Abstract

Lipoteichoic acid (LTA) is associated with the cell envelope of most gram-positive bacteria. Although previously thought to act mainly as a virulence factor by virtue of its adhesive nature, evidence is now provided that LTA can also suppress the function of interleukin-2 (IL-2), an autocrine growth factor for T cells. LTA from four separate bacterial strains lowered the levels of detectable IL-2 during a peripheral blood mononuclear cell response to the antigen tetanus toxoid (TT). T-cell proliferation in response to TT was similarly inhibited by LTA. In contrast, levels of detectable gamma interferon increased. In addition, LTA inhibited IL-2 detection by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and blocked the proliferative response of an IL-2-dependent T-cell line to soluble IL-2. Further studies using ELISA demonstrated that LTA blocks IL-2 detection and function by binding directly to IL-2. Flow cytometric analysis revealed that IL-2 binding to T cells is inhibited in the presence of purified LTA but not LTA plus anti-LTA monoclonal antibody. In summary, these studies demonstrate a novel effect of LTA on the immune response through direct binding to IL-2 and inhibition of IL-2 function. Importantly, gram-positive organisms from which LTA is obtained not only play an important role in the pathology of diseases such as bacterial endocarditis, septic shock, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and multiple organ failure but also comprise a significant portion of commensal populations within the human host. Inhibition of IL-2 function by LTA may represent yet another mechanism by which gram-positive bacteria dampen the host immune response and facilitate survival. Thus, LTA provides a potential target for therapeutic intervention when gram-positive organisms are involved.

Lipoteichoic acids (LTAs) represent a highly diverse class of sugar phosphate polymers (5, 9). The LTA molecule is a polyanionic, amphipathic structure associated with the cell envelope of most gram-positive organisms and is composed of a single lipid side chain anchored to a ribitol or glycerol backbone (5, 9). Although immunogenic when administered in crude form or in conjunction with adjuvant, purified LTA by itself is not immunogenic (9, 34). Exposed at the cell surface, LTA is believed to be involved in bacterial adhesion (4, 16). LTA is also thought to function in the maintenance of enzyme activity for several membrane-associated enzymes by concentrating cations (especially Mg2+) near the cell membrane (9). In addition, there have been several studies which discuss LTA's potential inhibitory effects on the immune response (2, 12, 21, 27, 30), as well as enhancing effects such as increased macrophage activation and secretion of a number of cytokines including interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor alpha, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-12 (5, 10, 28).

IL-2 is an autocrine growth factor for T cells (31) and natural killer cells (1) and is involved in numerous facets of the immune response. Studies suggest that IL-2 produced by T cells is not only critical for T-cell replication but also important in B-cell activation (18) and the production of specific antibody (Ab) isotypes (11). Furthermore, IL-2 is integral to the maintenance of tolerance to self antigen (Ag) (17) through the downregulation of high-affinity IL-2 receptor (IL-2R) on T cells and its replacement with low-affinity receptors as foreign Ag levels decline (31). Thus, inhibition of IL-2 function by components of gram-positive organisms, specifically LTA, could have a profound impact on the host immune response to infection.

Previous studies conducted in our laboratory have demonstrated that the gram-positive organism Streptococcus mutans, when present, significantly reduces the level of detectable IL-2 produced by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in response to the Ag tetanus toxoid (TT) (26). Based on these studies and reports by others showing that LTA has the capacity to inhibit immune function (2, 12, 21, 27, 30), we explored the possibility that LTA, which is present in the majority of gram-positive organisms (34), may be the source of the IL-2 inhibition that we observed.

The present report shows that LTAs derived from multiple strains of gram-positive bacteria significantly reduce the levels of detectable IL-2 produced in response to TT. A decrease in cell proliferation in response to TT is similarly observed in the presence of LTA. In addition, a reduction in detectable IL-2 in the presence of LTA is demonstrated when using mitogen-stimulated T cells. In contrast, LTA increases the levels of gamma interferon (IFN-γ) detected in response to TT. Additional observations, including LTA's ability to interfere with IL-2 detection by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and to block the proliferation of an IL-2-dependent T-cell line to exogenously added IL-2, led to the hypothesis that there is a direct interaction between LTA and IL-2 which inhibits both IL-2 detection and IL-2 function. In this regard, evidence is provided demonstrating that LTA binds to IL-2 and inhibits the interaction between a monoclonal antibody (MAb) and the neutralizing domain of IL-2 for which the MAb is specific. Furthermore, an IL-2-dependent T-cell line fails to proliferate in the presence of IL-2 when in the form of an IL-2–LTA complex, and IL-2 fails to bind to T cells when preincubated with LTA. Importantly, the later effect is reversed in the presence of MAb to LTA.

In summary, these studies demonstrate a novel mechanism of bacterial immune suppression via the direct binding of LTA to IL-2, thus suggesting a potential role for LTA in dampening the host immune response to gram-positive organisms and prolonging bacterial survival. The recognition that LTA can act as an IL-2 inhibitor suggests the possibility that LTA may serve as a potential target for disease intervention where the balance between bacterial survival and host immunity is compromised.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

TT was obtained from Accurate Chemical and Scientific Corporation (Westbury, N.Y.). All Ag concentrations were chosen based on preliminary experiments specifically designed for assay optimization. LTAs from Streptococcus mutans, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Streptococcus faecalis, as well as phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, Mo.). Phytohemagglutinin (PHA) was purchased from Wellcome Diagnostics (Dartford, England). Recombinant human IL-2 was obtained from Intergen, Inc. (Purchase, N.Y.). Recombinant biotinylated human IL-2 was created using the PinPoint Xa3 vector system (Protocols and applications guide, 3rd ed., 1996; Promega, Madison, Wis.), and DNA for IL-2 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.). Briefly, PCR primers were designed which generate a HindIII restriction site 5′ of the IL-2 signal peptide cleavage site, with a KpnI restriction site downstream of the stop codon. The PCR product of 530 bp was inserted into the PinPoint Xa3 vector between the HindIII and KpnI restriction sites. Transformants were selected on Luria broth agar containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml and incubated overnight at 37°C. Individual colonies were screened by HindIII digestion of isolated plasmid DNA. Biotinylated IL-2 (bIL-2) was detected by Western blotting using avidin-horseradish peroxidase. The bIL-2 was purified by allowing it to bind to a monomeric avidin resin, followed by elution with a molar excess of d-biotin under nondenaturing conditions.

