items (i.e., “How often during the last week did the baby play with one toy or object for 5–10 minutes?”); α = 0.76. Additionally, a single variable representing infant negative affect was created by averaging 12 negative affect items (i.e., “How often did the baby seem angry when you left her/him in the crib?”); α = 0.83.

Family socioeconomic (SES) was also included as a control variable. Parents rated their education levels from 1 (“Less than high school”) to 8 (“Doctorate degree”). Approximate household income was also reported. Patterns of Spearman rho correlations indicated moderately strong associations between mothers’ and fathers’ education (ρ = .55, p <.001). There were also moderately strong associations between income and mothers’ education (ρ = .46, p < .001), as well as between income and fathers’ education (ρ = .48, p < .001). To approximate family SES, we created a single SES variable by standardizing and averaging parents’ education and income.

Results

Analytic Plan

First, descriptive statistics and intercorrelations for variables of interest were computed. Next, structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted in Mplus version 8.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017) to evaluate research questions. Compared to regression analysis, SEM removes measurement error from constructs of interest, reduces the number of observed variables into a smaller number of latent variables, and provides techniques for handling missing data (Bowen & Guo, 2011). Full Information Maximum Likelihood Estimation (FIML) was used to model missing data, as this method is considered superior to other methods, such as listwise deletion, because it reduces bias and increases statistical power (Enders, 2013). Variances for predictors were included in the model to address missing data via FIML (Muthén & Muthén, 2017).

A measurement model was tested for supportive coparenting quality (i.e., cooperation, competition, pleasure, and warmth) at 9-months postpartum. Fit was evaluated using criteria outlined by Hu and Bentler (1999). Namely, the chi-square indicates that the model fit the data adequately when non-significant; the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) should be above 0.95; and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) should be below 0.06. After evaluating the fit of the measurement model, a structural model was computed to evaluate whether fathers’ parenting quality and supportive coparenting quality at Wave 1 were linked to children’s attention at Wave 2 or inhibitory control and impulsivity at Wave 3, while controlling for mothers’ parenting quality, infant effortful control and negative affect, family SES, child age, and child gender.

Next, to examine whether mothers’ parenting quality interacted with fathers’ parenting quality to predict child EF, parenting quality variables were centered and interaction terms were computed to include in the model as predictors of child attention, impulsivity, and inhibitory control. To test whether supportive coparenting moderated the association between fathers’ parenting quality and child EF, we followed steps outlined by Maslowsky et al. (2015). Of note, fit indices have not been developed for models that include a latent variable interaction. However, Maslowsky et al. (2015) recommended conducting a log-likelihood-ratio difference test to examine whether the model with the latent variable fits the data significantly better than the model without the latent variable interaction. Because the log-likelihood-ratio test statistic follows a chi-square distribution, a chi-square difference test can be used to identify the better fitting model. In the event of a statistically significant interaction we used the Johnson-Neyman technique to identify the region of significance +/− 1SD of the mean (Johnson & Fay, 1950).

Sample size requirements for SEM are influenced by several factors, including the type of model, the strength of the indicator loadings, and the strength of the regressive paths (Wolf, Harrington, Clark & Miller, 2013). In the current study, a power analysis was conducted using Monte Carlo simulation (Muthén & Muthén, 2002). This method generates estimates of power for individual associations of interest and allows the researcher to specify the desired effect size. Based on prior research examining associations between parenting and child EF, we expected the hypothesized effects to be small to moderate (.20). Ten thousand data sets were generated to estimate the power to detect the specified effect. With N = 166, power to detect main effects ranged from .72-.74.

Preliminary Results

Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations

Descriptive statistics for study variables of interest are presented in Table 2. On average, fathers (3.08 on a 5-point scale) and mothers (3.25 on a 5-point scale) showed moderate parenting quality. Observed supportive coparenting behavior was relatively high, as average coparenting cooperation was high (3.98 on a 5-point scale), average coparenting competition was low (1.61 on a 5-point scale), average coparenting pleasure was high (3.83 on a 5-point scale), and average coparenting warmth was high (3.70 on a 5-point scale). Children exhibited moderate levels of impulsivity (2.79 on a 5-point scale), moderate levels of attention (1.56 on a 3-point scale), and relatively high levels of inhibitory control (7.08 on a 10-point scale). Intercorrelations among fathers’ parenting quality, mothers’ parenting quality, coparenting relationship quality, and children’s attention, impulsivity, and inhibitory control are also included in Table 2.

Table 2.

