Abstract

A promising new strategy emerged in bone tissue engineering is to incorporate black phosphorus (BP) into polymer scaffolds, fabricating nanocomposite hydrogel platforms with biocompatibility, degradation controllability, and osteogenic capacity. BP quantum dot is a new concept and stands out recently among the BP family due to its tiny structure and a series of excellent characteristics. In this study, BP was processed into nanosheets of three different sizes via different exfoliation strategies and then incorporated into cross-linkable oligo[poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate] (OPF) to produce nanocomposite hydrogels for bone regeneration. The three different BP nanosheets were designated as BP-L, BP-M, and BP-S, with a corresponding diameter of 242.3 ± 90.0, 107.1 ± 47.9, and 18.8 ± 4.6 nm. The degradation kinetics and osteogenic capacity of MC3T3 pre-osteoblasts in vitro were both dependent on the BP size. BP exhibited a controllable degradation rate, which increased with the decrease of the size of the nanosheets, coupled with the release of phosphate in vitro. The osteogenic capacity of the hydrogels was promoted with the addition of all BP nanosheets, compared with OPF hydrogel alone. The smallest BP quantum dots was shown to be optimal in enhancing MC3T3 cell behaviors, including spreading, distribution, proliferation, and differentiation on the OPF hydrogels. These results reinforced that the supplementation of BP quantum dots into OPF nanocomposite hydrogel scaffolds could potentially find application in the restoration of bone defects.

Keywords: black phosphorus, hydrogel, osteogenesis, quantum dot, size effect

1 ∣. INTRODUCTION

As a new member of the two-dimensional (2D) layered materials, black phosphorus (BP) has aroused tremendous attention since its reemergence in 2014.1,2 Inspired by exceptional properties such as tunable band gap,3 high charge carrier mobility,4 and the excellent ON–OFF current ratio,5 scientists have dedicated efforts to the application of BP in the field of electronic and optoelectronic devices. In recent years, the area of BP-related research has expanded to biomedical applications, including cancer therapy, biosensors, and drug delivery.6

Confirmed as a biodegradable material, BP provides the merit that its final degradation product, phosphate, which commonly exists within cells and blood, is harmless to the human body in moderation.7 Meanwhile, phosphate is a major component of cell structure,8 such as cell membranes, nucleic acid, and adenosine triphosphate, and also helps to regulate bone mineralization and bone resorption, therefore making BP an attractive 2D material in bone tissue engineering. Our previous research and other published studies have found that followed by the exfoliation and integration, BP nanosheet-based hydrogel platform could be used to accelerate bone regeneration via a sustained supply of phosphate.9,10 However, BP nanosheets have been reported to be cytotoxic in certain conditions,11 limiting the further application of BP nanosheets as biomaterials. For this reason, more efforts are needed in the regulation and improvement of BP.

BP quantum dot is a kind of new form of BP nanostructure that was first prepared in 2015 via a liquid exfoliation method,12 exhibiting unique electronic and optical properties due to the quantum confinement and edge effects.13 In comparison with BP nanosheet, this ultra-small nanomaterial demonstrated less cytotoxicity and higher biocompatibility,14 reinforcing the substitution of BP quantum dot as a more promising biomaterial in the BP family. However, currently, the utilization of BP quantum dots for bone tissue engineering is still in its infancy, and there is an urgent requirement for researches focused on the osteogenesis of BP quantum dots.

In this study, a synthetic polymer, oligo[(polyethylene glycol) fumarate] (OPF), which was illustrated outstanding properties in our previous researches such as biocompatible, injectable, and biodegradable,15-17 was employed to fabricate the hydrogel platform and BP carrier. Before incorporation, the sizes of fabricated BP nanomaterials were determined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM). After that, the degradation behavior and resulting phosphate release of varying sizes of BP incorporated in OPF hydrogels were quantified. The functionalized hydrogels were then cultured with MC3T3-E1 mouse pre-osteoblast cells to assess cytocompatibility and osteoconductivity, to testify the size effect on the osteogenesis of BP in the nanocomposite hydrogel system.

2 ∣. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 ∣. Prepare of BP nanosheets and quantum dots

BP nanosheets in different sizes were prepared using a liquid exfoliation technique refer to a previous study.18 The three different sizes of BP nanosheets are abbreviated as BP-L (large size), BP-M (medium size), and BP-S (small size). The detailed ultrasonic process was specified in the supplementary materials. The concentration of the fabricated BP aqueous solution was 100 ppm as calculated according to the consumption of BP crystals.

2.2 ∣. Characterization of BP nanosheets and quantum dots

2.2.1 ∣. Subsidence

Three types of BP aqueous solutions were settled for 8, 24, and 48 h. The size effects of BP on the subsidence velocity were recorded by a digital camera.

2.2.2 ∣. AFM

AFM was used to evaluate the layer height of BP nanosheets and quantum dots according to previously published protocols.19 Briefly, the fabricated BP aqueous solutions were dropped onto the top of fresh-surface mica discs (Ted Pella). After dried under nitrogen flushing, nanoscale AFM images were taken via a Nanoscope IV PicoFroce Multimode AFM (Bruker, Camarillo, CA) at room temperature, with the machine's contact mode.

2.2.3 ∣. TEM

The diameter of BP nanosheets and quantum dots was measured by TEM images of BP samples, which were acquired on a transmission electron microscope (JEOL-1400, JEOL Inc., Japan) at 80 kV voltage.

