Abstract

Vaccines are among the safest and most effective primary prevention measures. Thanks to the synergistic global efforts of research institutions, pharmaceutical companies and national health services, COVID-19 vaccination campaigns were successfully rolled out less than a year after the start of the pandemic. While the unprecedented speed of development and approval of COVID-19 vaccines has been applauded as a public health success story, it also spurred considerable controversy and hesitancy even amongst individuals that did not previously hold anti-vaccination stances. This study aimed to compare pre- and post-pandemic vaccine confidence trends in different demographic groups by analysing the outcomes of two online surveys run respectively in November 2019 and January 2022 involving a total of 1009 participants.

Non-parametric tests highlighted a statistically significant decline in vaccine confidence in the 2022 cohort compared to the 2019 cohort, with median Vaccine Confidence Score dropping from 22 to 20 and 23.8% of participants reporting that their confidence in vaccines had declined since the onset of the pandemic. While the majority of internal trends were comparable between the two surveys with regards to gender, graduate status and religious belief, vaccine confidence patterns showed considerable alterations with regards to age and ethnicity. Middle-aged participants were considerably more hesitant than younger groups in the 2019 cohort, however this was not the case in the 2022 survey. In both surveys White participants showed significantly higher vaccine confidence than those from Black backgrounds; in the 2022 cohort, unlike the pre-pandemic group, Asian participants showed significantly lower confidence than White ones.

This study suggests that paradoxically, despite the success of COVID-19 vaccination campaigns, vaccine confidence has significantly declined since the onset of the pandemic; the comparison of a pre- and post-pandemic cohort sheds light on the differential effect that the pandemic had on vaccine confidence in different demographic groups.

Keywords: Vaccine confidence, Vaccine hesitancy, COVID-19, Demographics, Survey

1. Introduction

Vaccination is widely considered to be one of the safest and most effective primary health care measures. The World Health Organization (WHO) aptly recognises that “Immunization is a global health and development success story, saving millions of lives every year” [1]. This is far from being an overstated claim, as immunisation campaigns have come a long way since the early days of variolation and inoculation. Their success stories include (but are not limited to) a dramatic reduction in the worldwide incidence of typhus, cholera, plague, tuberculosis, diphtheria and pertussis in the first half of the 20th century, the near elimination of polio, measles, mumps and rubella in the following decades, and the global eradication of smallpox in 1980 [2]. More recently, HPV youth vaccination campaigns in the 2000s and 2010s resulted in a substantial drop in cervical cancer incidence, and indeed an unprecedented global effort led to the record-breaking development of safe and effective vaccines against SARS‑CoV‑2 within months of the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic [3], [4].

Despite overwhelming evidence supporting its importance as a key primary prevention measure, immunisation has been the object of controversy and vocal opposition ever since its inception. While vaccine hesitancy and refusal are often erroneously considered a direct consequence of the publication of Wakefield’s infamous article on the Lancet in 1998 and the subsequent MMR controversy, their origins can be traced back to the early days of variolation, even before the administration of the first vaccine by Edward Jenner in 1796 [5], [6], [7]. The delay and refusal of life-saving vaccines has frequently resulted in the vaccination coverage falling below their herd immunity threshold leading to local outbreaks and the re-emergence of vaccine-preventable diseases (VPD), prompting the WHO to identify vaccine hesitancy as one of the top 10 biggest threats to modern global health [8], [9], [10].

The Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) was established in 1999 by the WHO as the principal advisory group for vaccines and immunisation. Since its foundation, SAGE has been investigating the determinants of vaccine hesitancy to support WHO, national governments and non-governmental organisations in their policy-making process. In 2011, SAGE proposed the 3Cs Model as a widely applicable framework to model the determinants of vaccine hesitancy [11]. The 3Cs Model identifies Confidence, Complacency and Convenience as the three overarching categories in which the key causes of vaccine hesitancy can be classified. In brief, Confidence is the trust in vaccines themselves, in the healthcare system that administers them, and in the policy-makers that promote or mandate them. Complacency refers to the perception that the risks associated with specific VPDs are too low to justify the hassle and potential side effects of the vaccinations. It is worth highlighting that complacency often arises for transmissible diseases (e.g. measles) the incidence and severity of which are considered low as a direct consequence of the success of their respective vaccination campaigns. Convenience refers to the availability, affordability, and accessibility of vaccination services, as well as the linguistic and health literacy required to access the relative information. In 2014, building upon the 3Cs model, SAGE developed the Vaccine Hesitancy Determinants Matrix as a framework to categorise the determinants of vaccine hesitancy with a higher level of granularity [12]. In this model, the factors that determine vaccine hesitancy are more explicitly laid out and grouped in three categories, namely contextual influences, individual and group influences, and vaccine/vaccination-specific influences. Since their publication, the SAGE frameworks have supported national health services and policy-makers worldwide in the promotion of vaccination campaigns, and have recently been implemented to model hesitancy and refusal of COVID-19 vaccines [13].

At the time this paper is being written, 11.9 billion doses of COVID-19 vaccine have been administered worldwide, corresponding to 61.2% of the global population being fully vaccinated, albeit with wide variation in vaccination rates between developing and developed countries [14]. Thanks to unprecedented global investments and the combined efforts of research institutions and pharmaceutical companies, the development of the first COVID-19 vaccines was announced within a few months of the WHO declaring COVID-19 a global pandemic in March 2020; after approval by national and international regulatory bodies for emergency use, the first vaccine doses were administered before the end of 2020 [15].

While the rapid development and administration of COVID-19 vaccines are widely considered an extraordinary public health accomplishment, they also spurred considerable controversy and opposition [16]. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy is largely underpinned by similar factors as the hesitancy towards other types of vaccines traditionally modelled via the SAGE 3Cs framework [13]. While convenience and complacency certainly play a non-negligible role in determining COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, specific factors that fall under the “confidence” category appear to be preponderant. In particular, two key determinants of mistrust towards COVID-19 vaccination campaigns are the belief in conspiracy theories (e.g. that the vaccines contain mind-control microchips or cause infertility) and the notion that COVID-19 vaccines (especially RNA-based formulations) have been approved too quickly for them to have been adequately safety-checked, the latter often presenting itself in individuals that are not hesitant towards more established vaccinations [17], [18].

Despite COVID-19 vaccination campaigns having led to a sharp decline in infections, hospitalisations and deaths, a paper recently published in The Lancet suggested that “willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 has declined globally between the early months of the pandemic and December, 2020” [19]. This evidence poses the paradoxical question of whether public vaccine confidence has fallen below the pre-pandemic levels despite the successful implementation and outcomes of COVID-19 vaccination campaigns worldwide. The present study aims to address this interrogative by comparing vaccine confidence between two cross-sectional surveys carried out with similar modalities in November/December 2019 and January/February 2022 respectively. For both cohorts, Vaccine Confidence Scores were assessed in relation to demographic grouping variables to evaluate whether any observed changes in vaccine confidence are statistically associated to specific demographics.

2. Methods

2.1. Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the University of Portsmouth Research Ethics Policy and with the Helsinki declaration for research involving human subjects. Ethical approval (code BIOL-ETHICS#002-2019 and BIOL-ETHICS #022-2021 respectively) was gained prior to the distribution of each survey. Informed consent was ensured using a disclaimer provided at the start of each survey to inform participants of the modalities and purposes of the study, as well as of its anonymous nature and their right to withdraw at any point or leave any question unanswered. Although some personal information was collected about the socio-demographic status of participants (e.g. gender, ethnicity, religion, etc.), no information was collected that would allow the identification of individual participants (e.g. name, date of birth, e-mail or physical address). Individuals under the age of 18 and those who did not provide consent were excluded from the study. All data were handled and stored in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

