Abstract

Background

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic affects common diseases, but its impact on hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) is unclear. Google Trends data is beneficial for approximate real-time statistics and because of ease in access, is expected to be used for infection explanation from an information-seeking behavior perspective. We aimed to explain HFMD cases before and during COVID-19 using Google Trends.

Methods

HFMD cases were obtained from the National Institute of Infectious Diseases, and Google search data from 2009 to 2021 in Japan were downloaded from Google Trends. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated between HFMD cases and the search topic “HFMD” from 2009 to 2021. Japanese tweets containing “HFMD” were retrieved to select search terms for further analysis. Search terms with counts larger than 1000 and belonging to ranges of infection sources, susceptible sites, susceptible populations, symptoms, treatment, preventive measures, and identified diseases were retained. Cross-correlation analyses were conducted to detect lag changes between HFMD cases and search terms before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Multiple linear regressions with backward elimination processing were used to identify the most significant terms for HFMD explanation.

Results

HFMD cases and Google search volume peaked around July in most years, excluding 2020 and 2021. The search topic “HFMD” presented strong correlations with HFMD cases, except in 2020 when the COVID-19 outbreak occurred. In addition, the differences in lags for 73 (72.3%) search terms were negative, which might indicate increasing public awareness of HFMD infections during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results of multiple linear regression demonstrated that significant search terms contained the same meanings but expanded informative search content during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

The significant terms for the explanation of HFMD cases before and during COVID-19 were different. Awareness of HFMD infections in Japan may have improved during the COVID-19 pandemic. Continuous monitoring is important to promote public health and prevent resurgence. The public interest reflected in information-seeking behavior can be helpful for public health surveillance.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12879-022-07790-9.

Keywords: HFMD, Infodemiology, Google Trends, Infection, Explanation

Background

Hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) is an infectious disease that causes blistering rashes on the mouth, hands, and feet. Most infected individuals recover from HFMD within a few days of infection. Various comorbidities, including myocarditis, neurogenic pulmonary edema, acute flaccid paralysis, and central nervous system complications such as meningitis, cerebellar ataxia, and encephalitis, can also occur [1, 2]. HFMD is distributed worldwide, and outbreaks often occur during the summer and early fall in the United States. Large outbreaks in Cambodia, China, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam have been reported over the past 2 decades [3, 4]. HFMD is seasonal in temperate Asia with a summer peak, and subtropical Asia with spring and fall peaks, but not in tropical Asia, indicating that temperate Japan has a climatic role [5]. During the summer of 2011, Japan had the largest HFMD epidemic on record, with 347,362 reported cases [6]. Coxsackievirus A6 (CV-A6) infection is responsible for most cases, with co-circulation of coxsackievirus A16 (CV-A16) and enterovirus A71 (EV-A71) [7]. EV-A71 was sporadically detected from October 2014 onward. It became the predominant serotype in 2018, with approximately 70,000 reported cases, following an increase in its spread from the end of 2017 [8]. Since June 2019, a severe outbreak of HFMD has occurred in multiple regions of Japan, attracting public attention [9]. As enteroviruses can spread rapidly by droplet and fomite transmission among children in daycare centers and kindergartens, understanding HFMD outbreaks is vital to public health, particularly during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic [10].

Rapid recognition and reporting of HFMD infection are essential, and several studies have constructed models for explaining HFMD infection [11–15]. Rui et al. explored epidemiological characteristics and calculated the early warning signals of HFMD using a logistic differential equation (LDE) model in seven regions of China [11]. Yu et al. forecasted the number of HFMD cases with wavelet-based hybrid models in Zhengzhou, China [12]. Zhang et al. proposed a landscape dynamic network marker (L-DNM) to detect pre-outbreak signals of HFMD in Tokyo, Hokkaido, and Osaka, Japan [13]. Gao et al. used monthly HFMD infection cases and meteorological data to construct a weather-based early warning model with a generalized additive model across China [14]. Zhao et al. used a meta-learning framework and combines Baidu search queries for real-time estimation of HFMD cases [15]. The above studies used a range of data, including monthly or weekly HFMD infectious cases [11, 12, 14], dynamic information from city networks, horizontal high-dimensional data, records of clinic visits [13], meteorological data [14], and Baidu search queries data [15] which are relatively difficult to access or delayed updates in Japan. Traditional surveillance and reporting systems lag an outbreak by 1 to 2 weeks because of the reporting and verification process. In Japan, the National Institute of Infectious Disease (NIID) has monitored the outbreak of various infectious diseases and issued weekly reports since 1999, but delayed for several weeks [16]. In addition, no studies have focused on changes in HFMD affected by the COVID-19 pandemic by Internet searching data compared with previous studies. As of August 2022, Google search data was considered reliable because its market share in Japan has been over 70% since 2009 [17, 18]. Google Trends data offers real-time and labor-saving information search by the public, which may be valuable for infection surveillance.

The science of distribution and determinants of information in an electronic medium, specifically the Internet, or in a population, to inform public health and policy is defined as “infodemiology” [19]. Google Trends is frequently used in infodemiology research to gauge public interests [20]. Google Trends reflects public information-seeking behavior and allows users to analyze Google search data for specific search terms in any country or region over a selected period [21, 22]. Studies have shown that online query trends correlate with real-life epidemiologic phenomena such as flu [23], sinusitis [24], lifestyle-related disease [25], asthma [26], and pruritus [27]. Researchers have also investigated public interest and information-seeking behaviors in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [28], cancer [29, 30], bariatric surgery [31], kidney stone surgery [32], and suicide [33]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, similar studies using Google Trends search data were conducted to predict COVID-19 infectious cases [34, 35], explore public attitudes toward vaccination [36–38], identify symptoms caused by pandemics [39–41], and assess affected medical services [42–44]. The above studies indicate that Google Trends can assist in gaining a better understanding and analysis of health information-seeking behavior. Information from Google Trends can be used to supplement current infection reports with lag times.

This study aimed to explain HFMD infections using Google Trends data from Japan before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Data

We obtained actual HFMD cases from the weekly reports issued by NIID, which included new infectious cases and sentinel cases by prefecture and updated them from 1999 to present [16]. Additionally, we set the geographic location to Japan and the category to health to limit irrelevant results and downloaded the relative search volume (RSV) of the “HFMD” search topic using Google Trends from January 1, 2009, to December 31, 2021. The normalized RSV data represent the search interest relative to the highest point for a given region and time. The scales of normalized RSV varied from 0 to 100, where 0 meant there was insufficient data for a term, and 100 was the peak popularity. We selected a search topic instead of the search term “HFMD” for comprehensive search information, and limited the period from 2009 to 2021. In this study, we used the search topic "HFMD" and the search term "HFMD." The weekly RSV of the search topic “HFMD” for each year between 2009 and 2021 were gathered for further analysis.

