Abstract

In the current study, bi‐metal oxide hybrid nanocomposites prepared by cerium oxide (CeO2) nanoparticles are included into chitosan‐ZnO composites for developing the potential materials of dressing the wound. The wound healing effect of prepared hybrid nanocomposites was evaluated regarding the surface morphology, functional groups, thermal degradation and composite size. The antimicrobial activity of chitosan‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nano composites was tested against the pathogens of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. The hybrid nanocomposites containing CeO2‐based chitosan and ZnO nanoparticles were taken for optimum dressing included in the vivo studies on the excisional wounds in wistar rats. After 2 weeks, it is seen that the wound treated with CS‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nano composites consists of the significant dressing of nearly 100% compared with control which showed nearly 65% of wound closure. Finally, our reported results gave the proof in supporting the availability of CS‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nanocomposites contains the dressing of the wounds for the treatment.

Keywords: bi‐metal oxide, caesarean section surgery, hybrid nanocomposites, wound healing

Schematic diagram wound healing by bi‐metal oxide hybrid nanocomposite

1. INTRODUCTION

The treatment of healing a wound is the complex method that is influencing within the recovery of the functioning and simple anatomy of the tissues that is wounded. Simply, the wound healing method that consists of the phases of temporary overlapping: infection, remodelling and proliferation. 1 The segment of inflammatory dispels the cells that are damaged, pathogens and special debris through phagocytosis by making the way for the phases of proliferation. Therefore, the prolonged contamination abnormally motives the release of maximum inflammatory mediators, cytokinesis, cytotoxic enzymes and free radicals that purpose giant that damages the surrounding tissues. The excessive production of the free radicals moreover convinces the oxidative stress that is resulting in the negative effects of cytotoxic and put off in the recovery of the wound. 2 Therefore, creation of the agents of anti‐oxidation and anti‐inflammatory to curtail continual contamination and reduce more free radicals could be a vital method to enhance the recovery of the wounds. Due to the vacancies of sufficient oxygen and the reversible trans‐formation amongst Ce (IV) and Ce (III), CeO2 is studied extensively for the catalytic applications and controlled synthesis. 3 , 4 , 5 In the recent modern years, the nano particles of CeO2 could act as the scavengers of free radical with the excessive nitrogen spices and reactive oxygen that consists the radicals of hydrogen peroxide, nitric oxides, hydroxyl radicals and superoxide radicals, 6 horrifying developing interest in their capacity of biomedical application. Initially, natural studies have tested that the nanoparticles of CeO2 could prevent the disease related to stress, along with persistent ischemic stroke, 7 inflammation 8 and the disease related with neurological problems. 9 , 10 Similarly, the nanoparticle of CeO2 has been additionally stated to enhance up the process restoration of cutaneous wounds through enhancing the proliferation and migration of maximum vital pores and pores and skin forming cells. 11

Chitosan is the linear derivative of polysaccharide of chitin, and it is the biodegradable material with the best biocompatibility. This verifies the recovery of the wounds through the technique of granulation and re‐epithelialisation of the company in the tissues that are wounded, 12 , 13 that is similar to the activities of antimicrobial that are ought to be improved with the ions of antimicrobial metals like Ag+ and Cu2+ for yielding the top‐notch dressing of the wounds. 14 The chitosan comprises specific nanoparticles that are most drastically with the nanoparticles with antimicrobial silver that is a well‐known technique of inventing the dressings of the wound with more potent ability of recuperation. 15 , 16 , 17 Hence, the chitosan is composed of nanoparticles of CeO2 might also additionally need to likely combine their top‐notch anti‐oxidation and wound recuperation talents and moreover decorate the compatibility of the nanoparticles of CeO2 and then it obtains the powerful recuperation agent of recovering the wound. Recently, the advanced techniques based on nanotechnology are tremendously promising for achieving the troubles that are linked with the medical interventions that are conventional in nature. Moreover, the catalytic homes of the numerous nanoparticles of metal oxides are hospital for the growth of the modalities of oxidative strains that cause the issues in health. 18 Therefore, the functions of the software program of these nanoparticles of the metal oxides in the recovery of diabetic wound are to be explored thoroughly.