2.2. Surveys

Two anonymous online surveys were run to investigate the public perspectives on the practice of vaccination and the factors that might underpin hesitancy and refusal. Both surveys were created and administered using Google Forms; participants were recruited via snowball sampling by sharing the survey link on multiple social media platforms (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat) and via e-mail to suitable contacts in the investigators’ mailing lists. The first survey was distributed in November and December 2019, at a time when the first COVID-19 cases were being identified in China, prior to any cases being detected in Europe and to the pandemic status being declared. The second survey was distributed in January and February 2022. The 2019 and 2022 surveys consisted of 28 and 19 questions respectively. The questionnaires used in the surveys were adapted from the WHO SAGE Vaccine Hesitancy Scale to better reflect the present study’s focus on adult vaccination in addition to childhood vaccination [20]. Crucially, 10 questions analysed in this study (Table 1 ) were the same across the two surveys, allowing responses to be compared between the two cohorts. 5 of the 10 shared questions regarded the demographic information on the participants, while the other 5 were used for the calculations of the Vaccine Confidence Score (see next section for definition). Two questions specifically focused on the COVID-19 pandemic, and where therefore only included in the 2022 survey.

Table 1.

Questions used in the study. The questions marked with a single asterisk (*) were used in the calculation of the Vaccine Confidence Score (VCS). Questions relative to the COVID-19 pandemic (marked with **) were only used in the 2022 survey.

| Personal information (multiple choice questions) |

| What is your age? |

| What gender do you identify as? |

| What is your highest academic qualification? |

| What is your ethnic group? |

| What is your religion/spiritual belief? |

| **How many doses of the COVID-19 vaccines have you received? |

| Attitude on vaccinations (Likert-type questions) |

| *Vaccines are safe. |

| *I think vaccines should be a compulsory practice. |

| *My healthcare provider (for example my GP) has mine and/or my child’s best interests at heart. |

| *I believe if I get vaccinated it would benefit the wellbeing of others. |

| *Vaccines are a necessity for our health and wellbeing. |

| **Since the COVID-19 pandemic, my confidence in vaccines has (increased/stayed the same/decreased) |

2.3. Statistical analysis

The Vaccine Confidence Score (VCS) was calculated as previously described [21] by converting the answers to 5 Likert-type questions to a numerical value (1 point for Strongly Disagree to 5 points for Strongly Agree), and therefore ranges from 5 (lowest confidence) to 25 (highest confidence). Participants who did not answer all 5 questions were excluded from the calculation of the VCS. Statistical analysis was carried out using the IBM SPSS 28 software. Non-parametric tests were chosen due to the categorical nature of the data collected in the surveys. Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare median VCS between different groups of participants within each cohort. For comparisons where a statistically significant difference was highlighted, Dunn’s pairwise post-hoc tests were performed to identify between which groups the significant differences lied. The significance values were adjusted using the Bonferroni correction to reduce the likelihood of type I errors associated with multiple simultaneous pairwise comparisons. A significance cut off of p ≤ 0.05 was used for all statistical tests.

3. Results

739 individuals participated in the survey in 2019 and 270 in 2022, amounting to a total of 1009 participants. The demographic characteristics of both cohorts are shown in the supplementary information, Table SI1 and SI2 respectively. While there were some deviations between the two groups as can be expected in the case of non-random sampling, both cohorts showed a majority of female, white, young adults.

As shown in Fig. 1 , median vaccine confidence score showed a significant decline (χ2 = 63.512; df = 1; p = 1.5x10−15) from 22 in 2019 to 20 in 2022.

Fig. 1.

Overall vaccine confidence in the 2019 (n = 739) and 2022 (n = 270) cohorts.