To identify the significant factors of HFMD infection, we created multiple linear regression models using HFMD-related search terms selected by Japanese tweets. We retrieved Japanese tweets through the publicly available Twitter Stream application programming interface (API) by querying the keywords “HFMD” to select “HFMD” related top words. Google applied improvements to the data collection system on January 1, 2016, and January 1, 2022. For consistency, 275,010 tweets restricted to 2016 and 2021 were downloaded for this study. Tokenization was used to select the top words in Japanese tweets, which is a fundamental step in many natural language processing (NLP) methods, especially for languages such as Japanese that are written without spaces between words. We tokenized all the tweets and analyzed the unigram tokens. Website links, special characters, numbers, and “amp” (ampersands) were removed from the tweets before tokenization. Python packages SpaCy and GiNZA were used to remove Japanese stop words and implement tokenization. White space characters joined tokenized words into the text in the original order. The Python package scikit-learn was used to convert the white space-joined texts into unigram tokens and calculate the token counts. The counts of tokens are provided in Additional file 1. Search terms with counts larger than 1000 and belonging to ranges of infection sources, susceptible sites, susceptible populations, symptoms, treatment, preventive measures, and identified diseases were selected for further analysis. Selected terms with corresponding interpretations and categories are provided in Additional files 2 and 3, respectively. We downloaded the weekly RSV of selected search terms through Google Trends in two periods: before (2016–2019) and during the pandemic (2020–2021) based on the first case of COVID-19 in Japan on January 16, 2020.

Statistical analysis

First, we calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient between the HFMD cases and RSV of the search topic “HFMD” each year from 2009 to 2021 instead of the whole period due to the periodic characteristics. Because our response variable HFMD cases and explanatory variables search topic RSV were measured on a continuous scale, the parametric test was selected instead of non-parametric analysis [45].

Second, we conducted cross-correlation analyses between the HFMD cases and RSV of the selected search terms. Cross-correlation is a measure of the similarity between two series as a function of the displacement of one relative to the other, and is used to objectively estimate the time lag between cases of HFMD infection and related search terms [46]. We set the maximum lag to ± 20 weeks because of the periodic characteristics of the HFMD infection. We obtained 40 cross-correlation coefficients for each HFMD-related search term, before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Next, we selected the coefficients with the greatest absolute values and exhibited their true values. Finally, we compared the coefficients with the highest absolute values in the periods before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Regarding these coefficients, we assumed negative, zero, or positive values, with the greatest absolute value representing the search terms that occurred earlier, coincided with, or later than the actual HFMD cases. Differences in lags during and before the COVID-19 pandemic were calculated to determine public awareness of HFMD.

Third, we conducted multiple linear regressions to identify the most important Google search terms to explain HFMD infection before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. We included HFMD-related search terms for multiple linear regression explanatory variables with actual HFMD cases as response variables. Collinearity is the correlation between explanatory variables that express a linear relationship in a regression model. When explanatory variables are correlated in the same regression model, they cannot explain the response in a dependent manner. We normalized the RSV of each selected term to avoid collinearity in the regression models. Several common methods have been used for explanatory variable selection to identify the most significant search terms and limit the number of explanatory variables, including forward selection, backward elimination, and stepwise regression [47]. Backward elimination was used in this study to find the best subset of search terms owing to its easy implementation and automated availability. We used a p-value threshold of 0.05 to remove unnecessary search terms. In each round, we removed the search term with the highest p-value and reconstructed a multiple linear regression model until all the p-values were below the threshold.

To assess the performance of the linear regression model, the coefficients of determination R2 or adjusted R2, which indicate how much variation in response is explained by the model, are often used [48]. We selected the adjusted R2 value for model evaluation to avoid overfitting the model.

Results

Basic description of HFMD cases and “HFMD” RSV

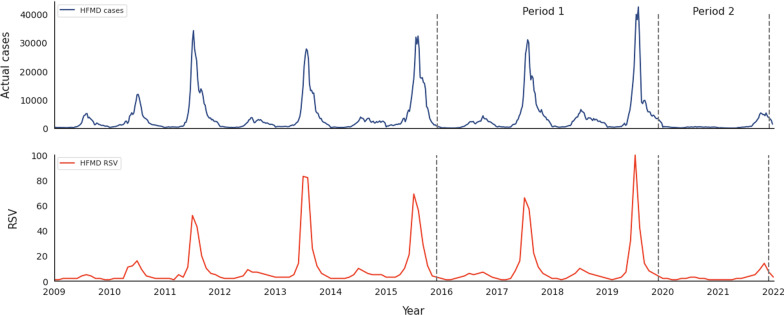

Figure 1 presents the actual HFMD and RSV cases from 2009 to 2021. Visual inspection of the figure indicates that both the actual HFMD cases and RSV of Google Trends peaked around July in most years, except for 2020 and 2021. The number of HFMD infections surged after 2011, peaking every 2 years before 2020. RSV levels coincided with this trend. In 2020, no periodic peak in infection was observed, whereas in 2021, the peak was delayed to November.

Fig. 1.

Monthly number of cases and RSV of HFMD from 2009 to 2021

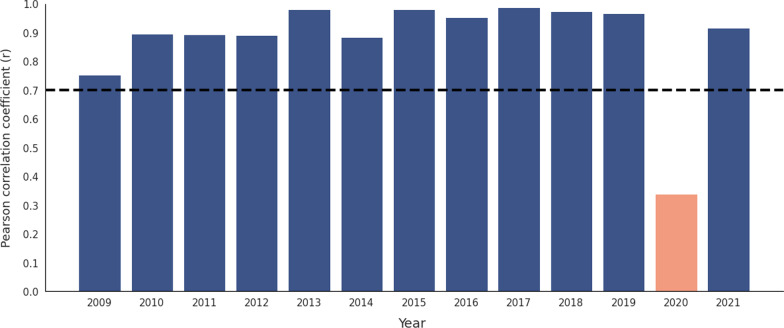

As shown in Fig. 2, we calculated the correlation between the actual HFMD cases and RSV for each year from 2009 to 2021. The mean (standard error) was 0.820 (0.052). Most coefficient values were greater than 0.7, except 0.338 in 2020. The Pearson correlation coefficients are provided in Additional file 4: Table S1.

Fig. 2.