Intercorrelations and descriptive statistics for variables of interest

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Wave 1 | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| 1. Parenting Quality_F | -- | |||||||||||

| 2. Parenting Quality_M | .21* | -- | ||||||||||

| 3. Cooperation | .26** | .26** | -- | |||||||||

| 4. Competition | −.17* | −.16+ | −.67** | -- | ||||||||

| 5. Coparenting Warmth | .37** | .22** | .80** | −.54** | -- | |||||||

| 6. Coparenting Pleasure | .36** | .24** | .80** | −.56** | .88** | -- | ||||||

| 7. Infant Effortful Control | −.05 | .13 | .08 | −.02 | .03 | .03 | -- | |||||

| 8. Infant Negative Affect | −.01 | −.02 | .02 | .02 | .03 | .01 | −.07 | -- | ||||

| 9. SES | .11 | .19* | .01 | −.03 | .02 | .01 | −.09 | −.20* | -- | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Wave 2 | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| 10. Attention | .03 | .30** | −.03 | .01 | .04 | .06 | .25** | −.19* | -- | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Wave 3 | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| 11. Inhibitory Control | .16 | −.11 | −.05 | .15 | −.04 | −.01 | −.11 | −23* | −.003 | .01 | -- | |

| 12. Impulsivity | −.19+ | −.16 | −.12 | .03 | −.11 | −.06 | −.06 | .10 | −.17 | −.21 | −.25* | -- |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Mean | 3.08 | 3.25 | 3.98 | 1.61 | 3.70 | 3.83 | 5.19 | 3.99 | .002 | 1.56 | 7.08 | 2.79 |

| SD | .58 | .54 | .95 | .81 | .90 | .95 | .69 | .99 | .83 | .35 | 1.21 | .76 |

| n | 152 | 155 | 152 | 152 | 152 | 152 | 153 | 153 | 165 | 114 | 88 | 100 |

p < .10;

p < .05;

p <.01;

Note: F = Father, M= Mother

Construction of Latent Variables

Patterns of intercorrelations (Table 2) supported the construction of a single latent variable representing parents’ supportive coparenting behavior, with coparenting cooperation, coparenting competition, coparenting pleasure, and coparenting warmth included as indicators. The errors of coparenting cooperation and competition were correlated. The measurement model fit the data well [χ2(1) = 0.56, p =.45; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = 0.000]. Furthermore, all factor loadings were statistically significant and the absolute value of the standardized loadings ranged from .59 to .94. Greater supportive coparenting was indicated by high cooperation, warmth, pleasure, and low competition (loaded negatively).

Structural Model Test

Next, a structural model testing supportive coparenting behavior and fathers’ parenting quality at 9-months postpartum as predictors of attention in toddlerhood and inhibitory control and impulsivity at 7.5-years of age was estimated (controlling for mothers’ parenting quality, child age, child gender, infant effortful control, infant negative affect, and family SES). The model fit the data well [χ2(45) = 51.90, p =.22; CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.03].