The nanoparticles of cerium oxides are confirmed for the showcase in the interest of enzyme‐mimetic and antioxidants in the natural systems. 19 Engineering of latest materials having healing applications is the main problem in the sector of biomedicine engineering. Therefore, this way, nanotechnology adds the nanomaterial with the exceptional physicochemical properties consisting of higher aspect ratio and massive ground location to amount in evaluation to one of the large dimensions. This nanomaterial can moreover divide the groups into the types of inorganic sources, herbal, and these are consistent with their own derived sources. The nanoparticles of metal oxides and metal (MONPs/MNPs) that encompass ZnO, CuO, Ag, Fe3O4, MgO NPs and Cu, and these are placed in the sector of inorganic particles. 20 Recently, the industrial and medical importance of the NPs has mostly acquired consideration. Therefore, the anti‐cancer, antimicrobial, anti‐diabetic and sports of wound recovery of the ZnO NPs were indicated in the abundant studies. Therefore, this way, the antibacterial properties and the properties of wound healing of ZnO NPs are having the intention in this review. 21

In recent years, the caesarean is a surgical intervention, and its generality has increased in several countries. 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 The complications of wound are the common morbidities in the following section of caesarean. 28 The generality of the disruption and infection in the wound after caesarean are reported as 3%‐15% and 2%‐42% in several studies and 6% in average speaking. 28 , 29 These affect the complication in the quality of the life of mother to anxiety, stress, health recovery and delay in the ability of mother, 30 and also these are related with the additional cost, and as a result, there should be an increase of the antibiotics in wide spectrum and hospitalisation and repairing the wound repeatedly. The treatments in the local are not used for the recovery of the wound in caesarean, and the oral antibiotics are mostly prescribed for the prevention of the infection. 31

Based upon the discussion in the above part, the goal of this work is to investigate the wound therapy in care and enhanced in vivo healing properties of chitosan‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nanocomposites after caesarean section surgery. The prepared hybrid nanocomposites were tested with the antibacterial activity against the pathogens like Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. After that, the main properties of the chitosan‐ZnO composites containing CeO2 nano composites are investigated, and the efficacy of wound healing of the nano composites of CeO2‐containing chitosan‐ZnO nano composites was compared with the sterile gauze that is convectional, and it was calculated on the excisional wound of the rats.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Chemicals

The solvents and the materials are purchased from the Merck (Germany) and Sigma‐Aldrich (USA), respectively, used without further purification.

2.2. Preparation of chitosan‐ZnO nanocomposites

At first, chitin (0.25 g) and ZnCl2 (15%) were dissolved in dilute acetic acid solution, and these are subjected to repeatedly stirring for more than 2 hours at 90°C bath temperature for obtaining the pale‐yellow coloured solution of chitin. Therefore, after that, the freshly prepared sodium hydroxide (45%) solution was micro added until the white colour formation of the chitosan‐ZnO hybrid composite.

2.3. Synthesis of chitosan‐ZnO/cerium oxide (CS‐ZnO/CeO2 ) hybrid nanocomposites

Prepared chitosan‐ZnO hybrid composite and Ce (NO3)3∙6H2O (cerium nitrate) with equal wt/vol (1:1) and then the liquefied solution of acetic acid are mixed in the beaker with a magnetic stirrer that is constant, and then the beaker solution was shifted to hot plate at 80°C for 2 hours. After, a newly prepared solution of NaOH (45% wt/vol) was drop wisely mixed until it turns to pale yellow colour precipitate, and it was endorsing to deposit in the room temperature for almost 24 hours. The excessive fluid was pulled out, and it was cleansed for several times and endorsed to settling for 30 minutes. The remaining portion was drained by a suction pump, and it is dehydrated for almost 2 hours at 110°C. The final product of CS‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nanocomposites was stored further characterisations.

2.4. Characterisation studies

The cooperation between the functional group of CS with the ZnO and CeO2 was investigated by Fourier‐transform infrared spectroscopy (FT‐IR) measurement “Perkin Elmer Spectrum GX spectrophotometer” using the sampling technique of ATR in the range of 4000‐400 cm−1. The surface morphology of the hybrid nano composites was analysed by using “FE‐SEM (Carl Zeiss AG, Jena, Germany)” that is operating at the accelerating voltage of 5‐20 kV after it is being laminated with gold. The crystallinity of hybrid nano composites was validated through X‐ray diffract meter (X'Pert PROPANalytical). The XRD was executed over the range of 10°‐90° with scan peed of 5°/min at step size of 0.02°.

2.5. In vitro cell viability study

The in vitro cytotoxicity study of prepared scaffold was determined in accordance with a previous report. 32 The NIH 3T3 fibroblast cells were cultured in a 96‐well plate on control, CS‐ZnO and CS‐ZnO‐CeO2 nanocomposites in DMEM media supplemented with 10% foetal serum and 1% antibiotics in 5% CO2 at 37°C. Then, the medium was replaced with various concentrations of the scaffold solutions and included in PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.4). Later, the incubated cell cultures were mixed with MTT assay reagent and blended the DMSO for liquidification of the Formosan crystals. Hence, the cell viability was observed by using a “multimode plate reader (Enspire, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, Massachusetts) at 570 nm, respectively.” 32 Therefore, the percentage of the cell viability of each and every hybrid nano composites was evaluated by using Formula (1):

| (1) |

2.6. In vivo animal study

To evaluate the study of recovery of wound, the healthier male “Wister albino rats” with weight of 150 g was adopted. As per ethical guidelines, all procedures and protocols were constituted (IAEC No). In this study, the animals were splitted into three groups that contain only 3 animals in each of the group. Group no. 1 as control (CS); group no. 2 as CS‐ZnO hybrid composite and group 3 as CS‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nanocomposite.

