Highlights

-

•

Indirect excess deaths in Peru were primarily caused by diseases of the circulatory system.

-

•

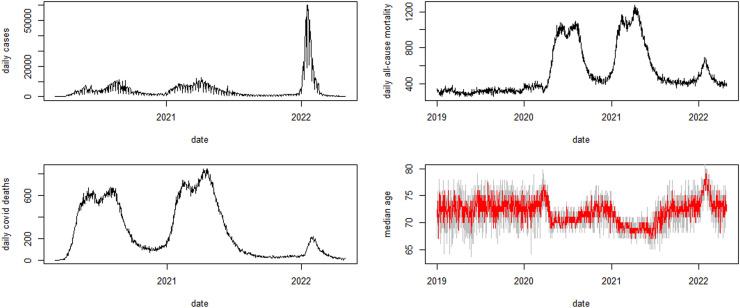

The median age at death was lower during the pandemic peak before the Omicron wave.

-

•

The median age at death increased to higher than normal during the peak of the Omicron wave.

Keywords: COVID-19, Median age, Excess mortality

Summary

There was heterogeneity in the median age of all-cause deaths in Peru during different waves of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Before predominance of the Omicron variant, the median age of deaths was lower than normal during the peaks of daily all-cause mortality. However, this increased above normal when the Omicron variant was predominant. The daily patterns of cause-specific deaths related directly and indirectly to COVID-19 in Peru were also investigated. Most excess deaths indirectly related to COVID-19 were caused primarily by diseases of the circulatory system, possibly due to disruption of medical services, and the majority of excess deaths directly related to COVID-19 were caused primarily by COVID-19 and diseases of the respiratory system.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2, the cause of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has spread all over the world, with approximately 5.7 million deaths and more than 384 million cases of infection by the end of 2021. Peru was one of the most affected countries in the COVID-19 pandemic, and had the highest numbers of confirmed cases, deaths per million population, and total excess deaths (Herrera‐Añazco et al., 2021).

Beaney et al. (2020) suggested that distinguishing between deaths that were directly and indirectly related to COVID-19 was crucial. Previous studies conducted in Peru explored the direct and indirect impacts of COVID-19 on the well-being of the population, and the quality and delivery of health care (Munayco et al., 2020; Taylor, 2021). However, there is limited research classifying direct and indirect COVID-19 deaths into specific causes of death.

Numerous studies have found that older age is strongly associated with death among patients with COVID-19 (Beaney et al., 2020; Dessie and Zewotir, 2021). In the USA, The New York Times reported that the older population had a higher mortality rate during the Omicron wave compared with previous waves (Mueller and Lutz, 2022). However, few studies have discussed the heterogeneity of age distribution of death during the pandemic in Peru.

As such, the authors used the death certificate dataset provided by the Peru Ministry of Health to extract daily all-cause mortality and median age of death from January 2019 to April 2022. This dataset lists every registered death with up to six descriptions of the cause of death. A death was considered to be related to COVID-19 if at least one of the six descriptions of the cause of death included ‘COV’. Cause-specific deaths were subgrouped based on the ICD-10 code of the primary cause of death. The daily count of cause-specific deaths in Peru was visualized in several disease groups, and compared with the daily number of cause-specific deaths not related to COVID-19 during the same period.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, there were two peaks of all-cause mortality before January 2022. During these two peaks, the median age of death was lower than normal, particularly during the second peak in the first half of 2021 (approximately) when the Lambda variant was predominant according to GISAID (Shu and McCauley, 2017). After January 2022, the Omicron variant predominated in Peru according to GISAID (Shu and McCauley, 2017). The peak of all-cause mortality during the Omicron wave was lower than the previous two peaks. However, the median age of death increased to approximately 77 years, compared with 71 and 69 years during the previous two peaks. One possible reason for this is that despite the lower fatality rate of the Omicron variant, the elderly population was more vulnerable to this variant than younger people.

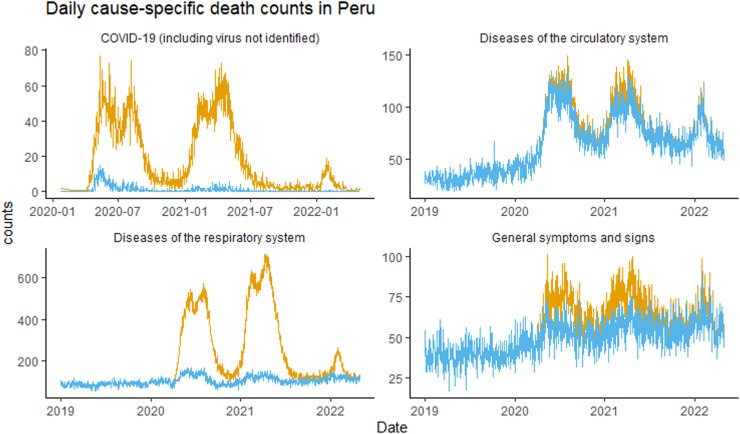

Three peaks in total mortality count were observed during the three waves of COVID-19. Compared with the pre-pandemic daily death count, excess deaths were mainly due to: diseases of the circulatory system (ICD-10 codes starting with I), diseases of the respiratory system (ICD-10 codes starting with J), general symptoms and signs (ICD-10 codes from R50 to R69), and COVID-19 (ICD-10 codes U71 and U72). Most excess deaths with ‘diseases of the respiratory system’ or ‘COVID-19’ (including virus not identified) registered as the primary cause of death were directly related to COVID-19, as the death registry mentioned ‘COV’ at least once in the description of the cause of death.

