Abstract

Introduction

The identification of dementia cases through routinely collected health data represents an easily accessible and inexpensive method to estimate the prevalence of dementia. In Italy, a project aimed at the validation of an algorithm was conducted.

Methods

The project included cases (patients with dementia or mild cognitive impairment [MCI]) recruited in centers for cognitive disorders and dementias and controls recruited in outpatient units of geriatrics and neurology. The algorithm based on pharmaceutical prescriptions, hospital discharge records, residential long‐term care records, and information on exemption from health‐care co‐payment, was applied to the validation population.

Results

The main analysis was conducted on 1110 cases and 1114 controls. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values in discerning cases of dementia were 74.5%, 96.0%, 94.9%, and 79.1%, respectively, whereas in detecting cases of MCI these values were 29.7%, 97.5%, 92.2%, and 58.1%, respectively. The variables associated with misclassification of cases were also identified.

Discussion

This study provided a validated algorithm, based on administrative data, which can be used to identify cases with dementia and, with lower sensitivity, also early onset dementia but not cases with MCI.

Keywords: algorithm, Dementia, early onset dementia, health electronic data, mild cognitive impairment, prevalence, validation

1. INTRODUCTION

Dementia affects ≈50 million people worldwide, and this number will almost double every 20 years, reaching 82 million in 2030 and 152 million in 2050. 1 Dementia is one of the costliest conditions to society. The economic impact is attributed to social care costs (care professionals, in community and in residential home settings), health costs, and informal family care costs. 2 In 2013, Alzheimer's Disease International (ADI) encouraged governments around the world to develop and implement National Plans for Dementia (PND) as they are the only powerful tools to improve dementia care and support. 3 In October 2014 the Italian Dementia National Plan was approved, listing among its major objectives the development of a national dementia information system with the aim of evaluating the impact of the disease, so to organize resources and services according to the different local needs. 4

Observational epidemiological studies on the prevalence and incidence of dementia are expensive and time‐consuming. Although they can provide many elements of clinical characterization of different forms of dementia, they typically do not combine community‐dwelling and institutionalized populations. 5 From a public health perspective, administrative health records have emerged as a new opportunity to study the epidemiology of dementia, since they represent an easily accessible, rapid, and inexpensive source of data. However, the assessment of diagnostic accuracy of dementia in routinely collected health care data requires specific validation studies. 6 A recent systematic review on health care data validation for dementia analyzed 27 studies conducted in high‐income countries (North America, Europe, Australia). The authors showed a wide variation in the results of validation studies, at least partly reflecting the heterogeneity in study methodologies, settings, and the data sets they assessed. The positive predictive values ranged between 33% and 100%, whereas the sensitivity values were between 21% and 86%. The authors suggested that the use of algorithms based on administrative data should be validated in their own setting‐specific population. 7 In a retrospective study conducted in Canada, medical records from family physicians were used as a reference standard to evaluate the accuracy of 300 algorithms applied to identify adults older than 65 years of age with Alzheimer's disease (AD) and related dementia. The highest performance was obtained with the algorithm based on hospitalizations, physician claims, and prescription‐filled data (sensitivity 79.3%; specificity 99.1%; positive predictive value 80.4%; negative predictive value 99.0%). 8

In Italy, a validation study was conducted with 120 patients with dementia in the community setting, using data from the medical records of general practitioners as the reference standard. The authors applied three distinct algorithms using a different combination of administrative data (therapy, neurological visit, brain computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging [CT/MRI], neuropsychological tests, and hospital discharge). 9 The achieved sensitivity was between 52.5% and 90.8% and the specificity was between 70.6% and 97.9%. The authors highlighted that some administrative health records (neurological visits or brain CT/MRI scans) are non‐specific for tracking patients with dementia, since they can be carried out for many other neurological conditions, and concluded that the algorithms did not show sufficient accuracy in identifying patients with dementia. 9

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT

Systematic Review: The authors reviewed the literature using traditional sources (e.g., PubMed). Several recent publications have investigated the use of routinely collected health care data to identify cases of dementia, showing high heterogeneity between validation studies and a wide variation in results. The relevant publications are cited appropriately.

Interpretation: The study showed a good sensitivity and an excellent specificity in identifying cases of dementia in line with the evidence reported in the literature, whereas it is not adequate to intercept cases of mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Moreover, the algorithm is useful for identifying early onset dementia.

Future Directions: To obtain better estimates of cases with dementia and MCI in the general population, development and validation of algorithms based on a larger number of administrative data in the context of primary care should be proposed.

The aim of the present study was to validate an algorithm based on health administrative data. Cases with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia (early and late onset) identified in centers for cognitive disorders and dementias (CCDDs) were used as the reference standard. Controls without MCI or dementia were recruited in the same clinical setting.

