Abstract

Rationale:

The metabolic acidoses are generally separated into 2 categories on the basis of an anion gap calculation: high-anion-gap and normal anion-gap metabolic acidosis. When a high-anion-gap metabolic acidosis (HAGMA) is not clearly explained by common etiologies and routine confirmatory testing, specialized testing can definitively establish rare diagnoses such as 5-oxoproline, d-lactate accumulation, or diethylene glycol toxicity.

Presenting Concerns of the Patient:

A 56-year-old woman had a prolonged hospital admission following perforated diverticulitis requiring sigmoid resection. Her hospitalization was complicated by feculent peritonitis and surgical wound dehiscence needing prolonged broad-spectrum antibiotics and wound debridements. She developed acute kidney injury and HAGMA in the hospital.

Diagnoses:

Chart review showed that she received a large cumulative dose of acetaminophen during her hospital stay. Laboratory studies showed markedly increased serum 5-oxoproline causing HAGMA.

Interventions (Including Prevention and Lifestyle):

Patient was admitted to the intensive care unit and treated with N-acetylcysteine and renal replacement therapy.

Outcomes:

After admission to the intensive care unit, the patient continued to require vasopressor and ventilatory support for septic shock and a ventilator-associated pneumonia. After an initial recovery and resolution of her HAGMA, she subsequently suffered recurrent aspirations which were fatal.

Teaching points:

1. The acronym GOLD MARK is useful when assessing patients with HAGMA and most causes of HAGMA can be established with routine testing.

2. When the etiology of HAGMA remains unclear, additional testing can be required to diagnose rare causes of HAGMA.

3. Rare causes of HAGMA are diethylene glycol, 5-oxoproline, and d-lactate accumulation.

4. Acidosis secondary to 5-oxoproline accumulation can occur even with “therapeutic” doses of acetaminophen in patients receiving it regularly for a prolonged period and who have depleted glutathione stores.

5. Risk factors for glutathione depletion include malnutrition, older age, sepsis, pregnancy, multiple chronic illnesses, and chronic kidney disease.

Keywords: high-anion-gap metabolic acidosis, 5-oxoproline, acetaminophen, d-lactate acidosis, glutathione

Abrégé

Justification:

Les acidoses métaboliques sont généralement classées en deux catégories sur la base d’un calcul de trou anionique : les acidoses métaboliques à trou anionique élevé (HAGMA – High anion gap metabolic acidosis) et les acidoses métaboliques à trou anionique normal. Lorsque l’acidose métabolique à trou anionique élevé n’est pas clairement expliquée par des étiologies courantes et des tests de confirmation de routine, des tests spécialisés peuvent établir de façon définitive des diagnostics rares tels que l’accumulation de 5-oxoproline, l’accumulation de D-lactate ou une toxicité du diéthylène glycol.

Présentation du cas:

Une femme de 56 ans hospitalisée de façon prolongée à la suite d’une diverticulite perforée nécessitant une résection du sigmoïde. L’hospitalisation a été compliquée par une péritonite purulente et une déhiscence de la plaie chirurgicale ayant nécessité un débridement de la plaie et une antibiothérapie à large spectre prolongée. La patiente a développé une insuffisance rénale aiguë (IRA) et une HAGMA durant son séjour à l’hôpital.

Diagnostic:

L’examen du dossier a montré que la patiente avait reçu une dose cumulative importante d’acétaminophène pendant son séjour à l’hôpital. Des analyses en laboratoire ont montré une augmentation marquée de la 5-oxoproline sérique ayant causé l’HAGMA.

Interventions (y compris prévention et mode de vie):

La patiente a été admise à l’unité des soins intensifs et traitée par N-acétylcystéine et thérapie de remplacement rénal (TRR).

Résultats:

Après son admission à l’USI, la patiente a continué d’avoir besoin de vasopresseur et d’assistance respiratoire en raison d’un choc septique et d’une pneumonie associée au ventilateur. Après un rétablissement initial et la résolution de son HAGMA, la patiente a ensuite dû subir des aspirations récurrentes qui lui ont été fatales.