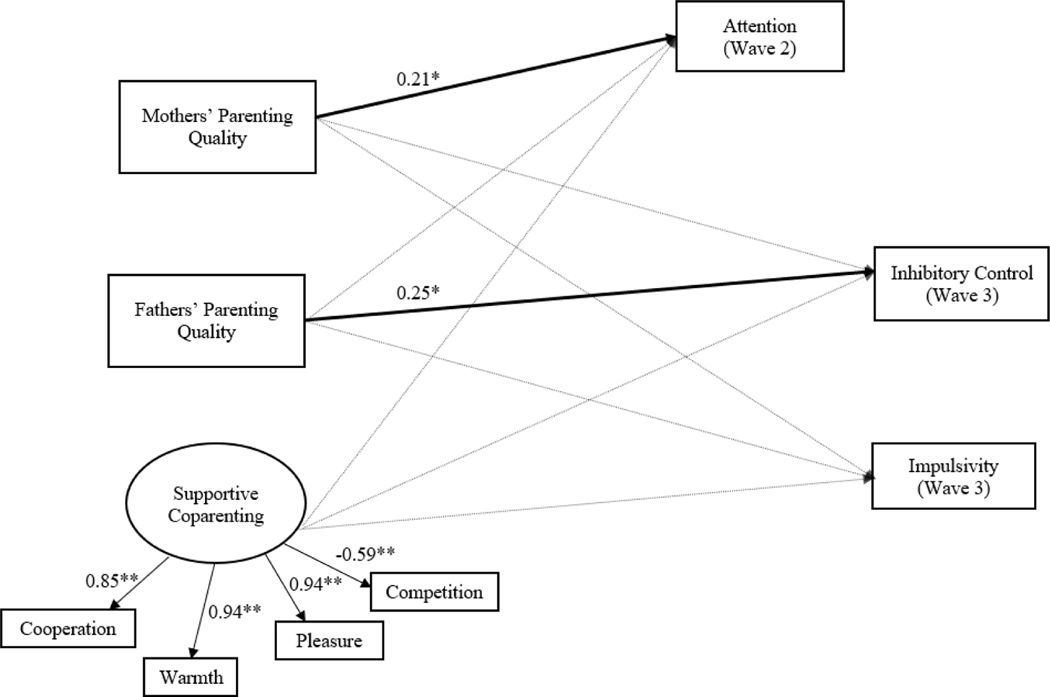

Notable statistically significant results are presented by domains of child EF. Elevated levels of toddler attention were predicted by mothers’ higher-quality parenting at Wave 1 (β = 0.21, p < 0.05). Other control variables—including infant negative affect (β = −0.19, p < .05), effortful control (β = 0.21, p < .05), and child age (β = 0.41, p < .001)—also emerged as statistically significant predictors of attention at Wave 2. Only child age statistically significantly predicted lower levels (β = −0.22, p < .05) of child impulsivity at 7.5 years. Greater child inhibitory control at Wave 3 was predicted by fathers’ higher-quality at Wave 1 (β = 0.25, p < 0.05). Infant negative affect also emerged as a statistically significant predictor (β = −0.24, p < 0.05) of children’s inhibitory control. Supportive coparenting was not associated with child EF. Standardized model results for statistically significant paths are reported in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Predictors of executive functioning in early childhood

Note. Control variables include infant negative affect, infant effortful control, child gender, child age, and family socioeconomic status. Only statistically significant paths are depicted in the model.

*p< .05; **p< .01

χ2(45) = 51.90, p = .22; CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.03

To test the joint contributions of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting quality to child EF an interaction term between mothers’ and fathers’ parenting quality was computed and included as a predictor of attention, impulsivity, and inhibitory control. The model fit the data well [χ2(49) = 55.35, p =.25; CFI = .99; RMSEA = 0.028]. The interaction term statistically significantly predicted impulsivity (β = −0.21, p < 0.05), but not attention (β = 0.11, p > 0.05) or inhibitory control (β = 0.07, p > 0.05). Thus, the paths predicting child attention and inhibitory control were removed. The model still fit the data well [χ2(51) = 57.47, p =.25; CFI = .99; RMSEA = 0.028; SRMR = 0.056]. However, the interaction term between mothers’ and fathers’ parenting quality as a predictor of child impulsivity was only approaching significance (β = −0.20, p = 0.06).

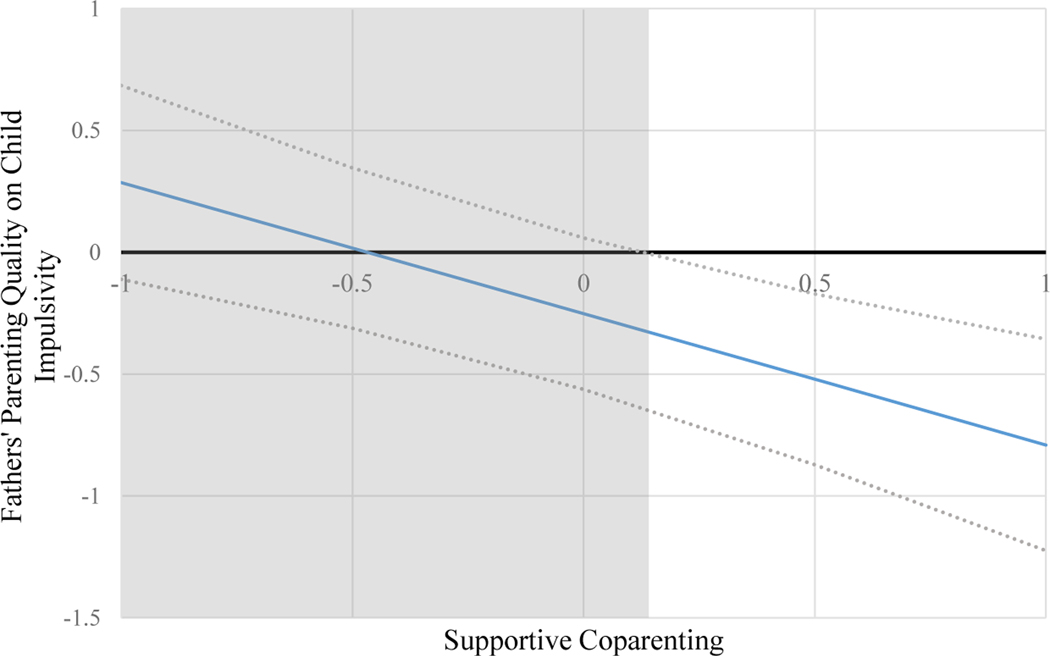

Next, we tested whether supportive coparenting moderated the association between fathers’ parenting quality and child EF. When supportive coparenting was added to the model the interaction between mothers’ parenting quality and fathers’ parenting quality remained a non-significant predictor of impulsivity (β = −0.06, p = 0.58). However, the interaction between supportive coparenting and fathers’ parenting quality statistically significantly predicted child impulsivity (β = −0.29, p < .001), but did not predict child attention (β = 0.15, p > .05) or inhibitory control (β = −0.09, p > .05). To interpret the most parsimonious model, we only included the interaction between supportive coparenting and fathers’ parenting quality as a predictor of child impulsivity in the final model. Standardized beta coefficients for the final model are presented in Table 3. Notably, the final model with the latent variable interaction had statistically better fit as indicated by a log-likelihood-ratio test (χ2(1) = 13.658, p < .001). Johnson-Neyman plots were used to identify regions of significance (Figure 2). When supportive coparenting was above average the adjusted effect of fathers’ parenting quality on child impulsivity was negative. Thus, greater fathers’ parenting quality predicted lower child impulsivity when supportive coparenting was high.

