Abstract

The behavioral and neural mechanisms by which distracters delay interval timing behavior are currently unclear. Distracters delay timing in a considerable dynamic range: Some distracters have no effect on timing ( “run”), while others seem to “stop” timing; some distracters re-start (“reset”) the entire timing mechanisms at their offset, while others seem to capture attentional resources long after their termination (“over-reset”). While the run-reset range of delays is accounted for by the Time-Sharing Hypothesis (Buhusi, 2012, 2003), the behavioral and neural mechanisms of “over-resetting” are currently uncertain. We investigated the role of novelty (novel / familiar) and significance (consequential / inconsequential) in the time-delaying effect of distracters, and the role of medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) catecholamines by local infusion of NDRI nomifensine, in a peak-interval procedure in rats. Results indicate differences in time-delay between groups suggesting a role for both novelty and significance: Inconsequential, familiar distracters “stopped” timing, novel distracters “reset” timing, while appetitively-conditioned distracters “over-reset” timing. mPFC infusion of nomifensine modulated attentional capture by appetitive distracters in a “U”-shaped fashion, reduced the delay after novel distracters, but had no effects after inconsequential, familiar distracters. These results were not due to nomifensine affecting either timing accuracy, precision, or peak response rate. Results may help elucidate the behavioral and physiological mechanisms underlying interval timing and attention to time, and may contribute to developing new treatment strategies for disorders of attention.

Keywords: peak-interval, timing, nomifensine, medial prefrontal cortex, attention, catecholamine

Associative and temporal learning are fundamental for behavioral control. Animals learn to predict appetitive and aversive environmental stimuli using information from both domains: They learn that some events are good predictors of particular outcomes, and that reward prediction is reliable within a particular time window. Flexibility in using associative and temporal landmarks is critical for adaptive response and survival (Buhusi & Meck, 2005; Gallistel, 1990; Gallistel & Gibbon, 2000; Kirkpatrick & Church, 1998). Also adaptive is the capability to filter out inconsequential stimuli (Lubow, 1989). Novel events increase arousal (Sokolov, 1960) and associability (Lubow, 1989), and produce disinhibition (Thompson & Spencer, 1966); presentation of novel events during a to-be-timed signal “resets“ (re-starts) timing (Buhusi & Matthews, 2014). Therefore, the capacity to pay attention to consequential events and filter out inconsequential intruders is critical for both proper associative and temporal processing. Previous studies investigated the role of intensity and discriminability of intruders (Buhusi, 2012), the effect of unexpected presentation of reinforcement (Matell & Meck, 1999), and the effect of repeated exposure to an intruder (Buhusi & Matthews, 2014) on the reset of an internal clock. In the present study we examined the role of intruder familiarity (familiar / novel) and intruder significance (consequential / inconsequential) on the reset of an internal clock, by evaluating the effect of these properties on the intruder’s subsequent time-disrupting properties.

To this end, one could examine the effect of interruptions (gaps) and distracters in a discrete-trial peak-interval (PI) procedure (Buhusi & Meck, 2000; Catania, 1970; Church, 1978). For example, during fixed-interval (FI) trials, the to-be-timed signal is turned on and the subjects’ first response after the criterion interval is reinforced and turns the to-be-timed signal off. During peak-interval (PI) trials, the to-be-timed signal is presented for a much longer duration than the criterion, but subjects’ responses are not reinforced. Trained subjects typically wait at the beginning of PI trials, then start responding and continue to respond throughout the trial, and quit responding towards the end of the trial: Therefore, in PI trials, the average rate of response gradually increases and peaks at the expected time of reward, then gradually decreases toward the end of the trial. In the PI procedure, the effect of interrupting events can be evaluated by presenting gaps (interruptions in the to-be-timed signal) during a PI trial, or by presenting distracters (cues not associated with timing) during the uninterrupted to-be-timed signal (Buhusi & Meck, 2000, 2006a, 2006b), and evaluating the delay in responding produced by these events. In this study we compared the effect of distracters previously paired with food with the effect of neutral, inconsequential (novel or familiar) distracters.

The effect of neutral intruders—gaps or distracters—on timing is currently best explained by the Time-Sharing Hypothesis, a theory developed (Buhusi, 2012, 2003; Buhusi & Meck, 2009) to explain two sets of findings. First, neutral distracters delay timing in a manner undistinguishable from gaps despite the presence of the timed stimulus (Buhusi & Meck, 2006a, 2006b). Second, both gaps and distracters delay timing anywhere on a continuum (Buhusi & Meck, 2006b; Buhusi, Paskalis, & Cerutti, 2006; Swearingen & Buhusi, 2010) between no delay (ignoring the distracter, “run”) (Buhusi, 2012; Buhusi et al., 2006), and a large delay (indicative of restarting timing after the intruder, “reset”) (Brodbeck, Hampton, & Cheng, 1998; Buhusi & Meck, 2006a; Buhusi et al., 2006; Buhusi, Sasaki, & Meck, 2002; Cabeza de Vaca, Brown, & Hemmes, 1994; Roberts, Cheng, & Cohen, 1989). The Time-Sharing Hypothesis (Buhusi, 2012, 2003; Buhusi & Meck, 2009) can be applied in the framework of the Scalar Expectancy Theory (Gibbon, 1977; Gibbon, Church, & Meck, 1984) as follows: Pulses regularly emitted by a pacemaker accumulate and are temporarily stored in working memory. During each FI trial, reinforcement is provided for the first response after the criterion interval, and the number of pulses currently in working memory is stored in reference memory. During PI trials, subjects use a ratio rule to compare currently accumulated time and the learned number of pulses associated with the time of reinforcement, so that the average response rate reaches a peak at the expected time of reinforcement. According to the Time-Sharing Hypothesis, during an interrupting event (gap and/or distracter), working memory for the interval preceding the interrupting event decays at a rate proportional to the salience of the interrupting event, due to memory and/or attentional resources being diverted toward processing the interrupting event (Buhusi, 2012, 2003; Buhusi & Meck, 2009). For example, if the salience of the intruder is relatively small, the delay is about equal to the duration of the distracter, as if the distracter “stops” timing (Church, 1978; Roberts, 1981); instead, salient intruders “reset” timing even if they are brief in duration (Buhusi & Meck, 2000). The theory is consistent with the human interval-timing literature (Fortin, 2003; Lejeune, 1998; Thomas & Weaver, 1975; Zakay, 1989, 2000).

While the vast majority of the experimental work supports the Time-Sharing Hypothesis, some experimental data cannot be accounted by it. First, the salience of a distracter, and its delaying effect should decrease with repeated presentations; in extremis, if exposed many times without consequences, the distracter should fail to attract attention, and should cease to delay timing, a prediction not confirmed experimentally (Buhusi & Matthews, 2014). Second, the Time-Sharing Hypothesis does not account for the effect of consequential distracters—e.g., paired with either appetitive or aversive reinforcers (Aum, Brown, & Hemmes, 2004; Brown, Richer, & Doyere, 2007; Matthews, He, Buhusi, & Buhusi, 2012), which delay timing beyond a “reset” (“over-reset”). Instead, a “postcue effect” was proposed to introduce an extra delay (Aum et al., 2004). Because post-distracter processes were not documented in previous studies using appetitive distracters (Aum et al., 2004; Matthews, Buhusi, & Buhusi, 2020), in this study we documented responding on both the timing- and distracter- (non-timing) levers, and evaluated whether the delay after distracters can be manipulated pharmacologically.