Correlation between the number of cases and RSV of HFMD for each year from 2009 to 2021

Cross-correlation between HFMD cases and search term RSV before and during the pandemic

We performed cross-correlation analyses to determine the temporal relationship between HFMD cases and the search term RSV. Cross-correlation results before and during the pandemic are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cross-correlation analysis of HFMD cases and search terms RSV

| Search terms (English) | Search terms (Japanese) | Period 1 (2015–2019) | Period 2 (2020–2021) | Lag changes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lags (week) | Coefficients (r) | Lags (week) | Coefficients (r) | |||

| / | / | Earlier | ||||

| Hodgkin | ホジキン | 19 | 0.017 | − 19 | 0.08 | − 38 |

| Lymphoma | リンパ腫 | 19 | 0.196 | − 19 | 0.056 | − 38 |

| Visits | 受診 | 19 | 0.202 | − 15 | 0.167 | − 34 |

| Vaccine | ワクチン | 17 | 0.662 | − 13 | 0.908 | − 30 |

| Fever | 発熱 | 19 | 0.096 | − 11 | 0.886 | − 30 |

| Antipyretic drug | 解熱剤 | 19 | 0.177 | − 11 | 0.926 | − 30 |

| Chickenpox | 水痘 | 19 | 0.177 | − 11 | 0.498 | − 30 |

| Reduce fever | 解熱 | 19 | 0.233 | − 10 | 0.816 | − 29 |

| Examination | 検査 | 19 | 0.199 | − 10 | 0.573 | − 29 |

| Low grade fever | 微熱 | 19 | 0.07 | − 9 | 0.178 | − 28 |

| Pediatric | 小児科 | 17 | 0.529 | − 6 | 0.639 | − 23 |

| Child (hiragana) | こども | 15 | 0.462 | − 6 | 0.67 | − 21 |

| Intense pain | 激痛 | 2 | 0.093 | − 19 | 0.067 | − 21 |

| Department of dermatology | 皮膚科 | 1 | 0.422 | − 16 | 0.486 | − 17 |

| Itch (word morphing) | 痒く | 0 | 0.554 | − 16 | 0.52 | − 16 |

| Influenza | インフルエンザ | 19 | 0.383 | 3 | 0.203 | − 16 |

| Rest | 休み | 2 | 0.428 | − 14 | 0.363 | − 16 |

| Rash (word morphing) | プツプツ | − 2 | 0.478 | − 17 | 0.325 | − 15 |

| Swimming pool | プール | 0 | 0.625 | − 15 | 0.699 | − 15 |

| Entero- | エンテロ | − 3 | 0.153 | − 17 | 0.319 | − 14 |

| Adult | 大人 | − 1 | 0.669 | − 15 | 0.642 | − 14 |

| Sole of the foot | 足底 | − 4 | 0.437 | − 18 | 0.334 | − 14 |

| Nasal mucus | 鼻水 | 18 | 0.326 | 4 | 0.13 | − 14 |

| Rash (word morphing) | ぶつぶつ | − 1 | 0.42 | − 14 | 0.329 | − 13 |

| Rash (word morphing) | 発疹 | − 1 | 0.791 | − 14 | 0.448 | − 13 |

| School-aged children | 学童 | − 3 | 0.124 | − 16 | 0.059 | − 13 |

| Pharynx | 咽頭 | − 2 | 0.36 | − 15 | 0.15 | − 13 |

| Septicemia | 敗血症 | 12 | 0.338 | − 1 | 0.109 | − 13 |

| Summer cold | 夏風邪 | 1 | 0.598 | − 12 | 0.587 | − 13 |

| Go to kindergarten | 登園 | − 1 | 0.431 | − 14 | 0.418 | − 14 |

| Adeno- | アデノ | − 7 | 0.559 | − 19 | 0.644 | − 12 |

| adenovirus | アデノウイルス | − 7 | 0.558 | − 19 | 0.663 | − 12 |

| COVID-19 (short name) | コロナ | − 1 | 0.012 | − 13 | 0.187 | − 12 |

| Rash (hiragana) | ボツボツ | − 1 | 0.227 | − 13 | 0.208 | − 12 |

| Erythema | 紅斑 | − 1 | 0.376 | − 13 | 0.427 | − 12 |

| Young child | 小児 | − 7 | 0.296 | − 19 | 0.433 | − 12 |

| Kindergarten | 幼稚園 | − 7 | 0.274 | − 19 | 0.129 | − 12 |

| Influenza (short name) | インフル | 19 | 0.36 | 7 | 0.167 | − 12 |

| Enterovirus | エンテロウイルス | − 5 | 0.012 | − 16 | 0.141 | − 11 |

| Infant | 赤ちゃん | − 7 | 0.21 | − 18 | 0.527 | − 11 |

| High fever | 高熱 | − 1 | 0.147 | − 12 | 0.63 | − 11 |

| Infant (different stages) | 乳幼児 | − 8 | 0.051 | − 19 | 0.109 | − 11 |

| Palm (colloquial term) | 手のひら | − 6 | 0.459 | − 17 | 0.414 | − 11 |

| Sole of the foot (colloquial term) | 足裏 | − 6 | 0.512 | − 17 | 0.497 | − 11 |

| Daycare center | 保育園 | − 5 | 0.361 | − 15 | 0.411 | − 10 |

| Conjunctivitis | 結膜炎 | − 8 | 0.447 | − 18 | 0.139 | − 10 |

| Skin | 皮膚 | − 7 | 0.519 | − 17 | 0.492 | − 10 |

| Exhaustion | 疲れ | − 9 | 0.47 | − 19 | 0.417 | − 10 |

| Toddler | 幼児 | − 7 | 0.069 | − 17 | 0.491 | − 10 |

| Vomiting | 嘔吐 | 19 | 0.218 | 9 | 0.224 | − 10 |

| Gastroenteritis | 胃腸炎 | 19 | 0.159 | 9 | 0.404 | − 10 |

| Urticaria | 蕁麻疹 | − 3 | 0.58 | − 12 | 0.678 | − 9 |

| palm (written term) | 手掌 | − 10 | 0.118 | − 19 | 0.086 | − 9 |

| Swelling | 腫れ | − 3 | 0.513 | − 12 | 0.597 | − 9 |

| Norovirus | ノロ | 19 | 0.11 | 10 | 0.221 | − 9 |

| Cold | 風邪 | 18 | 0.403 | 9 | 0.163 | − 9 |

| Hospital | 病院 | − 7 | 0.239 | − 15 | 0.265 | − 8 |

| Vesicle | 水疱 | − 1 | 0.595 | − 8 | 0.668 | − 7 |

| Itch (word morphing) | 痒み | − 8 | 0.272 | − 15 | 0.138 | − 7 |

| Child (mixed) | 子ども | − 5 | 0.096 | − 12 | 0.629 | − 7 |

| Coxsackie (virus) | コクサッキー | − 2 | 0.216 | − 8 | 0.123 | − 6 |

| Eczema | 湿疹 | − 6 | 0.451 | − 12 | 0.492 | − 6 |

| Diarrhea | 下痢 | − 7 | 0.267 | − 13 | 0.381 | − 6 |

| Chlamydia | クラミジア | 5 | 0.133 | − 1 | 0.226 | − 6 |

| Chickenpox (colloquial term) | 水疱瘡 | − 5 | 0.411 | − 10 | 0.37 | − 5 |