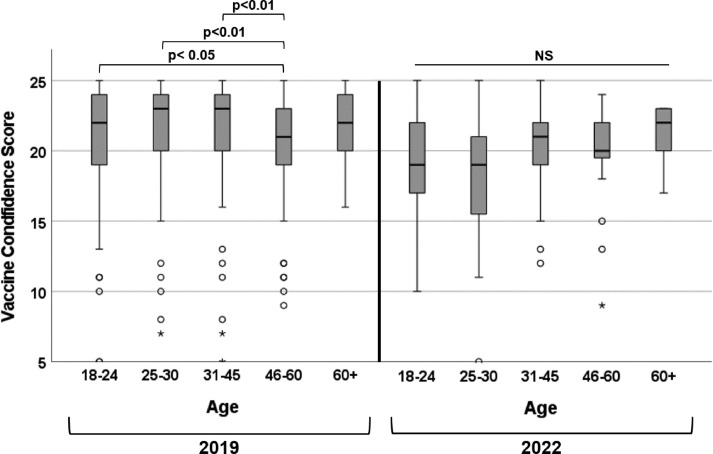

A significant difference (χ2 = 18.321; df = 4; p = 0.001) was found in the VCS between different age groups in the 2019 cohort (Fig. 2 ). Post-hoc pairwise analysis revealed significant differences between the 46–60 age group and all the lower age groups (18–24, p = 0.029; 25–30, p = 0.007; 31–45, p = 0.001) but not with the 60+ age group. No significant difference (χ2 = 4.916; df = 4; p = 0.296) in VCS between age groups was observed in the 2022 cohort.

Fig. 2.

Association between participants’ age and vaccine confidence in 2019 (left) and 2022 (right).

As shown in Fig. 3 , no significant difference in median VCS was observed by gender identity in the 2019 cohort (χ2 = 0.388; df = 2; p = 0.824) and in the 2022 cohort (χ2 = 2.237; df = 2; p = 0.327).

Fig. 3.

Association between participants’ gender and vaccine confidence in 2019 (left) and 2022 (right).

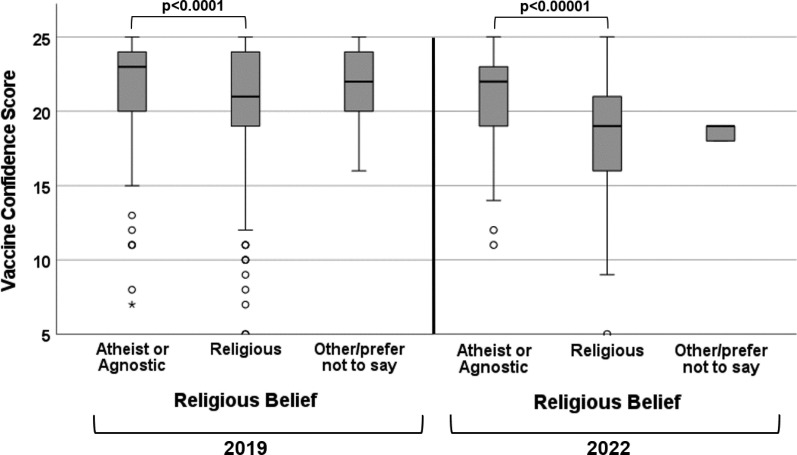

Significant differences in median VCS were observed (Fig. 4 ) with regards to participants’ religious beliefs in both 2019 (χ2 = 20.374; df = 2; p = 0.00004) and 2022 (χ2 = 23.019; df = 2; p = 0.00001). Atheists and agnostic participants showed significantly higher VCS than their religious peers; the difference had a higher significance level in 2022 (p = 0.000008) than in 2019 (p = 0.00002). A considerable variation in median VCS was observed in participants who responded “Other/prefer not to say” between 2019 and 2022. However, as participants who provided these responses were very limited in number in both cohorts, this observation holds no statistical relevance.

Fig. 4.

Association between participants’ religious beliefs and vaccine confidence in 2019 (left) and 2022 (right).

In both cohorts participants with a university degree had higher median VCS than those without (Fig. 5 ); the difference was statistically significant in 2019 (χ2 = 7.813; df = 2; p = 0.02) but not in 2022 (χ2 = 2.799; df = 2; p = 0.247).