Cells.

PBMC were obtained from healthy donors ranging from 25 to 42 years of age and were isolated using Ficoll-Hypaque as previously described (13). PBMC from a minimum of three donors were utilized, and they generated results similar to those provided in this paper. Jurkat cells (a human T-cell line) and the IL-2-dependent murine T-cell line CTLL-2 were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection. Cell concentrations used in our assays were chosen based on preliminary experiments designed for assay optimization.

Evaluation of IL-2 levels in the presence of PBMC, TT, and LTA.

PBMC were resuspended at a concentration of 5 × 106 cells/ml in AIM V medium (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.). Three hundred seventy-five microliters of cells containing 100 μg of TT was then combined in the wells of a 12-well plate (Costar, Cambridge, Mass.) with 750-μl aliquots of LTA ranging in concentration from 0 to 75 μg/ml. Cultures were then incubated for 3 days at 37°C in 5% CO2 in a humidity chamber. On day 3, supernatants were harvested and frozen at −20°C for future analysis. IL-2 and IFN-γ were measured using ELISA kits obtained from Immunotech, Inc. (Westbrook, Maine), and the assays were carried out in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Cytokine assays were conducted at 3 days following addition of LTA to cultures, due in part to earlier studies in which a 3-day incubation period had also been used and inhibition of IL-2 had been observed (26). Furthermore, an effort was made to correlate inhibition of IL-2 with a reduction in proliferative responses (also measured at 3 days). Sources of LTA tested included S. mutans, S. aureus, S. pyogenes, and S. faecalis.

Proliferation of T cells to TT in the presence of LTA.

Two hundred microliters of PBMC containing 2.5 × 106 cells/ml was incubated for 3 days in wells of a 96-well plate (Corning, Corning, N.Y.) at 37°C in 5% CO2 with 33.3 μg of TT per ml and LTA from S. mutans ranging in concentration from 0 to 75 μg/ml. Ag and cell concentrations, as well as incubation times, were chosen based on preliminary experiments specifically designed for assay optimization. Thus, the 3-day incubation period was chosen for proliferation assays based on this prior analysis (data not shown), which indicated that 3 days was the optimal time point for measuring proliferative responses to TT under these conditions. One hundred microliters of supernatant was harvested for cytokine determinations. The proliferative response was monitored by addition of 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine (ICN Biomedicals, Los Angeles, Calif.) to the remaining volume for a period of 24 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were then harvested using a Skatron cell harvester (Skatron Instruments, Ltd., Suffolk, United Kingdom), and [3H]thymidine incorporation was measured using a RackBeta (LKB Wallac, Turku, Finland) scintillation counter. As indicated above, IL-2 and IFN-γ levels were monitored in parallel by ELISA.

Analysis of IL-2 levels in the presence of mitogen-stimulated Jurkat cells and LTA.

Two hundred fifty microliters of AIM V medium containing Jurkat cells (16 × 106 cells/ml) was combined in the wells of a 12-well plate (Costar) with 250 μl of each of the following: PHA at 0.04 μg/ml, PMA at 2 ng/ml, and LTA from S. mutans in 1:3 dilutions ranging in concentration from 0 to 150 μg/ml. The plates were then incubated for 24 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. The cells and supernatants were then harvested, and the supernatants were frozen at −20°C for future analysis. The viability of Jurkat cells exposed to LTA was measured by resuspending cells at a concentration of 2.5 × 106 cells/ml and adding 200 μl of cells to the wells of a 96-well plate. Twenty microliters of MTT (thiazolyl blue) reagent (Promega) was then added to each well, and the plate was incubated for 1 to 3 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. MTT is metabolized by viable cells, producing a change in medium color detectable at 490 nm. The plate was then read on a microplate reader (Molecular Devices Corp., Palo Alto, Calif.) at 490 nm with 610 nm as a reference wavelength.

Detection of IL-2 by ELISA following incubation of purified IL-2 with LTA.

Solutions of AIM V containing 333.3 pg of IL-2 per ml and 1:3 serial dilutions of LTA from S. mutans ranging in concentration from 0 to 25 μg/ml were incubated for 3 days at 37°C in 5% CO2. Subsequently, an ELISA was carried out in which 96-well plates (Costar) were first coated with 50 μl of 10-μg/ml IL-2-specific neutralizing MAb (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.) per well in carbonate coating buffer (pH 9.6) and allowed to incubate overnight at 4°C. Following three washes with phosphate-buffered saline containing 2 mg of bovine serum albumin (Sigma) per ml (PBS-BSA), 100 μl of test samples containing IL-2 or IL-2 plus LTA and 100 μl of an alkaline phosphatase (AP)-labeled IL-2-specific polyclonal Ab (Immunotech, Inc.) were added to the coated wells. The plates were again incubated overnight at 4°C and washed three times with PBS-BSA. Binding of the secondary Ab was measured by adding phosphatase substrate (Immunotech, Inc.), and reading at a wavelength of 405 nm on a microplate reader (Molecular Devices Corp.).

Analysis of T-cell responses to purified IL-2.

A grid system was used for the time course experiment depicted in Fig. 6 whereby 25 μl of LTA from S. mutans in 1:3 serial dilutions ranging from 0 to 25 μg/ml was added to the wells of a 96-well plate on the vertical axis, in triplicate. On the horizontal axis, 25 μl of IL-2 in 1:2 serial dilutions ranging from 166 to 1,333 pg/ml was added to wells, in triplicate. After preincubation for 6, 12, 24, or 72 h at 37°C in 5% CO2, 100 μl of 105 CTLL-2 T cells/ml (RPMI 1640, 10% fetal bovine serum, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM glutamine, 2.5 g of glucose per liter, and 1 μg of recombinant human IL-2 per ml) in CTLL-2 medium was added to wells. Prior to addition, CTLL-2 cells were washed three times in HEPES-buffered RPMI with 0.1 μg of human albumin per ml to remove residual IL-2 used to cultivate these cells. After an overnight incubation with samples at 37°C in 5% CO2, cells were pulsed with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine, incubated for 4 to 6 h at 37°C in 5% CO2, and harvested as previously described for PBMC.