| Herpangina | ヘルパンギーナ | 0 | 0.575 | − 4 | 0.716 | − 4 |

| Measles | 麻疹 | − 8 | 0.077 | − 12 | 0.655 | − 4 |

| Papule | 丘疹 | − 8 | 0.124 | − 12 | 0.237 | − 4 |

| Appetite | 食欲 | − 7 | 0.08 | − 10 | 0.603 | − 3 |

| Diagnosis | 診断 | − 16 | 0.218 | − 19 | 0.276 | − 3 |

| Child (kanji) | 子供 | − 11 | 0.248 | − 14 | 0.489 | − 3 |

| Herpes | ヘルペス | 19 | 0.267 | 17 | 0.094 | − 2 |

| Herpes | 疱疹 | − 1 | 0.385 | − 2 | 0.815 | − 1 |

| / | / | Coincide | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral cavity (synonym) | 口腔 | − 19 | 0.248 | − 19 | 0.189 | 0 |

| Aphtha | アフタ | 9 | 0.143 | 9 | 0.143 | 0 |

| Gargle | うがい | 19 | 0.4 | 19 | 0.005 | 0 |

| Disinfection | 消毒 | 19 | 0.078 | 19 | 0.13 | 0 |

| Company | 会社 | 19 | 0.183 | 19 | 0.059 | 19 |

| / | / | Later | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hand and foot | 手足 | − 1 | 0.976 | 0 | 0.842 | 1 |

| Pneumonia | 肺炎 | 18 | 0.099 | 19 | 0.128 | 1 |

| School | 学校 | 18 | 0.068 | 19 | 0.051 | 19 |

| Pain (word morphing) | 痛い | − 10 | 0.305 | − 8 | 0.738 | 2 |

| Mycoplasma | マイコプラズマ | 17 | − 0.031 | 19 | 0.143 | 2 |

| Stomach | お腹 | − 7 | 0.316 | − 4 | 0.493 | 3 |

| Handwashing | 手洗い | 15 | 0.255 | 19 | 0.133 | 4 |

| Allergy | アレルギー | − 19 | 0.42 | − 13 | 0.412 | 6 |

| Itch(hiragana) | かゆい | − 19 | 0.371 | − 12 | 0.41 | 7 |

| Pain (word morphing) | 痛み | − 19 | 0.203 | − 10 | 0.309 | 9 |

| Pain (word morphing) | 痛く | − 19 | 0.245 | − 8 | 0.313 | 11 |

| Headache | 頭痛 | − 19 | 0.032 | − 8 | 0.535 | 11 |

| Stomatitis | 口内炎 | 0 | 0.52 | 19 | 0.05 | 19 |

| Vesicle (colloquial term) | 水泡 | 0 | 0.678 | 19 | − 0.002 | 19 |

| Meningitis | 髄膜炎 | 0 | 0.304 | 19 | 0.058 | 19 |

| Typhus | チフス | − 4 | 0.084 | 19 | 0.054 | 23 |

| Rubella | 風疹 | − 6 | 0.017 | 19 | 0.086 | 25 |

| Hemolytic streptococcus | 溶連菌 | − 7 | 0.355 | 19 | 0.132 | 26 |

| Infant (different stages) | 乳児 | − 7 | 0.107 | 19 | 0.083 | 26 |

| Legionella | レジオネラ | − 18 | 0.282 | 9 | 0.064 | 27 |

| Virus | ウイルス | − 9 | 0.207 | 19 | 0.125 | 28 |

| Oral cavity (synonym) | 口内 | − 19 | 0.084 | 9 | 0.054 | 28 |

| Specific medicine | 特効薬 | − 19 | 0.129 | 19 | 0.11 | 38 |

Compared with period 1, the temporal correlation between HFMD cases and the search term RSV changed in period 2. In period 1, 61 (60.4%), 6 (5.9%), and 34 (33.7%) of the search terms RSV presented earlier, coincided with, and later than the HFMD cases, respectively. In period 2, 73 (72.3%), 1 (1%), and 27 (26.7%) presented earlier, coincided with, and later, respectively, than the HFMD cases. The differences in lags for 73 (72.3%) search terms were negative, which might indicate increasing public awareness of HFMD infections during the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast, lags for the five search terms did not change, and 23 search terms exhibited delays.

Essential search terms for explaining HFMD cases before and during the pandemic

We identified the most significant search terms for HFMD infection using multiple linear regression with backward elimination. As shown in Table 2, 18 search terms were significant in period 1 and accounted for an adjusted R2 value of 96.7% of the variation in HFMD infection. Conversely, as shown in Table 3, 57 search terms were detected as significant, with adjusted R2 = 98.4%, in period 2, which included more critical variables than in period 1. The model specification formulas are provided in Additional file 4: Table S2 and Table S3.

Table 2.

Multiple linear regression model of HFMD cases and RSV of selected search terms from 2016 to 2019

| Search terms (English) | Search terms (Japanese) | Model summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized β | Std.Error | P-value | ||

| Virus | ウイルス | 0.0507 | 0.019 | 0.007 |

| Herpangina | ヘルパンギーナ | − 0.1034 | 0.033 | 0.002 |

| Diarrhea | 下痢 | − 0.0998 | 0.021 | < 0.001 |

| Oral cavity (synonym) | 口内 | 0.0290 | 0.015 | 0.049 |

| Summer cold | 夏風邪 | 0.1361 | 0.037 | < .001 |

| Adult | 大人 | 0.1306 | 0.032 | < .001 |

| Young child | 小児 | − 0.0372 | 0.017 | 0.032 |

| Pediatric | 小児科 | 0.0641 | 0.019 | 0.001 |

| Hand and foot | 手足 | 0.8575 | 0.026 | < 0.001 |

| Chickenpox (colloquial term) | 水疱瘡 | − 0.0634 | 0.018 | 0.001 |

| Eczema | 湿疹 | 0.0506 | 0.018 | 0.006 |

| Intense pain | 激痛 | 0.0361 | 0.014 | 0.010 |

| Exhaustion | 疲れ | − 0.0474 | 0.021 | 0.024 |

| Itch (word morphing) | 痒く | 0.0468 | 0.019 | 0.014 |

| Swelling | 腫れ | − 0.0481 | 0.022 | 0.033 |

| Reduce fever | 解熱 | − 0.1042 | 0.021 | < 0.001 |

| Sole of the foot | 足底 | − 0.0589 | 0.023 | 0.012 |

| Nasal mucus | 鼻水 | − 0.0743 | 0.023 | 0.001 |

Adjusted R2 = 96.7%

Table 3.

