Significance

H3Q5ser is a histone mark correlated with active gene expression during neuronal differentiation. The modification stabilizes the euchromatic mark, H3K4me3, potentiating its readout by general transcription factor IID. How local chromatin structure impacts the installation of H3Q5ser by the writer enzyme, transglutaminase 2 (TGM2), remains unclear. Here, we show that steric accessibility is the primary driver of TGM2-mediated histone monoaminylation. The modification is excluded from heterochromatin in cells and is restricted to glutamine residues within the unstructured tails of histones in nucleosomes. Unlike other histone posttranslational modification (PTM) writers, TGM2 is largely insensitive to both the local primary sequence and pre-installed PTMs surrounding accessible glutamines. Our study highlights the importance of chromatin structure in guiding the installation of epigenetic marks.

Keywords: chromatin, monoaminylation, TGM2

Abstract

Recent studies have identified serotonylation of glutamine-5 on histone H3 (H3Q5ser) as a novel posttranslational modification (PTM) associated with active transcription. While H3Q5ser is known to be installed by tissue transglutaminase 2 (TGM2), the substrate characteristics affecting deposition of the mark, at the level of both chromatin and individual nucleosomes, remain poorly understood. Here, we show that histone serotonylation is excluded from constitutive heterochromatic regions in mammalian cells. Biochemical studies reveal that the formation of higher-order chromatin structures associated with heterochromatin impose a steric barrier that is refractory to TGM2-mediated histone monoaminylation. A series of structure-activity relationship studies, including the use of DNA–barcoded nucleosome libraries, shows that steric hindrance also steers TGM2 activity at the nucleosome level, restricting monoaminylation to accessible sites within histone tails. Collectively, our data indicate that the activity of TGM2 on chromatin is dictated by substrate accessibility rather than by primary sequence determinants or by the existence of preexisting PTMs, as is the case for many other histone-modifying enzymes.

Chromatin, a nucleoprotein complex consisting of DNA and the canonical histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4, is the physiologically relevant form of the eukaryotic genome (1). Histones form an octameric protein complex around which 147 bp of DNA are spooled in 1.65 superhelical turns to form the simplest repeating unit of chromatin, the nucleosome (2). This organizational framework serves two critical purposes: (i) compacting the genome so that it fits within the nucleus (3) and (ii) regulating gene expression by dynamically managing DNA accessibility (4). The diverse roles chromatin plays in cellular processes is made possible in part through posttranslational modification (PTM) of the histone proteins (5, 6). Histone PTMs (or “marks”) may function by directly altering chromatin structure or through recruitment of nuclear factors containing “reader” domains that recognize modifications in specific sequence contexts (7, 8). The N-terminal tails of histones are heavily modified, with nearly every reactive residue having been reported to contain at least one modification chemotype (9), a notable exception being, until recently, glutamines.

Glutamines are subject to monoaminylation mediated by transglutaminases (TGs) (10, 11). Of the nine TGs, the most widely expressed member is tissue transglutaminase 2 (TGM2) (12). TGM2 transamidase activity is largely regulated by a Ca2+-dependent conformational change (13). Activation exposes an Asp-His-Cys catalytic triad, allowing for the formation of an acyl-enzyme intermediate following nucleophilic attack of the activated cysteine at a glutamine sidechain amide within the target protein (14). This intermediate is resolved through aminolysis with a primary amine to give a transamidated product. TGM2 is a remarkably promiscuous enzyme with numerous glutamine substrates, which can then be transamidated by an array of amines. Protein transamidation has been linked to many cellular processes, including extracellular matrix organization (15, 16), insulin release (17), and G protein signaling cascades (18, 19).

Recently, we reported the TGM2-mediated serotonylation of H3Q5 (i.e., transamidation of the sidechain of glutamine-5 in histone H3) with the primary amino group of the monoamine neurotransmitter, 5-hydroxytryptamine (20). Notably, the H3Q5ser modification was shown to co-occur on the same histone tail with trimethylation of lysine 4 (H3K4me3), a well-studied histone mark associated with active transcription (21). Strikingly, this dual mark (i.e., H3K4me3-H3Q5ser) correlates with permissive gene expression during neuronal differentiation. Biochemical studies indicate that H3Q5ser can augment the function of H3K4me3 by enhancing its binding affinity to the TAF3 subunit of general transcription factor IID and by preventing its removal by dedicated demethylase enzymes (22). Taken together, these results argue that histone serotonylation plays a role in the maintenance and fine-tuning of gene expression programs in neuronal development (20, 22).

Although there has been progress on the functional implications of histone serotonylation (20, 22), far less is known about what dictates whether a given histone residue or, more broadly, a region of chromatin is a substrate for TGM2. The literature on TGM2, while vast, provides no consensus on the how the enzyme selects its substrates (11, 12, 23, 24). Thus, it is unclear whether TGM2 activity on chromatin is driven by the local sequence context surrounding the target glutamine, or whether other factors are involved. In this study, we explored this question using both genomic and biochemical approaches. Chromatin immunoprecipitation and immunofluorescence data indicate that histone serotonylation is excluded from constitutive heterochromatin in mammalian cells. Building on this observation, biochemical studies using reconstituted “designer chromatin” substrates suggest TGM2 activity is directly inhibited by the generation of higher-order chromatin structure arising from binding of heterochromatin protein 1 alpha (HP1α) to the repressive mark H3K9me3. We also show that the structure of the nucleosome itself is inhibitory to TGM2 activity, restricting monoaminylation to sterically accessible glutamines on the histone tails. In stark contrast to most other histone PTM writers, we show that neither local sequence context nor preinstalled histone PTMs significantly influence TGM2 activity. Taken together, our data argue that steric accessibility, both on a local (protein structure) and on a cell-wide (chromatin context) level, dictates which histone glutamines are subject to TGM2-mediated monoaminylation.

