Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) methods have been and are now being increasingly integrated in prediction software implemented in bioinformatics and its glycoscience branch known as glycoinformatics. AI techniques have evolved in the past decades, and their applications in glycoscience are not yet widespread. This limited use is partly explained by the peculiarities of glyco-data that are notoriously hard to produce and analyze. Nonetheless, as time goes, the accumulation of glycomics, glycoproteomics, and glycan-binding data has reached a point where even the most recent deep learning methods can provide predictors with good performance. We discuss the historical development of the application of various AI methods in the broader field of glycoinformatics. A particular focus is placed on shining a light on challenges in glyco-data handling, contextualized by lessons learnt from related disciplines. Ending on the discussion of state-of-the-art deep learning approaches in glycoinformatics, we also envision the future of glycoinformatics, including development that need to occur in order to truly unleash the capabilities of glycoscience in the systems biology era.

1. Introduction

Glycoinformatics, sometimes also called glycobioinformatics,1 can be straightforwardly defined as the application of bioinformatics to glycoscience. Bioinformatics, according to Wikipedia, refers to the creation and advancement of databases, algorithms, computational and statistical techniques, and theory to solve formal and practical problems arising from the management and analysis of biological data [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bioinformatics]. With the rise of systems biology and the expansion of -omics technologies, bioinformatics has become an integral part of research in life science.

The sheer size of experimental -omics data sets has grounded bioinformatics into data science. In recent years, emphasis has been put on the generation of findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR) biological data.2 Findable is indispensable, because data search is a frequent task that should obviously be made easy to the largest community of life scientists. However, as simple as this task seems, it still primarily requires that data and related metadata (information supplementing data) be associated with a unique and persistent identifier and, secondarily, readability by both humans and computers. Accessible is highly practical because it involves retrieval using these identifiers with a standardized protocol such as hypertext transfer protocol (HTTP). Interoperable is a crucial constraint in attempts to merge or integrate data from different sources. To become interoperable, data need to be described with standard languages reflecting knowledge representations, commonly known as ontologies, otherwise also qualified as controlled vocabularies. For example, gene ontology3 has revolutionized biomolecular data annotation and enabled rational cross-referencing between data resources. The first three FAIR principles precede the fourth, which ultimately is the goal of these efforts for data sustainability. Reusability can finally be achieved through well-described metadata, including data provenance and community standards. In the end, FAIRness rights to reuse data can be regulated by licensing but FAIR/O cancels any possible limitation and allows for free data reuse and open science. The surge of data generation, sharing, and usage in the recent SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is a good example of application of FAIR principles for everyone’s benefit.

Large volumes of consistent data are the ideal input for developing models and methods to predict a biological outcome. Myriads of solutions to predicting molecular shapes/structures, locations, expressions, as well as interactions populate bioinformatics toolboxes. A significant proportion of them rely on artificial intelligence (AI), mostly learning methods. Nonetheless, to achieve robustness and accuracy, these tools require not only quality data but also fine-tuning over time. A striking example is the prediction of protein 3D structure from sequence. Most learning approaches predicting structure from sequence leverage evolutionary information (e.g., via multiple sequence alignments) and/or existing structural information from homologous proteins. Neural networks were actually first used in the late 1980s to predict protein secondary structure from sequence,4 but the application of such AI-based prediction to 3D structure was delayed for over a decade. Early implementations relied on the prediction of amino acid contact maps,5 and, again, it took over another decade to bring this approach to the next level with RaptorX-Contact.6 Such progress was easy to follow through the critical assessment of protein structure prediction (CASP) competition designed to assess the quality of 3D structure prediction tools every second year since 1994 [https://predictioncenter.org/]. RaptorX-Contact used residual convolutional neural networks to predict contact maps from evolutionary coupling and sequence conservation with superior results on CASP11, the 2014 edition. This paved the way to AlphaFold27 that outshined CASP14, the 2020 edition, with further improvements and fined-tuned deep learning-based methods. AlphaFold2 predictions are increasingly accessible to users of major bioinformatics reference databases and portals (e.g., UniProt8), or to experienced bioinformaticians using community implementations (e.g., ColabFold9). In a nutshell and unsurprisingly, decades were needed to reach such excellence.

As a subset of bioinformatics, glycoinformatics faces similar challenges. Glyco-data, much like broad biological data, are spread across biology and chemistry, yet the complexity and the diversity of carbohydrate molecules, as well as their nontemplate driven biosynthesis, have created a wider gap between the two fields.

Carbohydrate chemistry research has been internationally coordinated for many decades through the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), of which it became an associated organization in 1970 [https://ico.chemistry.unimelb.edu.au/]. This age-old grounding in international exchange prompted the need for collecting data which eventually happened in the form of CarbBank,10 setting the premises of glycoinformatics at a time when bioinformatics was in its infancy. Unfortunately, the path to expansion was rough and long before the field was recognized, as reported in several reviews11−14 and a dedicated chapter in a reference manual,15 and despite the hurdles and various intermediary short-lived initiatives for collecting and storing glycan structural data, these have now found a safer place in the universal repository named GlyTouCan, first released in 2016 and hosted in Japan.16−18

In parallel, glycobiologists have concentrated their effort on multiple forms of functional studies to reveal that glycosylation is site-specific,19 tissue-dependent,20 and influenced by environment.21 Glycomics and glycoproteomics have matured to provide increasingly comprehensive data sets22 that have just begun to populate databases.23 Furthermore, the development of array technology, starting with the Consortium for Functional Glycomics (CFG) initiative, channelled screening data into a single location [http://www.functionalglycomics.org/glycomics/publicdata/home.jsp].

Up to this point in this Introduction, it appears that carbohydrate chemists determine the structural pieces of the puzzle while glycobiologists attempt to place them into a biological context. Yet biochemists hold another key with the elucidation of carbohydrate metabolism and catabolism. Bridging information provided by these different views is challenging. The attachment of solved structures on their conjugate(s) is often unspecified, and the correlation between a set of structures and their biosynthetic pathways is not obvious because chronology may be hard to establish and glycosyltransferase availability is frequently unknown. Quantitative evidence can be sought in transcriptome analyses that can shed light on the expression of carbohydrate biosynthetic enzymes that is notoriously different in distinct tissues, cell types, or diseases. Additional structural constraints can be determined because protein glycosylation is mainly regulated at the level of both the enzymatic machinery and the glycoprotein structure.24 Nonetheless, glycan-binding experiments are centered on ligands independent of their natural occurrence, making it difficult to reconcile all viewpoints. This situation is clearly presented in a recently published comprehensive overview25 that will not be reproduced or paraphrased here. Rather, the present review extends this prior description of the glycoinformatics landscape with a focus on learning methods and their applications in glycobiology. To do so, we briefly survey the specificity of glyco-data in the life science data ecosystem as well as the long-standing presence of AI methods in bioinformatics and glycoinformatics. The two aspects, data and AI, are tightly interrelated as exposed throughout this review. Importantly, AI methods are data hungry, and, unavoidably, our coverage is therefore biased toward the most abundantly generated glyco-data, which tends to be related to glycans in association with glycoproteins (N-/O-linked) and, to a lesser extent, glycan-binding proteins. This panorama is followed by a focus on the spreading of deep learning approaches in glycoscience. Finally, we summarize our view of future development in AI-based applications in this context.

2. Idiosyncrasies of Experimental Data in Glycoscience

Any prediction or modeling tool requires data processing, and the more precise the definition of the possible solution space, the better the tool will perform. Recalling the fragmented situation presented in the introduction, glycoscience data have unique features that need to be considered.

2.1. Sparsity

At this point in time, the estimate of the “glycan space” dimension is controversial and reminiscent of the debated estimate of the human genome content prior to sequencing it. Speculation about the gene count ranged between 30 000 and 500 000, and actual data forced everyone into a more or less drastic downscaling. Our current knowledge of glycan biosynthesis makes it difficult to set boundaries. In theory, there could be billions of structures considering all known species, but, practically, GlyTouCan currently contains close to ∼51 000 structures (version 3.1.0), many of which are redundant due to varying degrees of resolution. Considering one species at a time, Homo sapiens is probably the most studied and the figures are not any more precise. At present, the range is often suggested to be on the order of magnitude of 104 and it is not clear whether the array of experimental techniques used to solve structures guarantees an exhaustive coverage of glycan structures. In fact, the regular occurrence of paradigm-shifting discoveries of a new glycan type with unconventional strategies tends to suggest that “standard” workflows may miss unexpected structures. The latest examples have revealed bisecting Lewis X structures in the human brain26 and even to-be-confirmed glycosylated RNA.27 Additionally, the attention of researchers is predominantly focused on protein-associated N- and O-linked glycans, with less consideration for glycolipids, which is even worse for glycosaminoglycans, lipopolysaccharides, or polymeric glycans. Reasons for this can be seen in the lack of accessible, large-scale, and comprehensive methods to study these molecules as well as their intrinsically higher heterogeneity. In a nutshell, the extent of the glycome remains a very open question. In this situation, data can be qualified as sparse because of their uneven spread in the glycan space. Specifically, the sparsity stems from at least two main sources: (i) the fraction of glycans yet unknown to us in any given species and (ii) the fraction of glycans that is not being measured (or cannot be annotated) in glycomics experiments due to sample processing, low abundance, ionization difficulties, isomers, and many other potential issues. Now, if we consider the estimate of 104 total human glycans, the pool of currently known human glycans can be placed somewhere around 3000, while a typical glycomics experiment merely measures dozens to low hundreds of glycans. Both types of sparsity are not only substantial but also due to systematic biases, some of which are mentioned above, making a systems perspective more difficult.