Multiple linear regression of HFMD cases and RSV of selected search terms between 2020 and 2021

| Search terms (English) | Search terms (Japanese) | Model summary | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized β | Std.Error | P-value | ||

| Adenovirus | アデノウイルス | − 0.2816 | 0.04 | < 0.001 |

| Influenza (short name) | インフル | − 0.1938 | 0.062 | 0.003 |

| Entero- | エンテロ | 0.1566 | 0.021 | < 0.001 |

| Stomach | お腹 | 0.0897 | 0.028 | 0.002 |

| Coxsackie (virus) | コクサッキー | 0.0446 | 0.02 | 0.034 |

| Child (hiragana) | こども | − 0.4402 | 0.111 | < 0.001 |

| COVID-19 (short name) | コロナ | 0.6273 | 0.102 | < 0.001 |

| Rash (word morphing) | プツプツ | 0.1868 | 0.029 | < 0.001 |

| Herpangina | ヘルパンギーナ | 0.8604 | 0.044 | < 0.001 |

| Herpes | ヘルペス | − 0.3042 | 0.042 | < 0.001 |

| Hodgkin | ホジキン | 0.0464 | 0.017 | 0.009 |

| Mycoplasma | マイコプラズマ | 0.1905 | 0.069 | 0.008 |

| Legionella | レジオネラ | 0.1888 | 0.025 | < 0.001 |

| Vaccine | ワクチン | − 1.1388 | 0.136 | < 0.001 |

| Diarrhea | 下痢 | 0.2803 | 0.056 | < 0.001 |

| Papule | 丘疹 | 0.0863 | 0.02 | < 0.001 |

| Infant (different stages) | 乳児 | − 0.2984 | 0.034 | < 0.001 |

| Infant (different stages) | 乳幼児 | 0.0712 | 0.024 | 0.005 |

| Daycare center | 保育園 | 0.3336 | 0.049 | < 0.001 |

| Visits | 受診 | 0.1898 | 0.038 | < 0.001 |

| Oral cavity (synonym) | 口腔 | 0.1055 | 0.034 | 0.004 |

| Pharynx | 咽頭 | 0.1182 | 0.022 | < 0.001 |

| Vomiting | 嘔吐 | − 0.0955 | 0.046 | 0.045 |

| Summer cold | 夏風邪 | − 0.9272 | 0.061 | < 0.001 |

| Child (mixed) | 子ども | 0.1727 | 0.045 | < 0.001 |

| Child (kanji) | 子供 | 0.2808 | 0.041 | < 0.001 |

| Young child | 小児 | − 0.2281 | 0.049 | < 0.001 |

| Pediatric | 小児科 | 0.6066 | 0.114 | < 0.001 |

| Toddler | 幼児 | 0.1418 | 0.045 | 0.003 |

| Kindergarten | 幼稚園 | − 0.2225 | 0.043 | < 0.001 |

| Palm (colloquial term) | 手のひら | 0.1388 | 0.029 | < 0.001 |

| Handwashing | 手洗い | − 0.1137 | 0.051 | 0.031 |

| Septicemia | 敗血症 | 0.1228 | 0.017 | < 0.001 |

| Vesicle (colloquial term) | 水泡 | − 0.2038 | 0.037 | < 0.001 |

| Vesicle | 水疱 | 0.1718 | 0.035 | < 0.001 |

| Chickenpox | 水痘 | 0.0902 | 0.021 | < 0.001 |

| Disinfection | 消毒 | − 0.4493 | 0.082 | < 0.001 |

| Hemolytic streptococcus | 溶連菌 | 0.3638 | 0.086 | < 0.001 |

| Specific medicine | 特効薬 | − 0.4039 | 0.047 | < 0.001 |

| Herpes | 疱疹 | 0.1362 | 0.042 | 0.002 |

| Exhaustion | 疲れ | − 0.3952 | 0.041 | < 0.001 |

| Hospital | 病院 | − 0.214 | 0.05 | < 0.001 |

| Itch (word morphing) | 痒み | 0.1993 | 0.032 | < 0.001 |

| Pain (word morphing) | 痛い | − 0.2462 | 0.047 | < 0.001 |

| Pain (word morphing) | 痛く | − 0.2206 | 0.029 | < 0.001 |

| Rash (word morphing) | 発疹 | − 0.2028 | 0.055 | 0.001 |

| Skin | 皮膚 | 0.1754 | 0.04 | < 0.001 |

| Conjunctivitis | 結膜炎 | − 0.1782 | 0.035 | < 0.001 |

| Pneumonia | 肺炎 | 0.3648 | 0.06 | < 0.001 |

| Swelling | 腫れ | 0.152 | 0.043 | 0.001 |

| Urticaria | 蕁麻疹 | 0.747 | 0.147 | < 0.001 |

| Antipyretic drug | 解熱剤 | 0.3263 | 0.105 | 0.003 |

| Infant | 赤ちゃん | 0.2101 | 0.035 | < 0.001 |

| Sole of the foot (colloquial term) | 足裏 | − 0.2455 | 0.052 | < 0.001 |

| High fever | 高熱 | 0.1784 | 0.07 | 0.014 |

| Measles | 麻疹 | − 0.5895 | 0.126 | < 0.001 |

| Nasal mucus | 鼻水 | − 0.2792 | 0.05 | < 0.001 |

Adjusted R2 = 98.4%

Compared to period 1, the significant search terms in period 2 contained the same meanings and expanded informative search content. “Herpangina,” “nasal mucus,” “exhaustion,” “diarrhea,” “summer cold,” “young child,” “pediatric,” and “swelling” occurred in the original form. “Pain,” “reduce fever,” “oral cavity,” “chickenpox,” “itch,” and “sole of the foot” occurred in morphing or synonym forms. “Virus” was replaced by more specific infection sources in period 2, such as “adenovirus,” “entero-,” “coxsackie,” “mycoplasma,” “legionella,” and “hemolytic streptococcus.” Correspondingly, “adult” was superseded by other terms for susceptible populations, such as “child” and “infant” (Omit synonyms). Search terms related to susceptible sites, preventive measures, and treatment also were identified in period 2, such as “daycare center,” “kindergarten,” “handwashing,” “disinfection,” “hospital,” and “specialty drugs.” Multiple linear regression results corroborated the cross-correlation results and indicated that public awareness of HFMD might increase during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Discussion