Enseignements tirés:

1. L’acronyme GOLD MARK est utile lors de l’évaluation des patients atteints d’HAGMA; la plupart des causes d’HAGMA peuvent être établies avec des tests de routine.

2. Lorsque l’étiologie de l’HAGMA reste incertaine, des tests supplémentaires peuvent être nécessaires pour diagnostiquer les causes rares de l’HAGMA.

3. Les causes rares de HAGMA sont une accumulation de diéthylène glycol, de 5-oxoproline et de D-lactate.

4. L’acidose secondaire à une accumulation de 5-oxoproline peut se produire même avec des doses « thérapeutiques » d’acétaminophène chez les patients qui l’ont reçu régulièrement pendant une période prolongée et qui ont épuisé leurs réserves de glutathion.

5. Les facteurs de risque pour l’épuisement des réserves de glutathion incluent la malnutrition, l’âge plus avancé, la septicémie, la grossesse, les maladies chroniques multiples et l’insuffisance rénale chronique.

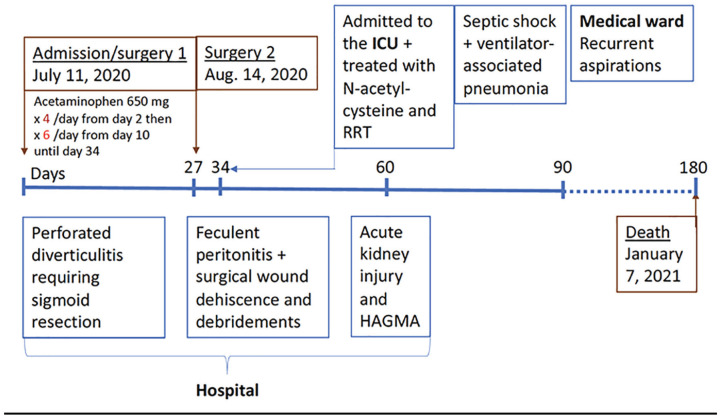

Timeline

Introduction

The metabolic acidoses are generally separated into 2 categories on the basis of an anion gap (AG) calculation (AG = Na+ − (Cl− + HCO3−)): high-anion-gap metabolic acidoses, and normal-anion-gap, or hyperchloremic, metabolic acidosis. Normal AG acidoses are most often due to gastrointestinal or renal bicarbonate loss.1 The differential diagnosis of high-anion-gap metabolic acidosis (HAGMA) is well known (Table 1),1 and, in most cases, the cause can be confirmed with routinely available testing. HAGMA due to 5-oxoproline or d-lactate accumulation, or diethylene glycol toxicity, is relatively rare and routine testing for these entities is not performed. Nonetheless, in the absence of a clear explanation for HAGMA after initial testing, focused history-taking and additional tests can establish a specific cause. This is particularly important as treatments for rarer causes of HAGMA can be lifesaving and differ according to the etiology. Here, we present a case of HAGMA, which developed during a prolonged hospitalization. The cause was ultimately confirmed to be 5-oxoproline accumulation. In addition to 5-oxoproline, d-lactate acidosis was a potential consideration, and we use this case to review the pathophysiology and management of these relatively rarer causes of HAGMA.

Table 1.

Differential Diagnosis of High-Anion-Gap Metabolic Acidosis Using the GOLD MARK Acronym, From Mehta et al.1

| • Glycols (Diethylene and Propylene) • 5-Oxoproline accumulation • l- and d-Lactate accumulation • Methanol • Aspirin • Renal failure • Ketoacidosis |

Presenting Concerns

A 56-year-old woman, who was previously known only for a history of schizophrenia, was admitted to the hospital 2 months prior to our assessment due to perforated diverticulitis which required sigmoid resection. Her hospitalization was complicated by an anastomotic leak, the need for a defunctioning ileostomy, feculent peritonitis, and surgical wound dehiscence requiring percutaneous drainage, laparotomy, prolonged broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment, and wound debridements over several weeks. She was ordered to receive a high-protein/caloric diet due to elevated ileostomy outputs; however, her intake remained poor. For pain management, she was given acetaminophen 650 mg 4 times per day following admission (total dose of 78 g), and over a 3-week period, her dose was increased to 650 mg every 4 hours (3.9 g/d).

