Abstract

Objective:

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Rehabilitation 2030 initiative is working to develop a set of evidence-based interventions selected from clinical practice guidelines for Universal Health Coverage. As an initial step, the WHO Rehabilitation Programme and Cochrane Rehabilitation convened global content experts to conduct systematic reviews of clinical practice guidelines for 20 chronic health conditions, including cerebral palsy.

Data Sources:

Six scientific databases (Pubmed, EMBASE, Scopus, Web of Science, PEDro, CINAHL), Google Scholar, guideline databases, and professional society websites were searched.

Study Selection:

A search strategy was implemented to identify clinical practice guidelines for cerebral palsy across the lifespan published within 10 years in English. Standardized spreadsheets were provided for process documentation, data entry, and tabulation of the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE II) tool. Each step was completed by 2 or more group members, with disagreements resolved by discussion. Initially, 13 guidelines were identified. Five did not meet the AGREE II established threshold or criteria for inclusion. Further review by the WHO eliminated 3 more, resulting in 5 remaining guidelines.

Data Extraction:

All 339 recommendations from the 5 final guidelines, with type (assessment, intervention, or service), strength, and quality of evidence, were extracted, and an International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Functioning (ICF) category was assigned to each.

Data Synthesis:

Most guidelines addressed mobility functions, with comorbid conditions and lifespan considerations also included. However, most were at the level of body functions. No guideline focused specifically on physical or occupational therapies to improve activity and participation, despite their prevalence in rehabilitation.

Conclusions:

Despite the great need for high quality guidelines, this review demonstrated the limited number and range of interventions and lack of explicit use of the ICF during development of guidelines identified here. A lack of guidelines, however, does not necessarily indicate a lack of evidence. Further evidence review and development based on identified gaps and stakeholder priorities are needed.

Keywords: Cerebral palsy, Rehabilitation, Therapeutics

In its first ever world report on disability in 2011, the World Health Organization (WHO) stated that more than 1 billion people worldwide need or could benefit from rehabilitative health services to promote their quality of life and well-being.1 Current projections are that these numbers are increasing with the aging of the global population, the dramatically increased childhood survival rates worldwide, and the rising prevalence of people of all ages surviving with chronic noncommunicable diseases, with the majority of those at need living in lower resource settings.2,3 The WHO defines rehabilitation as “a set of interventions designed to optimize functioning and reduce disability in individuals with health conditions in interaction with their environment” and has long considered rehabilitative services as an essential part of health care, in conjunction with promotive, preventive, curative, and palliative services.4

Based on the belief that access to health care is a right, the achievement of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) is one of the WHO’s current strategic priorities for meeting Sustainable Development Goal 3, which aims to “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.”5(p.2205) The aim of UHC is that “all people receive quality health services that meet their needs without being exposed to financial hardship in paying for these services.” In February 2017, the WHO hosted Rehabilitation 2030: A Call to Action to strengthen access to rehabilitation through their inclusion in UHC. The ultimate goal is to develop a Package of Interventions for Rehabilitation (PIR) recommended for inclusion in UHC to strengthen rehabilitation planning and services at national and subnational levels, as described in more detail in a recent article.5

Identification of the initial set of 20 health conditions was the first step in this process and was performed using existing data on global burden of disease as well as expert opinion solicited from a large group of multidisciplinary rehabilitation professionals, with at least 1 person representing each relevant discipline, from multiple world regions, with final determinations made by the WHO. Next, for each health conditions selected, small technical working groups (TWG) with a minimum of 3 content experts were formulated and charged with the task of identifying all high quality clinical practice guidelines within each condition, forming a matrix that could later be queried by either condition or area of functioning. A rigorous standardized process was established by the WHO Rehabilitation Programme in collaboration with Cochrane Rehabilitation for conducting the search for and review of all available guidelines.

The 3 pediatric-onset conditions selected for inclusion in the initial set are cerebral palsy (CP), autism spectrum disorders, and intellectual disabilities. Each of these broad categories includes children and adults with widely varying etiologies and functional profiles, which makes it challenging when selecting interventions that are applicable to these heterogeneous, and sometimes overlapping, populations. Also, given that these disorders start early in life, and prior to birth in some cases, the classic definition of rehabilitation as restoring function to a previously more optimal state is not applicable. However, the WHO definition of rehabilitation includes interventions that optimize function without specifying a prior baseline state, so developmental disorders are included in this. Restoring function is also not mentioned in the WHO definition. Intervening with children early in life and their families can serve to enhance functioning and well-being, so this is essentially promotive or preventive rather than restorative.

CP describes a group of permanent disorders of the development of movement and posture, causing limitation in activity.6 This definition incorporates aspects of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)7 model and emphasizes the importance of participation and the role of contextual factors, such as personal characteristics and the environments in which people live. Although advances have been made in the diagnosis and treatment of CP in the past few years, improving access to high quality services across the world requires efforts toward identifying or developing evidence-informed clinical practice recommendations that are available to health care professionals, families, and others involved in managing and delivering these services.

The primary objective of this article is to present the results for guideline identification, evaluation, and extraction for the health condition of CP across all relevant functional domains and across the lifespan of an individual living with CP. Toward this end, each recommended intervention within the guidelines for CP and for each of the other selected health conditions would then be linked to a functional domain to create a matrix of health condition by functional goal. It is anticipated that some interventions (eg, spasticity management) and goals (eg, improving mobility) may be similar across multiple conditions, whereas others may be unique to a specific condition. It is important to note that the decision by the WHO and Cochrane Rehabilitation to initially search for guidelines rather than perform a systematic review of all intervention studies for each condition was based on the rationale that these ideally use the best evidence where available, but may also include expert opinion to supplement the recommendations and minimize the care gaps where evidence is still lacking. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive and systematic guideline review for CP and, as such, provides an overview of the currently available health-related recommendations for this population.

Further development steps beyond guideline identification and extraction are currently underway for finalizing the PIR, including prioritizing interventions by both evidence level and clinical importance, identifying gaps where guidelines are not available, conducting more in-depth evidence reviews where indicated, and providing information on the resources associated with the implementation of the interventions, including the needed assistive technologies, workforce, equipment, and consumables. Finally, the PIR is only 1 of 3 keys area of work identified by the WHO Rehabilitation Programme, with the other 2 being a Guide for Action (www.who.int/rehabilitation/rehabilitation-guide-for-action/en/), which is a toolkit for the assessment and strategic planning to integrate rehabilitation services in countries, and a Rehabilitation Competency Framework, which aims to describe the knowledge, skills, and attitudes required to deliver specific rehabilitation interventions. These efforts have the potential to transform the lives of countless individuals across the world and achieve greater equity in the global right to quality affordable health care.

