Abstract

The existence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) subtypes has many important implications for the global evolution of HIV and for the evaluation of pathogenicity, transmissibility, and candidate HIV vaccines. The aim of this study was to establish a rapid method for determination of HIV-1 subtypes useful for a routine diagnostic laboratory and to investigate the distribution of HIV-1 subtypes in Austrian patients. Samples were tested by a subtyping method based on a 1.3-kb sequence of the polymerase gene generated by a commercially available drug resistance assay. The generated sequence was subtyped by means of an HIV sequence database. Results of 74 routine samples revealed subtype B (71.6%) as the predominant subtype, followed by subtype A (13.5%) and subtype C (6.8%). Subtypes E, F, G, and AE (CM240) were also detected. This subtyping method was found to be very easy to handle, rapid, and inexpensive and has proved suitable for high-throughput routine diagnostic laboratories. The specific polymerase gene sequence, however, must be existent.

Determination of the genetic subtypes of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) has been shown to be useful for understanding the origin and global spread of the virus. Subtyping may also be helpful for evaluation of pathogenicity, transmissibility, and candidate HIV vaccines.

The most informative method for determining the HIV-1 subtype is sequencing, either of the full-length genome or of partial gene regions such as the envelope, the group-specific antigen, or the polymerase gene (3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 20). Other direct HIV-1 subtyping methods include a probe hybridization assay, restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis, subtype-specific PCR, combinatorial melting assay, and the heteroduplex mobility assay (7, 13, 17, 19, 22). Furthermore, indirect HIV-1 subtyping by serotyping has been reported previously (14). A sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, which can be done on an automated instrument, has been evaluated but never brought on the market (18). All of those techniques lack standardization and automation. They are costly, laborious, and time-consuming. Therefore, they are not useful for a high-throughput routine diagnostic laboratory.

In contrast, the use of HIV-1 resistance testing in clinical practice is expanding rapidly. It has recently been recommended that antiretroviral drug resistance testing should be incorporated into patient management (9). Resistance testing is recommended to help guide the choice of new antiviral regimens after treatment failure and for guiding therapy for pregnant women. Furthermore, it should be considered in treatment-naïve patients with established infection and prior to initiating therapy in patients with acute HIV infection. Resistance testing can be done by genotyping or phenotyping. For genotyping, a standardized assay, the TruGene HIV-1 genotyping assay (Visible Genetics, Toronto, Ontario), is commercially available and currently under evaluation by the Food and Drug Administration (5). Because this assay is largely automated, it appears suitable for routine diagnostic laboratories.

The aim of this study was to establish a rapid method for determination of HIV-1 subtypes based on a 1.3-kb sequence of the polymerase gene generated with a TruGene HIV-1 Genotyping Kit. The generated sequence was subtyped by means of an HIV sequence database. Samples of Austrian patients with established HIV-1 infection were studied, and the subtyping results were analyzed with regard to risk group and geographic origin.

Blood specimens of 78 consecutive patients with established HIV-1 infection were included in this study. All specimens had been sent to a routine diagnostic laboratory in order to determine the plasma HIV-1 viral load and to test for antiretroviral drug resistance. Blood had been collected in 3.0-ml Vacutainer EDTA tubes (BD Vacutainer Systems, Franklin Lakes, N.J.). HIV-1 RNA was isolated by the ultrasensitive specimen preparation procedure of the Cobas Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor Test, version 1.5 (Roche Diagnostic Systems, Pleasanton, Calif.), according to the manufacturer's package insert instructions. After resuspension of the extracted HIV-1 RNA in 100 μl of HIV-1 diluent, 50 μl was used for the subsequent steps of the Cobas Amplicor HIV-1 Monitor Test. The remaining 50 μl was stored at −70°C.

The frozen HIV-1 RNA extract was thawed for HIV-1 resistance testing by sequencing of reverse transcriptase and protease genes with the TruGene HIV-1 Genotyping Kit according to the manufacturer's package insert instructions. Briefly, a 1.3-kb sequence of the polymerase gene of HIV-1 was reverse transcribed and amplified by PCR in a single tube. Sequencing reactions of protease and reverse transcriptase genes were generated from the amplification products by CLIP (Visible Genetics) sequencing. This technique allows both directions of the amplification products to be sequenced simultaneously in the same tube using two different dye-labeled primers for each of the four sequencing reactions. Electrophoresis and analysis of data were done with the automated OpenGene DNA sequencing system (Visible Genetics), which allows determination of the presence of all mutations, including drug resistance mutations. For electrophoresis, the automated Long-Read Tower was used. Data were acquired with the GeneLibrarian module of GeneObjects software by combination of the forward and reverse sequences and comparison to a standard HIV-1 sequence.