This study presented trends and correlations between HFMD cases and RSV of “HFMD” from 2009 to 2021. Cross-correlation analyses were conducted between HFMD cases and search terms for RSV before and during the pandemic period. Additionally, multiple linear regressions were used to identify significant search terms for explaining HFMD cases in the two periods. Our results indicated that HFMD cases and RSV peaked around July in most years, except in 2020 and 2021, and surged after 2011 with peaks every 2 years before 2020. The search topic “HFMD” exhibited strong correlations with HFMD cases except in 2020, when the COVID-19 outbreak occurred. Furthermore, cross-correlation and multiple regression results revealed that the public might have improved their awareness of HFMD infection during the pandemic. To our knowledge, this study is the first to explain HFMD cases using Google search data and to examine changes in information-seeking behavior toward HFMD affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Google search data can supplement public health surveillance and help authorities respond rapidly to infectious diseases.

From 2009 to 2021, the RSV of “HFMD” coincided with the HFMD cases, except in 2020, which showed similar trends and peaks. In Japan, HFMD peaks generally occur in July [5]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, different from previous HFMD peaks disappeared in 2020 and lagged until November 2021. In 2020, Google Trends search data did not match the “HFMD” cases, with a relatively small peak in July. Despite a small peak in the RSV of the search topic “HFMD,” the volume was much lower than in previous years. In contrast, the Japanese government has implemented several measures to control COVID-19, which might potentially influence the spread of HFMD. Respiratory droplets and contact routes are the main infection routes in HFMD and COVID-19 [49, 50]. Therefore, the population susceptible to HFMD also stays safe by taking standard precautions during COVID-19, such as physical distancing, wearing a mask, regularly washing hands, and coughing into a bent elbow or tissue [51].

Based on the evidence provided by our results, the global pandemic might have enhanced public awareness of HFMD in addition to COVID-19. 73 (72.3%) search terms cross-correlated earlier with HFMD cases during COVID-19, and significant search terms detected in Period 2 contained more informative information. Previous studies demonstrated that the prevalence of respiratory infectious diseases reduced during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as influenza, varicella, herpes zoster, rubella, and measles [52–58]. This might have been due to adherence to non-pharmaceutical interventions and lower non-polio enterovirus activity during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to 2014–2019 [59]. Switzerland had an unprecedented complete absence of pediatric enteroviral meningitis in 2020 [60]. In Japan, community-acquired pneumonia [61] and influenza [62] admissions have reduced during the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 preventative actions and better personal hygiene are beneficial for preventing the spread of the disease. However, the prevalence of common diseases may rise as the public gradually complies less with infection control measures in the upcoming season [61]. Consistent with our results, a peak in HFMD infection and public interest reoccurred in November 2021. Continuous monitoring of HFMD is required, and public information-seeking behaviors may be helpful in public health surveillance.

Google search data was applied in our study to explain HFMD cases affected by COVID-19 instead of Baidu search data, which was used for real-time estimation of HFMD cases in China [15] and other categories of data for HFMD prediction or explanation [11–14]. In contrast to previous studies, we focused on the distinction between the information-seeking behavior of HFMD before and during COVID-19 and attempted to explain the HFMD cases using Google Trends data, which has the highest market share in Japan [17]. Many researchers have shown that Google search data represent public interest in a specific topic. However, Google search data should be used cautiously as a surveillance system, because large events can easily interfere with it. Combining fine-grained data, such as mobility data, could help develop surveillance systems that can effectively exclude biased or irrelevant information to respond rapidly [63].

Conclusion

This study described trends and correlations in HFMD cases with RSV of “HFMD” and identified significant search terms to explain HFMD infections before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that the prevalence of HFMD was abnormal during COVID-19, and the public might have enhanced awareness of HFMD infection affected by the pandemic. It is critical to continuously monitor resurgent common infections, as the public gradually reduces compliance with infection control measures. Public information seeking behavior using Google search data may be useful for public health surveillance.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, our findings are limited to those who used Google to search for health-related information, which may not represent the entire community. The results may be biased toward younger people, who are more digitally connected than older individuals, although the Google search engine market share in Japan is nearly 80% [17]. Second, Google Trends improved the geographical assignment and data collection systems in 2011, 2016, and 2022. Our results in the basic description of HFMD cases and “HFMD” RSV might be affected by them. Third, search data analysis is hypersensitive to large events; therefore, it is complementary instead of replacing traditional research methods. Fourth, the specific HFMD-related terms selected by Twitter may not represent all search terms in public use, especially hiragana, katakana, kanji, and alphabets used in Japan. Fifth, we used search data from 2016 to 2019 to represent the period before the COVID-19 pandemic owing to restrictions of Google Trends, which may not represent the entire period. Finally, during the process of backward elimination for regression model construction, significant terms may be eliminated because they are jointly insignificant. Although we can find potentially significant terms from all eliminated terms, it is not practical to conduct F-tests multiple times because multiple hypothesis testing leads to lower confidence levels. Hence, the current processing results were retained.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Counts of tokens calculated using "HFMD" related Tweets.

Additional file 2. Translation tables and interpretations.

Additional file 3. Search terms categories.

Additional file 4. Cross-correlation coefficients and model specification formulas.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- HFMD

Hand, foot, and mouth disease

- EV-A71

Enterovirus A71

- CV-A6

Coxsackievirus A6

- CV-A16

Coxsackievirus A16

- NIID

National Institute of Infectious Disease

- LDE

Logistic differential equation

- L-DNM

Landscape dynamic network marker

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- RSV

Relative search volume

Author contributions

QN, JL, MNT, and TA contributed to study conception and design. QN, ZZ, AB, KH, MO, and AK collected data. QN, JL, and ZZ participated in the data analysis and interpretation. QN and JL drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Japan Science and Technology for pioneering research initiated by the next generation (SPRING; grant number JPMJSP2110).