Clinical Findings

On the day of our assessment, she was transferred to the intensive care unit for hypovolemic shock that was thought to be from high gastrointestinal losses and poor oral intake. She was found with new abdominal collections, acute kidney injury (AKI), and HAGMA (Table 2).

Table 2.

Electrolytes and Arterial Blood Gas Testing Relative to the Patient’s ICU Admission With a Severe High-Anion-Gap Metabolic Acidosis.

| Reference interval | Day 2 | Day 1 | ICU day 0 | Day 1 | Day 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na+, mmol/L | 136-144 | 136 | 141 | 143 | 144 | 140 |

| K+, mmol/L | 3.5-5.1 | 3.4 | 4.2 | 3.9 | 3.6 | 4.8 |

| Cl−, mmol/L | 98-107 | 102 | 110 | 110 | 110 | 101 |

| Total CO2, mmol/L | 19-30 | 10 | 6 | 5 | 9 | 25 |

| Anion gap, mmol/L | 8-16 | 22 | 26 | 28 | 25 | 14 |

| Creatinine, µmol/L | 49-84 | 136 | 183 | 181 | 178 | 67 (post-SLED) |

| Glucose, mmol/L | 4-11 | 5.0 | 6.3 | — | — | 7.2 |

| Urea, mmol/L | 2.4-6.4 | — | 12.4 | 13.2 | 12.6 | — |

| Albumin, g/L | 39-47 | 24 | 22 | 24 | — | — |

| Urine anion gap, mmol/L | n/a | — | — | 51 | — | — |

| Urine osmolarity, mOsm/kg | n/a | — | — | 308 | — | — |

| Serum osmolality, mOsm/kg | 280-295 | — | — | 319 | — | — |

| Arterial blood gas | ||||||

| pH | 7.38-7.46 | — | — | 6.92 | 7.17 | 7.42 |

| PaCO2, mm Hg | 32-45 | — | — | 18 | 30 | 47 |

| Bicarbonate, mmol/L | 22-27 | — | — | 6 | 11 | 29 |

| Hb sat. % | 95-98 | — | — | 95 | 97 | 95 |

| Lactate whole blood, mmol/L | 0.5-2.5 | — | — | 0.6 | 0.8 | — |

Note. SLED = sustained low-efficiency dialysis.

Diagnostic Focus and assessment

Her initial investigations revealed a negative alcohol screen (ethanol, methanol, isopropanol, ethylene glycol), normal liver function tests, lactate, negative for salicylates, and mildly elevated beta-hydroxybutyrate (0.56 mmol/L [reference interval <0.27 mmol/L]).

Although the patient’s AG elevation might have been partially explained by AKI and elevated beta-hydroxybutyrate, the AG elevation was disproportionately high. Serum osmolal gap was elevated (19 mOsm/kg), probably in the setting of AKI. Using the mnemonic GOLD MARK,1 an acronym for glycols (ethylene and propylene), oxoproline (5-oxoproline also called pyroglutamic acid), l-lactate, d-lactate, methanol, aspirin, renal failure, and ketoacidosis, we determined that there were 3 additional potential causes that needed to be ruled out with further history-taking and testing. First was d-lactic acidosis, typically seen in patients with short gut syndrome. Second, 5-oxoproline acidosis, associated with chronic acetaminophen ingestion, has been well-documented in the literature.2-4 Although possible, diethylene glycol toxicity was presumed to be much less likely given no history of toxic exposure or ingestion in the context of a prolonged hospitalization. Given her reduced kidney function, malnutrition, and chronic acetaminophen ingestion, we suspected 5-oxoproline accumulation. Her serum level of acetaminophen was <33 µmol/L.