Fig. 5.

Association between participants’ graduate status and vaccine confidence in 2019 (left) and 2022 (right).

As shown in Fig. 6 , Kruskal-Wallis tests revealed that participants from different ethnic backgrounds had significantly different median VCS both in 2019 (χ2 = 56.839; df = 4; p = 1.3x10−11) and in 2022 (χ2 = 32.543; df = 4; p = 0.000001). In the pre-pandemic cohort Black participants had significantly lower VCS than White (p = 1.8x10−12) and, to a lesser extent, Mixed/Multiple ethnicity ones (p = 0.015). In the post-pandemic cohort, both Black participants (p = 0.0008) and Asian participants (p = 0.0002) had lower median VCS than those from White ethnicities.

Fig. 6.

Association between participants’ ethnicity and vaccine confidence in 2019 (left) and 2022 (right).

A significant association (χ2 = 64.987; df = 3; p = 5.05x10−14) was observed between the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses received by participants and their vaccine confidence score (Fig. 7 ). Median VCS ranged from 15 for individuals who did not receive any vaccine doses to 21 for those who received three doses. Post-hoc analysis showed that participants who received three doses had significantly higher median VCS than those who received two (p = 0.016), one (p = 0.009) and zero (p = 8.18x10−13) doses. Participants who received two doses had significantly (p = 3x10−6) higher median VCS than those who received zero doses, however the differences between participants with zero and one doses and between those with one and two doses were not significant.

Fig. 7.

Association between the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses received by participants in the 2022 cohort and their vaccine confidence.

When participants in the 2022 cohort were asked to self-assess their vaccine confidence since the COVID-19 pandemic, 54.6% reported no change in confidence, 23.8% a decrease in confidence, and 21.6% an increase in confidence (Fig. 8 ).

Fig. 8.

Self-reported change in vaccine confidence since the COVID-19 pandemic within the 2022 cohort.

4. Discussion

The comparison of two convenience samples surveyed in 2019 and 2022 highlighted that, while the internal trends were relatively consistent within each cohort, there was a decline in vaccine confidence scores following the COVID-19 pandemic irrespective of the participants’ gender, age, graduate status, ethnicity and religious belief. Despite abundant epidemiological evidence of the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines, only approximately 1 in 5 participants of the 2022 cohort self-assessed their vaccine confidence as having increased since the pandemic; the majority of participants reported that their confidence remained unchanged or even decreased. These observations are compatible with studies carried out in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic indicating that, in contrast to previous evidence that the perceived threat from a disease should improve public vaccine confidence, willingness to receive a COVID-19 vaccine started decreasing even before the vaccines were developed [19], [22].

In the present study, the most noticeable change in attitude between 2019 and 2022 was that, while pre-pandemic the 46–60 years old group was considerably less vaccine-confident than all other age groups, this was not the case in the post-pandemic cohort. In fact, while none of the differences observed between age groups in the 2022 cohort were statistically significant (which is arguably an important finding in its own right, in agreement with a survey carried out at the onset of the Omicron wave), median VCS appeared to increase with age from 19 in participants under 30 years old to 22 in those over 60 years old [23]. This observation is compatible with previous findings of a survey carried out during the Delta wave, indicating that “younger populations had less willingness to receive vaccinations” [24]. This trend might also reflect the disproportionate severity of COVID-19 in older patients, which may have prompted in elderly and vulnerable participants a higher perception of the infection risk, and therefore a higher reliance in preventive measures [25], [26].

In both surveys, no statistical association was observed between gender identity and vaccine confidence. While this observation is in apparent disagreement with previous reports of lower COVID-19 vaccination intentions in women [27], [28], it supports the results of other studies reporting no significant association between gender and vaccine hesitancy [29]. Abundant evidence indicates that inter-sectional determinants might have a differential (and therefore confounding) impact on different demographics surveyed in individual studies [30], [31].