Timing is sensitive to a variety of pharmacological manipulations including catecholaminergic drugs (Buhusi & Meck, 2002; Cheng, MacDonald, & Meck, 2006; Lau, Ma, Foster, & Falk, 1999; Maricq, Roberts, & Church, 1981; Matell, Bateson, & Meck, 2006; Matell, King, & Meck, 2004; Matthews et al., 2012; Meck, 1983, 1996; Oprisan & Buhusi, 2011). Stimulants like methamphetamine and cocaine inhibit reuptake of catecholamines and have been shown to alter both timing (Maricq et al., 1981) and attention to time (Buhusi & Meck, 2002). Some catecholamine reuptake inhibitors, such as nomifensine (Katz, Guiard, El Mansari, & Blier, 2010), are effective antidepressants. For example, nomifensine has been shown to reduce immobility both in the forced swim test (Basso et al., 2005; Porsolt, Bertin, Blavet, Deniel, & Jalfre, 1979) and in the tail suspension test (Steru, Chermat, Thierry, & Simon, 1985), and was marketed as antidepressant in the 1970s and 1980s in the United States under the names Merital/Alival. Although the effects of some antidepressants on timing have been previously examined (Bayley, Bentley, & Dawson, 1998; Heilbronner & Meck, 2014; Ho et al., 1996; Matthews et al., 2012), here we aim at evaluating whether blockade of catecholamine reuptake in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) affects either (or both) timing and attention to time. The mPFC is thought to play an important role in timing (Buhusi, Reyes, Gathers, Oprisan, & Buhusi, 2018; Coull, Cheng, & Meck, 2011; Kim, Jung, Byun, Jo, & Jung, 2009; Meck, 2006; Merchant, Harrington, & Meck, 2013; Tucci, Buhusi, Gallistel, & Meck, 2014), as well as in other processes such as inhibitory control, working memory, and decision-making (Buhusi, Olsen, & Buhusi, 2017; Diamond, 2013; Euston, Gruber, & McNaughton, 2012), and, most importantly, in mediating top-down attentional control during a timing task (Buhusi et al., 2018; Matthews et al., 2012).

We expected the time delay after the distracter to vary with distracter’s novelty and significance, and to be modulated in a group- and dose-dependent manner by the blockade of catecholamine reuptake in mPFC (Matthews et al., 2012). We also evaluated whether blockade of catecholamine reuptake in mPFC interferes with responding on the timing- and distracter- (non-timing) levers before, during, and after the distracter.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Sprague Dawley rats (Harlan Laboratories, Inc., Indianapolis, IN), approximately 3 months old (300–350g) at the start of the experiment were used as subjects. Subjects (n=39) were randomly assigned to three groups at the beginning of the study: Familiar Appetitive (FA), Familiar Neutral (FN), and Novel Neutral (NN), and trained in procedures described below. Rats were maintained at about 85% of ad libitum weights by restricting food access within their home cages. Water was freely available in home cages. Experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with NIH’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and approved by Utah State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, protocols 2103/2254.

Apparatus

Behavioral procedures were conducted in 16 rat operant chambers housed in sound attenuating cubicles (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT), and equipped with two levers on either side of a pellet receptacle. For all rats, the left lever was the timing lever, and a 28-V 100-mA house light was used as a to-be-timed stimulus. FA rats were also reinforced for lever pressing on the right, non-timing lever, during the presentation of an 80-dB white noise stimulus, which was used as a distracter stimulus for all rats. Rats were reinforced with 45-mg pellets (Bio-Serv, Flemington, NJ).

Behavioral Procedures

Interval Timing.

Rats in all groups were trained as described in (Buhusi & Meck, 2006b): Rats were shaped to press on the timing (left) lever, and trained on a reversed fixed-interval (RFI)-40 schedule (Buhusi & Meck, 2000, 2006b), where the to-be-timed stimulus was the absence of the house light. During RFI trials, the first response on the timing lever 40 s into the trial resulted in food delivery and turned on the house light for the duration of the inter-trial interval (ITI). Afterwards, RFI trials were randomly intermixed with unreinforced reversed peak-interval (RPI) trials, during which the to-be-timed stimulus lasted three times the criterion time (120 s) irrespective of responding. Responding on the non-timing (right) lever during timing sessions was inconsequential. Trials were separated by variable 60 ± 30 s ITIs, during which the house light was illuminated.

Noise training.

In 12 separate sessions, Familiar Appetitive (FA) rats and Familiar Neutral (FN) rats were exposed to an 8-s noise to be used as distracter during testing, while Novel Neutral (NN) rats were not exposed to the noise until testing. During noise sessions, FA (but not FN) rats were reinforced for pressing on the non-timing (right) lever during the 8-s noise on a random-interval (RI)-8 schedule, with the probability of reward gradually reduced to 0.5.

Surgery

Under aseptic stereotaxic surgery, rats were implanted bilateral cannula guides (PlasticsOne, Roanoke, VA) aimed at medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) (AP: + 2.50 mm, ML: ± 0.60 mm, DV: −3.50 mm) (Paxinos & Watson, 1998). Rats were allowed to recover at least one week before behavioral testing resumed.

Drugs

Catecholamine reuptake blocker Nomifensine maleate (NOM) (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in vehicle: 45% methyl-beta-cyclodextrin (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in sterile saline. Drugs were prepared fresh prior to testing.

Local Infusions

Fifteen minutes before testing rats received 0.5 μL infusions of either NOM 0 ug, NOM 0.4 μg, or NOM 4 μg dissolved in vehicle, bilaterally into mPFC. Rats were tested in a Latin-square design to prevent testing biases. Infusions occurred at a rate of 0.25 μL/min for two minutes. Injector cannulae were left in place for two minutes following the infusion.

Interval-Timing Testing with and without Noise Distracters

Following drug infusion, rats were placed in operant boxes and randomly presented with RFI trials, RPI trials (test trials without distracters), and reversed peak-interval trials with noise distracter (RPI + N, test trials with distracters); for NN rats RPI + N trials were the first trials with a noise presentation. In RPI + N trials, the 8-s noise was presented 24 s into the trial. RPI + N trials were un-reinforced, response-independent probe trials lasting 120 s. Test sessions included about 55% RFI trials, 30% RPI trials, and 15% RPI+N trials, and lasted about 3 hours. FA and FN rats received noise re-training sessions in between drug testing sessions.

Histology

Rats were transcardially perfused with 10% formalin (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Brains were sectioned at 60 μm on a vibratome (VT 1200S, Leica) to estimate location of infusion.

Data Collection and Analysis

Both left (timing) and right (non-timing) lever presses, and rewards earned, were collected using MED-PC IV software (Med Associates, St Albans, VT). Timing responses in RPI and RPI + N trials in the testing phase were analyzed to determine timing accuracy (estimated peak time, thought to be an individual estimate of the criterion duration) and timing precision (width of the response function) using a curve-fitting method by which individual response curves were fit to a Gaussian (Buhusi & Meck, 2000; Swearingen & Buhusi, 2010), using the Marquardt–Levenberg algorithm (Marquardt, 1963) over an 80-s window of analysis: 0–80 s in RPI trials, and 32–112 s in RPI + N trials. After excluding rats with unreliable timing functions in any trial type during testing (r2 < 0.6), the estimated coefficient of determination was r2 = 0.88 ± 0.02 for FA rats, r2 = 0.87 ± 0.02 for FN rats, and r2 = 0.89 ± 0.01 for NN rats. An individual time delay in RPI + N trials relative to RPI trials was calculated as the difference between the estimated peak times in RPI + N and RPI trials. Non-timing responses in RPI + N trials in the testing phase were collected and analyzed in three 8-s time blocks: before, during, and after the distracter.