Results

H3Q5ser Is Excluded from Constitutive Heterochromatin.

We began by assessing the genome-wide localization of the H3Q5ser mark in HeLa cells [which express TGM2 (20)], using chromatin immunoprecipitation with next-generation sequencing (ChIPseq). Note, previous ChIPseq studies employed an antibody against the dual H3K4me3-H3Q5ser mark and were thus narrowly focused on promoter-proximal regions (20). Analysis of the data revealed enrichment of the H3Q5ser mark within promoter-proximal and protein coding regions, in particular introns (Fig. 1A). By contrast, H3Q5ser was less commonly enriched within intergenic regions, a finding that prompted a direct comparison between H3Q5ser and H3K9me3, a repressive histone mark found in constitutive heterochromatin (25). Importantly, dot blot analysis using synthetic peptides confirmed no epitope occlusion effects for the two antibodies employed in these ChIPseq studies (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Visualization of normalized read counts within peaks for each mark revealed that regions enriched for H3Q5ser are not enriched for H3K9me3 and vice versa (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A and B). We generated genome browser tracks of a genic (ACTB) and an intergenic region as representative examples for each case. The permissive ACTB locus shows high enrichment of H3Q5ser but no enrichment of H3K9me3 (Fig. 1C). Conversely, an intergenic region with high H3K9me3 has little H3Q5ser enrichment (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). Comparison with publicly available ChIPseq data demonstrated that serotonylation of H3Q5 is generally correlated with euchromatin (H3K27ac and H3K4me3) but not with heterochromatin (H3K9me3 and H3K27me3) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2D). Further evidence supporting the mutual exclusion of H3Q5ser and H3K9me3 came from analysis of cells treated with a propargylated version of serotonin (5-PT), a probe that allows for efficient enrichment of monoaminylated chromatin (26). Consistent with the ChIPseq data, the H3K9me3 mark was not detected on immunoprecipitated histone H3 (Fig. 1D). We also performed immunofluorescence studies in both HeLa and U2OS cells probing for TGM2, which writes the H3Q5ser mark, and HP1α, which binds H3K9me3 and induces chromatin condensation (27–29). TGM2 exhibited a broad cellular distribution, including a clear nuclear pool, whereas HP1α was confined to the nucleus, primarily in distinct puncta characteristic of heterochromatin (27) (Fig. 1E and SI Appendix, Figs. S3 and S4). The images suggest that TGM2 is not enriched within HP1α puncta, which is in keeping with the finding that HP1α is not immunoprecipitated from the 5-PT–treated cells (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

TGM2-mediated histone monoaminylation is not enriched in constitutive heterochromatin. (A) Summary of H3Q5ser ChIPseq data in HeLa cells. Annotation of called H3Q5ser peaks with greater than fivefold enrichment over input. UTR, untranslated region; NA, not annotated; TSS, transcription start site; TTS, transcription termination site. (B) Heatmap of normalized H3Q5ser enrichment in HeLa cells (n = 3). Using the same genomic coordinates, a normalized enrichment heatmap for H3K9me3 is provided. (C) Genome browser tracks of H3Q5ser and H3K9me3 enrichment at the permissive ACTB locus in HeLa cells. (D) Immunoprecipitation of serotonylated proteins in HeLa cells. Cells were treated with a propargylated version of serotonin (5-PT), and following lysis, modified proteins were labeled with biotin using click chemistry. Biotinylated proteins were enriched by streptavidin-immunoprecipitation and analyzed by immunoblot using the indicated antibodies. The data are representative of three biological replicates. (E) Immunofluorescence images displaying cellular distribution of TGM2 and HP1α in HeLa cells (scale bar, 20 µm).

