Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Emerging evidence suggests that elevated circulating levels of HDL-C (high-density lipoprotein cholesterol) could be linked to an increased mortality risk. However, to the best of our knowledge, the relationship between HDL-C and specific cardiovascular events has never been investigated in patients with hypertension.

METHODS:

To fill this knowledge gap, we analyzed the relationship between HDL-C levels and cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients within the Campania Salute Network in Southern Italy.

RESULTS:

We studied 11 987 patients with hypertension, who were followed for 25 534 person-years. Our population was divided in 3 groups according to the HDL-C plasma levels: HDL-C<40 mg/dL (low HDL-C); HDL-C between 40 and 80 mg/dL (medium HDL-C); and HDL-C>80 mg/dL (high HDL-C). At the follow-up analysis, adjusting for potential confounders, we observed a total of 245 cardiovascular events with a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular events in the low HDL-C group and in the high HDL-C arm compared with the medium HDL-C group. The spline analysis revealed a nonlinear U-shaped association between HDL-C levels and cardiovascular outcomes. Interestingly, the increased cardiovascular risk associated with high HDL-C was not confirmed in female patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Our data demonstrate that there is a U-shaped association between HDL-C and the risk of cardiovascular events in male patients with hypertension.

Keywords: cholesterol, dyslipidemias, heart disease risk factors, hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitors, hypercholesterolemia, population, sex characteristics

HDL-C (High-density lipoprotein cholesterol) has been considered for many years to be inversely associated with cardiovascular risk, a postulate mainly based on seminal epidemiological studies indicating that each 1 mg/dL increase in HDL-C is accompanied by a ~2% to 3% reduction in the risk of cardiovascular death.1-6 However, newer epidemiological and genetic investigations have suggested that HDL-C level might not be predictive of cardiovascular outcomes in all subjects.7-9 More recently, studies performed in populations free of cardiovascular disease10,11 have proposed that very high HDL-C levels can be associated with an increased mortality risk. Nevertheless, the exact relationship between HDL-C levels and specific cardiovascular events remains unknown, especially in a high-risk population like patients with hypertension.

To further clarify this issue, we have analyzed the relationship between HDL-C levels and cardiovascular events in patients with hypertension of the Campania Salute Network, a large population with a high cardiovascular risk, well characterized from the cardiovascular and metabolic points of view, with a long-term follow-up.12-17

METHODS

Patients

The Campania Salute Network is an open electronic registry, networking community hospital-based hypertension clinics and general practitioners from the Campania region in Southern Italy to the Hypertension Research Center of the Federico II University Hospital in Naples (URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov; Unique identifier: NCT02211365).12-17 Recruited subjects are referred to the Hypertension Research Center for cardiovascular imaging and refinement of diagnosis and treatment. At the time of data extraction, the registry included data from 14 161 patients.

For the present analysis, patients with hypertension were selected on the basis of the following inclusion criteria: age ≥18 years; confirmed diagnosis of hypertension; at least one follow-up visit. We excluded patients with history of prevalent coronary/cerebrovascular disease, atrial fibrillation, and valvular heart disease; we also excluded subjects showing conditions that could reduce life expectancy such as cancer, dementia, peripheral vascular disease, abdominal aortic aneurysm, and venous thrombosis (deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism). Follow-up time was defined as the time from enrollment until incident cardiovascular event or cardiovascular death, loss to follow-up, or end of follow-up, whichever came first.

Cardiovascular events were defined as composite of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), sudden cardiac death, fatal and nonfatal myocardial infarction or stroke, myocardial revascularization, heart failure requiring hospitalization, carotid stenting, transient ischemic attack, de novo angina, and atrial fibrillation, as previously described.15

The Federico II University Hospital Ethic Committee approved the database generation of the Campania Salute Network Registry. All participants signed an informed consent allowing the use of their data for scientific purposes.

Cardiovascular Risk Factor and Disease Assessment

Information on demographics and relevant risk factors was obtained at enrollment, including age, sex, race, history of myocardial infarction of stroke, diabetes, and smoking habit. Body weight and height were measured and body mass index was calculated.

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP) were measured after 5 minutes resting in the sitting position, 3 times at 1-minute intervals, according to current guidelines.18 Auscultatory or oscillometric semiautomatic sphygmomanometers attended by trained physicians were used and validated periodically as per standardized protocols,19 using cuffs of appropriate size.16,19 The average of the 2 last measurements was taken as the office BP. After proper training, patients were also invited to measure their BP at home using validated devices and according to current guidelines.18

Follow-up BP was considered optimally controlled when the average office BP values during follow-up visits were <140/90 mm Hg; follow-up home BP was considered optimally controlled when the average home BP self-reported value was <135/85 mm Hg.18,20 Isolated systolic hypertension was defined as systolic BP >140 mm Hg and diastolic BP <90 mm Hg. Obesity was defined as a body mass index ≥30 kg/m2. Fasting glucose and lipid profile were assessed by standard methods; diabetes was defined as history of diabetes, use of any antidiabetic medication, or presence of a fasting blood glucose ≥126 mg/dL, confirmed on 2 different occasions.21,22 Estimation of creatinine clearance (estimated glomerular filtration rate) was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation.23

Ultrasound Analyses

Echocardiograms were performed using commercially available phased-array machines following standardized protocols.16,17 Left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy was defined by prognostically validated sex-specific cutoff values for LV mass/height: >47 g/m2.7 in women and >50 g/m2.7 in men. LV end-diastolic dimension was ratiometrically normalized by height. Relative wall thickness was calculated as the ratio between posterior wall thickness and LV internal radius at the end of the diastolic phase and considered increased if ≥0.43.16,24