Exclusion Criteria

Rats that failed to acquire the timing and non-timing tasks (departing more than 20% off the criterion time, n=2; departing more than 3.5 SD off group average, n=2; failing to condition to the noise, n=1), and rats infused outside the region of interest (n=3), were eliminated from analyses. To prevent brain lesions, infusion sessions were limited to 1–2 per condition, which resulted in few test trials per condition (8–14); in turn, this reduced the “reliability” of the timing functions for some rats (functions were more noisy, variable), because obtaining stable timing response curves requires many test trials. Rats whose timing was deemed “unreliable” (whose timing accounted for less than 60% of the variability in their response curves, r2 < 0.6, n=8) were excluded from analyses. The number of rats used in analyses was: Familiar Appetitive (n=7), Familiar Neutral (n=7), Novel Neutral (n=9). The location of injection for these rats is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Injection location on coronal plates from (Paxinos & Watson, 1998).

Statistical Analyses

Estimated measures of peak time, time delay, timing precision, coefficients of determination (r2), and response rates on the timing and non-timing levers were analyzed using mixed ANOVAs with between-subjects variable group (FA, FN, NN) and within-subjects variables trial type (RPI, RPI + N) and NOM dose (0, 0.4, 4 μg). Based on previous studies in our lab (Matthews et al., 2020; Matthews et al., 2012), we hypothesized that groups would respond differentially to the distracter, and that NOM’s effect would vary by group and dose. Therefore, we followed the ANOVAs by planned comparisons and Fisher LSD post-hoc analyses. The alpha level for analyses was set at p = 0.05.

Transparency and openness

We report all data exclusions, all manipulations, and all measures in the study. All materials and animals are commercially available. Analyses were conducted using Statistica (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK). Data for this study are available by emailing the corresponding author. This study’s design and its analysis were not pre-registered.

Results

Familiar Appetitive Rats, But Not Familiar Neutral Rats, Conditioned To The Noise

In the last noise conditioning session FA rats earned 117.8 ± 20.9 rewards for pressing on the non-timing lever; the average rate of lever pressing during the 8-s noise was 8.5 ± 1.3 resp / min, indicating that FA rats conditioned to the noise. In contrast, FN rats which were exposed to the noise but were not reinforced, pressed the non-timing lever at a rate of 0.05 ± 0.02 resp / min, a rate significantly lower than that of FA rats (t(12)=12.87, p < 0.0001). These results indicate that FA rats conditioned to the noise and consistently earned rewards by pressing on the non-timing lever during the noise, while FN rats made few responses on the non-timing lever during the noise.

Timing Accuracy Was Not Affected By mPFC Infusion Of Nomifensine

Figure 2 shows normalized responding on the timing lever in trials without distracters (RPI, left panel) and trials with distracters (RPI + N, right panel). The left panel of Fig. 2 indicates that irrespective of group or drug dose the response functions in trials without distracters peaked about the criterion interval (40 s), suggesting that rats acquired the timing task, and that their timing accuracy was not affected by the drug regimen. Indeed, a mixed ANOVA of the estimated peak times in RPI trials with between-subjects variable group and within-subjects variable drug dose, failed to reveal any main effects or interactions (all Fs < 1.63, ps > 0.22). These results indicate that in peak trials without distracters the drug regimen did not affect timing accuracy irrespective of group or drug dose.

Figure 2.

Normalized timing functions under nomifensine (NOM) in trials without distracters (left panel) and trials with distracters (right panel). Distracter presentations are shown as black rectangles. Dotted vertical lines indicate the timing criterion (40 s, left panel) and the timing of a putative “reset” response after the distracter (right panel).

The Time Delay After Distracters is Affected by mPFC Infusion of Nomifensine in a Group- and Dose-Dependent Manner

The right panel of Figure 2 shows the normalized response functions on the timing lever in trials with distracters (RPI + N) by drug dose. The presentation of the distracter is indicated by a filled rectangle. The right panel of Fig. 2 shows the timing of a putative “reset” response (restarting timing after the distracter) as a vertical dotted line. Under vehicle FA rats “over-reset” (peak to the right of the reset line), NN rats “reset” (peak about the reset line), while FN rats “stop” timing during the noise (peak to the left of the reset line). The right panel of Figure 2 also indicates that in distracter trials the delay varied with the NOM dose in FA and NN rats, but not in FN rats.