Based on the cellular data, we hypothesized that chromatin compaction by HP1α might inhibit histone monoaminylation by TGM2. To test this idea, we prepared reconstituted 12-mer nucleosome arrays containing either unmodified histones (wild-type [WT]-arrays) or H3K9me3 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A–E). Binding of HP1α to H3K9me3-arrays is known to induce a phase-separated, condensed state thought to mimic heterochromatin in cells (30–32). Thus, we imagined that this in vitro system could be used to assess the impact of chromatin condensation on TGM2 activity (Fig. 2A). Employing an established chromatin pelleting assay (30), we showed that HP1α preferentially condenses H3K9me3-arrays over WT-arrays (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A–C), a finding that is consistent with previous reports (30). As expected, this differential behavior is dependent upon a functional chromodomain [which binds H3K9me3 (29)] within the protein. We demonstrated this using a previously described HP1α mutant (W41A) in which the aromatic cage of the chromodomain is disrupted (33). In this case, chromatin condensation efficiency was not impacted by the presence of H3K9me3. We then conducted chromatin monoaminylation assays in the presence of 8 µM HP1α, a concentration where both substrates are in the same phase, thereby allowing direct comparisons to be made. These assays employed purified recombinant TGM2 and biotin cadaverine (BC) as an easily detectable monoamine donor (34) (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Consistent with our overall hypothesis, addition of HP1α to H3K9me3-arrays resulted in reduction in the levels of histone H3 monoaminylation (Fig. 2C). By contrast, no such effect was seen with WT-arrays; if anything, a modest increase in monoaminylation was observed. We also performed an analogous experiment using the aforementioned HP1αW41A mutant. In this case, we did not see a reduction in TGM2-mediated monoaminylation as a function of H3K9me3 (Fig. 2C). Instead, addition of the HP1αW41A mutant led to an approximately twofold elevation in histone monoaminylation levels on both the WT and H3K9me3 arrays. Additionally, we saw no reduction in monoaminylation when equivalent amounts of an isolated HP1α chromodomain were added to H3K9me3 arrays or when full-length HP1α was added to mononucleosome substrates containing H3K9me3 (SI Appendix, Figs. S6D and S8). Rather, we again observed an approximately twofold increase in modification for both WT and H3K9me3 mononucleosomes. While the origins of this enhancement are not clear, it is worth noting that HP1α binding to mononucleosomes has been shown to increase solvent accessibility of nucleosome core residues (30). Thus, the increased monoaminylation signal we observed may be due to exposure of otherwise inaccessible glutamine residues upon HP1α binding. Overall, these results support the idea that engagement of H3K9me3-containing nucleosome arrays by HP1α forms heterochromatin-like condensates that impede TGM2-mediated monoaminylation.

Fig. 2.

HP1α-induced chromatin condensation inhibits histone monoaminylation in vitro. (A) Workflow of in vitro assay used to assess the impact of HP1α-mediated chromatin condensation on TGM2 activity. (B) Condensation of 12-mer nucleosome arrays with HP1α. WT and H3K9me3 arrays were incubated with the indicated concentrations of HP1α or HP1αW41A mutant, and insoluble oligomers were removed by centrifugation. The amount of arrays remaining in solution was determined by ultraviolet absorption. Error bars = SD (n = 3). (C) TGM2-mediated monoaminylation of 12-mer arrays. WT- or H3K9me3-arrays were preincubated with 8 μM HP1α or HP1αW41A. The mixture was then treated with TGM2 and BC as the amine donor. Monoaminylation was detected by streptavidin immunoblot (Left) and quantified by densitometry (Right) using H3 levels as a loading control. Sample signal was normalized to that of WT-arrays in the absence of HP1α. Error bars = SD (n = 3). Significance was determined using one-way ANOVA analysis (n = 3; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001). au, arbitrary units.

TGM2 Activity on Histones Is Not Influenced by Local Sequence Determinants.

TGM2 is a promiscuous enzyme, and despite efforts to identify a consensus sequence for modification, none has been established (35–37). Given the number of glutamines present in histones (Fig. 3A and SI Appendix, Fig. S9), it is surprising that only H3Q5 has been reported to be modified in cells (20, 22, 38, 39). However, previous approaches relied heavily on antibodies that were specific for the H3Q5 modification. Our in vitro biochemical interrogation of HP1α-induced chromatin condensation suggested that glutamine accessibility is an important determinant for TGM2-mediated monoaminylation of chromatin. Consistent with this idea, we found that in the absence of DNA, histone complexes (e.g., H2A/H2B dimers and H3/H4 tetramers) are robustly modified by TGM2 on multiple histones (SI Appendix, Fig. S10A). In contrast, nucleosomes displayed dramatically reduced levels of monoaminylation, restricted to a single histone (SI Appendix, Fig. S10A). This result suggests that histones that exist within their native chromatin context are largely protected from modification.

Fig. 3.

H3Q5 and H3Q19 are nucleosomal substrates for TGM2. (A) Surface rendering of a nucleosome (Protein Data Bank 1KX5), displaying all glutamines color-coded according to their histone of origin: H2A = yellow, H2B = red, H3 = blue, H4 = green. The N-terminal tail of H3 is boxed. (B) TGM2-mediated monoaminylation of mononucleosomes containing either WT H3 or indicated Q-to-A H3 mutants. Monoaminylation with BC was detected by streptavidin immunoblot (Left) and quantified by densitometry (Right) using H3 levels as a loading control. Sample signals were normalized to that of WT nucleosomes. Error bars = SD (n = 3). (C and D) TGM2 monoaminylation of mononucleosomes containing the indicated alanine mutants in the H3 tail. Monoaminylation with BC was detected by streptavidin immunoblot (Top) and quantified by densitometry (Bottom) using H3 levels as a loading control. Sample signals were normalized against either the H3Q19A (Left) or H3Q5A mutant (Right). Error bars = SD (n = 3). au, arbitrary units.