2.7. Wound closure study

The animals were anaesthetised to create the excision wounds. The hair was shaved on the region of dorsal thoracic about 1.5 cm away from the vertebral column using electric clipper. Once the excisional wound was created, it was left open and observed for infections. Then, the prepared CS‐ZnO and CS‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nanocomposite dressings were placed over the wound and monitored from day 0 to complete wound closure. 33 The wound site was measured planimetrically on day 0, 3, 6 and 12 and calculated the complete wound closure using Equation 2:

| (2) |

where A 0 is the initial wounded area on day zero and A i is the specific area of the wound on that specified day.

2.8. Histopathology study

The skin dermis and hypodermis were isolated, and the tissues were joined in the solution of 10% formalin. Later, in a microtome, the section of 4 to 5 μm was stained with the solution of haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for studying the structure of excision tissue. Hence, almost all the slides of stained‐glass were studied under the light microscope. 34

2.9. Antimicrobial activity

Antibacterial activity of control, CS‐ZnO/CeO2, CS‐ZnO and CS hybrid nano composites was tested against the pathogens like S. aureus and E. coli for using the method of agar diffusion. 35 Herein, the prepared agar media cultured with above said pathogens. Then, prepared hybrid nanocomposites were poured into the agar well and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. Hence, the zone of the inhibition was marked in mm and calculated as mean ± SD.

2.10. Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis standardised from the triplicated independent experimental results and presented with mean ± SD. Statistical one‐way analysis of variance was standardised using Student's t‐test with P ≤ 0.05 as significance value. All the statistical values were estimated using the Graph Pad prism (version 6.01) statistical software.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. FT‐IR spectral studies

Figure 1 shows the spectra of FT‐IR of neat CS polymer, CS‐ZnO and CS‐ZnO/CeO2 wound healing materials. In case of the chitosan, wider peak of characteristics was appeared at 3252 cm−1 that is corresponding for overlapping in the stretching vibration of N—H and —OH group shift in the nanocomposites of CS‐ZnO to the lower wavenumber to 3426 cm−1. Moreover, the absorption peak at 1636 cm−1 (amide group I), 1542 cm−1 (bending vibration of NH3) and 1065 cm−1 (stretching vibration of C—O—C of the glyosidic linkage) in the nano composites of CS‐ZnO shift to the lower wavenumber (Figure 1B) for the cooperation of all these group with ZnO and the formation of the hydrogen bond between chitosan polymer and ZnO. Hence, the agreement with previous reports is good. 36 The intense peak of FT‐IR was shown at 484 cm‐1 that is corresponding to the stretching vibration of Ce—O—Ce that is antisymmetric in nature. 37 All the bands of spectra are shown around the 400‐680 cm−1. Therefore, these peaks are assigned in the vibration mode of CeO2. The peaks of weak absorption are at the results of 2354 cm−1 in the bending vibration of the band of C‐H. Therefore, the larger band at 3435 cm−1 is present that is in the relation with the vibration of the OH group that is corresponding to the groups of residual water and hydroxyl group. 37 In addition, the functional spectra of ZnO and CeO2 nanoparticles were included in Table 1.

FIGURE 1.

Fourier‐transform infrared spectroscopy spectra of A as chitosan (CS), B as chitosan‐ZnO (CS) and C as chitosan‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nanocomposites as wound dressing materials

TABLE 1.

Fourier‐transform infrared spectroscopy bands and their functional groups for ZnO and CeO2 nanoparticles

| Absorption bands (cm−1) | Functional groups | Peak assigned | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3350‐3450 | N—H Band | CeO2 | 1, 2 |