Therapeutic Focus and Assessment

Acetaminophen was stopped and the patient was started on volume expansion with dextrose and bicarbonate drip. N-acetyl cysteine (60 mg/kg) was administered to empirically treat the associated glutathione and cysteine deficiency to limit any potential further conversion of γ-glutamyl phosphate to 5-oxoproline. Sustained low-efficiency dialysis (SLED) was also initiated for severe acidosis. Urine organic acid testing revealed a markedly increased excretion of 5-oxoproline, with smaller increases in the excretion of lactic and pyruvic acids. This confirmed the diagnosis of 5-oxoproline accumulation as the primary driver of the patient’s HAGMA. The HAGMA improved after providing N-acetylcysteine and 2 days of SLED treatments as well as treatment for intra-abdominal sepsis.

Follow-up and Outcomes

The patient continued to require vasopressor and ventilatory support for septic shock and a ventilator-associated pneumonia but subsequently she improved and was transferred back to the medical ward. Unfortunately, her subsequent course was complicated by recurrent aspirations and she ultimately passed away, likely due to respiratory failure following an aspiration event.

Discussion

In the rare cases, where a patient has a HAGMA that is not explained by obvious etiologies, additional history and testing can establish the cause and lead to specific (and potentially lifesaving) treatments: 5-oxoproline (N-acetylcysteine), d-lactate (source control and antibiotics), diethylene glycol (dialysis).

In our patient, after ruling out common causes of HAGMA, the 2 main differential diagnoses of HAGMA remaining were 5-oxoproline or d-lactate accumulation (Figure 1). Diethylene glycol poisoning most often occurs in the context of exposure to brake fluid (oral ingestion or, potentially, topical exposure) and has been related to pill contamination in children, but was less likely in a hospitalized patient.

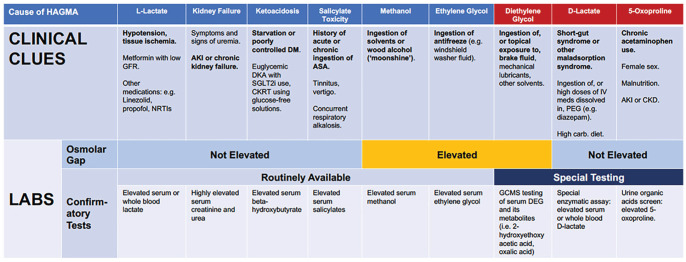

Figure 1.

Clinical clues and laboratory testing for causes of HAGMA.

Note. CKD = chronic kidney disease; HAGMA = high-anion-gap metabolic acidosis; GFR = glomerular filtration rate; NRTIs = nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; AKI = acute kidney injury; DM = diabetes mellitus; DKA = diabetic ketoacidosis; SGLT2i = sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors; CKRT = continuous kidney replacement therapy; ASA = acetylsalicylic acid; IV meds = intravenous medications; PEG = polyethylene glycol; carb = carbohydrate; GCMS = gas chromatography mass spectroscopy; DEG = diethylene glycol.

5-Oxoproline Accumulation

5-Oxoproline is a tripeptide that contains glutamic acid, cysteine, and glycine. It is an antioxidant involved in several important metabolic reactions including detoxification of many drugs. Accumulation of 5-oxoproline can occur via several mechanisms that cause decreased production of glutathione and the primary one being glutathione synthetase deficiency. Inherited deficiencies of glutathione synthetase are rare and commonly autosomal recessive. They manifest at an early age with mental retardation, ataxia, hemolytic anemia, and chronic metabolic acidosis.5 There might be a sex-based predisposition for 5-oxoproline acidosis, with women more likely than men to be diagnosed with the condition,3 due to sex-based differences in the activity of several isoenzymes in the gamma-glutamyl cycle.6 Another rare cause includes 5-oxoprolinase deficiency which typically presents as kidney stones (due to 5-oxoprolinuria) at a young age.3