With the exception of H3Q5 and H3Q19, all glutamines on histones reside within or close to histone-fold domains (Fig. 3A and SI Appendix, Fig. S9). We suspected that in the context of nucleosomes, only these accessible sites would be substrates for TGM2. To test this, we generated mononucleosomes containing glutamine to alanine mutations at both H3Q5 and H3Q19 and performed TGM2-mediated monoaminylation assays using the BC-based detection system (Fig. 3B and SI Appendix, Fig. S11). Mutation of either H3Q5 or H3Q19 led to an ∼50% reduction of H3 monoaminylation, while mutation of both residues led to a near complete loss of activity on nucleosomes (Fig. 3B). In the context of H3/H4 tetramers, however, mutation of both H3Q5 and H3Q19 did not completely ablate H3 modification, indicating that other sites on H3 are accessible in this context (SI Appendix, Fig. S10B).

Having shown that monoaminylation can occur at both H3Q5 and Q19, we sought to determine if the sequences surrounding these residues play any role in TGM2 substrate selection. To achieve this, we conducted an alanine scan around each modification site. Importantly, when one site was investigated (i.e., either Q5 or Q19), the other was always mutated to an alanine to preclude interpretive complications arising from having two substrate sites present simultaneously. In total, we generated 20 alanine mutants, 11 around Q5 and 9 around Q19, allowing us to scan the −4 to +9 positions for each residue (SI Appendix, Figs. S12–S16). Each of these mutants was incorporated into mononucleosomes, which were then subjected to TGM2 monoaminylation assays (Fig. 3 C and D). Although some minor differences in modification levels were observed across the set, no single alanine mutant significantly reduced monoaminylation at either Q5 or Q19. In this respect, TGM2 stands in stark contrast to other chromatin writers whose activity is often heavily determined by substrate amino acid sequence (40–42). The general tolerance of TGM2 to mutations in the H3 tail suggests that histone monoaminylation occurs in a primarily sequence-independent manner.

TGM2 Activity Is Unaffected by Preexisting Histone PTMs.

Another mechanism by which the activity of histone “writers” is governed is through “cross-talk,” whereby preexisting PTMs impact the deposition or removal of new marks (43–45). Indeed, the presence of serotonylation at Q5 has recently been found to inhibit demethylation of H3K4me3 by KDM5B (22). However, such cross-talk mechanisms have not been systematically analyzed for TGM2. We recently developed two barcoded nucleosome libraries, one composed of various histone PTMs (46, 47) and another composed of histone mutants and variants (48). Nucleosome library members each contain unique DNA barcodes, enabling experiments to be performed on the collective pools and allowing deconvolution of the resulting data using next-generation sequencing (NGS). We employed these libraries to conduct high-throughput biochemical analyses of TGM2, using our BC-based monoaminylation assay (Fig. 4A). Following treatment of each library with TGM2, monoaminylated (biotinylated) nucleosomes were immunoprecipitated using streptavidin beads, and the associated DNA was amplified by PCR and analyzed by NGS. Collectively, this allowed us to assess TGM2 activity on over 250 different chromatin substrates. Analysis of these data revealed that the vast majority of histone PTMs and mutations in the libraries had little or no effect on total levels of monoaminylation (Fig. 4B and SI Appendix, Fig. S17 A and B and Tables S4 and S5). Consistent with the alanine scan data, PTMs and mutations within the H3 tail had no major impact on TGM2 activity (Fig. 4 C and D). Indeed, there was excellent agreement between the library and alanine scan data within this region (SI Appendix, Fig. S17 C and D). Mutations and PTMs elsewhere on the nucleosome were also, for the most part, permissive to TGM2 activity. Of particular note was the tolerance of TGM2 to changes in the so-called acidic patch of the nucleosome (SI Appendix, Fig. S17E), a negatively charged epitope centered on the nucleosomal core that is essential for the activity of a wide range of chromatin modifiers and remodelers (46–48). TGM2 activity was, however, negatively impacted by mutations that map to the dyad-axis of the nucleosome (SI Appendix, Fig. S17F). Such mutations are known to affect nucleosome stability (49–51), which, conceivably, could alter histone H3 tail dynamics such that the glutamines become less sterically accessible. The library experiments also revealed an increase in TGM2 activity for those members containing the histone variants H2A.Z and H2A.V (SI Appendix, Fig. S18 A and B). Both of these variants contain unstructured C-terminal tails bearing glutamine residues, namely Q123 and Q124 (52), that could be modified by TGM2 under our library assay conditions (SI Appendix, Fig. S18C). Indeed, in follow-up studies employing individual nucleosomes, we confirmed that both of the C-terminal glutamine residues in H2A.Z/V can be monoaminylated by TGM2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S18 D–I).

Fig. 4.

TGM2 library assays. (A) Library assay workflow including treatment with enzyme and subsequent enrichment with streptavidin. Eluted DNA was analyzed by NGS. (B) Pie chart indicating library members that resulted in less, the same, or more monoaminylation relative to WT nucleosomes using log2 values of −0.75 and +0.75 as cutoffs (n = 3). (C) Summary of the effect of mutations in the H3 tail (residues 1 through 42) on monoaminylation levels. Nucleosome barcode counts for each library member were normalized to their pre-enrichment counts, and monoaminylation levels were reported relative to the average WT value on a log2 scale. Error bars = SD (n = 3). (D) Summary of the effect of histone PTMs on TGM2 activity. For clarity, only those library members containing H3 modifications are shown. Analysis was performed as in C. Next-Gen, next-generation; me, methyl; ac, acetyl; cr, crotonyl; ph, phosphorylation.