2.2.4 ∣. Quantitative statistics

Further quantitative analysis of the TEM and AFM images was conducted using ImageJ software. In each group, 200 BP nanosheets or quantum dots on the images were selected randomly to calculate the average diameter and height. The normal distribution curves were also drawn based on the data distribution.

2.3 ∣. Preparation of BP-incorporated hydrogels

OPF polymer was synthesized using previously published protocols.17,20 The detailed procedure was specified in the supplementary materials. BP-incorporated OPF hydrogels were fabricated using chemical crosslinking. In brief, 1 g of OPF polymer and 36 mg of N,N′-methylenebisacrylamide were dissolved in 2 ml of ddH2O or BP/ddH2O (100 ppm), followed by the addition of 0.1 ml ammonium persulfate/ddH2O (0.5 g/ml) and 0.1 ml N,N,N′, N′-tetramethylethylenediamine/ddH2O (0.5 ml/ml). Immediately, the reaction mixture was transferred to a 0.8 mm-thick silicone rubber mold sandwiched between two glass plates, and kept at 37°C for 4 h. Based on the different BP/ddH2O solution types (pure ddH2O, BP-L/ddH2O solution, BP-M/ddH2O solution, and BP-S/ddH2O solution), the fabricated hydrogels were designated as OPF, OPF@BP-L, OPF@BP-M, and OPF@BP-S, respectively.

2.4 ∣. Characterization of BP-incorporated hydrogel

2.4.1 ∣. Gross view

The images of hydrogels were recorded by a digital camera.

2.4.2 ∣. SEM

Before scanning, fabricated hydrogel discs were dried by lyophilization and sputter-coated with gold–palladium. The morphology of hydrogels was observed on a scanning electron microscope (S-4700, Hitachi Instruments, Tokyo, Japan) at a voltage of 5 kV. The energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) and element mapping were viewed simultaneously at a voltage of 15 kV.

2.4.3 ∣. BP degradation and phosphate release

Hydrogel specimens were separately immersed in 1 ml of ddH2O and kept under 37°C. The solutions were changed into fresh ddH2O every 24 h, and the phosphate concentration in the extract solutions were measured via the phosphate assay kit (ab65622, Abcam) to demonstrate the phosphate release kinetics of the hydrogels. Then, the conversion rate (defined as the mole fraction of PO43−) and the half-life (defined as the time taken to release half of the maximum amount of phosphate) of BP were calculated further. Effect of BP degradation on pH was evaluated after hydrogels specimens were immersed in ddH2O and PBS for 3 days.

2.5 ∣. Pre-osteoblasts cell culture on nanocomposite hydrogels

2.5.1 ∣. Cell culture

MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblast cells were enrolled for in vitro study. Culture medium (CM) was prepared with minimum essential medium alpha without ascorbic acid (MEM-α), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 0.5% penicillin–streptomycin. Osteogenic medium (OM) was composed of CM, 50 μM ascorbic acid, 10 mM β-Glycerophosphate, and 100 nM dexamethasone.

2.5.2 ∣. Cytotoxicity

Transwell was used to determine whether nanocomposite hydrogels could release cytotoxic substances. The sterilized hydrogels were placed into chambers and MC3T3 cells were seeded in the wells at a concentration of 30,000 cells cm−2. After 4 days of culture, an MTS assay (CellTiter 96, Promega) was performed to quantify the cell number. The cell viability in positive control wells without hydrogels was defined as 100% and used to normalize the corresponding cell viability in other wells.

2.5.3 ∣. Cell proliferation

Hydrogel discs were firmly set on each well bottom of 48-well plates and pretreated with CM for 2 h. MC3T3 cells were then seeded onto hydrogel discs directly at a density of 30,000 cells cm−2. After being cultured for 1 and 6 days, cells were stained with a live/dead cell imaging kit (Invitrogen) to evaluate the cell viability and imaged with a digital Axiovert 25 Zeiss light microscope. At 1, 4, and 7 days post-seeding, the number of living cells was determined semi-quantitatively by MTS assay.

2.5.4 ∣. Immuno-fluorescence imaging

Fluorescence images of MC3T3-E1 cells on the hydrogels were scoped at 4 days post-seeding. After being fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and permeabilized by 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min at room temperature, cells were blocked in 1% bovine serum albumin at 37°C for 30 min. In immunofluorescence, cells were incubated at 37°C with anti-vinculin-FITC antibody (1:50 in PBS, Sigma-Aldrich Co.) for 1 h, rhodamine–phalloidin (RP, 1:200 in PBS, Cytoskeleton Inc) for 1 h, and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to visualize cellular focal adhesion, cell cytoskeleton, and cellular nuclei, respectively. The stained MC3T3 cells were immediately viewed using the fluorescent microscope.

2.5.5 ∣. Cell differentiation

For osteogenic differentiation, media was changed for OM after being incubated with CM for 1 day. After being cultured for 12 days, the alkaline phosphatase (ALP) concentration released in the medium was determined by a QuantiChrome™ alkaline phosphatase assay kit (DALP-250, BioAssay Systems). After being cultured for 21 days, the osteocalcin (OCN) concentration released in the medium was quantified using the Mouse Osteocalcin Enzyme Immunoassay Kit (J64239, Alfa Aesar). The above results were normalized to the cell number of the corresponding well. The ALP activity and OCN content were reported as relative fold change as compared to the OPF treatment value as a control.

