Abstract

An evaluation of the clinical outcome and the duration of the antibody response of patients with human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) was undertaken in Slovenia. Adult patients with a febrile illness occurring within 6 weeks of a tick bite were classified as having probable or confirmed HGE based on the outcome of serological or PCR testing. Thirty patients (median age, 44 years) were enrolled, and clinical evaluations and serum collection were undertaken at initial presentation and at 14 days, 6 to 8 weeks, and 3 to 4, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months. An indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) was performed, and reciprocal titers of ≥128 were interpreted as positive. Patients presented a median of 4 days after the onset of fever and were febrile for a median of 7.5 days; four (13.3%) received doxycycline. Seroconversion was observed in 3 of 30 (10.0%) patients, and 25 (83.3%) showed >4-fold change in antibody titer. PCR results were positive in 2 of 3 (66.7%) seronegative patients but in none of 27 seropositive patients at the first presentation. IFA antibody titers of ≥128 were found in 14 of 29 (48.3%), 17 of 30 (56.7%), 13 of 30 (43.4%), and 12 of 30 (40.0%) patients 6, 12, 18, and 24 months after presentation, respectively. Patients reporting additional tick bites during the study had significantly higher antibody titers at most time points during follow-up. No long-term clinical consequences were found during follow-up.

Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) is an emerging tick-borne disease described for the first time in 1994 in the United States (4). The first European case of acute HGE was uncovered in Slovenia in 1996 and reported in 1997 (20). Through September 2000, nine patients with acute HGE confirmed by positive PCR results and/or at least fourfold change in antibody titers contracted their illness in Central Europe, in Slovenia (15, 16, 24; S. Lotric-Furlan, M. Petrovec, T. Avsic-Zupanc, T. Lejko-Zupanc, and F. Strle, Abstr. II Croatian Congr. Infect. Dis. Int. Participation, abstr. 71, p. 30, 2000).

The epidemiology and ecology of HGE have not been completely elucidated. The etiological agent of HGE is closely related to the veterinary pathogen Ehrlichia phagocytophila, which has been a recognized cause of disease among ruminants in Europe for decades (25). In Europe, E. phagocytophila is transmitted by Ixodes ricinus ticks (21).

The clinical presentation of HGE is generally nonspecific and usually consists of fever, headache, malaise, myalgias, and/or arthralgias. A history of tick bite or tick exposure, while suggestive, is not diagnostic. Similarly, clinical laboratory findings of leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated liver enzymes are typical but relatively nonspecific, making the diagnosis problematic.

Infection with E. phagocytophila in the acute stage has been confirmed by identification of morulae in granulocytes, positive PCR results using whole blood as a substrate, and/or isolation of E. phagocytophila from the blood. Serological tests, particularly indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA), are commonly used but are often negative during the initial phase of the disease (10).

HGE is an acute disease. Chronic forms of the illness have not been documented, although ehrlichial DNA has been demonstrated in the convalescent blood of patients (11, 14). Data on the duration of serum antibody response after acute HGE are limited and are based entirely on reports from the United States (2, 5, 6).

The aim of this prospective study was to evaluate the clinical outcome of European patients with HGE and to document the duration of antibody response to the E. phagocytophila antigens.

(This study was presented in part at the 15th Meeting of the American Society for Rickettsiology, South Seas Plantation, Captiva Island, Fla., 30 April to 3 May 2000.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

The clinical aspects of this prospective study were conducted at the Department of Infectious Diseases, University Medical Centre, Ljubljana, Slovenia. Patients older than 15 years with acute febrile illness occurring within 6 weeks after a tick bite and laboratory evidence of infection with E. phagocytophila uncovered between March 1995 and December 1997 were eligible for inclusion in the study. Patients were referred by primary care physicians to our department for evaluation. Informed consent was obtained from all patients included in the study.

At the initial visit, epidemiological data and information about the course of the disease were obtained, and a physical examination was performed. The patients were reexamined at 14 days, 6 to 8 weeks, and approximately 3 to 4 months, 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, and 24 months after their first visit. Some examinations were missed by individuals.

Specimen and information collection.

