Abstract

No recombinant protein is available for serodiagnosis of melioidosis. In this study, we report the cloning of the groEL gene, which encodes an immunogenic protein of Burkholderia pseudomallei. Bidirectional DNA sequencing of groEL revealed that the gene contained a single open reading frame encoding 546 amino acid residues with a predicted molecular mass of 57.1 kDa. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool analysis showed that the putative protein encoded by groEL is homologous to the chaperonins encoded by the groEL genes of other bacteria. It has 98% amino acid identity with the GroEL of Burkholderia cepacia, 98% amino acid identity with the GroEL of Burkholderia vietnamiensis, and 82% amino acid identity with the GroEL of Bordetella pertussis. Furthermore, it was observed that patients with melioidosis develop a strong antibody response against GroEL, suggesting that the recombinant protein and its monoclonal antibody may be useful for serodiagnosis in patients with melioidosis and that the protein may represent a good cell surface target for host humoral immunity. Further studies in these directions would be warranted.

Melioidosis is a serious human disease, endemic in Southeast Asia, caused by the bacterium Burkholderia pseudomallei. B. pseudomallei is a natural saprophyte that can be isolated from soil, stagnant streams, rice paddies, and ponds, which are the major natural reservoirs of the bacteria (13). Although melioidosis is endemic in Southeast Asia, human infections have occurred throughout the world between 20° north and south latitudes (10). B. pseudomallei is very different from other nonfermentative gram-negative bacteria in terms of the spectrum of disease that it can cause. Illness can be manifested as an acute, subacute, or chronic process. Moreover, the incubation period of melioidosis can vary from 2 days to 26 years (15).

No recombinant antigen-based serological tests or vaccines are available for B. pseudomallei infections. Definitive diagnosis of melioidosis still depends on the isolation and identification of B. pseudomallei from blood, sputum, pus, swabs, and other clinical specimens. However, the number of B. pseudomallei organisms in clinical specimens collected from nonbacteremic patients is often low compared to those in infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus, enterobacteria, and anaerobes. Furthermore, laboratory identification is often delayed because many laboratory personnel are unfamiliar with the bacterium, and B. pseudomallei may be misclassified as “Pseudomonas sp.” (14). Therefore, serological tests have been investigated to show the antibody response of patients in the diagnosis of melioidosis. These include indirect hemagglutination assay (IHA), complement fixation assay, indirect immunofluorescent assay, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA); IHA and ELISA have been the most commonly used methods (4, 17, 23, 24). However, IHA is observer biased, and a 16-fold variation in serological titer is not uncommon due to the variability of the lipopolysaccharide antigen coating on red cells. Recently, it has been shown that ELISA using lipopolysaccharide is superior to IHA in both sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of melioidosis (17). However, no antibody detection kit based on recombinant antigens of B. pseudomallei is commercially available at present. Antibody detection tests using recombinant antigens are easier to standardize and may offer higher sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility. As for vaccination, although it has been suggested that flagellin protein, endotoxin-derived O-polysaccharide antigens, capsular polysaccharide, attenuated strains of B. pseudomallei, and recombinant culture of Francisella tularensis carrying a plasmid with fragments of B. pseudomallei chromosome may be good candidates (5, 12), none of these have been proved to be clinically useful for the prevention of melioidosis.

In this study, we report the cloning of the groEL gene, which encodes an immunogenic protein of B. pseudomallei. DNA sequence analysis reveals that the B. pseudomallei groEL gene has an open reading frame encoding 546 amino acid residues. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) analysis shows that the putative protein is highly homologous to the GroEL proteins of other bacteria. Finally, our results show that patients with melioidosis develop high levels of specific antibody against GroEL, suggesting that GroEL may represent a good target for the development of vaccines for melioidosis.

The B. pseudomallei strain used was isolated from the blood culture of a patient suffering from acute septicemic melioidosis in 1998. The bacterium was grown on blood agar plates at 37°C to obtain single bacterial colonies, which were then cultured in Trypticase soy broth at 37°C for 24 h.