2.2. Heterogeneity

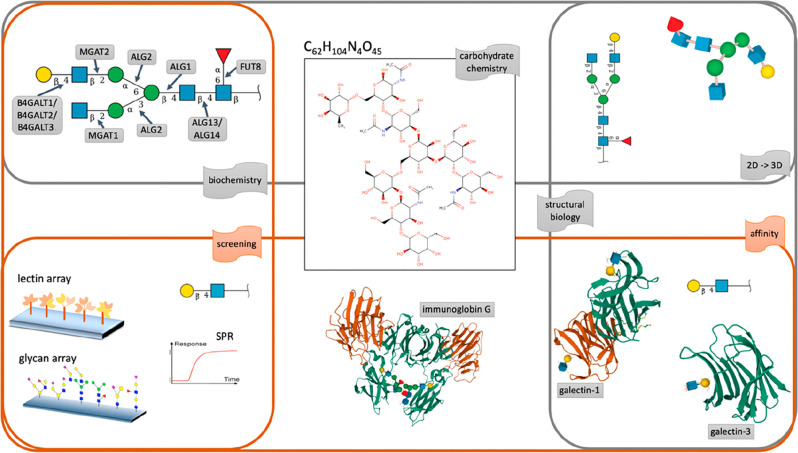

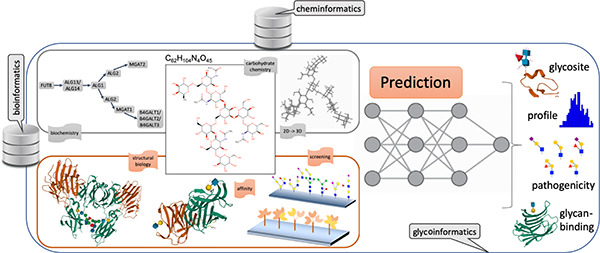

As mentioned earlier, the full qualification of the structure and the function of a glycan usually requires a set of experiments spanning chemistry, biochemistry, affinity, and screening technologies that are diverse and the results of which are difficult to corroborate. The situation is illustrated in Figure 1, where the various ways of collecting information on Gal(β1-4)GlcNAc(β1-2)Man(α1-6)[GlcNAc(β1–2)Man(α1-3)]Man(β1-4)GlcNAc(β1-4)[Fuc(α1-6)]β-GlcNAc are highlighted. In each case, the nature of the information and its extraction entails substantially different means, resulting in challenging matching and adjustment tasks in order to rationalize the presence of the glycan in the conditions where it was observed.

Figure 1.

Summary of information collectable from the structure of the C62H104N4O45compound, reflecting the diversity of questions addressed in glycoscience. Whether information is chemical (upper center), biochemical (upper left), and structural (upper right), it requires functional complements dependent on affinity or screening methods. In this example, C62H104N4O45 is shown to be attached to an immunoglobulin γ (lower center) and its terminal N-acetyllactosamine moiety recognized by galectin 1 and 3 (lower right) and possibly screened with array technologies (lower left).

Many techniques used in glycoscience require a compromise between efficiency (breadth) and precision (depth), especially in the high-throughput era. Mass spectrometry (MS) will be preferred to nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) if the experiment entails minimizing the sample load and maximizing the throughput, but it is likely to lower the level of structural details. This aspect as well as further details of glycan structural data acquisition are extensively covered in two recent reviews.28,29 For our purposes, suffice to say that distinguishing mass isomers is challenged by the multiplicity of commonly occurring monosaccharides such as hexoses present in the form of equally measurable glucose, mannose, or galactose, with the same chemical composition and mass. Here, various techniques such as digestion by monosaccharide-specific exoglycosidases or further fragmentation with mass spectrometry (MS2 to MSn) may result in less ambiguous identification. Likewise, glycomics MS data usually provide quality structural data but no protein site-specific information, while glycoproteomics MS data are precise on mapping glyco-sites but only with low resolution glycan compositions. In the end, the various sources are difficult to merge into a single and clear view of a glycome.

2.3. Field-Specific Encoding

The complications involved in determining a full glycome have two immediate consequences. Generally, the required time and expertise prevent glycoscientists from venturing into any other related-omic field. In turn, life scientists with no training in glycoscience are often disinclined to undertake sizable extra work to investigate glycosylation. In the end, a partial disconnection with biology tends to characterize the production of glyco-data.

From a bioinformatics point of view, the divide also exists. In the past decade, the mapping of metabolic pathways from genomes has brought cheminformatics closer to bioinformatics. This entails sharing data formats to promote data exchange so that reactions can be precisely described,30,31 with unambiguous substrates and products as well as definite enzymes initially translated from genomic sequences. All chemical compounds of the reference PubChem32 and ChEBI33 databases are described with SMILES34 and InChi/InChi Key35 encodings that are readable by the vast majority of cheminformatics tools. All corresponding depictions are generated from MDL molfiles. The specification of biochemical pathways relies on the knowledge stored in PubChem and ChEBI.

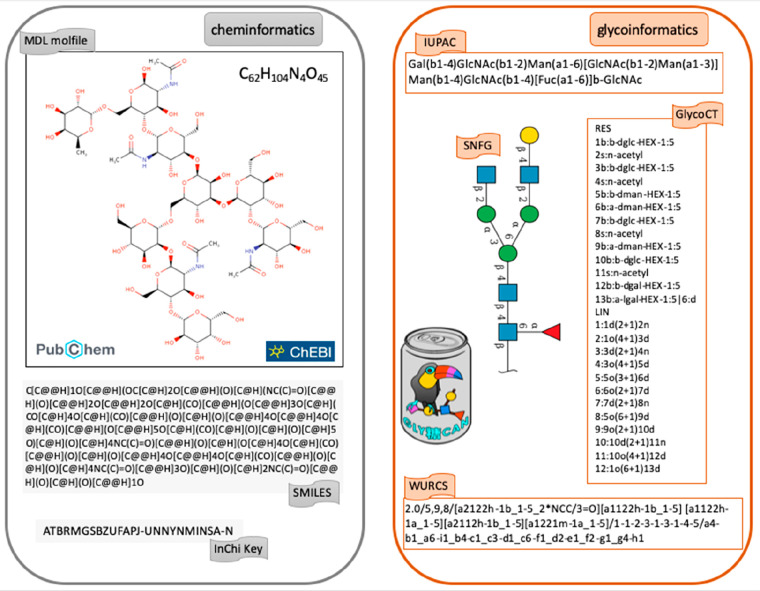

The convergence of cheminformatics with glycoinformatics is not as clear. All glycans of GlyTouCan are encoded in in IUPAC,36 GlycoCT,37 and WURCS.38 Each structure in this database is represented in the symbol nomenclature for glycans (SNFG) that has been adopted as a standard in glycoscience.39,40 Nonetheless, in recent years, closer interactions between GlyTouCan, PubChem, and ChEBI led to include the WURCS encoding and the SNFG notation in glycan entries of the latter two databases. Figure 2 illustrates the parallel options taken in cheminformatics and glycoinformatics. It should be noted that Figure 2 highlights the best case scenario of a fully defined structure. In reality, glyco-data often lack compositional or linkage information that is better handled by glycoinformatics-specific formats.157

Figure 2.

Contrast of encoding schemes for the same compound in cheminformatics and glycoinformatics. The left panel shows the depiction of C62H104N4O45 as provided in the PubChem and ChEBI databases of chemical compounds. These resources rely on the SMILES and InChi or InChi Key encodings that are used as popular input formats in many cheminformatics and bioinformatics tools. The right panel displays the most commonly used formats in glycoinformatics, namely IUPAC, GlycoCT, and WURCS. In the center, C62H104N4O45 is depicted in the symbol nomenclature for glycans (SNFG), now spreading both in glycoinformatics and in the literature.