At the initial visit, an acute-phase serum specimen and an EDTA-anticoagulated whole blood specimen were obtained for each patient. Sera were collected at follow-up visits. The patients were also questioned about the occurrence of additional tick bites during the interval since the onset of the initial febrile disease.

PCR assays.

Whole blood drawn at the patient's initial visit was examined. DNA was extracted from leukocytes separated from the blood in the buffy coat and was used as a template for PCR assays to detect DNA from the E. phagocytophila genogroup, as previously described (17). Both the 16S rRNA gene primers GE9f and GE10r and nested primer sets (HS1-HS6 followed by HS43-HS45) targeting the GroESL operon of ehrlichiae were used.

Serological testing.

Acute- and convalescent-phase serum samples were tested by IFA for the presence of specific antibodies to the E. phagocytophila antigens. Antigen was prepared from a human promyelocytic leukemia cell line (HL-60) infected with a tick-derived isolate of the HGE agent (USG3). Twofold dilutions of test sera were made in phosphate-buffered saline containing 1% bovine serum albumin and 1% goat serum to reduce background fluorescence, and an immunoglobulin G (γ-specific) conjugate was used to reduce nonspecific binding. Endpoint titers were recorded as the reciprocal of the last serial dilution at which specific apple-green fluorescence of ehrlichial inclusion bodies was focally located in the cytoplasm of the infected cells (18). Reciprocal IFA titers of ≥128 were interpreted as a positive finding (the cutoff value was based upon findings from well-characterized sera from patients with confirmed HGE and an uninfected control population). Serological tests were repeated at sequential examinations. For calculation of geometric mean titers (GMTs), titers of <32 (initial dilution tested) were given an arbitrary value of 4.

Case definitions.

A confirmed case of HGE was defined as a patient who developed an acute febrile illness within 6 weeks after a tick bite with laboratory findings of seroconversion (titers from <32 to ≥128) or a fourfold change in serum antibody titers to E. phagocytophila antigens and/or a positive PCR result with subsequent sequencing of the amplicons to demonstrate specific ehrlichial DNA. A probable case of acute HGE was defined as a patient who developed an acute febrile illness within 6 weeks after a tick bite with an IFA titer of ≥128 in acute- and convalescent-phase serum samples without demonstrating a fourfold change in titer (6, 17).

Statistical methods.

Patient data were analyzed using SPSS Version 10 for Windows (SPSS Corp., Chicago, Ill.). Differences between the GMTs of groups of patients were nonparametrically distributed and were assessed using the Mann-Whitney U test. For all analyses, a P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patients and confirmation of acute HGE.

Thirty patients were evaluated in this study (Table 1). The study cohort included 11 females and 19 males with a median age of 44 years (minimum-maximum, 19 and 71 years). The incubation period (the time from tick bite to the onset of the illness) ranged from 3 to 16 (median, 12) days. It was calculated for patients who recalled no more than one tick bite during the last 6 weeks prior to the first examination. Patients presented a median of 4 days (range, 2 to 14 days) after the onset of illness and were febrile for a median of 7.5 days (range, 3 to 21 days). Four (13.3%) patients were treated with doxycycline, and 13 of 30 (43.3%) patients were hospitalized (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographic and laboratory data for 30 Slovenian patients with confirmed or probable acute HGE

| Patient no. | Age (yr)/sexe | Duration of symptomsa | Antibody titer at initial examinationb | Peak titer | Antibiotic treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 70/Fc | 3 | Neg | 512 | NTd |