Histone Monoaminylation Is Dictated by Steric Accessibility.

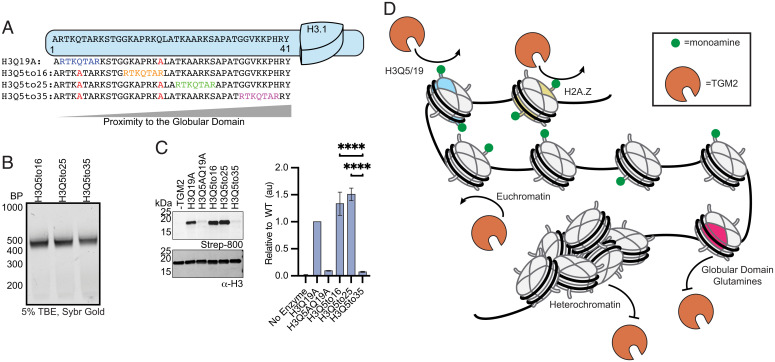

Our biochemical data converge on the idea that steric accessibility, as opposed to sequence context or PTM cross-talk, largely determines whether a given glutamine residue within histones is subject to modification by TGM2. To test this hypothesis more directly, we designed histone “slide mutants” in which we progressively moved a site of histone monoaminylation (i.e., H3Q5), within its sequence context (−3 to +3 residues), closer to the histone-fold domains (Fig. 5A). Crucially, the native glutamines at either H3Q5 or H3Q19 were mutated to alanine such that the only remaining substrate was the translocated glutamine (SI Appendix, Fig. S19). Importantly, all three H3 slide mutants formed mononucleosomes as assessed by native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis(PAGE) (Fig. 5B). We then conducted TGM2 monoaminylation assays on these substrates, again employing BC as the amine donor. Moving the Q5-centered sequence motif to position 16 or 25 in the H3 tail had no deleterious effect on monoaminylation levels (Fig. 5C). Indeed, if anything, these translocation mutants were slightly better substrates of the enzyme. By contrast, repositioning the Q5 motif to position 35, which lies at the very base of the unstructured H3 N-terminal tail (Fig. 5C), led to a precipitous drop-off in the levels of modification. This result provides strong evidence that steric accessibility of glutamine residues is the main factor dictating TGM2 activity at the mononucleosome level.

Fig. 5.

TGM2 is affected by steric accessibility. (A) Design of “slide” mutants to probe the role of nucleosome sterics on TGM2 activity. A sequence motif centered on H3Q5 was moved progressively closer to the globular domain of the histone. (B) Native PAGE analysis of nucleosomes reconstituted using H3Q5 slide octamers and standard 147-bp 601 DNA. (C) TGM2-mediated monoaminylation of mononucleosomes containing the indicated H3 slide mutants. Monoaminylation was detected by streptavidin immunoblot (Left) and quantified by densitometry (Right) using H3 levels as a loading control. The bar graph displays sample signals normalized against the H3Q19A mutant. Error bars = SD (n = 3, ****P < 0.0001). (D) Model for regulation of TGM2-mediated monoaminylation of chromatin. Sterically accessible glutamines on histone tails in euchromatin are accessible to TGM2. In contrast, globular domain glutamine residues and histones within heterochromatin are sterically inaccessible and remain unmodified. TBE, Tris-borate-EDTA; au, arbitrary units.

Discussion

Histone serotonylation is a novel PTM implicated in the up-regulation of genes during neuronal differentiation (20, 22). Initial studies on the modification have focused on its co-occurrence with the active chromatin mark, H3K4me3. Thus, the genome-wide distribution of the H3Q5ser mark on its own remained unexplored. ChIPseq studies carried out in the current study indicate that H3Q5ser is enriched in protein-coding genes and promoter-proximal regions. The relative absence of H3Q5ser within intergenic regions led us to ask whether the mark is excluded from heterochromatin. Indeed, our immunoprecipitation and immunofluorescence data are consistent with segregation of H3Q5ser and H3K9me3, the classic constitutive heterochromatin mark. Further supporting this idea, we employed designer chromatin substrates to show that HP1α-induced condensation of H3K9me3-containing nucleosome arrays impedes TGM2-mediated histone monoaminylation. Our biochemical data also indicate that at the level of individual mononucleosomes, TGM2 targets sterically accessible glutamine residues and, in contrast to other histone-modifying enzymes, is not influenced by the local sequence context or by the presence of preexisting PTMs within the substrate. Collectively, these findings shed light on the determinants guiding histone monoaminylation and lead to a model in which TGM2 activity on chromatin is under steric control (Fig. 5D).