| 2000‐3400 | O—H Stretching vibration of H2O | CeO2 | 3, 4 |

| 2330 | C—H stretching | CeO2 | 8 |

| 1529 | C—O asymmetric stretching (CeO2) | CeO2 | 10 |

| 1331 | Ce—O stretching vibrations | CeO2 | 9 |

| 484 | Ce—O stretching vibrations | CeO2 | 37 |

| 3426 | O—H stretching | ZnO | 36, 38 |

| 1628 | H—O—H bending vibration | ZnO | 36 |

| 1390 | C—H stretching vibration | ZnO | 38 |

| 852 | C—N stretching | ZnO | 38 |

| 401 | Zn—O stretching vibration | ZnO | 38 |

3.2. XRD diffraction analysis

The analysis of XRD can supply the formation of about the semi crystalline structure of chitosan, crystalline structure of chitosan‐ZnO and chitosan‐ZnO/CeO2 (Figure 2). The XRD structure of CS‐ZnO and CS shows the peak of diffraction at 2θ = 24° (phase of hydrate crystalline, form‐1) and the weak peak at 2θ = 16.5° (phase of hydrate crystalline, form‐2). The peaks that are observed in CS and CS‐ZnO wound healing materials were in better agreement with the hexagonal phase in the particles of ZnO (JCPDS file No: 36‐1451), and the reported results are in Reference 39. Figure 2C shows the powder diffraction of the chitosan‐CeO2/ZnO nanocomposites. The four major diffraction peaks at 2θ = 28.54°, 47.47°, 59.07° and 69.40° found in the diffraction patterns of CeO2 can be attributed to planes (111), (220), (222) and (400) possible for cubic structure of CeO2 (JCPDS file No: 81‐0792). 38 The presence of relatively sharp peaks with broad wave background suggests that the nanocomposite is in the semi crystalline status. The crystallite size was calculated from XRD studies using Scherrer's formula. The calculated values of crystallite size for the nano composites of CS‐ZnO/CeO2, CS‐ZnO and CS are 45, 37 and 22 nm, respectively.

FIGURE 2.

X‐ray diffraction diffraction pattern of A as chitosan (CS), B as chitosan‐ZnO (CS) and C as chitosan‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nanocomposites as wound dressing materials

3.3. UV‐vis spectral studies

The spectra of UV‐vis of the CS‐ZnO/CeO2, CS‐ZnO and CS samples are showed in Figure 3A‐C. CeO2 (pink) shows the absorption below 400 nm (3.10 eV) with an absorbance peak that is well‐defined at around 285 nm (4.35 eV). UV‐vis absorption spectra of the mixed phase with hexagonal phase ZnO (green) (chitosan‐ZnO) nanoparticles at 268 nm in good agreement with the data reported earlier. 38 The spectrum of UV‐vis of phase of hexagonal structure of the nano particles of ZnO in the concentrated HCl was seen in the region of 200‐800 nm. The absorption peak of the UV spectrum shows the value of 314 nm. The absorption peak at 314 nm is for the transition of valence‐to‐conduction band. The absorption peaks are corresponding to the transitions like n → π* and π → π*. 40

FIGURE 3.

UV‐vis spectra of A as chitosan (CS), B as chitosan‐ZnO (CS) and C as chitosan‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nanocomposites as wound dressing materials

3.4. Thermal studies

Figure 4A‐C shows the thermogravimetric analysis of hybrid nano composites of CS‐ZnO/CeO2, CS‐ZnO and CS. Moreover, it is reported previously that the neat CS displays the weight loss in two steps. Therefore, the Ca from the room temperature is 150°C, the weight loss is associated with evaporation of water and the temperature range is 170°C‐300°C, the weight loss is for the degradation the of CS. 41 The TGA curve of chitosan‐ZnO/CeO2 nanocomposite shows three stages of weight losses at 129°C, 444°C and 773°C. The first weight loss of about 26% may be due to the elimination of dopant (eg, HCl or H2SO4). The absence of such weight loss in the case of chitosan without any dopant confirms that this weight loss is due to the loss of dopant. The second weight loss of about 23% at 444°C originates from the decomposition of low‐molecular‐weight fragments of the polymer. The third stage around 773°C can be attributed to the thermal decomposition of polymer molecule main chains. There is a 2% weight loss observed initially may be for the loss of entrapped the molecules of the water in the matrix. Similar weight losses are observed in other two proportions. Among the three nanocomposites viz. chitosan (CS), chitosan‐ZnO and chitosan‐ZnO/CeO2. The last one, chitosan‐ZnO/CeO2, showed maximum thermal stability.

FIGURE 4.

Thermal properties of A as chitosan (CS), B as chitosan‐ZnO (CS) and C as chitosan‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nanocomposites as wound dressing materials

3.5. Surface morphology

Surface morphology of “CS” polymer, “CS‐ZnO” hybrid composite and “CS‐ZnO/CeO2” hybrid nano composites was shown in Figure 5A‐C. Scanning electron microscopy analysis showed the semi crystalline nature of macroporous structure of chitosan polymer as shown in Figure 5A. Prepared chitosan sample with 15% of zinc chloride solution was added to get resultant CS‐ZnO hybrid composites; it shows the flower‐like structure of ZnO was confirmed in CS‐ZnO (Figure 5B). The above hybrid composites with 15% of CeO2 nanoparticles were added to get finally CS‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nanocomposites; its shows the grain like a structure.

FIGURE 5.