Total genomic DNA was obtained from 100 ml of culture of B. pseudomallei according to the standard protocol (1). The genomic DNA was partially digested with Sau3A (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany). The partial digest with fragments of 1.5 to 6 kb were then ligated to the BamHI site of the vector provided by the ZAP Express vector kit (Strategene, La Jolla, Calif.), and a phage expression library was constructed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The library had at least 1 million independent phage plaques, with more than 95% containing inserts of an average size of 2.3 kb, as checked by restriction enzyme digestion of 100 clones with SalI and XbaI (Boehringer Mannheim).

Approximately 50,000 plaques of this library were screened with serum obtained from a patient with culture-documented melioidosis according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the library was plated on NZY plates at 5,000 PFU per plate with 600 μl of XL1-Blue cells at an optical density at 600 nm of 0.5 and 6.5 ml of NZY top agar. The plates were incubated at 42°C for 6 h and at 37°C for 4 h. The proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After being blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 7% skim milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the membranes were incubated with serum obtained from a patient with culture-documented melioidosis at a 1:2,000 dilution at 25°C for 1 h. After being washed with 3% BSA in PBS three times, the membranes were incubated with rabbit anti-human antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Zymed Laboratories Inc., South San Francisco, Calif.) at 1:5,000 dilution at 25°C for 1 h. After being washed with 3% BSA in PBS three times, antigen-antibody interaction was detected with the ECL fluorescence kit (Amersham Life Science, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). Twenty-four positive phage clones were isolated, and their DNA inserts were excised with ExAssist helper phage in SOLR cells, yielding pBK-CMV plasmids containing the inserts.

Overnight cultures of SOLR cells with pBK-CMV and SOLR cells with pBK-CMV-GroEL were induced with 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 4 h. The cells were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 5 min and resuspended in PBS with 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 and 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The cells were sonicated three times (10 s each time). Twenty-five microliters of the cell extracts obtained were electrophoresed on a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–10% polyacrylamide gel and electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). The blot was incubated with a 1:2,000 dilution of the serum used for library screening and serum of a normal blood donor using 5% skim milk in PBS with 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20 as the blocking buffer, and antigen-antibody interaction was detected with the ECL fluorescence kit.

DNA sequencing was carried out by using vector primers of pBK-CMV (T3 and T7) and synthetic primers designed from the sequencing data of the first and second rounds of the sequencing reaction (LPW124, 5′-CGGCAAGGAAGGCGTGAT-3′; LPW134, 5′-CGCACGCAAATCGAAGAA-3′; LPW136, 5′-GATCGCCGCACTGCTCGC-3′; and LPW125, 5′-GCTACACGGTGCGCGACT-3′). Bidirectional DNA sequencing was performed with an ABI automatic sequencer (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.) according to the manufacturers' instructions (21). The DNA sequence was analyzed by BLAST search with the National Center for Biotechnology Information server at the National Library of Medicine (Bethesda, Md.). The searches were performed at both the protein and DNA levels. Phylogenetic-tree construction was performed by the Clustal method with MegAlign 4.00 (DNAstar Inc., Madison, Wis.).

To produce a fusion plasmid for protein purification, the sequence coding for amino acid residues 1 to 546 of GroEL was amplified by PCR using the pBK-CMV-GroEL plasmid as a template. The pBK-CMV-GroEL plasmid was amplified with 0.5 μM primers (LPW127, 5′-GGAATTCCTTACATGTCCATGCCCATG-3′, and LPW144, 5′-CGGGATCCCGATGGCAGCTAAAGACGT-3′) (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.). The PCR mixture (50 μl) contained pBK-CMV-GroEL, PCR buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.01% gelatin), 200 μM (each), deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 1.0 U of Taq polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim). The mixtures were amplified in 40 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min, and 68°C for 2 min and a final extension at 68°C for 10 min in an automated thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Gouda, The Netherlands). The amplified fragment was cloned into the BamHI and EcoRI sites of expression vector pGEX-5X-3 in frame and downstream of the glutathione S-transferase (GST) coding sequence. The GST-GroEL fusion protein was expressed and purified with the GST gene fusion system (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) according to the manufacturer's instructions (3). Approximately 2.5 mg of highly purified GST-GroEL fusion protein was routinely obtained from 1 liter of Escherichia coli carrying the fusion plasmid.