Determination of HIV-1 subtypes was done by means of the HIV Sequence Database (hyperlink http://hiv-web.lanl.gov/) provided by Bette Korber and her colleagues at the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL). The entire 1.3-kb sequence of the polymerase gene of HIV-1 was downloaded in a special format (FASTA format, which is outlined at the above-named website) and entered in the BLAST search site, which is one of the subpages of the homepage mentioned above. All BLAST outputs begin with a listing of the best matches to the query sequence, followed by an alignment of the query sequence to its matches. HIV-1 subtypes are determined as the best matches obtained by the BLAST search.

Contamination was prevented by careful lab work, including the use of separate rooms for sample preparation, amplification, sequencing reactions, and electrophoresis, and periodical screening for contamination as recommended by the LANL, including special analyses performed when protease and reverse transcriptase genes were present.

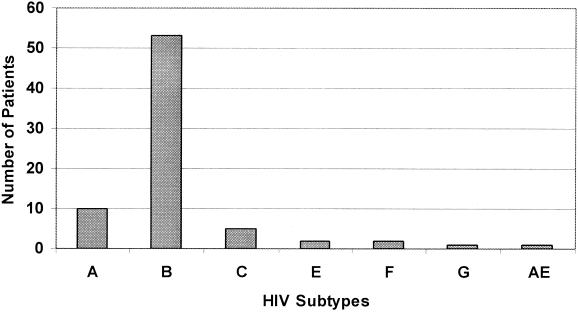

In 74 of 78 routine samples (94.9%), an unambiguous subtyping result was found. Four untypeable samples gave sequences of insufficient quality to allow a subtype to be assigned by the employed method. Results obtained by 74 routine samples are shown in Fig. 1. The most common subtype was subtype B (71.6%), followed by subtype A (13.5%) and subtype C (6.8%). Two patients were diagnosed with subtypes E and F, one patient was diagnosed with subtype G, and one patient was diagnosed with the circulating recombinant form AE (CM240). Subtype D was not diagnosed in any of the studied patients.

FIG. 1.

Prevalence of HIV-1 subtypes in Austrian HIV-1 patients.

Subtype B was most commonly found among Austrian patients. With regard to personal risk, heterosexual relations, intravenous drug abuse, hemophilia, and homosexuality were found most frequently. Thirteen of 16 patients infected with subtypes A, C, or G originated from African countries. The remaining three were Austrians who had been infected by African partners. Of the two patients with subtype E, one was an Austrian male who had been in Thailand for sex tourism. The other patient with subtype E was an Austrian female who had been infected by an unknown partner. Of the two patients with subtype F, one was an abandoned Romanian child with a malignancy. This 11-year-old girl had been taken to the Department of Pediatrics, Karl-Franzens-University Graz, to receive special anticancer therapy. The girl had received blood transfusions in Romania earlier. The other patient with subtype F originated from Africa. No history was available for the patient with the circulating recombinant form AE (CM240).

The HIV-1 subtyping method employed in this study proved to be suitable for a routine diagnostic laboratory. Following generation of the specific polymerase gene sequence with a commercially available kit, HIV-1 subtyping required a standard personal computer with internet connection and could be carried out in less than 15 min.

There is a need for methods that can be used to assign a subtype in a rapid, reproducible, and inexpensive way. The definitive method of characterizing the genome of an HIV-1 isolate is to sequence it in its entirety (4, 8, 12). Sequencing complete genomes, however, is inappropriate for routine diagnostic laboratories with high throughput, and less complicated methods must be employed. It has been shown that sequencing a single genomic region such as the envelope, the group-specific antigen, or the polymerase gene usually allows the assignment of a subtype (3, 6, 20). It will, however, not necessarily reveal any mosaic structure.