2.6 ∣. Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism 7 (La Jolla, CA) was used for statistical analysis. Normal distribution fitting was used to define the average size of BP. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine the differences between the groups, and further multiple comparisons were conducted using Tukey's honest significant difference test. A p-value of <.05 was considered to be significantly different.

3 ∣. RESULTS

3.1 ∣. Characterization of fabricated BP

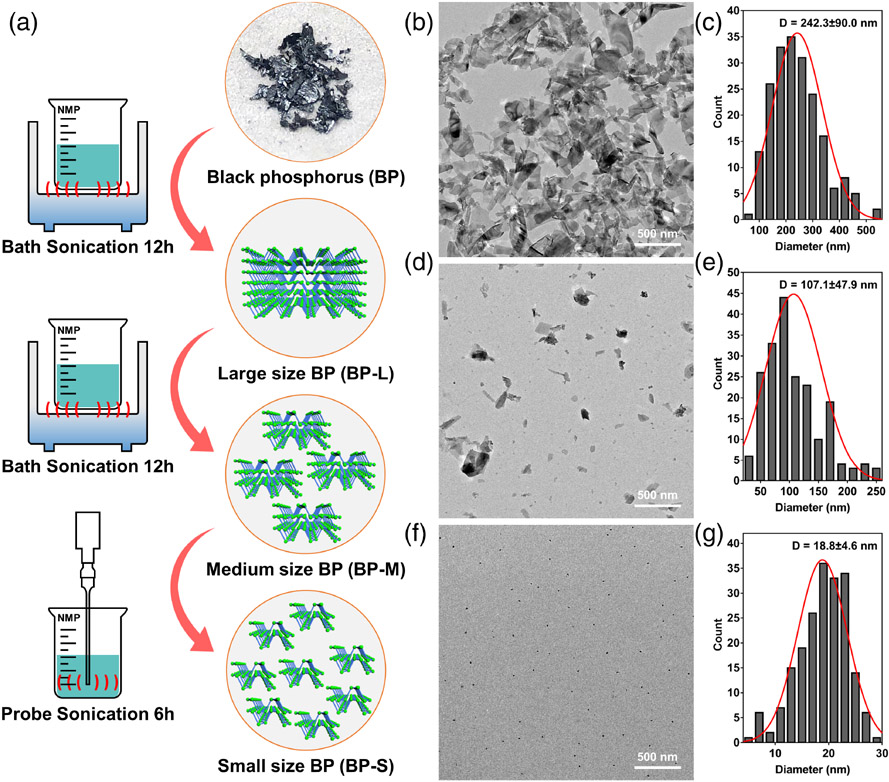

BP could be exfoliated into nano-scale materials of different sizes by controlling the time and mode of liquid exfoliation (Figure 1A). Figure S1 illustrated three types of BP aqueous solutions in the concentration of 1000 ppm, demonstrating different sedimentation velocities. Standing for 8 h, the BP-L solution was more transparent than the other two groups, and most of BP-L nanosheets had settled to the bottom after 48 h of settlement, showing the fastest sedimentation rate in the BP-L group. Between BP-M and BP-S groups, few differences could be detected in the images of 8 and 24 h; however, the difference in the color depth of the solutions became remarkable after 48 h of settlement, where the BP-S solution showed more homogeneous with a dark color, and the BP-M solution was more concentrated in the lower part. As a result, the larger size of BP corresponds to a faster sedimentation velocity, and the BP quantum dots could maintain a uniform distribution over a long period in an aqueous solution.

FIGURE 1.

(A) Schematic illustration of preparation strategy via liquid exfoliation method. (B) TEM image of BP-L and (C) corresponding quantitative diameter measurement of 200 BP nanosheets. (D) TEM image of BPM and (E) corresponding quantitative diameter measurement of 200 BP nanosheets. (F) TEM image of BP-S and (G) corresponding quantitative diameter measurement of 200 BP nanosheets. BP, black phosphorus; TEM, transmission electron microscopy

