Abstract

Background

In 2020, Mexico experienced one of the highest rates of excess mortality globally. However, the extent of non-COVID deaths on excess mortality, its regional distribution and the association between socio-demographic inequalities have not been characterized.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective municipal and individual-level study using 1 069 174 death certificates to analyse COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 deaths classified by ICD-10 codes. Excess mortality was estimated as the increase in cause-specific mortality in 2020 compared with the average of 2015–2019, disaggregated by primary cause of death, death setting (in-hospital and out-of-hospital) and geographical location. Correlates of individual and municipal non-COVID-19 mortality were assessed using mixed effects logistic regression and negative binomial regression models, respectively.

Results

We identified a 51% higher mortality rate (276.11 deaths per 100 000 inhabitants) compared with the 2015–2019 average period, largely attributable to COVID-19. Non-COVID-19 causes comprised one-fifth of excess deaths, with acute myocardial infarction and type 2 diabetes as the two leading non-COVID-19 causes of excess mortality. COVID-19 deaths occurred primarily in-hospital, whereas excess non-COVID-19 deaths occurred in out-of-hospital settings. Municipal-level predictors of non-COVID-19 excess mortality included levels of social security coverage, higher rates of COVID-19 hospitalization and social marginalization. At the individual level, lower educational attainment, blue-collar employment and lack of medical care assistance prior to death were associated with non-COVID-19 deaths.

Conclusion

Non-COVID-19 causes of death, largely chronic cardiometabolic conditions, comprised up to one-fifth of excess deaths in Mexico during 2020. Non-COVID-19 excess deaths occurred disproportionately out-of-hospital and were associated with both individual- and municipal-level socio-demographic inequalities.

Keywords: Excess mortality, inequalities, social lag, COVID-19, Mexico

Key Messages.

Mexico experienced one of the highest rates of excess mortality in Latin America following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic but the extent to which non-COVID-19 deaths contributed to excess mortality has not yet been characterized.

We conducted a retrospective, municipal and individual-level study using data from 1 069 174 death certificates to estimate mortality related to COVID-19 and to non-COVID-19 causes using ICD-10 codes in 2020 compared with 2015–2019.

There was a 51% higher mortality rate in 2020 compared with the 2015–2019 average, largely attributable to COVID-19 deaths (76.1% of cases), which occurred primarily in-hospital; conversely, one-fifth of excess deaths in Mexico in 2020 were attributable to non-COVID-19 causes, largely cardiometabolic conditions, which occurred primarily out-of-hospital.

Southern regions and marginalized communities in Mexico carried a disproportionate burden of excess mortality; municipal-level correlates of these excess deaths included lower healthcare coverage, whereas individual-level factors that correlated with non-COVID-19 mortality included lower educational attainment, blue-collar employment and lack of medical care assistance prior to death.

Excess mortality in Mexico in 2020 was attributed to both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 causes, likely reflecting a complex interplay between a fragmented and under-resourced health system, strained hospital capacity and socio-demographic inequalities further unmasked by the pandemic.

Introduction

Over 6 million deaths attributable to COVID-19 have been reported globally since the onset of the pandemic in early 2020.1 Beyond this devastating death toll, there is increasing recognition of the widespread disruption of the pandemic on healthcare services, with a far-reaching impact on the care of non-COVID-19 conditions.2 Excess mortality has been proposed as a key indicator that captures both deaths caused by COVID-19 and indirect deaths attributed to the pandemic more broadly due to interruption in routine care of chronic conditions.3,4 Notably, many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), particularly in Latin America, were vulnerable to the direct and indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic due to chronic underinvestment in public healthcare.5 Though several reports have estimated that rates of excess mortality were disproportionately higher in LMICs following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is limited insight regarding non-COVID-19 deaths and their contribution to the reported rates of excess mortality in Latin America.6

Mexico is of particular interest given that it ranks as one of the countries with the highest rates of excess mortality in the Latin American region following onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.7 A confluence of health and socio-demographic inequalities that pre-dated the COVID-19 pandemic, a high burden of chronic cardiometabolic conditions and a fragmented healthcare system all contributed to a high and disproportionate burden of excess mortality among marginalized communities.5,8 A descriptive assessment performed in Mexico showed that chronic cardiometabolic conditions, which are highly prevalent among communities of low socio-economic status, were the main causes of death independently of registered COVID-19 deaths in Mexico during 2020.9 However, whether hospital saturation had ripple effects on out-of-hospital excess mortality, particularly for highly prevalent chronic health conditions across different vulnerable regions, has not yet been characterized. Hence, there is a need to comprehensively assess the extent to which individual- and municipal-wide-level socio-demographic inequalities impacted excess mortality to further guide health policies to strengthen existing systems and mitigate ongoing health disparities.