Antiretroviral drug resistance testing has recently been recommended for patient management (9). Resistance testing is currently costly, which also applies to the commercially available drug resistance assay employed in this study. This assay is, however, relatively easy to handle and can be introduced in routine diagnostic laboratories. Only a part of the HIV-1 polymerase gene is a prerequisite of the described HIV-1 subtyping method, which does not involve additional material costs and can be performed by a trained medical technologist in less than 15 min. Compliance with the quality control measures displayed on the corresponding LANL web pages (in particular, phylogenetic analysis of the similarity of the sequences) is strongly recommended.

Subtyping results revealed that, similar to what obtains in other European countries, subtype B is the predominant subtype in Austria (central Europe). However, a growing range of non-B subtypes has been reported, especially in North America and several European countries, mainly for persons who have traveled to other continents or immigrated from them (1, 2, 10, 11). In this study, a considerable number of patients with subtype A or C were found. The majority of these patients, including the one infected with subtype G, originated from Africa, and the remaining patients had obviously acquired the virus from African partners. Africa is considered to be a source area for subtype A, but a considerable prevalence of non-A subtypes, including subtypes C, D, F, G, H, J, K, and AE (CRF01), has recently been found in central Africa (23). Sex tourism seems to be the main source of infection with subtype E in Europe. It has been reported that subtype E, which circulates predominantly in Thailand, exhibits a specific tropism for Langerhans cells, which have been suggested to be associated with a more efficient heterosexual transmission rate (21). Subtype F seems to be relatively frequent in Romania. It has been reported that nearly 80% of AIDS patients in Romania are children who for the most part have been abandoned or are orphans (15). There is evidence that most of them were infected by blood transfusions (16).

In conclusion, results of this study reflect the present situation regarding the prevalence of HIV-1 subtypes in central Europe, with subtype B still being the predominant subtype but several HIV-1 subtypes other than B having emerged in the region. The method for determination of HIV-1 subtypes proved to be useful for a high-throughput routine diagnostic laboratory. It was found to be easy to handle, rapid, and inexpensive. It is, however, based on the existence of the specific sequence of the polymerase gene generated by a commercially available kit.