The finding that non-religious people in the 2019 cohort were significantly less vaccine-confident than those who held religious beliefs was confirmed in the 2022 cohort. The extent of the difference appeared to have increased since the COVID-19 pandemic: non-religious participants had a median VCS higher by 2 points than religious ones in 2019, and by 3 points in 2022; the p-value of the difference was an order of magnitude higher in 2022 compared to 2019. These findings corroborate previous pre- and post-pandemic reports that adherence to religious beliefs is frequently associated with vaccine hesitancy [32], [33].

In both cohorts, participants with a university degree had a VCS higher by 1 point than those without a degree. The difference was statistically significant in the 2019 but not in the 2022 survey, although this might be attributable to the fact that the p-value was close to the 0.05 threshold in the 2019 cohort and therefore the statistical significance might have been lost due to the smaller sample size and therefore statistical power in the 2022 cohort. This borderline behaviour is consistent with previous conflicting evidence with regards to the direction (or even existence) of any association between academic qualifications and vaccine hesitancy [34], [35], [36].

The two surveys highlighted very similar trends with regards to the association between ethnicity and vaccine confidence: in both cohorts, participants from White and Mixed/Multiple backgrounds showed the highest levels of vaccine confidence, followed by participants from Asian backgrounds. Participants from Black ethnic backgrounds showed in both cases the lowest levels of vaccine confidence; the difference was statistically significant with respect to White participants in both surveys, and to those with Mixed/Multiple ethnicities in the 2019 survey. Asian participants were in both surveys less confident than White ones, however the difference was only statistically significant in the 2022 survey. The differential decline in vaccine confidence in Asian participants compared to the pre-pandemic cohort might be interpreted in the light of the increasing amount of evidence indicating high levels of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy amongst individuals from Asian backgrounds [37], [38].

In the 2022 survey, a clear positive correlation was observed between the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses received by participants and their Vaccine Confidence Score. Median VCS was 15 for participants who did not receive any COVID-19 vaccine doses, 16 for those who only received one dose, 19 for those who received two doses, and 21 for those who received three doses. While it might be unsurprising that individuals with high vaccine confidence are more likely to have higher vaccine uptake, this finding reinforces the validity of the VCS as a powerful quantitative predictor of survey participants’ intentions to accept vaccinations.

5. Conclusions

This study provides evidence that vaccine confidence was significantly lower in the cohort surveyed in 2022 compared to the pre-pandemic cohort. While the reduction in confidence was observed across all demographic groups investigated, novel trends emerged in the post-pandemic cohort: the disappearance of the pre-pandemic trend whereby middle-aged respondents were significantly less confident than other age groups, and a statistically significant association between Asian ethnic backgrounds and low vaccine confidence.

The generalisability of the outcomes of this study is limited by the sampling strategy for two main reasons. The first is that different participants were recruited in the 2019 and 2022 surveys, meaning that this study does not provide a longitudinal view of the opinions of the same cohort before and after the onset of the pandemic. This was caused by the fact that, at the time the first survey was run, the investigators were unaware of the impending pandemic, and the study was therefore not designed to have a follow-up. The second limitation is the use of a non-probability sampling strategy, meaning that the makeup of the two cohorts was not necessarily identical or representative of the wider population. It should however be noted that the same recruitment and distribution modalities were used for the two surveys, and the cohort demographics as well as vaccine confidence trends are widely comparable between the two. Moreover, the statistical analysis strategy used in the study was to run internal comparisons between sub-groups within each cohort, meaning that the study effectively provides snapshots of two comparable population samples before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Regardless, further investigations are required to confirm to what extent the reduction in vaccine confidence observed between the two cohorts surveyed in this study is representative of different populations/countries. It may be beneficial for future studies to evaluate whether any changes in vaccine confidence in different populations are associated with how effectively the pandemic was handled by their respective government and with how severely COVID-19 impacted different countries.