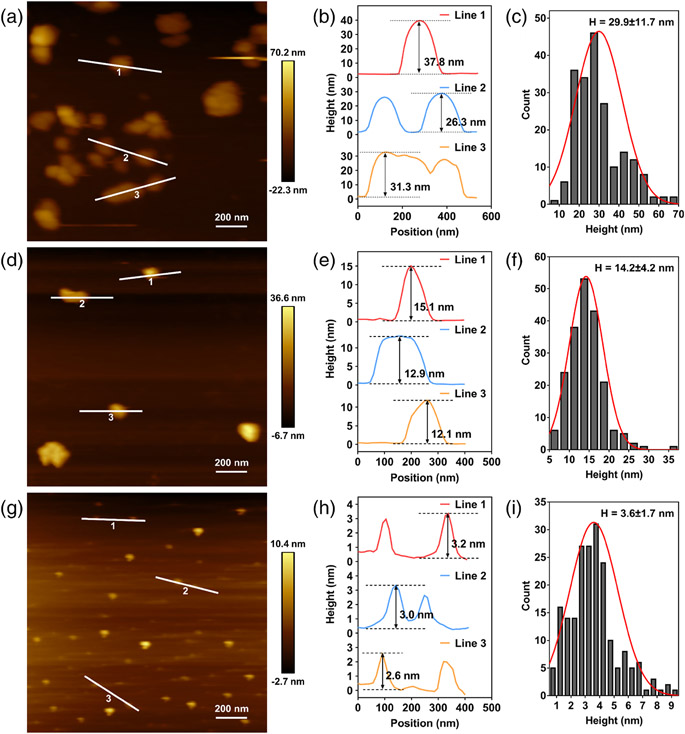

The actual sizes of three types of BP were confirmed by TEM and AFM. In the TEM images, BP-L nanosheets were clustered large particles, with the average diameter measured to be 242.3 ± 90.0 nm (Figure 1B,C). The size of BP-M is about half of BP-L, and the average value was shown to be 107.1 ± 47.9 nm (Figure 1D,E). BP-S appeared as distributed black dots, reaching the scale of quantum dots, with a diameter of 18.8 ± 4.6 nm (Figure 1F,G). Similarly, the thickness of BP nanosheets was calculated by AFM imaging. As a result, the layer height of BP-L (Figure 2A-C), BP-M (Figure 2D-F), and BP-S (Figure 2G-I) was about 29.9 ± 11.7, 14.2 ± 4.2, and 3.6 ± 1.7 nm, respectively.

FIGURE 2.

AFM image of highly-dispersed BP-L (A), BP-M (D), and BP-S (G). BP-L (B), BP-M (E), and BP-S (H) thickness measurement based on lines in (A), (D), and (G), respectively. Corresponding quantitative height measurement of 200 nanosheets in BP-L (C), BP-M (f), and BP-S (I). AFM, atomic force microscopy

3.2 ∣. Characterization of OPF@BP hydrogels

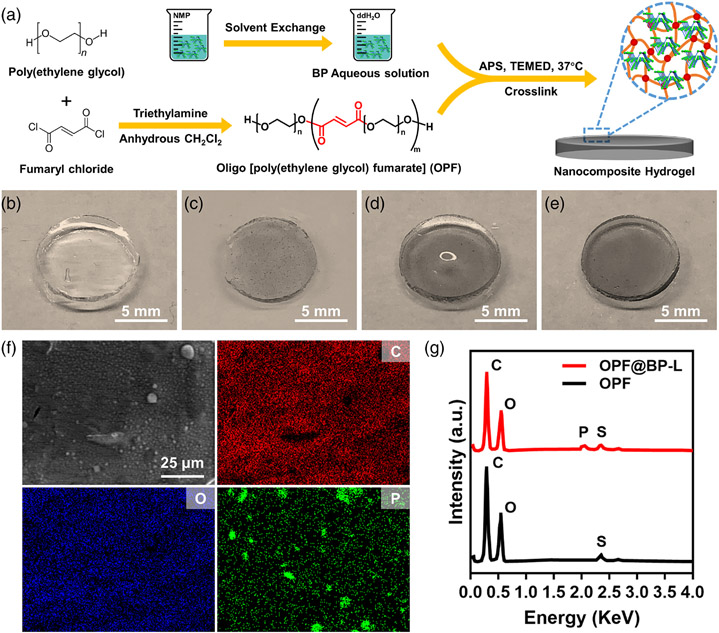

Four types of nanocomposite hydrogels were fabricated by integrating pre-synthesized OPF polymers and different BP aqueous solutions. In the gross images, the unmodified OPF hydrogel disc was completely transparent and colorless (Figure 3A), while, the other three groups exhibited varying degrees of gray with the addition of BP. BP-L scattered in the hydrogel with some visible black particles (Figure 3B), while BP-S hydrogel demonstrated a uniform grayscale which indicated an even distribution of the BP quantum dots in the hydrogel (Figure 3D).

FIGURE 3.

(A) Structure of OPF polymer and schematic illustration of the fabrication process of OPF@BP hydrogels. Gross view of OPF (B), OPF@BP-S (C), OPF@BP-M (D), and OPF@BP-S (E) hydrogel. (F) Element mappings of C, O, and P on OPF@BP-L hydrogel. (G) EDS results of OPF and OPF@BP-L hydrogel. EDS, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy; OPF, oligo[poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate]

The successful introduction of BP nanosheets into the synthesized hydrogel was confirmed by element mapping and EDS. As displayed in Figure 3F, OPF@BP hydrogel was rich in carbon (C) and oxygen (O) elements, both of which were the main components of the OPF network and distributed homogeneously in the hydrogel. Phosphorus (P) nanosheets were sparsely distributed in the hydrogel, indicating the area of BP nanosheets located. In the corresponding EDS results, peaks of carbon, oxygen, and sulfur (S) could be detected in the unmodified OPF sample, while a phosphorus peak could be spotted in other OPF@BP hydrogels. Under SEM imaging, the morphology of cross-linked OPF hydrogel was smooth (Figure S2a) and the introduction of BP had no obvious effect on the surface structure of the hydrogels (Figure S2b-d).

