Abstract

Aim

There are no studies evaluating the long-term effects of antihypertensive medication on cognitive function and risk for impairment in a population with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) who have overweight or obesity. We aimed to determine whether antihypertensive medication (AHM) acting through the renin angiotensin system (RAS-AHM) compared to Other-AHM can mitigate these risks in people with T2DM.

Materials and Methods

This secondary analysis of the randomized controlled Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) study included 712 community-dwelling participants who were followed over 15 years. Logistic regression was used to relate RAS-AHM use to cognitive impairment, and linear regression was used to relate RAS-AHM use to domain-specific cognitive function after adjusting for potential confounders.

Results

563 reported RAS-AHM and 149 Other-AHM use during the study. RAS-AHM users have college or higher education (53%), higher baseline hemoglobin A1C (7.4), and reported higher diabetes medication use (86%), while Other-AHM users were more likely to be white (72%), obese (25%) and have cardiovascular history (19%). RAS-AHM use was not associated with a reduced risk of dementia compared to Other-AHM users. We did observe better executive function (Trail Making Test, part B, p<0.04), processing speed (Digit Symbol Substitution Test, p<0.004), verbal memory (Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test-delayed recall, p<0.005) and Composite score (p<0.008) among RAS-AHM users compared to Other-AHM users.

Conclusion

In this sample of adults with T2DM, free of dementia at baseline, we observed a slower decline in processing speed, executive function, verbal memory, and composite score among RAS-AHM users.

Keywords: antihypertensive medications, renin angiotensin system, dementia, cognitive impairment, cognitive decline, type 2 diabetes, overweight, obesity

1. INTRODUCTION

The recent Lancet Commission on dementia reported that ~40% of dementia cases are potentially preventable.1 Modifiable risk factors included physical activity, Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), obesity, and hypertension.1

T2DM has been associated with increased dementia risk.1,2. This risk is associated with T2DM duration3 and severity, based on T2DM complications;4 however, glycemic control has not been shown to alter dementia risk.5 T2DM has been associated with cognitive decline in memory, attention, processing speed, and executive function tests.6

There is evidence for the involvement of the renin angiotensin system (RAS) in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathogenesis,7–10 resulting in an increased interest in the effect of antihypertensive medication (AHM) acting via RAS, specifically angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) and angiotensin 1 receptor blockers (AT1RB), on AD risk. Several observational studies11–13 have shown a beneficial effect of these medications on AD. The Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory Study13 demonstrated that blood pressure control only partially mediated the beneficial effect, suggesting other mechanisms need to be explored. However, two recent meta-analyses14,15 found no evidence that the RAS-AHM class was more effective in dementia risk reduction than non-use or other AHM classes.14,15 It is important to note that most observational studies had a short follow-up, and only one studied the relationship between mid-life exposure and late-life dementia risk.

RAS plays a vital role in T2DM. Specifically, T2DM associated micro- and macrovascular complications are associated with overexpression of angiotensin II (ANGII) and overactivation of AT1R.16 Additionally, ANGII increases aldosterone production, impairing insulin signaling and worsening insulin resistance.16 Treatment with antihypertensive medication acting via the RAS system (RAS-AHM) (ACE-I, AT1RB) has been shown to improve glucose metabolism, delay insulin resistance, and prevent T2DM associated vascular complications in numerous clinical trials.16 However, only one study evaluated the effect of RAS-AHM on dementia risk in participants with T2DM and hypertension, which found that over a 12-year follow-up period, 2,377 ACE-I users had 26% lower all-cause dementia risk when compared to non-ACE-I users and that 1780 AT1RB users had 40% lower all-cause dementia risk when compared non-AT1RB users.17 There are currently no studies evaluating the effect of RAS-AHM on cognitive function in participants with T2DM.

The Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) trial evaluated the effect of intensive lifestyle modification on cardiovascular outcomes in people with T2DM and overweight or obesity at study entry18, and ancillary studies designed to determine whether these interventions influenced cognitive outcomes did not result in decreased risk of cognitive impairment19 or preserved cognitive function.20

Our study aimed to determine whether RAS-AHM use reduced the risk of cognitive impairment or slowed cognitive decline compared to other AHM use using the Look AHEAD study, which is suitable to evaluate our aims and interactions between lifestyle intervention and medication effect on cognitive outcomes.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Participants and Study Design

This study is a secondary analysis of cognitive data of the randomized controlled Look AHEAD trial. The Look AHEAD trial was a multicenter, single-blinded randomized controlled trial that recruited 5,145 individuals from 16 centers across the USA from 2001 to 2004 who were overweight or obese and T2DM.18 At enrollment, participants were 45–76 years of age with body mass index (BMI) 25 kg/m2 (≥27 kg/m2 if on insulin), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) <11%, systolic/diastolic blood pressure <160/<100 mmHg, triglycerides <600 mg/dl, and reported consuming ≤14 alcoholic drinks per week. Local Institutional Review Boards approved the protocols, and all participants provided written informed consent. Participants were randomly assigned with equal probability to a multidomain Intensive Lifestyle Intervention (ILI),21 which included frequent group or individual sessions focused on diet modification and physical activity designed to induce and maintain an average weight loss ≥7%, or a Diabetes Support and Education (DSE) control intervention,22 which consisted of group sessions featuring standardized protocols focused on improving diet, physical activity, and social support.23 Medical history and medications were assessed at initial and annual follow-up visits, and weight, height, and blood pressure were measured. The trial and both intervention arms were stopped in September 2012 after 9.6 years due to futility. Despite more weight loss and better glycemic control, there was no difference in the primary composite outcome of cardiovascular events between the ILI and DSE groups.23 The mean length of the intervention for participants was 9.8 years. The study continued as an observational cohort through 2021.

2.2. Variables

2.2.1. Exposure assessment

The Look AHEAD trial did not regulate medication management. Detailed information about medication use was collected at each visit by asking participants to bring in all prescribed medications, prescriptions, and over-the-counter medications. Our secondary analysis included medications that were coded into drug classes; for antihypertensive medications, this drug class consists of an angiotensin receptor 1 blocker (AT1RB) (candesartan, eprosartan, irbesartan, losartan, olmesartan, telmisartan, valsartan) or angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACE-I) (benazepril, captopril, enalapril, fosinopril, lisinopril, moexipril, perindopril, quinapril, ramipril, trandolapril) group. Since these medications act via the renin angiotensin system, they were grouped into the RAS-AHM group. We classified all other antihypertensive medication groups, including diuretics, beta receptor blockers, calcium channel blockers, and alpha 1 receptor blockers, in a group of other antihypertensive medication users (Other-AHM). Participants were assigned to the RAS-AHM group if they reported RAS-AHM use at any visit but not Other-AHM use. Similarly, participants were assigned to the Other-AHM group if they reported Other-AHM use at any visit but not RAS-AHM use. Participants who used both types of AHMs, concurrently or at different visits were excluded from this analysis.

