Abstract

Background

Although research demonstrates the necessity of social recovery capital (SRC) for youth in recovery, through having family that do not use substances and who support their recovery, the ways in which parents actually enact SRC have not been empirically examined. This qualitative study applied the Recovery Capital Model for Adolescents to group interview data from parent(s) of youth who resolved a substance use disorder (SUD) to explore the ways parents enacted SRC.

Method

The interviews were conducted in a prior ethnographic study in which parents of alternative peer group (APG) alumni volunteered to participate in a group interview; five mothers and five fathers of APG alumni participated in the interviews (n=10). Three investigators analyzed the interview transcripts using the constant comparative method to identify family SRC and the specific components parents supported their child’s recovery.

Results

The primary themes of parent support of SRC included locus of control, parent growth, and sober/supportive home. Locus of control included parent strategies to leverage youth’s participation in treatment/recovery. Parent growth focused on the process of change parents described: from denial to developing insight and learning how to parent a child in addiction. Supportive and structured family included time spent with youth in recovery-related activities and improved communication and relationships.

Conclusions

Together, these themes suggest a process of parent change that supports an adolescent’s recovery trajectory and increases parenting skills and coping. These themes also highlight how the APG structure enabled this process, generating potential hypotheses for future recovery-oriented research to address.

Keywords: Adolescent, Alternative Peer Group, Parenting, Qualitative Research, Recovery, Recovery Capital

Background

Parenting during adolescence requires a different set of approaches than used for younger children, and parents of youth with a substance use disorder (SUD) need an additional set of skills (Kirby et al., 2015; Mathibela & Skhosana, 2021). Parents are often initially unaware of their child’s substance use behaviors but eventually discover it in several ways (Choate, 2015): accidental (e.g., finding paraphernalia), abrupt (e.g., experiencing a child’s overdose), or a result of observing negative behaviors, followed by investigation and discovery (e.g., large drops in school grades or attendance). Addiction among children severely disrupts family functioning, yet parents may minimize its relevance unless they are forced to understand the gravity of the situation, such as through the result of criminal activity and justice involvement (Choate, 2015; Kirby et al., 2015).

A parent’s role in adolescent development to emerging adulthood is critical. As adolescents make this transition from childhood to emerging adulthood, they still need a variety of tangible and intangible supports, most of which should be available from their adult caregivers. For example, these developmental supports include receiving finances to participate in various activities, transportation to work/school/activities, help with developing time management and other life skills, and emotional support. Parents of youth in recovery are often additionally responsible for ensuring youth enter treatment and engage in the appropriate level of recovery supports, for example, by advocating for and coordinating services (Choate, 2015). Alternatively, parent behaviors and skills, such as their own coping and substance use, may jeopardize their child’s recovery (Hamilton et al., 2020). Indeed, outpatient treatment that involves the families in the therapeutic process has been shown to produce better results for youth than treatments without family involvement (Tanner-Smith et al., 2013). Exactly how these broader concepts are enacted by parents on a day-to-day basis, however, remains murky. This study aimed to address this gap by exploring specific ways parents acted to support their child’s recovery to ultimately better understand how to improve supports for families in this process.

Recovery Capital, the Alternative Peer Group, and Families

The Recovery Capital for Adolescents Model (RCAM) is based on an ecological model that identifies domains of resources that youth can use in the recovery process (Hennessy, 2017): human recovery capital (e.g., motivation, coping skills), financial recovery capital (e.g., insurance that covers treatment, stable living environment), social recovery capital (e.g., sober and supportive friends and family), and community recovery capital (e.g., continuing care supports in the community). Social recovery capital in particular is proposed as a key component of successful recovery as it focuses on the support – relational as well as recovery-specific – that one has in their lives. There is a strong body of evidence to suggest that positive and helpful relationships with individuals who are not using substances are highly predictive of sustained recovery and that two types of social relationships are key for youth: parents and same-age peers.