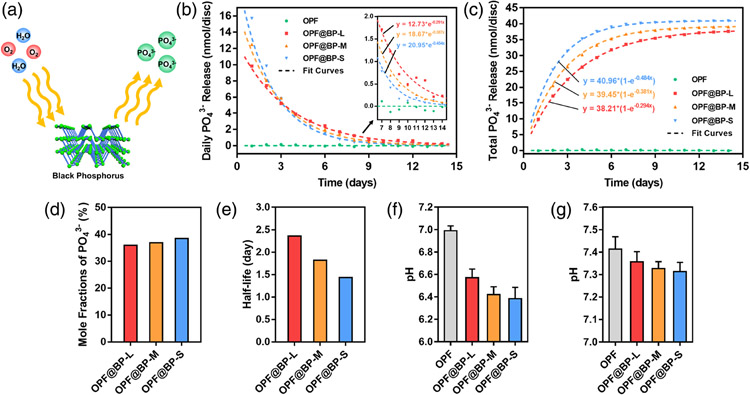

3.3 ∣. BP degradation and phosphate release

BP in the obtained nanocomposite hydrogels could degrade into phosphate gradually and continuously release to the surrounding solution (Figure 4A). The daily release of phosphate decreased exponentially with time (Figure 4B). The BP degradation of the OPF@BP-S group followed a more rapid style, as the release amount of phosphate of the OPF@BP-S group was about 1.6 times that of the OPF@BP-L group during the first day. However, the BP in the OPF@BP-L group degraded at a more subdued pace; thus, the daily phosphate release amount appeared the highest value in the OPF@BP-L group after day 4. The trend of degradation of OPF@BP-M group is between that of OPF@BP-S group and OPF@BP-L group. After 2 weeks, the daily releases of phosphate were negligible, suggesting almost complete degradation of BP. During the degradation process, the pH value in the surrounding environment is maintained within the physiological level (Figure 4F,G).

FIGURE 4.

(A) Schematic illustration of the degradation of BP when exposed to oxygen and water. (B) Daily and (C) cumulative phosphate release from OPF@BP hydrogels at 37°C (n = 1). (D) Mole conversion ratio of BP into phosphates in hydrogels (n = 1). (E) Half-lives of phosphate release from different hydrogels (n = 1). (F) pH value of solution after 3 days of degradation in ddH2O (baseline pH = 7.0, n = 3). (F) pH value of solution after 3 days of degradation in PBS (baseline pH = 7.4, n = 3). BP, black phosphorus

In the accumulation results, the resulting cumulative phosphate release of OPF@BP-L, OPF@BP-M, and OPF@BP-S followed the fitting equations of 38.21 * (1 − e−0.294t), 39.45(1 − e−0.381t), and 40.96(1 − e−0.484t), respectively (Figure 4C). OPF@BP-S group illustrated the fastest degradation rate and reached the plateau stage after 7 days, with about 40 nmol of phosphate released from each hydrogel disc. The plateau stage of the BP-M and BP-L groups reached after 10 and 14 days, respectively. Estimated by the size of each disc, the total content of BP in each hydrogel sample was calculated to be 105.97 nmol so that 38.65% of BP converted into phosphate in the BP-S group, 37.23% in the BP-M group, and 36.06% in the BP-S group (Figure 4D). The overall half-life of BP in hydrogels was 1.43, 1.82, and 2.36 days in OPF@BP-S, OPF@BP-M, and OPF@BP-L, respectively.

3.4 ∣. MC3T3 cell proliferation

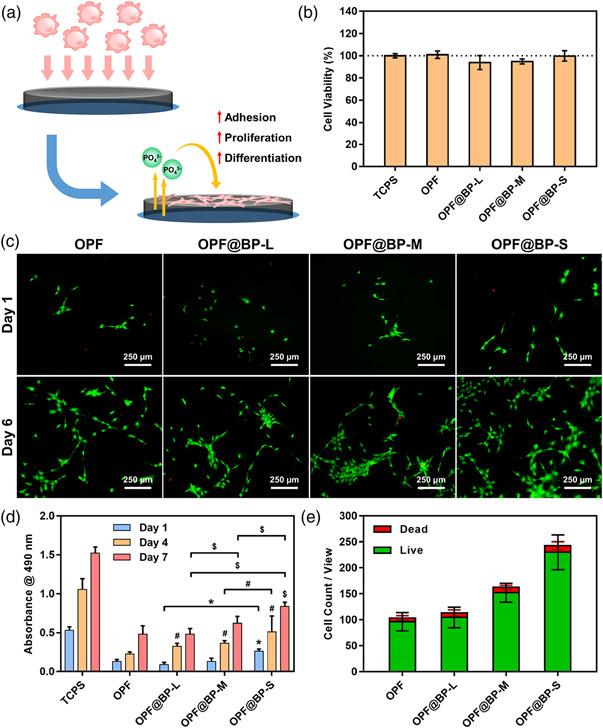

At first, the cytotoxicity of the hydrogel scaffolds was evaluated by cell culture in the leaching medium via transwell. After 4 days, the MTS assay demonstrated there was no significant difference among positive control and four hydrogel groups (Figure 5B), suggesting that the fabricated nanocomposite hydrogels do not release toxic substances and are thus biocompatible for implantation.

FIGURE 5.