Our in vitro analysis of the impact of HP1α on TGM2 activity yielded some unexpected results. We observed a modest increase in modification levels when unmodified 12-mer arrays were treated with concentrations of HP1α that induced a phase transition, as reflected by a classic in vitro pelleting experiment. Interestingly, this stimulatory effect was also observed when both unmodified and H3K9me3-containing arrays were exposed to a chromodomain mutant of the protein that cannot bind the H3K9me3 mark but that can still condense chromatin under the conditions of our assay. Indeed, we demonstrated the importance of the chromoshadow domain by treating arrays with an isolated chromodomain. In this case, we observed no difference between WT and H3K9me3 arrays, suggesting the importance of chromatin condensation to these differential behaviors. These observations were in stark contrast to the reduction in monoaminylation levels observed when H3K9me3 arrays were treated with WT HP1α. Taken together, these results imply that the condensates associated with HP1α engagement of H3K9me3 arrays are somehow structurally distinct from those involving unmodified arrays bound to HP1α (or the mutant HP1α bound to either type of array); the former are refractory to TMG2-mediated modification, whereas the latter are superior substrates.

Insight into the possible origins of this phenomenon comes from our analysis of mononucleosome substrates. Remarkably, we found significantly elevated (approximately twofold) levels of histone modification in the presence HP1α, irrespective of the modification state of H3K9. Previous studies have demonstrated that binding of HP1α to nucleosomes increases solvent accessibility of buried residues in the nucleosome, an effect that has been attributed to binding of the chromoshadow domain of the protein to the histone octamer core (30). We speculate that TGM2 activity is increased when nucleosome dynamics are so altered, possibly due to exposure of otherwise sterically occluded glutamine substrates. With respect to this, we note that histone dimers, tetramers, and octamers are significantly better substrates of TGM2 compared to nucleosomes, even in the presence of an H3Q5AQ19A double mutant. In the context of nucleosome arrays, we propose that this “demasking” effect accounts, at least in part, for the elevated monoaminylation levels associated with unmodified arrays in the presence of HP1α. Importantly, this stimulation appears to be overridden by whatever local steric effects are imposed when HP1α condenses H3K9me3-arrays. In regard to this, it is notable that this inhibition is not observed when using the chromodomain mutant of HP1α, indicating that inhibition requires engagement of the chromodomain with the H3K9me3 mark. Conceivably, binding of the HP1α chromodomain to H3K9me3 could locally impede access to H3Q5 by TGM2. However, the absence of any inhibitory effect using an isolated chromodomain or at the mononucleosome level would seem to argue against this. Thus, we propose that it is the nature of the higher-order structure present within the condensate that constitutes the steric barrier.

The canonical histones have a total of 18 glutamine residues between them: five in H2A, three in H2B, eight in H3, and two in H4. Our biochemical studies on reconstituted mononucleosomes indicate that only two of these residues, H3Q5 and H3Q19, are sites of monoaminylation by TGM2. Both of these Gln residues are located on the unstructured N-terminal tail of H3. By contrast, all four histones are robust substrates of TGM2 in the absence of DNA, including additional glutamines in H3. Thus, the formation of nucleosomes is broadly inhibitory to histone monoaminylation. Whether this inhibition is also manifest when non–chromatin-incorporated histones are bound to chaperones, as they would be in a cell (53), is an interesting question for future studies. Using a series of translocation mutants of H3, we demonstrated that monoaminylation is highly sensitive to steric accessibility; moving the Q5 sequence motif close to the nucleosome core drastically lowers the levels of modification. Further, in the context of our library experiments, we observed increased monoaminylation levels for those members containing the variants H2A.Z and H2A.V. Follow-up experiments showed that glutamine residues Q123 and Q124 within the unstructured C-terminal tails of these variants (not present in canonical H2A) are substrates of TGM2. Collectively, these experiments show that at the level of mononucleosomes, TGM2 activity is guided by steric accessibility.

Finally, our studies reveal that TGM2 activity is remarkably insensitive to the local primary sequence surrounding accessible glutamines. This is supported by our alanine scanning mutagenesis data as well as sequence divergence around the sites of modification within H3 and H2A.Z/H2A.V. The only residue in this dataset that appeared to have a moderate degree of importance was the Q-1 lysine residue. Mutation resulted in an increase in modification of both H3Q5 and H3Q19, an observation we attribute to the introduction of a smaller neighboring residue, possibly increasing accessibility of the glutamine residue. We previously showed that TGM2-mediated installation of H3Qser is not affected by the presence of preinstalled H3K4me3 on the same tail (20). Here, we extended this PTM cross-talk analysis by taking advantage of DNA–barcoded nucleosome libraries that allow high-throughput biochemical assays to be performed (46–48). These libraries have been used to identify positive and negative cross-talk mechanisms regulating the activity of a number of chromatin-modifying enzymes (46–48, 54, 55). In this regard, TGM2 stands out in that we did not observe any major impact (positive or negative) of preexisting PTMs on its monoaminylation activity using these library platforms. These results are in line with the principal idea emerging from the present work, namely, that it is steric accessibility rather than local sequence features (or the presence of PTMs per se) that dictates TGM2 activity on chromatin. In conclusion, we propose that this mechanism accounts for enrichment of serotonylation and, by extension, other types of monoaminylation (38, 39) within the histone H3 tails of open euchromatin.

Materials and Methods

Statistics and Reproducibility.

All TGM2 assay replicates are from independent experiments (minimum n = 3; for exact number see captions). Error bars are representative of the SD. All cell-based experiments including ChIPseq, immunofluorescence, and immunoprecipitations were repeated a total of three times to ensure reproducibility.