In this study, we sought to: (i) estimate the age-adjusted rates of cause-specific excess mortality due to COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 deaths in 2020 compared with the 2015–2019 period, stratified by in-hospital and out-of-hospital setting; (ii) evaluate the geographical distribution of cause-specific excess mortality in Mexico in 2020; and (iii) characterize the association between municipal- and individual-level socio-demographic inequality measures and non-COVID-19-related excess mortality.

Methods

Study design and data sources

Based on the work by Lima et al., we conducted a retrospective municipal- and individual-level study using national mortality records from 2015–2019 compared with 2020.6 Death certificate records of individuals living in Mexico were collected by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI). Briefly, INEGI generates annual mortality statistics from death certificates and vital socio-demographic characteristics issued by the Ministry of Health, which includes the primary cause of death in accordance with the tenth version of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10).10 Complete methodology of the death certification process, validation and collected variables are available in the Supplementary material (available as Supplementary data at IJE online).

Variables and definitions

Outcome variables

Cause-specific excess mortality was centred on two primary outcomes: deaths due to COVID-19 and deaths related to non-COVID-19 causes. Overall excess mortality was the sum of excess mortality due to non-COVID-19 causes and all registered COVID-19 deaths.

COVID-19 deaths

Deaths attributable to COVID-19 were defined based on the following ICD-10 codes: U071 (identified SARS-CoV-2), U072 (suspected SARS-CoV-2) and deaths after April 2020 classified as J00–J99 (respiratory deaths). This aggregation of COVID-19 deaths considers inadequate registration of COVID-19 cases across 2020 as there are an unknown number of deaths that could have been classified with unspecified respiratory diseases in the early stages of the pandemic due to limited SARS-CoV-2 testing capacity in Mexico.11

Non-COVID-19 cause-specific mortality

All other causes of death were classified as non-COVID-19-related deaths and were coded using the 2020 Mexican list of mortality, which includes 436 specific causes of death.12 To simplify result presentation, we only display the first 10 cause-specific deaths in the main results, with the full list provided in the Supplementary material (available as Supplementary data at IJE online).

Excess mortality estimation

According to the approach proposed by Karlinsky and Kobak, we estimated excess mortality as the difference between average deaths during the 2015–2019 period compared with deaths registered during 2020.13 We used average deaths for two reasons: (i) the use of average deaths is a simple approach shown to be a reliable assessment based on sensitivity analyses estimations; and (ii) given that we are estimating 436 specific causes of death, predictive methods based on generalized linear models may overestimate the standard error for low-frequency causes.9 Excess deaths were standardized to age-adjusted rates per 100 000 population with age structures by state, municipalities, and regions per 5-year increments using population projections provided by the National Population Council (CONAPO). Percent increase in 2020 compared with 2015–2019 was also used as a proxy of excess mortality.

Stratification by setting of death

We hypothesized that the COVID-19 pandemic posed a significant burden on in-hospital care, which may have influenced increases in excess mortality, particularly for non-COVID-19-related deaths. To evaluate this hypothesis, we stratified excess mortality according to whether the death occurred out-of-hospital or in-hospital, as registered on death certificates. Out-of-hospital deaths were defined accordingly if the death was not registered in a hospital setting or if they were coded as occurring at the deceased person’s home or elsewhere (i.e. in the streets in some instances). Deaths with an unspecified setting were excluded across all the analysis.

Marginalization index

To quantify the impact of municipal socio-demographic inequalities on excess mortality, we used the 2020 municipal social lag index (SLI) estimated by the National Council for Evaluation of Social Development Policy (CONEVAL).14 Since we intended to evaluate social inequalities independently from urbanization and centralized health services, we used residuals of linearly regressed mean urban population density and hospital beds per 100 000 inhabitants using data extracted from CONEVAL to fit an adjusted municipal SLI (aSLI). We then categorized municipalities into four aSLI categories (Low-aSLI, Moderate-aSLI, High-aSLI and Very-High aSLI) based on the Dalenius & Hodges method (Supplementary material, available as Supplementary data at IJE online).

Municipal-level correlates of excess mortality

We included the percentage of the population without healthcare coverage and the hospital occupancy due to COVID-19 inpatients as municipal-level factors related to excess mortality. Healthcare coverage was obtained from 2020 CONEVAL estimations. To estimate a surrogate of hospital occupancy, we used the number of hospitalizations with confirmed COVID-19 from the National Epidemiological Surveillance System (SINAVE) data set collected by the General Directorate of Epidemiology (DGE) of the Mexican Ministry of Health, which includes reports of daily updated suspected COVID-19 cases.15 Complete methodology, the protocol of testing and the variables included are available in the Supplementary material (available as Supplementary data at IJE online).