Methods

TWGs

For the TWG charged with reviewing guidelines for each of the 20 initial rehabilitation conditions, the WHO Rehabilitation Programme recruited rehabilitation experts who were required to submit their resumes for consideration and provide details of any possible conflicts or disclosures prior to approval by WHO project leaders. Their aim was to have at least 3 members per group from more than 1 world region and discipline. Training resources included a webinar and a detailed manual of the guideline selection process. Additionally, a standardized set of spreadsheets was provided for data entry and tabulation and interpretation of the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE II)8 scores.

The CP TWG consisted of 3 physiotherapists (D.L.D., E.L., A.C.C.) and a child neurologist (H.F.), all with extensive expertise in the care and scientific study of individuals with CP. The members of the CP TWG were from 3 different countries (United States, 2 regions in Brazil, and Sweden), and all had a high level of English proficiency. Dr Alexandra Rauch was the WHO project leader.

Search strategy

A comprehensive search strategy required that 6 scientific databases (Pubmed, EMBASE, Scopus, Web of Science, PEDro, and CINAHL), Google Scholar, society or foundation websites relevant to CP, and the guidelines databases specified by the WHO were queried. A librarian was consulted to determine the optimal search strategy for the 6 scientific databases. All other searches were performed independently by at least 2 members of the TWG. Professional society or foundation websites searched included the American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine (AACPDM), American Academy of Pediatrics, European Academy of Childhood Disability, European Academy of Pediatrics, American Association of Neurology, Child Neurology Society, Cerebral Palsy Foundation, Cerebral Palsy Alliance, and United Cerebral Palsy. The WHO recommended guidelines databases searched were Guidelines International Network, U.S. National Guideline Clearinghouse, National Institute for Clinical Excellence (UK), Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, National Library for Health Guidelines Database, L’agence Nationale D’accréditation et D’évaluation en Santé, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, Canadian Medical Association Infobase or Clinical Practice Guidelines, New Zealand Guidelines Group, eGuidelines, EBMPracticeNet, WHO Guidelines, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and NHS Evidence.

Inclusion criteria were all guidelines related to rehabilitation in the specified health condition, within the past 10 years, in English, and for both children and adults. Exclusions for the title and abstract review were as follows: not a guideline, guideline developed for other health conditions, not on rehabilitation, and not produced or revised within the past 10 years.

Additional exclusion criteria during full text review included: (1) appeared to present a conflict of interest (eg, was funded by a commercial company), (2) guideline developers failed to complete a conflict-of-interest declaration that explicitly stated that individuals with a conflict of interest had been excluded, and (3) information on the strength of the recommendations was not provided.

Search process

Review of titles and abstracts was done independently by 2 reviewers who then compared results and resolved differences through discussion to come up with a list of articles for full text review. Review of full articles was also done independently by 2 reviewers, with a final list resolved through discussion. Each was then evaluated using the AGREE II instrument by 4 reviewers to determine whether it met criteria for inclusion in the final list. AGREE II is an international tool for assessing the methodological rigor and transparency of practice guideline development and can also be used prospectively in developing high quality guidelines. Nine items (4, 7, 8, 10, 12, 13, 15, 22, and 23) were selected a priori for determining the cutoff threshold. Guidelines were excluded if the average score of the reviewers in any of the items 4, 8, 12, or 22 was below 3 or if the sum of the average scores for all 9 items was less than 45. Any score disagreement of more than 2 points had to be resolved by reexamination of scores and discussion as needed.

The final step was the extraction of all recommendations from each separate guideline, indicating whether or not it was an intervention and, if so, the level of evidence and strength of the recommendation associated with it. Two other possible categories of recommendations were assessments or services. All data were then submitted to the WHO project leader (AR) who reviewed these prior to final acceptance of the guidelines, confirmed and retained all recommendations related to intervention or assessment, added the quality of evidence determinations, and linked each to an ICF category, which includes a label that indicates the ICF component addressed and a code linked to a specific descriptor. ICF components included “b” for body functions, “s” for body structures, “d” for activities and participation, “e” for environment modifications, and “hc” to represent other potential comorbid health conditions.

Results

The scientific database searches were completed by the librarian at the end of December 2018. She compiled a combined Endnote file with duplicates removed by Endnote. The initial library contained 1736 records, with 1181 records remaining after discarding duplicates. However, not all duplicates were successfully eliminated by Endnote and many more were found during the review process. All other searches by members of the TWG were completed by February 1, 2019. Table 1 describes the results of the initial searches prior to duplicate removal or title and abstract review.

Table 1.

Search strategies used for each database or source with the number of citations yielded from each prior to duplicate removal (those with no yield not listed)

| Database or Source | Search Strategy | No. of Citations |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (“cerebral palsy”[tiab] OR “cerebral palsies”[tiab] OR cerebral palsy[mesh] OR “spastic diplegia”[tiab] OR “neonatal stroke”[tiab] OR “perinatal stroke”[tiab]) AND (guideline [tiab] OR guidelines[tiab] OR guideline[publication type]). Filters: published in the last 10 years; English | 248 |

| EMBASE | (‘cerebral palsy’:ti,ab OR ‘cerebral palsies’:ti,ab OR ‘cerebral palsy’/exp/mj OR ‘spastic diplegia’:ti,ab OR ‘neonatal stroke’:ti,ab OR ‘perinatal stroke’:ti,ab) AND (guideline:ti,ab OR guidelines:ti,ab) AND [english]/lim AND [2009–2019]/py | 487 |

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“cerebral palsy” OR “cerebral palsies” OR “spastic diplegia” OR “neonatal stroke” OR “perinatal stroke”) AND TITLE- ABS-KEY (guideline OR guidelines)) AND PUBYEAR > 2008 AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE “English”)) |