To our knowledge, this is the first study conducted in Italy in a large sample aimed at validating an algorithm for identifying dementia cases in a specific clinical setting, where diagnosis was provided by experts, and with the inclusion of MCI and early onset dementia (EOD).

2. METHODS

2.1. Study population

This is a multicenter, retrospective validation study conducted in four Italian regions (Campania in the South, Toscana and Lazio in the Center, and Piemonte in the North of Italy). Cases were identified in the archive of the CCDDs retrospectively and consecutively in a 5‐year period starting from December 31, 2016, including patients who received a diagnosis of dementia or MCI, 50 years of age and older. The CCDDs represent the memory clinics and are included in an integrated network of services for dementia (i.e., home care, day center, nursing home). Specifically, the CCDDs are currently dedicated to the diagnosis, treatment, and management of patients with dementia and other cognitive disorders. 10

For the purpose of this study, the specialists of each participating center reviewed MCI and dementia diagnoses recorded in their clinical database. The following clinical criteria were homogeneously applied: Consensus Conference of 2004 for MCI 11 ; Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM‐5) criteria for Dementia 12 ; National Institute on Aging (NIA) for Alzheimer's disease and mixed dementia 13 ; Gorelick et al., 14 for vascular dementia; Nearly et al., 15 for frontotemporal dementia (FTD); Rascovsky et al., 16 for behavioral variants of FTD; Gorno‐Tempini et al., 17 for primary aphasia of FTD; McKeith et al. 18 for Lewy body dementia; and Emre et al. 19 for Parkinson disease.

Controls subjects without dementia or MCI were recruited retrospectively and consecutively in a 5‐year period starting from December 31, 2016 in outpatient units of geriatrics or neurology located in the same outpatient clinics in which the CCDDs enrolled the cases. Controls were selected if having a normal cognitive profile evaluation according to routine clinical practice and were excluded if having a diagnosis of neurodegenerative disease. Controls were matched with cases by sex and age over a range of ±3 years. All cases and controls were alive and a resident in one of the four participating regions on December 31, 2016.

The baseline collected information included sociodemographic characteristics, comorbidities, current therapies, and Mini‐Mental Status Examination (MMSE); in addition, for cases only, data were gathered on the clinical form of dementia, treatment for dementia, symptoms, instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), basic ADLs (BADLs), and having a family history of dementia.

The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional ethics committees at all collaborating institutions. Informed consent was not necessary.

2.2. Administrative data sources and algorithm

In Italy, all citizens are covered by a universal public health system and several sources of routine administrative data linkable by anonymous unique identification code are available on the regional level, and partly on the national level as well. In this study, four data sources were used to identify cases of dementia in the participating regions, between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2016. The electronic administrative database covered a total of 8,250,942 residents 50 years of age and older (2,003,836 for Campania, 1,672,820 for Toscana, 2,461,597 for Lazio, and 2,112,689 for Piemonte).

(1) Prescription drug records include all the prescriptions reimbursed by the health care system, dispensed by both private and public community pharmacies. Prescriptions are coded following the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system. We searched for prescriptions of galantamine (ATC: N06DA04), rivastigmine (N06DA03), donepezil (N06DA02), and memantine (N06DX0). (2) The Hospital Discharge Registry (HDR) gathers data from all public and private hospitals, including clinical and administrative data regarding all types of admission, ordinary, long‐stay and day‐hospital (less than 24 hours of stay). Diagnoses and procedures are coded using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9‐CM). The following ICD‐9‐CM codes were used to identify cases of dementia and MCI, in primary or secondary diagnoses: 290.x, 291.2, 294.0–294.21, 292.82, 331.0–331.2, 331.5, 331.7, 331.8, 331.82–331.9, 046.1 (the code 331.83 is specific for MCI). (3) Information on exemption from health‐care co‐payment is retrieved by the disease‐specific Exemption Registry. Records with exemption codes 011 for dementia or 029 specific for AD (National codification system) were selected. (4) Data on residents in long‐term care facilities (LTCFs) were used, with indication of cognitive deficit in the individual record.

Deterministic record linkage within and between data sources, was conducted at the regional level by an anonymous unique identification code for all subjects in the study population used as the validation sample.