Statistical analysis

To visualize differences in deaths over time in 2020 compared with the 2015–2019 period, we first plotted excess mortality per 100 000 inhabitants by month of occurrence, stratified by COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 causes. We then disaggregated excess mortality rates due to COVID-19 or non-COVID-19 causes by state and municipality. Next, to visualize whether the proportion of age-adjusted excess mortality in each municipality increased due to COVID-19 or non-COVID-19 causes, we used choropleth maps classified using the quantile method with the biscale R package. We further visualized the relationship between excess mortality and aSLI using the same method. The median value for the estimated age-adjusted excess mortality and the aSLI were considered as the cut-off threshold.

Municipal-level factors associated with excess mortality

Next, we evaluated the impact of municipal characteristics on increased risk of age-adjusted excess mortality using negative binomial regression models to obtain incidence rate ratios (IRRs) (Supplementary material, available as Supplementary data at IJE online). Models were adjusted for municipal male-to-female death ratio, education percentage, access to medical assistance and urbanization (to adjust for residual covariance). We also calculated the ratio of out-of-hospital to in-hospital deaths, which was also adjusted for the above outlined covariates.16 IRRs were plotted using the jtools R Package.

Individual-level factors related to non-COVID-19 mortality

To identify individual-level factors associated with the probability of death attributable to non-COVID-19 causes as compared with COVID-19, we fitted hierarchical random-effects logistic regression models, which included individual- and municipal-level variables (Supplementary material, available as Supplementary data at IJE online). Individual-level variables included sex, education, self-reported indigenous identity, work occupation, access to medical assistance prior to death and social security coverage. We perform a municipal-level adjustment that included living in municipalities with low hospital bed occupancy (<1 bed per 100 000 inhabitants) and municipal aSLI categories. For this model, we used the municipality of death occurrence as a random intercept to account for inter-municipal variability in death registration in the model and to establish a hierarchical relationship between individual- and municipal-level variables. All analyses were performed using R software (Version 4.1.2).

Results

Overall and cause-specific excess mortality in Mexico during 2020

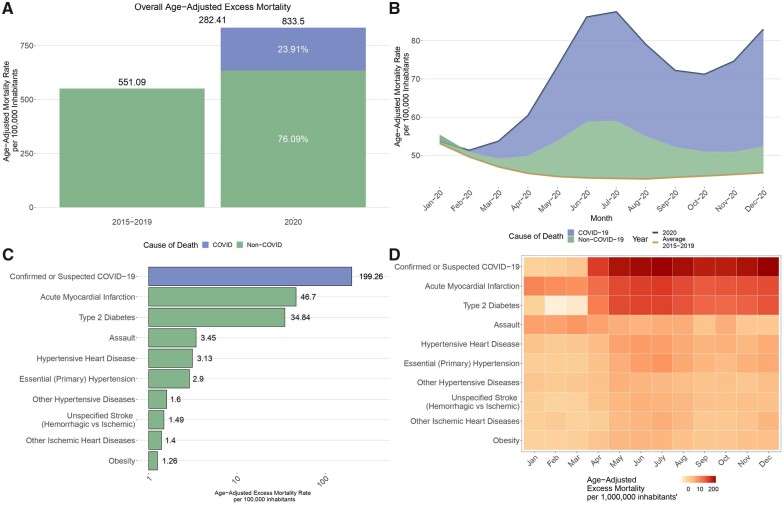

We identified 1 069 174 deaths in Mexico during 2020 compared with 686 567 average deaths in 2015–2019. We estimated an age-adjusted mortality rate of 833.5 deaths per 100 000 inhabitants for 2020, with an estimated age-adjusted excess mortality of 282.41 deaths per 100 000 inhabitants; this represents a 51% increase in mortality compared with the average age-adjusted mortality rates in 2015–2019 (551.09 per 100 000 inhabitants). Peak excess mortality during 2020 was observed during the May-to-June period. Approximately 76.1% of excess deaths were attributable to confirmed or suspected COVID-19, whereas 23.9% were attributable to non-COVID-19 causes. The main contributors of excess mortality were suspected or confirmed COVID-19 deaths (199.26 per 100 000 inhabitants). The five leading causes of non-COVID-19 excess mortality were acute myocardial infarction (46.7 deaths per 100 000 inhabitants), type 2 diabetes (34.84 deaths per 100 000 inhabitants), violent assaults (3.45 deaths per 100 000 inhabitants), hypertensive heart disease (3.13 deaths per 100 000 inhabitants) and essential arterial hypertension (2.9 deaths per 100 000 inhabitants). All excess deaths were recorded after April 2020, with a steep increase after this period for COVID-19, acute myocardial infarction and type 2 diabetes-related deaths (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Age-adjusted mortality rates and excess mortality in Mexico in 2020. (a) Age-adjusted mortality rates in 2020 compared by the average period of 2015–2019. (b) Distribution of excess mortality in Mexico stratified by deaths associated with COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 for the year 2020. (c) Ten main causes of age-adjusted excess mortality in Mexico. (d) Stratification of the 10 main causes of age-adjusted excess mortality by month of occurrence in Mexico