Highly purified GST-GroEL fusion protein samples were run on an SDS–10% polyacrylamide gel (35 μg per lane) and electroblotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). The blot was incubated with a 1:2,000 dilution of sera from three patients with culture-documented melioidosis, two patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia, two patients with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia bacteremia, one patient with Acinetobacter baumanii bacteremia, or healthy blood donors, and antigen-antibody interaction was detected as described above. All sera were collected from patients during acute illness.

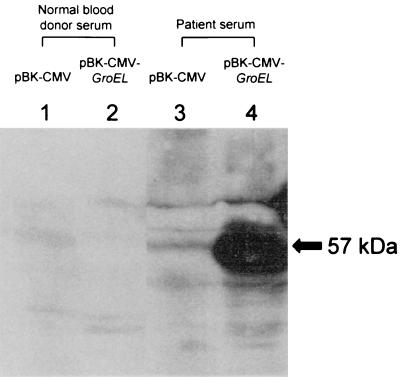

About 50,000 independent phage plaques were screened with the serum obtained from a patient with melioidosis. Twenty-four positive plaques were selected, purified, and converted into plasmids. When induced with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside, 2 of the 24 isolates produced protein bands of about 57 kDa that were recognized by the serum from a patient with melioidosis on a Western blot (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Western blot analysis of GroEL of B. pseudomallei. Shown are cell extracts of overnight cultures of SOLR cells with pBK-CMV (lanes 1 and 3) and SOLR cells with pBK-CMV-GroEL (lanes 2 and 4) electrophoresed on an SDS–10% polyacrylamide gel. Antigen-antibody interaction was detected with the serum of a patient with melioidosis (lane 4) but not with the serum of a healthy blood donor (lane 2).

Bidirectional DNA sequencing of the insert revealed that the DNA contained a single open reading frame of 1,638 bp, encoding 546 amino acid residues with a predicted molecular mass of 57.1 kDa.