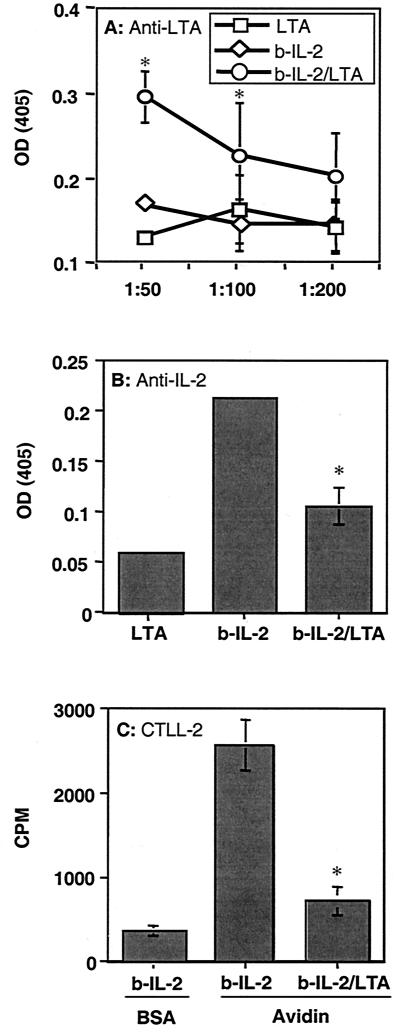

FIG. 6.

Formation of IL-2–LTA complexes blocks the binding of IL-2-specific neutralizing MAb to IL-2 and inhibits IL-2-dependent CTLL-2 proliferation. IL-2 activity following the formation of IL-2–LTA complexes was evaluated as described in Materials and Methods. Briefly, purified bIL-2 was preincubated with LTA from S. mutans overnight at 37°C, and then dilutions of 1:50, 1:100, and 1:200 were added to the wells of a 96-well plate coated with either avidin or BSA. IL-2–LTA complexes were detected using anti-LTA MAb (A). The ability of LTA to bind near the IL-2R binding domain was determined using a neutralizing anti-IL-2 MAb (B). The function of IL-2 bound by LTA was evaluated by the addition of the IL-2-dependent cell line CTLL-2 (C). Data points in each graph represent the means of three replicates ± standard deviations. Statistical analysis was done using Student's t test. Data points obtained in the presence of both IL-2 and LTA were compared to those obtained in the presence of IL-2 alone. The asterisks indicate a P value of <0.05. OD, optical density.

Detection of IL-2–LTA complexes and inhibition of IL-2 function, following complex formation.

Ten micrograms of bIL-2 per ml in PBS, alone or combined with 25 μg of S. mutans LTA per ml, was incubated overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2. At the same time, 96-well plates (Costar) were coated with 50 μl of 10-μg/ml avidin (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) per well in PBS and incubated overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, wells were washed three times with 200 μl of PBS-BSA. Wells were then blocked by addition of PBS-BSA for 1 to 4 h at room temperature. Following removal of the blocking solution, serial dilutions of bIL-2 or bIL-2 plus LTA (bIL-2–LTA) were added to wells (50 μl/well). The plate was then incubated for 2 h at room temperature on a Vari-Mix rocking platform (Thermolyne, Dubuque, Iowa).

To detect LTA bound to IL-2, the plate was washed again and 50 μl of mouse anti-LTA MAb (Chemicon, Temecula, Calif.) per well was added for 1.5 h at room temperature. Following another wash, 50 μl of AP-labeled goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G Ab (heavy and light chain) per well was incubated in the plate for 1 h (Caltag, San Francisco, Calif.) at room temperature. Finally, 100 μl of AP substrate (Sigma) per well was added to detect bound secondary Ab.

To determine whether LTA blocks the site normally recognized by the receptor for IL-2, a neutralizing mouse anti-IL-2 MAb was used in place of mouse anti-LTA MAb and detected with AP-labeled secondary Ab, as described above.

To confirm that formation of IL-2–LTA complexes prevents T cells from responding to IL-2, CTLL-2 assays were performed by capturing bIL-2 or bIL-2–LTA complexes on wells coated with avidin, as described above, under sterile conditions. Subsequently, 100 μl of CTLL-2 cells (105 cells/ml in CTLL-2 medium) was added to wells containing bIL-2 or bIL-2–LTA complexes bound to avidin. Plates were incubated overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2. The cells were then pulsed with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine, incubated for 4 to 6 h at 37°C and 5% CO2, and harvested as previously described.

Analysis of IL-2 binding to activated T cells in the presence of LTA.

To demonstrate the inhibitory effect of LTA on IL-2 binding to T cells following bIL-2–LTA conjugate formation, PHA-stimulated human PBMC were utilized. PHA specifically activates T cells, inducing IL-2R expression. IL-2 binding in the presence and absence of LTA from S. mutans was measured using flow cytometry. To obtain PHA-stimulated T cells, PBMC were resuspended in AIM V (Gibco BRL, Rockville, Md.) at 2.5 × 106 cells/ml with 5 μg of PHA (Sigma) per ml. PBMC were then incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 3 days. Prior to addition to PHA-stimulated PBMC, bIL-2 and streptavidin-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.) were combined at a 1:1 M ratio in 1× PBS to a final concentration of 60 and 120 μg/ml, respectively. The mixture was then incubated at 4°C overnight on a Vari-Mix rocker to form bIL-2–avidin–FITC conjugates. Subsequently, 60 μl of LTA ranging in concentration from 0 to 100 μg/ml (Sigma) was added to 60 μl of the IL-2–FITC conjugates containing 15 μg of bIL-2 per ml and 30 μg of avidin-FITC per μl. Samples were then incubated at 4°C overnight on a Vari-Mix rocker. PHA-stimulated PBMC were then washed three times in 10 ml of AIM V to remove free PHA and resuspended at 12.5 × 106 cells/ml in AIM V. Twenty microliters of the above bIL-2–avidin–FITC conjugates, plus or minus LTA, was then combined with 40 μl of PBMC and incubated at 4°C for 2 h with rocking on a Vari-Mix rocker. Cells were then washed three times with PBS-BSA containing 0.1% azide and resuspended in 200 μl of PBS-BSA plus azide and 200 μl of methanol-free formalin (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, N.Y.). PBMC were analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACScan (Becton Dickinson) cytometer, and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was determined. bIL-2 binding was evaluated by gating on lymphocytes and analyzing for a shift in MFI. To confirm the involvement of LTA and eliminate a role for contaminants within the LTA preparation, murine anti-LTA MAb was used to block LTA activity. PBMC and bIL-2–avidin–FITC conjugates were prepared as indicated above. However, prior to addition of LTA to IL-2–avidin–FITC conjugates, 10 μl of anti-LTA MAb (1:10 dilutions ranging from 1:7 to 1:7,000) was combined with 60 μl of LTA at 100 μg/ml and incubated at 4°C overnight on a Vari-Mix rocker. Seventy microliters of the LTA–anti-LTA mixtures was then combined with 60 μl of the IL-2–avidin–FITC conjugates and incubated at 4°C overnight on a Vari-Mix rocker. Twenty microliters of the above mixture was then added to 40 μl of PHA-stimulated PBMC at 12.5 × 106 cells/ml. Cells were then incubated and fixed as described above for LTA–bIL-2–avidin–FITC mixtures. MFI was then measured, also as indicated above.