Based on the four data sources, a case of dementia or MCI was defined if having at least two different prescriptions of drugs for dementia within 12 months OR at least one hospital discharge with primary or secondary diagnoses of dementia or MCI OR if the subjects had the exemption from health‐care co‐payment specific for the disease OR if resident in LTCF with cognitive deficit reported (Figure S1). The LTCF registry was available only for three regions: Piemonte, Campania, and Toscana. Subjects were classified as not having dementia or MCI if none of the previous criteria were satisfied in the entire 5‐year study period. The validation study involved the comparison of the reference population, that is, the cases (patients with dementia or MCI) recruited at the CCDDs, and the controls (subjects without dementia or MCI) recruited at the geriatric and neurological centers, with the classification obtained by the search algorithm strategy.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed using a t‐test for continuous variables and chi‐square test for proportions. We calculated sensitivity and specificity, positive and negative predictive values (PPVs and NPVs), likelihood ratio positive and negative, along with the overall accuracy measure area under the receiver‐operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC) based on a comparison of the automated search algorithm classification with the clinical evaluation, considered the reference standard. PPVs and NPVs were provided for literature comparison, even if both markers, especially PPV, depend on the prevalence of the disease, 20 which, in our study, does not reflect the prevalence in the general population. The assessment of algorithm performance and in‐depth analyses were performed using data of three of the four regions, because of a lack of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics for most of subjects in Toscana. However, the measures of diagnostic accuracy were re‐calculated also including data from Toscana. The analyses were stratified to assess the potential differences by sex and age (50–64, 65–74, and ≥75 years). Moreover, the algorithm accuracy was evaluated for MCI, dementia, and early onset dementia (adults 50–64 years with dementia), considering their own matched controls.

Finally, to improve case ascertainment, a predictive model was performed by logistic regression, including algorithm classification as a factor, sex, and age. Odds ratios (ORs) and the AUC index were provided. The added value of age and sex was tested using the likelihood ratio test.

To characterize the sensitivity, an analysis of discordant cases was performed to assess the characteristics associated with misclassification comparing true‐positive cases versus false‐negative cases by logistic regression. The following characteristics were considered in a univariate model: age, sex, education, duration of the disease (years from diagnosis), type of dementia (considering two different classifications, one variable classified in two categories: dementia vs MCI, and another one in three categories AD vs other forms of dementia vs MCI), having a family history of dementia, IADLs, BADLs, MMSE adjusted, comorbidity, and treatment for dementia. All variables that were statistically significant at 5% in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate model.

Finally, the algorithm was applied to the resident population of the four regions at December 31, 2016, separately for the 50–64 age group and the group 65 years and older, to estimate the prevalence of dementia and MCI. The estimates were compared with the expected value based on age‐ and sex‐specific prevalence of dementia from Chiari et al. 21 for the population 50–64 years of age and Bacigalupo et al. 22 for adults older than 65 years.

The present study follows the guidelines for assessing the quality of validation studies of health administrative data 23 based on the STARD 2015 guidelines (Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy). 24

3. RESULTS

A total of 1354 cases and 1254 controls were identified in 24 clinical centers distributed in Piemonte, Lazio, and Campania. After matching cases and controls by sex and age, quality check, and the availability of the identification code used for record linkage with administrative data, a total of 1110 cases and 1114 controls were retained, resident and alive on December 31, 2016. Overall, 60.3% of the sample were female and the mean age was 76.0 (SD 7.9). Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of cases and controls are displayed in Table 1. Among cases, Alzheimer's was the prevalent form of dementia (48.5%), 63.6% had duration of the disease less than 3 years, and one fourth had a family history of dementia (Table 2). As for anti‐dementia drugs, 82.7% of cases with dementia and 19.0% of cases with MCI were using cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine!

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the validation population

| Cases (1110) | Controls (1114) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia (952) | MCI (158) | Total cases | |||

| Characteristics | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | P value * |

| Region | |||||

| Campania | 422 (44.3) | 53 (33.5) | 475 (42.8) | 470 (42.2) | |

| Lazio | 301 (31.6) | 63 (39.9) | 364 (32.8) | 373 (33.5) | .937 |

| Piemonte | 229 (24.1) | 42 (26.6) | 271 (24.4) | 271 (24.3) | |

| Sex (Male) | 370 (38.9) | 66 (41.8) | 436 (39.3) | 447 (40.1) | .683 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 76.8 ± 7.8 | 73.5 ± 8.0 | 76.3 ± 7.9 | 75.6 ± 7.9 | .050 |

| 50‐64 years | 68 (7.1) | 21 (13.3) | 89 (8.0) | 93 (8.4) | .163 |

| 65‐74 years | 260 (27.3) | 57 (36.1) | 317 (28.6) | 357 (32.0) | |

| 75+ years | 624 (65.6) | 80 (50.6) | 704 (63.4) | 554 (59.6) | |

| Education | |||||

| None | 136 (14.3) | 9 (5.7) | 145 (13.0) | 61 (5.5) | |

| Primary | 413 (43.4) | 44 (27.9) | 457 (41.2) | 295 (26.5) | |

| Lower secondary | 177 (18.6) | 60 (38.0) | 237 (21.4) | 204 (18.3) | <.001 |

| Upper secondary | 136 (14.3) | 28 (17.7) | 164 (14.8) | 162 (14.6) | |

| Post‐secondary | 47 (4.9) | 10 (6.3) | 57 (5.1) | 56 (5.0) | |

| Not available | 43 (4.5) | 7 (4.4) | 50 (4.5) | 335 (30.1) | |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| Cardiovascular and respiratory | 668 (70.2) | 112 (70.9) | 780 (70.3) | 298 (73.3) | .119 |