The usage of multiple nomenclatures requires continuous harmonization. For example, when a new monosaccharide substituent (or modification, such as added phosphate or methyl) is discovered, it must be included in the encoding format (except for WURCS that was created partly to avoid this situation). This, in turn, impacts conversion software that must be maintained.158 These efforts are costly but essential in keeping a connected community. Another illustration of confusion created by multiple and independent contributions is the case of drawing glycan structures. The uncoordinated development of web interfaces have resulted in a panoply of different tools,41 which allow researchers to easily visualize glycan structures in their presentations and publications. This gave rise to a substantial variety of (i) specific colors for monosaccharides, (ii) depictions of linkage (undirected, directed, dashed) (iii) and linkage label (β1-4, β4, 4, 14β), and (iv) choice of reducing end depiction (nothing, protein backbone, OH). In the case of plant or fungal polysaccharides, there is also an abundance of trivial names (such as arabinan or glucan) as well as the ambiguity of where the repeating unit starts. Not only is such a variety detrimental to the implementation of a universal depiction such as SNFG, it also makes it confusing for newcomers to the field to understand meaningful associations in the visualization of glycan structures.

3. Glyco-data Representation

3.1. Lessons Learned from Bioinformatics

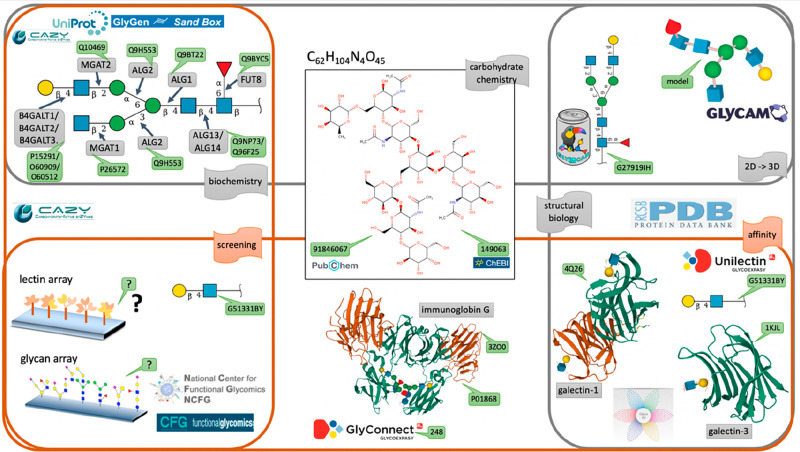

The precise recording and depiction of the heterogeneous information illustrated in Figure 1 is a definite glycoinformatics challenge. Figure 3 highlights the possibility of referring each and every entity: a glycan, its biosynthetic pathway, or the epitopes it contains, in an appropriate database, with a unique and stable identifier. This view is widely spread in bioinformatics and not completely realistic in glycoinformatics. To be effective, FAIR principles mentioned in the introduction apply to data and metadata (information about that data). For that reason, minimizing ambiguity is of the essence. The precision of description is guaranteed by associating each piece of data with a database identifier, shown as green tags in Figure 3 in a reproduction of Figure 1. Most of the cited databases also contain metadata.

Figure 3.

Diversity of bioinformatics resources with database identifiers. The exact same illustration of Figure 1 is kept and complemented with IDs (green tags) from the selection of relevant databases. Enzyme data can be found in both the CAZy and the UniProt databases. The GlyGen Sand Box provides the details of each step of biosynthesis. Structural details of glycoproteins and glycan-binding proteins are provided by the PDB channelled through the GlyConnect and UniLectin3D databases, respectively. Screening data are not precisely specified.

Biochemical knowledge has been traditionally covered by the CAZy database, where cazymes (carbohydrate-active enzymes) are collected and classified.42 CAZy revolves around amino acid sequence annotation and has grown in the past decades in close relation with NCBI genomes,43 Swiss-Prot,44 and UniProt,8 allowing the unambiguous characterization of cazymes via sequence accession numbers. In 2021, the GlyGen project45 released an interface to visualize the stepwise synthesis of GlyTouCan registered structures, called the SandBox [https://glygen.ccrc.uga.edu/sandbox/]. From a structural biology point of view, precision is brought by the knowledge of three-dimensional protein structures stored in the Protein Data Bank (PDB).46 A plugin to the LiteMol structure visualization software conveniently represents carbohydrates attached or bound in the 3D-SNFG representation;47 in this example, the known N-acetyllactosamine terminal motif of the example N-glycan structure, referred to as ID G27919IH in GlyTouCan. N-Acetyllactosamine is also recorded in GlyTouCan as ID G51331BY to provide a precise ligand definition, which can be used in turn by UniLectin3D48 that covers knowledge of lectins, also known as carbohydrate-binding proteins. UniLectin3D uses PDB IDs to reference lectins that are human galectins in this example. GlyTouCan ID G27919IH also appears in the GlyConnect database49 as attached to human immunoglobulin gamma (GlyConnect ID 278; UniProt P01868; PDB 3ZO0). Figure 3 also reveals the weakness of the screening information. Many array experiments are undertaken, but very few are collected. It was the purpose of the Consortium for Functional Glycomics50 at the turn of the century, but this initiative has ended. The National Center for Functional Glycomics has taken over and is preparing the launch of a new repository [https://ncfg.hms.harvard.edu/microarrays]. Other initiatives, such as GlyMDB51 or CarbArrayArt, have made provision for storing array data in a rational manner.159

Glycan data management and exchange is significantly helped by the Minimum Information Required About a Glycomics Experiment (MIRAGE) project initiated by the Beilstein Institute in 2011 [https://www.beilstein-institut.de/en/projects/mirage/].52 It follows the Minimum Information Standard movement that has produced sets of guidelines and formats for reporting experimental data in the past two decades, especially those generated with high-throughput methods [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minimum_information_standard]. At this point in time, very few glycoinformatics resources collect raw data to make them accessible to the community. As discussed for mass spectrometry data,53 channelling data through a pipeline is needed but to date still incomplete. GlycoPOST54 is the first implementation of a working MS data repository. Cited glycan array-related projects are compliant with the corresponding guidelines.55

Each of the data sources mentioned above attempt to comply with existing controlled vocabularies and ontologies as pointed out as mandatory in the FAIR principles.

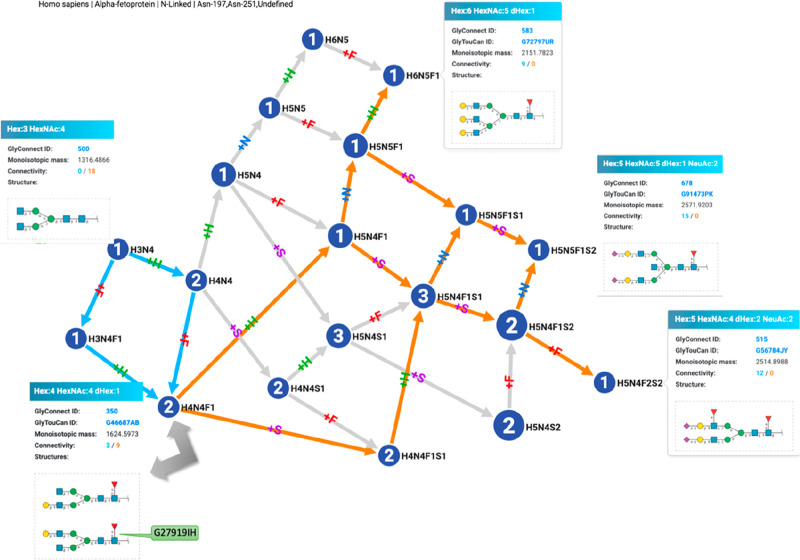

3.2. Lessons Learned from Proteomics

The dominance of mass spectrometry (MS) in proteomics sets a precedent for glycomics. In particular, the evolution of peptide MS data processing offers clues to handling glycan and glycopeptide MS data. In the early days of proteomics, the main objectives of MS data processing were the improvement of protein identification and the increase of its rate via automation,56,57 giving rise to lists of identified proteins in association with a tissue or a cell line. Rapidly, the need for making sense of those lists spurred the implementation of tools, enabling comparative methods.58 Finally, the concomitant development of interactomics led to map protein interaction networks to support the interpretation of coidentified proteins in a sample.59 As glycomics lags behind proteomics, the progression is similar but not as advanced. At this point in time, lists of identified glycans are being published yet often still lacking a precise identifier despite the existence of a universal glycan data repository.18 These lists are often provided as independent items and their possible relatedness limited to the determination of trends. Many publications report sialylation, fucosylation, or bisecting GlcNAc (among others) as prevalent features of a glycome content, which are in turn considered as a summary representation of a list. Nonetheless, the dependency of listed structures is reflected in glycan synthesis, which is a stepwise process easily visualized with graphs in which each connection represents the addition of a single monosaccharide. Figure 4 shows such a graph where GlyTouCanID G27919IH is now shown as a component of the human alpha-fetoprotein (UniProtID P02771). This representation was generated by GlyConnect Compozitor that processes glycan compositions,60 as opposed to defined structures, to handle current glycoproteomics data stored along glycomics data in the GlyConnect database. In Figure 4, the graph represents the glycome of human α-fetoprotein (UniProt ID: P02771) as recorded in GlyConnect and curated from seven publications. The view is centered on the composition corresponding to G27919IH and shows highlighted paths in cyan to map G27919IH substructures and in orange to map all structures, of which G27919IH is a substructure. Each leaf of the graph in that example is shown to emphasize the possible diversity in a single protein glycome.