Availability of data and materials

We used publicly available data published by Google Trends (https://trends.google.com/trends/?geo=JP) and the National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan (https://www.niid.go.jp/niid/en/). All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published article (Additional file 5).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations (DECLARATION OF HELSINKI). Ethical approval and consent to participate were not necessary as the study was based on openly available aggregated data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Qian Niu and Junyu Liu contributed equally to this article

References

- 1.Huang J, Liao Q, Ooi MH, Cowling BJ, Chang Z, Wu P, et al. Epidemiology of recurrent hand, foot and mouth disease, China, 2008–2015. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:432. doi: 10.3201/eid2403.171303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang J, Hu T, Sun D, Ding S, Carr MJ, Xing W, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of hand, foot, and mouth disease in Shandong, China, 2009–2016. Sci Rep Sci Rep. 2017;7:8900. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09196-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puenpa J, Wanlapakorn N, Vongpunsawad S, Poovorawan Y. The history of enterovirus A71 outbreaks and molecular epidemiology in the Asia-Pacific region. J Biomed Sci. 2019;26:75. doi: 10.1186/s12929-019-0573-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biggs HM - Chapter 4. Hand, foot, & mouth disease. Yellow Book. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2020/travel-related-infectious-diseases/hand-foot-and-mouth-disease. Accessed 26 Sep 2022; 2020.

- 5.Koh WM, Bogich T, Siegel K, Jin J, Chong EY, Tan CY, et al. The epidemiology of hand, foot and mouth disease in Asia: a systematic review and analysis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35:e285–300. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.厚生労働省. 国立感染症研究所. 感染症週報(JAPAN IDWR), 11; 2009.

- 7.Fujimoto T, Iizuka S, Enomoto M, Abe K, Yamashita K, Hanaoka N, et al. Hand, foot, and mouth disease caused by coxsackievirus A6, Japan, 2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:337–339. doi: 10.3201/eid1802.111147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pavel K, Martina M, Dita S. Hand-foot-mouth disease in puerperium. Ceska Gynekol. 2022;87:47–49. doi: 10.48095/cccg202247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.IDWR. 年第 29号<注目すべき感染症>手足口病. https://www.niid.go.jp/niid/ja/hfmd-m/hfmd-idwrc/9017-idwrc-1929.html. Accessed 23 Aug 2022, 2014; 2019.

- 10.Sun BJ, Chen HJ, Chen Y, An XD, Zhou BS. The risk factors of acquiring severe hand, foot, and mouth disease: a meta-analysis. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2018;2018:2751457. doi: 10.1155/2018/2751457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rui J, Luo K, Chen Q, Zhang D, Zhao Q, Zhang Y, et al. Early warning of hand, foot, and mouth disease transmission: a modeling study in mainland. China PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:e0009233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu G, Feng H, Feng S, Zhao J, Xu J. Forecasting hand-foot-and-mouth disease cases using wavelet-based SARIMA–NNAR hybrid model. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0246673. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang X, Xie R, Liu Z, Pan Y, Liu R, Chen P. Identifying pre-outbreak signals of hand, foot and mouth disease based on landscape dynamic network marker. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(Suppl 1):6. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05709-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao Q, Liu Z, Xiang J, Tong M, Zhang Y, Wang S, et al. Forecast and early warning of hand, foot, and mouth disease based on meteorological factors: evidence from a multicity study of 11 meteorological geographical divisions in mainland China. Environ Res. 2021;192:110301. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao Y, Xu Q, Chen Y, Tsui KL. Using Baidu index to nowcast hand-foot-mouth disease in China: a meta learning approach. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:398. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3285-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.IDWR Surveillance Data Table 2022 week. https://www.niid.go.jp/niid/en/survaillance-data-table-english/11133-idwr-sokuho-data-e-2218.html. Accessed 23 Aug 2022, 18; 2022.

- 17.Search engine market share Japan. StatCounter global stats. https://gs.statcounter.com/search-engine-market-share/all/japan. Accessed 27 Sep 2022.

- 18.Europe, Asia, Nguyen C. Search engine marketing share around the world from US; 2008. https://www.chandlernguyen.com/blog/2008/11/29/search-engine-marketing-share-around-the-world-from-us-europe-and-asia/. Accessed 27 Sep 2022.