| Endocrine‐metabolic system | 335 (35.2) | 72 (45.6) | 407 (36.7) | 424 (38.1) | .497 |

| Gastrointestinal and urinary system | 171 (18.0) | 31 (19.6) | 202 (18.2) | 203 (18.2) | .988 |

| Active malignant oncology | 26 (2.7) | 2 (1.3) | 28 (2.5) | 30 (2.7) | .801 |

| Other | 237 (24.9) | 54 (34.2) | 291 (26.2) | 321 (28.8) | .170 |

| MMSE adjusted †(mean ± SD) | 16.1 ± 6.0 | 25.7 ± 2.7 | 17.5 ± 6.6 | 27.1 ± 2.3 | <.001 |

Available for 1087 cases and 558 controls.

P value for comparison of cases versus controls.

Abbreviation: MMSE, mini mental state examination.

TABLE 2.

Clinical characteristics of cases with dementia and MCI

| Dementia (952) | MCI (158) | Total cases (1110) | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Clinical form of dementia | ||||

| Alzheimer's disease | 462 (48.5) | |||

| Mixed form | 151 (18.9) | |||

| Vascular | 66 (6.9) | |||

| Frontotemporal | 32 (3.4) | |||

| Parkinson | 8 (0.8) | |||

| DLB | 6 (0.6) | |||

| Other forms | 22 (2.3) | |||

| Not available | 205 (21.5) | |||

| Duration of disease | ||||

| 1 year or less | 228 (24.0) | 65 (41.1) | 293 (26.4) | |

| 2‐3 years | 356 (37.4) | 57 (36.1) | 413 (37.2) | <.001 |

| 4 years and more | 284 (29.8) | 14 (8.9) | 298 (26.9) | |

| Not available | 84 (8.8) | 22 (13.9) | 106 (9.5) | |

| Familiarity | 202 (21.4) | 28 (17.7) | 230 (24.6) | .287 |

| BADLs (mean ± SD) | 3.9 ± 1.7 | 5.7 ± 0.8 | 4.1 ± 1.7 | <.001 |

| IADLs (mean ± SD) | 2.6 ± 2.0 | 6.5 ± 1.9 | 3.2 ± 2.4 | <.001 |

| Current treatment for dementia | ||||

| Memantine | 383 (40.2) | 10 (6.3) | 393 (35.4) | <.001 |

| Donepezil | 236 (24.8) | 16 (10.1) | 252 (22.7) | <.001 |

| Rivastigmine | 204 (21.4) | 7 (4.4) | 211 (19.0) | <.001 |

| Galantamine | 40 (4.2) | 4 (2.5) | 44 (4.0) | .319 |

| Atypical antipsychotics | 152 (16.0) | 6 (3.8) | 158 (14.2) | <.001 |

| Typical antipsychotics | 131 (13.8) | 7 (4.4) | 138 (12.4) | .001 |

| Antidepressants | 338 (35.0) | 64 (40.5) | 402 (36.2) | .226 |

| Benzodiazepines | 104 (10.9) | 27 (17.1) | 131 (11.8) | .026 |

| Antiepileptic | 58 (6.1) | 8 (5.1) | 66 (6.0) | .612 |

| Hypnotics – No Benzodiazepine | 38 (4.0) | 3 (1.9) | 41 (3.7) | .196 |

| Nutraceuticals | 116 (12.2) | 53 (33.5) | 169 (15.2 | <.001 |

Note: Familiarity and BADLs not available for 10 cases with dementia; IADLs not available for 27 cases with dementia and 1 case with MCI.

*P value for comparison dementia vs MCI.

DLB, Dementia lewy body; BADLs, basic activities of daily living; IADLs, instrumental activities of daily living.