Figure 4.

Relatedness of glycan structures of the human α-fetoprotein glycome (mapped with GlyConnect Compozitor). This representation emphasizes how listed glycans composing a protein glycome are tied together in terms of shared substructures. In this graph, cyan incoming paths connect glycan compositions and associated structures to GlyTouCanID G27919IH, as its substructures while orange outgoing paths connect G27919IH to glycan compositions and associated structures that include it.

4. Classical Machine Learning in Bioinformatics

4.1. Decades of Trials and Errors

It took almost two decades to realize the power of applying dynamic programming61 to amino acid sequence alignment62 but only two years for early bioinformaticians (not designated as such at the time) to implement revitalised neural networks63 in gene promoter64 or protein secondary structure4,65 prediction from sequence data. From then on, the most efficient sequence motif/pattern prediction methods have heavily relied on machine learning (ML) methods. This approach was soon popularized in bioinformatics through the dissemination of a reference manual66 (2nd edition in 2001).

ML methods in the form of neural net(work)s (NN), support vector machine (SVM), and some versions of hidden Markov models (HMM) have been applied to a broad variety of prediction, classification, and discovery related problems. The point of this review is not to cover these topics in detail and repeat previous work (see numerous references in Briefings in Bioinformatics, Oxford Press) but to provide a few landmarks in order to set the scene for introducing the application of ML in glycoscience. Note that ML in cheminformatics was previously and extensively described in this journal for text mining.67

In a nutshell, ML techniques require a set of examples (training set) from which regular features are extracted to define the profile of elements of the training set. A scoring function is then defined and used to decide whether a new object matches the learned profile. This very short summary emphasizes the importance of describing the examples with appropriate descriptors that will provide the salient features to be extracted. Furthermore, the examples need to be carefully selected to be considered as representative of the aimed-for trend and, unless maintained and/or providing the option of retraining, the application of an ML method is not valid for long.

Numerous ML-based applications have come and gone with the expansion of -omics and systems biology. On the one hand, the exponential growth of data sets has regularly challenged bioinformatics tools that could not scale or keep up with updates. On the other hand, examples in genomics suggest that it can be exceedingly difficult to avoid bias and overconfidence when applying ML to biological data.68 In contrast, the prediction of protein export cleavage sites illustrates the value of a well-defined problem that finds a suitable ML solution withstanding the test of time. SignalP69 was first released in 1997 and, in its current sixth version, is still widely used for predicting the presence of an N-terminal signal peptide. The full coverage of the development and evolution of the tool up to version five was recently reviewed.70 Suffice to say that SignalP 1.0 was implemented a neural network (NN), while SignalP 2.0 included a supplementary HMM prediction. This addition aimed at distinguishing signal peptides from anchors. SignalP 3.0 introduced a new D-score to strengthen the specificity of signal peptides compared to other sequences complementing the HMM prediction. SignalP 4.0 was shaped back as a pure NN-based method that turned out having blind spots that were corrected in SignalP 4.1. To keep up with learning method improvement, a shift to deep learning was initiated in 2018 with the release of SignalP 5.0,71 designed to account for signal diversity across species. In fact, SignalP 5.0 and its recent successor SignalP 6.072 belong to section 5 of this review, and they are cited here simply to highlight the value of a well-formulated problem relying on well-defined data. In this case, an ML-based prediction tool was adapted over 25 years, to evolving technology through thoughtful upgrades. SignalP 6.0 now considers five types of signal peptide at each position and relies on a BERT-type language model (see section 5).

4.2. Useful Toolboxes

ML methods have been democratised with the release of libraries such as WEKA,73 Shogun [https://www.shogun-toolbox.org/], and mlpack,74 to name a few, that allow for fast implementation and integration into computational analyses . Next to providing predictions from biological data, ML methods also allow researchers to work with learned similarities (also called representations or embeddings), to visually and quantitatively compare samples. Ranging from protein sequences to tandem mass spectrometry spectra, complex data is usually very high-dimensional and therefore hard to visualize and understand in a granular manner. A benefit of applying machine learning to these types of data is that a numerical representation is learned, which can be projected into two-dimensional space (amenable to plotting it) by a variety of methods. Examples of this are distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) or uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP75), both of which aim at finding a two-dimensional formulation of the data that best preserves distances in the original dimensionality.160 These methods are particularly popular in the single cell-based -omic fields with a tendency to create opposing communities.76,77

4.3. First-Generation AI for Glycomics (1990–2004)

4.3.1. Optimizing Mass Spectrometry Processing

Some parts of the mass spectrometry (MS) pipeline provide opportunities for automation and enhancement via machine learning. Although initially designed for proteomics, the fine-tuning of data analysis offers valid points for glycomics. Probabilistic models were first introduced to train the prediction of peptide fragment intensities in MS/MS.78 Then, the generalized use of a false discovery rate (FDR) as a confidence assessment of peptide identification has led to the design of efficient scoring schemes supporting the discrimination between experimental and decoy mass spectra, as implemented in Percolator79 or in Barista80 software tools. Note that FDR calculations are still lacking in most glycoproteomics data analysis software, as revealed in a recent community challenge.81

De novo sequencing is another challenging area of MS-based identification both in proteomics and glycomics, although not yet conclusive in the latter case. A support vector machine (SVM) model was for instance proposed to optimize the score of cross-ring ions and other structural features in order to improve structure assignment from MS/MS spectra.82

4.3.2. Predicting Glycosylation Sites

Searching for glycosylation patterns has very early on provided challenging questions for ML methods. In N-glycosylation, glycans are bound to a nitrogen atom of an asparagine (Asn or N) residue. The attachment on this amino acid was shown to be characterized by a short consensus sequence: N-X-S/T where S is a serine (Ser), T is a threonine (Thr), and X is any amino acid except proline83 (Pro or P). In O-glycosylation, glycans are linked to an oxygen atom of a serine (S) or a threonine (T) and, occasionally, to a hydroxyproline or a tyrosine. No consensus sequence has been observed around O-glycosylated sites except for an unusual abundance of hydroxylated amino acids. Sequence alignments emphasized the frequent occurrence of proline residues close to the glycosylation sites, especially just before and three positions after the glycosylated residue. In contrast, the presence of charged amino acids at these sites tends to prevent the placement of glycans.84 In C-glycosylation, also called C-mannosylation, glycans get attached to the carbon atom of a tryptophan (Trp or W) residue and the W-X-X-W motif was identified as the acceptor consensus sequence for glycan binding.

Notable efforts in bioinformatics have boosted both the discovery and mapping of O- and N-glycosylation sites. Results of large-scale mapping of human N-sites has been collected in UniPep85 (found on proteins isolated from plasma, cerebrospinal fluid, various tissues, and cell sources) and N-glycosite Atlas86 (22 human tissues/body fluids). A genetic engineering approach using human cell lines has enabled proteome-wide discovery of GalNAc-type O-glycosylation sites.87 Despite the value of these data sets and the development of new technologies, the experimental determination of glycosylation sites only roughly characterizes glycans. To compensate for the lack of data, in silico prediction has been, and continues to be, developed mainly based on ML methods. These were trained primarily to recognize the protein sequence context but also secondary structure features and accessibility of glycosylated residues.