584 |

| Web of Science | TOPIC: (“cerebral palsy” OR “cerebral palsies” OR “spastic diplegia” OR “neonatal stroke” OR “perinatal stroke”) AND TOPIC: (guideline OR guidelines). Refined by: LANGUAGES: (ENGLISH), 2009–2018 | 417 |

| PEDro | Used drop down menu to select “‘cerebral palsy’ and ‘practice’ guideline” since 2009, in English | 1 |

| CINAHL | ((MM “Cerebral Palsy”) OR cerebral palsy OR cerebral palsies OR spastic diplegia OR neonatal stroke OR perinatal stroke) AND TI (guideline OR guidelines) ((MM “Cerebral Palsy”) OR cerebral palsy OR cerebral palsies OR spastic diplegia OR neonatal stroke OR perinatal stroke) AND AB (guideline OR guidelines) |

138 |

| Google (advanced) | ‘cerebral palsy’ and ‘guideline’; ‘cerebral palsy’ and ‘guidelines’. Each limited to 10 years. | 8/32 |

| Society/foundation websites: AACPDM | Manual search of all guidelines related to interventions for cerebral palsy in past 10 years | 4 1 |

| AAN | ||

| Guideline databases: GIN AHRQ NICE eGuidelines | Manual search of all guidelines related to interventions for cerebral palsy in past 10 years | 7 1 |

| EBMPracticeNet NHS evidence |

3

2 1 4 |

Abbreviations: AAN, American Association of Neurology; AHRQ, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; NHS, National Health Service; GIN, Guidelines International Network; TI, Title; AB, Abstract.

To expedite the process, we first completed the title and abstract review of the first 4 scientific databases and compared this list of articles to subsequent search results to determine whether any new guidelines emerged.

The PEDro and CiNAHL database searches yielded 1 and 138 citations, respectively, with no new articles or guidelines identified. Google advanced searches using either ‘guideline’ or ‘guidelines’ combined with ‘cerebral palsy’ yielded 8 and 32 results, respectively, with 1 new citation added for full paper review that had been published in January 20199 and thus had not been detected by the librarian search.

Four Care Pathways,10–13 which explicitly stated that these were intended to be clinical practice guidelines, were found on the AACPDM website, 2 of which were not found elsewhere,12,13 and 1 practice parameter related to CP was found on the American Association of Neurology website,14 which had already been identified by its summary article revealed in an earlier search but had been rejected because of insufficient information. The additional information provided on the website allowed this one to be revived. Six of the databases together yielded a total of 18 citations related to CP, all located in prior searches.

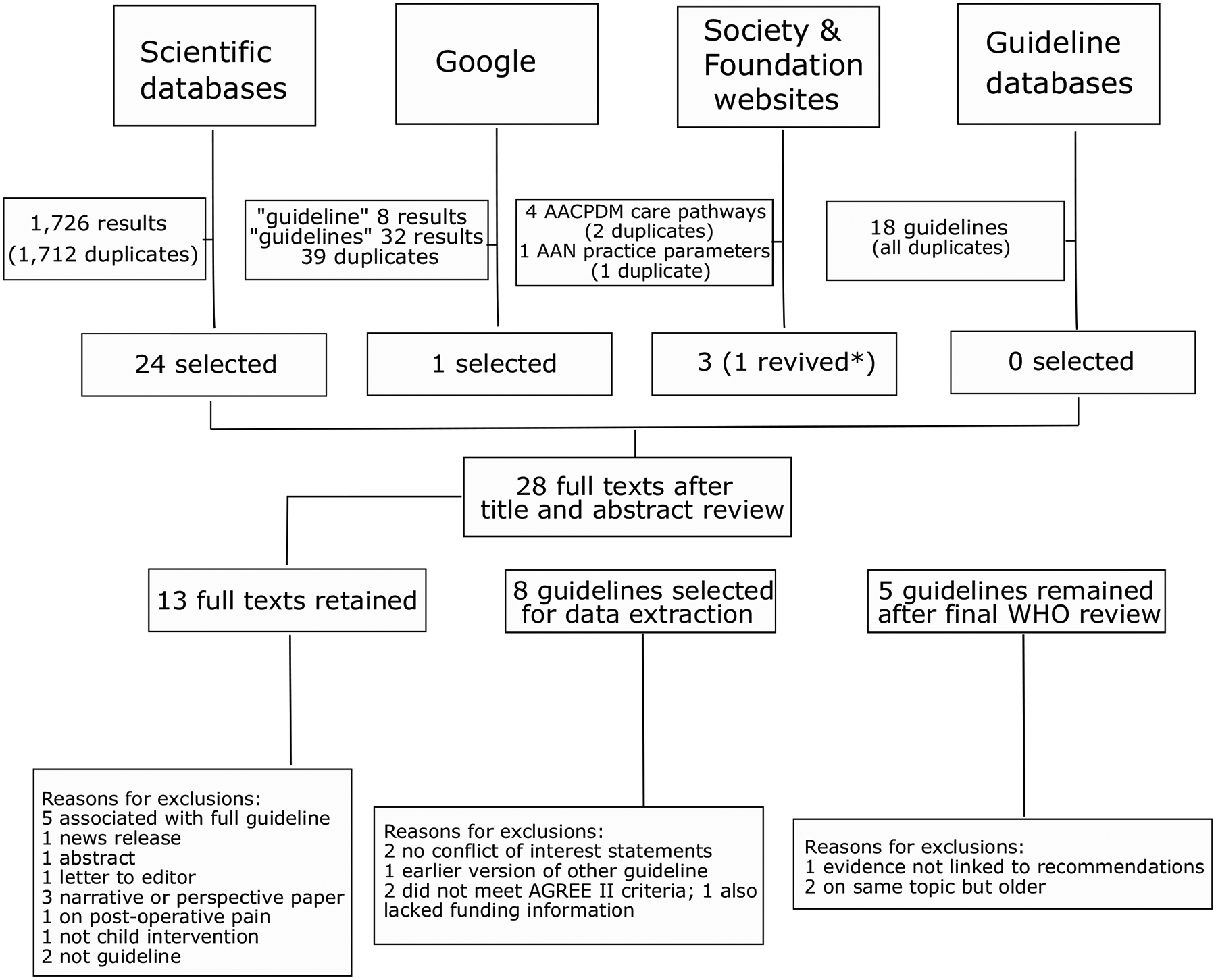

To summarize, after title and abstract review of the scientific database results, 24 articles were identified for full text review. One was added from the Google search and 3 more from society website searches, yielding a total of 28 for full text review. The most common reasons for exclusion during title and abstract review were use of the word guideline in the abstract when it was a systematic review or research study, not specific to CP, or not related to rehabilitation intervention (eg, concerned with screening or diagnosis). Less common exclusions seen in Google and other lay sources included unpublished PhD theses, letters to the editor, policy documents, and those not in English. Figure 1 summarizes the research and review process.