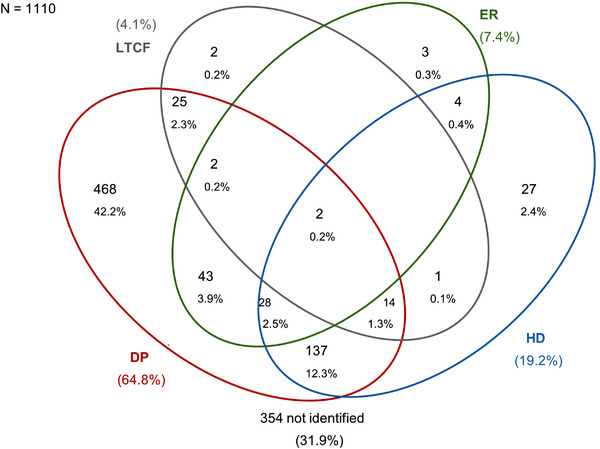

Overall, 756 cases (68.1% of the total) were correctly identified by the algorithm, whereas only 42 controls (3.8% of the total) were identified as cases. The main source of data in the identification of cases was drug prescriptions detecting 64.8% of cases, followed by hospital discharge (19.2%) and exemption from health care co‐payment (7.4%). A marginal contribution was provided by the LTCF database that identified 4.1% of the cases but added only two subjects to those identified by the other sources (Figure 1). If considering only the data of regions that used LTCF records, that is, Campania and Piemonte, 6.2% of cases were identified by this source, but adding only a mere 0.3% of cases not identified by the other sources.

FIGURE 1.

Contribution of data sources to dementia/MCI cases identification: Venn diagram. HD, hospital discharge; DP, drug prescription; ER, exemption registry; LTCF, residents in long‐term care facilities. The percentage of cases captured by long‐term care (LCT) was 6.2%, if excluding cases from Latium for which this source of data was not available

The sensitivity and specificity of the algorithm were 68.1% (95% confidence interval [CI] 65.3–70.8) and 96.2% (95% CI: 94.9–97.3), respectively, and the AUC was 82.2% (95% CI: 80.7–83.7). Algorithm performance varied between age groups and was higher in the 75+ years age group (AUC = 84.6, 95% CI: 82.8–86.4). No relevant difference was observed by sex (Table 3). The analysis was repeated including data from Toscana (610 cases and 303 controls) confirming substantially our findings. Sensitivity and specificity were respectively 65.6% (95% CI: 63.3–67.8) and 93.6% (95% CI: 92.2–94.8), whereas AUC was 79.6% (95% CI: 78.3–80.9), with no differences between gender and better performance in the oldest age group (Table S1). However, a huge variability was observed in algorithm performance between regions, with sensitivity ranging between 52.6% and 81.6%, and specificity between 83.7% and 97.8%. The region showing the worst performance had the highest frequency of cases with a short duration of the disease (34.5% with less than 1 year) and the highest frequency of patients having a family history of dementia (31.0% of cases). The algorithm showed a better performance in the identification of dementia cases compared to MCI, with an AUC of 85.3% (95% CI: 83.7–86.8) and 63.6% (95% CI: 59.8–67.4) respectively, and a sensitivity of 74.5% and 29.7%. Moreover, in young adults with dementia, the sensitivity was 66.2% (95% CI: 53.7–77.2) (Table 3). To improve the algorithm performance, a logistic model was performed adding age and sex in the model along with the algorithm classification as a factor. The corresponding AUC was slightly higher (83.8, 95% CI: 82.0–85.5) than the AUC considering only the algorithm, due to the additional value of age. This was confirmed also by the likelihood ratio test performed for age (p = .001) and sex (p = .824).

TABLE 3.

Accuracy of the algorithm in classifying cases with dementia/MCI applied to the reference population

| SE (95% CI) | SPE (95% CI) | LR+ | LR‐ | PPV | NPV | AUC (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole study population | 68.1 (65.3, 70.8) | 96.2 (94.9, 97.3) | 18.1 | 0.33 | 94.7 | 75.2 | 82.2 (80.7,83.7) |

| Algorithm stratified by: | |||||||

| Male | 66.5 (61.9, 70.9) | 96.4 (94.3, 97.9) | 18.6 | 0.35 | 94.8 | 74.7 | 81.4 (79.1, 83.8) |

| Female | 69.1 (65.5, 72.6) | 96.1 (94.3, 97.4) | 17.7 | 0.32 | 94.7 | 75.5 | 82.6 (80.7, 84.5) |

| Age 50–64 years | 53.9 (43.0, 64.6) | 98.9 (94.2, 100) | 50.2 | 0.47 | 98.0 | 69.2 | 76.4 (71.1, 81.7) |

| Age 65–74 years | 58.4 (52.7, 63.8) | 98.0 (96.0, 99.2) | 29.8 | 0.42 | 96.4 | 72.6 | 78.2 (75.4, 81.0) |

| Age 75+ years | 74.3 (70.9, 77.5) | 94.9 (92.9, 96.4) | 14.5 | 0.27 | 93.9 | 77.7 | 84.6 (82.8, 86.4) |

| Algorithm validated for: | |||||||

| MCI | 29.7 (22.7, 37.5) | 97.5 (93.6, 99.3) | 11.8 | 0.72 | 92.2 | 58.1 | 63.6 (59.8, 67.4) |

| Dementia | 74.5 (71.6, 77.2) | 96.0 (94.6, 97.2) | 18.7 | 0.27 | 94.9 | 79.1 | 85.3 (83.7, 86.8) |

| Dementia 50–64 years | 66.2 (53.7, 77.2) | 98.6 (92.7, 100) | 49.0 | 0.34 | 97.8 | 76.0 | 82.4 (76.6, 88.2) |

| Dementia 65+ years | 75.1 (72.1, 77.9) | 95.8 (94.3, 97.0) | 17.9 | 0.26 | 94.7 | 79.3 | 85.6 (84.0, 87.1) |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the receiver‐operating characteristic (ROC) curve (%); LR+, positive likelihood ratio; LR‐, negative likelihood ratio; NPV, negative predictive value (%); PPV, positive predictive value (%); SE, sensitivity (%); SPE, specificity (%).