Neural networks were implemented early on in a set of online tools made available from the late 1990s on a server of the Technical University of Denmark. The collection spanned the prediction of N-glycosites with NetNGlyc, O-glycosites with NetOGlyc, as well as in O-GlcNAc sites with YinOYang.88 The training sets used in each case were very limited at the time and, expectedly, did not yield highly reliable results. Nonetheless, they settled as references in the field. Years later, the sensitivity of NetOGlyc considerably improved following the massive information input provided by Clausen and colleagues.87

4.4. Second Generation (2005–2015)

4.4.1. Random Forest and Support Vector Machines

Two approaches destined to increase learning quality of neural networks were introduced a few years later, namely support vector machines (SVMs)89 and random forest (RF),90 and both were used to refine the quality of glycosite prediction. All of the corresponding contributions demonstrated how they outperformed NetNGlyc and NetOGlyc following this enhancement. On the basis of a random forest implementation, GlycoMine91 was shown to improve the prediction performance for the three major types of glycosylation in human. The method relies on employing intensive feature selection techniques and integrating several informative features (e.g., sequence-based, structural, and functional features) to predict the glycosylation sites in a protein of interest. However, the online version of GlycoMine was last updated in August 2017 and is currently accessible only via an archived web-link [https://web.archive.org/web/20170812131319/http://www.structbioinfor.org/Lab/GlycoMine/]. The GPP (glycosylation prediction program)92 also relies on a random forest predictor exclusively based on protein sequence features. Other software solutions hinge on the implementation of SVMs, whether single in GlycoEP93 on multiple protein features (sequence, structure, etc.) or combined in EnsembleGly94 on strictly sequence features or part of a multistage approach as in N-GlyDE,95 also relying on multiple structural protein features and calculated features such as gapped dipeptides. Table 1 recapitulates this range of published tools and helps comparison. In general, pre-existing methods to calculate protein features such as secondary structure,96 are selected and integrated in the prediction workflow.

Table 1. Summary Table of Cited Methods for Glycoprotein Site Prediction.

| tool name | N/O glycans | method | features |

|---|---|---|---|

| NetNGlyc | N | NN | sequence |

| NetOGlyc | O | NN | sequence, structure |

| GlycoMine | N/O | RF | sequence, structure, functional |

| GPP | N/O | RF | sequence |

| GlycoEP | N/O | SVM | sequence, structure, evolutionary |

| EnsembleGly | N/O | SVM | sequence |

| N-GlyDE | N | SVM | sequence (gapped dipeptides), structure |

| SPRINT-Gly | N/O | SVM/NN | sequence, structure, physicochemical, evolutionary |

| DeepNGlyPred | N | NN | sequence (gapped dipeptides), structure, evolutionary |

The prediction of O-GlcNAcylated sites in DB-OGap97 was also considered an improvement over YinOYang with an amino acid sequence-based SVM model and more recently with a combination of techniques spanning SVM and random forest.98

In the end, none of these methods include training data accounting for the actual structures attached on N- or O-sites despite the earlier suggestion that distinct structural features of glycans correlate with protein structure99 and the observed changes in protein sequence alignment surrounding sites depending on the properties of attached structures, e.g., core-fucosylated vs nonfucosylated.100

Naturally, improvement was also sought in N-glycopeptide identification from tandem MS data. SVMs101 as well as random forest102 were introduced to define more effective scoring schemes for intact glycopeptide-spectrum matches. Yet the limited reliability of intact glycopeptide identification from MS data, as recently demonstrated,81 is not related to the use or absence of use of ML-based scoring functions.

4.4.2. Classifying Glycans

Probabilistic models and machine learning methods are commonly brought together as complementary approaches in bioinformatics and this observation transfers to glycoinformatics. In particular, the tree-shaped structures of glycans have inspired bioinformaticians to use hidden Markov models (HMMs) to classify glycan structures.103 Other attempts produced SVM-based glycan classification,104 but these paths have not been further explored.

5. Next-Generation Machine Learning

5.1. Background

Deep learning has recently revolutionized the analysis of large volumes of biological sequences. One key advantage of deep learning is the ability to work with “unstructured” data, such as sequences or images, without having to define or calculate features that are used for establishing correlations or for training a model.105 Instead, the deep learning model (ideally) learns the relevant features in a data-driven manner that are then used for prediction. This makes large data sets, such as sequence repositories, directly accessible for being used for model training and has the potential to be less biased and more potent, as features are not restricted to human-defined data characteristics. A key distinction in deep learning models is their separation into “supervised” and “unsupervised” models. Supervised models are trained with known labels, which means that, given the features (e.g., sequence etc.) of a data point, the model aims to predict the label (e.g., protein function). Unsupervised models, on the other hand, only have access to features, not labels. In this case, the model merely learns similarities of data points based on their features. An example would be an unsupervised model trained on protein sequences that would allow clustering of these proteins based on their learned similarity.

A multitude of different model architectures, algorithms of how to learn mapping the input to the output, are available and used in deep learning applied to biology. The ones relevant in the context of glycobiology are feed-forward neural networks, recurrent neural networks, graph neural networks, and transformer-based models. In feed-forward neural networks, a number of layers is constructed, in which each layer learns a function for combining the output from the previous layer to achieve a meaningful prediction of the output at the final layer.106 This architecture was one of the first historical deep learning methods and remains relatively simple yet popular in usage. Language models, such as recurrent neural networks (RNNs) or transformer-based methods, were originally developed to analyze human languages such as English, yet have been applied to the analysis of biological “languages”, such as DNA or proteins, as well. Another prominent architecture that recently also surfaced in computational biology is the transformer. In RNNs, inputs are analyzed sequentially, e.g., using each word of a sentence as an input to the model and propagating the intermediate output of this procedure to the analysis of the next word.107 As a consequence, RNNs exhibit a limited form of memory, important in analyzing sequential data. The key principle of transformer-based methods is to abandon the sequential approach and analyze language-based data simultaneously.108 This is made possible by the application of “attention”, an algorithmic trick to let the model learn which parts of the sentence/sequence are relevant in the context of prediction. Finally, graph neural networks have been developed to analyze nonlinear data formats, from social media networks to protein 3D structures.109 The key operations here are convolutions and pooling to convert the irregularly shaped graph input into a fixed-size set of numbers that can be used to reach a prediction. Convolution operations describe nodes in a graph by the features of its neighbors, while pooling operations condense the information from this process, for instance, by collecting maximal or mean values from the convolutions across the graph.

The most prominent application of deep learning in biology in recent history can be seen with the emergence of protein structure prediction models such as AlphaFold2.7 Providing a scalable means of predicting 3D structures of proteins from their sequence, AlphaFold2 also already impacted glycobiology, with the potential of integrating modeled carbohydrate structures with AlphaFold2-derived protein structures.110 Another example of how deep learning, applied to biological sequences, has advanced glycobiology can be found in the prediction of glycosites using neural networks and protein sequences,87 as discussed above. From a chemistry perspective, Ardejani et al. recently presented the combination of quantum mechanical calculations and machine learning to study protein–N-glycan interactions in detail.111 These applications and others predominantly build on the prolific literature on protein-focused deep learning and large associated data sets.

5.2. Deep Learning and Glycobiology

Despite the proliferation of the literature on this topic, the deep learning-driven analysis of proteins has only begun relatively recently, with the development of algorithms such as UniRep112 in 2019, that was designed to learn the fitness of point mutation variants. In the case of UniRep and most other deep learning-based language models, protein sequences are viewed as a biological language, with amino acids as characters of a (very long) protein “word”. The model is then trained by predicting the next character (i.e., amino acid), given the preceding characters. For this prediction task, models such as UniRep not only consider the identity of amino acids but also can learn amino acid properties (akin to size, polarity, etc.) via a trainable embedding or, synonymously, representation. This representation vector, once properly trained, can be viewed as expressing amino acid similarity, as the distance of the representation of two physicochemically similar amino acids such as aspartate and glutamate, should be smaller than two very dissimilar amino acids such as glycine and arginine. Once trained on this character-by-character approach, the final model can then consider the full protein sequence to predict protein properties.

Machine and deep learning approaches for protein sequences can have immediate implications for glycobiology, such as when they are applied to glycosyltransferases. Using calculated protein sequence properties as input for a gradient-boosted regression tree model, monosaccharide donor specificity could be predicted for fold A glycosyltransferases.113 Shortly after, the same authors presented a deep learning approach, using a convolutional neural network with attention, to predict the fold of glycosyltransferases from their sequence.114 This allowed them to identify glycosyltransferase families which are likely to exhibit novel folds that should be further investigated with regard to their structure.

Corresponding analyses for applying deep learning directly to glycans have emerged later than those for proteins, such as SweetTalk.115 Many reasons for this delay could be mentioned: (i) a relative lack of available sequence data that could support large unsupervised model training, (ii) a relative lack of available labeled data that connects glycans with properties or outcomes for supervised model training, and (iii) the sequence diversity of glycans, comprising hundreds of building blocks and nonlinear sequences due to branching.