Excess mortality according to in-hospital vs out-of-hospital death

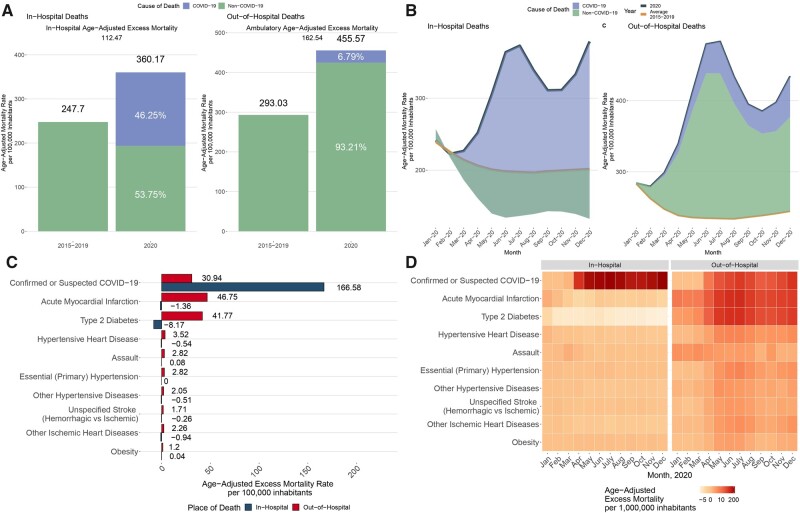

When stratified by the setting of death, we estimated an in-hospital excess mortality rate of 112.47 deaths per 100 000 inhabitants and an out-of-hospital excess mortality rate of 162.54 deaths per 100 000 inhabitants; this represents an increase of 45.4% and 55.5% of in-hospital and out-of-hospital deaths, respectively, compared with the average of 2015–2019. When stratified by the specific cause of death, we observed that excess in-hospital mortality rates were primarily attributable to COVID-19 deaths, whereas there was a decrease for in-hospital non-COVID-19-related deaths after March 2020. An estimated 80.96% of all out-of-hospital excess mortality was attributable to non-COVID-19 causes, whereas only 19.03% were attributable to COVID-19 deaths. Excess deaths attributable to COVID-19 occurred predominantly in the in-hospital setting, whereas most non-COVID-19 deaths occurred largely out-of-hospital (Supplementary Table S1, available as Supplementary data at IJE online). Among the 10 leading causes of excess mortality, acute myocardial infarction and type 2 diabetes decreased in-hospital but increased out-of-hospital after April 2020 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

In-hospital and out-of-hospital age-adjusted mortality rates and excess mortality in Mexico in 2020. (a) Stratification of in-hospital and out-of-hospital age-adjusted mortality rates in 2020 compared with the average period of 2015–2019. (b) Distribution of excess mortality in Mexico stratified death setting and by deaths associated with COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 for the year 2020. (c) Ten main causes of age-adjusted excess mortality stratified by place of occurrence in Mexico. (d) Stratification of the 10 main causes of age-adjusted excess mortality by month and place of occurrence of death in Mexico

Regional state- and municipal-level heterogeneity in COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 excess mortality

When COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 excess mortality was stratified at the state level, Mexico City, Baja California and Chihuahua displayed the highest COVID-19 age-adjusted excess mortality rate, whereas Chihuahua, Mexico City and Chiapas had the highest non-COVID-19 excess mortality rates. There was an unequal distribution of non-COVID-19 age-adjusted excess mortality at the state level, with the southern states of Chiapas, Oaxaca and Michoacan having the highest rates of non-COVID-19-related excess mortality (Supplementary Figure S1, available as Supplementary data at IJE online). Further stratification revealed a geographical aggregation of non-COVID-19 deaths caused by acute myocardial infarction, type 2 diabetes, essential arterial hypertension and unspecified strokes clustered in the southern states of Mexico (Supplementary Figure S2, available as Supplementary data at IJE online). We also evaluated age-adjusted excess mortality at the municipal level to obtain a more detailed overview of these geographical differences. Excess mortality had a heterogenous geographical distribution and correlated with the SLI in municipalities in Mexico with higher excess mortality due to both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 causes (Supplementary Figure S3, available as Supplementary data at IJE online). At the state level, the highest decrease in non-COVID-19 in-hospital deaths was seen in Oaxaca, Yucatan and Veracruz, whereas the highest proportion of non-COVID-19 out-of-hospital deaths were observed in Tlaxcala, Yucatan and Colima (Supplementary Figure S4, available as Supplementary data at IJE online).