While this is certainly not the only study to investigate vaccine hesitancy trends in relation to COVID-19, most previous studies focused on survey data collected after the WHO declared the pandemic status in March 2020. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to evaluate post-pandemic changes in vaccine confidence by analysing answers to the same set of questions in a pre- and post-pandemic cohort.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Megan Driscoll, Tia-mai Hurst, Tutu Coker, Alice Grantham, Amrit Bunet, Connor Chaffe, Aasimah Hanif, Varmetha Nitharsan and Hakeem Eyide for their help with the preparation and distribution of the surveys.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.10.061.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Vaccines and immunization; 2022.

- 2.Plotkin SL, Plotkin SA. A short history of vaccination. Vaccines 2004;5:1–16.

- 3.Bok K, Sitar S, Graham BS, Mascola JR. Accelerated COVID-19 vaccine development: milestones, lessons, and prospects. 8 ed. United States: Elsevier Science B.V., Amsterdam; 2021. p. 1636–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Falcaro M., Castañon A., Ndlela B., Checchi M., Soldan K., Lopez-Bernal J., et al. The effects of the national HPV vaccination programme in England, UK, on cervical cancer and grade 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia incidence: a register-based observational study. Lancet. 2021;398:2084–2092. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02178-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wakefield A.J., Murch S.H., Anthony A., Linnell J., Casson D.M., Malik M., et al. Elsevier; 1998. RETRACTED: Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hausman BL. Anti/Vax: reframing the vaccination controversy: Ilr Press; 2019.

- 7.Siani A. Vaccine hesitancy and refusal: history, causes, mitigation strategies. In: Rezaei N, editor. Integrated Science of Global Epidemics: Springer; 2022. ISBN: 978-3-031-17777-4, Series E-ISSN: 2662-947X.

- 8.Sreevatsava M., Burman A.L., Wahdan A., Safdar R.M., O'Leary A., Amjad R., et al. Routine immunization coverage in Pakistan: a survey of children under 1 year of age in community-based vaccination areas. Vaccine. 2020;38:4399–4404. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Ten threats to global health in 2019; 2019.

- 10.Siani A. Measles outbreaks in Italy: A paradigm of the re-emergence of vaccine-preventable diseases in developed countries. Prev Med. 2019;121:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacDonald N.E. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33:4161–4164. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Report of the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy; 2014.

- 13.Gerretsen P., Kim J., Caravaggio F., Quilty L., Sanches M., Wells S., et al. Individual determinants of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0258462. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Our World In Data. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations; 2022.