The first advances of deep learning applied to glycan sequences have largely mirrored developments in applying AI to proteins. This included the development of models treating glycans as a list of features (see GlyNet116), a biological language (see SweetTalk115 and glyBERT117), or as molecular graphs (see SweetNet118). A general observation here is that, over time, models have changed to accommodate the branched, nonlinear nature of glycans, which has led to substantial improvement in the quality of predictions.118

Models treating glycans as a list of features stem from a long history in drug development, for which “fingerprinting” is a common practice.119 Here, a chemical is described by a list of standardized features, for instance the absence/presence of certain chemical moieties or the connectivities of atoms. Analogously, glycans can be characterized by a vector cataloguing the absence/presence/number of sequence motifs, for instance on the monosaccharide or disaccharide level. Importantly, fingerprints of this type are not bijective, as it is not generally possible to uniquely reconstruct a glycan from its fingerprint, and one fingerprint may describe several distinct glycans exhibiting these motifs in different configurations. The fingerprint is then used as input for, typically, a feed-forward neural network, a model with multiple layers that learns a function to combine information from previous layers into subsequent layers. Here, each neuron of the first layer has access to information on one feature of the fingerprint, which then is further combined in later layers of the model before arriving at a prediction that is informed by information from the fingerprint.

Glycan language models are closest to the protein language models mentioned above. However, differences arise between the different language models. One distinctive aspect is what a token signifies in a model. One such model type would be the transformer, a model designed for handling sequential data. A transformer does not process a sequence from beginning to end but rather learns from parts of the sequence. In other words, a transformer identifies the meaningful bits. In the transformer-based glyBERT, a token corresponds to a monosaccharide, while the recurrent neural network-based SweetTalk considers larger units, trisaccharides, as tokens in the language of glycans. A recurrent neural network is also designed for sequential data but does process a sequence from beginning to end, keeping previous parts of the sequence in memory to arrive at a final prediction. Next, the process of model training also differs between the two model types. SweetTalk-type models function analogous to UniRep described before by predicting the next token given the previous tokens. Transformer-based models such as glyBERT, however, operate by the principle of attention:120 given the whole sequence, the model learns which parts are salient (i.e., important for prediction) in order to focus on them with regard to prediction. Both types of models also have an embedding layer, as described in the context of UniRep, to learn similarities of monosaccharides or larger structures.

Finally, graph neural networks consider glycans to be akin to molecular graphs, with precedent models in drug discovery that treated chemicals as molecular graphs.121 This is fitting in the context of glycans, as glycans are trees, branched sequences with no full cycles, and therefore a special case of graphs. From this viewpoint, a monosaccharide can be considered a node in this graph and, similar to the other discussed techniques, each node type can have its own features, namely a trainable embedding vector. Graph convolutional neural networks, such as the mentioned SweetNet, learn graph “neighbourhoods” via several convolution operations. A convolution in this context is a filter that is iteratively applied over the whole graph to only continue with relevant information in the rest of the model. Each convolution considers the features (i.e., embeddings) of neighboring nodes to describe a node. Each subsequent convolution then has a wider definition of what constitutes “neighbouring”, describing a larger portion of the graph in the process. After doing this for every node and its neighborhood, these description features are then passed along to a neural network that uses this learned graph representation to arrive at a prediction.

As already mentioned, deep learning models for glycans have the additional advantage of learning glycan similarity, a concept which can of course also be expressed without machine learning in principle, for instance via counting motifs.122 In various contexts, learned glycan similarities have been shown to cluster by glycan class and/or characteristic motifs.118 Next to being used for downstream models that can use these similarities as new features for prediction, learned glycan similarities can be used to visualize clusters of related glycans, for instance via t-SNE or UMAP mentioned above, and allow for interpretation of learned glycan associations. In a recent study, this has been for instance used for an in-depth investigation of the role and properties of different fucose-containing motifs across taxonomic kingdoms.123

5.3. Glycosite Prediction

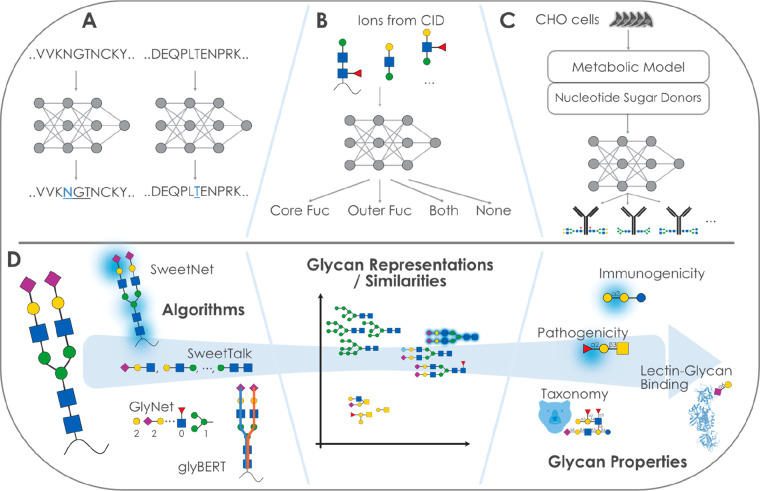

As mentioned in section 4.4.1, glycosite prediction remains a challenge without the inclusion of glycan data. Nonetheless, the two most recent additions to the available models for the prediction of N-glycosylation have implemented deep learning methods (see Figure 5A). SPRINT-Gly124 trained an SVM and deep NNs on calculated amino acid, evolutionary, structural, and physicochemical features, and, in the same vein, DeepNGlyPred125 is a deep NN, trained on sequence-based features (e.g., gapped dipeptides), predicted structural features, and evolutionary information. Table 1 recapitulates the glycosite predictive tools cited in sections 4.3.2 and 4.4, as well as in the present one.

Figure 5.

Applying next-generation machine learning to glycobiology. (A) Neural network-based models can be used to predict glycosylation sites from protein sequences. (B) The fucosylation state of glycopeptides can be predicted via neural networks or support vector machines from ion fragments. (C) On the basis of a metabolic model and a neural network, the distribution of glycosylation states of recombinant proteins could be predicted in CHO cells. (D) Using deep learning to predict glycan properties. Several algorithms with their conceptual approach to analyzing glycan sequences are shown. These algorithms learn a glycan similarity or representation that can be used for clustering. The same learned features can also be used to predict a variety of glycan properties, some of which are shown here.

5.4. From Mass Spectrometry to Glycosylation

To solve, or at least ameliorate, the relative lack of data in glycobiology, improvements in the data acquisition pipeline are necessary for advancing glycan-focused deep learning. Recent work has focused on evaluating the potential of machine learning and deep learning to achieve these improvements. For example, both support vector machines (SVM; machine learning) and neural networks (NN; deep learning) were assessed to predict core and outer fucosylation from glycopeptides, specifically from CID-based ions126 (see Figure 3B). Encouragingly, both the SVM and the NN model matched manual interpretation, resulting in a near-perfect prediction when assuming that the manual interpretation reflects the biological reality. Approaches such as this could lead to a considerable improvement in speed, cost-efficiency, and, thereby, throughput. Other recent endeavors rely on deep learning, such as on the usage of bidirectional recurrent neural networks, to predict fragment ion intensities.127 Deep learning was also used in Prosit,161 with which both fragment ion intensity and retention time are predicted. Prosit combines a bidirectional recurrent neural network, applied to protein sequences, with an attention layer. Similar methods for the prediction of glycan fragmentation would be advantageous for advancing glycomics.

In data-independent acquisition, the prediction of peptide fragmentation in tandem mass spectrometry is a major focus for deep learning approaches, with great progress for predicting peptide fragmentation,128 while glycopeptide fragmentation prediction still may require further advances until spectral libraries are no longer necessary.129

Generating glycosylation information without mass spectrometry would represent a paradigm shift in glycobiology. Thus, approaches that build on the knowledge base constructed so far and aim at this goal are not only a worthwhile focus but also dependent on advanced algorithms such as from deep learning. A recent neural network based on a metabolic model predicting nucleotide sugar donor concentrations as inputs, demonstrated that the proportions of a limited set of N-linked glycans could be predicted on four recombinant glycoproteins from three CHO cell lines130 (see Figure 5C). Extension and generalization of such a model could hold promise to advance glycoengineering efforts in the production of biopharmaceuticals.131

5.5. Using Deep Learning to Predict Glycan Properties

While the above section discussed advances in obtaining glycan sequences, we now turn to the question of what to eventually do with obtained glycan data to gain further insight into biological contexts. Analogous to deep learning models predicting protein properties from sequences, such as GO terms or EC numbers,132 recent developments in glycobiology have introduced a new generation of deep learning-based sequence-to-function models (see Figure 5D).