Acknowledgments

We thank Thomas Hawranek, Judith Hutterer, Manfred Kanatschnig, Andreas Kapper, Max Kronawetter, and Horst Schalk for fruitful collaboration.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adwan G, Papa A, Kouidou S, Alexiou S, Ialissiovas N, Itoutsos I, Kiosses V, Antoniadis A. Genetic heterogeneity of HIV-1 in Greece. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:353–357. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)00332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alaeus A, Leitner T, Lidman K, Albert J. Most HIV-1 genetic subtypes have entered Sweden. AIDS. 1997;11:199–202. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199702000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barlow K L, Tosswill J H, Clewley J P. Analysis and genotyping of PCR products of the Amplicor HIV-1 kit. J Virol Methods. 1995;52:65–74. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(94)00139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carr J K, Salminen M O, Albert J, Sanders-Buell E, Gotte D, Birx D L, McCutchan F E. Full genome sequences of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtypes G and A/G intersubtype recombinants. Virology. 1998;247:22–31. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clevenbergh P, Durant J, Halfon P, del Giudice P, Mondain V, Montagne N, Schapiro J M, Boucher C A, Dellamonica P. Persisting long-term benefit of genotype-guided treatment for HIV-infected patients failing HAART. The Viradapt Study: week 48 follow-up. Antivir Ther. 2000;5:65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cornelissen M, Kampinga G, Zorgdrager F, Goudsmit J. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtypes defined by env show high frequency of recombinant gag genes: the UNAIDS Network for HIV Isolation and Characterization. J Virol. 1996;70:8209–8212. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8209-8212.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delwart E L, Shpaer E G, Louwagie J, McCutchan F E, Grez M, Rübsamen-Waigmann H, Mullins J I. Genetic relationship determined by a DNA heteroduplex mobility assay: analysis of HIV-1 env genes. Science. 1993;262:1257–1261. doi: 10.1126/science.8235655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao F, Robertson D L, Carruthers C D, Morrison S G, Jian B, Chen Y, Barre-Sinoussi F, Girard M, Srinivasan A, Abimiku A G, Shaw G M, Sharp P M, Hahn B H. A comprehensive panel of near-full-length clones and reference sequences for non-subtype B isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1998;72:5680–5698. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.7.5680-5698.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirsch M S, Brun-Vezinet F, D'Aquila R T, Hammer S M, Johnson V A, Kuritzkes D R, Loveday C, Mellors J W, Clotet B, Conway B, Demeter L M, Vella S, Jacobsen D M, Richman D D. Antiviral drug resistance testing in adult HIV-1 infection. Recommendations of an international AIDS society—USA panel. JAMA. 2000;283:2417–2426. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.18.2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irwin K L, Pau C P, Lupo D, Pienazek D, Luo C C, Olivo N, Rayfield M, Hu D J, Weber J T, Respess R A, Janssen R, Minor P, Ernst J. Presence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 subtype A infection in New York community with high HIV prevalence: a sentinel site for monitoring HIV genetic diversity in North America. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1629–1633. doi: 10.1086/517343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lasky M, Perret J L, Peeters M, Bibollet-Ruche F, Liegeois F, Patrel D, Molinier S, Gras C, Delaporte E. Presence of multiple non-B subtypes and divergent subtype B strains of HIV-1 in individuals infected after overseas deployment. AIDS. 1997;11:43–51. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199701000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lole K S, Bollinger R C, Paranjape R S, Gadkari D, Kulkarni S S, Novak N G, Ingersoll R, Sheppard H W, Ray S C. Full-length human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomes from subtype C-infected seroconverters in India, with evidence of intersubtype recombination. J Virol. 1999;73:152–160. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.152-160.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo C C, Downing R G, dela Torre N, Baggs J, Hu D J, Respess R A, Candal D, Carr L, George J R, Dondero T J, Biryahwaho B, Rayfield M A. The development and evaluation of a probe hybridization method for subtyping HIV type 1 infection in Uganda. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1998;14:691–694. doi: 10.1089/aid.1998.14.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy G, Belda F J, Pau C P, Clewley J P, Parry J V. Discrimination of subtype B and non-subtype B strains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by serotyping: correlation with genotyping. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1356–1360. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.5.1356-1360.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nedelcu I. AIDS in Romania. Am J Med Sci. 1992;304:188–191. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199209000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Op de Coul E, van den Burg R, Asjo B, Goudsmit J, Cupsa A, Pascu R, Usein C, Cornelissen M. Genetic evidence of multiple transmissions of HIV type 1 subtype F within Romania from adult blood donors to children. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2000;16:327–336. doi: 10.1089/088922200309205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peeters M, Liegeois F, Bibollet-Ruche F, Patrel D, Vidal N, Esu-Williams E, Mboup S, Mpoudi Ngole E, Koumare B, Nzila M, Perret J L, Delaporte E. Subtype-specific polymerase chain reaction for the identification of HIV-1 genetic subtypes circulating in Africa. AIDS. 1998;12:671–673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pierer K, Kessler H H, Kasper P, Kronawetter M, Santner B, Marth E. Prevalence of HIV-1 serotypes in HIV-1 patients of southern Austria. Biotest Bull. 1997;5:261–263. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robbins K E, Kostrikis L G, Brown T M, Anzala O, Shin S, Plummer F A, Kalish M L. Genetic analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains in Kenya: a comparison using phylogenetic analysis and a combinatorial melting assay. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1999;15:329–335. doi: 10.1089/088922299311295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soto-Ramirez L E, Tripathy S, Renjifo B, Essex M. HIV-1 pol sequences from India fit distinct subtype pattern. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovir. 1996;13:299–307. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199612010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soto-Ramirez L E, Renjifo B, McLane M F, Marlink R, O'Hara C, Sutthen T R, Wasi C, Vithayasai P, Vithayasai V, Apichartpiyakul C, Auewarakul P, Pena Cruz V, Chui D S, Osathanondh R, Mayer K, Lee T H, Essex M. Langerhans' cell tropism associated with heterosexual transmission of HIV. Science. 1996;271:1291–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5253.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Harmelen J, van der Ryst E, Wood R, Lyons S F, Williamson C. Restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis for rapid gag subtype determination of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in South Africa. J Virol Methods. 1999;78:51–59. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(98)00163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vidal N, Peeters M, Mulanga-Kabeya C, Nzilambi N, Robertson D, Ilunga W, Sema H, Tshimanga K, Bongo B, Delaporte E. Unprecedented degree of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) group M genetic diversity in the Democratic Republic of Congo suggests that the HIV-1 pandemic originated in central Africa. J Virol. 2000;74:10498–10507. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.22.10498-10507.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]