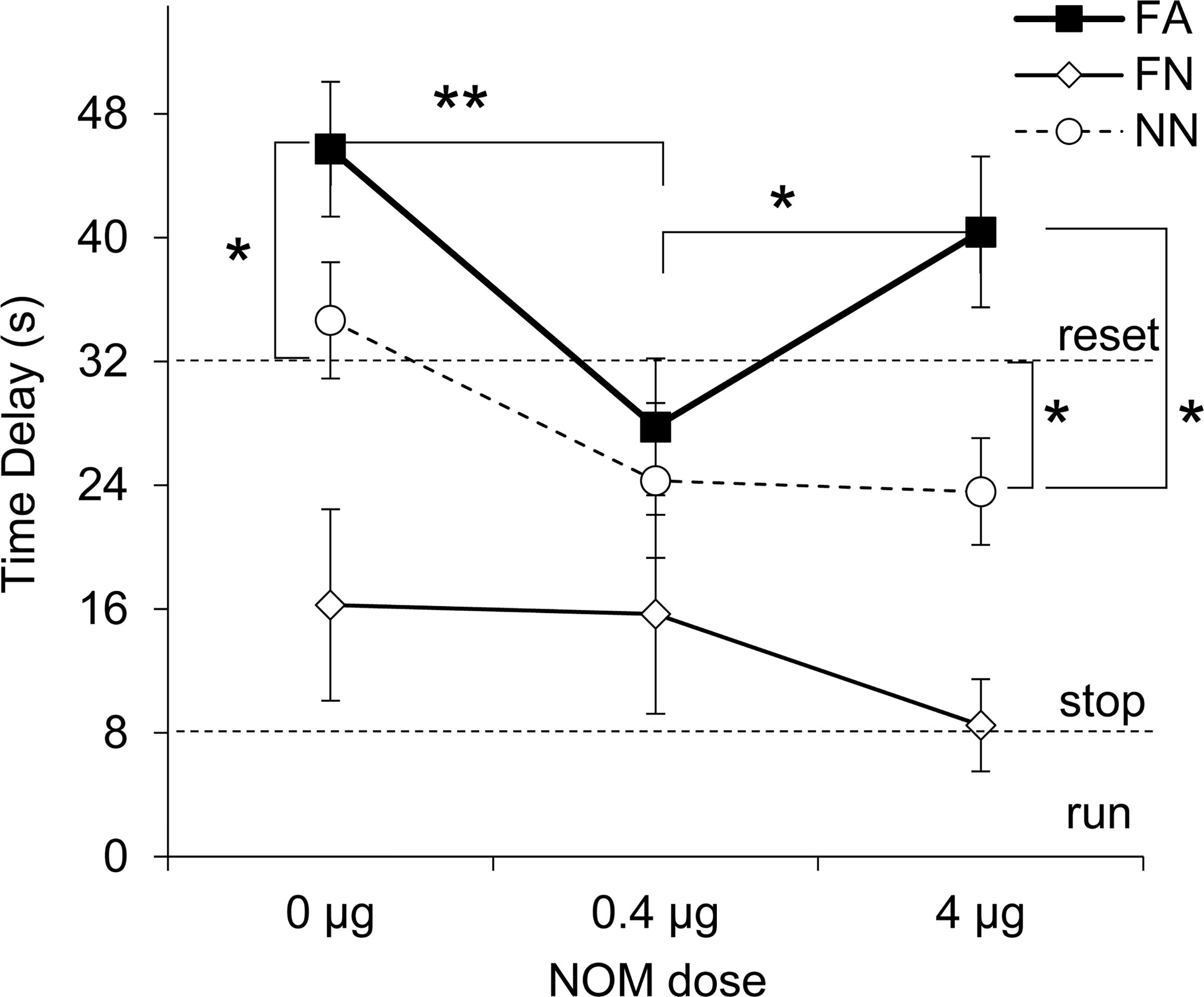

To evaluate the effect of the drug on timing after the distracter, a delay in peak time in RPI + N trials relative to RPI trials was computed by subtracting the estimated peak time in RPI trials from the estimated peak time in RPI + N trials, and shown in Fig. 3. Horizontal dotted lines indicate the timing of whether rats ignore the distracter (“run”, 0-s delay), “stop” their timing during the distracter (8-s delay), or re-start their timing after the delay (“reset”, 32-s delay). Figure 3 indicates large group differences, with FA and NN rats resetting or over-resetting, while FN rats seem to stop timing. Moreover, the drug seems to modulate the time delay in FA and NN groups in a dose-dependent manner, but not in FN rats. These suggestions were supported by statistical analyses detailed below.

Figure 3.

Average time delay (± SEM) under mPFC infusion of nomifensine (NOM). Dotted lines indicate behavioral responses “run” (0-s delay), “stop” (8-s delay), and “reset” (32-s delay). FA = Familiar Appetitive; FN = Familiar Neutral; NN = Novel Neutral; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

First, a mixed ANOVA of the estimated time delay in RPI+N trials relative to RPI trials with between-subjects variable group and within-subjects variable drug dose revealed a significant main effect of group (F(2,20) = 13.87, p = 0.0001, partial η2 = 0.58), indicating a very strong effect of novelty and / or significance. For example, under vehicle, a familiar, appetitive distracter delayed timing in the FA rats significantly more than a “reset” (32-s delay) (t(6) = 3.15, p = 0.019), while a familiar but neutral distracter only “stopped” timing (8-s delay) in FN rats (t(6) = 1.33, p = 0.231), suggesting that appetitive conditioning plays a large role in a distracter’s effect on timing. On the other hand, under vehicle, novel neutral distracters delayed timing considerably in NN rats, not significantly different from a “reset” (32-s delay) (t(8) = 0.71, p = 0.498), indicating that novelty also strongly contributes to the delaying effect of a distracter.

Second, analyses also revealed a significant, large main effect of drug dose (F(2,40) = 4.47, p = 0.017, partial η2 = 0.18), but no group x dose interaction (F(4,40) = 1.61, p = 0.189). LSD post-hoc analyses further indicated that the time delay varied with the NOM dose in FA and NN, but not in FN rats. FA rats delayed significantly less at the low NOM dose (not significant from a “reset”, t(6) = 0.958, p = 0.375), than both under vehicle (p = 0.0063) or the high dose (p = 0.0496); moreover, the delay at the 4 ug NOM dose was not significantly different than the delay at 0 ug dose, suggesting a “U”-shaped dose–response curve in FA rats. Similarly, while NN rats reset both under vehicle (t(8) = 0.709, p = 0.498) and low dose (t(8) = 1.539, p = 0.162), at the high dose their delay is significantly lower than a “reset” (t(8) = 2.44, p = 0.041). In contrast, FN rats “stop” at all NOM doses (ts < 1.33, ps > 0.231). In summary, analyses indicated a very strong effect of familiarity / significance of the distracter, and a strong effect of drug dose on the time delay after the distracter. Of further interest was to investigate differences in timing precision, peak rate of response, or responding on the timing and non-timing levers, and whether they account for the time delay differences noted above.

Timing Precision Was Not Affected By mPFC Infusion Of Nomifensine

While the right panel Fig. 2 may seem to indicate that timing precision (width of the response function) may affect by NOM infusion in trials with distracters (Fig. 2 right), this is likely an artifact of averaging timing functions varying in peak timing. Indeed, a mixed ANOVA of the individually estimated precision of timing in PRI and RPI+N trials with between-subjects variable group and within-subjects variable trial type and drug dose, failed to reveal any main effects or interactions with the drug dose (all Fs < 2.3, p > 0.073), indicating that precision was independent of drug manipulation, and does not account for the dynamics of time-delay differences under mPFC infusion of NOM.

The Peak Rate of Response On the Timing Lever Was Not Affected by mPFC Infusion of Nomifensine

A mixed ANOVA of the estimated peak rate of response on the timing lever with between-subjects variable group and within-subjects variables drug and trial type, failed to reveal any main effects or interactions with the drug dose (all Fs < 0.71, ps > 0.589), indicating that the peak rate of responding on the timing lever was independent of drug manipulation, and does not account for the dynamics of time delay differences under mPFC infusion of NOM.

Responding On The Timing Lever Was Decreased During and After Distracter Presentation In FA and NN Rats, But Not In FN Rats

While peak responding provides a global image of timing behavior, of particular importance for the dynamics of the time delay is responding around the time of distracter presentation. Figure 4 shows the rate of responding on the timing (left panel) and non-timing levers (right panel) in RPI + N trials in three 8-s time blocks: before the distracter (pre-distracter), during the distracter, and after the distracter (post-distracter). Figure 4 shows that pre-distracter, all groups responded robustly on the timing lever but not on the non-timing lever. A mixed ANOVA of pre-distracter response rate on the timing lever in RPI+N trials, with between-subjects variable group and within-subjects variables drug, failed to revealed any significant main effects or interactions (Fs < 2.03, ps > 0.108), suggesting that pre-distracter responding cannot differentiate between groups or drug doses.

Figure 4.

Response rate (± SEM) on the timing (left) and non-timing lever (right) in RPI+N trials under nomifensine in three 8-s time blocks: pre-distracter (8 s before the distracter), during the distracter, and post-distracter (8 s after the distracter). † significant differences between FA rats and both FN and NN rats (see text); †† significant differences between FN rats and both FA and NN rats (see text); * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

Instead, Fig. 4 shows that during and after the distracter, responding on the timing lever decreased in FA and NN rats (but not in FN rats). A mixed ANOVA of the response rate on the timing lever in RPI+N trials with between-subjects variable group and within-subjects variables drug and block revealed a significant, strong main effect of block (F(2,40) = 17.21, p = 0.0001, partial η2 = 0.46), and a strong block x group interaction (F(4,40) = 7.63, p = 0.0001, partial η2 = 0.43), suggesting that the robust responding before the distracter was followed by a significant reduction in responding in FA and NN rats, but not FN rats. Planned comparisons indicated lower rates of response during and after the distracter relative to pre-distracter levels in both FA (p = 0.0006) and NN rats (p = 0.0001), but not in FN rats (p = 0.4383). Planned comparisons also indicated that the rate of response was higher in FN rats relative to both FA and NN rats both during (p = 0.0205) and after the distracter (p = 0.0026). In summary, both FA and NN rats decreased their rate of response on the timing lever during and after the distracter (Fig. 4 left), and delayed timing considerably after the distracter (Fig. 3). In contrast, FN rats did not decrease their responding on the timing lever, and delayed their timing minimally (“stopped”) after the distracter (Fig. 3). Further support for differences between group and/or doses comes from analyses of the response rate on the non-timing lever.

mPFC Infusion of Nomifensine Decreased Responding On The Non-Timing Lever After Distracter’s Termination in FA Rats

Figure 4 also shows that while responding on the timing lever decreased, responding on the non-timing lever increased during the distracter and continued even after distracter’s offset in FA rats. Also, in these rats, NOM seemed to modulate responding on the non-timing lever, and to eliminate responding altogether after the distracter. These suggestions were supported by statistical analyses.