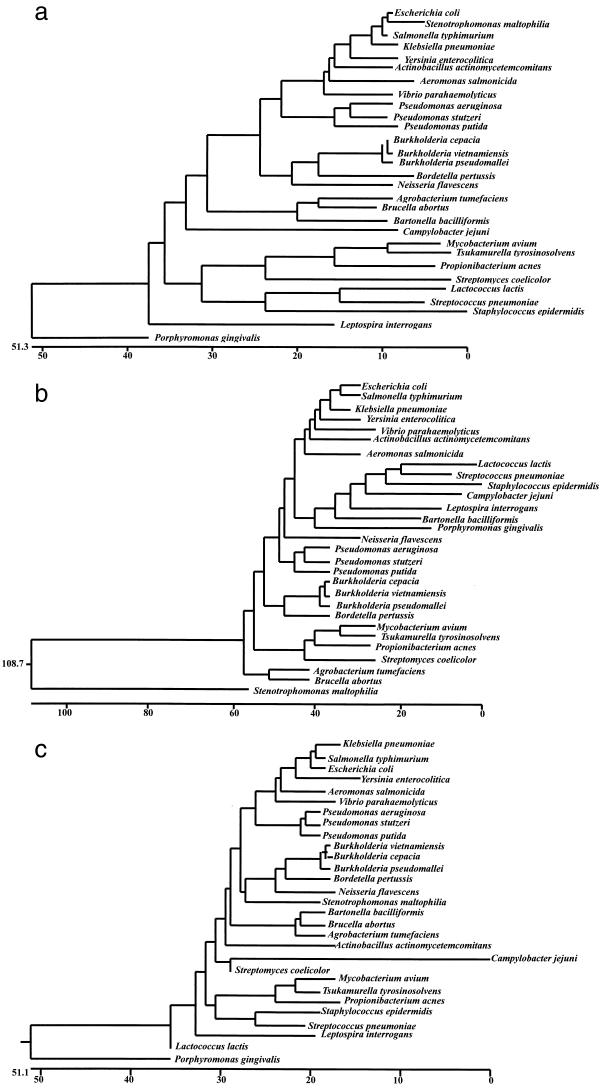

BLAST analysis was performed to search for homologs that might suggest potential biological functions. It revealed that the putative protein encoded by the gene is homologous to the GroEL proteins of other bacteria (Fig. 2a). It has 98% amino acid identity with the GroEL of Burkholderia cepacia (GenBank accession no. AF104907), 98% amino acid identity with the GroEL of Burkholderia vietnamiensis (GenBank accession no. AF104908), and 82% amino acid identity with the GroEL of Bordetella pertussis (GenBank accession no. U12277). The gene was named groEL of B. pseudomallei.

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic trees based on known bacterial GroEL amino acid sequences (a), nucleotide sequences (b), and their corresponding 16S rRNA gene sequences (c) illustrating the position of B. pseudomallei.

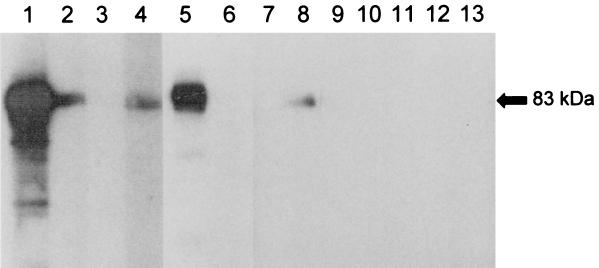

Strong antigen-antibody interaction was detected with the sera of three patients with melioidosis, none of whom had a past history of Burkholderia infection (Fig. 3, lanes 1, 2, and 5). Weaker antigen-antibody interaction was detected with the sera of one patient with P. aeruginosa bacteremia (Fig. 3, lane 4) and one patient with S. maltophilia bacteremia (Fig. 3, lane 8). No antigen-antibody interaction was detected with the sera of one patient with A. baumanii bacteremia (Fig. 3, lane 6), one patient with P. aeruginosa bacteremia (Fig. 3, lane 3), one patient with S. maltophilia bacteremia (Fig. 3, lane 7), and all five healthy blood donors (Fig. 3, lanes 9 to 13).

FIG. 3.

Western blot analysis of purified GST-GroEL of B. pseudomallei. Strong antigen-antibody interaction was detected with the sera of three patients with melioidosis (lanes 1, 2, and 5). Weaker antigen-antibody interaction was detected with the sera of one patient with P. aeruginosa bacteremia (lane 4) and one patient with S. maltophilia bacteremia (lane 8). No antigen-antibody interaction was detected with the sera of one patient with A. baumanii bacteremia (lane 6), one patient with P. aeruginosa bacteremia (lane 3), one patient with S. maltophilia bacteremia (lane 7), and all five healthy blood donors (lanes 9 to 13).

Chaperonins are large protein complexes that assist protein folding in vivo. Although protein folding is often regarded as a spontaneous, thermodynamically stable process in vitro, the folding of polypeptide chains in vivo is often faced with adverse conditions, with high protein concentration and temperature that favor strong intermolecular hydrophobic interactions, leading to protein misfolding and aggregation. Therefore, chaperonins are essential to assist this last step of the information transfer pathway from genes to functional proteins (7, 9). Chaperonins have been identified in all three domains of life: Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya (including cytosolic chaperonins, as well as chaperonins in endosymbiotically derived organelles, such as mitochondria and chloroplasts) (6, 8). By comparing their nucleotide and amino acid sequences, chaperonins are classified into two groups: group I, which includes members from bacteria (GroEL), mitochondria (Hsp60), and chloroplasts (Rubisco binding protein), and group II, which includes members from archaea and the cytosol of eukaryotes (20, 22).