Carotid ultrasonography was performed using an ultrasound scanner equipped with a 7.5-MHz high-resolution transducer, following a previously published protocol.16 The maximal carotid intima-media thickness was measured in up to 12 arterial walls, including the right and the left, near and far distal common carotid (1 cm), bifurcation and proximal internal carotid artery.16,17,25

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean±SD for continuous variables and as percentages for categorical variables. ANOVA and χ2 distribution were used for exploratory statistics. Our study population was stratified into 3 groups based on HDL-C levels in mg/dL (<40, 40–80, and >80) to allow the examination of the relationship between HDL-C levels and incidence of cardiovascular events. The HDL-C strata 40 to 80 mg/dL were used as reference ranges for comparison. To account for therapy, single classes of antihypertensive medications, including renin-angiotensin system blockers (ie, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor type 1 antagonists), angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, β-blockers, diuretics, and statins, were considered in the analysis according to their overall use during the individual follow-up, based on the frequency of prescriptions during the control visits. All medications prescribed for >50% of control visits in an individual patient during follow-up were considered as covariates in the multi-variable analyses. A logistic regression analysis was used to assess the effects of HDL-C on cardiovascular events during follow-up, adjusting for age, sex, diabetes, estimated glomerular filtration rate, carotid intima-media thickness, presence of LV hypertrophy, baseline BP values, and therapy (classes of antihypertensive drugs and statins at baseline); these factors have been previously shown to be critical in the determination of cardiovascular risk.26-29 A spline analysis was performed to assess the association between HDL-C levels and the risk of cardiovascular events. A 2-tailed P0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS 23 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) and R Statistical Software (version 4.1.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Data Availability Statement

Reasonable requests to access the data used in these analyses can be made to the first Authors.

RESULTS

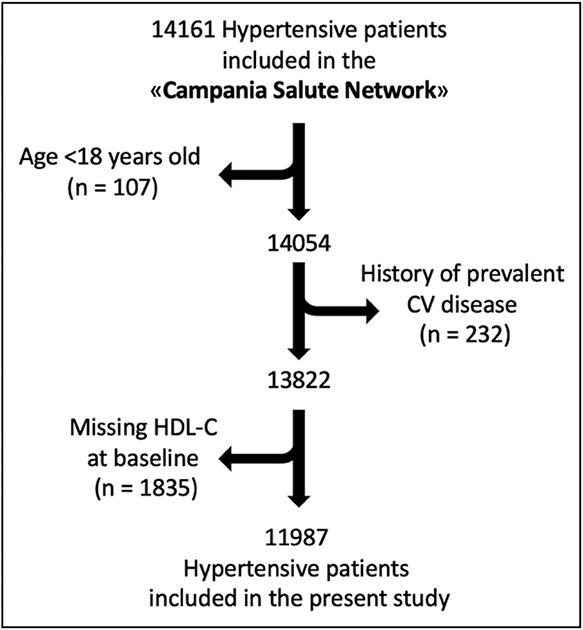

We studied a population of 11 987 patients with hypertension, which were monitored for 25 534 person-years (Figure 1). The mean follow-up was 25.1±31.2 months.

Figure 1. Flow chart of the study.

CV indicates cardiovascular; and HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Our population was divided in 3 groups (Table 1) according to the HDL-C plasma levels: specifically, the first group, with HDL-C below 40 mg/dL (low HDL-C), included 2674 patients; the patients of the second group (medium HDL-C; n=9060) had HDL-C plasma levels between 40 and ≤80 mg/dL; 253 patients with HDL-C>80 mg/dL constituted the third group (high HDL-C).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Our Population

| Parameter | Low HDL cholesterol, n=2674 |

Medium HDL cholesterol, n=9060 |

High HDL cholesterol, n=53 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 50.71 (12.88) | 52.77 (12.78) | 55.80 (12.13) | <0.0001 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 716 (26.2) | 4551 (49.3) | 197 (76.4) | <0.0001 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 142.43 (18.83) | 142.72 (19.26) | 142.65 (19.17) | 0.788 |

| DBP, mm Hg | 89.28 (11.23) | 88.44 (11.37) | 86.74 (12.12) | <0.0001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.99 (4.39) | 27.69 (4.43) | 25.99 (4.20) | <0.0001 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 75.48 (12.34) | 74.82 (11.67) | 74.96 (13.18) | 0.050 |

| HDL-cholesterol, mg/dL | 34.49 (5.17) | 54.11 (9.31) | 88.82 (8.18) | <0.0001 |

| LDL-cholesterol, mg/dL | 127.03 (37.09) | 127.73 (36.47) | 115.17 (39.37) | <0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 197.86 (40.06) | 207.51 (39.69) | 221.15 (40.87) | <0.0001 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 169.56 (90.82) | 126.33 (71.44) | 89.73 (53.84) | <0.0001 |

| Current smokers, n (%) | 563 (20.6) | 1642 (17.8) | 55 (21.3) | 0.002 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 100.97 (25.63) | 97.82 (22.09) | 93.43 (15.57) | <0.0001 |

| Uric acid, mg/dL | 5.64 (2.47) | 5.09 (1.47) | 4.42 (1.30) | <0.0001 |

| AST, IU/L | 24.09±14.03 | 22.88±12.01 | 23.91±19.53 | <0.01 |

| ALT, IU/L | 31.54±21.22 | 26.84±22.74 | 25.08±23.06 | <0.0001 |

| Homocysteine, μmol/L | 16.32±8.28 | 14.48±7.39 | 13.89±8.08 | 0.14 |

| Epinephrine, pg/mL | 81.93 (17.22) | 80.96 (16.89) | 80.37 (16.03) | 0.055 |

| Controlled BP during follow-up, n (%) | 1192 (47.6) | 4106 (48.5) | 119 (48.2) | 0.701 |