| 2 | 55/Fc | 7 | Neg | 1,024 | NT |

| 3 | 43/M | 5 | Neg | 256 | NT |

| 4 | 34/M | 4 | 256 | 2,048 | Doxycycline |

| 5 | 24/M | 3 | 256 | 256 | NT |

| 6 | 32/F | 3 | 1,024 | 2,048 | NT |

| 7 | 50/M | 2 | 128 | 256 | NT |

| 8 | 68/M | 10 | 128 | 256 | NT |

| 9 | 62/F | 4 | 128 | 128 | Doxycycline |

| 10 | 65/F | 7 | 256 | 256 | NT |

| 11 | 64/M | 4 | 256 | 512 | NT |

| 12 | 41/M | 5 | 256 | 256 | NT |

| 13 | 60/F | 2 | 256 | 256 | NT |

| 14 | 71/M | 5 | 256 | 512 | NT |

| 15 | 42/F | 4 | 256 | 256 | NT |

| 16 | 45/M | 6 | 1,024 | 1,024 | NT |

| 17 | 45/M | 2 | 512 | 512 | Doxycycline |

| 18 | 35/M | 3 | 512 | 512 | NT |

| 19 | 61/F | 4 | 256 | 256 | NT |

| 20 | 55/F | 14 | 256 | 256 | NT |

| 21 | 28/M | 14 | 512 | 512 | NT |

| 22 | 26/M | 7 | 8,192 | 8,192 | NT |

| 23 | 34/M | 8 | 256 | 512 | NT |

| 24 | 51/M | 3 | 512 | 512 | Doxycycline |

| 25 | 21/M | 2 | 512 | 1,024 | NT |

| 26 | 49/M | 2 | 8,192 | 8,192 | NT |

| 27 | 37/F | 3 | 128 | 256 | NT |

| 28 | 32/F | 2 | 256 | 256 | NT |

| 29 | 41/M | 4 | 512 | 512 | NT |

| 30 | 19/M | 4 | 1,024 | 1,024 | NT |

Time (in days) from the onset of symptoms to the initial examination.

IFA titer expressed as the reciprocal of the dilution. Neg, negative.

Patients in whom acute HGE was confirmed by positive PCR.

NT, not treated.

M, male; F, female.

Ten of 30 (33.3%) patients recalled having more than one tick bite within 6 weeks prior to the onset of their illness. At sequential examinations, 20 of 30 (66.7%) patients reported at least one tick bite during the follow-up period.

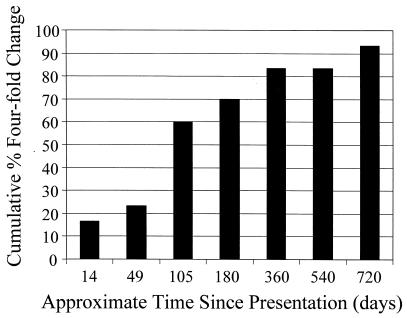

Twenty-eight patients (93.3%) fulfilled the criteria for confirmed HGE, and two met the criteria for probable acute HGE. Three patients seroconverted to E. phagocytophila during the first 2 weeks of the study, and 25 patients showed a fourfold change in titer during the first 24 months of the study (Fig. 1). PCR analysis with the 16S rRNA primers GE9f-GE10r and the GroESL primers generated products of the expected sizes (919 and 480 bp, respectively) from DNA extracted from blood samples obtained from two of the three patients with sera lacking antibody at their initial presentation (Table 1). None of the 27 patients with antibody at their initial presentation were PCR positive.

FIG. 1.

Cumulative percentage of patients demonstrating a fourfold change in antibody to E. phagocytophila by IFA and therefore meeting the criteria for confirmed HGE. Twenty-five of 30 (83.3%) patients met the criteria for confirmed HGE at 1 year of follow-up, and 28 of 30 (93.3%) patients met them by the second year.

Serological findings.

At presentation, antibody at titers of ≥128 was detected in 27 (90%) patients (GMT = 256) (Table 2). Seroconversion or fourfold elevation in serum antibody titers to E. phagocytophila antigens was observed in 4 (13.3%) patients, while 24 showed significant declines in titer over the study interval (Fig. 1).

TABLE 2.

Serological test results for patients with confirmed or probable acute HGE at selected time intervals after the onset of symptoms

| Time after initial visit | GMT | Median titer (range) | No. of positive patients/no. tested (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0a days | 256 | 256 (0–8,192) | 27/30 (90) |

| 14 days | 288 | 256 (128–8,192) | 23/23 (100) |

| 6–8 wk | 280 | 256 (0–8,192) | 28/29 (96.6) |

| 3–4 mo | 86 | 128 (0–8,192) | 20/30 (66.7) |

| 6 mo | 68 | 96 (0–8,192) | 14/29 (48.3) |

| 12 mo | 99 | 128 (0–1,024) | 17/30 (56.7) |

| 18 mo | 75 | 64 (0–2,048) | 13/30 (43.3) |

| 24 mo | 38 | 64 (0–1,024) | 12/30 (40.0) |

Antibody titers to E. phagocytophila antigens were determined at the initial visit.