Recovery capital models suggest that this process of building capital occurs over time and in tandem with the recovery process (Granfield & Cloud, 1999, 2001; Hennessy, 2017). For example, by engaging in activities with a supportive (sober) social network, youth may learn motivation and coping skills (i.e., human capital) that can aid their recovery. Furthermore, as these skills are developed, youth are likely to further participate in supportive networks (social capital), which generate additional recovery resources. Indeed, recent arguments suggest that human recovery capital is primarily generated through having strong social and community recovery capital as these interpersonal and contextual factors provide a strong foundation for individuals to grow and thrive (Best & Ivers, 2021).

The process of adolescent SUD recovery is tumultuous, with a high likelihood of returning to use closely following treatment. As a result, many communities offer continuing care supports (i.e., a form of community capital) to serve youth during the vulnerable post-treatment period. One such program is the alternative peer group (APG; (Collier et al., 2014; Nash et al., 2015; Nelson et al., 2015)). APGs vary yet operate with several key components. First, APGs seek to create a recovery-supportive peer environment by offering youth-focused programming in a structured, adult-led environment that creates numerous opportunities for sober fun. Second, APGs facilitate group and individual counseling to provide clinical support to youth. Third, APGs incorporate parent and family programing, such as family group meetings or parent skill building sessions (Collier et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2020). The APG includes such programming to improve family functioning and support so that youth feel safe and supported in their recovery in the key developmental space of their home environment.

Aims.

A previous ethnographic study examined how APG alumni, their parents, and APG organizational leaders constructed the process of adolescent recovery from SUD in an APG (Nash et al., 2015). The findings from that study suggested that the process of adolescent recovery was a quest-like “journey” consisting of iterative phases that may or may not involve relapse. Fun, structured activities, and a sense of belonging through the APG helped youth develop strong relational ties with recovery role models, which inspired intrinsic motivation for recovery. These relationships were critical for navigating the rigorous, extended process. Leaders also cited family participation and support as crucial for success. The interviewed alumni similarly described family support as a necessary component of their recovery. As a result of these findings and the gaps in our understanding of family involvement in the post-treatment recovery process among youth, we aimed to answer the following research question: In what ways do parents participate in the recovery process, and how do they describe this participation, through the community recovery capital mechanism of the APG? Thus, in this study, we examined qualitative interview data from the parents of young adult APG alumni participants of that study by applying the RCAM model. Using these data, we examined parents’ statements on the process of their child’s recovery and identified the components of social recovery capital that they used to support their child as well as ways the APG, as a source of community recovery capital, supported their involvement.

Methods

Sampling

The ethnographic study that generated these data included intensive observations in the APG over a 20-month period and purposive sampling of young adults who had graduated from the APG and considered themselves to be in recovery from adolescent SUD, APG alumni (Green & Thorogood, 2018). The aim of that original study was to explore the process of recovery from adolescent SUD in an APG. Thus, the researcher sought to interview young people who had participated in an APG and showed evidence of a strong recovery trajectory. The APG director served as a key informant and provided a list of people who met those criteria from whom participants were recruited. There were 14 young adult participants, all of whom self-identified as being in recovery. They averaged 4.5 years (range 1–10 years) since their last use of substances, 50% were currently employed as recovery coaches or counselors in an APG, all reported strong relational ties with friends in recovery, and all reported active participation in recovery support meetings. Parents of the APG alumni who participated in the ethnography were also invited to join a “mothers” or “fathers” group interview and the resulting transcripts from those group interviews were analyzed for the current study. Group interviews were used given resource constraints of the study and to maximize parent availability. Of the 14 youth participants, eight had parents who volunteered (10 parents in total: five mothers participated in the mothers’ group interview and five fathers participated in the fathers’ group interview). All were white. Among the mothers, two were college graduates, two were high school graduates and one had less than a high school education. Among the fathers, all had college and/or post-graduate experience.

Youth in the program had specific requirements to meet for graduating from the APG. Family was also a primary focus of this APG: the parents were required to attend one APG social event each month and at least 12 weekly sessions of moms/dads support groups. The APG also encouraged participation in multi-family groups which were held weekly, parent support groups, individual family counseling, and involvement in outside 12-step programs (such as Al-Anon) so they might also benefit from working the 12 steps with a sponsor.