Most of the excess deaths indirectly related to COVID-19 had the primary cause of death registered as ‘diseases of the circulatory system’. During the first two waves of COVID-19, there was a peak of approximately 100 excess deaths each day due to diseases of the circulatory system. Among the indirect excess deaths caused by diseases of the circulatory system, most were due to acute myocardial infarction (42.8%), cardiac arrest (20.7%) and heart failure (7.9%). Similar results have been reported in Latvia (Gobiņa et al., 2022). This can be explained by the finding of the World Health Organization (2020) that services for cardiovascular emergencies were partially or completely disrupted in some countries during the pandemic. Furthermore, the prevalence of cardiovascular diseases in Peru before the pandemic was pronounced in the most urbanized regions, particularly on the coast (Chambergo-Michilot et. al., 2022), which corresponds with the areas hit hardest by the pandemic (Sempé et al., 2021); this may have increased the unmet demand for cardiovascular services. Another explanation is that COVID-19 is associated with a high inflammatory burden, which may lead to cardiovascular diseases (Madjid et al., 2020). Most of the excess deaths with ‘general symptoms and signs’ registered as the primary cause of death could be both directly and indirectly related to COVID-19 based on the descriptions of all causes of death.

In summary, this study reported the median age of death and the pattern of cause-specific mortality in Peru. In addition, this study determined excess deaths that were directly and indirectly related to COVID-19 during the three pandemic waves by investigating the descriptions of cause of death. It was found that, unlike the lower-than-normal median age of death during the first two waves of COVID-19, the median age of death was higher than normal when the Omicron variant was dominant in Peru. The majority of excess deaths directly related to COVID-19 had the primary cause of death registered as ‘COVID-19’ or ‘diseases of the respiratory system’, while most of the excess death indirectly caused by COVID-19 were primarily caused by ‘diseases of the circulatory system’; this may be a consequence of the disruption of medical services during the pandemic.

Figure 1.

Daily confirmed cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Peru (top left). Daily all-cause deaths (top right). Daily COVID-19 deaths (bottom left). Median age of all-cause deaths (in red), bootstrap 99% confidence interval (shaded area) in Peru (bottom right).

Figure 2.

Daily counts of four major groups of cause-specific mortality based on primary cause of death. Yellow lines show all registered deaths with cause of death information; blue lines exclude all registered deaths with ‘COV’ mentioned in at least one of the descriptions of the cause of death.

Funding

This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (HKU C7123-20G).

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval and individual consents were exempted as aggregated data were used in this study.

Availability of data and materials

All data used are from the public domain.

Author contributions

All authors conceived and conducted the research, wrote the draft, critically revised the manuscript, and approved the submission.

Conflict of interest

None declared. The funding agencies had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. Antonio M. Quispe for highlighting the link of the data.

References

- Beaney T, Clarke JM, Jain V, Golestaneh AK, Lyons G, Salman D, et al. Excess mortality: the gold standard in measuring the impact of COVID-19 worldwide? J R Soc Med. 2020;113:329–334. doi: 10.1177/0141076820956802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambergo-Michilot D, Atamari-Anahui N, Segura-Saldaña P, Brañez-Condorena A, Alva-Diaz C, Espinoza-Alva D. Trends and geographical variation in mortality from coronary disease in Peru. PLoS One. 2022;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0273949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessie ZG, Zewotir T. Mortality-related risk factors of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 42 studies and 423,117 patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:1–28. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06536-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobiņa I, Avotiņš A, Kojalo U, Strēle I, Pildava S, Villeruša A, et al. Excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in Latvia: a population-level analysis of all-cause and noncommunicable disease deaths in 2020. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13491-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Añazco P, Uyen-Cateriano A, Mezones-Holguin E, Taype-Rondan A, Mayta-Tristan P, Malaga G, et al. Some lessons that Peru did not learn before the second wave of COVID-19. Plann Manage. 2021;36:995–998. doi: 10.1002/hpm.3135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller B, Lutz E. During the Omicron wave, death rates soared for older people. The New York Times 31 May 2022.

- Madjid M, Safavi-Naeini P, Solomon SD, Vardeny O. Potential effects of coronaviruses on the cardiovascular system: a review. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:831–840. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munayco C, Chowell G, Tariq A, Undurraga EA, Mizumoto K. Risk of death by age and gender from COVID-19 in Peru, March–May, 2020. Aging. 2020;12:13869. doi: 10.18632/aging.103687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sempé L, Lloyd-Sherlock P, Martínez R, Ebrahim S, McKee M, Acosta E. Estimation of all-cause excess mortality by age-specific mortality patterns for countries with incomplete vital statistics: a population-based study of the case of Peru during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Region Health Americas. 2021;2 doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2021.100039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu Y, McCauley J.GISAID. Global initiative on sharing all influenza data – from vision to reality. Eurosurveillance. 2017;22:30494. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.13.30494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor L. COVID-19: why Peru suffers from one of the highest excess death rates in the world. BMJ. 2021;372:n611. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva: 2020. COVID-19 significantly impacts health services for noncommunicable diseases.https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/01-06-2020-covid-19-significantly-impacts-health-services-for-noncommunicable-diseases Available at. (accessed 9 November 2022) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data used are from the public domain.