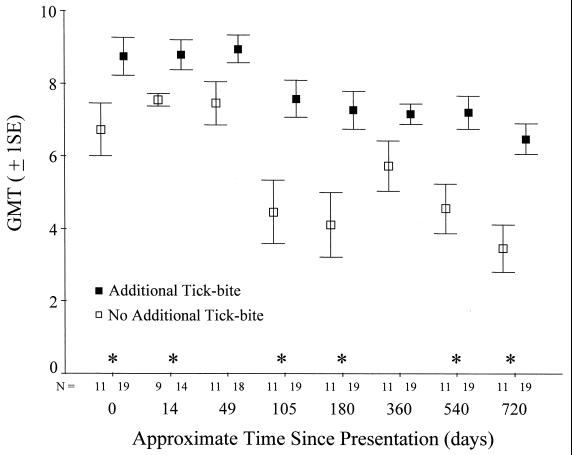

Peak antibody titers of ≥2,048 were found in 13.3% of the patients, peak antibody titers of ≥512 were found in 56.7% of the patients, and peak antibody titers of ≥256 were found in 96.7% of the patients. Peak titers among the majority of patients (26 of 30; 86.7%) occurred within 6 to 8 weeks of presentation. The highest GMT was found at the day 14 examination period; the GMT then declined during the observation period, although not monotonically (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Mean ± 1 standard error (SE) of the GMT (log2) for patients grouped by history of tick bites during the study follow-up period of 2 years. Although for illustration means ± 1 SE are shown, the asterisks indicate significant differences between the two groups based on a nonparametric statistical test (Mann-Whitney U test; P < 0.05). The small numbers on the x axis indicate the sample size in each group at each time point used in the analyses.

Persistence of antibodies and reported tick bites.

IFA antibodies to E. phagocytophila antigens in titers of ≥128 were present among 56.7% of the 30 patients followed for 1 year and among 40.0% of the patients followed for 2 years (Table 2). Individuals reporting additional tick bites during the study had significantly higher antibody titers than did the group of patients not reporting additional tick bites (P < 0.001; Fig. 2). The differences in antibody titers between these two groups were present at entry into the study and at most time points throughout the study (Fig. 2).

Clinical follow-up.

No long-term clinical consequences of acute HGE were identified during the 2 years of follow-up. There were no differences in clinical outcome between the patients with confirmed or probable HGE or between the four patients who had been treated with doxycycline and those who had not received antibiotics. Patients who reported additional tick bites during the follow-up period and entered the study with a higher GMT were indistinguishable in the duration of their symptoms prior to initial presentation from the group not reporting additional tick bites (P = 0.40; Mann-Whitney U test).

DISCUSSION

More than 600 patients with acute HGE have been identified in the United States and Europe (3). Reports from Europe comprise less than 25 patients; however, some of these reported cases do not fulfill the criteria for confirmed or probable HGE used in the present study (8, 15, 16, 19, 22, 24). The 30 Slovenian patients with confirmed or probable HGE whom we followed for 2 years constitute the largest patient cohort of this type reported from Europe.

None of the patients in our study demonstrated signs of chronic disease, which is consistent with previous findings from the United States (1, 6, 23). Whether ehrlichiae persisted in our patients beyond the acute stage is unknown. Unfortunately, we did not test whole blood for the presence of ehrlichial DNA after the first visit; two studies from the United States have reported persistence of ehrlichial DNA in a small number of asymptomatic persons who had recovered from HGE (11, 14).

In the United States, most patients have been treated with appropriate antibiotics, while most of our patients were not. However, it is not clear that the lack of doxycycline treatment contributed to disease severity among our cohort or influenced other study outcomes, such as antibody kinetics. The 43.3% of patients hospitalized in our Slovenian cohort was within the range of 56% (6) and 28% (1) reported from case series of HGE in the United States, where most patients received doxycycline therapy. The long-term outcome was favorable in all our patients regardless of antibiotic therapy.