The amino acid sequence of GroEL of B. pseudomallei resembles those of other gram-negative bacteria, especially the nonfermentative gram-negative bacteria, and other Burkholderia species. It is interesting to note that the phylogenetic tree based on the amino acid sequences of the GroEL proteins in various bacteria (Fig. 2a) resembles the phylogenetic tree of the 16S rRNA gene sequences of the corresponding bacteria (Fig. 2c) more than the tree based on the nucleotide sequences of the groEL genes of the bacteria (Fig. 2b). From Fig. 2, it can be observed that the nucleotide sequence of groEL of Neisseria flavescens is more distantly related to those of the Burkholderia species and B. pertussis, but the corresponding amino acid sequences and 16S rRNA gene sequences of these bacteria are very closely related. Furthermore, the amino acid sequences and 16S rRNA gene sequences of groEL of Leptospira interrogens and Porphyromonas gingivalis are very distantly related to the other bacteria, but the corresponding nucleotide sequences of these two bacteria are more closely related to the other species in the phylogenetic trees. We speculate that the divergence of the tree based on groEL nucleotide sequences could be a result of codon usage bias of the various bacteria during evolution, which is due to a purifying selection governed by the relative abundance of the isoaccepting tRNA, as well as a biased mutation pressure due to the different GC contents, in the various bacteria (11, 18).

The cloning of groEL may have direct implications for laboratory diagnosis of B. pseudomallei infections. Since cystic fibrosis is very rare in southeast Asia, B. cepacia (whose GroEL showed 98% amino acid identify with that of B. pseudomallei) is not commonly found. Although cross-reactivity was shown in the sera of patients with P. aeruginosa and S. maltophilia bacteremias, the intensities of the bands were much lower than that in the sera of patients with melioidosis. As clinical diagnosis of melioidosis is often difficult because most patients present with fever without localizing signs and the number of bacteria in clinical specimens obtained from nonbacteremic patients is often low and the organism is often misidentified, the presence of a high level of antibody response in the absence of bacteremia due to other organisms and specific clinical features may suggest the diagnosis of melioidosis. An ELISA using purified GroEL should be further evaluated in a prospective clinical study for the serodiagnosis of melioidosis. In such a study, more sera from patients with P. aeruginosa, S. maltophilia, other Burkholderia species, and B. pertussis infections should be included.