| LV mass, g/m2.7 | 47.52 (9.92) | 46.65 (9.58) | 44.96 (9.46) | <0.0001 |

| IMT, mm | 1.67 (0.76) | 1.62 (0.74) | 1.60 (0.78) | 0.095 |

Values are mean±SD or number and percentage. The P value indicates P for trend. ALT indicates alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; BMI, body mass index; BP blood pressure; bpm, beats per minute; CV, cardiovascular; DBP diastolic blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; IMT, intima-media thickness; IU, international units; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; LV, left ventricle; and SBP systolic blood pressure.

The main demographic and clinical characteristics of these 3 groups are depicted in Table 1. Of note, the mean HDL-C plasma concentration in women was significantly higher than in men (54.4±13.3 versus 47.28±11.9 mg/dL; P<0.0001); specifically, in the low HDL-C group, we found a higher percentage of men, while in the high HDL-C group the percentage of female was 3 times greater (Table 1). Importantly, no significant difference among our groups was found in terms of medications (Table 2).

Table 2.

Distribution of Medications in Our Population

| Parameter | Low HDL cholesterol |

Medium HDL cholesterol |

High HDL cholesterol |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of medications in at least 50% of visits, mean, SD | 1.39±1.13 | 1.36±1.12 | 1.35±1.09 | 0.534 |

| ACE inhibitor or ARNI, n (%) | 1714 (65.2) | 5624 (63) | 167 (66.8) | 0.060 |

| Statins, n (%) | 267 (11.1) | 982 (11.9) | 38 (16.4) | 0.056 |

| β-Blockers, n (%) | 580 (22.1) | 2025 (22.7) | 59 (23.60) | 0.750 |

| Calcium channel blockers, n (%) | 617 (23.5) | 1913 (21.40) | 53 (21.2) | 0.077 |

| Antiplatelets, n (%) | 327 (13.5) | 1053 (12.7) | 34 (14.2) | 0.476 |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 901 (34.3) | 3126 (35.0) | 89 (35.6) | 0.773 |

ACE indicates angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARNI, angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors; and HDL, high-density lipoprotein.

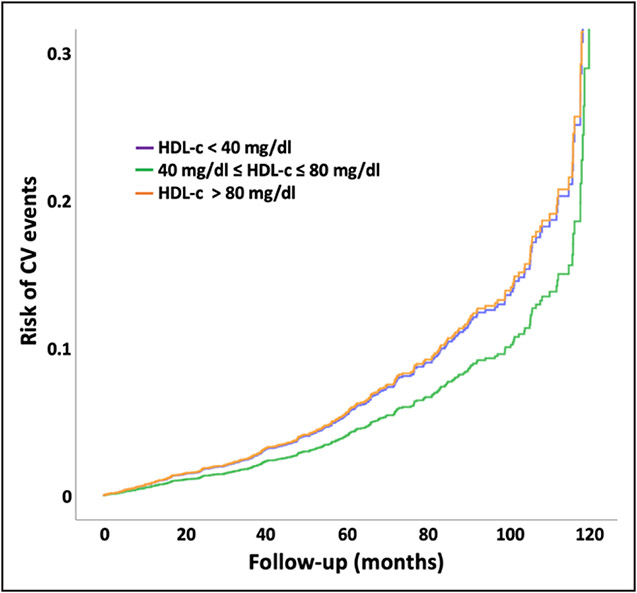

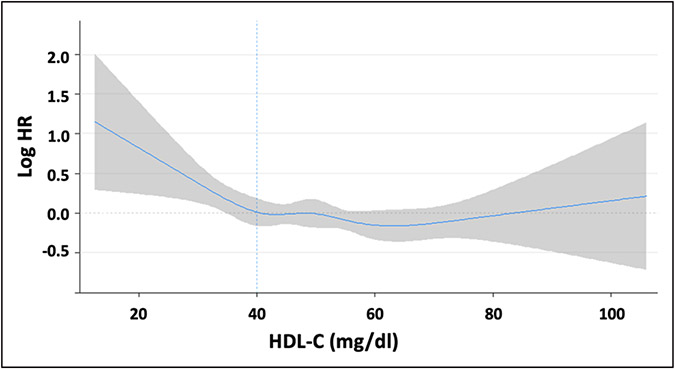

After having adjusted for potential confounders, the follow-up analysis indicated that (Figure 2) there were a total of 245 cardiovascular events with a hazard ratio of 3.5% in the group with HDL-C levels >80 mg/dL, 3.4% in the low HDL-C group (P0.08), and 2.6% in the medium HDL-C group (P=0.02 versus low and high HDL-C groups). We then plotted the spline curves of the Cox regression models to estimate the relative hazard ratio in our population, evidencing a nonlinear U-shaped association between HDL-C levels and cardiovascular outcomes (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Cardiovascular risk is increased by both low HDL-C (high-density lipoprotein cholesterol) and high HDL-C.

Risk of cardiovascular (CV) events in our population divided in 3 groups according to the HDL-C levels.

Figure 3. A U-shaped association links HDL-C (high-density lipoprotein cholesterol) and the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with hypertension.

Spline plot showing the U-shaped association between HDL-C and risk of cardiovascular events. The shaded area represents the 95% CI. The blue dashed line indicates the HDL-C reference value at 40 mg/dL. HR indicates hazard ratio.