Data Collection

The semi-structured group interviews were audio-recorded. The interviews aimed to solicit parents’ perceptions of the process of recovery and critical elements that contributed to their child’s recovery. One researcher asked six main questions with a variety of follow-up prompts. The appendix includes the full guide (Section 1), but some examples of questions used are as follows: (1) What do you feel was (were) the important elements that led to your child finally making the turn towards recovery? And (2) What changed in you?.

Researcher Positionality, and Trustworthiness

Our team had diverse experiences related to recovery for this project. Although all have studied youth recovery in some capacity, only one of the authors was involved in the original data collection which involved observations. To increase the trustworthiness of the analysis (Lincoln & Guba, 1986), two members of the coding team reviewed the transcripts and applied initial codes, then reflected these back to the ethnographer for clarity and understanding. This iterative process was undertaken throughout the analysis. Three of the team members are parents themselves, an aspect that was discussed during many of the coding discussion meetings to reduce our own projections onto the data. Throughout this process we engaged in writing memos that were then used to inform our discussions.

Analysis

The coding process involved four iterative rounds and used both inductive and deductive approaches (Green & Thorogood, 2018; Huberman et al., 2014). As we were primarily interested in social recovery capital (SRC) and specific components of SRC used by parents for this study, we began with a code matrix developed in a prior study that applied the four dimensions of the RCAM model to interviews with youth who were actively participating in an APG (Nash et al., 2019). We initially used the entire code matrix to explore possible thematic interactions between SRC and other codes in a round of deductive coding. The code matrix was subsequently adapted through several rounds of inductive coding. The appendix includes the code matrix and description of the coding rounds (Sections 2 and 3). After the interviews were coded, we compared codes and, through discussion, grouped the excerpts related to social recovery capital into three relevant themes with several sub-themes.

All discrepancies were resolved via discussion. We did not calculate inter-rater reliability because it would not be accurate due to the constant calibration during the coding process. For the individual quotes presented in this manuscript, participants were given a unique identifier to indicate their interview group (M = Mother, F = Father) followed by “Sp” and their speaker number (1–5).

