In IDH-wildtype glioblastomas which meet the histopathological or molecular diagnosis criteria, it remains unclear whether the presence of TERT promotor mutations provides additional prognostic information. Based on a multicenter cohort of 466 IDH-wildtype glioblastomas (including 396 with and 70 patients without TERT promotor mutations), we found that TERT promotor mutations were neither associated with progression-free survival nor overall survival. This held true in various treatment-based or molecular subgroups. This argues against standardized analysis for TERT promotor mutation status for the purpose of prognostic or therapeutic relevance in newly diagnosed IDH-wildtype glioblastoma that otherwise meets the histopathological and molecular diagnosis criteria.

The WHO 2021 classification restricts the diagnosis of “glioblastoma WHO grade 4” to IDH-wildtype astrocytic gliomas either with (1) classical histopathological hallmarks or (2) qualifying molecular features.1 The latter include EGFR amplification, +7/−10 genotype, and TERT promotor mutation which are all associated with less favorable outcome when observed in combination with IDH-wildtype status.2,3 The presence of one of these three markers allows the diagnosis of “molecular” glioblastoma even when tumors appear histologically lower grade, and 80% of glioblastomas exhibit TERT promotor mutations.4 Whether TERT promotor mutations are of prognostic value in IDH-wildtype glioblastomas which otherwise yet fulfill the diagnostic (histopathological or molecular) criteria for glioblastoma is unclear. Here, we explored such an association based upon a well-annotated glioblastoma cohort from 7 international neuro-oncological centers participating in the RANO resect group.

With approval of the ethics committee of the Ludwig-Maximilians-University (Munich, Germany; AZ-21-0996), the RANO resect group compiled a retrospective database of newly diagnosed IDH-wildtype glioblastomas treated between 2003 and 2022 with a follow-up of ≥3 months.5 For the current study, individuals were selected when information on TERT promotor mutation status was available for review. Demographics, molecular information, clinical data, and outcome were extracted; and date of progression was determined per RANO criteria.

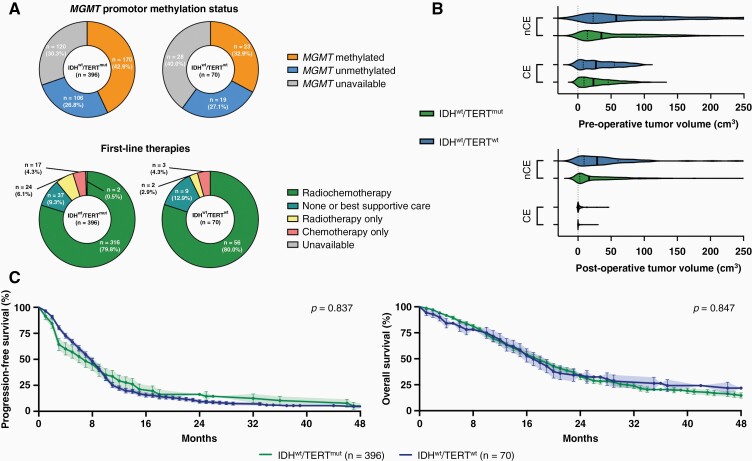

Among 1008 IDH-wildtype glioblastomas WHO grade 4, TERT promotor status was available in 466 patients including 396 individuals with (IDHwt/TERTmut) and 70 patients without TERT promotor mutations (IDHwt/TERTwt). Diagnosis rested upon IDH-wildtype combined with histopathological findings in 372 IDHwt/TERTmut (93.9%) and 65 IDHwt/TERTwt patients (92.9%); and was established based on the molecular signature (TERT promotor mutation for IDHwt/TERTmut; EGFR amplification for IDHwt/TERTwt) in the absence of classical histological findings in the remaining patients. Three hundred and fifty-eight IDHwt/TERTmut (90.4%) and 63 IDHwt/TERTwt patients (90%) underwent microsurgical resection, whereas the remaining had biopsy for tissue-based diagnosis. There were no differences in MGMT promotor methylation status, first-line therapy, or pre- and postoperative tumor volumes (both for contrast-enhancing and noncontrast-enhancing tumor) between IDHwt/TERTmut and IDHwt/TERTwt patients (Figure 1A and B). Median progression-free survival was 8 months and overall survival was 18 months at a median follow-up time of 36 months (IDHwt/TERTmut vs IDHwt/TERTwt: 33 vs 52 months; HR: 1.50, CI: 1.0–2.3). When patients were stratified according to TERT promotor mutation status, no outcome differences were detected for progression-free survival (IDHwt/TERTmut vs IDHwt/TERTwt: 7 vs 8 months; HR: 1.03, CI: 0.8–1.4) or overall survival (IDHwt/TERTmut vs IDHwt/TERTwt: 18 vs 17 months; HR: 0.97, CI: 0.7–1.3) (Figure 1C). Also, no association between survival and TERT promotor mutation status was found in the subgroups of patients with MGMT promotor methylation (HR for IDHwt/TERTwt: 0.99, CI: 0.6–1.8), unmethylated MGMT promotor status (HR for IDHwt/TERTwt: 0.92, CI: 0.5–1.7), first-line radiochemotherapy per EORTC 26981/22981 (HR for IDHwt/TERTwt: 1.00, CI: 0.7–1.4), or classical histopathological findings of glioblastoma (HR for IDHwt/TERTwt: 1.06, CI: 0.8–1.5).