Fig 1.

Flow diagram of database searches and review process.

After full text review, 13 guidelines were identified or retained. Reasons for exclusion at this stage were as follows: 5 were published papers associated with guidelines but not guidelines per se,15–19 1 was a news release,20 1 was an abstract,21 1 was a letter to the editor about a guideline,22 3 were narrative summaries or perspectives,23–25 1 was a tutorial for teachers,26 1 was related to working with parents after diagnosis,27 1 was a systematic review,28 and 1 was on measurement and treatment of acute postoperative pain in CP29 rather than on rehabilitation. The next step was to apply the AGREE II (table 2). Prior to this step, the WHO team instructed us that potential conflicts of interests and disclosures including all funding sources needed to be provided to confirm that there was no external bias in the guideline. Subsequently, 2 citations were removed prior to AGREE II scoring because they did not include conflict of interest or disclosure statements, and these were not available on request (2 of the AACPDM care pathways on hip surveillance and sialorrhea12,13). It was also recognized prior to scoring that the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) document on selective dorsal rhizotomy30 was an interventional procedures guidance, not a guideline, and was thus also excluded. We retained 1 Executive Summary of a guideline during scoring because we were still awaiting funding information from the authors or the society, which led the guideline development and a response on whether the complete guideline was available in English (online version was in Italian).31 Funding information was never received and no English translation was available, so it was subsequently excluded. One other guideline by Verschuren32 did not meet the AGREE II score threshold, so it was eliminated as well, leaving 8 for data extraction. After extraction, all data were submitted to the WHO for review. The WHO subsequently eliminated 3 more guidelines. The hip surveillance guideline33 was excluded because the strength of the evidence was not linked to specific recommendations. The 2 older guidelines on spasticity management were eliminated,14,34 because the similar NICE guideline on this topic35 was more recent and more comprehensive.

Table 2.

AGREE II summary of average scores across 4 reviewers for each criterion with average final scores for 9 key items indicated by shaded regions

| Guideline | Domain 1 Scope and Purpose | Domain 2 Stakeholder Involvement | Domain 3 Rigour of Development | Domain 4 Clarity and Presentation | Domain 5 Applicability | Domain 6 Editorial Independence | Average of 4, 7, 8, 10, 12, 13, 15, 22, and 23 | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | ||

| Italian recommendations | 5 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 33 |

| AAN practice parameter | 7 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 51 |

| NICE: under 25s | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 63 | |

| NICE: adults with CP | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 63 |

| NICE: under 19s | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 60 |

| AACPDM dystonia | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 59 |

| AACPDM osteoporosis | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 59 |

| Exercise and physical activity | 7 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 38 |

| Hip surveillance | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 54 |

| Spasticity | 7 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 50 |

Abbreviation: AAN, American Association of Neurology.

The final 5 guidelines yielded a total of 493 separate recommendations. Those related to service provision (vs “assessment” or “intervention”) were removed. Some recommendations containing several components were separated into 2 or more recommendations and in other cases, very similar recommendations were combined into a single recommendation. Finally, 339 unique recommendations remained, 184 of which were categorized as interventions.

A concise summary of the key recommendations on interventions from each of the 5 guidelines is provided in table 3, along with the level of evidence reported for each. More comprehensive information is available in each specific guideline. Some guidelines focused mainly on a single topic (eg, spasticity management3). In a few cases, recommendations were provided by age group (eg, adults9). More specific details on administration of some recommended medical interventions such as dosages or how to wean or taper medications were not provided in any guidelines. To qualify for inclusion, all were required to provide the scientific evidence for the recommendations, ideally linked to each individually. However, an exception was made for the NICE guidelines, which used a different approach. For the NICE guidelines, the wording indicated the level of evidence (eg, “offer” or “do not offer”) was used when there was strong evidence supporting that recommendation and “consider” was used when the evidence was weak. The remainder were those based on weaker evidence and/or on expert opinion. Some guidelines graded each recommendation for which evidence was available using the following system: A, B, C, or U for unacceptable. Level A (established as effective⁄ ineffective) required at least 2 consistent class I studies; level B (probably effective/ineffective) required at least 1 class I study or at least 2 consistent class II studies; and level C (possibly effective/ineffective) required at least 1 class II study or at least 2 consistent class III studies. Level U (data inadequate or conflicting) resulted when studies did not meet class I, II, or III requirements or included studies that were conflicting.

Table 3.

Data extraction from the final set of 5 guidelines with a summary of interventions with supporting evidence from each

| Guideline | No. of Guidelines | Outcomes Addressed | Summary of Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| NICE: cerebral palsy in adults | 103 | Spasticity Motor function |

|

| NICE: spasticity under 19s | 117 | Spasticity Motor function |

|

| AACPDM care pathway: dystonia | 9 | Muscle tone |

|

| AACPDM care pathway: osteoporosis | 5 | Bone mineral density (fracture risk) |

|

| NICE: assessment and management of CP in the under-25s | 159 | Feeding Communication BMD Drooling Pain Sleep disorders Mental health Postoperative care Comorbidities |

|

Abbreviations: BMD, bone mineral density; CIMT, constraint-induced movement therapy; SDR, selective dorsal rhizotomy; ITB, intra-thecal baclofen; PT, physical therapy; GMFCS, Gross Motor Function Classification System; BotA, Botulinum Toxin A; DBS, deep brain stimulation; CA, calcium.