RESULTS

LTA reduces detectable IL-2 levels produced by PBMC in response to TT.

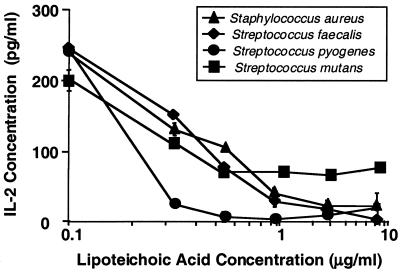

Previous studies suggested that S. mutans, when added to cultures containing PBMC and TT, could reduce the amount of IL-2 detected in response to TT (26). Therefore, we explored the possibility that LTA, a component of most gram-positive organisms, may be responsible for this inhibition. To provide evidence that LTA can inhibit IL-2 in a manner similar to that observed in previous studies using whole S. mutans (26), we incubated for 3 days LTA isolated from several different bacterial strains (S. mutans, S. aureus, S. pyogenes, and S. faecalis) with PBMC which were concurrently stimulated with TT. Our results show a clear correlation between the level of IL-2 detected and the amount of LTA present from each gram-positive organism tested: S. mutans, S. aureus, S. faecalis, and S. pyogenes (Fig. 1). Specifically, the higher the concentration of LTA present during the PBMC response to TT, the lower the amount of IL-2 detected. LTA obtained from S. pyogenes appeared to be the most potent in this regard.

FIG. 1.

Reduced IL-2 detection in the presence of PBMC, TT, and LTA purified from S. aureus, S. faecalis, S. pyogenes, and S. mutans. PBMC and TT were incubated in AIM V for 3 days at 37°C with purified LTA from four different strains of gram-positive bacteria as described in Materials and Methods. IL-2 levels were then measured using ELISA. Data points shown represent the means of triplicate samples ± standard deviations.

LTA inhibits TT-induced T-cell proliferation.

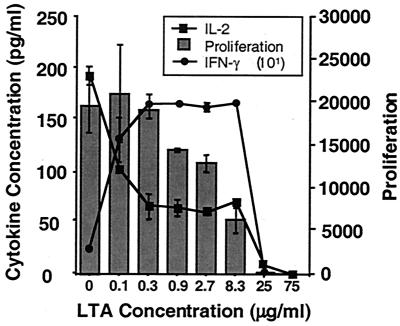

IL-2 is an autocrine growth factor for T cells and thus plays an important role in driving T-cell proliferation in response to Ag. We therefore sought to determine whether LTA might also interfere with T-cell proliferation in response to TT. In addition, we determined whether such an effect could be correlated with a simultaneous reduction in detectable IL-2 and whether another T-cell-derived cytokine, IFN-γ, would be similarly affected. PBMC were combined for 3 days with TT and increasing concentrations of LTA from S. mutans. A 3-day incubation period was chosen in this case to maximize our ability to correlate cytokine levels with levels of proliferation, also measured on day 3. After 3 days at 37°C, proliferation was measured using [3H]thymidine incorporation, and IL-2 and IFN-γ levels were measured by ELISA. Three individual experiments showed a steady reduction in TT-induced PBMC proliferation upon the addition of increasing levels of LTA (Fig. 2). This also correlated with a reduction in detectable IL-2. Conversely, levels of detectable IFN-γ increased in the presence of LTA (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

LTA blocks IL-2 detection, and PBMC proliferation, while stimulating increased levels of detectable IFN-γ. PBMC were combined with TT and increasing concentrations of LTA from S. mutans as described in Materials and Methods. After 3 days at 37°C, proliferation was measured using [3H]thymidine. IL-2 and IFN-γ levels were measured by ELISA. Data points represent the means of three replicates ± standard deviations.

Inhibition of IL-2 by LTA does not require accessory cells or involve a reduction in T-cell viability.

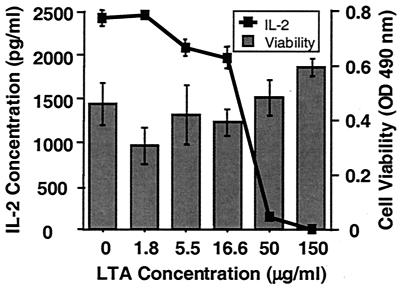

The use of whole PBMC in our experiments left open the possibility that the inhibition that we observed could be due to an effect of LTA on cells other than T cells. More specifically, suppressive molecules produced by these cells could influence IL-2 production and/or IL-2 activity. Alternatively, LTA may be toxic to T cells, thereby also reducing IL-2 production and proliferation. Hence, we titrated LTA into a culture of mitogen-stimulated Jurkat cells, a T-cell line known to produce IL-2 when activated (36). In three separate experiments, we again detected a dose-dependent decrease in the level of IL-2 as LTA concentrations increased (Fig. 3). This effect was not due to a reduction in T-cell viability mediated by LTA, since cell viability remained high despite the increased levels of LTA required to detect IL-2 inhibition using the Jurkat cell line (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Reduced IL-2 detection in the presence of LTA and a mitogen-stimulated T-cell line. The T-cell line Jurkat was stimulated to produce IL-2 with PMA and PHA in AIM V in the presence of increasing amounts of purified LTA from S. mutans, as described in Materials and Methods. IL-2 levels were then measured by ELISA after a 24-h incubation at 37°C. Cell viability was also monitored after 24 h using the metabolic dye MTT. Data points represent the means of triplicate samples ± standard deviations. OD, optical density.