Figure 1.

Clinico-molecular markers and outcome in IDH-wildtype glioblastoma with or without TERT promotor mutations. (A) Distribution of MGMT promotor methylation status (upper panel) and first-line therapies following surgery (lower panel) in IDH-wildtype glioblastomas with (IDHwt/TERTmut; n = 396) or without TERT promotor mutations (IDHwt/TERTwt; n = 70). (B) Pre- (upper panel) and postoperative tumor volumes (lower panel) in cm3 among IDH-wildtype glioblastomas undergoing microsurgical tumor resection with (IDHwt/TERTmut; n = 358; green) or without TERT promotor mutations (IDHwt/TERTwt; n = 63; blue). Volumes are indicated for contrast-enhancing (CE) and noncontrast-enhancing (nCE) tumor tissue. Median ± interquartile range. (C) Kaplan–Meier estimates of progression-free survival (left) and overall survival (right) for IDH-wildtype glioblastomas with (green line) or without TERT promotor mutations (blue line). Points indicate deceased or censored patients; light shadings indicate SEM.

We did therefore not find evidence that TERT promotor status adds prognostic information in IDH-wildtype glioblastomas exhibiting classical histopathological hallmarks (or other mutations) sufficient for glioblastoma diagnosis. This is in line with previous reports on IDH-wildtype glioblastomas,4,6,7 although these studies have either not controlled for clinical and molecular confounders4,6 or were substantially limited in sample size.4,7 Notably, IDHwt/TERTwt glioblastomas may identify a subset with a distinct (epi-)genetic and molecular profile compared to IDHwt/TERTmut tumors and may benefit from different, personalized treatment strategies.2,4,6 These biological findings, however, to date do not result in different clinical outcomes. Thus, up to now our retrospective data argue against standardized analysis for TERT promotor mutation status for the purpose of prognostic or therapeutic relevance in newly diagnosed IDH-wildtype glioblastoma that otherwise meets the histopathological and molecular diagnosis criteria. This might change in the future whenever TERT-directed therapies emerge.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the patients who contributed to the results of this study.

Contributor Information

Philipp Karschnia, Department of Neurosurgery, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich, Germany; German Cancer Consortium (DKTK), Partner Site Munich, Munich, Germany.

Jacob S Young, Department of Neurosurgery & Division of Neuro-Oncology, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA.

Antonio Dono, Department of Neurosurgery, McGovern Medical School at UT Health Houston, Houston, Texas, USA.

Levin Häni, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany.

Stephanie T Juenger, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany.

Tommaso Sciortino, Division for Neuro-Oncology, Department of Oncology and Hemato-Oncology, University of Milan, Milan, Italy.

Francesco Bruno, Division of Neuro-Oncology, Department of Neuroscience, University of Turin, Turin, Italy.

Nico Teske, Department of Neurosurgery, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich, Germany; German Cancer Consortium (DKTK), Partner Site Munich, Munich, Germany; Department of Neurosurgery, McGovern Medical School at UT Health Houston, Houston, Texas, USA.

Ramin A Morshed, Department of Neurosurgery & Division of Neuro-Oncology, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA.

Alexander F Haddad, Department of Neurosurgery & Division of Neuro-Oncology, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA.

Yalan Zhang, Department of Neurosurgery & Division of Neuro-Oncology, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA.

Sophia Stoecklein, Department of Radiology, University Hospital, LMU Munich, Munich, Germany.

Michael A Vogelbaum, Department of NeuroOncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, Florida, USA.

Juergen Beck, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany.

Shawn Hervey-Jumper, Department of Neurosurgery & Division of Neuro-Oncology, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA.

Annette M Molinaro, Department of Neurosurgery & Division of Neuro-Oncology, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA.

Roberta Rudà, Division of Neuro-Oncology, Department of Neuroscience, University of Turin, Turin, Italy; Division of Neurology, Castelfranco Veneto and Treviso Hospital, Treviso, Italy.