Scanning electron microscopy images of A as chitosan (CS), B as chitosan‐ZnO (CS) and C as chitosan‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nanocomposites as wound dressing materials

3.6. Antibacterial activity

The antibacterial activity of the nano composites of CS‐ZnO/CeO2, CS‐ZnO and CS was tested against two pathogens bacteria “S. aureus” and “E. coli” shown in Figure 6A,B. Moreover, according to the research report, the direct application of the active hybrid nano composites at the surface of the wound could be neutralised or diffused rapidly. Also, the potential properties of the nano composites could be exhibited extensively, when the bioactive chitosan incorporated ZnO and CeO2 hybrid nanocomposites, films and nanofibre. Even in our study, bacterial activity of CS‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nano composites against all the microbes are found in the formation of the clear zone of the inhibition as shown in Figure 6C, and their values are included in Table 2. The metal oxide‐incorporated chitosan‐based hybrid nano composites is explained by the following mechanism. 39 Chitosan bactericidal properties are generated by the relation between the positive charge of chitosan and negative charge of cell wall of bacteria to create the cell wall lysis and produces the discharge of cytoplasmic, which origins to mortality of microorganism. In majority of caesarean surgical wound sites, the Gram‐positive bacteria like S. aureus and Streptococcus faecalis and the Gram‐negative bacteria like E. coli and Klebsiella pseudomonas can be associated. As per previous literature studies, the high antibactericidal property of ZnO/CeO2 can inhibit the proliferation activity of pathogens. In order to evaluate that efficacy of bimetal nanoparticles against S. aureus and E. coli, the CS‐ZnO‐CeO2‐based nano hybrid composite reveals excellent zone of inhibition. 42 The process of antibacterial and bactericidal is significantly improved for metal oxide‐chitosan hybrid nano composites owing for enhancing the behaviour of chelation in the hybrid surface with the cell of bacteria that immense to the maximum death rate of the bacteria.

FIGURE 6.

A, Antibacterial activity of chitosan (CS), chitosan‐ZnO (CS) and chitosan‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nanocomposites against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus pathogens, B, Zone of inhibition ratio against two E. coli and S. aureus and C, Bar chart for the Zone of inhibition for E. coli and P. aeruginosa

TABLE 2.

Antibacterial properties of control, CS, CS‐ZnO and CS‐ZnO/CeO2 nanocomposites against different bacterial strains

| Bacteria name | Sample name (zone of inhibition in cm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (1) | CS (2) | CS‐ZnO (3) | CS‐ZnO/CeO2 (4) | |

| (A) Escherichia coli | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 0.6 ± 0.04 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 3.7 ± 0.4 |

| (B) Staphylococcus aureus | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 0.4 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 3.1 ± 0.6 |

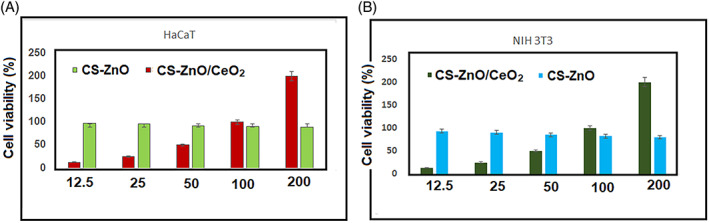

3.7. In vitro cell viability

The MTT assay revealed that the proliferative effect of CS‐ZnO/and CS‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nanocomposites on fibroblast tended to decrease by the addition of CeO2 in the hybrid nanocomposites as shown in Figure 7A,B. Brunner et al 43 and Chigurupati et al 44 suggested that CeO2 inhibits the proliferation of fibroblast (NIH 3T3) and keratinocyte (HaCaT) proliferation by generating ROS, leading to strong DNA damage. The anti‐proliferative and proliferative effect of CeO2 were attributed to its bilateral character which at low concentration can induce a decrease level in the intracellular ROS level. It was suggested that the expression of haeme oxygenase 1 and the cells get a temporary resistance to oxidative stress. In contrast, CS‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nanocomposites cause a dysfunction of anti‐oxidative systems and thus increase the level of ROS.

FIGURE 7.

Cell viability analysis of NIH 3T3 fibroblast and human keratinocytes (HaCaT) cell lines evaluated using MTT assay proliferation and adherence onto the chitosan‐ZnO/CeO2 nanocomposites as wound healing material at 24 hours