The majority (93.3%) of our patients met the criteria for confirmed HGE. A fourfold change in antibody titer (increase or decrease) has been used in many studies of HGE (7, 11), and this criterion is recommended for use in the United States (9). Most of our patients had high levels of antibody at their initial presentation and then showed significant declines in antibody titer over the next few months of follow-up. The observation that most Slovenian patients (90%) had peak or high levels of antibody at their initial presentation is in contrast to the United States, where only about 50% of HGE patients (13) had antibody at presentation. This may indicate that some Slovenian patients were farther into their disease course than comparable patients in the United States. Such an explanation is consistent with the observation that the clinical course of HGE in Slovenia has been described as milder than that in the United States (6, 16).

The prevalence of PCR-positive samples in our study was low (2 of 30; 6.7%). However, 27 of the 30 patients tested by PCR were already seropositive, and PCR did show diagnostic value in patients who were seronegative at their initial examination (2 of 3 positive).

Information on the duration and kinetics of the antibody response following HGE is limited. Reports from the United States have shown that about 50% of patients with acute HGE (11 of 24 [5] and 5 of 10 [2]) had significant antibody titers 1 year after acute disease and 50% (5/10) of patients had antibody at 30 months (5). Our finding that 56.7% of HGE patients had antibody titers of ≥128 at 1 year and 40% had antibody titers of ≥128 after 2 years are very similar to the reports from the United States. However, direct comparisons of specific IFA results obtained in different studies should be interpreted with caution, as the results are influenced by the selection of different groups of patients, lack of standardization of test antigens and test conditions, and the inherent variability of serological testing conducted at different laboratories.

Although our patient cohort was small and comparisons across subgroups were limited, an unusual observation emerged. Patients reporting additional tick bites within the follow-up interval entered the study with significantly higher antibody titers and maintained significantly higher antibody titers than the group not reporting additional tick bites. An obvious potential contributing factor to the differences in antibody titer is a booster effect caused by exposure to additional bites from ticks transmitting E. phagocytophila. However, this booster effect should have primarily influenced titers during late follow-up visits and not GMTs during initial visits.

Little is known about reinfection with E. phagocytophila, although it has been documented in one case in the United States, where a 32-fold increase in antibody titer (from 80 to 2,560) occurred within 8 days of reinfection (12). Antigenically related organisms might also be present in ticks and give rise to cross-reactive antibodies in persons commonly bitten by ticks. Reinfection or previous exposure to a related ehrlichia could result in an anamnestic antibody response in persons with preexisting immunity, and these may be factors contributing to the patterns in antibody titers we observed in our patient cohort.