Table 3.

Path coefficients for structural equation model examining predictors of executive functioning at Wave 2 and Wave 3

| Path in SEM | β | Standard Error |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Wave 2 | ||

|

| ||

| Coparenting Support → Attention | −0.03 | 0.09 |

| SES → Attention | 0.02 | 0.09 |

| Gender → Attention | 0.03 | 0.08 |

| F_Parenting Quality → Attention | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| M_Parenting Quality → Attention | 0.21* | 0.08 |

| Effortful Control → Attention | 0.21* | 0.08 |

| Negative Affect → Attention | −0.18* | 0.08 |

| Child Age → Attention | 0.42*** | 0.08 |

|

| ||

| Wave 3 | ||

|

| ||

| Coparenting Support → Impulsivity | 1.58 | 0.40 |

| SES → Impulsivity | −0.09 | 0.09 |

| Gender → Impulsivity | −0.13 | 0.09 |

| F_Parenting Quality → Impulsivity | −0.18 | 0.11 |

| M_Parenting Quality → Impulsivity | −0.13 | 0.10 |

| Effortful Control → Impulsivity | −0.001 | 0.09 |

| Negative Affect → Impulsivity | 0.13 | 0.09 |

| Child Age → Impulsivity | −0.24** | 0.09 |

| F_Parenting Quality X Support → Impulsivity | −.31*** | 0.08 |

| Coparenting Support → IC | −0.02 | 0.11 |

| SES → IC | 0.07 | 0.10 |

| Gender → IC | 0.16 | 0.10 |

| F_Parenting Quality → IC | 0.25* | 0.11 |

| M_Parenting Quality → IC | −0.16 | 0.12 |

| Effortful Control → IC | −0.09 | 0.10 |

| Negative Affect → IC | −0.24* | 0.10 |

| Child Age → IC | 0.11 | 0.11 |

p < .05;

p <.01;

p < .001;

Note: F = Father, M= Mother, IC = Inhibitory Control

Figure 2.

Johnson-Neyman plots showing the adjusted effect of fathers’ parenting quality on child impulsivity. The shaded region indicates non-significance. The interaction was Examined +/− 1SD of the supportive coparenting mean.

Discussion

The present study applied family systems theory (Cox & Paley, 2003; Minuchin, 1974) to examine the contributions of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting quality and observed supportive coparenting during infancy to the development of children’s EF (i.e., attention, inhibitory control, impulsivity) from toddlerhood through the childhood years. As anticipated, findings indicated that greater fathers’ parenting quality, measured via direct observations, was associated with elevated levels of inhibitory control in children. More specifically, fathers’ sensitivity, positive affect, and engagement (i.e., reverse-scored detachment) measured in play interactions when children were 9-months-old predicted child inhibitory control, measured during a flanker task, when children were 7.5-years of age. Perhaps most notable, these findings emerged even after controlling for infant effortful control, negative affect, age, gender, SES, and mothers’ parenting quality. Observed mothers’ parenting quality when children were 9-months of age, in contrast, was not associated with children’s inhibitory control at 7.5-years. Thus, in addition to a body of research which has indicated that fathers’ high-quality parenting supports young children’s positive social and emotional adjustment (Schoppe- Sullivan & Fagan, 2020), findings revealed that fathers’ parenting quality during infancy sets the stage for inhibitory control when children are 7.5-years-old. Fathers’ parenting quality, however, was not directly associated with toddler attention or impulsivity when children were 7.5-years-old.

Findings also indicated that mothers’ parenting quality during infancy (i.e., 9-months) forecasted greater levels of child attention during toddlerhood. However, mothers’ parenting quality was not associated with any of the aspects of EF examined when children were 7.5-years-old (i.e., impulsivity and inhibitory control). Thus, the pattern of results suggests that the quality of mothers’—but not fathers’—parenting when children were 9-months of age was most consequential during toddlerhood. Although this pattern of results was not expected, findings highlight the independent contributions both parents make to the development of child EF across the early years of childhood.