Cases and controls were defined using drug prescriptions, hospital discharge, exemption from healthcare co‐payment and residents in long‐term care facilities (LTCF).

The comparison of characteristics of correctly identified cases (true positive) with cases not identified (false negative) showed the following characteristics associated to misclassification of cases (Table 4): age (OR = 0.97, p = .006), years of education (OR = 0.94, p = .005), having a family history of dementia (OR = 1.87, p = .001), diagnosis of MCI versus dementia (OR = 2.04, p = .015), duration of disease (OR = 7.27, p < .001 in 1 year or less and OR = 2.02, p = .003 in 2–3 years vs more than 4 years), BADLs (OR = 0.90, p = .066), MMSE adjusted (OR = 1.05, p = .012), and current treatment for dementia (OR = 0.28, p < .001).

TABLE 4.

Identification of the characteristics associated with misclassification of cases by multivariate logistic regression

| OR | (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.97 | (0.95, 0.99) | .006 |

| Education (years) | 0.94 | (0.90, 0.98) | .005 |

| Family history (Y vs N) | 1.87 | (1.30, 2.68) | .001 |

| Diagnosis (MCI vs Dementia) | 2.04 | (1.15, 3.62) | .015 |

| Duration of disease a (vs ≥4 years) | |||

| 1 year or less | 7.27 | (4.53, 11.68) | <.001 |

| 2–3 years | 2.02 | (1.28, 3.19) | .003 |

| BADLs | 0.90 | (0.80, 1.01) | .066 |

| MMSE adjusted | 1.05 | (1.01, 1.08) | .012 |

| Use of antidementia treatment (Y vs N) | 0.28 | (0.19, 0.42) | <.001 |

Years from diagnosis.

Finally, the algorithm was applied to the whole population resident in the four regions, corresponding to about 30% of the Italian resident population. The overall prevalence estimated by the algorithm was 16.0 per 1000 residents ages 50 years and older; it was 30.1 per 1000 residents ages 65+ and 1.1 per 1000 residents aged 50–64 years (Table 5). The comparison with data from the literature showed a prevalence estimate in the 65+ age group 60% lower than the expected, whereas for the 50–64 year age group the estimate was 31% lower.

TABLE 5.

Estimated prevalence (per 1000 residents) by the search algorithm and comparison with estimates expected using data by literature

| 50–64 aa | ≥65 aa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | total | Male | Female | total | |

| Cases identified | 2386 | 2161 | 4547 | 42,710 | 88,288 | 130,998 |

| Prevalence estimate | 1.19 | 1.01 | 1.10 | 22.8 | 35.7 | 30.1 |

| Cases expected a | 3106 | 3506 | 6609 | 95,971 | 235,522 | 331,493 |

| Prevalence expected | 1.55 | 1.64 | 1.59 | 51.2 | 95.2 | 76.2 |

| Ratio estimate/expected | 0.77 | 0.62 | 0.69 | 0.45 | 0.37 | 0.40 |

The sex‐age specific prevalence by Chiari et al. (2021) was applied for age 50–64 years; the sex‐age specific prevalence by Bacigalupo et al. (2018) was applied for age 65 and over.

4. DISCUSSION

The algorithm developed in this study showed a better performance in identifying cases with dementia (AUC: 85.3%) compared to cases with MCI (AUC: 63.6%), in line with the evidence reported in the literature. 7 , 25 An easy and quick tool is now validated to estimate the prevalence of dementia over time in four large regions where about 30% of the total Italian population resides, and it could be adopted in all Italian regions. Our study showed that the algorithm could also be used to detect early onset dementia, even if with lower sensitivity, whereas it is not adequate to intercept cases of MCI.

Subjects with MCI, a condition that usually precedes the onset of dementia, may not take specific medications for dementia, are usually not hospitalized and do not reside in a long‐term facility, and do not have a specific exemption code in Italy. In fact, the sensitivity value for patients with MCI is essentially due to the off‐label use of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine that allowed the identification of 37 patients (23.4% of the total) in the database of drugs prescriptions. The low sensitivity for MCI has also been documented in a study carried out in intensive care units where patients with MCI were identified from the electronic medical records with a sensitivity of only 43.4%. 25

The algorithm we propose showed the highest sensitivity in the elderly age group (75 years of age and older), suggesting that from this age onward the clinical conditions of individuals are more easily intercepted by the health administrative databases used in this study.