ACE-I and AT1RB were further divided into those that cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB-C) (captopril, fosinopril, lisinopril, perindopril, ramipril, trandolapril, candesartan, telmisartan, valsartan) and those that do not cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB-NC) (benazepril, enalapril, moexipril, quinapril, eprosartan, irbesartan, losartan, olmesartan). This classification was used to address findings from previous studies and a recent meta-analysis24 that the use of blood-brain barrier crossing RAS-AHM in cognitively normal older adults decreased the rate of cognitive decline. The classification was primarily based on reviews of the literature and medication package inserts.

We, however, did not further divide RAS-AHM and Other-AHM users by intervention, DSE vs. ILE.

2.2.2. Outcome: Cognitive assessment and dementia diagnosis

Cognitive assessments were conducted between August 2009 and February 2020 in various ancillary studies, Look AHEAD Physical and Cognitive Function (August 2009 – June 2012, N=977), Look AHEAD M&M/Brain (Nov 2011–Aug 2013, N=601), and Look AHEAD-C (August 2013 – December 2014, N=3,075). The same cognitive protocol was applied in the Look AHEAD-MIND (May 2018–Feb 2020, N=2,451), allowing for a total of 4 possible cognitive assessments at years 8–9, 10–11, 12–14, and 15–18 from randomization.

The cognitive testing included the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) to assess verbal learning and memory,25 Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST) to assess attention and processing speed,26 the Modified Stroop Color and Word Test (Stroop) to assess interference,27 and the Trail Making Test Parts A and B (TMT, Part A and B) to assess attention, processing speed and executive function, respectively.28 The Modified Mini Mental Status Exam (3MSE)29 assessed global cognitive function.

When a participant scored below the pre-specified age and education-specific cut point, it triggered the administration of the Functional Assessment Questionnaire (FAQ)30 to a friend or family member previously identified by the participant to assess functional status and performance on instrumental activities of daily living to help identify cognitive impairment. Two masked adjudicators independently reviewed all Look AHEAD cognitive test and depression scores, FAQ, and medical and health information to classify participants as not impaired, having mild cognitive impairment (MCI),31, or with probable dementia.19,32 Due to the relatively small number of dementia cases, we have developed a group called “cognitive impaired” where participants diagnosed with MCI (N=34, 4.8 %) or probable dementia (N=13, 1.8%) were grouped.

2.2.3. Covariates

Based on previous literature, we assessed baseline covariates possibly related to T2DM, antihypertensive medication use, or dementia. These included baseline: age, sex, race, education (high school or less, college graduate, post-college), body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) (≥25 – < 30, ≥30 – < 40, ≥40), smoking status (never, past, present), alcohol consumptions status (none/week, 1–3/week, 4+/week), hemoglobin A1c (HgbA1C %) (< 7.0, 7.0–8.9, >9.0), mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP, DBP) throughout the study, serum creatinine, history of hypertension, apolipoprotein ε4 (APOE) genotype (no ε4, one ε4, two ε4 alleles), Beck Depression Index (0–10, ≥11) and history of cardiovascular disease (CVD). History of CVD included self-report of myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass graft, carotid endarterectomy, lower leg angioplasty, aortic aneurysm, congestive heart failure, or history of stroke. APOE ε4 carrier status was determined for participants who provided consent (80% of women versus 86% of men, p<0.001) using TaqMan genotyping (rs7412 and rs429358). We also included the study site and intervention.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Participants who completed a cognitive evaluation and reported AHM use were eligible for inclusion. The sample was defined by having an adjudicated cognitive status; thus, they were all alive and had not been lost to follow-up. All contributed to the analysis, except for the analysis for risk for cognitive impairment participants were censored when they were diagnosed with MCI or dementia.

The clinical trial concluded in 2012, but cognitive assessments occurred in four ancillary observational studies using identical protocols between 2009 – 2020: counting from the original randomization during years 8–9, 10–11, 12–14, and 15–18, providing us with four time points.

Participant characteristics were compared using t-tests and ANOVA for continuous variables and Chi-squared tests for categorical variables for included vs. excluded participants. We identified potential confounders significantly related to AHM use at a significance of p≤0.05 and included them in the analyses. Analyses were adjusted for baseline age, sex, education, race/ethnicity, intervention, BMI, SBP, hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C), use of any diabetes medication, and CVD.

After adjusting for potential confounders, logistic regression was used to relate RAS-AHM to cognitive impairment. Repeated measures of linear regression to account for within-subject correlation was used to evaluate associations between RAS-AHM and cognitive function after adjusting for potential confounders. We also explored the effect of RAS-AHM based on the medication type (ACE-I) and blood-brain barrier crossing status on dementia risk (using logistic regression analysis) and cognitive function (using the repeated measures linear regression model). To evaluate the potential role of intervention and SBP on the effect of AHM on cognitive impairment, we have added an interaction term between AHM use and intervention arm; and AHM use SBP to the fully adjusted model.

Cognitive function test scores were treated as continuous variables and were standardized (z-scores) by subtracting scores from the overall cohort-wide mean of the initial assessments and dividing this by their standard deviation (SD).33 Domain-specific scores were formed by taking the average z-scores for tests in each domain. The primary cognitive measure used in the Look AHEAD studies is a composite of the average of these domain scores.34

All analyses were done in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for Windows.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participants

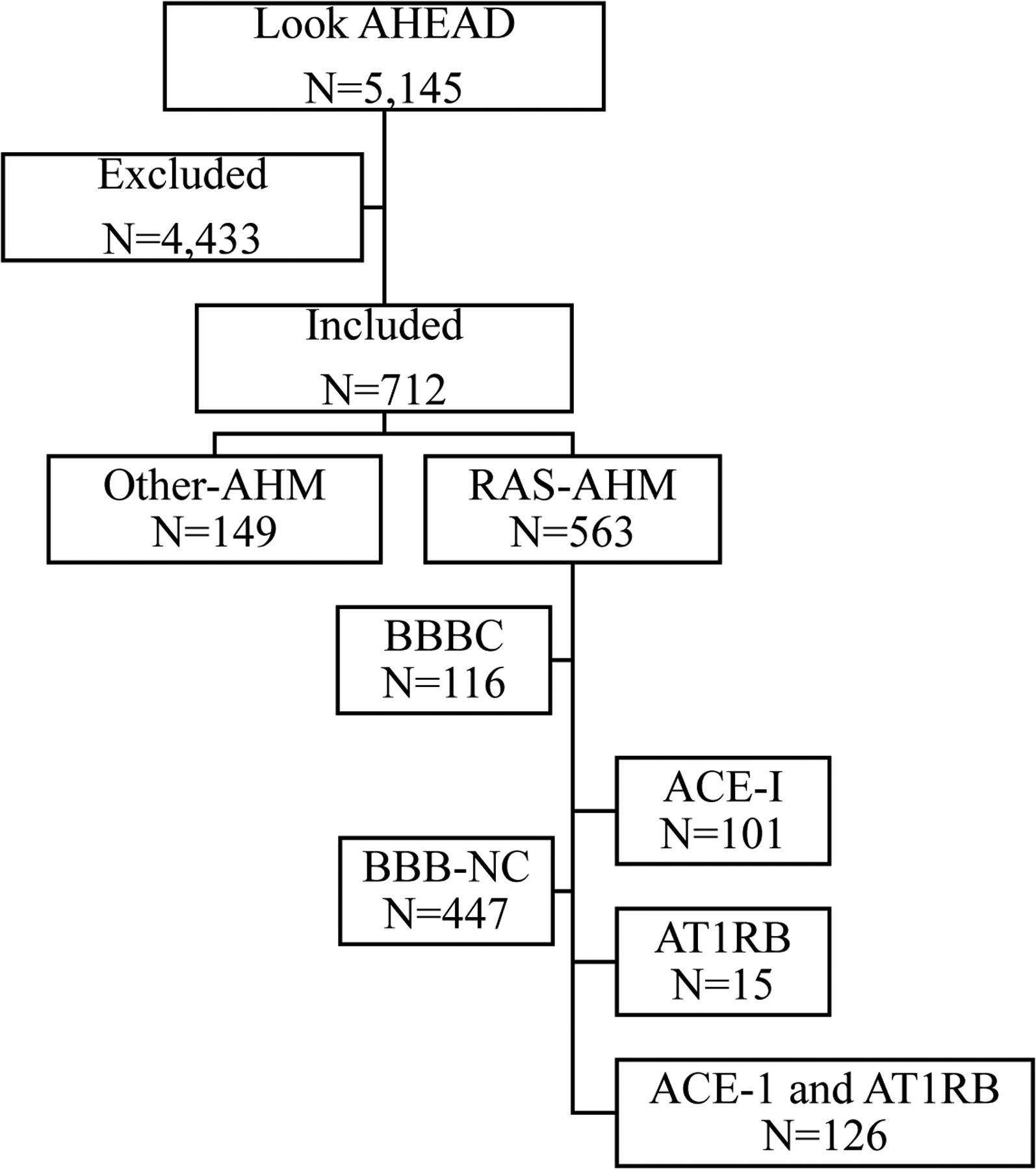

The analysis included 712 participants with an adjudicated cognitive status who used either RAS-AHM (N=563) or Other-AHM (N=149) (Figure 1). RAS-AHM users were more likely to have college or higher education (53%), higher baseline hemoglobin A1C (7.4), and higher diabetes medication use (86%), while Other-AHM users were more likely to be white (72%), obese (25%) and have a history of CVD (19%) (Table 1). The racial difference could be due to guidelines since RAS-AHM have been less effective in African American population; thus, they may be less often prescribed.35 The difference in CVD disease could be explained in guidelines for using beta-blockers assigned to Other-AHM in CVD.

Figure 1. Flow of participants.

Excluded: no cognitive exam or no reported antihypertensive medication (AHM) use or AHM groups were switched during the span of the study.

Included: All four cognitive evaluations and reported use of AHM with no switch of AHM group during the span of the study.

RAS-AHM (antihypertensive medications acting via the renin angiotensin system) included: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) and angiotensin 1 receptor blockers (AT1RB).

Other-AHM included: diuretics, beta receptor blockers, calcium channel blockers, and alpha 1 receptor blockers.

Blood-brain barrier crossing (BBB-C) and non-crossing (BBB-NC)

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants with cognitive assessments (RAS-AHM compared to Other-AHM)

| Overall N=712 (N [%]) |

RAS-AHM# N=563 (N [%]) |

Other-AHM## N=149 (N [%]) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention Assignment | 0.43 | |||

| DSE | 1064 (49.9) | 558 (50.9) | 506 (48.8) | |

| ILI | 1069 (50.1) | 539 (49.1) | 530 (51.2) | |

| Age (years) | <0.001 | |||

| 45–54 | 245 (34.4) | 210 (37.3) | 35 (23.5) | |

| 55–64 | 370 (52.0) | 294 (52.2) | 76 (51.0) | |

| 65–76 | 97 (13.6) | 59 (10.5) | 38 (25.5) | |

| Gender | 0.40 | |||

| Male | 256 (36.0) | 198 (35.2) | 58 (38.9) | |

| Female | 456 (64.0) | 365 (64.8) | 91 (61.1) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | <0.001 | |||

| African-American | 72 (10.1) | 50 (8.9) | 22 (14.8) | |

| American Indian | 72 (10.1) | 65 (11.6) | 7 (4.7) | |

| Hispanic | 97 (13.6) | 89 (15.8) | 8 (5.4) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 456 (64.0) | 349 (62.0) | 107 (71.8) | |

| Other | 15 (2.1) | 10 (1.8) | 5 (3.4) | |

| Education | 0.79 | |||

| High School or less | 324 (46.4) | 258 (46.6) | 66 (45.8) | |

| College Graduate | 242 (34.7) | 189 (34.1) | 53 (36.8) | |

| Post College | 132 (18.9) | 107 (19.3) | 25 (17.4) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.80 | |||

| ≥25 - < 30 | 141 (19.8) | 113 (20.1) | 28 (18.8) | |

| ≥30 - < 40 | 436 (61.2) | 346 (61.5) | 90 (60.4) | |

| ≥40 | 135 (19.0) | 104 (18.5) | 31 (20.8) | |

| Mean (SD) | 34.9 (5.7) | 34.8 (5.7) | 35.3 (5.9) | 0.31 |

| HbA1c (%) | 0.08 | |||

| <7.0 | 301 (42.3) | 245 (43.5) | 56 (37.6) | |

| 7.0–8.9 | 352 (49.4) | 267 (47.4) | 85 (57.1) | |

| ≥9.0 | 59 (8.3) | 51 (9.1) | 8 (5.4) | |

| Mean (SD) | 7.19 (1.14) | 7.24 (1.17) | 7.00 (0.99) | 0.01 |

| Blood Pressure (mmHg)* | ||||

| SBP†

(systolic blood pressure) |

124.4 (14.9) | 124.1 (14.8) | 125.2 (15.1) | 0.45 |

| DBP†

(diastolic blood pressure) |

69.6 (9.1) | 69.7 (9.2) | 69.5 (8.7) | 0.88 |

| History of CVD‡ (% yes) | 50 (7.0) | 25 (4.4) | 25 (16.8) | 0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia (% yes) | 453 (63.6) | 352 (62.5) | 101 (67.8) | 0.24 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 193.9 (38.0) | 193.8 (37.6) | 194.4 (39.5) | 0.86 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 44.0 (12.4) | 43.8 (12.4) | 44.7 (12.2) | 0.42 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 114.0 (32.2) | 113.8 (31.8) | 114.7 (33.9) | 0.76 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 185.2 (126.8) | 185.6 (124.9) | 183.8 (134.4) | 0.88 |

| Kidney Disease (% yes) | 43 (6.0) | 32 (5.7) | 11 (7.4) | 0.44 |

| Serum Creatinine (mg/dL)† | 0.78 (0.18) | 0.78 (0.18) | 0.81 (0.17) | 0.05 |

| Smoking Status | 0.23 | |||

| Never | 1072 (50.3) | 555 (50.7) | 517 (50.0) | |

| Past | 977 (45.9) | 499 (45.6) | 478 (46.2) | |

| Present | 81 (3.8) | 41 (3.7) | 40 (3.9) | |

| Alcohol Intake | 0.74 | |||

| None/week | 1458 (68.5) | 724 (66.2) | 734 (71.0) | |

| 1–3/week | 427 (20.1) | 229 (20.9) | 198 (19.2) | |

| 4+/week | 243 (11.4) | 141 (12.9) | 102 (9.9) | |

| APOE carrier status | 0.20 | |||

| No e4 alleles | 438 (77.7) | 344 (79.1) | 94 (72.9) | |

| 1 e4 allele | 110 (19.5) | 81 (18.6) | 29 (22.5) | |

| 2 e4 alleles | 16 (2.8) | 10 (2.3) | 6 (4.7) | |

| Beck Depression Index (BDI) | 0.44 | |||

| 0–10 | 549 (85.5) | 429 (85.0) | 120 (87.6) | |

| ≥11 | 93 (14.5) | 76 (15.0) | 17 (12.4) | |

| Cognitive Status | 0.05 | |||

| Normal | 665 (93.4) | 531 (94.3) | 134 (89.9) | |

| MCI (mild cognitive impairment) |

34 (4.8) | 35 (4.4) | 9 (6.0) | |

| Dementia | 13 (1.8) | 7 (1.2) | 6 (4.0) | |

| Diabetes medication | ||||

| Any medication | 596 (85.0) | 482 (86.5) | 114 (79.2) | 0.03 |

| Insulin | 74 (10.8) | 59 (10.8) | 15 (11.0) | 0.95 |

| Biguanides | 422 (60.8) | 341 (61.8) | 81 (57.0) | 0.30 |

Renin Angiotensin System-antihypertensive medications (RAS-AHM)

Other-antihypertensive medications (Other-AHM)

Cardiovascular disease (CVD)

Mean (SD)

Forty-seven participants developed cognitive impairment (mild cognitive impairment N=34 [4.8%] or dementia N=13 1.8%]) during an average of 14.8 years of follow-up (Table 1). The cognitive characteristics from the first measured visit [means (SD)] 3MSE, TMT part A and part B times (sec), Stroop, DSST, RAVLT delayed, and composite scores were indicative of a high functioning sample (Table 2). RAS-AHM users performed significantly better at the first visit on TMT part B, DSST, RAVLT delayed, and composite score (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cognitive characteristics from the first visit with cognitive measures

| Overall N=712 (Mean [SD]) |

RAS-AHM N=563 (Mean [SD]) |

Other-AHM N=149 (Mean [SD]) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3MSE | 91.8 (6.8) | 91.9 (6.9) | 91.3 (6.3) | 0.34 |

| TMT, part A | 37.3 (20.3) | 36.6 (20.8) | 40.2 (18.0) | 0.07 |

| TMT, part B | 106.6 (68.5) | 102.3 (66.8) | 123.4 (72.9) | 0.002 |

| Stroop | 32.3 (15.6) | 31.8 (15.0) | 34.2 (17.4) | 0.12 |

| DSST | 41.5 (10.7) | 42.3 (10.8) | 38.4 (9.7) | <0.001 |

| RAVLT delayed | 41.4 (9.5) | 42.0 (9.4) | 39.0 (9.9) | 0.002 |

| Composite z-score | −0.037 (0.79) | 0.009 (0.78) | −0.220 (0.78) | 0.003 |

3MSE (Modified Mini Mental Status Exam)

TMT, part A, and B (Trail Making Test Parts A and B)

Stroop (Modified Stroop Color and Word Test)

DSST (Digit Symbol Substitution Test)

RAVLT (Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test)

3.2. Association between RAS-AHM use and cognitive impairment

Among the RAS-AHM users, 7.5% were diagnosed with either MCI or dementia (cognitive impairment), while of the Other-AHM users, 10.1% were diagnosed with MCI or dementia (cognitive impairment) (Table 1). In the fully adjusted model, there was no significant risk reduction for cognitive impairment among RAS-AHM users compared to Other-AHM users (OR=0.62, 95% CI 0.29–1.31; p=0.21) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic regression results: Association between type of AHM use and cognitive impairment

| Cognitive Impairment (MCI or Dementia) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted for Demographics^ | Adjusted for Demographics and Health characteristics^^ | ||||

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| RAS-AHM vs Other-AHM | 0.54 (0.28 – 1.02) |

0.06 | 0.73 (0.36 – 1.50) |

0.39 | 0.62 (0.29 – 1.31) |

0.21 |

| ACE-I vs Other-AHM | 0.27 (0.08 – 0.97) |

0.04 | 0.36 (0.10 – 1.35) |

0.13 | 0.30 (0.07 – 1.25) |

0.10 |

| #BBB-C vs ##BBB-NC | 0.53 (0.18 – 1.56) |

0.10 | 0.54 (0.18 – 1.63) |

0.40 | 0.57 (0.19 – 1.76) |

0.30 |

| BBB-C vs Other AHM | 0.32 (0.10 – 0.99) |

0.44 (0.13 – 1.45) |

0.39 (0.11 – 1.34) |

|||

| BBB-NC vs Other AHM | 0.60 (0.31 – 1.15) |

0.80 (0.39 – 1.66) |

0.67 (0.32 – 1.43) |

|||

BBB-C (Blood-brain barrier crossing)

BBB-NC (Blood-brain barrier non-crossing)

Adjusted for baseline age, sex, education, and race/ethnicity

Adjusted for baseline age, sex, education, race/ethnicity, study intervention, BMI, SBP, HgbA1C, use of diabetes medication, CVD

One-hundred-one participants reported ACE-I and 15 participants AT1RB use. In the unadjusted model, there was a significant 73% lower risk of cognitive impairment among ACE-I users compared to Other-AHM users (OR=0.27, 95% CI 0.08–0.97; p=0.04); however, after adjusting potential confounders, this differential in risk was no longer significant (OR=0.30, 95% CI 0.07–1.25; p=0.10) (Table 3). Due to the small number of AT1RB users, we did not perform a sub-analysis for this medication group.

Of the 563 RAS-AHM, 116 were BBB-C and 447 BBB-NC medications. In the fully adjusted models, BBB-C was not superior in risk reduction to BBB-NC or Other-AHM; BBB-NC was not superior to Other-AHM (Table 3).

The results were not altered after adjusting interaction terms for intervention arm.

3.3. Association between RAS-AHM use and cognitive function

In fully adjusted models, RAS-AHM users had significantly better cognitive function when compared to Other-AHM users for TMT, part B (β =−16.4 [5.60)], p=0.004); DSST (β =2.6 [0.90], p=0.005); RAVLT, delayed recall β =2.3 (0.81), p=0.005 and Composite score β =0.17 (0.06), p=0.008, (Table 4).

Table 4.

Linear regression results: Association between type of AHM use and cognitive function

| Outcome | Medication Group (Reference is Other-AHM) | Cognitive Function | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted for Demographics^ | Adjusted for Demographics and Health Characteristics^^ | |||||

| Beta (SE) | p-value | Beta (SE) | p-value | Beta (SE) | p-value | ||

| RAS vs. Other AHM | |||||||

| 3MSE | RAS-AHM | 0.64 (0.61) |

0.30 | 0.75 (0.54) |

0.16 | 0.75 (0.56) |

0.18 |

| TMT, part A | RAS-AHM | −3.3 (1.7) |

0.05 | −2.4 (1.6) |

0.13 | −3.0 (1.6) |

0.07 |

| TMT, part B | RAS-AHM | −17.0 (5.8) |

0.003 | −14.9 (5.4) |

0.006 | −16.4 (5.6) |

0.003 |

| Stroop | RAS-AHM | −2.9 (1.4) |

0.04 | −1.9 (1.4) |

0.18 | −2.0 (1.5) |

0.18 |

| DSST | RAS-AHM | 3.1 (0.95) |

0.001 | 2.4 (0.87) |

0.006 | 2.6 (0.90) |

0.004 |

| RAVLT delayed | RAS-AHM | 3.5 (0.86) |

<.0001 | 2.2 (0.79) |

0.006 | 2.3 (0.81) |

0.005 |

| Composite z-score | RAS-AHM | 0.22 (0.07) |

0.003 | 0.16 (0.06) |

0.01 | 0.17 (0.06) |

0.008 |

| ACE-I¥ vs. Other AHM | |||||||

| 3MSE | ACE-I | 1.7 (0.73) |

0.02 | 1.5 (0.68) |

0.03 | 1.3 (0.71) |

0.07 |

| TMT, part A | ACE-I | −4.0 (1.9) |

0.03 | −2.3 (1.9) |

0.23 | −2.3 (2.0) |

0.24 |

| TMT, part B | ACE-I | −17.2 (7.7) |

0.03 | −8.7 (7.1) |

0.22 | −9.7 (7.5) |

0.20 |

| Stroop | ACE-I | −3.2 (2.0) |

0.11 | −1.7 (2.0) |

0.40 | −1.4 (2.1) |

0.51 |

| DSST | ACE-I | 2.6 (1.2) |

0.03 | 1.7 (1.1) |

0.12 | 2.2 (1.1) |

0.06 |

| RAVLT delayed | ACE-I | 3.1 (1.3) |

0.01 | 1.4 (1.2) |

0.22 | 1.4 (1.2) |

0.25 |

| Composite z-score | ACE-I | 0.24 (0.09) |

0.008 | 0.15 (0.08) |

0.07 | 0.16 (0.08) |

0.05 |

| Blood-Brain Barrier Crossing RAS / non-Blood-Brain Barrier Crossing RAS vs. Other AHM | |||||||

| 3MSE | BBB-C | 0.73 (0.81) |

0.57 | 1.2 (0.71) |

0.24 | 1.2 (0.72) |

0.26 |

| BBB-NC | 0.61 (0.63) |

0.63 (0.55) |

0.63 (0.57) |

||||

| TMT, part A | BBB-C | −3.5 (2.2) |

0.14 | −4.0 (2.1) |

0.16 | −4.6 (2.1) |

0.09 |

| BBB-NC | −3.3 (1.7) |

−2.0 (1.6) |

−2.6 (1.7) |

||||

| TMT, part B | BBB-C | −16.3 (7.7) |

0.01 | −17.4 (7.1) |

0.02 | −18.9 (7.3) |

0.01 |

| BBB-NC | −17.2 (6.0) |

−14.2 (5.5) |

−15.8 (5.8) |

||||

| Stroop | BBB-C | −5.2 (1.9) |

0.03 | −4.8 (1.9) |

0.02 | −4.8 (1.9) |

0.03 |

| BBB-NC | −2.3 (1.5) |

−1.1 (1.5) |

−1.2 (1.5) |

||||

| DSST | BBB-C | 2.6 (1.3) |

0.004 | 2.6 (1.1) |

0.02 | 2.7 (1.2) |

0.02 |

| BBB-NC | 3.3 (1.0) |

2.3 (0.89) |

2.5 (0.9) |

||||

| RAVLT delayed | BBB-C | 5.1 (1.2) |

<.0001 | 3.6 (1.0) |

0.003 | 3.7 (1.1) |

0.0022 |

| BBB-NC | 3.0 (0.89) |

1.8 (0.8) |

1.9 (0.83) |

||||

| Composite z-score | BBB-C | 0.27 (0.10) |

0.008 | 0.26 (0.08) |

0.008 | 0.26 (0.08) |

0.007 |

| BBB-NC | 0.17 (0.04) |

0.08 (0.03) |

0.04 (0.03) |

||||

Adjusted for baseline age, sex, education, and race/ethnicity

Adjusted for baseline age, sex, education, race/ethnicity, study intervention, BMI, SBP, HgbA1C, use of diabetes medication, CVD ¥ACE-I (Angiotensin Converting Enzyme-Inhibitor)

AT1RB (Angiotensin 1 Receptor Blocker)

ACE-I users performed significantly better on 3MSE, TMT part A and B, DSST, RAVLT delayed recall, and Composite score in the unadjusted model compared to Other-AHM; however, this comparison was no longer significant after adjustment. (Table 4).

In the fully adjusted model BBB-C RAS-AHM performed significantly better than Other-AHM on TMT, part B (β =−18.9 [7.3], p=0.01); Stroop (β =−4.8 [1.9], p=0.01); DSST (β =2.7 [1.2], p=0.02); RAVLT, delayed recall (β =3.7 [1.1], p=0.001) and Composite score (β =0.26 [0.08], p=0.002) (Table 4). While BBB-NC RAS-AHM performed significantly better than Other-AHM on TMT, part B (β =−15.8 [5.8], p=0.006); DSST (β =2.5 [0.9], p=0.006); RAVLT, delayed recall (β =1.9 [0.83], p=0.02) and Composite score (β =0.15 [0.07], p=0.03) (Table 4). BBB-C performed significantly better than BBB-NC in fully adjusted model RAS-AHM on Stroop (p=0.02) and RAVLT, delayed recall (p=0.04).

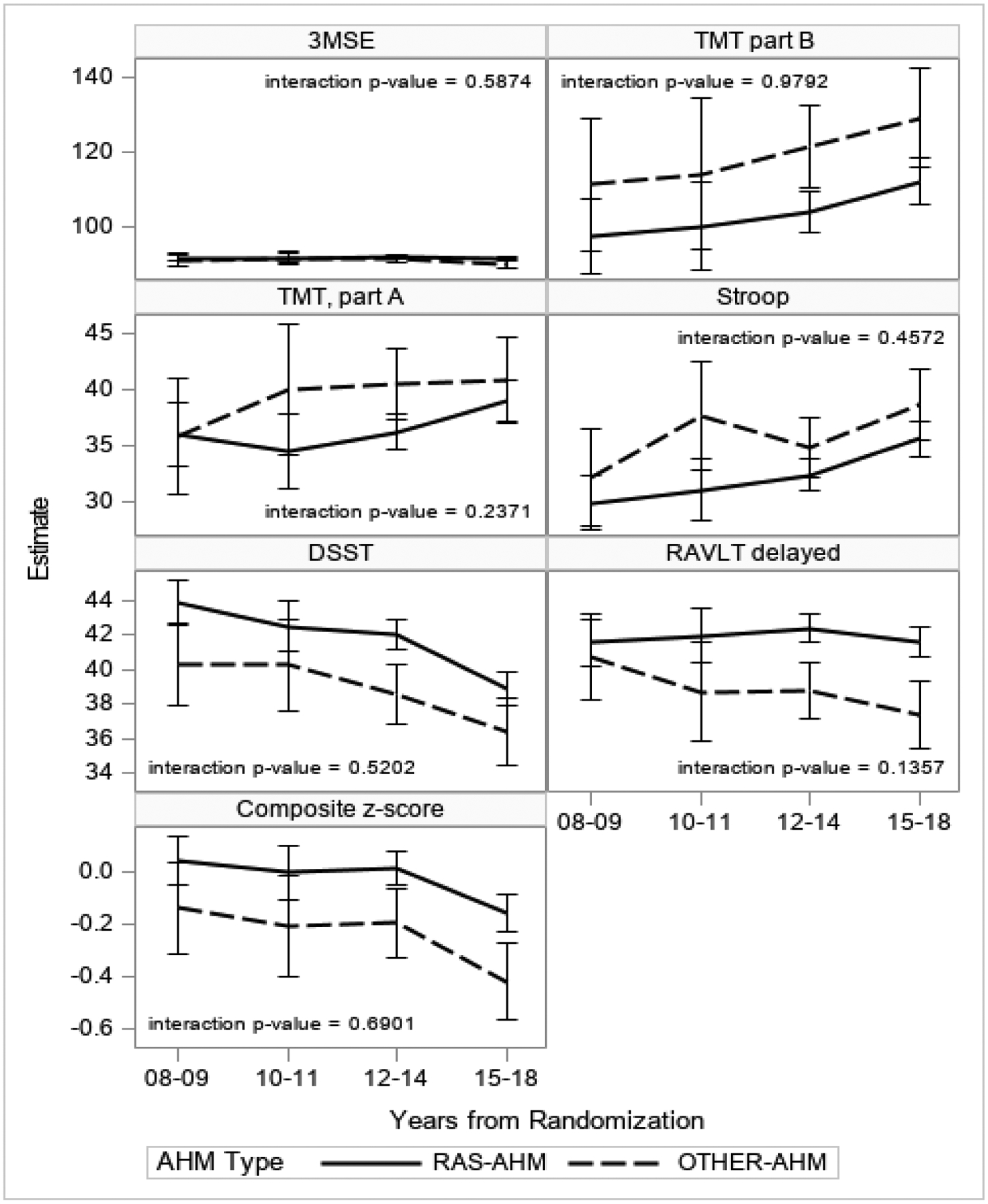

The results were not altered after adjusting interaction terms for time (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Cognitive trajectories over time by AHM use.

Estimates are from unadjusted mixed models to account for correlation within subject.

4. DISCUSSION

In this first large secondary longitudinal study of non-demented, community-dwelling participants of the Look AHEAD clinical trial with T2DM and with overweight or obesity, we evaluated associations between the use of RAS-AHM on the risk of cognitive impairment and cognitive function of key domains of cognition, including psychomotor speed, executive function, verbal learning and memory, and global cognitive function.

Our study did not find a risk reduction of cognitive impairment among RAS-AHM users compared to Other-AHM users. However, we found that RAS-AHM users over a mean 14.8-year follow-up had a significantly slower decline in processing speed, executive function, verbal memory, and composite score measures, which have been associated with cognitive decline in T2DM, compared to Other-AHM users, and this was not explained by a deleterious effect of any specific medication group within the Other-AHM (Supplemental Table 1).

RAS has been shown to be important in both T2DM and obesity. T2DM associated micro- and macrovascular complications have been linked with angiotensin II (ANGII), which has vasoconstrictive properties, and overexpression resulting in overactivation of angiotensin 1 receptor.16 ANGII also increases aldosterone production, resulting in impaired insulin signaling and worsening insulin resistance. Treatment with medication acting via the RAS-AHM has been shown to improve glucose metabolism, delay insulin resistance and prevent T2DM-associated vascular complications in numerous clinical trials;16 thus, benefits on cognitive function could be either a downstream effect on improved vascular function or improved glucose metabolism or other unmeasured effects.

We could not replicate the study findings by Kuan et al.17, which reported 26% dementia risk reduction among ACE-I users compared to non-ACE-I users and 40% dementia risk reduction among AT1RB compared to non-AT1RB users, which methodological differences could explain. Specifically, the study by Kuan et al. had a larger sample size, ACE- or AT1RB medication use was only required for 180 days allowing a larger sample size. Additionally, they compared ACE-I users to individuals who reported use of AT1RB and Other-AHM, and at the same time, they did not control for blood pressure or renal function.

Literature suggests that AT1RB are superior to ACE-I for reducing cognitive decline in people with hypertension and MCI;36 thus, we have stratified our analysis of RAS-AHM by grouping medications according to their medication class but were only able to evaluate ACE-I use and cognitive impairment risk since only a few participants reported use of AT1RB. The lack of association between ACE-I use could be partially explained by the small number of participants evident in large confident intervals. An additional explanation could be the demographic difference between AHM user groups, especially in race, sex, BMI, and CVD, which are essential determinants of dementia risk.

In our study, we replicated Ho et al.’s findings,24 a meta-analysis of 14 cohort studies evaluating the effects of RAS-AHM stratified by their BBB status in hypertensive participants on seven subjects’ cognitive domains. In our research, like the study by Ho, we found that users of BBB-C RAS-AHM did perform better on verbal memory when compared to Other-AHM and BBB-NC RAS-AHM users. Furthermore, we have found that both BBB-NC and BBB-C medication users performed better in processing speed, executive function, and composite score than Other-AHM users and that BBB-C was superior to BBB-NC in measures of executive function.

We cannot ignore the potential role of diabetes medication in AD pathology, especially metformin, which has been reported to decrease dementia risk by reducing vascular risk and provide neuroprotection independently from glycemic control,37 however, both AHM user groups reported a similar frequency of metformin use.

There are several advantages of this study. First, our study included a large, well-characterized cohort of volunteers followed for 14.8 years and had a detailed cognitive evaluation. Second, medication use was visually validated. Third, we were able to create a RAS-AHM medication group to draw a conclusion about its effect by excluding those who switched to the Other-AHM group or reported concomitant use of Other-AHM at any visit. The strength of exclusion of users of multiple AHM at the time of medication recording from our analysis may at the same time be a weakness since users of AHM may have represented a more challenging to control hypertensive group, and such individuals should be included in future studies.

This study also had some limitations. First, we cannot account for the history of hypertension, including length, severity, and AHM use. Second, we could not create a clear RAS-AHM user group with this long follow-up period who reported only RAS-AHM the whole time. Third, the observational cohort design has inherent limitations to such studies, and we cannot account for unknown or unmeasured confounders nor make assumptions regarding causality. Fourth, we did not have baseline cognitive evaluation since it was not part of the original study assessments. However, the mean age at enrollment was 58.6 years, and screening was rigorous, including an evaluation by a behavioral psychologist or interventionist to confirm they understood intervention requirements, and those with issues likely to impair adherence were excluded before enrollment. Thus, the likelihood is low that participants had cognitive impairment at baseline. Additionally, of the 2,133 participants included in our study who were followed for over 15 years and underwent cognitive adjudication, only 40 (1.9%) were diagnosed with dementia and 163 (7.6%) with MCI, reinforcing the likelihood of having cognitive impairment in this at-risk population at baseline was low. Fifth, like most randomized clinical trials, our study population was highly educated and predominantly white, limiting its generalizability. Sixth, although medications were visually inspected during visits, we did not determine compliance and did not have information on prior use of these medications. Seventh, as in all observational studies, our results may also be vulnerable to confounding. We sought to address confounding by adjusting for the average SBP during the investigation and evaluated for interaction terms between SBP and AHM use in our models. We also adjusted for history of CVD, all implicated in cognitive impairment and are the main indications for using RAS-AHM. Eighth, another potential limitation is survival bias; however, we could not evaluate the competing effect of mortality and dementia due to large intervals between cognitive assessments.

In summary, this longitudinal analysis found that RAS-AHM use in participants with T2DM and with overweight or obesity and at higher risk for cognitive decline was associated with slower decline over long-term performance on processing speed, executive function, verbal memory, and composite score. These findings could add additional information for using RAS-AHM in patients with T2DM and who have overweight or obesity. However, our study findings need to be replicated in a larger sample to understand the mechanisms by which RAS-AHM may affect cognitive impairment and function of patients with T2DM who are at increased risk for dementia and cognitive decline.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of the Look AHEAD study participants.

This research was funded by two diversity supplements to the Action for Health in Diabetes Extension Study Biostatistics Research Center (3U01DK057136-19S1 and 3 U01DK057136-19S2). The funding for the parent award is from U01DK057136.

The Action for Health in Diabetes is supported through the following cooperative agreements from the National Institutes of Health: DK57136, DK57149, DK56990, DK57177, DK57171, DK57151, DK57182, DK57131, DK57002, DK57078, DK57154, DK57178, DK57219, DK57008, DK57135, and DK56992.

The Look AHEAD Brain MRI ancillary study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services: DK092237-01 and DK092237-02S2. The Look AHEAD Movement and Memory ancillary study was supported by the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, R01AG03308701. The Look AHEAD Mind ancillary study was funded by R01AG058571.

The following federal agencies have contributed support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Nursing Research; National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities; Office of Research on Women’s Health; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and the Department of Veterans Affairs. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The Indian Health Service (I.H.S.) provided personnel, medical oversight, and use of facilities. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the I.H.S. or other funding sources.

Additional support was received from the University of Pittsburgh General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) (M01RR000056), the Clinical Translational Research Center (CTRC), funded by the Clinical & Translational Science Award (UL1 RR 024153), and NIH grant (DK 046204); Frederic C. Bartter General Clinical Research Center (M01RR01346); and the Wake Forest Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center (P30AG049638-01A1).

The following organizations have made major contributions to Look AHEAD: FedEx Corporation; Health Management Resources; LifeScan, Inc., a Johnson & Johnson Company; OPTIFAST® of Nestle HealthCare Nutrition, Inc.; Hoffmann-La Roche Inc.; Abbott Nutrition; and Slim-Fast Brand of Unilever North America.

This manuscript is based on a subset of the Look AHEAD cohort: participants from the Southwest Native American sites are not included. The complete cohort has been described (The Look AHEAD Research Group. Baseline characteristics of the randomized cohort from the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) research study. Diabetes Vasc Dis Res 2006;3:202-215 NIH Registration: NIHMS81811). The analyses performed herein were not conducted at the Look AHEAD Data Coordinating Center. This does not represent the work of the Look AHEAD study group.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Jose Luchsinger reports stipend from Wolters Kluwer as Editor in Chief of the journal Alzheimer’s Disease and Associated Disorders, Royalties from Springer as Editor of the book Diabetes and the Brain. He also received grants supporting this work, R01AG058571, and K24AG045334.

Mark Espeland reports grant funding from the NIH (R01AG064440; U24AG057437; P30AG049638; R01AG050657), the Department of Health and Human Services (HHSN271201700002C), and the Alzheimer’s Association (POINTER-19-611541).

Whitney Wharton, Andrea Anderson, Owen Carmichael, Jeanne Clark, and Sevil Yasar have no financial disclosures to disclose relevant to this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396:413–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chatterjee S, Peters SA, Woodward M, et al. Type 2 Diabetes as a Risk Factor for Dementia in Women Compared With Men: A Pooled Analysis of 2.3 Million People Comprising More Than 100,000 Cases of Dementia. Diabetes Care 2016;39:300–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbiellini Amidei C, Fayosse A, Dumurgier J, et al. Association Between Age at Diabetes Onset and Subsequent Risk of Dementia. JAMA 2021;325:1640–1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiu WC, Ho WC, Liao DL, et al. ; Health Data Analysis in Taiwan (hDATa) Research Group. Progress of Diabetic Severity and Risk of Dementia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015;100:2899–2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biessels GJ, Despa F. Cognitive decline and dementia in diabetes mellitus: mechanisms and clinical implications. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2018;14:591–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palta P, Schneider AL, Biessels GJ, et al. Magnitude of cognitive dysfunction in adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of six cognitive domains and the most frequently reported neuropsychological tests within domains. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2014. Mar;20(3):278–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen SD, Wu CL, Lin TK, et al. Renin inhibitor aliskiren exerts neuroprotection against amyloid peptide toxicity in rat cortical neurons. Neurochem Int 2012;61:369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hajjar I and Rodgers K. Do angiotensin receptor blockers prevent Alzheimer’s disease? Curr Opin Cardiol 2013;28:417–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashby EL and Kehoe PG. Current status of renin-angiotensin system-targeting antihypertensive drugs as therapeutic options for Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2013;22:1229–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vardy ERLC Rice PJ, Bowie PC, et al. Plasma angiotensin-converting enzyme in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis 2019;16:609–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sink KM, Leng X, Williamson J, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and cognitive decline in older adults with hypertension: results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1195–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li NC, Lee A, Whitmer RA, et al. Use of angiotensin receptor blockers and risk of dementia in a predominantly male population: prospective cohort analysis. BMJ 2010;340:b5465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yasar S, Xia J, Yao W, et al. Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory (GEM) Study Investigators. Antihypertensive drugs decrease risk of Alzheimer’s disease: Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory Study. Neurology 2013;81:896–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters R, Yasar S, Anderson CS, et al. Investigation of antihypertensive class, dementia, and cognitive decline: A meta-analysis. Neurology 2020;94:e267–e281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding J, Davis-Plourde KL, Sedaghat S, et al. Antihypertensive medications and risk for incident dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis of individual participant data from prospective cohort studies. Lancet Neurol 2020;19:61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsueh WA, Wyne K. Renin-Angiotensin-aldosterone system in diabetes and hypertension. J Clin Hypertens 2011;13:224–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuan YC, Huang KW, Yen DJ, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers reduced dementia risk in diabetes mellitus and hypertension patients. Int J Cardiol 2016;220:462–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryan DH, Espeland MA, Foster GD, et al. ; Look AHEAD Research Group. Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes): design and methods for a clinical trial of weight loss to prevent cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Control Clin Trials 2003;24:610–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Espeland MA, Luchsinger JA, Baker LD, et al. Look AHEAD Study Group. Effect of a long-term intensive lifestyle intervention on prevalence of cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2017;88:2026–2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayden KM, Neiberg RH, Evans JK, et al. Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) Research Group. Legacy of a 10-Year Multidomain Lifestyle Intervention on the Cognitive Trajectories of Individuals with Overweight/Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2021;50:237–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Look AHEAD Research Group, Wadden TA, West DS, et al. The Look AHEAD study: a description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting it. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14:737–752. Erratum in: Obesity 2007;15:1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wesche-Thobaben JA. The development and description of the comparison group in the Look AHEAD trial. Clin Trials 2011;8:320–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The LookAHEAD Research Group. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2013;369:145–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho JK, Moriarty F, Manly JJ, et al. Blood-Brain Barrier Crossing Renin-Angiotensin Drugs and Cognition in the Elderly: A Meta-Analysis. Hypertension. 2021. Jun 21:HYPERTENSIONAHA12117049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rey M Auditory Verbal Learning Test: A Handbook. Los Angeles, CA, Western Psychological Services; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wechsler D Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale - III (WAIS-III). San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stroop JR. Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of experimental psychology. 1935;18:643. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reitan RM. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Perceptual and Motor Skills 1958;8:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teng EL, Chui HC. The Modified Mini-Mental State (3MS) examination. J Clin Psychiatry 1987;48:314–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH Jr., et al. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol 1982;37:323–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Windblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment--beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med. 2004;256:240–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 4th ed, APA Press, Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Espeland MA, Rapp SR, Bray GA, et al. Long-term impact of behavioral weight loss intervention on cognitive function. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2014;69:1101–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Espeland MA, Carmichael O, Hayden K, et al. Long-term Impact of Weight Loss Intervention on Changes in Cognitive Function: Exploratory Analyses from the Action for Health in Diabetes Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2018;73:484–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Helmer A, Slater N, Smithgall S. A Review of ACE Inhibitors and ARBs in Black Patients with Hypertension. Ann Pharmacother 2018;52:1143–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hajjar I, Okafor M, McDaniel D, et al. Effects of Candesartan vs. Lisinopril on Neurocognitive Function in Older Adults with Executive Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2012252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liao W, Xu J, Li B, Ruan Y, Li T, Liu J. Deciphering the Roles of Metformin in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Snapshot. Front Pharmacol. 2022;12:728315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.