Besides laboratory diagnosis, the GroEL protein can be used for immunization in those patients at high risk of developing B. pseudomallei infections. Chaperonins are immunodominant proteins in microbial infections, and GroEL has been investigated for use in vaccination against bacterial infections such as tuberculosis, brucellosis, and yersiniosis (2, 16, 19). From our results, the GroEL of B. pseudomallei was further shown to be closely associated with humoral immunity. Since B. pseudomallei is acquired by inhalation of infectious droplets, immunization could be administered through the mucosal route to stimulate the production of secretory immunoglobulin A, which is important for its neutralizing and complement activation activities. Whether GroEL is a good T-cell target remains to be tested, as cellular immune response would be equally important for defense against melioidosis, especially in patients with the chronic granulomatous types of presentations that resemble tuberculosis.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the groEL gene of B. pseudomallei has been deposited with GenBank under accession no. AF287633.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by the Committee of Research and Conference Grants, The University of Hong Kong.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N. Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1998. pp. 2.4.1–2.4.2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bae J E, Toth T E. Cloning and kinetics of expression of Brucella abortus heat shock proteins by baculovirus recombinants. Vet Microbiol. 2000;75:199–204. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(00)00203-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao L, Chan C M, Lee C, Wong S S, Yuen K Y. MPI encodes an abundant and highly antigenic cell wall mannoprotein in the pathogenic fungus Penicillium marneffei. Infect Immun. 1998;66:966–973. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.966-973.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charoenwong P, Lumbiganon P, Puapermpoonsiri S. The prevalence of the indirect hemagglutination test for melioidosis in children in an endemic area. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1992;23:698–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charuchaimontri C, Suputtamongkol Y, Nilakul C, Chaowagul W, Chetchotisakd P, Lertpatanasuwun N, Intaranongpai S, Brett P J, Woods D E. Antilipopolysaccharide II: an antibody protective against fatal melioidosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:813–818. doi: 10.1086/520441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellis R J. The chaperonins. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fayet O, Ziegelhoffer T, Georgopoulos C. The GroES and GroEL heat shock gene products of Escherichia coli are essential for bacterial growth at all temperatures. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:1379–1385. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.3.1379-1385.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartl F U. Molecular chaperones in cellular protein folding. Nature. 1996;381:571–579. doi: 10.1038/381571a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horwich A L, Low K B, Fenton W A, Hirshfield I N, Furtak K. Folding in vivo of bacterial cytoplasmic proteins: role of GroEL. Cell. 1993;74:909–917. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90470-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howe C, Sampath A, Spotnitz M. The pseudomallei group: a review. J Infect Dis. 1971;24:598. doi: 10.1093/infdis/124.6.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikemura T. Correlation between the abundance of Escherichia coli transfer RNAs and the occurrence of the respective codons in its protein genes. J Mol Biol. 1981;146:1–21. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iliukhin V I, Kislichkin N N, Merinova L K, Riapis L A, Denisov I I, Farber S M, Kislichkina O I. The outlook for the development of live vaccines for the prevention of melioidosis. Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 1999;3:52–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanaphun P, Thirawattanasuk N, Suputtamonkol Y, Naigowit P, Dance D A, Smith M D, White N J. Serology and carriage of Pseudomonas pseudomallei: prospective study in 1000 hospitalized children in northeast Thailand. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:230–233. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.1.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leelarasamee A, Bovornkitti S. Melioidosis: review and update. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:413–425. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mays E E, Rickets E A. Melioidosis: recrudescence associated with bronchogenic carcinoma twenty-six years following initial geographic exposure. Chest. 1975;68:261. doi: 10.1378/chest.68.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noll A, Autenrieth I B. Yersinia-hsp60-reactive T cells are efficiently stimulated by peptides of 12 and 13 amino acid residues in a MHC class II (I-Ab)-restricted manner. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;105:231–237. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-758.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petkanjanapong V, Naigowit P, Kondo E, Kanai K. Use of endotoxin antigens in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the diagnosis of P. pseudomallei infections (melioidosis) Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 1992;10:145–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sueoka N. On the genetic basis of variation and heterogeneity of DNA base composition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1962;48:582–592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.48.4.582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tascon R E, Colston M J, Ragno S, Stavropoulos E, Gregory D, Lowrie D B. Vaccination against tuberculosis by DNA injection. Nat Med. 1996;2:888–892. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trent J D, Nimmesgern E, Wall J S, Hartl F U, Horwich A L. A molecular chaperone from a thermophilic archaebacterium is related to the eukaryotic protein t-complex polypeptide-1. Nature. 1991;354:490–493. doi: 10.1038/354490a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woo P C Y, Leung P K L, Tsoi H W, Yuen K Y. Cloning and characterization of malE in Burkholderia pseudomallei. J Med Microbiol. 2001;50:330–338. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-50-4-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yaffe M B, Farr G W, Miklos D, Horwich A L, Sternlicht M L, Sternlicht H. TCP1 complex is a molecular chaperone in tubulin biogenesis. Nature. 1992;358:245–248. doi: 10.1038/358245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yap E H, Chan Y C, Ti T Y, Thong T W, Tan A L, Yeo M, Ho L C, Singh M. Serodiagnosis of melioidosis in Singapore by the indirect haemagglutination test. Singapore Med J. 1991;32:211–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zysk G, Splettstosser W D, Neubauer H. A review on melioidosis with special respect on molecular and immunological diagnostic techniques. Clin Lab. 2000;46:119–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]