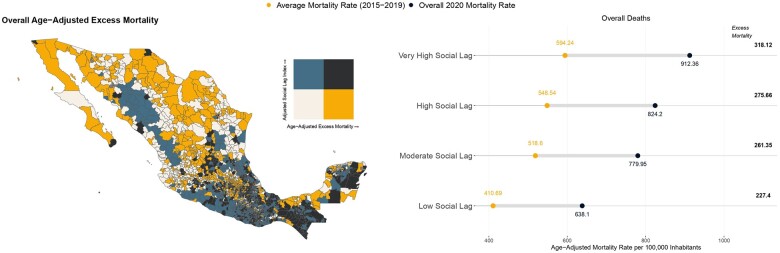

Municipal-level impact of socio-demographic inequalities in excess mortality

We observed marked geographic variability in age-adjusted excess mortality across municipalities with higher aSLI (Figure 3a). After excluding COVID-19-related deaths, only the southern municipalities displayed the highest combination of excess mortality and aSLI (Supplementary Figure 5, available as Supplementary data at IJE online). Stratifying by aSLI categories, age-adjusted mortality rates and excess mortality showed a stepwise increase with each higher marginalization level (Figure 3b). Municipalities with very high aSLI displayed both the higher age-adjusted mortality (912.36 per 100 000 inhabitants) and excess mortality (318.12 per 100 000 inhabitants) rates in Mexico.

Figure 3.

Geographical distribution and age-adjusted excess mortality by adjusted social lag categories in Mexico in 2020. (a) Choropleth map of Mexico to visualize the geographical distribution of age-adjusted excess mortality and adjusted social lag index by municipality of occurrence in 2020. (b) Age-adjusted average mortality rate (2015–2019), overall mortality rate in 2020 and excess mortality stratified by adjusted social lag categories in Mexico

Municipal-level correlates of excess mortality

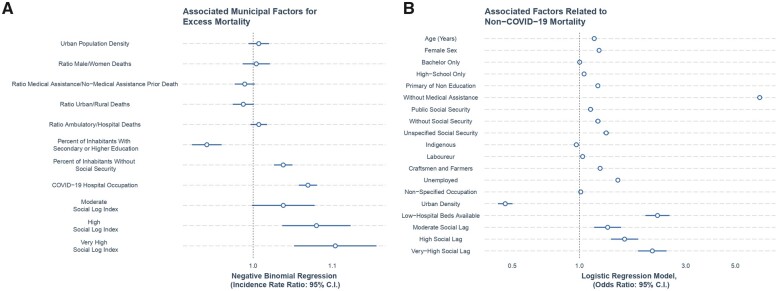

To evaluate the hypothesis that excess mortality was correlated with social inequalities in healthcare access and hospital occupancy due to COVID-19 at the municipal level, we fitted negative binomial regression models for age-adjusted excess mortality rates. As observed in the geographic distribution of age-adjusted excess mortality (Supplementary Figure S5, available as Supplementary data at IJE online), municipalities at high and very high social lag had the highest risk for non-COVID-19 age-adjusted excess mortality in 2020. Municipalities with a higher percentage of the population without social security coverage (IRR 1.03, 95% CI 1.02–1.04), higher COVID-19 hospital occupancy (IRR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01–1.06) and higher social lag categories were at higher risk of excess mortality after adjusting for covariates (Figure 4). We observed an interaction effect for higher risk of non-COVID-19 age-adjusted excess mortality in municipalities with very high social lag and higher COVID-19 hospital occupancy (IRR 1.08, 95% CI 1.03–1.12, Supplementary Figure S6, available as Supplementary data at IJE online).

Figure 4.

Regression models to evaluate factors for excess mortality and death from non-COVID-19 causes. (a) Negative binomial regression model to evaluate municipal-level factors related to excess mortality. (b) Logistic regression model to assess individual-related factors linked to the probability of death from non-COVID-19 causes

Individual-factor correlates of non-COVID-19 deaths

Finally, we explored the role of socio-demographic conditions and healthcare-related inequalities for the risk of non-COVID-19 deaths using random-effects logistic regression models. We observed that women, people who had lower educational attainment and those who worked as craftsmen, farmers, labourers or were unemployed had an increased odds for death attributable to non-COVID-19 compared with COVID-19 causes. Regarding healthcare-related factors, people without medical assistance before death, people who reported public or unspecified social security coverage or people who lived in municipalities with low availability of hospital beds had an increased odds of death from non-COVID-19 compared with COVID-19 causes. Finally, people living in municipalities with high and very high social lag had the highest odds of non-COVID-19 compared with COVID-19 death (Figure 4).

Discussion

In this study of 1 069 174 deaths recorded in Mexico between 2015 and 2020, we report that 51% of deaths in 2020 were in excess compared with the average reported between 2015 and 2019. Although cause-specific excess mortality during 2020 was largely attributable to COVID-19 (76.1% of cases), non-COVID-19 causes comprised up to one-fifth of excess deaths in Mexico during 2020. Moreover, we report a differential impact on excess mortality related to the setting in which the deaths occurred; whereas COVID-19 deaths occurred primarily in-hospital, non-COVID-19 deaths sharply decreased in this setting and had a concurrent increase in the out-of-hospital setting. These findings contribute to the growing literature on the far-reaching impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health system and suggest both an excess in non-COVID-19 mortality as well as a displacement of these deaths to the out-of-hospital setting in Mexico.