However, the sensitivity of the algorithm is not fully satisfactory, partially because the study population is referring to the community setting (patients and controls living to home). In fact, most of the subjects included were incident cases (24% had a duration of disease of 1 year or less) and not living in the LTCF, and therefore were not yet registered in the administrative data used in our study. Contrary to the available evidence, 7 we did not report a difference in the validity of the algorithm based on different clinical forms of dementia (e.g., Alzheimer's dementia and vascular dementia). This could also be due to a percentage of 22% of missing diagnoses of clinical forms of dementia in our study.

An in‐depth analysis of cases (MCI or dementia) made it possible to identify the variables that are most commonly associated with misclassification of cases (false negatives). Cases not identified by the algorithm tend to be younger, less educated, and with a positive family history of dementia, diagnosis of MCI, shorter duration of disease, a better level of autonomy, more preserved cognitive functions, and lower use of anti‐dementia drugs (Table 4). Similar results were obtained in a study carried out by Gallini et al. 26 The observed variability between regions in the algorithm performance was explained primarily by the differences in the characteristics of the enrolled populations at the regional level, especially family history of dementia and duration of the disease; both variables are strongly associated with misclassification of cases (Table 4).

In this context, it is evident that the application of this algorithm to the currently collected administrative data allows one to partially intercept cases with dementia in a specific territory.

We observed an underestimation of 31% for the prevalence of early‐onset dementia compared to the expected, and 60% for the prevalence of dementia in patients 65 years of age or older. These data should be considered with caution for two main reasons: (1) the algorithm should identify subjects with MCI and dementia, but the resulting prevalence estimate was compared to the estimates based on data available in the literature limited to dementia prevalence only; (2) for Lazio, the records on residential settings were not available, so, for this region, the underestimation could be even more pronounced. However, we highlighted that the population with MCI is unlikely to be captured by the algorithm, and that the contribution of data on residential setting to intercept cases of dementia or MCI was minimal (6.2%). Moreover, for the 50–64 age group, the expected prevalence was based on data of an Italian study referred to a limited area (province of Modena) in a single region, and thus could be not fully representative at the national level. For the age 65 years and over, the prevalence estimated by a meta‐analysis of European studies was applied. 22

Overall, this underestimation is explained by the fact that in this study we considered only four types of administrative data present in the New National Health Information System, which, indeed, includes many more sources of data such as outpatient specialist, home care, emergency room, and mortality register. The choice of data sources was based on the need to use the administrative databases more easily accessible and commonly used in the Italian regions.

In Italy, there are different regional experiences in using electronic health records, but so far no validation studies have been conducted in these regions. For example, in the Emilia‐Romagna region, algorithms were used based on six health records data (drug prescriptions, home care, hospital discharge, exemption from health‐care co‐payment, long‐term care facility, and mortality register), obtaining a 1‐year prevalence estimate similar to the prevalence estimate from international data (6.3% vs 7.6%). 22 , 27 In Canada, the adoption of a validated algorithm containing health administrative data with hospitalization, physician claim, and prescription filled in the primary care setting allows estimation of a prevalence of 7.2% cases of dementia in the population over 65 years. 8 Taking into account these experiences as well, we can assume that the definition of an algorithm that uses a larger number of administrative data in the context of primary care (with a representativeness of all forms of dementia at each stage of the disease), would better estimate the number of people with dementia in the general population.

To increase the accuracy, future and desirable research in this field should be conducted involving the expert centers for cognitive disorders so as to provide reliable diagnoses of dementia as also highlighted in an accurate systematic review on this topic in the UK. 28

In conclusion, we consider urgent promoting higher quality studies on the use of administrative data capable of intercepting cases with dementia in different countries. This will also allow the development of a “core set” of shared and validated epidemiological indicators on dementia to be collected routinely in the context of the WHO Global Dementia Observatory activities. 29

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Author disclosures are available in the supporting information.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Centers for Cognitive Disorders and Dementia (CCDD) teams and their attendants. The study was supported by grants from the Italian Ministry of Health—National Center for Disease Prevention and Control (2017).