The acquired form of glutathione synthetase deficiency is related to irreversible binding of one of the metabolites of acetaminophen, N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone-imine (NAPQI) to glutathione which is mostly stored in the liver. Acetaminophen toxicity develops when 80% of the intracellular content of glutathione is depleted. This provokes an increase in gamma-glutamyl cysteine synthetase activity and the resulting elevated gamma-glutamyl cysteine levels are partially converted to 5-oxoproline. This has been described in multiple cases in the literature (see Kalinoski7 for review). It is interesting to note that in the vast majority of cases reported in the literature, a common feature was chronic ingestion of acetaminophen at doses equal or less than 4 g/d and with low or normal serum levels of acetaminophen7 (ie, less than would be expected to result in hepatic injury), as was the case for our patient. However, it is recognized that risk factors for acetaminophen toxicity are related to glutathione depletion or relative deficiency (and thus causing 5-oxoproline accumulation due to chronic acetaminophen ingestion), including old age, pregnancy, malnutrition, a vegetarian diet, sepsis, multiple chronic illnesses, and chronic kidney disease.8 Some other medications have also been implicated, including netilmicin, flucloxacillin, and vigabatrin.9

Treatment with N-acetylcysteine has been used in several case reports, as it has been shown to restore glutathione levels in patients with hereditary 5-oxoprolinuria.10 Glutathione inhibits the gamma-glutamyl cysteine synthetase and decreases the formation of 5-Oxoproline.

It is important to note that acetaminophen is probably the most widely used drug in the world.11 At the same time, it is probably one of the most dangerous compounds in medical use, causing hundreds of deaths in all industrialized countries due to acute liver failure in the setting of acute overdose.12 There are other potential safety issues related to acetaminophen at therapeutic doses,13 including a dose response increase in the relative rates of adverse cardiovascular events (small increase in blood pressure, coronary heart disease, stroke), thrombocytopenia, agranulocytosis, nephrotoxicity, hypersensitivity reactions, gastrointestinal complaints, drug interactions with warfarine.12,13 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis assessed the possible association between acetaminophen use and renal impairment.14 Participants without a history of renal impairment who used acetaminophen were found to have an increased risk of renal impairment compared with no use (adjusted odds ratio = 1.23, 95% confidence interval, 1.07-1.40). However, a high degree of study heterogeneity was observed.14 Furthermore, regarding the doses of acetaminophen and the incidence of adverse effects, a striking trend of dose response was observed between acetaminophen at standard analgesic doses and adverse events that are often observed with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including an increasing incidence of mortality, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and renal adverse effects in the general population.13

An important question related to the case that is reported here is whether or not this incident could have been prevented. Based on the literature, lowering the dose or even stopping the administration of acetaminophen in a fragile patient with risk factors of acetaminophen toxicity would have likely prevented this issue. The patient received the maximum therapeutic dose (4g/d) during several weeks while she was malnourished, with sepsis and multiple organ failure. Many of these factors are associated with depletion of glutathione stores as discussed above. The ideal dose of acetaminophen in critically ill patients is not known but it should generally be lowered to 2 to 3 g/d as these patients have many of the risk factors of toxicity. This dose range is also recommended in elderly patients and those that weigh less than 50 kg.15

d-Lactic Acidosis

In our patient, d-lactate was another potential cause of HAGMA. There are two known sources of d-lactate, one is from colonic carbohydrate-fermenting bacteria and the second involves production in the intestinal epithelial cells via the methylglyoxal pathway. The latter involves convertion of glucose into methylglyoxal and then to d-lactate by the d-lactate dehydrogenase.16 The excessive intake of glucose by a cell activates the methylglyoxal pathway. Certain risk factors predispose to this condition including short gut (causing carbohydrate malabsorption and increased distal delivery of glucose), accumulation of colonic bacterial flora (that produce d-lactic acid), and decreased colonic motility (which increases fermentation time).17 Management of d-lactate includes antimicrobials, low-carbohydrate diet, alkali therapy, dialysis, and surgical intestinal lengthening.

The d-lactate level in our patient was low; however, the blood sample was collected after her first SLED treatment and the timing of collection may be important.18 Regardless, the clinical picture overall was more consistent with our patient’s HAGMA being related primarily to 5-oxoproline accumulation.

In conclusion, even patients assessed during the course of a prolonged hospitalization may become vulnerable to rare causes of HAGMA. After considering the usual suspects, additional evaluations, special testing, and treatments may be required for the rarer causes of HAGMA for which routine testing is not typically available. Considering these entities is important as doing so can guide potentially lifesaving treatments.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the patient’s family who consented to us reporting this case despite the most difficult of circumstances.