(A) Schematic illustration of the cell behavior cultured on OPF@BP hydrogel. (B) Cell viability of MC3T3 cells culture with OPF@BP hydrogel in transwell for 4 days (n = 4). (C) Live/dead staining images of MC3T3 cells on OPF@BP hydrogels after 1 and 6 days post-seeding. (D) MTS absorbance of MC3T3 cells at 1, 4, and 7 days post-seeding on the four types of hydrogels (n = 4, * # $: p < .05 compared to OPF group or between the two specified groups, * for day 1, # for day 4, and $ for day 7). TCPS served as the positive control. (E) Cell counting results in each view in the live/dead staining images (five different views). OPF, oligo[poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate]

The distribution and proliferation of MC3T3 cells seeded on hydrogel were further determined by live/dead assay. As demonstrated in Figure 5C, the presence of living cells on all four types of hydrogel was confirmed at 1-day post-seeding and the OPF@BP-S hydrogels had subtly higher cell growth when compared to the other three groups. After 6 days of culture, more cells were observed in all groups and there was a clear trend that the trend of proliferation increased with the addition of BP as well as the reduction of BP size (Figure 5C). In the quantitative results, the number of living cells in a single microscopic field on OPF@BP-M hydrogels was statistically higher than that of OPF and OPF@BP-L hydrogels (Figure 5D). For OPF@BP-S hydrogels, a broader cell distribution was observed, with about 2.5 times the number of cells on pure OPF hydrogels. There was no significant difference in the proportion of dead cells among the four groups.

The same trend was also proved by the MTS results. After 7 days post-seeding, cell viability increased gradually as time went on in all groups. In four hydrogel groups, OPF and OPF@BP-S exhibited the lowest and highest cell viability, respectively; especially at 7 days post-seeding, the OPF@BP-S group showed a significantly higher OD value when compared with the other three groups. It was indicated that the hydrogel with the small size of BP quantum dots has the greatest effect on osteogenesis, and can effectively promote cell adhesion and growth.

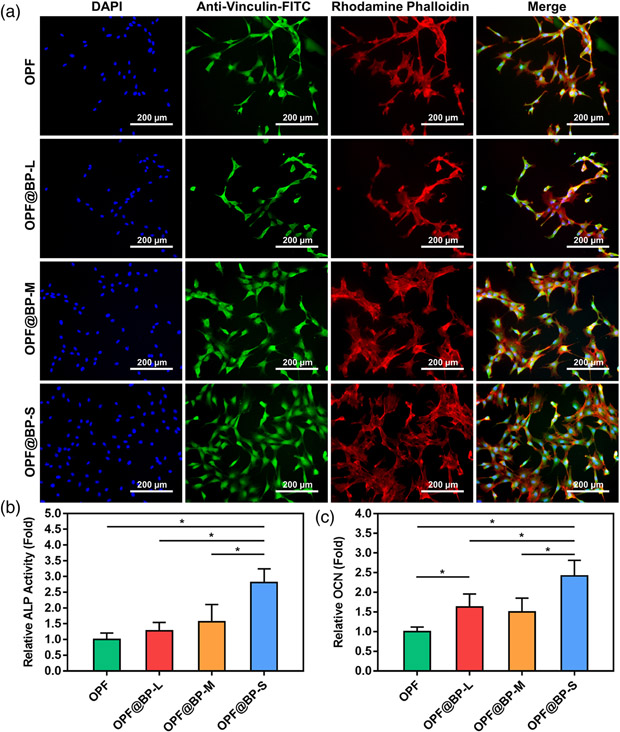

At 4 days post-seeding, immunofluorescence images of the MC3T3 cells growing on the hydrogels were viewed as presented in Figure 6A, in which cell nuclei stained blue by DAPI, vinculin stained green by anti-vinculin-FITC, and F-actin was stained red by rhodamine–phalloidin. The favor of BP quantum dots to osteogenesis could be observed not only in the significantly higher MC3T3 cells quantity attached on hydrogels but also in the significantly more development of vinculin and F-actin (Figure 6A).

FIGURE 6.

(A) Immunofluorescence images of MC3T3 cells on four types of hydrogels after 4 days of culture. F-actin was stained red by rhodamine–phalloidin, vinculin stained green by anti-vinculin-FITC, and cell nuclei stained blue by DAPI. (B) Relative ALP activity (fold change) of MC3T3 cells on four types of hydrogels after 12 days of culture (n = 5, *p < .05). (C) Relative OCN secretion (fold change) of MC3T3 cells on four types of hydrogels after 21 days of culture (n = 5, *p < .05). ALP, alkaline phosphatase; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; OCN, osteocalcin

As shown in Figure 6B, the expression of ALP increased in varying degrees after the addition of BP, demonstrating a significantly higher activity in the OPF@BP-S group when compared with the other three groups. Similarly, the expressions of OCN in OPF@BP-L and OPF@BP-S groups were significantly higher than that in the OPF group, and BP-S displayed the most obvious promoting effect on cellular differentiation.

4 ∣. DISCUSSION

BP bulks could be processed into nanosheets of varying sizes. The BP nanosheets with lateral sizes of about 10 nm are defined as BP quantum dots, which were initially produced in 2015.12 Zhang et al.12 prepared BP quantum dots with a lateral size of 4.9 ± 1.6 nm and thickness of 1.9 ± 0.9 nm through a facile top-down approach, and indicated their intrinsic advantages, subsequently stirring the enthusiasm of research related to BP quantum dots. In recent years, different methods including household kitchen blender,21 ice-bath sonication,12 and ultrasound probe sonication22 were used to prepare BP quantum dots, and the lateral size of BP quantum dots was varied from 2.2 to 4.9 nm. In our study, three types of BP nanosheets with different sizes were prepared via a combined ultrasonic strategy. As a result, the lateral size of BP-L and BP-M were 242.3 ± 90.0 and 107.1 ± 47.9 nm, respectively. As for BP-S, the lateral size of 18.8 ± 4.6 nm met the defined criterion of BP quantum dots.