Current examples of predicting glycan properties from sequences include prediction of glycan class, taxonomy, immunogenic potential, and association with bacterial pathogenicity.115,118 Trained models in these tasks not only can be used to infer the properties of newly discovered glycans but also can be used to retrieve motifs that are important to endow a glycan with a property, such as human-like glycan motifs used in molecular mimicry by pathogenic Escherichia coli strains. Other notable efforts in this area, using machine learning, are the investigation of the association of clinical characteristics with glycans from cancer patients133 or the prediction of α-fetoprotein (AFP)-negative hepatocellular carcinoma using glycan fingerprints,134 both of which could offer a promising target for deep learning in the future. The key limiting factor in all applications of this type of supervised learning in glycobiology is the lack of labeled data of glycan sequences with known information about their properties or functions that could be used to train a model. Often this information may exist in sufficient quantity across the literature yet is scattered and would require exhaustive manual curation that may be prohibitively expensive.

One domain which has made considerable progress in solving this bottleneck via organized databases and resources, as mentioned above, is the study of lectin–glycan interactions. Here, resources such as the CFG array database or the UniLectin3D database for lectin–glycan crystal structures offer data that are more suitable for machine learning and related endeavors. Therefore, several machine and deep learning approaches have recently joined the statistical motif-counting methods to analyze glycan-binding data. An example is a recent study135 that used the structural data of UniLectin3D to train random forest-based models on computed physicochemical and geometric features of proteins to predict their binding to observed glycan fragments.

Other approaches have used glycan-binding data from glycan arrays, where lectins are probed for their binding to immobilized glycans on a glass slide.136 One example for this would be GlyNet,162 a neural network-based approach for using the motifs that occur in a glycan to predict its binding to the lectins that have historically been assayed on the CFG platform. Combining interpretable, rule-based machine learning with expert annotation has also recently resulted in the detailed elucidation of the binding motifs of a large set of commonly used lectins.137 In other work, glyBERT has been introduced as a transformer-based model for glycans that can also be used to learn the binding specificity of a lectin, provided that binding data exist. All the approaches above require dedicated binding data of the lectin that is being studied. Another recent approach to solve this limitation and the problem of predicting the binding specificity of a lectin has been put forward with LectinOracle,138 a deep learning model that combines a language model for the lectin sequence (the ESM-1b transformer model139) and a graph neural network for the glycan sequence (SweetNet) to predict lectin-glycan binding. By also considering the information of proteins, LectinOracle can generalize to new proteins as well as new glycans. For the relatively data-sparse field of glycobiology, such a strategy is crucial to at least provide predictions that can in turn generate new hypotheses for contexts with many uncharacterized lectins, such as the microbiome.

6. Gradual Impact on Glycoscience and Development Prospects

At this stage of method development in glycoscience, glycoinformatics provides a real chance for unifying a view of the molecular interactions mediated by glycans. From measurement (e.g., mass spectrometry fragmentation prediction) to biological context (e.g., glycosite prediction) and glycan properties as well as functions, glycoinformatics is advancing every facet of glycoscience and has the potential to continue doing so in the future.

6.1. Expected Evolution of AI in Glycoinformatics

6.1.1. Evolution of Data

At this point in time, a simple explanation for glycomics lagging behind other -omics lies in the absence of high-throughput sequencing of glycans. Consequently, data accumulates substantially slower than in genomics or transcriptomics. This is especially true for glycan classes outside of N- and O-linked glycans. The contrast is even more striking as bioinformatics is now geared to process petabytes of nucleotide sequences and run smart searches to reveal hidden information. Such massive sequence data crunching has already led to the identification of ∼105 unknown viral species.140 In that sense, the future of glycomics hinges on new technological development that may enable glycan high-throughput sequencing and also improve the analysis of other types of glycans such as glycosaminoglycans. Efforts in other fields, such as the recent advances toward protein sequencing, demonstrate that sequencing in principle can also be applied to non-nucleic acid biopolymers.141

Another key point regarding data collection is the current limited availability of quantitative data that would allow more accurate profiling. At present, immunoglobulin profiling is by far the most advanced in comparison to other glycoconjugates.142,163 Other prospects can be expected to expand from improved techniques in glycan and tissue imaging.143,144

6.1.2. Improved Prediction

Like in many scientific fields, AI methods are increasingly implemented to improve classification and prediction. Machine learning applied in various aspects of glycoscience (e.g., glycosite prediction or monosaccharide donor prediction for glycosyltransferases) still predominantly rely on human-devised, calculated features as model input. This is presumably the reason why classical machine learning methods (SVM, RF, etc.) currently often still outperform deep learning approaches on these tasks. One of the most important advantages of deep learning is that it allows for access to information beyond the rationally chosen features of a sample. It is therefore to be expected that deep learning approaches using raw sequences in a proper format will yield improved performance in the future. Another promising direction is the combination of calculated features and raw inputs, such as sequences, that has been shown to improve performance for small molecule property prediction.145

Additionally, while existing models are largely inclusive of less well-studied glycan classes, such as plant and fungal polysaccharides, in terms of their model architecture, there might be approaches that could perform better on tasks involving these polymers, for instance by considering their repeat structure. However, existing data for most prediction tasks described in this manuscript are largely restricted to N- and O- linked glycans as well as glycolipids and, in a limited manner, glycosaminoglycans. Therefore, both available data and existing models will likely need to be improved to fully leverage the information in polymeric glycans.

On the other end, the purpose of predicting glycan-binding is to design specific ligands, for instance to inhibit glycan-binding proteins of pathogens, but more context-sensitive information will be required to qualify specificity. In particular, realistic binding prediction is likely to depend on additional characteristics, such as expression of the lectin and physiological conditions. Ultimately, models will need to account for all of these aspects, as well as the structural features of glycoconjugates and glycan-binding proteins. These will be helped if 3D models are more systemically built while taking glycans into consideration, as made possible with AlphaFold2 predictions.110

6.1.3. Improved Representation

The learned numerical representation by ML models can also be used to find the most similar known data point, given a new unknown data point. In the context of tandem mass spectrometry in proteomics, this has been used to quickly assign unidentified spectra to peptides.146 A similar procedure in glycomics or glycoproteomics could advance these fields as well. Next to similarity, the learned representation gained by an unsupervised model can also be viewed as learned features of, say, a protein sequence, which can be used by another downstream model. An example for this can be found in the case of evolutionary scale modeling 1b (ESM-1b), a transformer-based language model trained on protein sequences.139 The learned representations from ESM-1b are multipurpose and can be used to predict various properties such as protein structure, stability, or function, with downstream models that do not need as many parameters as one would need if the model would be trained on protein sequences from scratch. While these learned protein features can be very useful in the glycosciences (e.g., glycosite prediction, glycan-binding prediction, etc.), eventually an analogous model for glycans might be needed to improve prediction tasks. This is especially relevant as the number of available labels for glycans, that could be used for training a model, is typically much lower than is the case for proteins, necessitating the usage of such a pretrained model for satisfactory performance.

Current models all focus on glycan sequences, processed in various ways. However, future models might have to include chemical as well as 3D information to achieve optimal results.164 In the case of proteins, joint representations of sequence and structure have shown improved performance for downstream models.147 There are already numerous indications that glycan conformation influences function and including this information into predictive models is bound to place them closer to the biological reality. Key challenges here are (i) how best to incorporate this information into existing or future glycan-focused artificial intelligence models given the conformational flexibility of glycans and (ii) how to obtain a sufficient number of glycan conformations. As reviewed earlier, the answers lie in the constant improvement of experimental techniques (for example, intact glycoprotein resolution can benefit from cryoelectron microscopy) as well as that of molecular dynamics (MD) simulation algorithms.148 The latter critically depend on the further increase of computer power and on the refinement of molecular aspects such as glycan placement on proteins.

6.2. Bridging Glycoinformatics and Bioinformatics

The importance of applying FAIR principles, promoted in bioinformatics and emphasized in the introduction as well as in section 3, has beneficial effects on glycoinformatics development that increasingly bridges with resources of other -omics and provides the means to expand systematism.

Single cell technologies have spread like wildfire in most -omics applications, providing each discipline with more specific and refined information on molecular activity and interactions. Glycomics has not yet benefited from such a step forward. It remains open to debate whether information is easier to obtain from genes and biosynthetic pathways that regulate glycosylation than from the direct analysis of glycan structures. At present, glycoengineering tends to be more advanced when handling genes,149 but this does not rule out a yet-to-come strictly single cell glycomics approach. First steps in this direction have added partial/fragmentary glycan information to the analysis of single cells and/or a combination with their transcriptome.150,151 Data integration will be facilitated by collecting same level information from different and complementing -omics. Nonetheless, attempts at combining views on regulation have already emerged, for example, by considering the interplay between microRNA and glycan expression152 or between gene transcription and glycan expression,153 and these are likely to expand in the very near future. In all cases, both bioinformatics and glycoinformatics resources are needed in this context. This bridging process is the core of an international cooperative approach named GlySpace,23 designed to facilitate structural and functional glycomic data sharing and information exchange and committing to provide high quality, reliable, well-referenced, and accurate data to the benefit of users. In parallel, the release of software libraries tailored for glycoinformatics applications consolidates this initiative. Several examples spanning the management of mass spectrometry data in Python154 or Java155 or handling ML tools156 are readily available for software developers.