Differences in the types of parenting behaviors mothers and fathers exhibit have been detected as early as infancy, with fathers typically engaging in interactions that are more stimulating, physical, and arousing than the interactions that take place between mother and child (Feldman, 2003). Prior research using time diaries has indicated that fathers spend more time with their children in play activities than they spend in caregiving (Kotila, Schoppe-Sullivan & Kamp Dush, 2013). Furthermore, theoretical perspectives on fathers’ parenting have suggested that during this time fathers provide high-intensity stimulation that challenges children to regulate their emotions and behaviors (Grossmann et al., 2002; Paquette, 2004). This type of play behavior during infancy provides the “building blocks” for children’s later EF. As such, this study provides support for the notion that fathers’ parenting during the infancy-toddler period has implications for the development of children’s inhibitory control later on in childhood. Further, our observations assessed positive parenting behaviors common to mothers and fathers to facilitate direct comparisons. However, future research should more carefully examine possible differences in the ways mothers and fathers interact with infants that could explain the different contributions of mothers and fathers to children’s EF. In addition, we focused on the general quality of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting behaviors in our analyses, but more fine-grained analyses of which specific aspects of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting are related to children’s EF would be a useful direction for future studies.

In our efforts to apply a family systems framework to better understand children’s EF, we also considered whether observed supportive coparenting quality at 9-months postpartum predicted elevated child EF during toddlerhood and childhood. Family systems theory suggests that “emergent systemic dynamics” occur when all family members are together (Volling, Kolak, & Blandon, 2009, p. 241). These dynamics cannot be understood by exclusively focusing on the quality of dyadic parent-child interactions. Results indicated that greater observed supportive coparenting behavior was not associated with higher levels of child EF in toddlerhood and childhood. This finding is somewhat surprising, as prior research has illustrated the importance of considering the coparenting relationship in the development of children’s social and emotional competence (Altenburger et al., 2017; McHale & Rasmussen, 1998; Teubert & Pinquart, 2010).

Although prior research has examined cross-sectional associations between supportive coparenting and children’s effortful control (see Karreman, Van Tuijl, Van Aken, & Deković, 2008), this was the first study (to our knowledge) to examine observed supportive coparenting behavior in infancy as a predictor of children’s EF in toddlerhood and childhood. In supportive coparenting interactions, parents effectively coordinate and reinforce each other’s messages, which should theoretically bolster children’s developing EF. It is possible, however, that parenting quality during infancy is a more proximal influence on the development of children’s EF. Perhaps children are more susceptible to low or high supportive coparenting environments as they get older. The structure of our data set did not allow us to test this possibility. However, future research should consider examining the consequences of coparenting relationship quality at various time points for children’s EF.

Consistent with a family systems perspective, which suggests that family subsystems may combine to influence child outcomes, we also considered whether mothers’ parenting and/or supportive coparenting moderated associations between fathers’ parenting quality and child EF. In the initial model, the interaction between mothers’ and fathers’ parenting quality statistically significantly predicted child impulsivity. However, when the interaction between fathers’ parenting quality and supportive coparenting was added to the model the interaction between mothers’ and fathers’ parenting quality was not statistically significant. Rather, greater father parenting quality was statistically significantly associated with reduced child impulsivity in the presence of high supportive coparenting.

This finding is particularly compelling, as it suggests that a supportive coparenting climate, in combination with fathers’ high-quality parenting, is especially beneficial for child EF. Additionally, this finding is consistent with the view that the coparenting relationship operates as the executive subsystem of the family. In other words, the quality of the coparenting relationship might be especially impactful on the quality of other relationships in the family system. Perhaps statistically significant interactions between dyadic parenting quality are more likely to be detected in samples of higher risk. In these types of environments, compensatory effects may emerge, wherein high-quality parenting on the part of either the mother or the father buffers the child from the potential adverse consequences of lower quality parenting from the other caregiver. Interactions between parenting quality should continue to be examined across diverse samples.

Limitations of the current study should be acknowledged A key study limitation is the lag between 26-months postpartum and 7.5 years of age. Additional points of data collection during this time period would have provided more insight into the precise nature of children’s EF development. Future research should consider more closely examining the role of fathers’ parenting quality and supportive coparenting behavior on child EF during this important developmental window. A second study limitation is the nature of the sample. In particular, the current sample is relatively low in risk and these children are less likely to have EF difficulties compared to children living in higher risk environments. It is possible that in lower SES environments, even stronger associations between parenting quality and EF may be detected. Additionally, six families separated or divorced during the course of this study. Although this number is too small to detect meaningful differences, future research should consider examining how separation or divorce impacts fathers’ parenting and children’s executive functioning.

Our observations of parenting and supportive coparenting quality were also relatively brief and assessed in separate dyadic and triadic contexts, respectively. However, parenting also takes place in triadic contexts in the presence of other parents, just as coparenting behavior can take place without both coparents present (i.e., covert coparenting processes; McHale, 1997). Thus, future research should work to conduct richer and more comprehensive observations of parenting and coparenting across different contexts and include more diverse families, including families of lower SES and families with non-resident fathers. Finally, an additional study limitation is the use of only mothers’ reports of toddler attention. Incorporating reports from multiple respondents may yield a more complete picture of toddler EF.