In addition to the unique structural properties, conductivity, and biocompatibility, BP has the potential for bone tissue engineering applications due to its osteogenic capacity, which was mainly attributed to its degradability. Applied in the nanocomposite hydrogel system, BP was biodegradable and easy to be oxidized gradually when exposed to oxygen and aqueous solution,23 spontaneously producing a series of intermediates, such as phosphoric acid, phosphorous acid, and hypophosphorous acid.24,25 Among these degradation products, phosphate, as the primary component of phosphoric acid, plays an important role in osteogenesis, promoting the synthesis of adenosine triphosphate, nucleic acid, and cell membranes,8 concurrently favoring bone mineralization.26

An exponential style was illustrated in the degradation kinetics of BP loaded in the nanocomposite hydrogels. In the first 3 days, OPF@BP-L hydrogel released the largest amount of phosphate, and after that, the maximum value occurred in the OPF@BP-S group. In conclusion, the size of BP had a significant effect on its degradation behavior, as the smaller size of BP degraded faster and produced more phosphate. The smaller BP nanosheets have a larger specific surface area leading to more exposure to the ambient environment. Since the degradation of BP requires contact with oxygen and water, we infer that a larger surface area is the cause of faster degradation. After 12 days, the phosphate release in each group was negligible, indicating most of BP degraded and the accumulative phosphate release reached a plateau stage.

Hydrogels have been developed for several biomedical applications due to their biocompatibility, dynamic water absorption, and ability to provide a growth environment for living cells. OPF hydrogel has previously been shown by our group to support both cartilage tissue and nerve regeneration. In the current study, OPF hydrogels acted as cell scaffolds, BP carriers, BP degradation controllers, and liquid exchange platforms. The introduction of phosphorus into the OPF polymer network with potential phosphate release may therefore modulate the osteogenic capability of the hydrogels. As testified in our previous study, the supplementation of BP nanosheets was instrumental in the attachment, proliferation, and differentiation of pre-osteoblast cultured on nanocomposite hydrogels, indicating the application prospect in bone tissue engineering. With the understanding of BP quantum dots deepening, it is worthy of our further study whether BP nanosheets with different morphology have varying biological characteristics. Size effect on the cytocompatibility of BP was detected by Zhang et al.,14 illustrating BP with the larger lateral size and thickness has the higher cytotoxicity with the potential mechanisms related to intracellular reactive oxygen species and cell membrane integrity. In our study, we focused on the size-effect on osteogenesis, which has not been reported by other research yet.

We performed in vitro study by culturing a pre-osteoblast MC3T3 cell line derived from mouse calvaria27 on hydrogels to evaluate the osteogenic capability of each formulation. As revealed consistently in the MTS test and live/dead stain, preferable cellular attachment and proliferation were displayed with the addition of BP into hydrogels, which is in line with the previous study.9 The best cell behavior was detected in the OPF@BP-S group, indicating that the BP quantum dots may be most conducive to cell proliferation among BP nanosheets of different sizes.

Vinculin is a cellular adhesion-associated cytoskeletal protein,28 and F-actin is a key protein for cellular mobility and contraction.29,30 Thus, the development of these proteins suggested positive adhesion, distribution, and proliferation of MC3T3 cells on the functionalized hydrogels. Therefore, hydrogels loaded with BP, especially BP quantum dots, had great improvement in cell compatibility and would be enormously beneficial for bone tissue engineering.

Osteogenic differentiation behavior was also regulated by the addition of BP, as confirmed by quantifying the activity of two typical osteogenic differentiation markers, ALP and OCN, during the cell culture. ALP and OCN activity are highly sensitive to osteogenic differentiation, which could be homogeneously and linearly measured by commercial ELISA kits.31 Both markers were measured at the critical period of expression, like 12 days post-seeding for ALP and 21 days post-seeding for OCN. Consequently, both the relative ALP activity and the OCN secretion were heightened in the group with BP addition, especially when BP quantum dots were enrolled, demonstrating the facilitation of BP quantum dots to the differentiation of preosteoblasts when applied in the nanocomposite hydrogel system.