We also observed that excess mortality exhibited marked geographical heterogeneity, which was associated with higher social lag; states in the southern region of Mexico had the highest social marginalization and similarly high rates of non-COVID-19 excess mortality. We showed that lower prevalence of population without social security coverage and higher rates of COVID-19 hospitalization, combined with social marginalization, were municipal-level correlates of non-COVID-19 excess mortality. Finally, at the individual level, lower educational attainment, blue-collar employment (labourers, craftsmen and farmers), unemployment and lack of medical assistance before death were significant correlates of non-COVID-19 compared with COVID-19 mortality during 2020. These findings suggest that excess mortality from non-COVID-19-related causes, which occurred disproportionately out-of-hospital and among populations with social disadvantage, may reflect a complex interplay between a fragmented health system, strained hospital capacity, interruptions in chronic disease care and socio-demographic inequalities further unmasked by the pandemic.5 This situation is applicable to Mexico, but also to countries with similar socio-demographic profiles in the region or with high rates of SARS-CoV-2 infections.

Previous reports have documented the high burden of excess mortality caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico, with excess mortality rates being estimated from 26.1 to 36.0 deaths per 100 000 inhabitants;6,13,17–19 moreover, Karlinsky et al. projected that Mexico’s actual toll of deaths could be twice the number of deaths registered during 2020.14 These reports positioned Mexico as one of the leading countries in terms of excess mortality in Latin America and worldwide.6,13 However, there is limited information regarding cause-specific contributors to global excess mortality rates in Mexico. Besides contributing to the literature on COVID-19 excess mortality in Mexico, our findings also expand this literature by showing that excess deaths were also related to cardiometabolic chronic health conditions, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, arterial hypertension and obesity, which had a steep increase in the out-of-hospital setting.9,20 Excess non-COVID-19 deaths could be attributable to hospital reconversion policies and healthcare restructuration designed to improve care for COVID-19 cases, which may have reduced access to care for people with chronic health conditions who required continuous medical assistance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Other high-income countries have documented the association between hospital occupancy and excess mortality during periods of peak COVID-19 infections.21–23 Explanations related to this phenomenon rely on data on restricted access to healthcare services in places that experienced hospital overload due to COVID-19, reduced out-of-hospital attention due to severely restricted healthcare services and personnel availability, lower insurance coverage and a lower number of healthcare personnel per capita.24–26 Other reported non-related healthcare contributors were social stigma for being treated in hospitals due to potentially acquiring COVID-19 infection and reduced physical activity due to pandemic restrictions on mobility, which could have exacerbated complications due to chronic health conditions.27 Overall, excess non-COVID-19 mortality could be interpreted as an indirect proxy of the negative effects attributable to healthcare policies that prioritized in-hospital COVID-19 attention over the care of other chronic health conditions.

Notably, increased rates of COVID-19 hospitalizations and mortality in Mexico were observed in municipalities with high marginalization independently of urbanization, likely attributed to increased stress on their healthcare systems.28,29 This phenomenon may explain the disproportionate burden of non-COVID-19 deaths among marginalized municipalities in Mexico. Our results support the hypothesis that populations with social disadvantage experienced the highest impact of excess mortality attributable to hospital saturation, with this impact having an unequal distribution within Mexico. In the European region, countries with high excess mortality, such as Bulgaria, Russia and Serbia, were impacted by diverse social barriers, such as difficulties in fully adhering to social isolation policies.30,31 Two recent reports in England showed that communities with a high density of care homes, with a high proportion of residents on income support, overcrowding conditions and ethnic minorities were at higher risk of excess mortality and years of life lost due to the COVID-19 pandemic.32,33 In Latin American countries, socio-economic inequalities widened due to difficulty adhering to lockdown mandates given low stipend support, a high proportion of their population working in the informal economy and lack of access to healthcare, even among healthcare personnel.3,30,34 Nevertheless, this evidence and the comparison between countries should be interpreted with caution given the variation in COVID-19 dynamics, within-country gradients of socio-demographic inequalities and different epidemiological profiles of high-risk co-morbidities.