Results

Social Recovery Capital Components used by Parents

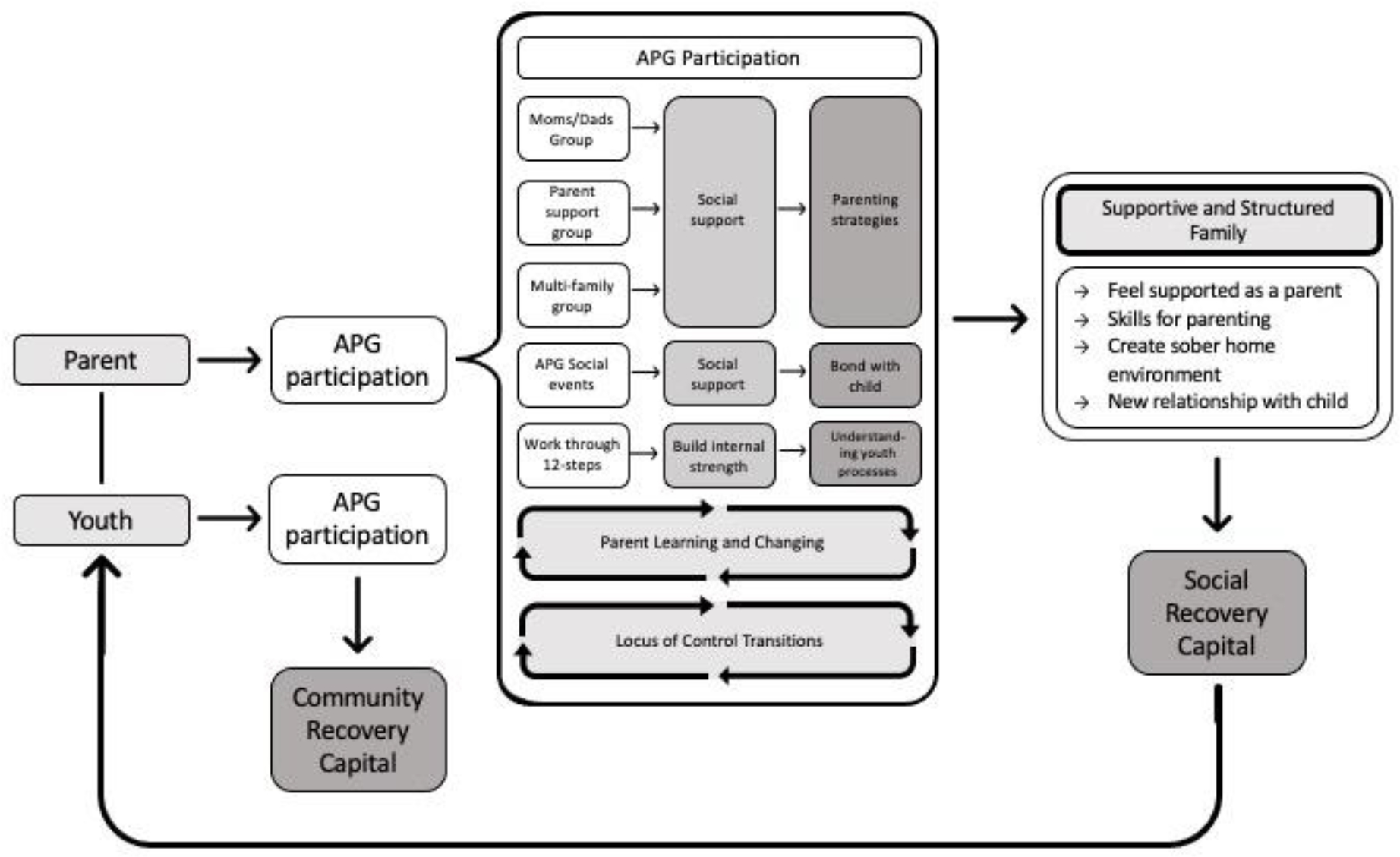

Parent’s description of their experience with their child’s recovery is complex and represents a process involving the community outside their home; these changes did not occur in a vacuum but seemed in large part due to the multiple structures in place by the APG. The parents described a process of their own change directly encouraged and facilitated by the APG: they reported that they did not initially know how to do all the things they needed to fully support their child. That is, through their involvement in the multi-family group meetings, moms/dads support groups, and social events provided by the APG, they learned how to structure their home environment, apply the right amount of pressure and support in their parenting of youth, and communicate with their child in a different way. Our resulting process model (Figure 1) depicts this parent process of change through the lens of how an APG and all its activities might guide and support parents in their own process of change which can then result in strengthened social recovery capital for their youth.

Figure 1.

A Model of Social Recovery Capital development among parents through an Alternative Peer Group

Note. APG = Alternative Peer Group.

To keep the focus on the parent process, this model does not include any direct sources of recovery capital gained by the youth as a result of their participation in the APG; yet, we acknowledge that youth receive a variety of recovery capital (and some would argue the majority of their recovery capital) through their own involvement in the APG.

Within this process model there were three primary themes related to parent involvement in building their child’s SRC through this involvement with the APG (Table 1, Section 4 in the Appendix includes a distribution of coded themes): (1) locus of control; (2) parent growth; and (3) supportive and structured family. Locus of control included a sub-theme of pressure from caregivers for services. Supportive and structured family had several sub-themes including time spent, parent leading/modeling recovery, communication and relationship, and safe home environment.

Locus of Control

The theme locus of control encompasses how the parents discussed their role in their child’s recovery process, including parents taking charge in making their child attend treatment and recovery activities and an understanding of their responsibilities versus their child’s responsibilities. As parents, many of them indicated they were the initial instigator of their child’s treatment (pressure from caregivers), and in most cases, determined how youth would engage in recovery services at various stages. Some parents gave their children a choice in where they would enroll in treatment or how the treatment process might progress, such as one father who describes that the decision to begin a 45-day inpatient detox “was a joint decision” (Sp2). Yet, once treatment was initiated, parents acknowledged that youth were responsible for continuing their recovery journey. This process is a delicate balance as parents learn skills for empowering their child to make responsible choices while simultaneously avoiding trying to control things that are out of their control.