A mixed ANOVA of the response rates on the non-timing lever in RPI+N trials during and after the distracter, with between-subjects variable group and within-subjects variables drug and block revealed significant, very strong main effects of group (F(2,20) = 19.56, p = 0.0002, partial η2 = 0.66) and block (F(1,20) = 16.43, p = 0.0006, partial η2 = 0.45), and a significant, very strong group x block interaction (F(2,20) = 14.57, p = 0.0001, partial η2 = 0.59), driven by the higher response rate in FA rats, but not in FN and NN rats. Analyses also indicated a significant, large effect of drug (F(2,20) = 4.04, p = 0.025, partial η2 = 0.17), indicating that in FA rats the response rate decreased with an increase in NOM dose. Indeed, planned comparisons in FA rats indicated a lower response rate at the 4 μg dose than at the 0.4 μg dose both during (p = 0.0005) and post-distracter (p = 0.0064). Finally, analyses indicated a significant, large drug x block interaction (F(4,20) = 3.83, p = 0.009, partial η2 = 0.28), indicating that the drug effect also depended on the time block, with fewer responses post-distracter than during the distracter. Indeed, planned comparisons indicated that irrespective of dose, during the distracter FA rats responded significantly more than both FN and NN rats (all ps < 0.0007); however, post-distracter rats FA continued to respond more than FN and NN rats under vehicle (p = 0.0024) and at 0.4 μg NOM (p = 0.0141), but not at 4 μg NOM (p = 0.1443).

In summary, FA, but not FN or NN, rats responded on the non-timing lever during the distracter, as well as after its offset, which may explain the time delay results in Fig. 3. For example, FA rats responded on the non-timing lever after the distracter and were possibly delayed by the distracter beyond a “reset” by this post-distracter process (Fig. 3). Instead, even if NN rats were drastically affected by the distracter (Fig. 4 left) they were not delayed beyond a “reset” (Fig. 3), possibly because they did not engage in post-distracter behaviors (Fig.4 right). Finally, FN rats were minimally affected by the distracter both in their responding (Fig. 4 left) and timing (Fig. 3). In FA rats, NOM decreased responding on the non-timing lever post-distracter, and the 4 μg dose eliminated it altogether. Taken together, these results suggest that besides modulating attention to time (in NN rats), the drug decreased post-distracter responding (in FA rats).

Discussion

The present study investigated several hypotheses: The primary hypothesis is the Time-Sharing Hypothesis (Buhusi, 2012, 2003; Buhusi & Meck, 2009), that distracters presented during an interval timing task divert attentional resources away from timing in proportion to their salience (e.g., based on stimulus discrimination). With fewer resources at hand, timekeeping is delayed in the range “run” (no delay, ignoring the distracter) to “reset” (re-starting timing all over after the distracter) (Buhusi, 2012, 2003; Buhusi & Meck, 2009). Two sources of salience were evaluated in the present study: novelty (and its opposite: familiarity) (Buhusi, 2012; Buhusi & Matthews, 2014), and consequentionality (and its opposite: neutrality) of the distracter (Aum et al., 2004; Matthews et al., 2012). To this end, three groups of rats were presented with distracters with different significance: For the Familiar Appetitive (FA) rats the distracter was a familiar stimulus paired with food; for Familiar Neutral (FN) rats, the distracter was a familiar, neutral stimulus; for Novel Neutral (NN) rats, the distracter was a novel (unfamiliar), neutral stimulus to which these rats were not exposed until testing. By contrasting the effect of the distracter in FA and FN rats, one evaluates the role of consequentionality; by contrasting the effect of the distracter in NN and FN rats, one evaluates the role of familiarity / novelty. In our study, under vehicle, rats “stopped” timing after familiar (inconsequential) distracters (FN rats), but “reset” timing after novel (inconsequential) distracters (NN rats, Fig. 3), suggesting that novelty plays a role in the time-delaying effect of distracters.

A second hypothesis was that increased familiarity with an inconsequential distracter should prevent the distracter from engaging attentional resources, leading to rats to ignore the inconsequential distracter, and “run” through its presentation. While the time-delay in FN rats was significantly lower than in FA and NN rats, FN rats did not “run,” but rather “stopped” timing during the noise (Fig. 3), indicating that they noticed the distracter rather than ignore it, despite being extensively exposed to it. While there is strong evidence that the time delay produced by an interrupting event increases with discriminability (an element of novelty) (Buhusi, 2012; Buhusi et al., 2006; Buhusi, Perera, & Meck, 2005; Buhusi et al., 2002), only one experimental investigation of the relationship between time delay and the number of distracter presentations exists to date: In that study, inconsequential distracters retained their time-delaying properties despite extensive exposure (Buhusi & Matthews, 2014), a finding that parallels the fact that under specific experimental conditions repetition enhances rather than diminishes the salience of a stimulus (reviewed in Lubow, 1989). This interpretation is also supported by computer simulations showing that salience does not simply decrease with repetition but that it may also increase with it (under specific physiological conditions) (Buhusi, Gray, & Schmajuk, 1998).

While the delay in FN and NN rats can be accounted for by the Time-Sharing Hypothesis (Buhusi, 2012, 2003; Buhusi & Meck, 2009), the “over-reset” observed in FA rats under vehicle, cannot. Moreover, the current explanation for “over-resetting”, namely that some “post-distracter” processes further delay timing after distracter’s offset (Aum et al., 2004; Brown et al., 2007), is difficult to integrate in the Time-Sharing Hypothesis, because no such processes are posited by the latter. According to the Time-Sharing Hypothesis (Buhusi, 2012, 2003; Buhusi & Meck, 2009), it is not lever pressing on the non-timing lever after the distracter’s offset that delays timing in FA rats, but rather their lack the attentional resources dedicated to timing. According to the Time-Sharing Hypothesis, it is not engaging in “post-distracter” activities that delay timing (Aum et al., 2004; Brown et al., 2007), but the fact that such processes prevent attentional resources to be released and returned to timing, an interpretation that closely fits “attentional capture” phenomena in humans (Anderson, Laurent, & Yantis, 2013; Anderson & Yantis, 2013). As such, an “over-reset” may be due to the distracter not only being capable of diverting attentional resources away from timing, but also of capturing these resources, and preventing their release and return to timing even after the distracter’s termination, thus introducing and extra delay until timing mechanisms receive back these resources and use them accordingly. Indeed, while both FA and NN rats decrease their rate of response on the timing lever during and after the distracter (Fig. 4 left), only FA rats press on the non-timing lever during and, most importantly, after the termination of the distracter, indicating that they continue to engage attentional resources to activities other than timing at least 8 s post-distracter (Fig. 4 right). In FA rats, timing may have re-started only after “attentional capture” ceased and attentional resources were returned to timing (at least 8 s post-distracter), leading to more than 8-s delay beyond the “reset” (“over-reset”) (Fig. 3). In contrast, in NN rats, which do not engage in non-timing processes requiring their attentional resources (Fig. 4), attention may have returned to timing immediately after the distracter, such that they restarted timing at distracter’s offset (“reset”) (Fig. 3). Finally, even if FN rats were extensively exposed to the inconsequential distracter, its presentation may have still “captured” their attentional resources, and delayed their timing as if timing “stopped” during the distracter (Fig. 3). Thus, our study provides evidence for “attentional capture” of resources after both consequential and inconsequential distracters. The latter is important, as the “over-reset” of timing—which was thought to be restricted to consequential distracters (Aum et al., 2004; Brown et al., 2007; Matthews et al., 2020; Matthews et al., 2012)—was recently reported after neutral (but possibly, very salient distracters) (Buhusi, Bartlett, & Buhusi, 2017).