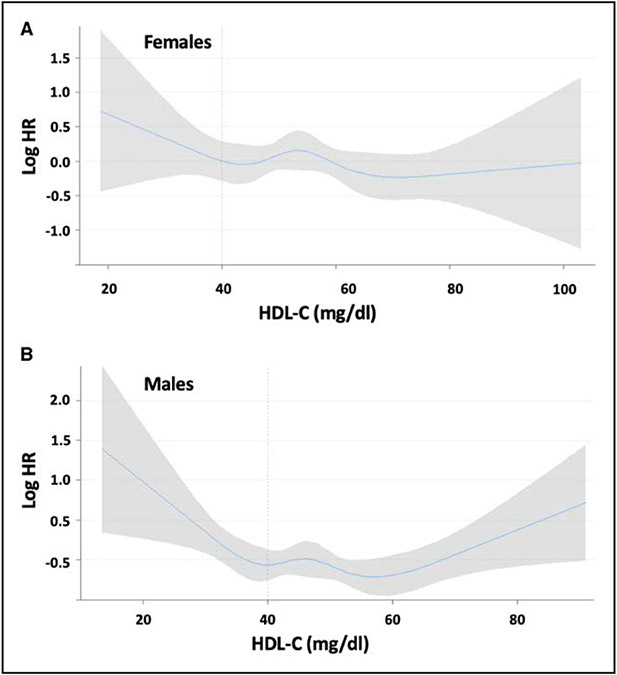

Intriguingly, when subdividing our population in females and males, the increased risk of cardiovascular events associated with elevated HDL-C levels was confirmed in males but not in females (Figure S1A and S1B), a finding corroborated by the relative spline analysis (Figure 4A and 4B).

Figure 4. Female patients with hypertension do not exhibit a U-shaped association between HDL-C (high-density lipoprotein cholesterol) and the risk of cardiovascular events.

Spline plots showing the association between HDL-C and risk of cardiovascular events in female (A) and male (B) patients with hypertension. The shaded area represents the 95% CI. The blue dashed line indicates the HDL-C reference value at 40 mg/dL. HR indicates hazard ratio.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that in patients with hypertension the association between HDL-C and risk of cardiovascular events is U-shaped, with both low and high concentration groups showing a significantly higher prevalence of cardiovascular events compared with the-group of patients with HDL-C between 40 and 80 mg/dL.

The association between high HDL-C and mortality has been explored in a number of observational studies,30-37 which have reported an increased risk of all-cause mortality in subjects with high HDL-C levels. However, the pathogenetic mechanisms underlying this association are still to be defined. According to Hamer et al38 the increased hazard ratio for all-cause mortality observed in subjects with HDL-C >90 mg/dL does not seem to be explained by an augmented cardiovascular mortality, while Hirata et al39 reported a significantly higher risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular mortality in Japanese individuals with extremely high HDL-C levels. In another study, conducted in elderly individuals, a hazard ratio for all-cause mortality for HDL-C >90 mg/dL was found to be driven by both cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality.32 Exploiting data from the Kailuan study,40 both low and high cumulatively averaged HDL-C levels were found to be associated with an increased risk of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke.41 More recently, Liu et al42 analyzed a population of individuals with coronary heart disease showing that those with low (<30 mg/dL) or very high (>80 mg/dL) HDL-C levels have a higher risk of all-cause and cardiovascular death, independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors and alcohol use compared with those with normal HDL-C levels (40–80 mg/dL).

To further investigate the relationship between HDL-C and cardiovascular risk in primary prevention, in this study, we assessed the association between HDL-C and cardiovascular events in a population of hypertensive patients without coronary artery disease. Thus, our observations address an important knowledge gap in the field. Indeed, in the current algorithms used to calculate cardiovascular risk in the general population, HDL-C level is considered as a protective factor, whereas at very high levels, this protective effect does not appear to hold true and, in fact, may confer an increased risk. There are some points to consider before this assumption may be accepted. It is important to note that the exact cutoff used to define high concentrations of cholesterol varies across the different studies, likely on the account of both differences in the studied populations but also in the specific assays used to measure HDL-C. To allow the generalization of our results to different populations we divided our patient in low, medium, and high HDL-C according to previous observations made by Madsen et al,10 who reported that the concentration of HDL-C associated with the lower all case mortality was 54 to 77 mg/dL in men and 69 to 97 mg/dL in women, and the classification used by Liu et al,42 who divided their population in 5 categories with a sex distribution comparable to that of our population and observed that the prevalence of cardiovascular death was lower in the groups 40 to 60 mg/dL and 60 to 80 mg/dL of HDL-C. It is noteworthy that after having divided our population in 3 groups according to the HDL-C levels, the gender was no longer a determinant of the relationship between HDL-C and the risk of cardiovascular events.

After adjusting for potential confounders, we detected a significant difference in the prevalence of cardiovascular events among the 3 groups of hypertensive subjects divided according to their HDL-C levels. This finding could hint the presence of a V-shaped rather than U-shaped association. However, as previously pointed out by other investigators,43 it is important to acknowledge that the nadir is rather broad and encompasses a large portion of the population. Changes in HDL-C levels within this broad nadir do not seem to lead to any relevant change in risk. Keeping in mind the differences in assays used and the populations studied, the inflection point for higher risk with higher HDL-C seems to occur at a range of HDL-C levels >80 mg/dL, thereby suggesting a U more than a V-shaped curve.