Conclusions and Implications

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study is unique in employing a family systems framework to examine the development of children’s EF from toddlerhood through the childhood years. By including and assessing both parents’ parenting quality and supportive coparenting relationship quality for their unique and joint contributions to child EF, multiple, interdependent aspects of the family system were considered simultaneously. Associations were uncovered between variables assessed in different contexts at different times—and across nearly 6 years. It is especially notable that the quality of fathers’ parenting in infancy had longstanding implications for children’s EF, even when controlling for a variety of other factors, including mothers’ parenting. Moreover, high levels of supportive coparenting appeared to enhance the benefits of fathers’ high-quality parenting for children’s EF. These findings support the emphasis of intervention programs for expectant and new parents on developing strong coparenting relationships (i.e., Feinberg & Kan, 2008), and policy efforts directed at increasing access to paternity leave for new fathers, as paternity leave supports engaged fathering and supportive coparenting (Petts & Knoester, 2020). As researchers continue to explore the underpinnings of children’s EF, they should apply a family systems perspective to better understand factors that support the development of EF. Strong EF skills, in turn, facilitate positive adjustment across the childhood years and beyond (Hughes et al., 2009).

Highlights.

Fathers’ parenting quality during infancy linked to child inhibitory control

Toddler attention supported by mothers’ parenting quality during infancy

Greater fathers’ parenting quality was associated with reduced child impulsivity in the presence of supportive coparenting

Family systems framework offers comprehensive view of child executive functioning

Acknowledgments

This paper and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NSF, NICHD, Pennsylvania State University, or The Ohio State University. The New Parents Project was funded by the National Science Foundation (CAREER 0746548, Schoppe-Sullivan), with additional support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD; 1K01HD056238, Kamp Dush), and The Ohio State University’s Institute for Population Research (NICHD R24HD058484) and program in Human Development and Family Science. We also acknowledge Claire M. Kamp Dush’s invaluable contributions to the design and execution of the New Parents Project. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

One child in our sample was 51 months old at Wave 2. We ran the final model with and without this case and the pattern of results did not change. Given that we also controlled for child age, we retained this case.

CRediT author statement

Lauren E. Altenburger: Conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, writing-original draft preparation

Sarah J. Schoppe-Sullivan: Writing-Review & Editing, funding acquisition, resources