MSp2: Right, right, and recognizing that I can’t control that [whether child relapses], so I can’t worry about it… I can’t go future tripping, you know, it doesn’t do any good.

Parent Growth

Parent reflections indicated that for their child’s recovery to be successful, they had to learn and grow along with their child – effectively being a model of change for their child. They described gaining deeper insight into themselves and to their child as they engaged in this process. An initial area of growth for both mothers and fathers was the need to develop awareness of the seriousness of their child’s SUD. They described realizing through the APG process how much their original denial had been an initial barrier in seeking help for their child.

MSp5: This can’t be my child; this doesn’t happen. I was angry. My husband and I were just going through a divorce. I was mad at him. I was mad at the money I had to spend to come here. I was mad at the travel time to get here. I mean, it was just a—it was the inconvenience of it all. It was just, I mean, it sounds so petty now. But I don’t think I realized the seriousness of the situation for a while. And then I had awareness. And that’s what changed. I got an awareness.

Fsp5: I think a lot of it for me was just cutting through all the denial and just kind of figuring out, this is serious stuff. And I knew it was; she’d disappear for three weeks at a time and you wouldn’t know where she was…. But at that point, you start to think, “Well, you know, it’s just, she’s young.” But finally, you know, police get involved, like he said, and it starts to get real serious real fast, thank goodness.

Fsp1: I think that’s a really excellent point that [Fsp5] made. And for me, I experienced the same kind of thing of, you know, the denial… And then, so I kept thinking, I can fix this. And I grew up in addiction, so I should’ve known better. But, you know, it was the getting out of the denial for me that was huge. And the realization that I was also part of the problem, you know, that my trying to fix this actually was contributing to this sort of dynamic and this sort of gravitational pull of chemical dependency and addiction.

As the denial cleared, parents discussed subsequently experiencing a variety of feelings including anger, shame, and guilt. As time went on and parents learned more about the nature of addiction and recovery through their involvement with the APG, they also learned to look for certain cues. First, many learned that addiction recovery is a process that often includes setbacks. They also had to learn about the deceptive nature that can accompany addiction.

MSp2: When he first relapsed, I was extremely angry because from my point of view, because he was in the midst of everything he could possibly have around him to support and help him… And then the deception—that just, I mean, it was the deception… But after I learned about relapse as a parent and an Al Anoner, and that many times it is, you know, a process, it’s part of the process, and that he was in his disease when that occurred back. So of course, they’re going to be deceptive. And so understanding that helped me work through that anger and not be, and put it behind me.

Participating in the parent programs was a necessary part of the process for their youth to remain in the APG; yet, many parents described it as initially uncomfortable, as they had to “expose” themselves and their vulnerabilities in the process. This was an element of learning and growth for them. Parents described that as they remained in the APG family groups, they found that the awkwardness eventually grew into a sense of belonging with other parents, a sort of “companionship of brokenness” (FSp1). Whereas initially they had felt shame, the sharing of similar stories bonded the parents to each other, providing some healing, and validation.

FSp5: Well, it just allows you to feel like, you know, you’re not the worst dad in the world….

FSp2: Well, when you say that, I guess I kind of forgot about that, was that you know, going into this is, you know, we’re such failures as parents. And, you know, finally accepting the fact that, you know—you can always do something better, right? But what you did, did not make that person necessarily do that.

Supportive and Structured Family

The theme supportive and structured family broadly represents how parents provided a supportive environment for recovery, often created through their involvement in the recovery process and the APG activities. Parents gave a variety of examples of how they supported their children, including recognizing the problem and taking action with their child as well as making changes to their own substance use (safe home environment, parent leading/modeling recovery), spending time in the APG activities and transporting their child places (time spent), and encouraging and communicating better with each other (relationship).

One primary role the parent served was recognizing the problem and taking the steps they felt necessary to get help for their child. Sometimes this meant a difficult conversation about the reality they faced and the fact that they needed outside help.

MSp1: He said, “You know, I just really don’t think I want to go back to that place and be around those, the people like that.” And I said, “You mean the people just like you?” (laugher) He really didn’t have an answer for that. But I said, “You know, we have to, we just have to go. We’re, our family’s a mess.”