- 19.Eysenbach G. Infodemiology and infoveillance: framework for an emerging set of public health informatics methods to analyze search, communication and publication behavior on the Internet. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11:e11. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mavragani A, Ochoa G, Tsagarakis KP. Assessing the methods, tools, and statistical approaches in google trends research: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20:e270. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nuti SV, Wayda B, Ranasinghe I, Wang S, Dreyer RP, Chen SI, et al. The use of google trends in health care research: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e109583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0109583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mavragani A, Ochoa G. Google trends in infodemiology and infoveillance: methodology framework. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2019;5:e13439. doi: 10.2196/13439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pervaiz F, Pervaiz M, Abdur Rehman N, Saif U. FluBreaks: early epidemic detection from Google flu trends. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e125. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma D, Sandelski MM, Ting J, Higgins TS. Correlations in trends of sinusitis-related online google search queries in the United States. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2020;34:482–486. doi: 10.1177/1945892420905761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Memon SA, Razak S, Weber I. Lifestyle disease surveillance using population search behavior: feasibility study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e13347. doi: 10.2196/13347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mavragani A, Sampri A, Sypsa K, Tsagarakis KP. Integrating smart health in the US health care system: infodemiology study of asthma monitoring in the google era. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2018;4:e24. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.8726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tizek L, Schielein M, Rüth M, Ständer S, Pereira MP, Eberlein B, et al. Influence of climate on google Internet searches for pruritus Across 16 German cities: retrospective analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21:e13739. doi: 10.2196/13739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boehm A, Pizzini A, Sonnweber T, Loeffler-Ragg J, Lamina C, Weiss G, et al. Assessing global COPD awareness with Google Trends. Eur Respir J. 2019;53:1900351. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00351-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schootman M, Toor A, Cavazos-Rehg P, Jeffe DB, McQueen A, Eberth J, et al. The utility of Google Trends data to examine interest in cancer screening. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006678. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phillips CA, Barz Leahy A, Li Y, Schapira MM, Bailey LC, Merchant RM. Relationship Between state-level google online search volume and cancer incidence in the United States: retrospective study. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20:e6. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linkov F, Bovbjerg DH, Freese KE, Ramanathan R, Eid GM, Gourash W. Bariatric surgery interest around the world: what Google Trends can teach us. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:533–538. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dreher PC, Tong C, Ghiraldi E, Friedlander JI. Use of google trends to track online behavior and interest in kidney stone surgery. Urology. 2018;121:74–78. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2018.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taira K, Hosokawa R, Itatani T, Fujita S. Predicting the number of suicides in Japan using Internet search queries: vector autoregression time series model. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021;7:e34016. doi: 10.2196/34016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Husnayain A, Shim E, Fuad A, Su EC-Y. Predicting new daily COVID-19 cases and deaths using search engine query data in South Korea From 2020 to 2021: infodemiology study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23:e34178. doi: 10.2196/34178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higgins TS, Wu AW, Sharma D, Illing EA, Rubel K, Ting JY, et al. Correlations of online search engine trends With coronavirus disease (COVID-19) incidence: infodemiology study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6:e19702. doi: 10.2196/19702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pullan S, Dey M. Vaccine hesitancy and anti-vaccination in the time of COVID-19: a Google Trends analysis. Vaccine. 2021;39:1877–1881. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diaz P, Reddy P, Ramasahayam R, Kuchakulla M, Ramasamy R. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy linked to increased internet search queries for side effects on fertility potential in the initial rollout phase following Emergency Use Authorization. Andrologia. 2021;53:e14156. doi: 10.1111/and.14156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.An L, Russell DM, Mihalcea R, Bacon E, Huffman S, Resnicow K. Online search behavior related to COVID-19 vaccines: infodemiology study. JMIR Infodemiol. 2021;1:e32127. doi: 10.2196/32127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Han J, Kamat S, Agarwal A, O’Hagan R, Tukel C, Owji S, et al. Correlation Between interest in COVID-19 hair loss and COVID-19 surges: analysis of google trends. JMIR Dermatol. 2022;5:e37271. doi: 10.2196/37271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kardeş S, Erdem A, Gürdal H. Public interest in musculoskeletal symptoms and disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic: infodemiology study. Z Rheumatol. 2022;81:247–252. doi: 10.1007/s00393-021-00989-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knipe D, Gunnell D, Evans H, John A, Fancourt D. Is Google Trends a useful tool for tracking mental and social distress during a public health emergency? A time-series analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;294:737–744. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen SA, Ebrahimian S, Cohen LE, Tijerina JD. Online public interest in common malignancies and cancer screening during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. J Clin Transl Res. 2021;7:723–732. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Akpan IJ, Aguolu OG, Kobara YM, Razavi R, Akpan AA, Shanker M. Association between what people learned About COVID-19 using web searches and their behavior toward public health guidelines: empirical infodemiology study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23:e28975. doi: 10.2196/28975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adelhoefer S, Berning P, Solomon SB, Maybody M, Whelton SP, Blaha MJ, et al. Decreased public pursuit of cancer-related information during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Cancer Causes Control. 2021;32:577–585. doi: 10.1007/s10552-021-01409-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benesty J, Chen J, Huang Y, Cohen I. Pearson correlation coefficient. In: Cohen I, Huang Y, Chen J, Benesty J, editors. Noise reduction in speech processing. Berlin: Springer; 2009. pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bourke. Cross correlation. Cross Correlation. Auto Correlation—2D Pattern.

- 47.Tranmer E. Multiple linear regression. Cathie Marsh Centre for Census.

- 48.Akossou P. Impact of data structure on the estimators R-square and adjusted R-square in linear regression. Int J Math Comput. 2013;20(3):84–93. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.CDC. Causes & transmission. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/hand-foot-mouth/about/transmission.html. Accessed 28 Sep 2022.

- 51.Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): How is it transmitted? https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-how-is-it-transmitted Accessed 28 Sep 2022.

- 52.Sakamoto H, Ishikane M, Ueda P. Seasonal influenza activity during the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in Japan. JAMA. 2020;323:1969–1971. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu D, Liu Q, Wu T, Wang D, Lu J. The impact of COVID-19 control measures on the morbidity of varicella, herpes zoster, rubella and measles in Guangzhou, China. Immun Inflam Dis. 2020;8:844–846. doi: 10.1002/iid3.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu D, Lu J, Liu Y, Zhang Z, Luo L. Positive effects of COVID-19 control measures on influenza prevention. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;95:345–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kies KD, Thomas AS, Binnicker MJ, Bashynski KL, Patel R. Decrease in enteroviral meningitis: an unexpected benefit of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) mitigation? Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:e2807–e2809. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Veiga ABGD, Martins LG, Riediger I, Mazetto A, Debur MDC, Gregianini TS. More than just a common cold: endemic coronaviruses OC43, HKU1, NL63, and 229E associated with severe acute respiratory infection and fatality cases among healthy adults. J Med Virol. 2021;93:1002–1007. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li Q, Wang J, Lv H, Lu H. Impact of China’s COVID-19 prevention and control efforts on outbreaks of influenza. BioSci Trends. 2021;15:192–195. doi: 10.5582/bst.2021.01242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wan WY, Thoon KC, Loo LH, Chan KS, Oon LLE, Ramasamy A, et al. Trends in respiratory virus infections during the COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore, 2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2115973. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.15973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kuo SC, Tsou HH, Wu HY, Hsu YT, Lee FJ, Shih SM, et al. Nonpolio enterovirus activity during the COVID-19 pandemic, Taiwan, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:306. doi: 10.3201/eid2701.203394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stoffel L, Agyeman PKA, Keitel K, Barbani MT, Duppenthaler A, Kopp MV, et al. Striking decrease of enteroviral meningitis in children During the COVID-19 pandemic. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2021;8:ofab115. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofab115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yan Y, Tomooka K, Naito T, Tanigawa T. Decreased number of inpatients with community-acquired pneumonia during the COVID-19 pandemic: a large multicenter study in Japan. J Infect Chemother. 2022;28:709–713. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2022.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hirose T, Katayama Y, Tanaka K, Kitamura T, Nakao S, Tachino J, et al. Reduction of influenza in Osaka, Japan during the COVID-19 outbreak: a population-based ORION registry study. IJID Reg. 2021;1:79–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijregi.2021.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arık SÖ, Shor J, Sinha R, Yoon J, Ledsam JR, Le LT, et al. A prospective evaluation of AI-augmented epidemiology to forecast COVID-19 in the USA and Japan. Npj Digit Med. 2021;4:146. doi: 10.1038/s41746-021-00511-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Counts of tokens calculated using "HFMD" related Tweets.

Additional file 2. Translation tables and interpretations.

Additional file 3. Search terms categories.

Additional file 4. Cross-correlation coefficients and model specification formulas.

Data Availability Statement

We used publicly available data published by Google Trends (https://trends.google.com/trends/?geo=JP) and the National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan (https://www.niid.go.jp/niid/en/). All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published article (Additional file 5).