Taken together, our study provides evidence in favor of a Time-Sharing Theory by which timing is delayed when distracters divert attentional resources and possibly capture them for longer durations, depending on the distracter’s salience, such that timing does not resume (or re-start) until attentional resources are released and returned to timing, which can exceed considerably the distracter’s offset. As in previous versions of the Time-Sharing Hypothesis (Buhusi, 2012, 2003; Buhusi & Meck, 2009), these processes depend on the salience of the distracter: Low-salience distracters (e.g., low discriminability distracters, Buhusi, 2012) “capture” few attentional resources, and release them immediately, resulting in short delays in timing (“run” or “stop”); medium-salience distracters (novel, as in this study, or high discriminability distracters, as in Buhusi, 2012) “capture” more attentional resources but release them immediately, thus “resetting” timing; high-salience distracters (e.g., appetitive, as in this study, or inconsequential but highly-salient, as in Buhusi, Bartlett, et al., 2017) “capture” most attentional resources but release them relatively fast, thus exceeding “resetting” by short delays (Figs. 3 and 4), while highest-salience distracters (e.g., aversive, life-threatening distracters, as in Brown et al., 2007; Matthews et al., 2012) “capture” most attentional resources and release them very slow, long after their offset (Oprisan, Dix, & Buhusi, 2014). Because aversive distracters release attentional resources long after their offset, they delay timing considerably not only when presented during a timing trial (Matthews et al., 2012), but crucially, even when presented before a timing trial (Brown et al., 2007). This theoretical account provides the best explanation of the various manipulations to date.

The fourth hypothesis investigated in our study was that attentional resources necessary for timing depend on catecholamine levels in mPFC (Matthews et al., 2012). The present study evaluated whether increasing catecholamines in mPFC by blocking their reuptake through local infusion of Norepinephrine-Dopamine Reuptake Inhibitor (NDRI) nomifensine, alters the balance of attention devoted to either timing or the distracter, possibly by affecting “attentional capture”. To this end, rats were locally infused nomifensine (NOM) at 0, 0.4, and 4 μg dose before interval timing sessions in which they were tested both with trials with, and without, distracters. Analyses indicated that NOM infusion in mPFC reduced the time delay in FA and NN rats in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3), but not in FN rats, supporting the hypothesis that mPFC catecholamines are involved in the “brokerage” of attentional resources devoted to either timing or other distracter-specific processes. For example, under vehicle NN rats “reset” their timing, while at the 4 μg dose they delayed significantly less than “reset” (Fig. 3). Moreover, at the 4 μg dose, NOM eliminated “attentional capture” in FA rats (prevented FA rats from pressing on the non-timing lever past the end of the distracter, Fig. 4 right). Analyses also indicated that NOM effects on time delay are unlikely to be mediated by effects on timing accuracy, precision, or response peak rates. Taken together, these results suggest that blockade of catecholamine reuptake in mPFC may have a dual effect, both on increasing attentional resources devoted to time (e.g., as seen in NN rats), and in speeding-up the release and return of these resources back to timing (e.g., as seen in FA rats).

Interestingly, although NOM has been shown to increase dopamine (DA) accumulation in the frontal cortices, brain areas related to timing (Carboni, Imperato, Perezzani, & Di Chiara, 1989; Cass & Gerhardt, 1995; Kim et al., 2009), and although DAergic drugs are known to alter timing (Buhusi & Meck, 2005), we found no effect of NOM on timing accuracy in trials without distracters in either group (Fig. 2). These findings can be explained by the fact that although nomifensine acts as an indirect DA agonist, binding and blocking DAT and NET similar to amphetamine, it does not have amphetamine’s stimulatory effects on DA release (Hunt, Raynaud, Leven, & Schacht, 1979), as NOM does not reverse the DA pump direction (Hoffmann, 1982; Schacht & Heptner, 1974). Therefore, while amphetamine (Maricq & Church, 1983; Maricq et al., 1981; Meck, 1983) affects timing accuracy, NOM failed to show such an effect in the present study, and in previous studies in either rats (Matthews et al., 2012) or healthy human participants (Wittenborn, Flaherty, McGough, Bossange, & Nash, 1976).

When contrasting the results of the present study with those reported in a previous study in our lab in which rats were presented with aversive distracters while infused with NOM in mPFC (Matthews et al., 2012), it is interesting to note the following similarities regarding the effects of NOM PFC infusion: In both studies, NOM decreased the time-delay after the conditioned distracter. Also, in both studies NOM failed to affect the accuracy of timing in trials without distracters. Finally, in both studies NOM failed to affect timing after familiar neutral distracters, possibly because they may not engage attentional control circuits in PFC.

Also of interest is to compare and contrast current findings with those of another study in our lab (Matthews et al., 2020) in which rats were challenged with appetitively-conditioned or novel distracters while infused with NOM in mPFC, albeit notable differences in behavioral, neurophysiological, procedural, and control protocols. First, in both studies, under vehicle, rats delayed considerably after distracters. For example, in both studies rats “reset” timing after novel distracters. However, after appetitive distracters, rats “reset” timing in (Matthews et al., 2020) but “over-reset” in this study. This difference may be due to the position of the distracter in the trial (Aum et al., 2004), as well as to differences in the perceived salience (acquired through conditioning) of the appetitive distracter. For example, rats in the two studies could have differed in responding on the non-timing lever, which was not documented in Matthews et al. (2020). Second, in both studies NOM affected responding after appetitive distracters in a pattern compatible with a “U”-shaped dose-response curve. Most notably, in both studies, the 4 ug NOM dose seemed to increase the delay after appetitive distracters relative to the 0.4 ug dose; while these differences reached significance in this study, they did not in (Matthews et al., 2020), possibly due to differences in infusion location (see below) or differences in data quality / reliability. For example, this study used a more “conservative” threshold for data quality (higher r2). Third, the two studies reported somewhat different effects of NOM on the delay after novel distracters: While in both studies the 4 ug dose decreased the delay after novel distracters relative to the 0.4 ug dose, in Matthews et al. (2020) the delay at the 0.4 ug dose was also larger than the delay under vehicle. Differences between studies in the effect of NOM (at either dose) on the delay after distracters (either novel or appetitive, see previous point) may be due to differences in infusion location: In this study rats were infused in mPFC at large, while in Matthews et al. (2020) rats were infused specifically in the prelimbic sub-region of the PFC. Finally, it has been long recognized that catecholamines have a non-linear dose-response attentional effect—often described as “inverted-U” curve (Arnsten & Pliszka, 2011) —in mPFC. Depending on the “set point” of the subject on this “inverted-U” curve, catecholaminergic manipulations may result in either enhancement, or decrements, in attention. The two studies are fully compatible with this interpretation, where the effect of NOM to either decrease or increase attention may be modulated by the set point of the subject, possibly affected by multiple behavioral, physiological (e.g., infusion location), or procedural factors. More studies are necessary to understand attentional capture and its relationship to “over-resetting” timing, and to address similarities and discrepancies in this (relatively small) literature to date.