In conclusion, ehrlichial antibody was present in 40% of our patient cohort 2 years after their initial examinations. Although >90% of these individuals met the criteria for confirmed ehrlichiosis and few were treated with antibiotics, no long-term consequences of HGE were identified during clinical evaluations. The elevated antibody titers among patients reporting additional tick bites during the study interval may indicate some previous immunologic acquaintance with ehrlichial antigens.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant J3-8689 (F.S.) and grant L3-7916-381-95 (T.A.Z.) from the Ministry of Science and Technology of Slovenia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguero-Rosenfeld M E, Horowitz H W, Wormser G P, McKenna D F, Nowakowski J, Munoz J, Dumler J S. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis: a case series from a single medical center in New York State. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:904–908. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-11-199612010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguero-Rosenfeld M E, Kalantarpour F, Baluch M, Horowitz H W, McKenna D F, Raffalli J T, Tze-Chen H, Wu J, Dumler J S, Wormser G P. Serology of culture-confirmed cases of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:635–638. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.2.635-638.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakken J S, Dumler J S. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:554–560. doi: 10.1086/313948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakken J S, Dumler J S, Chen S M, VanEtta L L, Eckman M R, Walker D H. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in the United States: a new species emerging? JAMA. 1994;272:212–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakken J S, Krueth J, Tilden R L, Asanovich K M, Walls J J, Dumler J S. Duration of IFA serologic response in humans infected with the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:368. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bakken J S, Krueth J, Wilson-Nordskog C, Tilden R L, Asanovich K, Dumler J S. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. JAMA. 1996;275:199–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belongia E A, Reed K D, Mitchell P D, Chyou P-H, Mueller-Rizner N, Finkel M F, Schriefer M E. Clinical and epidemiological features of early Lyme disease and human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Wisconsin. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1472–1477. doi: 10.1086/313532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bjoersdorff A, Berglund J, Kristiansen B E, Soderstrom C, Eliasson I. Varying clinical picture and course of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. Twelve Scandinavian cases of the new tick-born zoonosis are presented. Lakartidningen. 1999;96:4200–4204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Case definitions for infectious conditions under public health surveillance. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1997;46(RR-10):46–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Comer J A, Nicholson W L, Olson J G, Childs J E. Serological testing for human granulocytic ehrlichiosis at a national referral center. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:558–564. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.3.558-564.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dumler J S, Bakken J S. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Wisconsin and Minnesota: a frequent infection with the potential for persistence. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:1027–1030. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.4.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horowitz H W, Aguero-Rosenfeld M E, Dumler S J, McKenna D F, Hsieh T C, Wu J, Schwartz I, Wormser G P. Reinfection with the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:461–463. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-6-199809150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horowitz H W, Aguero-Rosenfeld M E, McKenna D F, Holmgren D, Hsieh T C, Varde S A, Dumler S J, Wu J M, Schwartz I, Rikihisa Y, Wormser G P. Clinical and laboratory spectrum of culture-proven human granulocytic ehrlichiosis: comparison with culture-negative cases. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:1314–1317. doi: 10.1086/515000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ijdo J W, Meek J I, Cartter M L, Magnarelli L A, Wu C, Tenuta S W, Fikrig E, Ryder R W. The emergence of another tickborne infection in the 12-town area around Lyme, Connecticut: human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1388–1393. doi: 10.1086/315389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laferl H, Hogrefe W, Kock T, Pichler H. A further case of acute human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Slovenia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;18:385–386. doi: 10.1007/pl00015026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lotric-Furlan S, Petrovec M, Avsic-Zupanc T, Nicholson W L, Sumner J W, Childs J E, Strle F. Human ehrlichiosis in Central Europe. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1998;24:894–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lotric-Furlan S, Petrovec M, Avsic-Zupanc T, Nicholson W L, Sumner J W, Childs J E, Strle F. Human ehrlichiosis in Europe: clinical and laboratory findings for four patients from Slovenia. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:424–428. doi: 10.1086/514683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicholson W L, Comer J A, Sumner J W, Gingrich-Baker C, Coughlin R T, Magnarelli L A, Olson J G, Childs J E. An indirect immunofluorescence assay using a cell culture-derived antigen for detection of antibodies to the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1510–1516. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1510-1516.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oteo J A, Blanco J R, de Artola V M, Ibarra V. First report of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis from southern Europe (Spain) Emerg Infect Dis. 2000;6:430–431. doi: 10.3201/eid0604.000425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petrovec M, Lotric-Furlan S, Avsic-Zupanc T, Strle F, Brouqui P, Roux V, Dumler J S. Human disease in Europe caused by a granulocytic Ehrlichia species. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1556–1559. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1556-1559.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petrovec M, Sumner J W, Nicholson W L, Childs J E, Strle F, Barlič J, Lotric-Furlan S, Avsic-Zupanc T. Identity of ehrlichial DNA sequences derived from Ixodes ricinus ticks with those obtained from patients with human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Slovenia. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;3:573–574. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.1.209-210.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Dobbenburgh A, van Dam A P, Fikrig E. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in Western Europe. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1214–1216. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904153401517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wallace B J, Brady G, Ackman D M, Wong S J, Jacquette G, Lloyd F, Birkhead G S. Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in New York. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:769–773. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.7.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber R, Pusterla N, Loy M, Lutz H. Fever, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia in a patient with acute Lyme borreliosis were due to human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) agent. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:253–254. doi: 10.1086/517052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woldehiwet Z. Tick-borne fever: a review. Vet Res Commun. 1983;6:163–175. doi: 10.1007/BF02214910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]