Summary

The rapid increase in inpatients during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic acutely increased the workload of physicians and nurses caring for severely ill patients. Moreover, family visits were restricted for infection control purposes, and family members were unable to be briefed regarding a patient's condition because they tested positive or they had been in close contact with an infectious patient, thus increasing the burden on the patient's family and the medical staff. Therefore, our psychiatric liaison team intervened by attending briefing sessions for family members and online patient visits while also conducting sessions to provide information about mental health and relaxation sessions for the hospital's nurses to reduce their burden as much as possible. These efforts provided mental support for the patients' families while also reducing the challenges of and the burden on medical staff. If the number of severely ill patients increases rapidly and the burden on patients' families and medical staff increases, then we hope that these efforts will help to provide better psychological support to both families and staff.

Keywords: COVID-19, team medicine, psychiatric liaison team, family support, bereaved family care, online patient visits

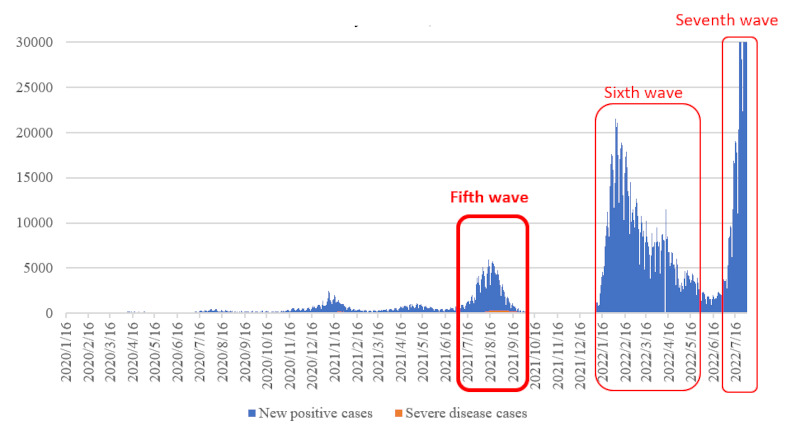

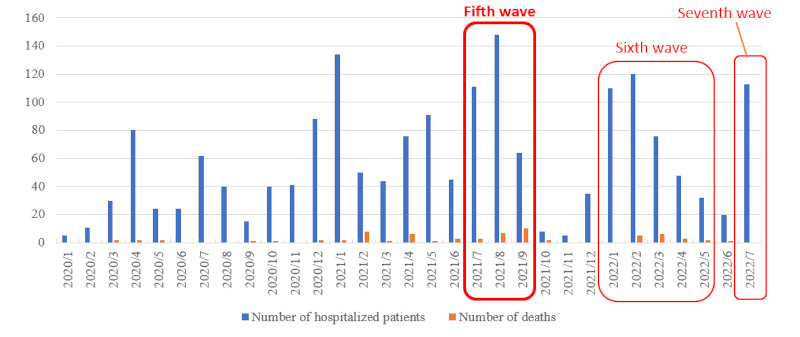

More than 2 years has passed since the extensive spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), and several waves of the infection have come and gone. In particular, the fifth wave in Japan saw a rapid increase in the number of patients with COVID-19 nationwide (Figure 1) (1), which also led to an increase in patients with severe COVID-19 (hereinafter referred to as severely ill patients) hospitalized at the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (NCGM) as well as mortality (Figure 2). This led to a mounting physiological and psychological burden, causing anxiety for the staff treating and caring for those patients. Numerous studies in Japan and abroad have reported the mental health problems that healthcare professionals have faced during the COVID-19 pandemic (2-5). Moreover, the NCGM has been forced to restrict visits to inpatients since March 2020 for infection control purposes, further increasing the burden on the patients themselves and the medical staff that care for them.

Figure 1.

New positive cases/cases of severe disease in Tokyo, Japan. Data from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare.

Figure 2.

Number of hospitalizations/deaths due to COVID-19 in this hospital from January 2020 to July 2022.

This report discusses the Psychiatric Liaison Team's efforts in a ward for severely ill patients in which patients with severe COVID-19 were being treated and cared for during the fifth wave of the pandemic.

The Psychiatric Liaison Team is a team whose multidisciplinary staff, including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and clinical psychologist, collaborate with physicians and nurses in charge of each department to bridge the gap between psychiatric care and physical care and to provide more comprehensive medical care to inpatients. The activities of the Team are expected to increase the effectiveness of medical care (6). The NCGM's Psychiatric Liaison Team (hereinafter referred to as "the Team") consists of individuals from multiple professions, namely psychiatrists, a certified nurse specialist in psychiatric mental health nursing, and a psychotherapist. Capitalizing on their expertise, they provide team medical care to inpatients and their families who find themselves in complicated social and psychological states.

Circumstances for severely ill patients and their families

The impact of the ban on visitation was greater than expected for severely ill patients and their families and the medical staff in the ward in question. Patients' families experienced various hardships and internal conflicts, such as not knowing the patient's status and being unable to touch the patient, much like the severely ill patients themselves. Nurses working on the ward had to spend many hours responding to phone calls from patients' families who were barred from visitation (at times, the families would express demands, requests, anxiety, and anger), which sometimes interfered with other work.

Doctors and nurses who treat and care for severely ill patients who require advanced medical care have also been under heavy stress. When briefing families about patients' conditions, doctors often have to convey the difficult details of the patient's condition, which would normally require careful family support. However, adequate family support was not provided due to the heavy workload of nurses in charge of the site.