6.3. Multiscale View

As mentioned in the introduction, the variety and disparity of sources of information that are needed to understand the details of glycan structure and function are still a hindrance to rapid progress in glycobiology. Ultimately, the goal of glycoinformatics is to restore a more thorough picture from pieces created artificially by technological constraints. For as long as this puzzle is, if not complete, at least advanced enough to allow for reliable predictions, it will concentrate efforts within glycoscience. However, the key contribution of glycans to biological processes, especially in cell–cell communication, cannot be ignored and, as mentioned above, glycomics should be combined with other omics. In fact, the ideal view of understanding living organisms is dynamic and starts from the atomic to the cellular, tissue, and organ levels. Multiscale modeling as the holy grail of systems biology must be fed with a refined knowledge of glycoscience.

Acknowledgments

D.B. acknowledges funding from the Branco Weiss Fellowship – Society in Science, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, and the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. F.L. acknowledges funding from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) grant 443 #31003A/179249, Glyco@Alps (ANR-15-IDEX-02) and the Swiss Federal Government through the State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation (SERI).

Glossary

Abbreviations/Acronyms

- AI

artificial intelligence

- BERT

bidirectional encoder representations from transformers

- CASP

critical assessment of protein structure prediction

- CAZy

carbohydrate-active enzymes

- CID

collision-induced dissociation

- CFG

Consortium for Functional Glycomics

- ChEBI

chemical entities of biological interest

- DL

deep learning

- EC

enzyme commission number

- ESM-1b

evolutionary scale modeling 1b

- FAIR

findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable

- FDR

false discovery rate

- Fuc

fucose

- Gal

galactose

- GalNAc

N-acetylgalactosamine

- Glc

glucose

- GlcNAc

N-acetylglucosamine

- GO

gene ontology

- HMM

hidden Markov model

- HTTP

hypertext transfer protocol

- InChI

IUPAC international chemical identifier

- IUPAC

International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry

- MIRAGE

minimum information required about a glycomics experiment

- Man

mannose

- MD

molecular dynamics

- ML

machine learning

- MS

mass spectrometry

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- NN

neural network

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

- RF

random forest

- SMILES

simplified molecular input line entry system

- SNFG

symbol nomenclature for glycans

- SVM

support vector machine

- t-SNE

t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding

- UMAP

uniform manifold approximation and projection

- WURCS

Web3 unique representation of carbohydrate structures

Biographies

Daniel Bojar is a tenure-track assistant professor in bioinformatics at the Department of Chemistry and Molecular Biology and the Wallenberg Centre for Molecular and Translational Medicine at the University in Gothenburg. After a Ph.D. in mammalian synthetic biology at ETH Zurich and a postdoctoral stay at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University, his group now focuses on research at the intersection of glycobiology and machine learning. Dr. Bojar has received a Branco Weiss Fellowship—Society in Science, a Foresight Fellowship, and is on the 2022 Forbes 30 Under 30 Europe list.

Frederique Lisacek received a Ph.D. in Computer Science (Artificial Intelligence) from the University Pierre & Marie Curie, Paris, France. Then, she has held research positions in bioinformatics in France, Japan, and Australia, working on knowledge representation and sequence analysis in various fields of molecular biology. She has been involved in early proteomics projects within two companies Proteome Systems Ltd in Sydney, Australia, and Geneva Bioinformatics (GeneBio) SA. In 2006, she joined the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (SIB) in the Proteome Informatics Group that she has managed since 2008 and where she initiated several projects on the study of protein posttranslational modifications, with a strong focus on glycosylation. She holds a lecturer position at the University of Geneva.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Aoki-Kinoshita K. F.; Lisacek F.; Karlsson N.; Kolarich D.; Packer N. H. GlycoBioinformatics. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2021, 17, 2726–2728. 10.3762/bjoc.17.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson M. D.; Dumontier M.; Aalbersberg Ij. J.; Appleton G.; Axton M.; Baak A.; Blomberg N.; Boiten J.-W.; da Silva Santos L. B.; Bourne P. E.; et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160018. 10.1038/sdata.2016.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbon S.; Douglass E.; Good B. M.; Unni D. R.; Harris N. L.; Mungall C. J.; Basu S.; Chisholm R. L.; Dodson R. J.; Hartline E.; et al. The Gene Ontology Resource: Enriching a GOld Mine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D325–D334. 10.1093/nar/gkaa1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian N.; Sejnowski T. J. Predicting the Secondary Structure of Globular Proteins Using Neural Network Models. J. Mol. Biol. 1988, 202 (4), 865–884. 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90564-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fariselli P.; Olmea O.; Valencia A.; Casadio R. Prediction of Contact Maps with Neural Networks and Correlated Mutations. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2001, 14 (11), 835–843. 10.1093/protein/14.11.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.; Sun S.; Li Z.; Zhang R.; Xu J. Accurate De Novo Prediction of Protein Contact Map by Ultra-Deep Learning Model. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13 (1), e1005324 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumper J.; Evans R.; Pritzel A.; Green T.; Figurnov M.; Ronneberger O.; Tunyasuvunakool K.; Bates R.; Žídek A.; Potapenko A.; et al. Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596 (7873), 583–589. 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A.; Martin M.-J.; Orchard S.; Magrane M.; Agivetova R.; Ahmad S.; Alpi E.; Bowler-Barnett E. H.; Britto R.; Bursteinas B.; et al. UniProt: The Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D480–D489. 10.1093/nar/gkaa1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirdita M.; Schütze K.; Moriwaki Y.; Heo L.; Ovchinnikov S.; Steinegger M. ColabFold - Making Protein Folding Accessible to All; preprint. Nature Methods 2021, 19, 679. 10.1038/s41592-022-01488-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doubet S.; Bock K.; Smith D.; Darvill A.; Albersheim P. The Complex Carbohydrate Structure Database. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1989, 14 (12), 475–477. 10.1016/0968-0004(89)90175-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez S.; Mulloy B. Prospects for Glycoinformatics. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2005, 15 (5), 517–524. 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lütteke T. The Use of Glycoinformatics in Glycochemistry. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2012, 8, 915–929. 10.3762/bjoc.8.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F.; Glinskii O. V.; Glinsky V. V. Glycobioinformatics: Current Strategies and Tools for Data Mining in MS-Based Glycoproteomics. PROTEOMICS 2013, 13 (2), 341–354. 10.1002/pmic.201200149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egorova K. S.; Toukach P. V. Glycoinformatics: Bridging Isolated Islands in the Sea of Data. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57 (46), 14986–14990. 10.1002/anie.201803576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M. P.; Aoki-Kinoshita K. F.; Lisacek F.; York W. S.; Packer N. H.. Glycoinformatics. In Essentials of Glycobiology; Varki A., Cummings R. D., Esko J. D., Stanley P., Hart G. W., Aebi M., Darvill A. G., Kinoshita T., Packer N. H., Prestegard J. H., et al. , Eds.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Aoki-Kinoshita K.; Agravat S.; Aoki N. P.; Arpinar S.; Cummings R. D.; Fujita A.; Fujita N.; Hart G. M.; Haslam S. M.; Kawasaki T.; et al. GlyTouCan 1.0 – The International Glycan Structure Repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44 (D1), D1237–D1242. 10.1093/nar/gkv1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiemeyer M.; Aoki K.; Paulson J.; Cummings R. D.; York W. S.; Karlsson N. G.; Lisacek F.; Packer N. H.; Campbell M. P.; Aoki N. P.; et al. GlyTouCan: An Accessible Glycan Structure Repository. Glycobiology 2017, 27 (10), 915–919. 10.1093/glycob/cwx066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita A.; Aoki N. P.; Shinmachi D.; Matsubara M.; Tsuchiya S.; Shiota M.; Ono T.; Yamada I.; Aoki-Kinoshita K. F. The International Glycan Repository GlyTouCan Version 3.0. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 8, D1529–D1533. 10.1093/nar/gkaa947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumer-Bayraktar Z.; Nguyen-Khuong T.; Jayo R.; Chen D. D. Y.; Ali S.; Packer N. H.; Thaysen-Andersen M. Micro- and Macroheterogeneity of N -Glycosylation Yields Size and Charge Isoforms of Human Sex Hormone Binding Globulin Circulating in Serum. PROTEOMICS 2012, 12 (22), 3315–3327. 10.1002/pmic.201200354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]