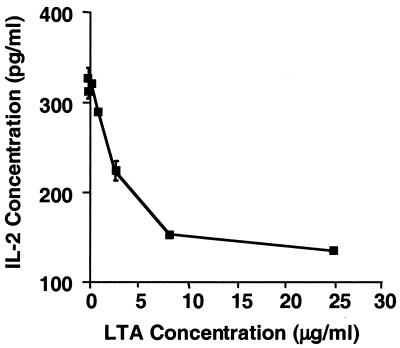

LTA inhibits detection of IL-2 protein by ELISA.

Another possibility that we considered was that LTA may interfere with the detection of IL-2 by ELISA. While preliminary studies in which LTA was added directly to ELISA mixtures had suggested that this was not the case (data not shown), these studies did not address whether LTA could interfere with detection of IL-2 following preincubation with LTA at 37°C prior to ELISA. More specifically, simultaneous addition of IL-2 and LTA to wells may have allowed sufficient time for IL-2 to bind to IL-2-specific MAb in ELISA wells, prior to LTA being able to bind to IL-2. To determine whether IL-2 detection could be blocked by preincubation of IL-2 with LTA, purified IL-2 was preincubated with increasing concentrations of LTA from S. mutans for 3 days at 37°C as indicated in Materials and Methods. IL-2 concentration was then determined by an ELISA in which the IL-2 was first captured using an IL-2-specific neutralizing MAb. In fact, when LTA was allowed to interact with IL-2 for 3 days at 37°C, we observed a dose-dependent decrease in the detection of purified IL-2 by ELISA compared to IL-2 incubated alone (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

LTA blocks detection of IL-2 in a capture ELISA that utilizes an IL-2-specific neutralizing MAb to capture IL-2. Purified IL-2 was preincubated with increasing concentrations of LTA from S. mutans for 3 days at 37°C, as indicated in Materials and Methods. IL-2 concentration was then evaluated by an ELISA in which the IL-2 was first captured using an IL-2-specific neutralizing MAb. Data points represent the means of three replicate samples ± standard deviations.

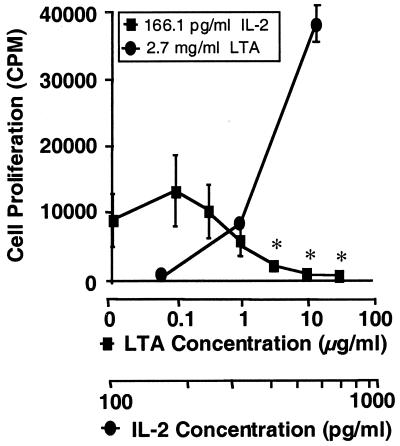

LTA blocks the response of an IL-2-dependent T-cell line to purified IL-2.

The ability of LTA to inhibit T-cell proliferation in response to TT and interfere with IL-2 detection by ELISA suggested the possibility that LTA interacts directly with IL-2, thereby interfering not only with IL-2 detection but also with IL-2 function. If this were the case, one would expect LTA to prevent proliferation of an IL-2-dependent T-cell line to purified IL-2 preincubated with LTA. To demonstrate this, as well as to determine whether a full 3-day preincubation period is required for LTA to exert its effect, time course studies were performed in which IL-2 was preincubated with LTA for various times ranging from 6 to 72 h at 37°C. IL-2 function was then monitored by addition of the IL-2-dependent T-cell line CTLL-2. As shown in Fig. 5, LTA exerts its effect with as few as 6 h of preincubation with IL-2. This effect was not a result of cell death induced by LTA, since CTLL-2 proliferation was restored with the addition of exogenous IL-2.

FIG. 5.

LTA inhibits proliferation of an IL-2-dependent T-cell line in response to purified IL-2. As described in Materials and Methods, a constant concentration of IL-2 (166.1 pg/ml) was preincubated for 6 h at 37°C with increasing concentrations of LTA from S. mutans. Proliferation of the IL-2-dependent T-cell line CTLL-2 in response to IL-2 was then measured (squares). Similarly, at a constant concentration of LTA shown to be inhibitory (2.7 μg/ml), excess IL-2 was added (circles). As indicated above, the 6-h time point of a 6- to 72-h time course is shown. Data points represent the means of three replicate samples ± standard deviations. Statistical analysis was done using Student's t test. All data points were compared to those obtained in the presence of IL-2 (166.1 pg/ml) and the absence of LTA. The asterisks indicate a P value of <0.05.

LTA binds to IL-2 and, as a result, blocks both the binding of IL-2 neutralizing MAb and the ability of an IL-2-dependent T-cell line to proliferate to IL-2.

Based on the preceding studies, we hypothesized that LTA binds directly to IL-2, thereby blocking the region important for IL-2 interaction with its receptor on T cells. To test this hypothesis, we conducted an experiment analogous to immunoprecipitation, but with ELISA, in which IL-2–LTA complexes were removed from solution and the complex was then detected. We first generated a bIL-2 which could bind to the wells of a 96-well plate when coated with avidin. Should our hypothesis be correct, preincubation of LTA with bIL-2 should result in the capture of bIL-2–LTA complexes that could then be detected with anti-LTA MAb. In contrast, MAb to the neutralizing domain of IL-2 should not bind to bIL-2–LTA complexes. In addition, an IL-2-dependent T-cell line should not respond once bIL-2–LTA complexes have formed. Three separate experiments were carried out to demonstrate this, in which the results were similar to those depicted in Fig. 6. Following the binding of bIL-2 to avidin, LTA was detected by anti-LTA MAb (Fig. 6A). This binding was significantly higher than that of LTA alone and was not observed when wells were coated with BSA. Furthermore, LTA binding reduced the ability of a neutralizing MAb to detect IL-2 (Fig. 6B), and CTLL-2 cells failed to proliferate in response to bIL-2 when in the form of bIL-2–LTA complexes (Fig. 6C).

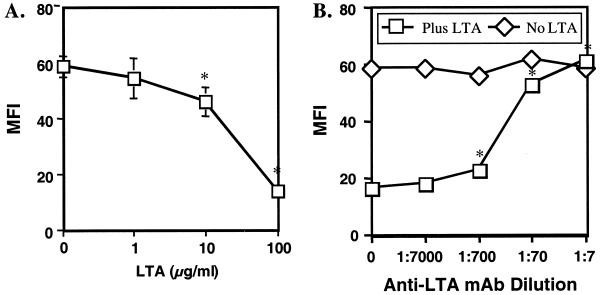

IL-2 binding to T cells is blocked in the presence of LTA alone but not in the presence of LTA plus anti-LTA MAb.