A previous investigation conducted in 2 populations10 did not detect a U-shaped association curve between HDL-C levels and prevalence of ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, or ischemic stroke; specifically, a high risk was observed for low concentrations of HDL-C, then there was a plateau around 58 and 77 mg/dL HDL-C for men and women, respectively, with no further decrease in risk with concentrations of HDL-C higher than these values.10 The discrepancy between these data and ours may be explained by the different global cardiovascular risk of the study populations: general population versus subjects with arterial hypertension, or by the inclusion in the cardiovascular events also of heart failure requiring hospitalization, incident coronary revascularization, angina, and atrial fibrillation at the time of their first presentation, which represent earlier evidence of atherosclerotic disease. Whatever the case, the observation of a U-shaped association between HDL-C levels and prevalence of cardiovascular events holds up the conclusion that atherosclerotic disease contributes to the increased mortality risk associated with high levels of HDL-C.

The increased cardiovascular risk associated with elevated levels of HDL-C was not confirmed in female subjects. Notably, we need to consider the low proportion of events (especially in the female cohort), leading to less precise estimates compared with the overall cohort, and this aspect is especially evident when looking at the larger margins of the 95% CIs obtained when plotting the spline curves of the Cox regression models to estimate the relative hazard ratio. These findings are in line with previously demonstrated sex-based differences in terms of cholesterol: for instance, women are known to have higher HDL-C levels than men,44,45 estrogens are known to increase HDL-C,46,47 and elevated total cholesterol has been found to be associated with cardiovascular mortality in older men but may not be an actual risk factor in older women.48

Our observational study does not clarify whether the association between high HDL-C levels and increased cardiovascular risk is causal, since mendelian randomization studies have not supported the causal role for HDL-C in cardiovascular events.9,49 Thus, we can only speculate on the possible pathogenetic mechanisms. The observed association could be an epiphenomenon driven by a pathophysiologic abnormality, perhaps immunologic, genetic, and epigenetic, which increases cardiovascular risk in ways we do not fully understand yet and also increases HDL, substantiating the complexity of HDL-C pathobiology.50-54 Conformation and functional properties of HDL particles55,56 may also be altered in individuals with extreme high HDL-C and an alternative hypothesis could be that in individuals with particularly high HDL-C levels, the functionality of HDL may be compromised such that HDL does not function properly but rather becomes detrimental.

One limitation of our study is the relatively small number of individuals in the highest end of the HDL-C concentration spectrum; nevertheless, the number of hypertensive subjects included in our high HDL-C group did not prevent the possibility to demonstrate a significant increase in the cardiovascular risk after adjustment for confounders. A second limitation is the lack of information on alcohol intake, which has been associated with higher HDL-C levels.57,58 Since we conducted our study in Southern Italy, most of the participants were White patients; hence, our results cannot be generalized to other populations. Finally, we did not determine in all patients cholesterol efflux capacity,59 nor the HDL apolipoproteome, which has been recently associated to cardiovascular mortality in patients with coronary artery disease.60

The major strength of our study is the availability of a prospectively recruited large population with an extremely detailed information on the individual clinical conditions derived by medical records review.

PERSPECTIVES

Taken together, our data indicate that levels of HDL-C >80 mg/dL increase cardiovascular risk in male patients with hypertension. Therefore, we recommend to opportunely revise the algorithms currently used for the calculation of cardiovascular risk; based on the results of the present study, physicians should manage dyslipidemia in hypertensive patients cum grano salis.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND RELEVANCE.

What Is New?

For many years, HDL-C (high-density lipoprotein cholesterol) has been considered to be inversely associated with cardiovascular risk.

Recent reports have suggested that HDL-C level may not be predictive of cardiovascular outcomes in all subjects and that high HDL-C levels could be associated with an increased mortality risk.

We analyzed the relationship between HDL-C levels and cardiovascular events in 11 987 patients with hypertension of the Italian Campania Salute Network, followed-up for 25 534 person-years.

What Is Relevant?

In patients with hypertension, the association between HDL-C and risk of cardiovascular events is U-shaped, with both low and high concentration groups showing a significantly higher prevalence of cardiovascular events. The nonlinear U-shaped association between HDL-C levels and cardiovascular outcomes was confirmed by spline analysis.

The association between high HDL-C and risk of cardiovascular events was not significant in female patients with hypertension.

Clinical/Pathophysiological Implications?

In the algorithms currently used to calculate cardiovascular risk in the general population, HDL-C levels are considered protective. Our findings indicate that at high levels (ie, >80 mg/dL), this protective effect does not appear to hold true and, in fact, may confer an increased risk in male patients with hypertension.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr X. Wang for critical discussion. Dr M. Lembo participates in the PhD program in Cardiovascular Pathophysiology and Therapeutics (CardioPaTh).

Sources of Founding

The Santulli’s Lab is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH): National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI: R01-HL159062, R01HL164772, R01-HL146691, and T32-HL144456), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK: R01-DK123259 and R01-DK033823) to G. Santulli, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS: UL1TR002556-06) to G. Santulli, by the Diabetes Action Research and Education Foundation (to G. Santulli), and by the Monique Weill-Caulier and Irma T. Hirschl Trusts (to G. Santulli). This study was also supported by Grant 00014Prin_2017 ID43237 to V. Trimarco.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BP

blood pressure

- HDL-C

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LV

left ventricle

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.19912.

Contributor Information

Valentina Trimarco, Department of Neuroscience, Reproductive Sciences and Dentistry, “Federico II” University, Naples, Italy.

Raffaele Izzo, Department of Advanced Biomedical Sciences, “Federico II” University, Naples, Italy.