Cell Culture.

HeLa and U2OS cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection and grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 µg/mL streptomycin and 100 U/mL penicillin. Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2, 95% humidified incubator.

General BC TGM2 Assay.

Monoaminylation assays were performed by incubating indicated substrates (400 nM) with TGM2 (50 nM) in monoaminylation buffer A (25 mM Tris.HCl, 10 mM CaCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 10 mM KCl, pH 7.8, and 5 mM BC) for 1 h at 30 °C in a total volume of 20 µL. Following incubation, the reaction was quenched with 4X sodium dodecyl sulfate–loading buffer and analyzed by Western blotting, utilizing Strep-800 (1:10,000) and α-H3 or α-H4 (1:1,000) to control for loading. All assays were conducted as described here, with minor modifications implemented as necessary. SI Appendix contains further information.

SI Appendix describes general laboratory protocols, peptide synthesis, protein semisynthesis, protein expression and purification, nucleosome and 12-mer array assembly, TGM2 transamidation assays, barcoded library assays and analysis, HP1α-induced chromatin condensation assays, Western blotting, antibody epitope controls, cell culture protocols, ChIPseq studies, immunofluorescence microscopy, and additional information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the I.M. and T.W.M. laboratories for valuable discussions and comments. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (R37-GM096868 and P01-CA196539 to T.W.M. and R01 MH116900 and DP1 DA042078 to I.M.). I.M. is an investigator of the HHMI. M.M.M. was supported by an NIH postdoctoral fellowship (GM131632).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. S.T. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2208672119/-/DCSupplemental.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

ChIPseq data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE Accession No. 198978) (56). All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