FSp1: And I just said to him, “you know, we’ve got to do something different because this isn’t working”. And he kept saying, “Dad, you and I could do this together; we can do this together.” And I said, “I can’t help you anymore, I just can’t. I can’t, I don’t know how, and so we have to do something different. And that means I have to do something different too.”

Parents described their own need to stop using substances to support their child’s process. Some also described the knowledge they developed through working the 12-step program of recovery which they could then apply to improve their parenting process.

MSp2: I kind of found some serenity through working my own steps. And I recognized my codependency, my codependency behaviors… That I didn’t see before.

The fathers group also discussed knowing when and how to advocate for their child, including when other professional adults in contact with their child “fail”. One example several participants discussed was the need to make sure the child’s other healthcare professionals knew to avoid prescribing addictive pain medications (e.g., for wisdom tooth surgery). Parents also felt that supporting their child meant active support and attendance in the available APG programming and that youth would be more likely to participate if they knew their parent was a part of the process.

MSp4: [Child] was definitely not ready when she came in. And I think she realized we were serious—there was no getting out of it. So, she needed to apply herself towards that. We were attending all the meetings and she knew that I was taking my lunch break at work to go pick her up, bring her [to APG]. So, I think there was the external pressure. And then once she got in with the group, you know, talking and listening to the stories… I think that’s what helped her.

FSp1: It seems to me that the kids where the families are really struggling or they don’t show up. I mean, the biggest part is to show up. But their parents aren’t showing up, and they don’t have the support, and it doesn’t carry through, or it’s not consistent—those kids have the hardest time.

Parents acknowledged that as a result of their child’s recovery process and their own personal changes, overall communication with their child improved as did their relationships. One mother contrasted the “chaos” of having a child in active addiction with the peace that comes with recovery. Along these lines, parents discussed having “real” communication between themselves and their child even when the communication was a disagreement and that the APG in particular had taught them ways to “fight fair” (FSp1).

Discussion

This study demonstrated how parents of youth who successfully graduated from an APG program engaged in their own processes of change that supported the development of social recovery capital for their children. A wide variety of research investigates different aspects of recovery capital for youth, including human and financial recovery capital (Hamersma & Maclean, 2018; Hamilton et al., 2020; Hennessy, 2018; Hennessy & Finch, 2019; Skogens & von Greiff, 2020), as well as peer and friend elements of recovery and social recovery capital (Nash et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2020; Viverette et al., 2020). This is the first study that identifies specific ways that parents within an APG were supported and as a result, had positive changes in their own lives and behaved in ways to better support their child’s recovery. These findings are in line with recent suggestions of a trickle-down effect of social and community recovery capital; where a context is created to support recovery, many can benefit (Best & Ivers, 2021).

From these parents’ perspectives, extensive family changes occur alongside youth changes during the recovery process. Families, and specifically the heads of those families, must reorient the household to support a child pursuing recovery. This initially involves identifying the problem and taking action to get the child engaged in treatment. Yet, the process for the family does not end there. These parents described developing insight through their active involvement in this process, a factor other research on recovery has indicated should be included in understanding recovery and developing recovery capital (Ivers et al., 2018). Parents also demonstrated how they reflected on and changed some of their own behaviors, ways of interacting with their child, and overall family functioning. Additionally, these parents indicated an ongoing process of shifting the locus of control between themselves and their child, supporting other research indicating a fine balancing act that parents must achieve (Cornelius et al., 2017).

Because these families were part of an APG, this process did not occur in isolation, extrinsic support that families acknowledged and appreciated (Brousseau et al., 2020). Similar to family therapy that targets these behaviors to produce positive changes for youth and their families, the APG model also incorporates activities to foster these changes in families, specifically through the parents (Hogue et al., 2021). Thus, for these parents and youth, the APG served as a community recovery capital resource that facilitated a menu of tools for improving social recovery capital that parents strongly felt were necessary for positive change. Given these findings, the structure of the APG model, and what the RCAM and other recovery-oriented research and theory suggests (Best & Ivers, 2021; Hennessy et al., 2018), we propose a model of how APGs, as a source of community recovery capital might enable both social and human recovery capital development (Figure 1). In this model, parent and youth involvement in the different APG activities could be examined over time in future research to address whether and how different components of the APG model influence the recovery process for youth and their families in a bidirectional manner. Further research is necessary to understand the exact pathways of change families derive from involvement in an APG as well as whether these changes trickle-out into broader collective community recovery efforts, such as challenging community stigma around addiction recovery (Best et al., 2017; Best & Ivers, 2021).