Linking the targets of the interventions identified from the recommendations to the ICF

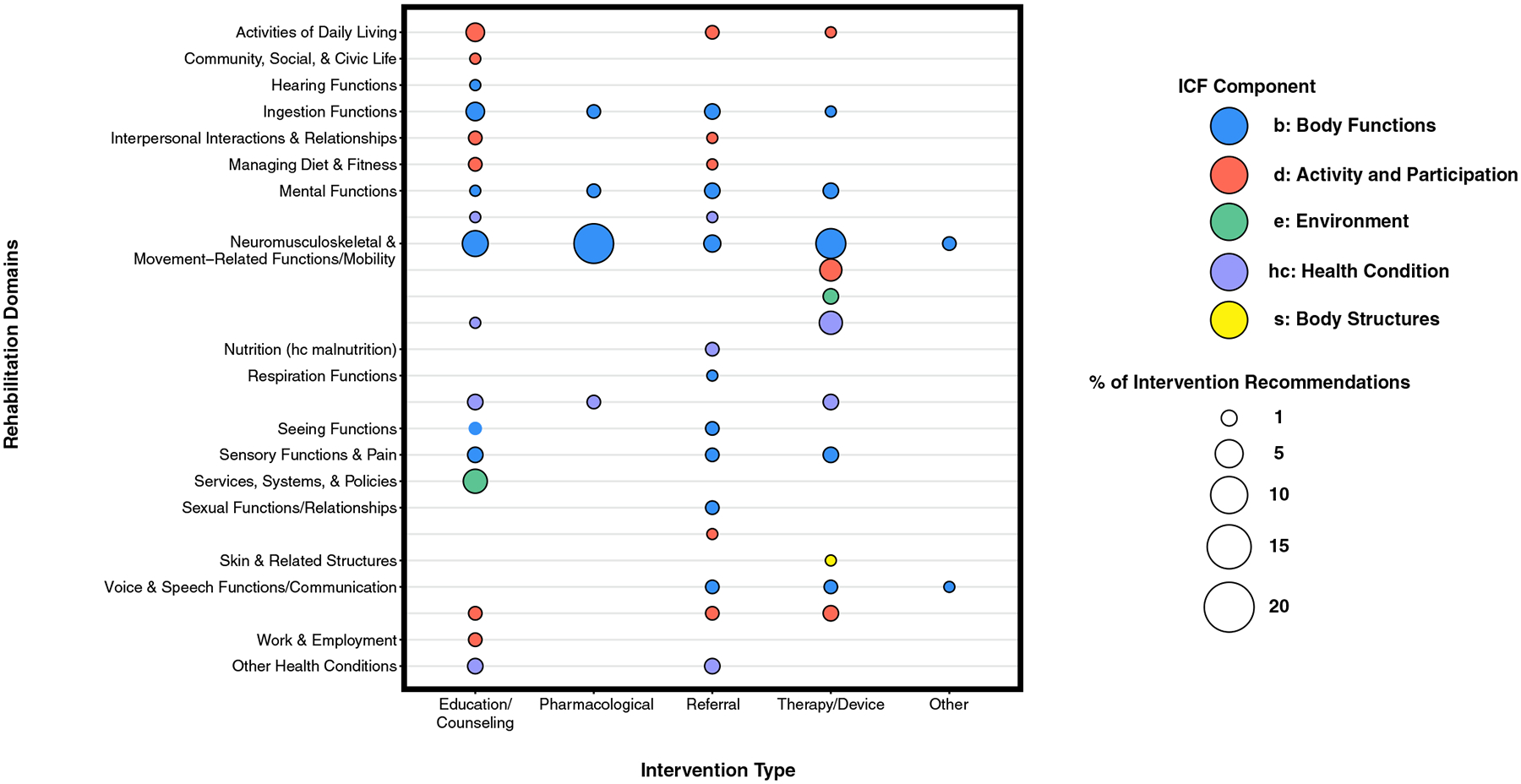

Each of the 184 individual recommendations for interventions was then categorized by the aspect of functioning to which it related. The most populated domain was Neuromusculoskeletal and Movement-related Functions and Mobility (48.4%). However, recommendations spanned many different domains of functioning, including in order of number of recommendations: Voice and Speech, and Communication (6.5%); Mental Functions (6.0%); Ingestion Functions (6.0%); Services, Systems, and Policies (5.4%); Respiration Functions (4.9%); Sensory Functions and Pain (4.3%); Seeing Functions (2.2%); Sexual Functions (1.6%); Interpersonal Interactions and Relationships (1.6%); Managing Diet and Fitness (1.6%); Nutrition (1.1%); Work and Employment (1.1%); Hearing Functions (<1.0%); Skin and Related Structures (<1.0%); Community, Civic, and Social Life (<1.0%); and Bowel and Bladder (only assessments).We further categorized each intervention by type, including referral to expert (17.4%), pharmacologic (21.2%), provision of therapy or device (29.3%), education or counseling (29.3%), or other (1.6%) and by ICF component (see fig 2): body structure or functions (61.0%), activities and participation (17.0%), environmental modifications (7.1%), or health condition (14.7%). These breakdowns are illustrated by functional domain in figure 3. The vast majority of interventions were in the ICF component of body functions with pharmacologic interventions for muscle tone functions the most prevalent single intervention grouping across all categories (18.0% of total). Direct therapy or device provision and educational recommendations were equally prevalent, together compromising nearly 60% of all recommendations.