Our results highlight the impact of healthcare-related and individual-level social inequalities in exacerbating overall and cause-specific excess mortality in Mexico. We show that the main contributor to higher non-COVID-19 excess mortality rates at the municipal level was a lower percentage of the population with access to social security health coverage; in Mexico, social security providers condition the type of healthcare access by individuals, which likely also influences received quality of care and healthcare access. Furthermore, the interaction between a lower percentage of the population with access to social security health coverage and social marginalization confirmed the hazardous interplay between social and healthcare inequalities.35 At the individual level, we showed that certain socially vulnerable occupations experienced unequal risks for non-COVID-19 mortality. The role of individual and socio-demographic determinants in the risk for adverse COVID-19 outcomes has been previously reported.36,37 Nevertheless, our findings demonstrate that socio-demographic inequalities impacted individuals with preventable chronic conditions, regardless of public healthcare policies aimed at mitigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in healthcare infrastructure and provision. Overall, our results represent an urgent call to action for local authorities to perform a healthcare restructuration, particularly in marginalized municipalities and with special attention to vulnerable populations to prioritize full coverage of hospital bed capacity, well-trained healthcare personnel and availability of primary care services that cover the management of chronic health conditions. These policies could prevent associated complications in the context of future COVID-19 waves or other circumstances that increase stress and reduce access to healthcare in Mexico and other LMICs.

Our study has some strengths and limitations. Among the strengths, we highlight the use of 1 069 174 nationwide mortality registries to compare all-cause and cause-specific excess mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico in 2020. This approach allowed us to estimate with higher confidence state- and municipal-level excess mortality rates that helped us to study the regional impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and identify vulnerable zones in Mexico that were especially affected during 2020 compared with previous years. Additionally, the use of socio-demographic variables at different levels gave us insights to evaluate municipal- and individual-level correlates of excess non-COVID-19 mortality. Nevertheless, limitations to be acknowledged include the lack of specific clinical information and co-morbidity assessment for correlates known to be key determinants of higher risk of death from COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 causes, particularly regarding management of chronic cardiometabolic conditions. Second, we could not ascertain the number of non-COVID-19 deaths that occurred due to exacerbation of underlying chronic conditions by current or previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, which could increase the risk of long-term complications, including cardiovascular diseases.3 Third, our COVID-19 death construct included cases that could have been misclassified as atypical pneumonia or severe acute respiratory infections of unknown aetiology, registered after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic; this was done to reduce the risk of under-reporting or misclassified COVID-19 deaths, but could have led to overestimation of COVID-19 deaths. Fourth, we used a surveillance data set to assess COVID-19 hospitalization as a proxy for hospital occupancy; however, identification of COVID-19-related hospitalizations may have varied according to weekly SARS-CoV-2 testing capacity and adequate reporting. Therefore, the use of this proxy could be biased in municipalities with higher marginalization and reduced access to testing. Finally, our municipal-level factors should be interpreted as structural conditions that displayed an association with higher excess mortality rates and therefore we should avoid an ecological fallacy in determining personal actions in clinical and healthcare management during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In conclusion, we show a high burden of excess mortality in Mexico in 2020, largely attributable to in-hospital COVID-19 and out-of-hospital non-COVID-19 deaths. We observed regional heterogeneity of non-COVID-19 excess mortality, with a disproportionate burden on marginalized municipalities in southern Mexico. High hospital occupancy due to COVID-19 and a higher percentage of the population without social security coverage were municipal-wide-level correlates of excess mortality, whereas individual-level lower educational attainment, vulnerable working occupations, lack of medical assistance before death and public or underspecified healthcare access were factors related to higher non-COVID-19 mortality likelihood. Our findings underscore the impact of socio-demographic inequalities on excess mortality related to non-COVID-19 causes in Mexico during 2020 compared with the 2015–2019 period. These results should prompt an urgent call to action to improve healthcare coverage and access, particularly in primary care settings and among populations with social disadvantage. Such policies could reduce health disparities in Mexico in circumstances that increase the stress of healthcare systems, including the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

Ethics approval

This project was registered and approved by the Ethics and Research Committee at Instituto Nacional de Geriatría, project number DI-PI-006/2020.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

N.E.A.V. and C.A.F.M. are enrolled at the PECEM program of the Faculty of Medicine at UNAM. N.E.A.V. is supported by CONACyT. The authors would like to acknowledge the invaluable work of all of Mexico’s healthcare community in managing the COVID-19 pandemic. Their participation in the COVID-19 surveillance programme along with open data sharing has made this work a reality; we are thankful for your effort.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Contributor Information

Neftali Eduardo Antonio-Villa, Division de Investigación, Instituto Nacional de Geriatría, Mexico City, Mexico; MD/PhD (PECEM) Program, Faculty of Medicine, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City, Mexico.

Omar Yaxmehen Bello-Chavolla, Division de Investigación, Instituto Nacional de Geriatría, Mexico City, Mexico.

Carlos A Fermín-Martínez, Division de Investigación, Instituto Nacional de Geriatría, Mexico City, Mexico; MD/PhD (PECEM) Program, Faculty of Medicine, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City, Mexico.

José Manuel Aburto, Leverhulme Centre for Demographic Science, Department of Sociology, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kindom; Interdisciplinary Centre on Population Dynamics, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark.