In summary, the present study documented the role of novelty (novel / familiar) and the role of significance (conditioned / neutral) in the time-delaying effect of distracters. It also showed that increasing catecholamines in mPFC by blocking their reuptake by an NDRI drug modulated attention to time depending on the group: Increasing catecholamines in mPFC sped-up the release and return of attentional resources to timing after consequential distracters (reduced “attentional capture”), increased resource allocation after novel distracters, but had little effect after familiar distracters. As in previous studies (Matthews et al., 2020; Matthews et al., 2012), increasing catecholamines in mPFC had no effect on timing accuracy, precision, or peak response rates. Results may help elucidate the behavioral and physiological mechanisms underlying interval timing and attention to time, and may contribute to developing new treatment strategies for disorders of attention. For example, the results of this study are compatible with a small clinical study where administration of nomifensine reduced attention deficits in participants with ADHD (Shekim, Masterson, Cantwell, Hanna, & McCracken, 1989).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants MH065561 and MH073057 to CB, and NS109723 to MB. The authors declare no competing interests. Data for this study are available by emailing the corresponding author.

References

- Anderson BA, Laurent PA, & Yantis S (2013). Reward predictions bias attentional selection. Front Hum Neurosci, 7, 262. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson BA, & Yantis S (2013). Persistence of value-driven attentional capture. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform, 39(1), 6–9. doi: 10.1037/a0030860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF, & Pliszka SR (2011). Catecholamine influences on prefrontal cortical function: relevance to treatment of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and related disorders. Pharmacol Biochem Behav, 99(2), 211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.01.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aum SW, Brown BL, & Hemmes NS (2004). The effects of concurrent task and gap events on peak time in the peak procedure. Behav Processes, 65(1), 43–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso AM, Gallagher KB, Bratcher NA, Brioni JD, Moreland RB, Hsieh GC, . . . Rueter LE (2005). Antidepressant-like effect of D(2/3) receptor-, but not D(4) receptor-activation in the rat forced swim test. Neuropsychopharmacology, 30(7), 1257–1268. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley PJ, Bentley GD, & Dawson GR (1998). The effects of selected antidepressant drugs on timing behaviour in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 136(2), 114–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodbeck DR, Hampton RR, & Cheng K (1998). Timing behaviour of blackcapped chickadees (Parus atricapillus). Behavioural Processes, 44, 183–195. doi: 10.1016/S0376-6357(98)00048-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BL, Richer P, & Doyere V (2007). The effect of an intruded event on peak-interval timing in rats: isolation of a postcue effect. Behav Processes, 74(3), 300–310. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2006.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV (2012). Time-sharing in rats: effect of distracter intensity and discriminability. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process, 38(1), 30–39. doi: 10.1037/a0026336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV (Ed.). (2003). Dopaminergic mechanisms of interval timing and attention. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV, Gray JA, & Schmajuk NA (1998). Perplexing effects of hippocampal lesions on latent inhibition: a neural network solution. Behav Neurosci, 112(2), 316–351. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.2.316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV, & Matthews AR (2014). Effect of distracter preexposure on the reset of an internal clock. Behav Processes, 101, 72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2013.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV, & Meck WH (2000). Timing for the absence of a stimulus: the gap paradigm reversed. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavioural Processes, 26(3), 305–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV, & Meck WH (2002). Differential effects of methamphetamine and haloperidol on the control of an internal clock. Behav Neurosci, 116(2), 291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV, & Meck WH (2005). What makes us tick? Functional and neural mechanisms of interval timing. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 6(10), 755–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV, & Meck WH (2006a). Interval timing with gaps and distracters: evaluation of the ambiguity, switch, and time-sharing hypotheses. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes, 32(3), 329–338. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.32.3.329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV, & Meck WH (2006b). Time sharing in rats: A peak-interval procedure with gaps and distracters. Behav Processes, 71(2–3), 107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2005.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV, & Meck WH (2009). Relative time sharing: new findings and an extension of the resource allocation model of temporal processing. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 364(1525), 1875–1885. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV, Paskalis JP, & Cerutti DT (2006). Time-sharing in pigeons: Independent effects of gap duration, position and discriminability from the timed signal. Behav Processes, 71(2–3), 116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2005.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV, Perera D, & Meck WH (2005). Memory for timing visual and auditory signals in albino and pigmented rats. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process, 31(1), 18–30. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.31.1.18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV, Reyes MB, Gathers CA, Oprisan SA, & Buhusi M (2018). Inactivation of the Medial-Prefrontal Cortex Impairs Interval Timing Precision, but Not Timing Accuracy or Scalar Timing in a Peak-Interval Procedure in Rats. Front Integr Neurosci, 12, 20. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2018.00020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi CV, Sasaki A, & Meck WH (2002). Temporal integration as a function of signal and gap intensity in rats (Rattus norvegicus) and pigeons (Columba livia). J Comp Psychol, 116(4), 381–390. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.116.4.381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi M, Bartlett MJ, & Buhusi CV (2017). Sex differences in interval timing and attention to time in C57Bl/6J mice. Behav Brain Res, 324, 96–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2017.02.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhusi M, Olsen K, & Buhusi CV (2017). Increased temporal discounting after chronic stress in CHL1-deficient mice is reversed by 5-HT2C agonist Ro 60–0175. Neuroscience, 357, 110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.05.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabeza de Vaca S, Brown BL, & Hemmes NS (1994). Internal clock and memory processes in animal timing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes, 20, 184–198. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.20.2.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carboni E, Imperato A, Perezzani L, & Di Chiara G (1989). Amphetamine, cocaine, phencyclidine and nomifensine increase extracellular dopamine concentrations preferentially in the nucleus accumbens of freely moving rats. Neuroscience, 28(3), 653–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cass WA, & Gerhardt GA (1995). In vivo assessment of dopamine uptake in rat medial prefrontal cortex: comparison with dorsal striatum and nucleus accumbens. J Neurochem, 65(1), 201–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania AC (1970). Reinforcement schedules and psychophysical judgements: A study of some temporal properties of behavior. In Schoenfeld WN (Ed.), The theory of reinforcement schedules (pp. 1–42). New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng RK, MacDonald CJ, & Meck WH (2006). Differential effects of cocaine and ketamine on time estimation: implications for neurobiological models of interval timing. Pharmacol Biochem Behav, 85(1), 114–122. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church RM (1978). The internal clock. In Hulse S, Fowler H & Honig W (Eds.), Cognitive processes in animal behavior (pp. 277–310). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Coull JT, Cheng RK, & Meck WH (2011). Neuroanatomical and neurochemical substrates of timing. Neuropsychopharmacology, 36(1), 3–25. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A (2013). Executive functions. Annu Rev Psychol, 64, 135–168. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euston DR, Gruber AJ, & McNaughton BL (2012). The role of medial prefrontal cortex in memory and decision making. Neuron, 76(6), 1057–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin C (2003). Attentional time-sharing in interval timing. In Meck WH (Ed.), Functional and neural mechanisms of interval timing (pp. 235–260). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gallistel CR (1990). The organization of behavior. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gallistel CR, & Gibbon J (2000). Time, rate, and conditioning. Psychol Rev, 107(2), 289–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon J (1977). Scalar expectancy theory and Weber’s law in animal timing. Psychological Review, 84(3), 279–325. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.3.279 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon J, Church RM, & Meck WH (1984). Scalar timing in memory. In Gibbon J & Allan LG (Eds.), Timing and time perception (Vol. 423, pp. 52–77). New York: The New York Academy of Sciences. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilbronner SR, & Meck WH (2014). Dissociations between interval timing and intertemporal choice following administration of fluoxetine, cocaine, or methamphetamine. Behav Processes, 101, 123–134. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2013.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho MY, al-Zahrani SS, Velazquez Martinez DN, Lopez Cabrera M, Bradshaw CM, & Szabadi E (1996). Effects of desipramine and fluvoxamine on timing behavior investigated with the fixed-interval peak procedure and the interval bisection task. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 125(3), 274–284. doi: 10.1007/BF02247339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann I (1982). Pharmacology of nomifensine. Int Pharmacopsychiatry, 17 Suppl 1, 4–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt P, Raynaud JP, Leven M, & Schacht U (1979). Dopamine uptake inhibitors and releasing agents differentiated by the use of synaptosomes and field-stimulated brain slices in vitro. Biochem Pharmacol, 28(13), 2011–2016. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(79)90217-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz NS, Guiard BP, El Mansari M, & Blier P (2010). Effects of acute and sustained administration of the catecholamine reuptake inhibitor nomifensine on the firing activity of monoaminergic neurons. J Psychopharmacol, 24(8), 1223–1235. doi: 10.1177/0269881109348178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Jung AH, Byun J, Jo S, & Jung MW (2009). Inactivation of medial prefrontal cortex impairs time interval discrimination in rats. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience, 3, 38. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.038.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick K, & Church RM (1998). Are separate theories of conditioning and timing necessary? Behavioural Processes, 44(2), 163–182. doi: 10.1016/S0376-6357(98)00047-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau CE, Ma F, Foster DM, & Falk JL (1999). Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling of the psychomotor stimulant effect of cocaine after intravenous administration: timing performance deficits. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 288(2), 535–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejeune H (1998). Switching or gating? The attentional challenge in cognitive models of psychological time. Behavioural Processes, 44, 127–145. doi: 10.1016/S0376-6357(98)00045-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubow RE (1989). Latent inhibition and conditioned attention theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maricq AV, & Church RM (1983). The differential effects of haloperidol and methamphetamine on time estimation in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 79(1), 10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maricq AV, Roberts S, & Church RM (1981). Methamphetamine and time estimation. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process, 7(1), 18–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt DW (1963). N algorithm for least-squares estimation of nonlinear parameters. Journal of the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 11(2), 11. [Google Scholar]