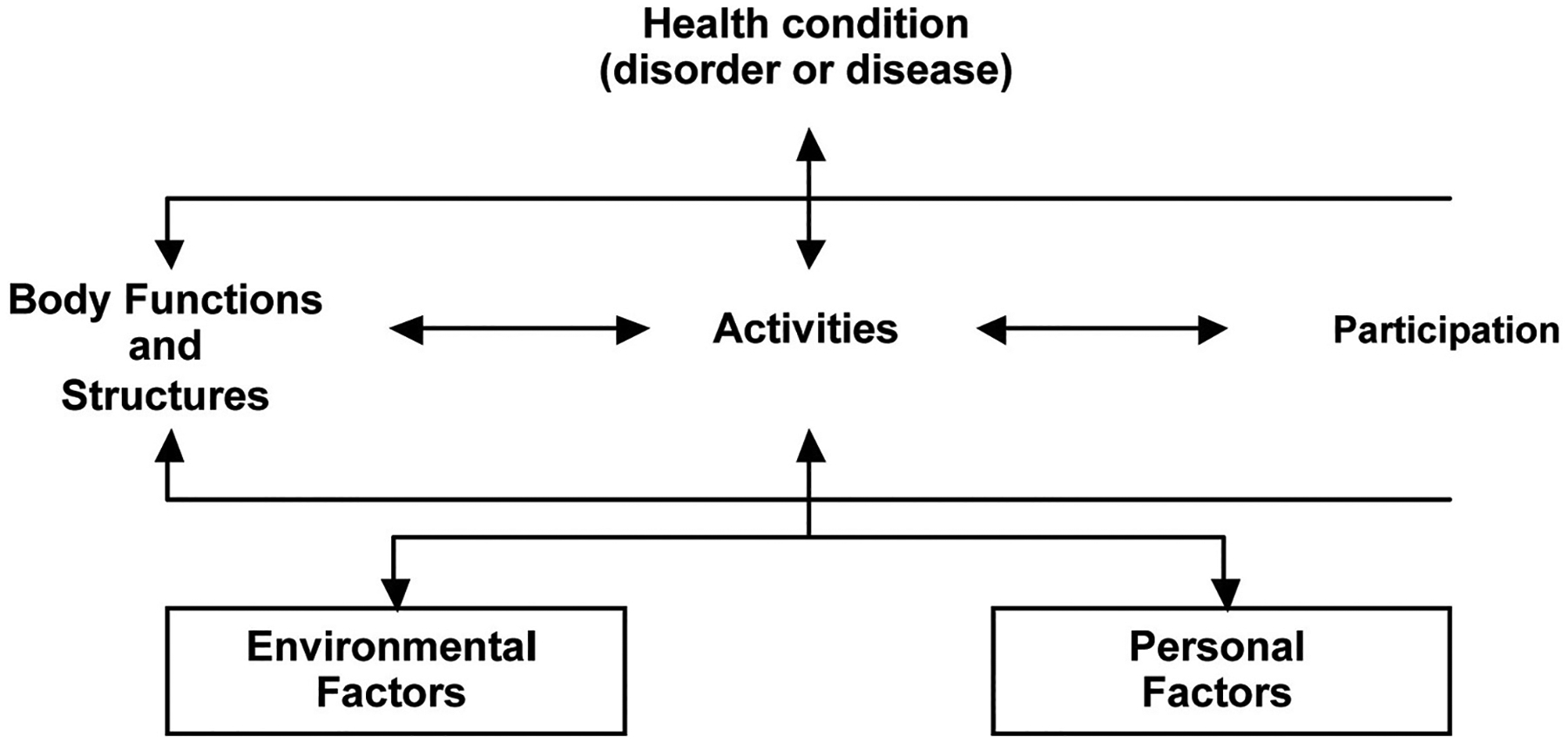

Fig 2.

ICF categories and their interactions.

Fig 3.

Mapping intervention recommendations to the ICF categories.

Discussion

CP is the most prevalent childhood-onset motor disorder diagnosis. It starts very early in fetal or infant development, activity and participation restrictions persist and may even worsen throughout one’s lifespan, and the level of disability on average is fairly high. It was reported at the Rehabilitation 2030 second annual meeting at the WHO in Geneva in July 2019 that CP has the highest global burden of disease among all of the noncommunicable chronic diseases evaluated because of its prevalence, the fact it starts so early in life, and its level of severity. Although high quality data from many highly populated lower resource countries are for the most part either not available or flawed, there is reason to suspect that these data would demonstrate similar if not greater burden estimates.36,37 Because rehabilitation can have a significant and positive effect on the wellbeing and quality of life for individuals with CP and their families, the WHO has made this a global priority when advocating for UHC.

Despite the great need for high quality guidelines, this review demonstrated the somewhat limited number, type, and potential functional effect on activity and participation of interventions mentioned across those guidelines identified here. One of the initial instructions for the TWGs was not to include medical and surgical interventions, not to include interventions aimed primarily at prevention of the health condition, and to focus mainly on therapeutic interventions for different aspects of functioning (eg, motor, cognitive, communication, and emotional/behavioral). Our TWG was concerned that it may be difficult to isolate information on and evidence for certain intervention categories due to the multidisciplinary nature of care in pediatric neurodevelopmental disorders. A program of care is typically recommended that may involve concurrent or sequential delivery of multiple interventions. It must also be recognized that some interventions aim not to improve function in the short term, but rather to prevent worsening or later deformity or disability. We were particularly struck by the dominance of the treatment of spasticity, which was addressed primarily in 3 of the scored guidelines, 2 of which were subsequently eliminated from the summary by the WHO due to duplication. This was further evident in the combined data from the included guidelines in which more than a third of all interventions in the Neuromusculoskeletal and Movement-related Domain addressed tone medications. A general conclusion from these was that for several interventions targeting body functions, reliable evidence is available (eg, adductor botulinum toxin injections for decreasing spasticity) but few have evidence that they improve functioning at the level of activity and participation. Only drugs, including oral medication as well as intrathecal baclofen and injections of botulinum toxin A, which notably can also be used to treat dystonia, or surgical sectioning of dorsal roots, can effectively reduce spasticity with some currently used treatments (eg, phenol and alcohol) not supported by evidence. The addition of adjunctive therapies such as orthoses, casting, stretching and strengthening, or targeted motor training to botulinum toxin had an unacceptable level to support increased effectiveness or efficacy in these guidelines. However the more recent evidence review by Novak et al38 demonstrated that botulinum toxin combined with occupational therapy and other interventions may reliably improve movement functions with still no evidence supporting improvements in self-care from medical or surgical tone management.

Evidence was not provided to support or not support orthopedic surgery, although it was presented as a general option in several instances with no details provided on specific procedures or their indications and at what ages or in which children. Only a few recommendations were made for selective dorsal rhizotomy, which were to consider it only if all other less invasive spasticity interventions are not successful and only for those who ambulate with difficulty (typically described as those in Gross Motor Function Classification System levels II and III, with I being those most functional and V being those with no independent mobility). Given the high prevalence in CP, invasiveness and the associated high costs of surgical interventions, more specific guideline development for these surgical options seems imperative.