References

- 1.McGinty R. K., Tan S., Nucleosome structure and function. Chem. Rev. 115, 2255–2273 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luger K., Mäder A. W., Richmond R. K., Sargent D. F., Richmond T. J., Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 Å resolution. Nature 389, 251–260 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Holde K. E., “The proteins of chromatin. I. Histones” in Chromatin, Rich A., Ed. (Springer Series in Molecular Biology, Springer, 1989), pp. 69–180. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Badeaux A. I., Shi Y., Emerging roles for chromatin as a signal integration and storage platform. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 14, 211–224 (2013). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strahl B. D., Allis C. D., The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature 403, 41–45 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jenuwein T., Allis C. D., Translating the histone code. Science 293, 1074–1080 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bannister A. J., Kouzarides T., Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res. 21, 381–395 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruthenburg A. J., Li H., Patel D. J., Allis C. D., Multivalent engagement of chromatin modifications by linked binding modules. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 983–994 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang H., Sabari B. R., Garcia B. A., Allis C. D., Zhao Y., SnapShot: Histone modifications. Cell 159, 458–458.e1 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walther D. J., Stahlberg S., Vowinckel J., Novel roles for biogenic monoamines: From monoamines in transglutaminase-mediated post-translational protein modification to monoaminylation deregulation diseases. FEBS J. 278, 4740–4755 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lorand L., Graham R. M., Transglutaminases: Crosslinking enzymes with pleiotropic functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 4, 140–156 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fesus L., Piacentini M., Transglutaminase 2: An enigmatic enzyme with diverse functions. Trends Biochem. Sci. 27, 534–539 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinkas D. M., Strop P., Brunger A. T., Khosla C., Transglutaminase 2 undergoes a large conformational change upon activation. PLoS Biol. 5, e327 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu S., Cerione R. A., Clardy J., Structural basis for the guanine nucleotide-binding activity of tissue transglutaminase and its regulation of transamidation activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 2743–2747 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hummerich R., Costina V., Findeisen P., Schloss P., Monoaminylation of fibrinogen and glia-derived proteins: Indication for similar mechanisms in posttranslational protein modification in blood and brain. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 6, 1130–1136 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lai T.-S., Greenberg C. S., Histaminylation of fibrinogen by tissue transglutaminase-2 (TGM-2): Potential role in modulating inflammation. Amino Acids 45, 857–864 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paulmann N., et al. , Intracellular serotonin modulates insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells by protein serotonylation. PLoS Biol. 7, e1000229 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walther D. J., et al. , Serotonylation of small GTPases is a signal transduction pathway that triggers platelet α-granule release. Cell 115, 851–862 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vowinckel J., et al. , Histaminylation of glutamine residues is a novel posttranslational modification implicated in G-protein signaling. FEBS Lett. 586, 3819–3824 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farrelly L. A., et al. , Histone serotonylation is a permissive modification that enhances TFIID binding to H3K4me3. Nature 567, 535–539 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lauberth S. M., et al. , H3K4me3 interactions with TAF3 regulate preinitiation complex assembly and selective gene activation. Cell 152, 1021–1036 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao S., et al. , Histone H3Q5 serotonylation stabilizes H3K4 methylation and potentiates its readout. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2016742118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffin M., Casadio R., Bergamini C. M., Transglutaminases: Nature’s biological glues. Biochem. J. 368, 377–396 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruoppolo M., et al. , Analysis of transglutaminase protein substrates by functional proteomics. Protein Sci. 12, 1290–1297 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becker J. S., Nicetto D., Zaret K. S., H3K9me3-dependent heterochromatin: Barrier to cell fate changes. Trends Genet. 32, 29–41 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin J. C.-Y., et al. , An in vivo tagging method reveals that Ras undergoes sustained activation upon transglutaminase-mediated protein serotonylation. ChemBioChem 14, 813–817 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verschure P. J., et al. , In vivo HP1 targeting causes large-scale chromatin condensation and enhanced histone lysine methylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 4552–4564 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munari F., et al. , Methylation of lysine 9 in histone H3 directs alternative modes of highly dynamic interaction of heterochromatin protein hHP1β with the nucleosome. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 33756–33765 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Machida S., et al. , Structural basis of heterochromatin formation by human HP1. Mol. Cell 69, 385–397.e8 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanulli S., et al. , HP1 reshapes nucleosome core to promote phase separation of heterochromatin. Nature 575, 390–394 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larson A. G., et al. , Liquid droplet formation by HP1α suggests a role for phase separation in heterochromatin. Nature 547, 236–240 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strom A. R., et al. , Phase separation drives heterochromatin domain formation. Nature 547, 241–245 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bannister A. J., et al. , Selective recognition of methylated lysine 9 on histone H3 by the HP1 chromo domain. Nature 410, 120–124 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tovar-Vidales T., Roque R., Clark A. F., Wordinger R. J., Tissue transglutaminase expression and activity in normal and glaucomatous human trabecular meshwork cells and tissues. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 49, 622–628 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hitomi K., Kitamura M., Sugimura Y., Preferred substrate sequences for transglutaminase 2: Screening using a phage-displayed peptide library. Amino Acids 36, 619–624 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dørum S., et al. , The preferred substrates for transglutaminase 2 in a complex wheat gluten digest are peptide fragments harboring celiac disease T-cell epitopes. PLoS One 5, e14056 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keresztessy Z., et al. , Phage display selection of efficient glutamine-donor substrate peptides for transglutaminase 2. Protein Sci. 15, 2466–2480 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lepack A. E., et al. , Dopaminylation of histone H3 in ventral tegmental area regulates cocaine seeking. Science 368, 197–201 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fulton S. L., et al. , Histone H3 dopaminylation in ventral tegmental area underlies heroin-induced transcriptional and behavioral plasticity in male rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 47, 1776–1783 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schuhmacher M. K., Kudithipudi S., Kusevic D., Weirich S., Jeltsch A., Activity and specificity of the human SUV39H2 protein lysine methyltransferase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1849, 55–63 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yung P. Y. K., Stuetzer A., Fischle W., Martinez A.-M., Cavalli G., Histone H3 serine 28 is essential for efficient polycomb-mediated gene repression in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 11, 1437–1445 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakanishi S., et al. , A comprehensive library of histone mutants identifies nucleosomal residues required for H3K4 methylation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 881–888 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yuan W., et al. , H3K36 methylation antagonizes PRC2-mediated H3K27 methylation. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 7983–7989 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmitges F. W., et al. , Histone methylation by PRC2 is inhibited by active chromatin marks. Mol. Cell 42, 330–341 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McGinty R. K., Kim J., Chatterjee C., Roeder R. G., Muir T. W., Chemically ubiquitylated histone H2B stimulates hDot1L-mediated intranucleosomal methylation. Nature 453, 812–816 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguyen U. T. T., et al. , Accelerated chromatin biochemistry using DNA-barcoded nucleosome libraries. Nat. Methods 11, 834–840 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dann G. P., et al. , ISWI chromatin remodellers sense nucleosome modifications to determine substrate preference. Nature 548, 607–611 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bagert J. D., et al. , Oncohistone mutations enhance chromatin remodeling and alter cell fates. Nat. Chem. Biol. 17, 403–411 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Flaus A., Rencurel C., Ferreira H., Wiechens N., Owen-Hughes T., Sin mutations alter inherent nucleosome mobility. EMBO J. 23, 343–353 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chatterjee N., et al. , Histone acetylation near the nucleosome dyad axis enhances nucleosome disassembly by RSC and SWI/SNF. Mol. Cell. Biol. 35, 4083–4092 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muthurajan U. M., et al. , Crystal structures of histone Sin mutant nucleosomes reveal altered protein-DNA interactions. EMBO J. 23, 260–271 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suto R. K., Clarkson M. J., Tremethick D. J., Luger K., Crystal structure of a nucleosome core particle containing the variant histone H2A.Z. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 1121–1124 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gurard-Levin Z. A., Quivy J.-P., Almouzni G., Histone chaperones: Assisting histone traffic and nucleosome dynamics. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 83, 487–517 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liszczak G., Diehl K. L., Dann G. P., Muir T. W., Acetylation blocks DNA damage-induced chromatin ADP-ribosylation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 14, 837–840 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mashtalir N., et al. , Chromatin landscape signals differentially dictate the activities of the mSWI/SNF family complexes. Science 373, 306–315 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.B. J. Lukasak, B. E. Dul, I. Maze, T. W. Muir, TGM2-Mediated Histone Transglutamination is Dictated by Steric Accessibility. Gene Expression Omnibus. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE198978. Deposited 18 March 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

ChIPseq data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE Accession No. 198978) (56). All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.