Lorenzo Bello, Division for Neuro-Oncology, Department of Oncology and Hemato-Oncology, University of Milan, Milan, Italy.

Oliver Schnell, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany.

Yoshua Esquenazi, Department of Neurosurgery, McGovern Medical School at UT Health Houston, Houston, Texas, USA.

Maximilian I Ruge, Department of Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery, Centre for Neurosurgery, University Hospital Cologne, Cologne, Germany.

Stefan J Grau, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany; Klinikum Fulda, Academic Hospital of Marburg University, Fulda, Germany.

Martin van den Bent, Department of Neurology, Erasmus MC Cancer Institute, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

Michael Weller, Department of Neurology, University Hospital and University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland.

Mitchel S Berger, Department of Neurosurgery & Division of Neuro-Oncology, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA.

Susan M Chang, Department of Neurosurgery & Division of Neuro-Oncology, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA.

Joerg-Christian Tonn, Department of Neurosurgery, Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich, Germany; German Cancer Consortium (DKTK), Partner Site Munich, Munich, Germany.

Funding

No funding to report.

Conflict of interest statement. M.W.—research grants: Quercis and Versameb. Honoraria/advisory board participation/consulting: Bayer, Medac, Merck (EMD), Nerviano, Novartis, Novocure, Orbus, and Philogen. M.A.V.—indirect equity/patient royalty interests: Infuseon Therapeutics. Honoraria: Celgene, Tocagen, and Blue Earth Diagnostics. Ni.Ta.—research grants: Medtronic; founder: BrainDynamics; advisory board: Nervonik and BrainGrade. R.R.—honoraria/advisory board/consulting: UCB, Bayer, Novocure, and Genenta. M.v.d.B.—consultant: Celgene, BMS, Agios, Boehringer, AbbVie, Bayer, Carthera, Nerviano, and Genenta. J.-C.T.—research grants: Novocure and Munich-Surgical-Imaging; royalties: Springer Publisher Intl. P.K., J.S.Y., A.D., L.H., T.S., F.B., S.T.J., Ni.Te., R.A.M., A.F.H., Y.Z., S.S., J.B., S.H.-J., A.M.M., L.B., O.S., Y.E., M.I.R., S.J.G., M.S.B., and S.M.C.—none.

Authorship Statement

Study concept/design: P.K. and J.-C.T. Data collection: P.K., J.S.Y., A.D., L.H., T.S., F.B., S.T.J., Ni.Te., R.A.M., A.F.H., Y.Z., S.H.-J., M.I.R., R.R., L.B., O.S., Y.E., S.J.G., A.M.M., M.S.B., S.M.C., and J.-C.T. Analysis/interpretation: P.K., S.M.C., M.v.d.B., and J.-C.T. Manuscript drafting: P.K., M.W., S.M.C., M.v.d.B., and J.-C.T. Manuscript revising: P.K., J.S.Y., A.D., L.H., T.S., F.B., S.T.J., Ni.Te., R.A.M., A.F.H., Y.Z., S.S., M.W., M.A.V., J.B., Ni.Ta., S.H.-J., A.M.M., R.R., L.B., O.S., Y.E., M.I.R., S.J.G., M.S.B., S.M.C., M.v.d.B., and J.-C.T.

References

- 1. Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, et al. . The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(8):1231–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stichel D, Ebrahimi A, Reuss D, et al. . Distribution of EGFR amplification, combined chromosome 7 gain and chromosome 10 loss, and TERT promoter mutation in brain tumors and their potential for the reclassification of IDHwt astrocytoma to glioblastoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2018;136(5):793–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arita H, Yamasaki K, Matsushita Y, et al. . A combination of TERT promoter mutation and MGMT methylation status predicts clinically relevant subgroups of newly diagnosed glioblastomas. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2016;4(1):79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Diplas BH, He X, Brosnan-Cashman JA, et al. . The genomic landscape of TERT promoter wildtype-IDH wildtype glioblastoma. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Karschnia P, Young JS, Dono A, et al. . Prognostic validation of a new classification system for extent of resection in glioblastoma: a report of the RANO resect group. Neuro Oncol. 2022. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noac193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu EM, Shi ZF, Li KK, et al. . Molecular landscape of IDH-wild type, pTERT-wild type adult glioblastomas. Brain Pathol. 2022:e13107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gramatzki D, Felsberg J, Hentschel B, et al. . Telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter mutation- and O(6)-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase promoter methylation-mediated sensitivity to temozolomide in isocitrate dehydrogenase-wild-type glioblastoma: is there a link? Eur J Cancer. 2021;147:84–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]