Footnotes

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: For the reported case, the patient could not be approached to give consent as she died while in hospital and before we decided to present her history. The patient’s family subsequently provided consent for reporting this case.

Consent for Publication: All authors provided consent for publication.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Ana Cecilia Farfan Ruiz—none; Sriram Sriperumbuduri—none; Julie L V Shaw—none; Edward G Clark—Editorial Board of CJKHD. All authors declared no competing interest.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Patient Perspective: Unfortunately, the patient died 180 days after her initial admission due to recurrent aspirations while on the ward.

ORCID iDs: Ana Cecilia Farfan Ruiz  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7488-5644

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7488-5644

Edward G. Clark  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6767-1197

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6767-1197

References

- 1. Mehta AN, Emmett JB, Emmett M. GOLD MARK: an anion gap mnemonic for the 21st century. Lancet. 2008;372(9642):892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Duewall JL, Fenves AZ, Richey DS, Tran LD, Emmett M. 5-Oxoproline (pyroglutamic) acidosis associated with chronic acetaminophen use. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2010;23(1):19-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fenves AZ, Kirkpatrick HM, III, Patel VV, Sweetman L, Emmett M. Increased anion gap metabolic acidosis as a result of 5-oxoproline (pyroglutamic acid): a role for acetaminophen. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(3):441-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fenves AZ, Emmett M. Approach to patients with high anion gap metabolic acidosis: core curriculum 2021. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;78(4):590-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Njålsson R, Ristoff E, Carlsson K, Winkler A, Larsson A, Norgren S. Genotype, enzyme activity, glutathione level, and clinical phenotype in patients with glutathione synthetase deficiency. Hum Genet. 2005;116(5):384-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Butera L, Feinfeld DA, Bhargava M. Sex differences in the subunits of glutathione-S-transferase isoenzyme from rat and human kidney. Enzyme. 1990;43(4):175-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kalinoski T. Severe anion gap metabolic acidosis resulting from combined chronic acetaminophen toxicity and starvation ketosis: a case report and literature review. Am J Case Rep. 2022;23:e934410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Emmett M. Acetaminophen toxicity and 5-oxoproline (pyroglutamic acid): a tale of two cycles, one an ATP-depleting futile cycle and the other a useful cycle. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(1):191-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liss DB, Paden MS, Schwarz ES, Mullins ME. What is the clinical significance of 5-oxoproline (pyroglutamic acid) in high anion gap metabolic acidosis following paracetamol (acetaminophen) exposure? Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2013;51(9):817-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Humphreys BD, Forman JP, Zandi-Nejad K, Bazari H, Seifter J, Magee CC. Acetaminophen-induced anion gap metabolic acidosis and 5-oxoprolinuria (pyroglutamic aciduria) acquired in hospital. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46(1):143-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sharma CV, Mehta V. Paracetamol: mechanisms and updates. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2014;14(4):153-158. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brune K, Renner B, Tiegs G. Acetaminophen/paracetamol: a history of errors, failures and false decisions. Eur J Pain. 2015;19(7):953-965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Roberts E, Delgado Nunes V, Buckner S, et al. Paracetamol: not as safe as we thought? a systematic literature review of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(3):552-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kanchanasurakit S, Arsu A, Siriplabpla W, Duangjai A, Saokaew S. Acetaminophen use and risk of renal impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2020;39(1):81-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Freo U, Ruocco C, Valerio A, Scagnol I, Nisoli E. Paracetamol: a review of guideline recommendations. J Clin Med. 2021;10(15):3420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bianchetti DGAM, Amelio GS, Lava SAG, et al. D-lactic acidosis in humans: systematic literature review. Pediatr Nephrol. 2018;33(4):673-681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Seheult J, Fitzpatrick G, Boran G. Lactic acidosis: an update. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2017;55(3):322-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weemaes M, Hiele M, Vermeersch P. High anion gap metabolic acidosis caused by D-lactate: mind the time of blood collection. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2020;30(1):011001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]