Carmine Morisco, Department of Advanced Biomedical Sciences, “Federico II” University, Naples, Italy; International Translational Research and Medical Education (ITME) Consortium, Naples, Italy.

Pasquale Mone, Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Wilf Family Cardiovascular Research Institute, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York City, NY.

Maria Virginia Manzi, Department of Advanced Biomedical Sciences, “Federico II” University, Naples, Italy.

Angela Falco, Department of Neuroscience, Reproductive Sciences and Dentistry, “Federico II” University, Naples, Italy.

Daniela Pacella, Department of Public Health, “Federico II” University, Naples, Italy.

Paola Gallo, Department of Advanced Biomedical Sciences, “Federico II” University, Naples, Italy.

Maria Lembo, Department of Advanced Biomedical Sciences, “Federico II” University, Naples, Italy.

Gaetano Santulli, Department of Advanced Biomedical Sciences, “Federico II” University, Naples, Italy; International Translational Research and Medical Education (ITME) Consortium, Naples, Italy; Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Wilf Family Cardiovascular Research Institute, Department of Molecular Pharmacology, Fleischer Institute for Diabetes and Metabolism (FIDAM), Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York City, NY.

Bruno Trimarco, Department of Advanced Biomedical Sciences, “Federico II” University, Naples, Italy; International Translational Research and Medical Education (ITME) Consortium, Naples, Italy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wilson PW, Abbott RD, Castelli WP High density lipoprotein cholesterol and mortality. The Framingham Heart Study. Arteriosclerosis. 1988;8:737–741. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.8.6.737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pekkanen J, Linn S, Heiss G, Suchindran CM, Leon A, Rifkind BM, Tyroler HA. Ten-year mortality from cardiovascular disease in relation to cholesterol level among men with and without preexisting cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1700–1707. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199006143222403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sourlas A, Kosmas CE. Inheritance of high and low HDL: mechanisms and management. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2019;30:307–313. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casula M, Colpani O, Xie S, Catapano AL, Baragetti A. HDL in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: in search of a role. Cells. 2021;10:1869. doi: 10.3390/cells10081869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon DJ, Probstfield JL, Garrison RJ, Neaton JD, Castelli WP, Knoke JD, Jacobs DR Jr, Bangdiwala S, Tyroler HA. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and cardiovascular disease. Four prospective American studies. Circulation. 1989;79:8–15. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.1.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rader DJ, Hovingh GK. HDL and cardiovascular disease. Lancet. 2014;384:618–625. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61217-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silbernagel G, Schöttker B, Appelbaum S, Scharnagl H, Kleber ME, Grammer TB, Ritsch A, Mons U, Holleczek B, Goliasch G, et al. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, coronary artery disease, and cardiovascular mortality. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3563–3571. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angeloni E, Paneni F, Landmesser U, Benedetto U, Melina G, Lüscher TF, Volpe M, Sinatra R, Cosentino F. Lack of protective role of HDL-C in patients with coronary artery disease undergoing elective coronary artery bypass grafting. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3557–3562. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Voight BF, Peloso GM, Orho-Melander M, Frikke-Schmidt R, Barbalic M, Jensen MK, Hindy G, Hólm H, Ding EL, Johnson T, et al. Plasma HDL cholesterol and risk of myocardial infarction: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet. 2012;380:572–580. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60312-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madsen CM, Varbo A, Nordestgaard BG. Extreme high high-density lipoprotein cholesterol is paradoxically associated with high mortality in men and women: two prospective cohort studies. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2478–2486. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ko DT, Alter DA, Guo H, Koh M, Lau G, Austin PC, Booth GL, Hogg W, Jackevicius CA, Lee DS, et al. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and cause-specific mortality in individuals without previous cardiovascular conditions: the CANHEART Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:2073–2083. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.08.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Izzo R, de Simone G, Devereux RB, Giudice R, De Marco M, Cimmino CS, Vasta A, De Luca N, Trimarco B. Initial left-ventricular mass predicts probability of uncontrolled blood pressure in arterial hypertension. J Hypertens. 2011;29:803–808. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328343ce32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casalnuovo G, Gerdts E, de Simone G, Izzo R, De Marco M, Giudice R, Trimarco B, De Luca N. Arterial stiffness is associated with carotid atherosclerosis in hypertensive patients (the Campania Salute Network). Am J Hypertens. 2012;25:739–745. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2012.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ciccarelli M, Finelli R, Rivera N, Santulli G, Izzo R, De Luca N, Rozza F, Ceccarelli M, Pagnotta S, Uliano F, et al. The possible role of chromosome X variability in hypertensive familiarity. J Hum Hypertens. 2017;31:37–42. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2016.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canciello G, Mancusi C, Losi MA, Izzo R, Trimarco B, de Simone G, De Luca N. Aortic root dilatation is associated with incident cardiovascular events in a population of treated hypertensive patients: the campania salute network. Am J Hypertens. 2018;31:1317–1323. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpy113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mancusi C, Manzi MV, de Simone G, Morisco C, Lembo M, Pilato E, Izzo R, Trimarco V, De Luca N, Trimarco B. Carotid atherosclerosis predicts blood pressure control in patients with hypertension: the campania salute network registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e022345. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.022345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manzi MV, Mancusi C, Lembo M, Esposito G, Rao MAE, de Simone G, Morisco C, Trimarco V, Izzo R, Trimarco B. Low mechano-energetic efficiency is associated with future left ventricular systolic dysfunction in hypertensives. ESC Heart Fail. 2022;9:2291–2300. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.13908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, Clement DL, Coca A, de Simone G, Dominiczak A, et al. ; Authors/Task Force Members. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European society of hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European society of cardiology and the European society of hypertension. J Hypertens. 2018;36:1953–2041. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muntner P, Shimbo D, Carey RM, Charleston JB, Gaillard T, Misra S, Myers MG, Ogedegbe G, Schwartz JE, Townsend RR, et al. Measurement of blood pressure in humans: a scientific statement from the american heart association. Hypertension. 2019;73:e35–e66. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mone P, Varzideh F, Jankauskas SS, Pansini A, Lombardi A, Frullone S, Santulli G. SGLT2 inhibition via empagliflozin improves endothelial function and reduces mitochondrial oxidative stress: insights from frail hypertensive and diabetic patients. Hypertension. 2022;79:1633–1643. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.122.19586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mone P, Lombardi A, Gambardella J, Pansini A, Macina G, Morgante M, Frullone S, Santulli G. Empagliflozin improves cognitive impairment in frail older adults with type 2 diabetes and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Diabetes Care. 2022;45:1247–1251. doi: 10.2337/dc21-2434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mone P, Gambardella J, Lombardi A, Pansini A, De Gennaro S, Leo AL, Famiglietti M, Marro A, Morgante M, Frullone S, et al. Correlation of physical and cognitive impairment in diabetic and hypertensive frail older adults. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21:10. doi: 10.1186/s12933-021-01442-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson S, Mone P, Jankauskas SS, Gambardella J, Santulli G. Chronic kidney disease: Definition, updated epidemiology, staging, and mechanisms of increased cardiovascular risk. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2021;23:831–834. doi: 10.1111/jch.14186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gambardella J, Jankauskas SS, D’Ascia SL, Sardu C, Matarese A, Minicucci F, Mone P, Santulli G. Glycation of ryanodine receptor in circulating lymphocytes predicts the response to cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2022;41:438–441. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2021.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lanni F, Santulli G, Izzo R, Rubattu S, Zanda B, Volpe M, Iaccarino G, Trimarco B. The Pl(A1/A2) polymorphism of glycoprotein IIIa and cerebrovascular events in hypertension: increased risk of ischemic stroke in high-risk patients. J Hypertens. 2007;25:551–556. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328013cd67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eikendal AL, Groenewegen KA, Anderson TJ, Britton AR, Engström G, Evans GW, de Graaf J, Grobbee DE, Hedblad B, Holewijn S, et al. ; USE-IMT Project Group. Common carotid intima-media thickness relates to cardiovascular events in adults aged <45 years. Hypertension. 2015;65:707–713. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pewowaruk RJ, Korcarz C, Tedla Y, Burke G, Greenland P, Wu C, Gepner AD. Carotid artery stiffness mechanisms associated with cardiovascular disease events and incident hypertension: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Hypertension. 2022;79:659–666. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.18772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soliman EZ, Byington RP, Bigger JT, Evans G, Okin PM, Goff DC Jr, Chen H. Effect of intensive blood pressure lowering on left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with diabetes mellitus: action to control cardiovascular risk in diabetes blood pressure trial. Hypertension. 2015;66:1123–1129. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collard D, Brouwer TF, Olde Engberink RHG, Zwinderman AH, Vogt L, van den Born BH. Initial estimated glomerular filtration rate decline and long-term renal function during intensive antihypertensive therapy: a post hoc analysis of the SPRINT and ACCORD-BP randomized controlled trials. Hypertension. 2020;75:1205–1212. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.14659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhong GC, Huang SQ, Peng Y Wan L, Wu YQ, Hu TY, Hu JJ, Hao FB. HDL-C is associated with mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease and cancer in a J-shaped dose-response fashion: a pooled analysis of 37 prospective cohort studies. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020;27:1187–1203. doi: 10.1177/2047487320914756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu Y, Li M, Huang X, Zhou W, Wang T, Zhu L, Ding C, Tao Y, Bao H, Cheng X. A U-shaped association between the LDL-cholesterol to HDL-cholesterol ratio and all-cause mortality in elderly hypertensive patients: a prospective cohort study. Lipids Health Dis. 2020;19:238. doi: 10.1186/s12944-020-01413-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li ZH, Lv YB, Zhong WF, Gao X, Byers Kraus V, Zou MC, Zhang XR, Li FR, Yuan JQ, Shi XM, et al. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and all-cause and cause-specific mortality among the elderly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:3370–3378. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-02511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oh IH, Hur JK, Ryoo JH, Jung JY, Park SK, Yang HJ, Choi JM, Jung KW, Won YJ, Oh CM. Very high high-density lipoprotein cholesterol is associated with increased all-cause mortality in South Koreans. Atherosclerosis. 2019;283:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2019.01.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilkins JT, Ning H, Stone NJ, Criqui MH, Zhao L, Greenland P, Lloyd-Jones DM. Coronary heart disease risks associated with high levels of HDL cholesterol. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000519. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bowe B, Xie Y, Xian H, Balasubramanian S, Zayed MA, Al-Aly Z. High density lipoprotein cholesterol and the risk of all-cause mortality among U.S. veterans. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:1784–1793. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00730116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barter P, Genest J. HDL cholesterol and ASCVD risk stratification: a debate. Atherosclerosis. 2019;283:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2019.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soria-Florido MT, Schröder H, Grau M, Fitó M, Lassale C. High density lipoprotein functionality and cardiovascular events and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2020;302:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2020.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamer M, O’Donovan G, Stamatakis E. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and mortality: too much of a good thing? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38:669–672. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.310587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirata A, Sugiyama D, Watanabe M, Tamakoshi A, Iso H, Kotani K, Kiyama M, Yamada M, Ishikawa S, Murakami Y et al. ; Evidence for Cardiovascular Prevention from Observational Cohorts in Japan Research G. Association of extremely high levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol with cardiovascular mortality in a pooled analysis of 9 cohort studies including 43,407 individuals: The EPOCH-JAPAN study. J Clin Lipidol. 2018;12:674–684 e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2018.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jin C, Chen S, Vaidya A, Wu Y, Wu Z, Hu FB, Kris-Etherton P, Wu S, Gao X. Longitudinal change in fasting blood glucose and myocardial infarction risk in a population without diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:1565–1572. doi: 10.2337/dc17-0610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li H, Qian F, Zuo Y, Yuan J, Chen S, Wu S, Wang A. U-shaped relationship of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and incidence of total, ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke: a prospective cohort study. Stroke. 2022;53:1624–1632. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.034393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu C, Dhindsa D, Almuwaqqat Z, Ko YA, Mehta A, Alkhoder AA, Alras Z, Desai SR, Patel KJ, Hooda A, et al. Association between high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and adverse cardiovascular outcomes in high-risk populations. JAMA Cardiol. 2022;7:672–680. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2022.0912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Madsen CM, Varbo A, Nordestgaard BG. Novel insights from human studies on the role of high-density lipoprotein in mortality and noncardiovascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021;41:128–140. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.314050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davis CE, Williams DH, Oganov RG, Tao SC, Rywik SL, Stein Y, Little JA. Sex difference in high density lipoprotein cholesterol in six countries. Am J Epidemiol 1996;143:1100–1106. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kesteloot H, Huang DX, Yang XS, Claes J, Rosseneu M, Geboers J, Joossens JV Serum lipids in the People’s Republic of China. Comparison of Western and Eastern populations. Arteriosclerosis. 1985;5:427–433. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.5.5.427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Masi CM, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Serum 2-methoxyestradiol, an estrogen metabolite, is positively associated with serum HDL-C in a population-based sample. Lipids. 2012;47:35–38. doi: 10.1007/s11745-011-3600-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abbas A, Fadel PJ, Wang Z, Arbique D, Jialal I, Vongpatanasin W. Contrasting effects of oral versus transdermal estrogen on serum amyloid A (SAA) and high-density lipoprotein-SAA in postmenopausal women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2004;24:e164–e167. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000140198.16664.8e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Corti MC, Guralnik JM, Salive ME, Harris T, Field TS, Wallace RB, Berkman LF, Seeman TE, Glynn RJ, Hennekens CH. HDL cholesterol predicts coronary heart disease mortality in older persons. JAMA. 1995;274:539–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holmes MV, Asselbergs FW, Palmer TM, Drenos F, Lanktree MB, Nelson CP, Dale CE, Padmanabhan S, Finan C, Swerdlow DI, et al. ; UCLEB consortium. Mendelian randomization of blood lipids for coronary heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:539–550. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Catapano AL, Pirillo A, Bonacina F, Norata GD. HDL in innate and adaptive immunity. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;103:372–383. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lappegård KT, Kjellmo CA, Hovland A. High-density lipoprotein subfractions: much ado about nothing or clinically important? Biomedicines. 2021;9:836. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9070836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Romo EZ, Zivkovic AM. Glycosylation of HDL-associated proteins and its implications in cardiovascular disease diagnosis, metabolism and function. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:928566. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.928566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Novák J, Olejníčková V, Tkáčová N, Santulli G. Mechanistic role of MicroRNAs in coupling lipid metabolism and atherosclerosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;887:79–100. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-22380-3_5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clément AA, Desgagné V, Légaré C, Guay SP, Boyer M, Hutchins E, Corbin F, Keuren-Jensen KV, Arsenault BJ, Guérin R, et al. HDL-enriched miR-30a-5p is associated with HDL-cholesterol levels and glucose metabolism in healthy men and women. Epigenomics. 2021;13:985–994. doi: 10.2217/epi-2020-0456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lund-Katz S, Phillips MC. High density lipoprotein structure-function and role in reverse cholesterol transport. Subcell Biochem. 2010;51:183–227 doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-8622-8_7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cardner M, Yalcinkaya M, Goetze S, Luca E, Balaz M, Hunjadi M, Hartung J, Shemet A, Kränkel N, Radosavljevic S, et al. Structure-function relationships of HDL in diabetes and coronary heart disease. JCI Insight. 2020;5:131491. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.131491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taylor AE, Lu F, Carslake D, Hu Z, Qian Y, Liu S, Chen J, Shen H, Smith GD. Exploring causal associations of alcohol with cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors in a Chinese population using Mendelian randomization analysis. Sci Rep. 2015; 5:14005. doi: 10.1038/srep14005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Salonen JT. Liver damage and protective effect of high density lipoprotein cholesterol. BMJ. 2003;327:1082–1083. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7423.1082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rohatgi A, Khera A, Berry JD, Givens EG, Ayers CR, Wedin KE, Neeland IJ, Yuhanna IS, Rader DR, de Lemos JA, et al. HDL cholesterol efflux capacity and incident cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2383–2393. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Natarajan P, Collier TS, Jin Z, Lyass A, Li Y, Ibrahim NE, Mukai R, McCarthy CP, Massaro JM, D’Agostino RB Sr, et al. Association of an HDL apolipoproteomic score with coronary atherosclerosis and cardiovascular death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2135–2145. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Reasonable requests to access the data used in these analyses can be made to the first Authors.