To further test the above hypothesis and to confirm the role of LTA, an additional experiment was conducted. The above hypothesis is based on the assumption that LTA binding to IL-2 prevents IL-2 interaction with the T cell and that this effect is due to the LTA within our purified LTA preparations. To confirm this, a flow cytometric IL-2 binding assay was employed. bIL-2 was incubated with avidin-FITC to form bIL-2–avidin–FITC conjugates. At the same time, LTA was incubated either alone or with anti-LTA MAb. The latter LTA–anti-LTA preparations were then combined with bIL-2–avidin–FITC conjugates and added to PHA-activated T cells. Binding of bIL-2 to activated T cells was subsequently measured by flow cytometry. As expected, LTA alone reduced the binding of bIL-2–avidin–FITC to T cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7A). In contrast, addition of anti-LTA MAb to the LTA preparation prior to incubation with bIL-2–avidin–FITC reversed this effect, also in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7B).

FIG. 7.

Reduced binding of IL-2 to T cells in the presence of LTA and its reversal by addition of anti-LTA MAb. (A) As described in Materials and Methods, PBMC were stimulated in the presence of PHA to induce IL-2R expression. bIL-2 was combined with streptavidin-FITC to obtain FITC-labeled IL-2. S. mutans LTA was then incubated at concentrations ranging from 0 to 100 μg/ml with IL-2–FITC overnight at 4°C and added to PBMC preparations. bIL-2 binding was evaluated by gating the cytokine on lymphocytes and measuring it as MFI. Data represent the means of triplicate samples ± standard deviations. (B) S. mutans LTA was added to bIL-2–avidin–FITC as indicated in panel A using a final concentration of 100 μg of LTA per ml. However, prior to addition of LTA to bIL-2–avidin–FITC, murine anti-LTA antibody was added in various amounts and incubated overnight at 4°C. bIL-2–avidin–FITC binding was measured as MFI by flow cytometry. Data represent the means of triplicate samples ± standard deviations. Statistical analysis was done using Student's t test. In panel A, all data points were compared to those obtained in the presence of bIL-2 and the absence of LTA. In panel B, all data points were compared to those obtained in the presence of bIL-2 and LTA but the absence of antibody. The asterisks indicate a P value of <0.05.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies from our laboratory have demonstrated a lack of detectable IL-2 protein produced in response to S. mutans, as well as S. mutans-dependent IL-2 inhibition in the presence of PBMC responding to the Ag TT (26). LTA is present in the majority of gram-positive organisms and has been shown elsewhere to mediate both inhibitory (2, 12, 21, 27, 30) and enhancing (5, 10, 28) effects on the immune response. Based on this and our previous observations, we explored the possibility that LTA was the molecule responsible for the inhibition of IL-2 that we observed.

In the studies reported here, we observed a dose-dependent decrease in the levels of detectable IL-2 produced by PBMC in response to TT as the concentration of LTA present was increased (Fig. 1). This would appear to be in contrast to a study by Okamato et al. showing that an LTA-like molecule stimulates IL-2 production (24). While the cited study does not provide clear evidence that LTA is the molecule being tested, our study does not exclude the ability of LTA to induce production of IL-2. It does suggest that LTA can interfere with IL-2 detection and function. Furthermore, significant variation in the potency of LTA was observed between LTA obtained from S. pyogenes and that from other bacterial strains examined. While this finding may represent a qualitative difference between the LTA preparations obtained, it could also reflect structural differences between the LTAs tested. In the latter case, LTA could potentially provide a selective advantage for S. pyogenes, assuming its impact is to reduce the amount of IL-2 available to T cells.

We also observed that, as the concentration of LTA increased, there was a reduction not only in detectable IL-2, as shown in Fig. 1, but also in the overall proliferative response to TT (Fig. 2). In contrast, detectable levels of IFN-γ increased in the presence of LTA (Fig. 2). This latter observation is significant in that it suggests a level of LTA specificity for IL-2. Furthermore, other reports have demonstrated low levels of IL-2 produced in response to gram-positive organisms. For example, Muller-Alouf et al. detected significant levels of IFN-γ generated in response to whole heat-killed S. pyogenes but failed to detect IL-2 or IL-4 (23). In addition, components of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria have been shown previously to interfere with the production as well as the release of specific cytokines (2, 35).

Although it could be clearly demonstrated that LTA impacts the level of IL-2 detected in response to TT, the mechanism involved was not clear. Since PBMC were used, it was possible that cell types other than IL-2-producing T cells were responsible for the apparent inhibition of IL-2. Specifically, the release of prostaglandins (15, 19, 25) or inhibitory cytokines (6, 37) by cells other than those producing IL-2 could result in reduced IL-2 production. To address this issue, we incubated LTA with mitogen-stimulated Jurkat cells, a T-cell line that produces IL-2 when activated with PHA and PMA (36) and monitored IL-2 protein levels. These experiments clearly demonstrated that LTA exerts its effect on IL-2 independently of cell populations other than the IL-2-secreting T cells (Fig. 3). This suggested a direct effect of LTA either on the T cells themselves or on the IL-2 being produced. Cell death due to LTA-induced toxicity in this case was ruled out, since no significant reduction in the viability of Jurkat cells was observed regardless of the LTA concentration used (Fig. 3).