- Matell MS, Bateson M, & Meck WH (2006). Single-trials analyses demonstrate that increases in clock speed contribute to the methamphetamine-induced horizontal shifts in peak-interval timing functions. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 188(2), 201–212. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0489-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matell MS, King GR, & Meck WH (2004). Differential modulation of clock speed by the administration of intermittent versus continuous cocaine. Behav Neurosci, 118(1), 150–156. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.1.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matell MS, & Meck WH (1999). Reinforcement-induced within trial resetting of an internal clock. Behavioral Processes, 45, 157–171. doi: 10.1016/S0376-6357(99)00016-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews AR, Buhusi M, & Buhusi CV (2020). Blockade of Catecholamine Reuptake in the Prelimbic Cortex Decreases Top-down Attentional Control in Response to Novel, but Not Familiar Appetitive Distracters, within a Timing Paradigm. NeuroSci, 1(2), 99–114. doi: 10.3390/neurosci1020010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews AR, He OH, Buhusi M, & Buhusi CV (2012). Dissociation of the role of the prelimbic cortex in interval timing and resource allocation: beneficial effect of norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor nomifensine on anxiety-inducing distraction. Front Integr Neurosci, 6, 111. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2012.00111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meck WH (1983). Selective adjustment of the speed of internal clock and memory processes. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process, 9(2), 171–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meck WH (1996). Neuropharmacology of timing and time perception. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res, 3(3–4), 227–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meck WH (2006). Frontal cortex lesions eliminate the clock speed effect of dopaminergic drugs on interval timing. Brain Res, 1108(1), 157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.06.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant H, Harrington DL, & Meck WH (2013). Neural basis of the perception and estimation of time. Annu Rev Neurosci, 36, 313–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062012-170349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oprisan SA, & Buhusi CV (2011). Modeling pharmacological clock and memory patterns of interval timing in a striatal beat-frequency model with realistic, noisy neurons. Front Integr Neurosci, 5, 52. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2011.00052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oprisan SA, Dix S, & Buhusi CV (2014). Phase resetting and its implications for interval timing with intruders. Behav Processes, 101, 146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2013.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, & Watson C (Eds.). (1998). The rat brain (Forth ed.). San Diego, Ca: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Porsolt RD, Bertin A, Blavet N, Deniel M, & Jalfre M (1979). Immobility induced by forced swimming in rats: effects of agents which modify central catecholamine and serotonin activity. Eur J Pharmacol, 57(2–3), 201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S (1981). Isolation of an internal clock. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process, 7(3), 242–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts WA, Cheng K, & Cohen JS (1989). Timing light and tone signals in pigeons. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes, 15, 23–35. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.15.1.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schacht U, & Heptner W (1974). Effect of nomifensine (HOE 984), a new antidepressant, on uptake of noradrenaline and serotonin and on release of noradrenaline in rat brain synaptosomes. Biochem Pharmacol, 23(24), 3413–3422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shekim WO, Masterson A, Cantwell DP, Hanna GL, & McCracken JT (1989). Nomifensine maleate in adult attention deficit disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis, 177(5), 296–299. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198905000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolov EN (1960). Neuronal models and the orienting reflex. In Brazier MAB (Ed.), the central nervous system and behavior (pp. 187–276). New York: Macy Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Steru L, Chermat R, Thierry B, & Simon P (1985). The tail suspension test: a new method for screening antidepressants in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 85(3), 367–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swearingen JE, & Buhusi CV (2010). The pattern of responding in the peak-interval procedure with gaps: an individual-trials analysis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavioural Processes, 36(4), 443–455. doi: 10.1037/a0019485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas EAC, & Weaver WB (1975). Cognitive processing and time perception. Perception and Psychophysics, 17, 363–367. doi: 10.3758/BF03199347 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RF, & Spencer WA (1966). Habituation: a model phenomenon for the study of neuronal substrates of behavior. Psychological Review, 73(1), 16–43. doi: 10.1037/h0022681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucci V, Buhusi CV, Gallistel R, & Meck WH (2014). Towards an integrated understanding of the biology of timing. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 369(1637), 20120470. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittenborn JR, Flaherty CF Jr., McGough WE, Bossange KA, & Nash RJ (1976). A comparison of the effect of imipramine, nomifensine, and placebo on the psychomotor performance of normal males. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 51(1), 85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakay D (1989). Subjective time and attentional resource allocation: an integrated model of time estimation. In Levin I & Zakay D (Eds.), Time and human cognition: A life-span perspective (pp. 365–397). Amsterdam: Elesevier/North-Holland. [Google Scholar]

- Zakay D (2000). Gating or switching? Gating is a better model of prospective timing (a repsonse to ‘switching or gating?’ by Lejeune). Behavioural Processes, 50, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/S0376-6357(00)00141-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]