Limitations

Despite the small sample size, this work contributes novel understanding about parent components of the adolescent recovery process by exploring parent perceptions of their child’s recovery process and their role in it. Yet, we advise caution in generalizing these findings beyond adolescents, for youth in residential settings, or for communities where there is not such an extensive linkage between treatment and aftercare. As well, given the potential differences in perspectives among parents and their children about the same process, future adolescent recovery research should collect and examine perspectives from children, their parents, and other key family members, to understand how they may (or may not) work together to facilitate the recovery experience.

Furthermore, this sample of parents had children who were now considered in long-term recovery and were highly engaged in their child’s recovery process. Their race (all white) and education characteristics could have led to higher access to these services and to being able to engage in the process as much as they did. Research has demonstrated the difficulty in retaining parents in care, even care meant to support their wellbeing while dealing with their child’s substance use issues (Ameral et al., 2020); thus, the findings may not generalize to parents who are less engaged in the process or who may not have the financial recovery capital resources to do so.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that the APG as a community recovery capital resource provides a valuable set of supports for parents which can contribute to the building of youth social recovery capital where both may then benefit. The parent interviews suggest that APG activities cultivate parenting skills, a deeper understanding of the recovery process, and overall family functioning. Our proposed model of how APGs could lead to the development of recovery capital among parents and their child (Figure 1) is the first step at systematizing that process and could be used to guide future examinations of recovery capital development through the APG or similar adolescent recovery-oriented services that engage families.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The original data for this study was supported in part by grants to Angela Nash from the NAPNAP Foundation and the Zeta Pi Chapter of Sigma Theta Tau and the Hogg Foundation for Mental Health RRU-013. Emily Hennessy has support from NIAAA (K01 AA028536). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the NIAAA or the other funding sources. We would like to the acknowledge the APG staff, alumni, and parents who participated in the ethnography for sharing their time and reflections on their experience.

Footnotes

Declarations of Interest: No conflict declared

References

- Ameral V, Yule A, McKowen J, Bergman BG, Nargiso J, & Kelly JF (2020). A naturalistic evaluation of a group intervention for parents of youth with substance use disorders. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 38(3), 379–394. 10.1080/07347324.2019.1633978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best D, Irving J, Collinson B, Andersson C, & Edwards M (2017). Recovery Networks and Community Connections: Identifying Connection Needs and Community Linkage Opportunities in Early Recovery Populations. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 35(1), 2–15. 10.1080/07347324.2016.1256718 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Best, & Ivers. (2021). Inkspots and ice cream cones: A model of recovery contagion and growth. Addiction Research and Theory. [Google Scholar]