The 3 NICE guidelines9,30,39 were the most comprehensive and the 2 more recent ones address important and understudied rehabilitation targets in CP: the multiple comorbidities in CP3 and recognizing the rehabilitation needs of adults with CP.9 Although the hallmark of CP is a motor disability, it is only one of many challenges that individuals with CP may face and may not even been the predominant one for many.6 In particular, communication and eating difficulties, drooling, sleep disorders, mental status changes, and pain are all common and important considerations in this population that can greatly affect daily functioning, participation, and quality of life. Maintaining functioning in adulthood is particularly challenging and, although the same interventions were recommended for consideration in adults as were mentioned for younger children, scientific evidence of their effectiveness in adulthood compared to earlier in life is largely unavailable. The importance of maintaining physical activity was one recommendation for this population that has some support in the adult literature.40

Even though family and child goals tend to be focused on activities and participation, the greatest percentage of interventions were directed at the ICF body functions component, with less than one-third as many directed at activity and participation. As highlighted in a recent narrative review on current management of CP,41 the 6 “F” words42 have provided a novel framework targeted specifically toward the ICF components of activity and participation to help families and clinicians when developing intervention goals in the key areas of importance for children: function, family, fitness, fun, friends, and future. This perspective is important to keep in mind when evaluating the effectiveness of an intervention directed at a body structure or function. If an intervention fails to enhance the quality of life, activity, or participation for that child or family either in the short or longer term, is it justifiable? New ways of thinking can transform care of individuals with disabilities, not just new interventions. The ICF further emphasizes that people may experience disability due to environmental barriers in relation to a health condition, so it is disappointing, to say the least, that no environmental recommendations were included in any guidelines under movement-related functions or mobility. Our world, including homes, communities, schools, and play areas could be designed to be far more accessible to all, which could greatly reduce the physical challenges individuals with CP face when trying to navigate their worlds and enhance their participation. The limited focus on activity and participation in the available guidelines was also remarkable and should demand far greater attention. Each of the guidelines was published well since the establishment of the ICF and the publication of a 2008 article specifically applying the ICF to rehabilitation,43 making the lack of explicit use of the ICF framework hard to understand.

Surprisingly, no identified guideline was focused primarily on physical or occupational therapies, even though these are the major and the most prevalent services delivered in most settings that provide rehabilitation. The one guideline by Verschuren et al32 that was eliminated by the AGREE II threshold provided some useful physical activity recommendations for those with CP but had not been produced through a more formal guideline development process. The only therapies named in some of the other guidelines were physical therapy to actively stretch muscles during everyday activities, constraint-induced movement therapy, bimanual training, and muscle strengthening. Early intervention was only mentioned specifically in the context of improving communication outcomes. The lack of guidelines does not necessarily indicate a lack of evidence. In 2013, and expanded and revised in 2019, Novak et al published a systematic review of systematic reviews on interventions in CP.37,44 The more recent article38 found 118 more interventions in the 6-year span than the 64 identified in the earlier review, demonstrating the rapidly increasing body of evidence. The interventions, 141 of which were on managing care for CP, had a similar breadth and proportional distribution across functional categories and ICF domains as these guideline results, with 62% related to body functions and 16% related to activities and participation (our results were 61% and 17%, respectively). Nearly 60% were on allied health interventions and 20% on pharmacologic ones, again nearly identical to our results. Surgical interventions were more numerous in their report than in the guideline at 13% of the total. However, the referral category in the guidelines included many to surgical specialties. Although the evidence base is clearly improving, the authors concluded that “there is a lack of robust clinical efficacy evidence for a large proportion of the interventions in use within standard care”38(p.13) for CP. This implies that current treatments may not be consistent with the best evidence and/or that clinical judgment, which may vary considerably across practitioners and settings, is still too often used to fill existing gaps until more research data are available.

Translation to lower resource countries

The PIR will ultimately include other important information beyond a set of interventions deemed “essential” linked to scientific evidence of effectiveness or efficacy. The numbers of individuals, the extent to which they might be positively affected by a specific intervention, and the costs associated with assistive technologies and equipment, as well as resources in terms of qualified health care staff, are also important considerations when selecting interventions across widely divergent settings.

Although surgical and other costly medical interventions were recommended in the reviewed guidelines, there was no mention of therapies that use more expensive types of instrumentation to improve movement functions such as body-weight supported treadmills or robot-assisted gait trainers, which are present in many rehabilitation settings, or devices such as electrical stimulation devices. Computer or virtual reality training systems or wearable exoskeletons are rapidly emerging technologies for rehabilitation. Given the higher cost and workforce requirements of technologies, supporting evidence showing their superiority over those with lower costs and greater ease and accessibility must be provided as part of any future recommendation that may be advocating for their use.

In concert with identifying knowledge gaps, greater efforts must be made to engage stakeholders in identifying specific research or guideline development priorities that would be most effective for enhancing the lives of those with CP.

Study limitations

The guideline search is only the beginning of the process of identifying and evaluating existing evidence for clinical practice and, as such, is not expected to cover all aspects of care in CP. It does provide a comprehensive evaluation of all published high quality clinical practice guidelines for those who are seeking these to guide policy or clinical practice or to researchers who are seeking to fill in the gaps.

Conclusions

Determination of what is considered high quality yet affordable health care are is a major topic of debate across all conditions and types of medical care from primary to palliative. The final list of interventions selected for the PIR may ultimately need to be prioritized by users depending on factors such as specific country needs and resources, the magnitude of the effects they have on health and well-being, and consideration of associated costs, among others. Among chronic noncommunicative disorders, CP purportedly has the highest global burden and therefore has a great need for effective rehabilitative therapies. This clinical practice guideline review process is an important first step of many to follow. Existing guidelines are largely insufficient in scope and detail, with the lack of therapy guidelines most notable. Efforts to develop more detailed recommendations tailored to the appropriate age ranges and functional levels and with dose estimates for producing clinically significant effects would greatly enhance their clinical utility. Finally, further systematic evidence reviews are needed to fill recommendation gaps and, where key evidence is lacking, to help prioritize future clinical research efforts.

Acknowledgments

We thank Audrey Thurm, Ph.D. and Jordan Wickstrom, Ph.D. at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for their help in the initial phases of this work and Jordan Wickstrom at NIH and Tonya Piergies, B.A. at University of California San Francisco for designing the ICF figure.

Supported in part by the Intramural Research Program at the NIH Clinical Center.

List of abbreviations:

- AACPDM

American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine

- AGREE II

Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation

- CP

cerebral palsy

- ICF

International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health

- NICE

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- PIR

Package of Interventions for Rehabilitation

- TWG

technical working group

- UHC

Universal Health Coverage

- WHO

World Health Organization

Footnotes

Disclosures: none.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. World Report on Disability. Available at: www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/en. Accessed February 2, 2021.

- 2.Kamenov K, Mills JA, Chatterji S, Cieza A. Needs and unmet needs for rehabilitation services: a scoping review. Disabil Rehabil 2019;41: 1227–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rifkin SB. Alma Ata after 40 years: Primary health care and health for all-from consensus to complexity. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3(Suppl 3): e001188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Rehabilitation in health systems. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254506/9789241549974-eng.pdf?sequence=8. Accessed February 2, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rauch A, Negrini S, Cieza A. Toward strengthening rehabilitation in health systems: methods used to develop a WHO package of rehabilitation interventions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2019;100: 2205–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenbaum P, Paneth N, Leviton A, et al. A report: the definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev Med Child Neurol Suppl 2007;109:8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ 2010;182:E839–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NG119). Cerebral palsy in adults. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng119. Accessed February 2, 2021. [PubMed]

- 10.Fehlings D, Brown L, Harvey A, et al. Dystonia in cerebral palsy. Available at: https://www.aacpdm.org/publications/care-pathways/dystonia. Accessed February 2, 2021.

- 11.Fehlings D, Switzer L, Stevenson R, et al. Osteoporosis in cerebral palsy. ACvailable at: www.aacpdm.org/publications/care-pathways/osteoporosis. Accessed February 2, 2021.

- 12.O’Donnell M, Mayson T, Miller S, et al. Hip surveillance in cerebral palsy. Available at: https://www.aacpdm.org/publications/care-pathways/hip-surveillance. Accessed February 2, 2021.

- 13.Glader L, Delsing C, Hughes A, et al. Sialorrhea in cerebral palsy. Available at: https://www.aacpdm.org/publications/care-pathways/sialorrhea. Accessed February 2, 2021.

- 14.Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society, Delgado MR, Hirtz D, et al. Practice parameter: pharmacologic treatment of spasticity in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology 2010; 74:336–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaplin S. Assessment and management of cerebral palsy in the under-25s. Prescriber 2017;28:41–4. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fehlings D, Switzer L, Agarwal P, et al. Informing evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for children with cerebral palsy at risk of osteoporosis: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol 2012;54: 106–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mugglestone MA, Eunson P, Murphy MS; Guideline Development Group. Spasticity in children and young people with non-progressive brain disorders: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2012;345:e4845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozel S, Switzer L, MacIntosh A, Fehlings D. Informing evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for children with cerebral palsy at risk of osteoporosis: an update. Dev Med Child Neurol 2016;58: 918–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaunak M, Kelly VB. Cerebral palsy in under 25s: assessment and management (NICE Guideline NG62). Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 2018;103:189–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Torjesen I. NICE publishes guideline on diagnosing and managing cerebral palsy in young people. BMJ 2017;356:j462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.AACPDM Sialorrhea Care Pathway Team. Sialorrhea in cerebral palsy. Available at: https://www.aacpdm.org/publications/care-pathways/sialorrhea. Accessed February 2, 2021.

- 22.Whelan MA, Delgado MR. Practice parameter: pharmacologic treatment of spasticity in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy (an evidence-based review): report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American academy of neurology and the practice committee of the child neurology society. Neurology 2010;75:669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dean E. Cerebral palsy. Nurs Stand 2017;31:15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones KB, Wilson B, Weedon D, Bilder D. Care of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: cerebral palsy. FP Essent 2015;439:26–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verschuren O, Ada L, Maltais DB, Gorter JW, Scianni A, Ketelaar M. Muscle strengthening in children and adolescents with spastic cerebral palsy: considerations for future resistance training protocols. Phys Ther 2011;91:1130–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costigan FA, Light J. Functional seating for school-age children with cerebral palsy: an evidence-based tutorial. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch 2011;42:223–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higginson J, Matthewson M. Working therapeutically with parents after the diagnosis of a child’s cerebral palsy: issues and practice guidelines. Aust J Rehabil Couns 2014;20:50–66. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monge Pereira E, Molina Rueda F, Alguacil Diego IM, et al. Use of virtual reality systems as proprioception method in cerebral palsy: clinical practice guideline. Neurologia 2014;29:550–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sabourdin N Pain management in children with cerebral palsy (Chapter 27). In: Canavese F, Deslandis J, editors. Orthopedic management of children with cerebral palsy: a comprehensive approach. Waltham: Nova Biomedical; 2015. p 581–96. BISAC: MED069000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (IPG373). Selective dorsal rhizotomy for spasticity in cerebral palsy. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/IPG373. Accessed February 2, 2021.

- 31.Castelli E, Fazzi E. Recommendations for the rehabilitation of children with cerebral palsy. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2016;52:691–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verschuren O, Peterson MD, Balemans AC, Hurvitz EA. Exercise and physical activity recommendations for people with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 2016;58:798–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wynter M, Gibson N, Kentish M, Love S, Thomason P, Kerr Graham H. The consensus statement on hip surveillance for children with cerebral palsy: Australian standards of care. J Pediatr Rehabil Med 2011;4:183–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Love SC, Novak I, Kentish M, et al. Botulinum toxin assessment, intervention and after-care for lower limb spasticity in children with cerebral palsy: international consensus statement. Eur J Neurol 2010; 17(Suppl 2):9–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (CG145). Spasticity in the under 19’s. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG145. Accessed February 2, 2021.

- 36.Damiano D, Forssberg H. Poor data produce poor models: children with developmental disabilities deserve better. Lancet Glob Health 2019;7:e188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kakooza-Mwesige A, Andrews C, Peterson S, Wabwire Mangen F, Eliasson AC, Forssberg H. Prevalence of cerebral palsy in Uganda: a population-based study. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:e1275–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Novak I, Morgan C, Fahey M, et al. State of the evidence traffic lights 2019: systematic review of interventions for preventing and treating children with cerebral palsy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2020;20:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NG62). Cerebral palsy in under 25s. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng62. Accessed February 2, 2021. [PubMed]

- 40.Bottos M, Feliciangeli A, Sciuto L, Gericke C, Vianello A. Functional status of adults with cerebral palsy and implications for treatment of children. Dev Med Child Neurol 2001;43:516–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Graham D, Paget SP, Wimalasundera N. Current thinking in the health care management of children with cerebral palsy. Med J Aust 2019; 210:129–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenbaum P, Gorter JW. The ‘F-words’ in childhood disability: I swear this is how we should think! Child Care Health Dev 2012;38: 457–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rauch A, Cieza A, Stucki G. How to apply the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) for rehabilitation management in clinical practice. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2008;44: 329–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Novak I, McIntyre S, Morgan C, et al. A systematic review of interventions for children with cerebral palsy: state of the evidence. Dev Med Child Neurol 2013;55:885–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]