Previous reports have demonstrated that bacterial components, including LTA, have the ability to inhibit cytokine production (2, 35). However, preliminary data in which IL-2 mRNA levels were evaluated did not support this hypothesis (data not shown). Another potential explanation to consider was that LTA interferes with IL-2 detection and function. To evaluate this scenario, a capture ELISA was employed in which wells were coated with a neutralizing MAb to IL-2. This MAb binds to the IL-2R binding site on IL-2 and, if blocked, would suggest that LTA interacts with the same site as the IL-2R. In fact, when LTA was allowed to interact with IL-2 for 3 days at 37°C, we did observe a dose-dependent decrease in the amount of IL-2 detected as the concentration of LTA increased (Fig. 4). Controls included IL-2 alone, incubated in the same manner. This finding suggested a direct interaction between LTA and IL-2, which prevents the binding of a neutralizing anti-LTA MAb. Thus, one might also expect IL-2 function to be impaired. In fact, this proved to be so in that the IL-2-dependent T-cell line, CTLL-2, failed to proliferate to purified IL-2 preincubated with LTA for as little as 6 h (Fig. 5). As with experiments using Jurkat cells, this effect did not appear to be due to LTA toxicity, since suppression of IL-2 by LTA was overcome by addition of exogenous IL-2 (Fig. 5). Together, data presented in Fig. 4 and 5 support the model that LTA inhibits IL-2 function by binding to IL-2 protein. Furthermore, the conclusion that LTA binds to IL-2 is bolstered by studies which report that LTA can bind to some proteins (29), as well as some components of human cell membranes (7, 14, 20). To further demonstrate that LTA interferes with IL-2 detection and function by direct binding to IL-2, a series of additional experiments were undertaken using a capture ELISA and flow cytometry. In the case of ELISA, bIL-2 was mixed with LTA, and bIL-2–LTA complexes bound to avidin were detected by ELISA (Fig. 6A). Also, binding of MAb to the neutralizing domain of IL-2 was examined (Fig. 6B), as well as CTLL-2 cell responses to the bIL-2 within the bIL-2–LTA complexes (Fig. 6C). Not only were bIL-2–LTA complexes detected by anti-LTA MAb but binding of the anti-IL-2 neutralizing MAb was inhibited as a result of complex formation. Furthermore, CTLL-2 cells did not respond to bIL-2 when in the form of bIL-2–LTA complexes.

Despite the above observations supporting the hypothesis that LTA blocks IL-2 function by direct binding, it remained possible that, although we were able to detect bIL-2–LTA complexes bound to avidin (Fig. 6B), the reduced binding of anti-IL-2 MAb and reduced CTLL-2 proliferation in response to bIL-2 (Fig. 6C) may have been due, in part, to LTA interference with the binding of bIL-2 to avidin. It was also possible that, although we used purified LTA preparations and were able to observe formation of IL-2–LTA complexes, a contaminant, and not LTA, may be responsible for the inhibition that we observed. Therefore, we conducted an additional set of experiments using flow cytometry in which we examined bIL-2 binding to activated T cells after the formation of biotin avidin linkages (bIL-2–avidin–FITC). We observed that binding was inhibited in the presence of LTA alone and that this inhibition was reversed when LTA was preincubated with anti-LTA MAb (Fig. 7). These results clearly showed the ability of the LTA preparation to block IL-2 binding to T cells and the ability of an anti-LTA MAb to reverse this effect, thereby confirming LTA's role in this process.

It is not entirely clear whether the inhibitory concentrations observed in vitro can be reached in vivo. The 50% inhibitory concentration for LTA in our experiments ranged from 0.1 to 50 μg/ml, depending on the type of assay being conducted (Fig. 1 to 5 and 7). These levels are similar to those observed in vitro following antibiotic-mediated lysis of LTA-bearing bacteria (32, 33). In any case, one might predict that relatively high local concentrations may be reached at a site of infection where bacterial destruction is ongoing. Nevertheless, in vivo studies will be required to resolve this issue.

In summary, we have demonstrated a novel function for LTA. The data presented here support the conclusion that LTA, once released from a gram-positive bacterium, can physically bind to IL-2 and interfere with its ability to stimulate T-cell proliferation. Based on these studies, we have formulated a model for the interaction between IL-2 and LTA, which prevents the binding of IL-2 to its receptor. Specifically, IL-2 has a basic pI that imparts to it a positive charge at neutral pH (22). LTA is amphipathic and thus contains both positive and negative charges (5, 14). We postulate that the negatively charged region of LTA interacts with basic residues found near the IL-2R binding pocket on IL-2. Such an interaction would likely interfere with the ability of IL-2 to interact with its receptor on T cells. In fact, studies have indicated that, by virtue of its negative charge, LTA can inhibit the binding of scavenger receptor to its ligand (14). Our studies do not exclude the possibility that other molecules derived from gram-positive bacteria may work in a similar manner. Also, we have not determined whether functional IL-2 may be recovered from the IL-2–LTA complex. Furthermore, while IFN-γ production and detection appeared unaffected, it has not been determined if LTA similarly impacts other cytokines. Additional studies will be required to resolve these issues.