Moreover, severely ill patients with cluster infections in the family had family members who had been instructed to stay at home or who were admitted to other hospitals, which prevented some families from visiting the NCGM. In such circumstances, even serious details about a patient's condition had to be explained over the telephone, which meant that hospital staff could not correctly ascertain the family's response after the briefing. In one case, the ward staff could not intervene even though the family was grieving profoundly and they had trouble accepting the situation. In August 2021, the ward's Head Nurse and a department doctor provided the Team with information about these situations.

What was expected of the Team

Soon after the briefing session by the ward's Head Nurse and a department doctor, the Team's psychiatric nursing specialist and psychotherapist solicited opinions about the Team's role. They confirmed that the following was needed from the Team: i) for a member of the liaison team to be in attendance to provide psychological support to the patients' families during a briefing session, which is expected to induce profound grief and shock in patients' families; ii) to follow-up with the patients' families about the patient's condition after the briefing session (to continue to meet with and provide psychological support to the patients' families); iii) to arrange online visits by families (from a location outside the hospital, such as at home) because some could not visit the hospital; and 4) to provide mental health support to the nursing team working in the ward for severely ill patients.

What the Team has done

The following support was provided based on the ward's needs: i) patient family support: the Team's psychiatric nursing specialist or psychotherapist oversaw the briefing sessions on the patient's condition and online visits by the patient's family. They provided support so that the family could readily communicate with doctors and nurses, ask questions, and understand the patient's current situation. Through interviews with the families, they evaluated and confirmed the physical condition and psychological state of the family and also provided self-care education (sleep hygiene guidance, ideas about what to eat, and relaxation breathing); ii) bereaved family care: for the family members of patients who died of COVID-19, the Team arranged a setting in which the Team could continue to interview the family if they so wished, and they informed the family members to that effect; iii) made arrangements for online visits: the Team consulted with the department in charge at the hospital based on the Team's experience with prior online visits to see if online visits could be made from the outside (outside the hospital, such as from the patient's home), but external online visits were not possible; and iv) mental health support for the ward-based nursing team: the psychiatric nurse of the Team and clinical psychologist in the staff consultation department of the NCGM conducted mental health briefing sessions and relaxation sessions for the nursing team on the ward.

Effects of the Team's involvement

There were nine cases in which a member of the Team oversaw briefing sessions on the patient's condition and online visits by the patient's family as a form of family support. Patients' families had many positive things to say about the briefing sessions and online visits, such as "I was relieved to see my loved one's actual state on the iPad screen. Being able to convey my feelings to my loved one was nice" and "I am very thankful to the doctors and nurses who are doing their best." The bereaved families of patients who died of COVID-19 were informed that the Team can continue providing bereavement care, but no family members have requested it so far.

Changes in the ward staff were also noted; the doctors of the ward said that "the Team helped to reduce the burden of the briefing sessions on the patient's condition and providing family support" and "this provides us with a new system to deal with a rapid increase in COVID-19 infections and hospital admissions going forward." The Team's involvement affected the patients' families and it provided support to on-site staff.

Next steps for the Team

The Team has not been asked to care for a bereaved family thus far, but a study has reported that the need for bereaved family care is increasing due to the COVID-19 pandemic (7), and the creation of a system for bereaved family care will need to be considered in the future (providing information to bereaved families and greater access to bereaved family care).

Online visits both connect patients with their families and also connect patients' families with healthcare professionals. Patients' families need to be given safe places and ways to watch over their ill family member so that they are better prepared to accept the patient's death, and bereaved families need to receive specialized support even after the patient's death (8). These observations suggest that online visits that allow family members to safely see the patient should be made more accessible. At the NCGM, however, this cannot be implemented yet, despite family requests for online visits from the outside (access outside the hospital, such as at the family's home). The issues raised in conjunction with this lack of implementation include the inability of hospital staff to help the patient and family members understand how to operate the devices and security problems for the NCGM. These issues need to be addressed first.

The burden on the families of severely ill patients and the medical staff that care for these patients was greater than expected, and the burden on families and medical staff is expected to increase as the number of severely ill patients increases and responses become prolonged as the infection continues to spread. If the number of infected or severely ill patients increases again, the Team would like to capitalized on its previous efforts and implement a wide range of approaches to help support patients, patients' families, and medical staff as well.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to particularly thank all of the ward doctors, head nurses, and nursing teams that cooperated with the authors' team efforts. The authors would also like to thank Mr. Otomo from the NCGM's Department of Psychiatry for assistance writing and editing this manuscript.

Funding:

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare. Visualizing the data: Information on COVID-19 infections. https://covid19.mhlw.go.jp/ (accessed August 25, 2022). (in Japanese) .

- 2. Watanabe Y, Someya T. Feature Article - Suicide prevention measures during the COVID-19 pandemic and the mental health of healthcare workers. Japanese Journal of Public Health. 2021; 85:156-159. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hamouche S. COVID-19 and employees' mental health: Stressors, moderators and agenda for organizational actions. Emerald Open Research. 2020; 2:15. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Giorgi G, Lecca LI, Alessio F, Finstad GL, Bondanini G, Lulli LG, Arcangeli G, Mucci N. COVID-19-related mental health effects in the workplace: A narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17:7857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sasaki N, Kawakami N. Mental health among workers in the COVID-19 pandemic: A review. Occupational Health Review. 2021; 34:17-50. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yoshimura Y, Kiriyama K, Fujiwara S. Current status and problems of the psychiatric liaison team. Japanese Journal of General Hospital Psychiatry. 2013; 25:2-8. (in Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- 7. Matsuda Y, Takebayashi Y, Nakajima S, Ito M. Managing grief of bereaved families during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Front Psychiatry. 2021; 12:637237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Firouzkouhi M, Alimohammadi N, Abdollahimohammad A, Bagheri G, Farzi J. Bereaved families views on the death of loved ones due to COVID 19: An integrative review. Omega (Westport). 2021:302228211038206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]