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Altenburger LE, Lang SN, Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Kamp Dush CM, & Johnson S (2017). Toddlers’ differential susceptibility to the effects of coparenting on social–emotional adjustment. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 41(2), 228–237. 10.1177/0165025415620058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MA (2001). Brain electrical activity associated with cognitive processing during a looking version of the A-not-B task. Infancy, 2(3), 311–330. 10.1207/S15327078IN0203_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier A, Carlson SM, Deschênes M, & Matte-Gagné C (2012). Social factors in the development of early executive functioning: A closer look at the caregiving environment. Developmental Science, 15(1), 12–24. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2011.01093.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best JR, Miller PH, & Jones LL (2009). Executive functions after age 5: Changes and correlates. Developmental Review, 29(3), 180–200. 10.1016/j.dr.2009.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C (2002). Early intervention for low birth weight, preterm infants: The role of negative emotionality in the specification of effects. Development and Psychopathology, 14(2), 311–332. 10.1017/S0954579402002079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, Raver CC, & Berry DJ (2014). Two approaches to estimating the effect of parenting on the development of executive function in early childhood. Developmental Psychology, 50(2), 554–565. 10.1037/a0033647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, & Razza RP (2007). Relating effortful control, executive function, and false belief understanding to emerging math and literacy ability in kindergarten. Child Development, 78(2), 647–663. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01019.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenship TL, Slough MA, Calkins SD, Deater-Deckard K, Kim-Spoon J, & Bell MA (2019). Attention and executive functioning in infancy: Links to childhood executive function and reading achievement. Developmental Science, 22(6), e12824. 10.1111/desc.12824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen NK, & Guo S (2011). Structural equation modeling. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bridgett DJ, Oddi KB, Laake LM, Murdock KW, & Bachmann MN (2013). Integrating and differentiating aspects of self-regulation: Effortful control, executive functioning, and links to negative affectivity. Emotion, 13(1), 47–63. 10.1037/a0029536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs-Gowan MJ, Carter AS, Bosson-Heenan J, Guyer AE, & Horwitz SM (2006). Are infant-toddler social-emotional and behavioral problems transient? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(7), 849–858. 10.1097/01.chi.0000220849.48650.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera NJ, Fitzgerald HE, Bradley RH, & Roggman L (2014). The ecology of father-child relationships: An expanded model. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 6(4), 336–354. 10.1111/jftr.12054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Jones SM, & Little TD (2003). The infant–toddler social and emotional assessment (ITSEA): Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31(5), 495–514. 10.1023/A:1025449031360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng N, Lu S, Archer M, & Wang Z (2018). Quality of Maternal Parenting of 9-Month-Old Infants Predicts Executive Function Performance at 2 and 3 Years of Age [Original Research]. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(2293). 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CP, & Cowan PA (1996). Schoolchildren and their familes project: Description of co-parenting style ratings [Unpublished coding scales]. University of California [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, & Crnic K (2002). Qualitative ratings for parent-child interactions at 3–12 months of age [Unpublished manuscript ]. [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, & Paley B (2003). Understanding families as systems. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(5), 193–196. 10.1111/1467-8721.01259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A, Kirkham N, & Amso D (2002). Conditions under which young children can hold two rules in mind and inhibit a prepotent response. Developmental Psychology, 38(3), 352–362. 10.1037/0012-1649.38.3.352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK (2013). Dealing with missing data in developmental research. Child Development Perspectives, 7(1), 27–31. 10.1111/cdep.12008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farr RH, Bruun ST, & Patterson CJ (2019). Longitudinal associations between coparenting and child adjustment among lesbian, gay, and heterosexual adoptive parent families. Developmental Psychology, 55(12), 2547–2560. 10.1037/dev0000828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay- Stammbach T, Hawes DJ, & Meredith P (2014). Parenting influences on executive function in early childhood: A review. Child Development Perspectives, 8(4), 258–264. 10.1111/cdep.12095 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME, & Kan ML (2008). Establishing family foundations: intervention effects on coparenting, parent/infant well-being, and parent-child relations. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(2), 253–263. 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R (2003). Infant–mother and infant–father synchrony: The coregulation of positive arousal. Infant Mental Health Journal, 24(1), 1–23. 10.1002/imhj.10041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garon N, Bryson SE, & Smith IM (2008). Executive function in preschoolers: a review using an integrative framework. Psychological Bulletin, 134(1), 31–60. 10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann K, Grossmann KE, Fremmer- Bombik E, Kindler H, Scheuerer-Englisch H, Zimmermann, & Peter. (2002). The uniqueness of the child–father attachment relationship: Fathers’ sensitive and challenging play as a pivotal variable in a 16- year longitudinal study. Social Development, 11(3), 301–337. 10.1111/1467-9507.00202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz S, Bernier A, Cimon-Paquet C, & Regueiro S (2019). Parent–child relationships and child executive functioning at school entry: The importance of fathers. Early Child Development and Care, 189(5), 718–732. 10.1080/03004430.2017.1342078 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W, Friese M, & Strack F (2009). Impulse and self-control from a dual-systems perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(2), 162–176. 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01116.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CH, & Ensor RA (2009). How do families help or hinder the emergence of early executive function? New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2009(123), 35–50. 10.1002/cd.234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes C, Ensor R, Wilson A, & Graham A (2009). Tracking executive function across the transition to school: A latent variable approach. Developmental Neuropsychology, 35(1), 20–36. 10.1080/87565640903325691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia R, Kotila LE, & Schoppe-Sullivan SJ (2012). Transactional relations between father involvement and preschoolers’ socioemotional adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(6), 848–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PO, & Fay LC (1950). The Johnson-Neyman technique, its theory and application. Psychometrika, 15(4), 349–367. 10.1007/BF02288864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karberg E, Cabrera NJ, Malin J, & Kuhns C (2019). Longitudinal contributions of maternal and paternal intrusive behaviors to children’s sociability and sustained attention at prekindergarten. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 84(1), 79–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karreman A, Van Tuijl C, Van Aken MA, & Deković M (2008). Parenting, coparenting, and effortful control in preschoolers. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(1), 30. 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopystynska O, Barnett MA, & Curran MA (2020). Constructive and destructive interparental conflict, parenting, and coparenting alliance. Journal of Family Psychology, 34(4), 414–424. 10.1037/fam0000606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotila LE, Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, & Kamp Dush CM (2013). Time in parenting activities in dual-earner families at the transition to parenthood. Family Relations, 62(5), 795–807. 10.1111/fare.12037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucassen N, Kok R, Bakermans- Kranenburg MJ, Van Ijzendoorn MH, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Verhulst FC, Lambregtse- Van den Berg MP, & Tiemeier H (2015). Executive functions in early childhood: The role of maternal and paternal parenting practices. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 33(4), 489–505. 10.1111/bjdp.12112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald JA, Beauchamp MH, Crigan JA, & Anderson PJ (2014). Age-related differences in inhibitory control in the early school years. Child Neuropsychology, 20(5), 509–526. 10.1080/09297049.2013.822060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majdandžić M, Möller EL, de Vente W, Bögels SM, & van den Boom DC (2014). Fathers’ challenging parenting behavior prevents social anxiety development in their 4-year-old children: A longitudinal observational study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(2), 301–310. 10.1007/s10802-013-9774-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslowsky J, Jager J, & Hemken D (2015). Estimating and interpreting latent variable interactions: A tutorial for applying the latent moderated structural equations method. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 39(1), 87–96. 10.1177/0165025414552301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matte-Gagné C, Bernier A, & Lalonde G (2015). Stability in maternal autonomy support and child executive functioning. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(9), 2610–2619. 10.1007/s10826-014-0063-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell BA, & Bryson SE (2005). Visual attention and temperament: Developmental data from the first 6 months of life. Infant Behavior and Development, 28(4), 537–544. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2005.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McHale JP (1997). Overt and covert coparenting processes in the family. Family Process, 36(2), 183–201. 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1997.00183.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale JP, & Rasmussen JL (1998). Coparental and family group-level dynamics during infancy: Early family precursors of child and family functioning during preschool. Development and Psychopathology, 10(1), 39–59. 10.1017/S0954579498001527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuwissen AS, & Carlson SM (2018). The role of father parenting in children’s school readiness: A longitudinal follow-up. Journal of Family Psychology, 32(5), 588–598. 10.1037/fam0000418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin S (1974). Families and family therapy. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, & Friedman NP (2012). The nature and organization of individual differences in executive functions: Four general conclusions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(1), 8–14. 10.1177/0963721411429458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder H, Hoofs H, Verhagen J, van der Veen I, & Leseman PP (2014). Psychometric properties and convergent and predictive validity of an executive function test battery for two-year-olds. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 733. 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2002). How to use a Monte Carlo study to decide on sample size and determine power. Structural equation modeling, 9(4), 599–620. 10.1207/S15328007SEM0904_8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Paquette D (2004). Theorizing the father-child relationship: Mechanisms and developmental outcomes. Human Development, 47(4), 193–219. 10.1159/000078723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petts RJ, & Knoester C (2020). Are parental relationships improved if fathers take time off of work after the birth of a child? Social Forces, 98(3), 1223–1256. 10.1093/sf/soz014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DA, & Shonkoff JP (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roebers C, Röthlisberger M, Neuenschwander R, Cimeli P, Michel E, & Jäger K. (2014). The relation between cognitive and motor performance and their relevance for children’s transition to school: A latent variable approach. Human Movement Science, 33, 284–297. 10.1016/j.humov.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, & Gartstein MA (2000). The Revised Infant Behavior Questionnaire -- Very Short Form [Unpublished questionnaire]. University of Oregon. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Sheese BE, Rueda MR, & Posner MI (2011). Developing mechanisms of self-regulation in early life. Emotion Review, 3(2), 207–213. 10.1177/1754073910387943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarsour K, Sheridan M, Jutte D, Nuru-Jeter A, Hinshaw S, & Boyce WT (2011). Family socioeconomic status and child executive functions: The roles of language, home environment, and single parenthood. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society: JINS, 17(1), 120. 10.1017/S1355617710001335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoppe- Sullivan SJ, & Fagan J (2020). The evolution of fathering research in the 21st century: Persistent challenges, new directions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 175–197. 10.1111/jomf.12645 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ER, & DeCoster J (2000). Dual-process models in social and cognitive psychology: Conceptual integration and links to underlying memory systems. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(2), 108–131. 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0402_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teubert D, & Pinquart M (2010). The association between coparenting and child adjustment: A meta-analysis. Parenting: Science and Practice, 10(4), 286–307. 10.1080/15295192.2010.492040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Towe-Goodman NR, Willoughby M, Blair C, Gustafsson HC, Mills-Koonce WR, & Cox MJ (2014). Fathers’ sensitive parenting and the development of early executive functioning. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(6), 867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukayama E, Duckworth AL, & Kim B (2013). Domain- specific impulsivity in school-age children. Developmental Science, 16(6), 879–893. 10.1111/desc.12067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volling BL, Kolak AM, & Blandon AY (2009). Family subsystems and children’s self-regulation. In Olson SL & Sameroff AJ (Eds.), Biopsychosocial regulatory processes in the development of childhood behavioral problems (pp. 238–257). Cambridge [Google Scholar]

- Wolf EJ, Harrington KM, Clark SL, & Miller MW (2013). Sample size requirements for structural equation models: An evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 73(6), 913–934. 10.1177/0013164413495237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelazo PD, Anderson JE, Richler J, Wallner- Allen K, Beaumont JL, & Weintraub S II (2013). . NIH Toolbox Cognition Battery (CB): Measuring executive function and attention. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 78(4), 16–33. 10.1111/mono.12032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Chen SH, & Main A (2012). Commonalities and differences in the research on children’s effortful control and executive function: A call for an integrated model of self-regulation. Child Development Perspectives, 6(2), 112–121. 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00176.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]