Since IL-2 performs many functions critical in the successful elimination of pathogens (3, 8, 11, 18, 31), LTA release could significantly dampen the immune response to organisms such as S. pyogenes, as well as negatively impact responses to other infectious agents, when gram-positive organisms are involved. Thus, LTA may not only provide a selective advantage to gram-positive organisms in general but may also interfere with ongoing responses to other infectious agents. Understanding this function of LTA may permit LTA to serve as a potential target for therapeutic intervention during infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Flow Cytometry Core Facility at Albany Medical College.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants AI-35327, AI-40442, AI-46968, and DE-10058 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bancroft G. The role of natural killer cells in innate resistance to infection. Curr Opin Immunol. 1993;5:503–510. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90030-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blease K, Chen Y, Hellewell P G, Burke-Gaffney A. Lipoteichoic acid inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced adhesion molecule expression and IL-8 release in human lung microvascular endothelial cells. J Immunol. 1999;163:6139–6147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calvert J E, Johnstone R, Duggan-Keen M F, Bird P. Immunoglobulin G subclasses secreted by human B cells in vitro in response to interleukin-2 and polyclonal activators. Immunology. 1990;70:162–167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciardi J E, Rolla G, Bowen W H, Reilly J A. Absorption of Streptococcus mutans lipoteichoic acid to hydroxyapatite. Scand J Dent Res. 1977;85:387–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1977.tb00570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cleveland M G, Gorham J D, Murphy T L, Tuomanen E, Murphy K M. Lipoteichoic acid preparations of gram-positive bacteria induce interleukin-12 through a CD-14-dependent pathway. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1906–1912. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.1906-1912.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook G, Campbell J D, Carr C E, Boyd K S, Franklin I M. Transforming growth factor beta from multiple myeloma cells inhibits proliferation and IL-2 responsiveness in T lymphocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:981–988. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.6.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Courtney H S, von Hunolstein C, Dale J B, Bronze M S, Beachey E H, Hasty D L. Lipoteichoic acid and M protein: dual adhesins of group A streptococci. Microb Pathog. 1992;12:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90054-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Jong R, Janson A A, Faber W R, Naafs B, Ottenhoff T H. IL-2 and IL-12 act in synergy to overcome antigen-specific T cell unresponsiveness in mycobacterial disease. J Immunol. 1997;159:786–793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dziarski R. Teichoic acids. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1976;74:113–135. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-66336-9_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.English B K, Patrick C C, Orlicek S L, McCordic R, Shenep J L. Lipoteichoic acid from viridans streptococci induces the production of tumor necrosis factor and nitric oxide by murine macrophages. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:1348–1351. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.6.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flores-Romo L, Millsum M J, Gillis S, Stubbs P, Sykes C, Gordon J. Immunoglobulin isotype production by cycling human B lymphocytes in response to recombinant cytokines and anti-IgM. Immunology. 1990;69:342–347. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ginsburg I, Quie P G. Modulation of human polymorphonuclear leukocyte chemotaxis by leukocyte extracts, bacterial products, inflammatory exudates, and polyelectrolytes. Inflammation. 1980;4:301–311. doi: 10.1007/BF00915031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gosselin E J, Brown M F, Anderson C L, Zipf T F, Guyre P M. The monoclonal Ab 41H16 detects the Leu 4 responder form of human FcγRII. J Immunol. 1990;144:1817–1822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenberg J W, Fischer W, Joiner K A. Influence of lipoteichoic acid structure on recognition by the macrophage scavenger receptor. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3318–3325. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3318-3325.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gurlo T, Huang W W, von Grafenstein H. PGE2 inhibits IL-2 and IL-4-dependent proliferation of CTLL-2 and HT2 cells. Cytokine. 1998;10:265–274. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1997.0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hogg S D, Manning J E. Inhibition of adhesion of viridans streptococci to fibronectin-coated hydroxyapatite beads by lipoteichoic acid. J Appl Bacteriol. 1988;65:483–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1988.tb01921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horak I. Immunodeficiency in IL-2-knockout mice. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1995;76:S172–S173. doi: 10.1016/s0090-1229(95)90126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson-Leger C, Christenson J R, Holman M, Klaus G G B. Evidence for a critical role for IL-2 in CD40-mediated activation of naïve B cells by primary CD4 T cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:4618–4626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolenko V, Rayman P, Roy B, Cathcart M K, O'Shea J, Tubbs R, Rybicki L, Bukowski R, Finke J. Downregulation of JAK3 protein levels in T lymphocytes by prostaglandin E2 and other cyclic adenosine monophosphate-elevating agents: impact on interleukin-2 receptor signaling pathway. Blood. 1999;93:2308–2318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCloskey J J, Szombathy S, Swift A J, Conrad D, Winkelstein J A. The binding of pneumococcal lipoteichoic acid to human erythrocytes. Microb Pathog. 1993;14:23–31. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1993.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller G A, Jackson R W. The effect of streptococcus pyogenes teichoic acid on the immune response of mice. J Immunol. 1973;110:148–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mochizuki D, Watson J, Gillis S. Biochemical and biologic characterization of lymphocyte regulatory molecules. IV. Purification of interleukin 2 from a murine T cell lymphoma. J Immunol. 1980;125:2579–2583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muller-Alouf H, Alouf J E, Gerlach D, Ozegowski J-H, Fitting C, Cavaillon J-M. Human pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine patterns induced by Streptococcus pyogenes erythrogenic (pyrogenic) exotoxin A and C superantigens. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1450–1453. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.4.1450-1453.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okamato M, Ohe G, Oshikawa T, Nishikawa H, Furuichi S, Yoshida H, Matsuno T, Saito M, Satao M. Induction of Th1-type cytokines by lipoteichoic acid-related preparation isolated from OK-432, a penicillin-killed streptococcal agent. Immunopharmacology. 2000;49:363–376. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(00)00252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinge-Filho P, Tadokoro C E, Abrahamsohn I A. Prostaglandins mediate suppression of lymphocyte proliferation and cytokine synthesis in acute Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Cell Immunol. 1999;193:90–98. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1999.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plitnick L M, Banas J A, Jelley-Gibbs D M, O'Neil J, Christian T, Mudzinski S P, Gosselin E J. Inhibition of IL-2 by a gram-positive bacterium, Streptococcus mutans. Immunology. 1998;95:522–528. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00631.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raynor R H, Scott D F, Best G K. Lipoteichoic acid inhibition of phagocytosis of Staphylococcus aureus by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1981;19:181–189. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(81)90061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riva S, Nolli M L, Lutz M B, Citterio S, Girolomoni G, Winzler C, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P. Bacteria and bacterial cell wall constituents induce the production of regulatory cytokines in dendritic cell clones. J Inflamm. 1996;46:98–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott M G, Gold M R, Hancock R E. Interaction of cationic peptides with lipoteichoic acid and gram-positive bacteria. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6445–6453. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6445-6453.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silvestri L J, Knox K W, Wicken A J, Hoffmann E M. Inhibition of complement-mediated lysis of sheep erythrocytes by cell-free preparations from Streptococcus mutans BHT. J Immunol. 1979;122:54–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith K A. Interleukin-2: inception, impact, and implications. Science. 1988;240:1169–1176. doi: 10.1126/science.3131876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stuertz K, Schmidt H, Eiffert H, Schwartz P, Mader M, Nau R. Differential release of lipoteichoic acids from Streptococcus pneumoniae as a result of exposure to β-lactam antibiotics, rifamycins, trovafloxacin, and quinupristin-dalfopristin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:277–281. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.2.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Langevelde P, van Dissel J T, Ravensbergen E, Appelmelk B J, Schrijver I A, Groeneveld P H P. Antibiotic-induced release of lipoteichoic acid and peptidoglycan from Staphylococcus aureus: quantitative measurements and biological reactivities. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:3073–3078. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.12.3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wicken A J, Knox K W. Lipoteichoic acids: a new class of bacterial antigen. Science. 1975;187:1161–1167. doi: 10.1126/science.46620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson M, Seymour R, Henderson B. Bacterial perturbation of cytokine networks. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2401–2409. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2401-2409.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiskocil R, Weiss A, Imboden J, Kamin-Lewis R, Stobo J. Activation of a human T cell line: a two-stimulus requirement in the pretranslational events involved in the coordinate expression of interleukin-2 and γ-interferon genes. J Immunol. 1985;134:1599–1603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zella D, Romerio F, Curreli S, Secchiero P, Cicala C, Zagury D, Gallo R C. IFN-alpha 2b reduces IL-2 production and IL-2 receptor function in primary CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:2296–2302. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]