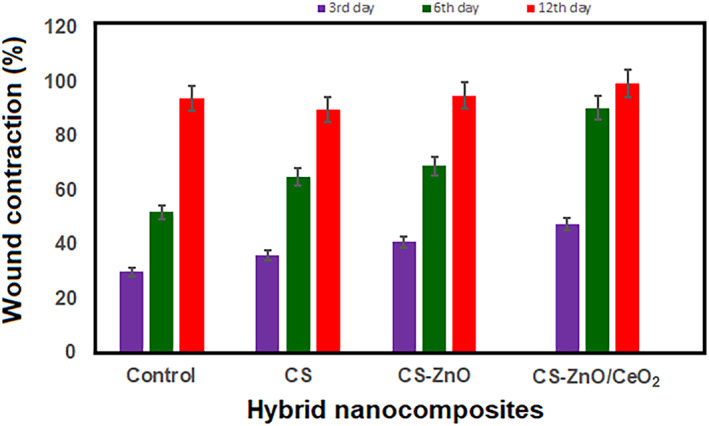

3.8. In vivo studies

Based on the results obtained from the earlier investigations, control, CS‐ZnO and CS‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nanocomposites were chosen for further investigations via in vivo studies. Figure 8 shows the macroscopic appearance of the wound sites treated with control (sterile gauze), CS‐ZnO and CS‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nanocomposites. The wound photographic evaluation indicates that there is no sign of inflammation or infections in any of the wounds. After 2 weeks, the control group were fresh, whereas the CS‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nanocomposite‐treated almost healed the same time. To quantify the wound healing process, the wound closure was determined in Figure 9. The chitosan‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nanocomposites dressing had the wound closure 95.40 and 98.90%, 3, 6 and 12 days post wound, respectively, and CS‐ZnO nanocomposites dressing had the wound closure 86% and 92% for the same day. These values were 18% and 65% for the control group at the end of the 3rd, 6th and 12th days, respectively. The wound closure percentage of CS‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nanocomposites was significantly higher than that of control group in each time interval. In the skin, the highest concentration of zinc‐based composites is found in the epidermis, especially in the keratinocytes closest to the basement membrane. In the initial inflammatory phase, zinc levels rise at the edges of the wound, and this concentration increases during granulation and epithelisation phase. This is due to increased expression of membrane transporters in keratinocytes, fibroblasts and macrophages. In the final stage of wound healing, these levels are reduced, with the consequent decrease in cell division.

FIGURE 8.

Photographic images of wound healing from same distance at different days

FIGURE 9.

Percentage of wound contraction of control, CS‐ZnO hybrid composite and CS‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nanocomposites, with mean ± SD (n = 4)

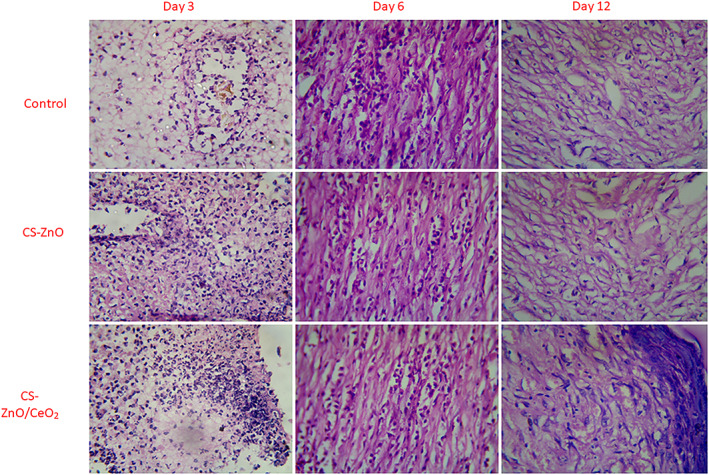

3.9. Histopathological studies

Histological examinations were helpful to provide insight into cellular mechanism of wound healing. It has been reported massive degradation of product of hybrid nanocomposites. In our case, CS‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nanocomposites could stimulate inflammatory cell aggregation and promote epithelial and vascular endothelial cells, which leads to significant wound heling rate of treated groups than control. Figure 10 exhibited H&E‐stained microscopic observations of wound site treated with prepared hybrid nanocomposites as dressing materials and control at day 3, 6 and 12, which would be described as more significant periods to healing mechanisms. As shown in Figure 10, stained tissues have presented more inflammatory infiltrates treated with CS‐ZnO and CS‐ZnO/CeO2 at day 6. At the same time, H&E‐staining parts of control (bare wound) have more inflammatory cells than CS‐ZnO and CS‐ZnO/CeO2 groups, which confirms that prepared hybrid nanocomposites have provided suitable biological environments for infiltrations of inflammatory cells at day 6. As observed, the group CS‐ZnO/CeO2 has large collagen content followed by CS‐ZnO‐treated group and control, on 12th day post operation. These findings indicate that the CS‐ZnO/CeO2 has facilitated the proliferation and migration of fibroblast and permitted the normal sequence of dynamic events of newly generated skin.

FIGURE 10.