5 ∣. CONCLUSION

BP could be processed into nanosheets with varying size via different exfoliation strategy and BP quantum dots was obtained by the combination of bath-sonication and probe-sonication. In the nanocomposite hydrogel system, the degradation kinetics of embedded BP was controlled, at an exponential rate, increasing with the decrease of the size of the nanosheets. Consequent phosphorus release was in favor of the osteogenic capability of nanocomposite hydrogel, in which size-effect of the BP nanosheets embedded obvious, as the BP in the smaller size displayed further improvement in the proliferation and differentiation of pre-osteoblast cells. In conclusion, BP nanosheets, especially BP quantum dots, enhanced MC3T3 cell behaviors including spreading, distribution, proliferation, and differentiation on the OPF hydrogels. The nanocomposite hydrogel system could potentially find application in the restoration of bone defects.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant R01 AR 75037.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of the article at the publisher's website.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Liu H, Neal AT, Zhu Z, et al. Phosphorene: an unexplored 2D semiconductor with a high hole mobility. ACS Nano. 2014;8(4):4033–4041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li L, Yu Y, Ye GJ, et al. Black phosphorus field-effect transistors. Nat Nanotechnol. 2014;9(5):372–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim J, Baik SS, Ryu SH, et al. 2D MATERIALS. Observation of tunable band gap and anisotropic dirac semimetal state in black phosphorus. Science. 2015;349(6249):723–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Batmunkh M, Bat-Erdene M, Shapter JG. Phosphorene and phosphorene-based materials – prospects for future applications. Adv Mater. 2016;28(39):8586–8617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anju S, Ashtami J, Mohanan PV. Black phosphorus, a prospective graphene substitute for biomedical applications. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2019;97:978–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang H, Yu XF. Few-layered black phosphorus: from fabrication and customization to biomedical applications. Small. 2018;14(6):1702830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Childers DL, Corman J, Edwards M, Elser JJ. Sustainability challenges of phosphorus and food: solutions from closing the human phosphorus cycle. Bioscience. 2011;61(2):117–124. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pasek M. A role for phosphorus redox in emerging and modern biochemistry. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2019;49:53–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu H, Liu X, George MN, et al. Black phosphorus incorporation modulates nanocomposite hydrogel properties and subsequent MC3T3 cell attachment, proliferation, and differentiation. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2021;109(9):1633–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li L, Liu X, Gaihre B, Li Y, Lu L. Mesenchymal stem cell spheroids incorporated with collagen and black phosphorus promote osteogenesis of biodegradable hydrogels. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2021;121:111812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Latiff NM, Teo WZ, Sofer Z, Fisher AC, Pumera M. The cytotoxicity of layered black phosphorus. Chemistry. 2015;21(40):13991–13995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang X, Xie H, Liu Z, et al. Black phosphorus quantum dots. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54(12):3653–3657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker SN, Baker GA. Luminescent carbon nanodots: emergent nanolights. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49(38):6726–6744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang X, Zhang Z, Zhang S, et al. Size effect on the cytotoxicity of layered black phosphorus and underlying mechanisms. Small. 2013;13 (32):1701210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dadsetan M, Giuliani M, Wanivenhaus F, Brett Runge M, Charlesworth JE, Yaszemski MJ. Incorporation of phosphate group modulates bone cell attachment and differentiation on oligo(polyethylene glycol) fumarate hydrogel. Acta Biomater. 2012;8(4):1430–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dadsetan M, Knight AM, Lu L, Windebank AJ, Yaszemski MJ. Stimulation of neurite outgrowth using positively charged hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2009;30(23–24):3874–3881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dadsetan M, Szatkowski JP, Yaszemski MJ, Lu L. Characterization of photo-cross-linked oligo[poly(ethylene glycol) fumarate] hydrogels for cartilage tissue engineering. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8(5):1702–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu H, Li Z, Xie H, et al. Different-sized black phosphorus nanosheets with good cytocompatibility and high photothermal performance. RSC Adv. 2017;7(24):14618–14624. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu X, Miller AL 2nd, Park S, et al. Functionalized carbon nanotube and graphene oxide embedded electrically conductive hydrogel synergistically stimulates nerve cell differentiation. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(17):14677–14690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dadsetan M, Hefferan TE, Szatkowski JP, et al. Effect of hydrogel porosity on marrow stromal cell phenotypic expression. Biomaterials. 2008;29(14):2193–2202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu C, Xu F, Zhang L, et al. Ultrafast preparation of black phosphorus quantum dots for efficient humidity sensing. Chemistry. 2016;22(22): 7357–7362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun Z, Xie H, Tang S, et al. Ultrasmall black phosphorus quantum dots: synthesis and use as Photothermal agents. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54(39):11526–11530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang H, Yang X, Shao W, et al. Ultrathin black phosphorus nanosheets for efficient singlet oxygen generation. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137(35):11376–11382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang T, Wan Y, Xie H, et al. Degradation chemistry and stabilization of exfoliated few-layer black phosphorus in water. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140(24):7561–7567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plutnar J, Sofer Z, Pumera M. Products of degradation of black phosphorus in protic solvents. ACS Nano. 2018;12(8):8390–8396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LeGeros RZ. Calcium phosphate-based osteoinductive materials. Chem Rev. 2008;108(11):4742–4753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Czekanska EM, Stoddart MJ, Richards RG, Hayes JS. In search of an osteoblast cell model for in vitro research. Eur Cell Mater. 2012;24: 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geiger B, Spatz JP, Bershadsky AD. Environmental sensing through focal adhesions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(1):21–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doherty GJ, McMahon HT. Mediation, modulation, and consequences of membrane-cytoskeleton interactions. Annu Rev Biophys. 2008;37:65–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shawky JH, Balakrishnan UL, Stuckenholz C, Davidson LA. Multiscale analysis of architecture, cell size and the cell cortex reveals cortical F-Actin density and composition are major contributors to mechanical properties during convergent extension. Development. 2018;145(19): dev161281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin LY, Dong YM, Wu XM, Cao GX, Wang GL. Versatile and amplified biosensing through enzymatic cascade reaction by coupling alkaline phosphatase in situ generation of photoresponsive nanozyme. Anal Chem. 2015;87(20):10429–10436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.