- Brousseau NM, Earnshaw VA, Menino D, Bogart LM, Carrano J, Kelly JF, & Levy S (2020). Self-perceptions and benefit finding among adolescents with substance use disorders and their caregivers: A qualitative analysis guided by Social Identity Theory of Cessation Maintenance. Journal of Drug Issues, 50(4), 410–423. 10.1177/0022042620919368 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choate P (2015). Adolescent Alcoholism and Drug Addiction: The Experience of Parents. Behavioral Sciences, 5(4), 461–476. 10.3390/bs5040461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier C, Hilliker R, & Onwuegbuzie A (2014). Alternative Peer Group: A Model for Youth Recovery. Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery, 9(1), 40–53. 10.1080/1556035x.2013.836899 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius T, Earnshaw VA, Menino D, Bogart LM, & Levy S (2017). Treatment motivation among caregivers and adolescents with substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 75, 10–16. 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granfield R, & Cloud W (1999). Coming Clean: Overcoming Addiction without Treatment (Vol. 25, Issue 4). New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Granfield R, & Cloud W (2001). Social context and “natural recovery”: The role of social capital in the resolution of drug-associated problems. Substance Use & Misuse, 36(11), 1543–1570. 10.1081/JA-100106963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J, & Thorogood N (2018). Developing qualitative research proposals. In Qualitative methods for health research (4th ed., pp. 49–82). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hamersma S, & Maclean JC (2018). Insurance Expansions and Children’s Use of Substance Use Disorder Treatment. Journal Article. 10.3386/w24499 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton SL, Maslen S, Best D, Freeman J, O’Donnell M, Reibel T, Mutch RC, & Watkins R (2020). Putting ‘Justice’ in Recovery Capital: Yarning about Hopes and Futures with Young People in Detention. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 9(2), 20–36. 10.5204/ijcjsd.v9i2.1256 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy EA (2017). Recovery capital: A systematic review of the literature. Addiction Research & Theory, 25(5), 349–360. 10.1080/16066359.2017.1297990 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy EA (2018). A latent class exploration of adolescent recovery capital. Journal of Community Psychology, 46(4), 442–456. 10.1002/jcop.21950 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy EA, Cristello JV, & Kelly JF (2018). RCAM: A proposed model of recovery capital for adolescents. Addiction Research & Theory, 1–8. 10.1080/16066359.2018.1540694 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy EA, & Finch AJ (2019). Adolescent recovery capital and recovery high school attendance: An exploratory data mining approach. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 33(8), 669–676. 10.1037/adb0000528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Schumm JA, MacLean A, & Bobek M (2021). Couple and family therapy for substance use disorders: Evidence-based update 2010–2019. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, epub. 10.1111/jmft.12546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huberman AM, Miles J, & Saldana MB (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (Third). SAGE Publications, Inc.,. [Google Scholar]

- Ivers JH, Larkan F, & Barry J (2018). A longitudinal qualitative analysis of the lived experience of the recovery process in opioid-dependent patients post-detoxification. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 50(3), 231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KC, Versek B, Kerwin ME, Meyers K, Benishek LA, Bresani E, Washio Y, Arria A, & Meyers RJ (2015). Developing Community Reinforcement and Family Training (CRAFT) for Parents of Treatment-Resistant Adolescents. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 24(3), 155–165. 10.1080/1067828X.2013.777379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, & Guba EG (1986). But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 1986(30), 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Mathibela F, & Skhosana RM (2021). I just knew that something was not right! Coping strategies of parents living with adolescents misusing substances. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 120, 108178–108178. 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash A, Marcus M, Engebretson J, & Bukstein O (2015). Recovery From Adolescent Substance Use Disorder: Young People in Recovery Describe the Process and Keys to Success in an Alternative Peer Group. Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery, 10(4), 290–312. 10.1080/1556035x.2015.1089805 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nash, Hennessy EA, & Collier C (2019). Exploring recovery capital among adolescents in an alternative peer group. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 199(1), 136–143. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JA, Henderson SE, & Lackey S (2015). Adolescent Recovery From Substance Use in Alternative Peer Groups: A Revelatory Case Study. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 6(2), 100–112. 10.1177/2150137815596044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skogens L, & von Greiff N (2020). Recovery processes among young adults treated for alcohol and other drug problems: A five-year follow-up. Nordisk Alkohol- & Narkotikatidskrift : NAT, 37(4), 338–351. 10.1177/1455072520936814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith NZ, Vasquez PJ, Emelogu NA, Hayes AE, Engebretson J, & Nash AJ (2020). The Good, the bad, and recovery: Adolescents describe the advantages and disadvantages of Alternative Peer Groups. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 14, 1178221820909354–1178221820909354. 10.1177/1178221820909354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner-Smith E, Wilson SJ, & Lipsey MW (2013). The comparative effectiveness of outpatient treatment for adolescent substance abuse: A meta-analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 44(2), 145–158. 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viverette A, Vasquez J, Moreno N, Ruelas R, & Gomez RJ (2020). A Gap in the Recovery Continuum: Is a San Antonio recovery high school the solution? Our Lady of the Lake University: Worden School of Social Service. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.