H&E staining of control, CS‐ZnO hybrid composite and CS‐ZnO/CeO2 hybrid nanocomposites treated groups on day 0, 3, 6 and 12 after wound excision (magnification: ×40)

4. CONCLUSION

In this study, we prepared and examined the chitosan‐ZnO/CeO2 nanocomposites for the treatment of full wound thickness. Our results showed that the CS‐ZnO composites containing CeO2 nanoparticles exhibited the highest cell proliferation. In vivo study results supported the favourable wound healing effect of the CeO2 nanoparticles containing nanocomposites with accelerated wound healing compared with the sterile gauze. However, the chitosan polymer and nanocomposite based dressings must be considered due to excellent cell adhesion and antibacterial performances with macroporous structure. Therefore, our results provide evidence supporting the possible applicability of the CS‐ZnO/CeO2 nanocomposites containing wound dressing for successful wound treatment.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that this manuscript have no financial conflict of interest.

Gao Y, Wang X, Zhang Y, Li J, Zhang H, Li J. Novel fabrication of bi‐metal oxide hybrid nanocomposites for synergetic enhancement of in vivo healing and wound care after caesarean section surgery. Int Wound J. 2022;19(7):1705‐1716. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13771

Yan Gao and Xiaorui Wang contributed equally to this study.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kant V, Gopal A, Kumar D, et al. Topical pulmonic F‐127 gel application enhances cutaneous wound healing in rats. Acta Histochem. 2014;116:5‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dissemond J, Goos M, Wagner NS. The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis and therapy of chronic wounds. Hautarzt. 2002;53:718‐723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aneggi E, Boaro M, Leitenburg C d, Dolcetti G, Trovarelli A. Insights into the redox properties of ceria‐based oxides and their implications in catalysis. J Alloys Compd. 2006;408‐412:1096‐1102. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sun C, Li H, Chen L. Nanostructured ceria‐based materials: synthesis, properties, and applications. Energ Environ Sci. 2012;5:8475‐8505. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Montini T, Melchionna M, Monai M, Fornasiero P. Fundamentals and catalytic applications of CeO2‐based materials. Chem Rev. 2016;116:5987‐6041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dong H, Du SR, Zheng XY, et al. Lanthanide nanoparticles: from design toward bioimaging and therapy. Chem Rev. 2015;115:10725‐10815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hirst SM, Karakoti AS, Tyler RD, Sriranganathan N, Seal S, Reilly CM. Anti‐inflammatory properties of cerium oxide nanoparticles. Small. 2009;5:2848‐2856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kim CK, Kim T, Choi I‐Y, et al. Ceria nanoparticles that can protect against ischemic stroke. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:11039‐11043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heckman KL, DeCoteau W, Estevez A, et al. Custom cerium oxide nanoparticles protect against a free radical mediated autoimmune degenerative disease in the brain. ACS Nano. 2013;7:10582‐10596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Estevez AY, Pritchard S, Harper K, et al. Neuroprotective mechanisms of cerium oxide nanoparticles in a mouse hippocampal brain slice model of ischemia. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1155‐1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sudipta S, Das S, Cerium oxide nanoparticles and associated methods for promoting wound healing US Pat., US20130195927A1; 2013.