Bacigalupo I, Lombardo FL, Bargagli AM, et al. Identification of dementia and MCI cases in health information systems: An Italian validation study. Alzheimer's Dement. 2022;8:e12327. 10.1002/trc2.12327

Ilaria Bacigalupo and Flavia L. Lombardo contributed equally to the work.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alzheimer's Disease International. 2019. World Alzheimer Report 2019: Attitudes to dementia. Alzheimer's Disease International. https://www.alzint.org/u/WorldAlzheimerReport2019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fleming R, Zeisel J, Bennett K. World Alzheimer Report 2020: Design Dignity Dementia: dementia‐related design and the built environment Volume 1. Alzheimer's Disease International; 2020. https://www.alzint.org/u/WorldAlzheimerReport2020Vol1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pot AM, Petrea I, Bupa/ADI report: Improving dementia care worldwide: Ideas and advice on developing and implementing a National Dementia Plan. Bupa/ADI, 2013. https://www.alzint.org/u/global‐dementia‐plan‐report‐ENGLISH.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4. Di Fiandra T, Canevelli M, Di Pucchio A, Vanacore N, Italian Dementia National Plan Working Group. The Italian Dementia National Plan. Commentary. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2015;51(4):261‐264. 10.4415/ANN_15_04_02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kosteniuk JG, Morgan DG, O'Connell ME, et al. Incidence and prevalence of dementia in linked administrative health data in Saskatchewan, Canada: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:73. 10.1186/s12877-015-0075-3. Published 2015 Jul 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ponjoan A, Garre‐Olmo J, Blanch J, et al. Epidemiology of dementia: prevalence and incidence estimates using validated electronic health records from primary care. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:217‐228. 10.2147/CLEP.S186590. Published 2019 Mar 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wilkinson T, Ly A, Schnier C, et al. Identifying dementia cases with routinely collected health data: a systematic review. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(8):1038‐1051. 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jaakkimainen RL, Bronskill SE, Tierney MC, et al. Identification of physician‐diagnosed Alzheimer's disease and related dementias in population‐based administrative data: a validation study using family physicians' electronic medical records. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;54(1):337‐349. 10.3233/JAD-160105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. DiFrancesco JC, Pina A, Giussani G, et al. Generation and validation of algorithms to identify subjects with dementia using administrative data. Neurol Sci. 2019;40(10):2155‐2161. 10.1007/s10072-019-03968-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Canevelli M, Di Pucchio A, Marzolini F, et al. A national survey of centers for cognitive disorders and Dementias in Italy. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;83(4):1849‐1857. 10.3233/JAD-210634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment‐beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med. 2004;256(3):240‐246. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging‐Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263‐269. 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, et al. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42(9):2672‐2713. 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182299496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51(6):1546‐1554. 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, et al. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011;134(Pt9):2456‐2477. 10.1093/brain/awr179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gorno‐Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011;76(11):1006‐1014. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821103e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017;89(1):88‐100. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Emre M, Aarsland D, Brown R, et al. Clinical diagnostic criteria for dementia associated with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2007;22(12):1689‐1837. 10.1002/mds.21507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Šimundić AM. Measures of diagnostic accuracy: basic definitions. EJIFCC. 2009;19(4):203‐211. Published 2009 Jan 20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chiari A, Vinceti G, Adani G, et al. Epidemiology of early onset dementia and its clinical presentations in the province of Modena, Italy. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17(1):81‐88. 10.1002/alz.12177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bacigalupo I, Mayer F, Lacorte E, et al. A systematic review and meta‐analysis on the prevalence of dementia in Europe: estimates from the highest‐quality studies adopting the DSM IV diagnostic criteria. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66(4):1471‐1481. 10.3233/JAD-180416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Benchimol EI, Manuel DG, To T, Griffiths AM, Rabeneck L, Guttmann A. Development and use of reporting guidelines for assessing the quality of validation studies of health administrative data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(8):821‐829. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cohen JF, Korevaar DA, Altman DG, et al. STARD 2015 guidelines for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies: explanation and elaboration. BMJ Open. 2016;6(11):e012799. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012799. Published 2016 Nov 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Amra S, O'Horo JC, Singh TD, et al. Derivation and validation of the automated search algorithms to identify cognitive impairment and dementia in electronic health records. J Crit Care. 2017;37:202‐205. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gallini A, Jegou D, Lapeyre‐Mestre M, et al. Development and validation of a model to identify Alzheimer's disease and related syndromes in administrative data. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2021;18(2):142‐156. 10.2174/1567205018666210416094639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fortuna D, Moro ML, Fabbo A, Epidemiologia della demenza in Emilia‐Romagna nel 2017 Analisi attraverso dati amministrativi. Servizio Sanitario Regionale – Emilia Romagna, 2018; 1‐30. https://assr.regione.emilia‐romagna.it/pubblicazioni/rapporti‐documenti/report‐demenza‐rer‐2017

- 28. McGuinness LA, Warren‐Gash C, Moorhouse LR, Thomas SL. The validity of dementia diagnoses in routinely collected electronic health records in the United Kingdom: a systematic review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2019;28(2):244‐255. 10.1002/pds.4669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. World Health Organization . Global status report on the public health response to dementia. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2021; 1‐137. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240033245 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Supporting Information

Supporting Information