- 15.Ball P. The lightning-fast quest for COVID vaccines - and what it means for other diseases. Nature. 2021;589:16–18. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-03626-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Troiano G., Nardi A. Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19. Public Health. 2021;194:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nazlı Ş.B., Yığman F., Sevindik M., Deniz Ö.D. Psychological factors affecting COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Ir J Med Sci. 2022;191:71–80. doi: 10.1007/s11845-021-02640-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah A., Marks P.W., Hahn S.M. Unwavering Regulatory Safeguards for COVID-19 Vaccines. JAMA. 2020;324:931–932. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.15725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wouters O.J., Shadlen K.C., Salcher-Konrad M., Pollard A.J., Larson H.J., Teerawattananon Y., et al. Challenges in ensuring global access to COVID-19 vaccines: production, affordability, allocation, and deployment. Lancet. 2021;397:1023–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00306-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shapiro GK, Amsel R, Knauper B, Perez S, Rosberger Z, Tatar O, et al. The vaccine hesitancy scale: Psychometric properties and validation. Vaccine 2018;36:660-7-7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Siani A., Driscoll M., Hurst T.-M., Coker T., Grantham A.G., Bunet A. Investigating the determinants of vaccine hesitancy within undergraduate students' social sphere. J Public Health. 2021:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10389-021-01538-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fridman A., Gershon R., Gneezy A. COVID-19 and vaccine hesitancy: A longitudinal study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Temsah M.-H., Aljamaan F., Alenezi S., Alhasan K., Alrabiaah A., Assiri R., et al. SARS-COV-2 omicron variant: exploring healthcare workers' awareness and perception of vaccine effectiveness: a national survey during the first week of WHO variant alert. Front Public Health. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.878159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fadi A., Mohamad-Hani T., Khalid A., Shuliweeh A., Ali A., Abdulkarim A., et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants and the global pandemic challenged by vaccine uptake during the emergence of the Delta variant: A national survey seeking vaccine hesitancy causes. J Infect Public Health. 2022;15:773–780. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2022.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spetz M., Lundberg L., Nwaru C., Li H., Santosa A., Leach S., et al. The social patterning of Covid-19 vaccine uptake in older adults: A register-based cross-sectional study in Sweden. Lancet Reg Health Europe. 2022;15 doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arvanitis M., Opsasnick L., O'Conor R., Curtis L.M., Vuyyuru C., Yoshino Benavente J., et al. Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine trust and hesitancy among adults with chronic conditions. Prevent Med Rep. 2021;24 doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zintel S., Flock C., Arbogast A.L., Forster A., von Wagner C., Sieverding M. Gender differences in the intention to get vaccinated against COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Zeitschrift fur Gesundheitswissenschaften = J Public Health. 2022:1–25. doi: 10.1007/s10389-021-01677-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barry M., Temsah M.-H., Aljamaan F., Saddik B., Al-Eyadhy A., Alenezi S., et al. 40 ed: Elsevier Science B.V.; Amsterdam: 2021. COVID-19 vaccine uptake among healthcare workers in the fourth country to authorize BNT162b2 during the first month of rollout; pp. 5762–5768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Temsah M-H, Alhuzaimi AN, Aljamaan F, Bahkali F, Al-Eyadhy A, Alrabiaah A, et al. Parental attitudes and hesitancy about COVID-19 versus routine childhood vaccinations: a national survey. Front Public Health 2021:1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.McNaghten AD, Brewer NT, Mei-Chuan H, Peng-Jun L, Daskalakis D, Abad N, et al. COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage and Vaccine Confidence by Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity -- United States, August 29-October 30, 2021. MMWR: Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 2022;71:171–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Morales D.X., Beltran T.F., Morales S.A. Gender, socioeconomic status, and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the US: An intersectionality approach. Sociol Health Illn. 2022 doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.13474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kibongani Volet A., Scavone C., Catalán-Matamoros D., Capuano A. Vaccine Hesitancy Among Religious Groups: Reasons Underlying This Phenomenon and Communication Strategies to Rebuild Trust. Front Public Health. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.824560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dube E, Gagnon D, Nickels E, Jeram S, Schuster M. Mapping vaccine hesitancy-Country-specific characteristics of a global phenomenon. Great Britain: Elsevier Science B.V., Amsterdam.; 2014. p. 6649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Lee C.H.J., Sibley C.G. Attitudes toward vaccinations are becoming more polarized in New Zealand: Findings from a longitudinal survey. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;23 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel P.R., Berenson A.B. Sources of HPV vaccine hesitancy in parents. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2013;9:2649–2653. doi: 10.4161/hv.26224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siani A., Carter I., Moulton F. Political views and science literacy as indicators of vaccine confidence and COVID-19 concern. J Prevent Med Hygiene. 2022;63 doi: 10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2022.63.2.2320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Woolf K., McManus I.C., Martin C.A., Nellums L.B., Guyatt A.L., Melbourne C., et al. Ethnic differences in SARS-CoV-2 vaccine hesitancy in United Kingdom healthcare workers: Results from the UK-REACH prospective nationwide cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Europe. 2021;9 doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Razai M.S., Osama T., McKechnie D.G.J., Majeed A. Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy among ethnic minority groups. BMJ (Clinical Research ed) 2021;372 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.