- 12. Ueno H, Mori T, Fujinaga T. Topical formulations and wound healing applications of chitosan. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;52:105‐115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Azad AK, Sermsintham N, Chandrkrachang S, Stevens WF. Chitosan membrane as a wound‐healing dressing: characterization and clinical application. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2004;69:216‐222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Leonida MD, Banjade S, Vo T, Anderle G, Haasand GJ, Philips N. Nanocomposite materials with antimicrobial activity based on chitosan. Int J Nano Biomater. 2011;3:316‐334. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ong S‐Y, Wu J, Moochhala SM, Tan M‐H, Lu J. Development of a chitosan‐based wound dressing with improved hemostatic and antimicrobial properties. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4323‐4332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li C, Fu R, Yu C, et al. Silver nanoparticle/chitosan oligosaccharide/poly(vinyl alcohol) nanofibers as wound dressings: a preclinical study Int J Nanomedicine, 2013;8:4131‐4145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liang D, Lu Z, Yang H, Gao J, Chen R. Novel asymmetric wettable AgNPs/chitosan wound dressing: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8:3958‐3968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Alavi M. Modifications of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC), nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), and nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) for antimicrobial and wound healing applications. e‐Polym. 2019;19:103. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Alavi M, Karimi N. Ultrasound assisted‐phytofabricated Fe3O4 NPs with antioxidant properties and antibacterial effects on growth, biofilm formation, and spreading ability of multidrug resistant bacteria. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2019;47(1):2405‐2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Alavi M, Karimi N, Salimikia I. Phytosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles and its antibacterial, antiquorum sensing, antimotility, and antioxidant capacities against multidrug resistant bacteria. J Ind Eng Chem. 2019;72:457‐473. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Alavi M, Karimi N, Valadbaeigi T. Antibacterial, antibiofilm, antiquorum sensing, antimotility, and antioxidant activities of green fabricated ag, cu, TiO2, ZnO, and Fe3O4 NPs via Protoparmeliopsis muralis lichen aqueous extract against multi‐drug‐resistant bacteria. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2019;5(9):4228‐4243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Black C, Kaye JA, Jick H. Cesarean delivery in the United Kingdom time trends in the general practice research database. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(1):151‐155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. Births: preliminary data for 2006. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2007;56:1‐18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Villar J, Valladares E, Wojdyla D, et al. WHO 2005 global survey on maternal and perinatal health research group. Lancet. 2006;367(9525):1819‐1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Hauth JC, Rouse DJ, Spong CY. Williams Obstetrics. 22nd ed., New York, NY: McGraw‐Hill; 2010:544‐545. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Al Busaidi I, Al‐Farsi Y, Ganguly S, Gowri V. Obstetric and non‐obstetric risk factors for cesarean section in Oman. Oman Med J. 2012;27(6):478‐481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Owen J, Andrews WW. Wound complications after cesarean sections. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1994;37(4):842‐855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Hauth JC, Rouse DJ, Spong CY. Williams Obstetrics. 22nd ed., New York, NY: McGraw‐Hill; 2010:665. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Magann EF, Chauhan SP, Rodts‐Palenik S, Bufkin L, Martin JN Jr, Morrison JC. Subcutaneous stitch closure versus subcutaneous drain to prevent wound disruption after cesarean delivery: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(6):1119‐1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mousavi SA, Mortazavi F, Chaman R, Khosravi A. Quality of life after cesarean and vaginal delivery. Oman Med J. 2013;28(4):245‐251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gunn B, Ali S, Abdo‐Rabbo A, Suleiman B. An investigation into perioperative antibiotic use during lower segment caesarean sections (LSCS) in four hospitals in Oman. Oman Med J. 2009;24(3):179‐183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sellappan LK, Anandhavelu S, Doble M, et al. Biopolymer film fabrication for skin mimetic tissue regenerative wound dressing applications. Int J Polym Mater Polym Biomater. 2020;71(3):196‐207. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sellappan L, Sanmugam A, Manoharan S. Fabrication of dual layered biocompatible herbal biopatch from biological waste for skin‐tissue regenerative applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;183:1106‐1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pandit AP, Koyate KR, Kedar AS, Mute VM. Spongy wound dressing of pectin/carboxymethyl tamarind seed polysaccharide loaded with moxifloxacin beads for effective wound heal. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;140:1106‐1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kumar SL, Anandhavelu S, Swathy M. Preparation and characterization of goat hoof keratin/gelatin/sodium alginate base biofilm for tissue engineering application. Integr Ferroelectr. 2019;202(1):1‐12. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kannan SK, Sundrarajan M. A green approach for the synthesis of a cerium oxide nanoparticle: characterization and antibacterial activity. Int J Nanosci. 2014;13(03):1450018. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Prabaharan DM, Sadaiyandi K, Mahendran M, Sagadevan S. Structural, optical, morphological and dielectric properties of cerium oxide nanoparticles. Mater Res. 2016;19(2):478‐482. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Farahmandjou M, Zarinkamar M, Firoozabadi TP. Synthesis of cerium oxide (CeO2) nanoparticles using simple CO‐precipitation method. Rev Mex Fis. 2016;62(5):496‐499. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Anandhavelu S, Thambidurai S. Preparation of chitosan–zinc oxide complex during chitin deacetylation. Carbohydr Polym. 2011;83:1565‐1569. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhang Q, Zhao X, Duan L, Shen H, Liu R. Controlling oxygen vacancies and enhanced visible light photocatalysis of CeO2/ZnO nanocomposites. J Photochem Photobiol A Biol. 2020;392(1):112156. [Google Scholar]

- 41. González‐Campos J, Prokhorov E, Bárcenas G, et al. Polylactide/exfoliated graphite nanocomposites with enhanced thermal stability, mechanical modulus, and electrical conductivity. J Polym Sci B Polym Phys. 2010;48:739‐748. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Munawar T, Mukhtar F, Nadeem MS, et al. Novel photocatalyst and antibacterial agent; direct dual Z‐scheme ZnO–CeO2‐Yb2O3 heterostructured nanocomposite. Solid State Sci. 2020;109:106446. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brunner TJ, Wick P, Manser P, et al. In vitro cytotoxicity of oxide nanoparticles: comparison to asbestos, silica, and the effect of particle solubility. Environ Sci Technol. 2006;40:4374‐4381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chigurupati S, Mughal MR, Okun E, et al. Effects of cerium oxide nanoparticles on the growth of keratinocytes, fibroblasts and vascular endothelial cells in cutaneous wound healing. Biomaterials. 2013;34:2194‐2201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable.