Abstract

In the present study, 103 Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from milk samples from 60 cows with mastitis from eight different farms in seven different locations in one region of Germany were compared pheno- and genotypically and by identification of various toxins. On the basis of culture and hemolytic properties and by determination of the tube coagulase reaction, all of the isolates could be identified as S. aureus. This could be confirmed by PCR amplification of species-specific parts of the gene encoding the 23S rRNA. In addition, all of the S. aureus isolates harbored the genes encoding staphylococcal coagulase and clumping factor and the genes encoding the X region and the immunoglobulin G binding region of protein A. These four genes displayed size polymorphisms. By PCR amplification, the genes for the toxins staphylococcal enterotoxin A (SEA), SEC, SED, SEG, SEI, SEJ, and TSST-1 but not those for SEB, SEE, SEH, and the exfoliative toxins ETA and ETB could be detected. To analyze the epidemiological relationships, the isolates were subjected to DNA fingerprinting by macrorestriction analysis of their chromosomal DNAs. According to the observed gene polymorphisms, the toxin patterns, and the information given by macrorestriction analysis of the isolates by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, a limited number of clones seemed to be responsible for the cases of bovine mastitis on the various farms.

Staphylococcus aureus is recognized worldwide as a frequent cause of subclinical intramammary infections in dairy cows. The main reservoir of S. aureus seems to be the infected quarter, and transmission between cows usually occurs during milking.

S. aureus produces a spectrum of extracellular protein toxins and virulence factors which are thought to contribute to the pathogenicity of the organism. The staphylococcal enterotoxins (SEs) are recognized agents of the staphylococcal food poisoning syndrome and may be involved in other types of infections with sequelae of shock in humans and animals (4, 25).

Nine major antigenic types of SEs have been recognized and designated SEA, SEB, SEC, SED, SEE, SEG, SEH, SEI, and SEJ (4, 5, 30, 31, 43, 50). All these toxins exhibit superantigenic activity by interacting with antigen-presenting cells and T lymphocytes without regard for the antigen specificity of the cells. This induces cellular proliferation and a high level of cytokine expression (9). A distantly related protein, toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 (TSST-1), also produced by S. aureus, was the first toxin shown to be involved in toxic shock syndrome, in both menstrual and nonmenstrual cases (3, 33). However, no immunological identity and little amino acid homology between TSST-1 and the staphylococcal enterotoxins exist (6). Some strains of S. aureus produce one or both of two immunologically distinct exfoliative toxins, exfoliative toxin A (ETA) or ETB (23, 25). These toxins have been associated with impetiginous staphylococcal diseases referred to as staphylococcal scaled skin syndrome.

At present little is known about the occurrence of these toxins among S. aureus isolates from cattle with bovine mastitis. The present study was designed to investigate S. aureus isolates from cattle with bovine subclinical mastitis from one region of Germany phenotypically, genotypically and by the identification of various toxins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection and identification.

A total of 103 S. aureus isolates were collected from milk samples from 60 cows with mastitis from eight different farms in seven different locations in one region of Germany. All of the isolates were identified by culture properties, by the detection of hemolysis (38), and by the tube coagulase reaction.

The isolates were additionally investigated by PCR amplification of species-specific parts of the gene encoding the 23S rRNA with the oligonucleotide primers shown in Table 1. For PCR amplification, the reaction mixture (30 μl) contained 1 μl of primer 1 (10 pmol/μl), 1 μl of primer 2 (10 pmol/μl), 0.6 μl of deoxynucleoside triphosphate (10 mmol/liter; MBI Fermentas, St. Leon-Rot, Germany), 3.0 μl of 10× thermophilic buffer (Promega, Mannheim, Germany), 1.8 μl of MgCl2 (25 mmol/liter; Promega), 0.1 μl of Taq DNA polymerase (5 U/μl; Promega/Boehringer), and 20.0 μl of distilled water. Finally, 2.5 μl of DNA preparation was added to each 0.2-ml reaction tube. The tubes were subjected to thermal cycling (Techne-Progene; Thermodux, Wertheim, Germany) with the program shown in Table 1. For DNA preparation, 5 to 10 colonies of the bacteria were incubated in 100 μl of TE buffer (10 mmol of Tris-HCl/liter, 1 mmol of EDTA/liter, pH 8.0) containing 5 μl of lysostaphin (1.8 U/μl; Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany), for 1 h at 37°C and subsequently treated with proteinase K (14.0 mg/ml; Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) for 120 min at 56°C. To inactivate the proteinase K, the suspension was heated for 10 min at 100°C and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 s. Ninety microliters of the supernatant was treated with 10 μl of 5-mol/liter NaClO4 and 50 μl of isopropanol (99.7%; Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany), mixed, placed on an ice block for 10 min, and centrifuged for 30 min at 13,000 rpm. The supernatant was discarded, 250 μl of ethanol (70%) was added, and the tube was again centrifuged for 5 min at 13,000 rpm. The supernatant was again discarded, and the pellet was dried in a desiccator for 5 min. After the addition of 50 μl of sterilized aqua dest, the tubes were cooled until they were used. The presence of PCR products was determined by electrophoresis of 12 μl of the reaction product in a 2% agarose gel with Tris-acetate-electrophoresis buffer (0.04 mol of Tris/liter, 1 mmol of EDTA/liter, pH 8) and a 100-bp DNA ladder (Gibco BRL, Eggenstein, Germany) as a molecular marker.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers and PCR programs for amplification of the genes encoding staphylococcal 23S rRNA and staphylococcal proteins including various toxins

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) | PCR programa | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 23S rRNA | |||

| Staur4 | ACG GAG TTA CAA AGG ACG AC | 1 | 41 |

| Staur6 | AGC TCA GCC TTA ACG AGT AC | ||

| coa | |||

| Coa-1 | ATA GAG ATG CTG GTA CAG G | 2 | 18 |

| Coa-2 | GCT TCC GAT TGT TCG ATG C | ||

| clfA | |||

| ClfA-1 | GGC TTC AGT GCT TGT AGG | 3 | 40 |

| ClfA-2 | TTT TCA GGG TCA ATA TAA GC | ||

| spa (X region) | |||

| spa-III | CAA GCA CCA AAA GAG GAA | 4 | 15 |

| spa-IV | CAC CAG GTT TAA CGA CAT | ||

| spa (IgG binding region) | |||

| spa-1 | CAC CTG CTG CAA ATG CTG CG | 2 | 35 |

| spa-2 | GGC TTG TTG TTG TCT TCC TC | ||

| sea | |||

| SEA-1 | AAA GTC CCG ATC AAT TTA TGG CTA | 5 | 47 |

| SEA-2 | GTA ATT AAC CGA AGG TTC TGT AGA | ||

| seb | |||

| SEB-1 | TCG CAT CAA ACT GAC AAA CG | 5 | 20 |

| SEB-2 | GCA GGT ACT CTA TAA GTG CC | ||

| sec | |||

| SEC-1 | GAC ATA AAA GCT AGG AAT TT | 5 | 20 |

| SEC-2 | AAA TCG GAT TAA CAT TAT CC | ||

| sed | |||

| SED-1 | CTA GTT TGG TAA TAT CTC CT | 5 | 20 |

| SED-2 | TAA TGC TAT ATC TTA TAG GG | ||

| see | |||

| SEE-1 | TAG ATA AGG TTA AAA CAA GC | 5 | 20 |

| SEE-2 | TAA CTT ACC GTG GAC CCT TC | ||

| seg | |||

| SEG-1 | AAT TAT GTG AAT GCT CAA CCC GAT C | 5 | 19 |

| SEG-2 | AAA CTT ATA TGG AAC AAA AGG TAC TAG TTC | ||

| seh | |||

| SEH-1 | CAA TCA CAT CAT ATG CGA AAG CAG | 5 | 19 |

| SEH-2 | CAT CTA CCC AAA CAT TAG CAC C | ||

| sei | |||

| SEI-1 | CTC AAG GTG ATA TTG GTG TAG G | 5 | 19 |

| SEI-2 | AAA AAA CTT ACA GGC AGT CCA TCT C | ||

| sej | |||

| SEJ-1 | CAT CAG AAC TGT TGT TCC GCT AG | 6 | 30 |

| SEJ-2 | CTG AAT TTT ACC ATC AAA GGT AC | ||

| tst | |||

| TSST-1 | ATG GCA GCA TCA GCT TGA TA | 5 | 20 |

| TSST-2 | TTT CCA ATA ACC ACC CGT TT | ||

| eta | |||

| ETA-1 | CTA GTG CAT TTG TTA TTC AA | 5 | 20 |

| ETA-2 | TGC ATT GAC ACC ATA GTA CT | ||

| etb | |||

| ETB-1 | ACG GCT ATA TAC ATT CAA TT | 5 | 20 |

| ETB-2 | TCC ATC GAT AAT ATA CCT AA |

1, 37 times (94°C, 40 s; 64°C, 1 min; 72°C, 75 s); 2, 30 times (94°C, 1 min; 58°C, 1 min; 72°C, 1 min); 3, 35 times (94°C, 1 min; 57°C, 1 min; 72°C, 1 min); 4, 30 times (94°C, 1 min; 60°C, 1 min; 72°C, 1 min); 5, 30 times (94°C, 2 min; 55°C, 2 min; 72°C, 1 min); 6, 30 times (94°C, 1 min; 62°C, 1 min; 72°C, 1 min).

PCR amplification of genes encoding staphylococcal proteins and toxins.

A PCR amplification was performed for the genes encoding staphylococcal coagulase (coa), clumping factor (clfA), protein A (spa), SEA (sea), SEB (seb), SEC (sec), SED (sed), SEE (see), SEG (seg), SEH (seh), SEI (sei), SEJ (sej), TSST-1 (tst), ETA (eta), and ETB (etb). The sequences of the oligonucleotide primers, the thermocycler programs, and the references are summarized in Table 1.

Macrorestriction analysis by PFGE.

The isolates were also investigated by digestion of their chromosomal DNAs with the restriction enzyme SmaI and subsequent separation of the fragments by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) using the Chef-Dr II pulsed-field electrophoresis system (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany). The preparation of the DNA and the program for PFGE were described previously (46). In accordance with the method of Tenover et al. (45), restriction patterns with no fragment difference were recorded as indistinguishable, restriction patterns with two to three fragments difference were recorded as closely related, and those with four and more differences were recorded as not related.

RESULTS

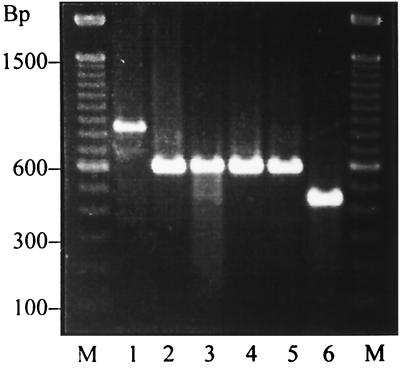

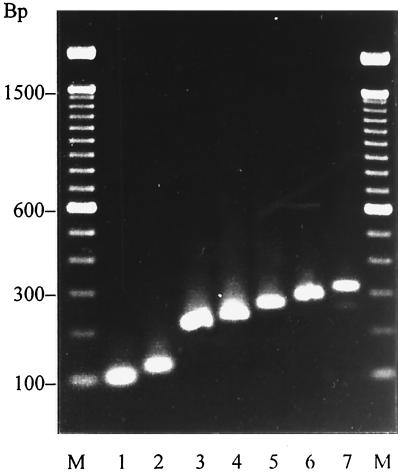

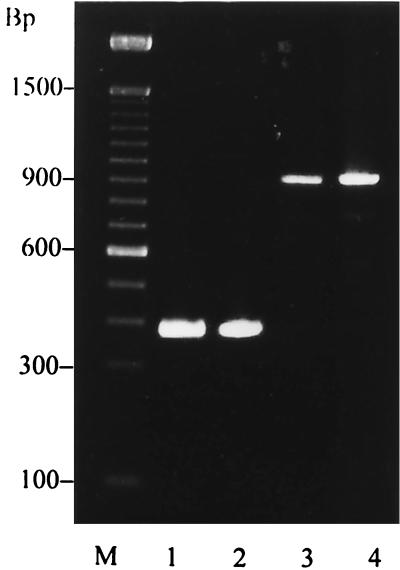

According to culture and hemolytic properties and a positive tube coagulase test, all 103 isolates used in the present study could be identified as S. aureus. Among the 103 cultures, 25 cultures showed alpha-hemolysis, 50 cultures showed beta-hemolysis, and 28 cultures were nonhemolytic (Table 2). The identification of the isolates as S. aureus could be confirmed by PCR amplification of the genes encoding the 23S rRNA, coagulase, and clumping factor and the genes encoding the X region and the immunoglobulin G (IgG) binding region of protein A. The amplicon of the 23S rRNA gene had a uniform size of 1,250 bp; all the other genes displayed polymorphisms. Typical polymorphisms of the genes encoding staphylococcal coagulase and the X region and the IgG binding region of protein A are shown in Fig. 1, 2, and 3. These results, together with the origins and hemolytic properties of the isolates, are summarized in Table 2. Among the 103 S. aureus cultures investigated, 17 cultures contained the gene encoding SEI, 21 cultures contained the genes for SEG and SEI, 21 cultures contained the genes for SED and SEJ, 15 cultures contained the genes for SEC, SEG, SEI, and TSST-1, and 1 culture contained the genes for SEA, SEC, and TSST-1. All isolates containing SEC genes were simultaneously positive for TSST-1, and all isolates containing the gene for SED were positive for SEJ. With the available oligonucleotide primers, no toxin formation could be detected for the 28 S. aureus isolates from farm 1. The distribution of toxin formation among the S. aureus isolates from the various farms is summarized in Table 2. None of the strains harbored the genes encoding SEB, SEE, SEH, ETA, or ETB.

TABLE 2.

Origin, PFGE patterns, and hemolysis and other characteristics of S. aureus isolates from milk samples from cows with bovine mastitis

| Farm | na | PFGE pattern | Hemolysis | Coagulase (coa) gene size (bp) | Clumping factor (clfA) gene size (bp) | Protein A (spa) gene size (bp)

|

Toxin PCR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG binding region | X region | |||||||

| A1 | 2 | Ia | α | 840 | 1,000 | 920 | 140 | |

| 26 | II | −c | 840 | 1,000 | 920 | 220 | ||

| B2 | 15 | IIIa | β | 600 | 1,000 | 920 | 110 | C, G, I, TSST-1 |

| 1 | IVa | β | 600 | 1,000 | 920 | 110 | G, I | |

| 1 | IVb | β | 600 | 1,000 | 920 | 110 | G, I | |

| 2 | IVc | β | 600 | 1,000 | 920 | 110 | G, I | |

| 1 | Ib | α | 840 | 1,000 | 920 | 140 | I | |

| C3 | 8 | V | α (7b), − (1) | 440 | 1,000 | 920 | 270 | G, I |

| 4 | IIIb | β | 600 | 1,000 | 920 | 110 | G, I | |

| D4 | 5 | VI | β (4), − (1) | 600 | 1,000 | 390 | 90 (1), 110 (2), 190 (2) | G, I |

| E5 | 3 | VII | α | 840 | 1,000 | 920 | 270 | I |

| 1 | VIII | β | 840 | 1,000 | 920 | 320 | I | |

| F6 | 3 | IX | α | 840 | 1,000 | 920 | 290 | I |

| G5 | 9 | X | α | 840 | 1,000 (1) | 920 | 240 (8), 170 (1) | I |

| 950 (8) | ||||||||

| H7 | 21 | XI | β | 600 | 1,000 | 920 | 270 | D, J |

| 1 | XII | β | 840 | 1,000 | 920 | 220 | A, C, TSST-1 | |

n number of strains.

Number of strains with the respective property.

−; no hemolysis.

FIG. 1.

Polymorphisms of the gene encoding staphylococcal coagulase. Lane 1, 840 bp; lanes 2, 3, 4, and 5, 600 bp; lane 6, 440 bp; M, 100-bp ladder serving as a size marker.

FIG. 2.

Amplicons of the gene encoding the X region of protein A. Lane 1, 110 bp, 3 repeats; lane 2, 140 bp, 4 repeats; lane 3, 220 bp, 7 repeats; lane 4, 240 bp, 8 repeats; lane 5, 270 bp, 9 repeats; lane 6, 290 bp, 10 repeats; lane 7, 320 bp, 11 repeats; M, 100-bp ladder.

FIG. 3.

Amplicons of the gene encoding the IgG binding region of protein A. Lanes 1 and 2, 390 bp; lanes 3 and 4, 920 bp; M, 100-bp ladder.

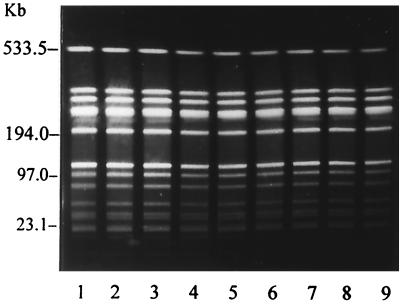

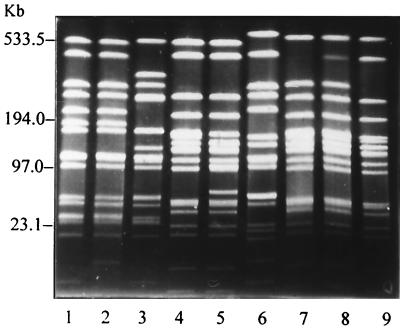

Digestion of the chromosomal DNAs of the isolates with the restriction enzyme SmaI revealed 12 different restriction patterns, with mostly identical restriction patterns for the isolates from the eight farms. A typical uniform restriction pattern of the S. aureus isolates from farm H7 and restriction patterns of S. aureus isolates representing nine different restriction patterns are shown in Fig. 4 and 5, respectively. The restriction patterns of all 103 S. aureus isolates and the above-mentioned results are summarized in Table 2. A further analysis of the 12 restriction patterns revealed that the bacterial clones with PFGE patterns Ia and Ib, IIIa and IIIb, and IVa, IVb, and IVc (all one- or two-fragment differences) and IIIa and IVb and IIIa and IVc (two- or three-fragment differences) are closely related; the remaining bacterial clones with PFGE patterns I to XII are not related (Table 2).

FIG. 4.

Pulsed-field electrophoretic restriction patterns of chromosomal DNAs of nine S. aureus isolates from farm H7 with DNA restriction pattern XI. A 0.1- to 200-kb ladder (Low Range PFG Marker; BioLabs, Schwalbach, Germany) and a 50- to 1,000-kb ladder (Lambda Ladder PFG Marker, BioLabs) served as size markers.

FIG. 5.

Pulsed-field electrophoretic restriction patterns of chromosomal DNAs of S. aureus isolates with DNA restriction patterns Ib (lane 1), Ia (lane 2), XII (lane 3), IIIa (lane 4), IIIb (lane 5), X (lane 6), IVa (lane 7), IVb (lane 8), and IVc (lane 9). A 0.1- to 200-kb ladder (Low Range PFG Marker; BioLabs, Schwalbach, Germany) and a 50- to 1,000-kb ladder (Lambda Ladder PFG Marker, BioLabs) served as size markers.

DISCUSSION

The identification of the 103 S. aureus isolates of the present study could be performed by conventional methods and by PCR technology. The latter uses oligonucleotide primers targeted to species-specific parts of the gene encoding the 23S rRNA and the genes encoding coagulase, clumping factor, and protein A. Comparable PCR-based systems for identification of S. aureus isolates from various origins have been used by numerous authors (1, 7, 13, 26, 40, 41). All these target genes allowed a rapid identification of this species with high sensitivity and specificity. As was found by Straub et al. (41), the amplification of the gene encoding an S. aureus-specific part of the 23S rRNA revealed an amplicon with a size of 1,250 bp for all S. aureus isolates investigated.

The PCR products of the genes encoding staphylococcal coagulase, clumping factor, and protein A displayed gene polymorphisms and allowed a genotypic characterization of the bacteria. Length and sequence polymorphisms of the coagulase gene and its use for genotypic characterization of S. aureus had been already shown (1, 16, 18, 37, 40, 42).

As with previous studies (40), the amplification of the clumping factor (clfA) gene resulted in a single amplicon with a size of approximately 1,000 bp, indicating no size polymorphisms of this gene. However, the clumping factor genes of eight isolates investigated in the present study had a size of 950 bp. At present, no information is available about the sequence variation of these strains.

Amplification of the X region of the protein A (spa) gene yielded a single amplicon for all 103 isolates. Ten different-sized amplicons of approximately 90, 110, 140, 170, 190, 220, 240, 270, 290, and 320 bp and calculated numbers of 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11 repeats, respectively, were observed. Comparable differences in the number of repeats of the X region of the protein A (spa) gene had already been used for genotyping isolates of this species (14, 15, 46, 48).

The PCR amplification of the gene encoding the IgG binding region of protein A revealed a size of 920 bp for most of the isolates investigated. However, the genes of five strains showed an amplicon size of 390 bp. Because in these five strains the PCR products were 390 bp smaller and because 170 bp is the fragment size that is required to encode one IgG binding domain, a lack of two domains is assumed for these strains. Comparable spa gene polymorphisms were observed by Schwarzkopf et al. (34) and Stephan et al. (40).

Investigating the S. aureus isolates for toxin formation revealed that, besides enterotoxins A, C, and D and TSST-1, the newly described enterotoxins G, I, and J seemed to be the predominant enterotoxins of S. aureus isolated from cattle with bovine mastitis. The enterotoxin studies were done by PCR amplification of the respective genes. According to Becker et al. (2), Mc Lauchlin et al. (29), and Sharma et al. (36), there is an excellent correlation between PCR results and the detection of enterotoxins by commercial reverse passive latex agglutination assays. The involvement of enterotoxin G- and I-producing S. aureus strains had been previously demonstrated for S. aureus isolates from humans with staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome and staphylococcal scarlet fever (19). Production of SEA, SEB, SED, SEE, and TSST-1 by S. aureus strains associated with bovine mastitis has been described by numerous authors (8, 24, 27, 39, 40, 44). It was interesting that all SEC producers of the present study were TSST-1 positive and all SED producers were SEJ positive. A comparable relationship between the detection of SEC and TSST-1 has been reported in the literature (11, 27, 32, 40, 51). The enterotoxins D and J are encoded by a plasmid and separated from each other by an intergenic region (50). None of the strains harbored any of the genes seb, see, seh, eta, and etb. As shown in the studies of Hayakawa et al. (17), the production of exfoliative toxins among S. aureus isolates from cattle with bovine mastitis seems to be rare.

According to the present results, the formation of enterotoxins, including the newly described enterotoxins G, I, and J, appears to be widely distributed among S. aureus isolates from the milk of mastitic cows. In the studies of Larsen et al. (22), only 1 of 414 S. aureus isolates from cattle with bovine mastitis in Denmark carried a toxin gene. However, these authors did not investigate their strains for the newly described enterotoxins SEG, SEI, and SEJ.

The importance of toxin formation by S. aureus for udder pathogenesis remains unclear. According to Ferens et al. (10), the superantigenic toxins seem to induce immunosuppression in dairy animals.

The 103 S. aureus isolates of the present study were further analyzed for epidemiological relationships by macrorestriction analysis of their chromosomal DNA by PFGE. Comparable studies had already been successfully used for investigating mastitis isolates of this species (1, 21, 40). By means of SmaI macrorestriction analysis, the isolates of the present investigation yielded 12 different PFGE patterns. The PFGE patterns of bacteria from single farms were mostly identical. Heterogeneity in other pheno- or genotypic properties among isolates of a single PFGE pattern may be due to evolutionary processes. Some of the PFGE patterns differed from each other in only a few fragments (Ia and Ib, IIIa and IIIb, and IVa, -b, and -c) and thus displayed a clonal relationship. The PFGE patterns, the size polymorphisms of the coagulase, clumping factor, and protein A genes, and the formation of the various toxins again substantiates the existence of a limited number of S. aureus clones responsible for the observed cases of bovine mastitis on the various farms. However, besides PFGE patterns Ia and Ib and IIIa and IIIb, the S. aureus clones of the present study could be found only in single farms and did not show a broad geographic distribution. This is partly in contrast to previous studies where identical or closely related S. aureus clones were responsible for the cases of bovine mastitis within herds and also between herds occurring in different regions of the world, (1, 12, 21, 28, 40, 49).

REFERENCES

- 1.Annemüller C, Lämmler C, Zschöck M. Genotyping of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine mastitis. Vet Microbiol. 1999;69:217–224. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(99)00117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Becker K, Roth R, Peters G. Rapid and specific detection of toxigenic Staphylococcus aureus: Use of two multiplex PCR enzyme immunoassays for amplification and hybridization of staphylococcal enterotoxin genes, exfoliative toxin genes, and toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2548–2553. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2548-2553.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergdoll M S, Crass B A, Reiser R F, Robbins R N, Davis J P. A new staphylococcal enterotoxin, enterotoxin F, associated with toxic shock-syndrome Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Lancet. 1981;i:1017–1021. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)92186-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergdoll M S. Enterotoxins. In: Easmon C S F, Adlam C, editors. Staphylococci and staphylococcal infections. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1983. pp. 559–598. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Betley M J, Mekalanos J J. Nucleotide sequence of the type A staphylococcal enterotoxin gene. J Bacteriol. 1987;170:34–41. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.1.34-41.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blomster-Hautamaa D A, Kreiswirth B N, Kornblum J S, Novick R P, Schlievert P M. The nucleotide and partial amino acid sequence of toxic shock syndrome toxin-1. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:15783–15786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brakstad O G, Aasbakk K, Maeland J A. Detection of Staphylococcus aureus by polymerase chain reaction amplification of the nuc gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1654–1660. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.7.1654-1660.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cardoso H F T, Silva N, Sena M J, Carmo L S. Production of enterotoxins and toxic shock syndrome toxin by Staphylococcus aureus isolated from bovine mastitis in Brazil. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1999;28:345–349. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.1999.00647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dinges M M, Orwin P M, Schlievert P M. Enterotoxins of Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:16–34. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.1.16-34.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferens W A, Davis W C, Hamilton M J, Park Y H, Deobald C F, Fox L, Bohach G. Activation of bovine lymphocyte subpopulations by staphylococcal enterotoxin C. Infect Immun. 1998;66:573–580. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.573-580.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fitzgerald J R, Hartigan P J, Meaney W J, Smyth C J. Molecular population and virulence factor analysis of Staphylococcus aureus from bovine intramammary infections. J Appl Microbiol. 2000;88:1028–1037. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.01071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fitzgerald J R, Meaney W J, Hartigan P J, Smyth C J, Kapur V. Fine-structure molecular epidemiological analysis of Staphylococcus aureus recovered from cows. Epidemiol Infect. 1997;119:261–269. doi: 10.1017/s0950268897007802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forsman P, Tilsala-Timisjärvi A, Alatossava T. Identification of staphylococcal and streptococcal causes of bovine mastitis using 16S–23S rRNA spacer regions. Microbiology. 1997;143:3491–3500. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-11-3491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frénay H M, Theelen J P, Schouls L M, Vandenbroucke-Grauls C M, Verhoef J, van Leeuwen W J, Mooi F R. Discrimination of epidemic and nonepidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains on the basis of protein A gene polymorphism. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:846–847. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.3.846-847.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frénay H M E, Bunschoten A E, Schouls L M, van Leeuwen W J, Vandenbrouke-Grauls C M J E, Verhoef J, Mooi F R. Molecular typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus on the basis of protein A gene polymorphism. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;15:60–64. doi: 10.1007/BF01586186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goh S H, Byrne S K, Zhang J L, Chow A W. Molecular typing of Staphylococcus aureus on the basis of coagulase gene polymorphisms. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1642–1645. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.7.1642-1645.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayakawa Y, Akagi M, Hayashi M, Shimano T, Komae H, Funaki O, Kaidoh T, Takeuchi S. Antibody response to toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 of Staphylococcus aureus in dairy cows. Vet Microbiol. 2000;72:321–327. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(99)00198-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hookey J V, Richardson J F, Cookson B D. Molecular typing of Staphylococcus aureus based on PCR restriction fragment length polymorphism and DNA sequence analysis of the coagulase gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1083–1089. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.4.1083-1089.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarraud S, Cozon G, Vandenesch F, Bes M, Etienne J, Lina G. Involvement of enterotoxins G and I in staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome and staphylococcal scarlet fever. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2446–2449. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2446-2449.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson W M, Tyler S D, Ewan E P, Ashton F E, Pollard D R, Rozee K R. Detection of genes for enterotoxins, exfoliative toxins, and toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 in Staphylococcus aureus by the polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:426–430. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.3.426-430.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lange C, Cardoso M, Senczek D, Schwarz S. Molecular subtyping of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from cases of bovine mastitis in Brazil. Vet Microbiol. 1999;67:127–141. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(99)00031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larsen H D, Huda A, Eriksen N H R, Jensen N E. Differences between Danish bovine and human Staphylococcus aureus isolates in possession of superantigens. Vet Microbiol. 2000;76:153–162. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(00)00232-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee C Y, Schmidt J J, Johnson-Winegar A D, Spero L, Iandolo J J. Sequence determination and comparison of the exfoliative toxin A and toxin B genes from Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:3904–3909. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.9.3904-3909.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee P K, Kreiswirth B N, Deringer J R, Projan S J, Eisner W, Smith B L, Carlson E, Novick R P, Schlievert P M. Nucleotide sequences and biologic properties of toxic shock syndrome toxin 1 from ovine- and bovine-associated Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:1056–1063. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.6.1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marrack P, Kappler J. The staphylococcal enterotoxins and their relatives. Science. 1990;248:705–711. doi: 10.1126/science.2185544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martineau F, Picard F J, Roy P H, Ouellette M, Bergeron M G. Species-specific and ubiquitous-DNA based assays for rapid identification of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:618–623. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.3.618-623.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsunaga T, Kamata S, Kakiichi N, Uchida K. Characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from peracute, acute and chronic bovine mastitis. J Vet Med Sci. 1993;55:297–300. doi: 10.1292/jvms.55.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matthews K R, Kumar S J, O'Conner S A, Harmon R J, Pankey J, Fox L K, Oliver S P. Genomic fingerprints of Staphylococcus aureus of bovine origin by polymerase chain reaction-based DNA fingerprinting. Epidemiol Infect. 1994;112:177–186. doi: 10.1017/s095026880005754x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mc Lauchlin J, Narayanan G L, Mithani V, O'Neill G. The detection of enterotoxins and toxic shock syndrome toxin genes in Staphylococcus aureus by polymerase chain reaction. J Food Prot. 2000;63:479–488. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-63.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Monday S R, Bohach G A. Use of multiplex PCR to detect classical and newly described pyrogenic toxin genes in staphylococcal isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3411–3414. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.10.3411-3414.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Munson S H, Tremaine M T, Betley M J, Welch R A. Identification and characterization of staphylococcal enterotoxin types G and I from Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3337–3348. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3337-3348.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orden J A, Cid D, Blanco M E, Ruiz Santa Quiteria J A, Gomez-Lucida E, de la Fuente R. Enterotoxin and toxic shock syndrome toxin-one production by staphylococci isolated from mastitis in sheep. APMIS. 1992;100:132–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1992.tb00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schlievert P M, Shands K N, Dan B B, Schmid G P, Nishimura R D. Identification and characterization of an exotoxin from Staphylococcus aureus associated with toxic-shock syndrome. J Infect Dis. 1981;143:509–516. doi: 10.1093/infdis/143.4.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwarzkopf A, Karch H, Schmidt H, Lenz W, Heesemann J. Phenotypical and genotypical characterization of epidemic clumping factor-negative, oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2281–2285. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.9.2281-2285.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seki K, Sakurada J, Seong H K, Murai M, Tachi H, Ishii H, Masuda S. Occurrence of coagulase serotype among Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from healthy individuals—special reference to correlation with size of protein-A gene. Microbiol Immunol. 1998;42:407–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1998.tb02302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sharma N K, Catherine E D R, Dodd C E R. Development of a single-reaction multiplex PCR toxin typing assay for Staphylococcus aureus strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:1347–1353. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.4.1347-1353.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shopsin B, Gomez M, Waddington M, Riehman M, Kreiswirth B N. Use of coagulase gene (coa) repeat region nucleotide sequences for typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3453–3456. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.9.3453-3456.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skalka B, Smola J, Pillich J. A simple method of detecting staphylococcal hemolysins. Zentbl Bakteriol Hyg Abt I Orig A. 1979;245:283–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stephan R, Dura U, Untermann F. Resistenzsituation und Enterotoxinbildungsfähigkeit von Staphylococcus aureus Stämmen aus bovinen Mastitismilchproben. Schweiz Arch Tierheilk. 1999;141:287–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stephan R, Annemüller C, Hassan A A, Lämmler C. Characterization of enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from bovine mastitis in north-east Switzerland. Vet Microbiol. 2000;2051:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(00)00341-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Straub J A, Hertel C, Hammes W P. A 23S rRNA-targeted polymerase chain reaction-based system for detection of Staphylococcus aureus in meat starter cultures and dairy products. J Food Prot. 1999;62:1150–1156. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-62.10.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Su C, Kanevsky I, Jayarao B M, Sordillo L M. Phylogenetic relationships of Staphylococcus aureus from bovine mastitis based on coagulase gene polymorphism. Vet Microbiol. 2000;71:53–58. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(99)00139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Su Y C, Wong A C L. Production of staphylococcal enterotoxin H under controlled pH and aeration. Int J Food Microbiol. 1998;39:87–91. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(97)00118-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takeuchi S, Ishiguro K, Ikegami M, Kaidoh T, Hayakawa Y. Detection of toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 gene in Staphylococcus aureus bovine isolates and bulk milk by the polymerase chain reaction. J Vet Med Sci. 1996;58:1133–1135. doi: 10.1292/jvms.58.11_1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Georing R V, Mickelsen P A, Murray B E, Persing D H, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toshkova K, Savov E, Soedarmanto I, Lämmler C, Chankova D, van Belkum A, Verbrugh H A, van Leeuwen W. Typing of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from nasal carries. Zentbl Bakteriol. 1997;286:547–559. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(97)80059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsen H Y, Chen T R. Use of the polymerase chain reaction for specific detection of type A, D, and E enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus aureus in foods. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1992;37:685–690. doi: 10.1007/BF00240750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Belkum A, Eriksen N H R, Sijmonds M, van Leeuwen W, van den Bergh M, Kluytmans J, Espersen F, Verbrugh H. Coagulase and protein A polymorphisms do not contribute to persistence of nasal colonisation by Staphylococcus aureus. J Med Microbiol. 1997;46:222–232. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-3-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zadoks R, van Leeuwen W, Barkema H, Sampimon O, Verbrugh H, Schukken Y H, van Belkum A. Application of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and binary typing as tools in veterinary clinical microbiology and molecular epidemiologic analysis of bovine and human Staphylococcus aureus isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1931–1939. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.5.1931-1939.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang S, Iandolo J J, Stewart G C. The enterotoxin D plasmid of Staphylococcus aureus encodes a second enterotoxin determinant (sej) FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;168:227–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zschöck M, Botzler D, Blöchler S, Sommerhäuser J. Arbeitstagung des Arbeitsgebietes Lebensmittelhygiene der Deutschen Veterinärmedizinischen Gesellschaft. Germany: Garmisch-Patenkirchen; 1998. Nachweis von Genen für Enterotoxine (ent) und Toxic Shock Syndrome Toxin 1 (tst) in Staphylococcus aureus-Isolaten aus subklinischer Mastitis des Rindes mittels Polymerase-Kettenreaktion; pp. 251–256. [Google Scholar]