Luisa Fernández-Chirino, Division de Investigación, Instituto Nacional de Geriatría, Mexico City, Mexico; Faculty of Chemistry, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City, Mexico.

Daniel Ramírez-García, Division de Investigación, Instituto Nacional de Geriatría, Mexico City, Mexico.

Julio Pisanty-Alatorre, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, Mexico City, Mexico; Departamento de Salud Pública, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico.

Armando González-Díaz, Facultad de Ciencias Politicas Sociales y Sociales, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City, Mexico.

Arsenio Vargas-Vázquez, Division de Investigación, Instituto Nacional de Geriatría, Mexico City, Mexico; MD/PhD (PECEM) Program, Faculty of Medicine, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico City, Mexico.

Simón Barquera, Health and Nutrition Research Center, National Institute of Public Health, Cuernavaca, Mexico.

Luis Miguel Gutiérrez-Robledo, Division de Investigación, Instituto Nacional de Geriatría, Mexico City, Mexico.

Jacqueline A Seiglie, Diabetes Unit, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America; Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America.

Data Availability

All code, data sets and materials are available for reproducibility of results at https://github.com/oyaxbell/excess_non_covid/.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at IJE online.

Author contributions

Research idea and study design: N.E.A.V., C.A.F.M., O.Y.B.C.; data acquisition: N.E.A.V., C.A.F.M.; data analysis/interpretation: N.E.A.V., C.A.F.M., J.M.A., L.F.C., J.P.A., A.G.D., A.V.V.; statistical analysis: N.E.A.V., C.A.F.M., O.Y.B.C.; manuscript drafting: N.E.A.V., O.Y.B.C., C.A.F.M., J.M.A., L.F.C., J.P.A., A.G.D., A.V.V., J.A.S., S.B., L.M.G.R.; supervision or mentorship: N.E.A.V., O.Y.B.C. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepted accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

This research was supported by Instituto Nacional de Geriatría.

References

- 1. Wang H, Paulson KR, Pease SA. et al. Estimating excess mortality due to the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic analysis of COVID-19-related mortality, 2020-21. Lancet 2022;399:1513–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Doubova SV, Leslie HH, Kruk ME, Pérez-Cuevas R, Arsenault C.. Disruption in essential health services in Mexico during COVID-19: an interrupted time series analysis of health information system data. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e006204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arceo-Gomez EO, Campos-Vazquez RM, Esquivel G, Alcaraz E, Martinez LA, Lopez NG.. The income gradient in COVID-19 mortality and hospitalisation: an observational study with social security administrative records in Mexico. Lancet Reg Health Am 2022;6:100115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Islam N. ‘Excess deaths’ is the best metric for tracking the pandemic. BMJ 2022;376:o285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Doubova SV, García-Saiso S, Pérez-Cuevas R. et al. Quality governance in a pluralistic health system: Mexican experience and challenges. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e1149–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lima EEC, Vilela EA, Peralta A. et al. Investigating regional excess mortality during 2020 COVID-19 pandemic in selected Latin American countries. Genus 2021;77:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bello-Chavolla OY, Bahena-López JP, Antonio-Villa NE. et al. Predicting mortality due to SARS-CoV-2: a mechanistic score relating obesity and diabetes to COVID-19 outcomes in Mexico. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020;105: 2752–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gutiérrez JP, García-Saisó S.. Health inequalities: Mexico’s greatest challenge. Lancet 2016;388:2330–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Palacio-Mejía LS, Hernández-Ávila JE, Hernández-Ávila M. et al. Leading causes of excess mortality in Mexico during the COVID-19 pandemic 2020-2021: a death certificates study in a middle-income country. Lancet Reg Health Am 2022;13:100303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Datos de Mortalidad en México. 2021. https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/mortalidad/#Documentacion (4 September 2022, date last accessed).

- 11. Kontopantelis E, Mamas MA, Webb RT. et al. Excess deaths from COVID-19 and other causes by region, neighbourhood deprivation level and place of death during the first 30 weeks of the pandemic in England and Wales: a retrospective registry study. Lancet Reg Health—Eur 2021;7:100144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dirección General de Información en Salud. Catálogos de Defunciones. 2021. http://www.dgis.salud.gob.mx/contenidos/basesdedatos/da_defunciones_gobmx.html (4 September 2022, date last accessed).

- 13. Karlinsky A, Kobak D.. Tracking excess mortality across countries during the COVID-19 pandemic with the World Mortality Dataset. eLife 2021;10:e69336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. CONEVAL. Índice Rezago Social. 2015. https://www.coneval.org.mx/Medicion/IRS/Paginas/Indice_Rezago_Social_2015.aspx (4 September 2022, date last accessed).

- 15. Direccion General de Epidemiología. COVID-19-MEXICO. 2020. https://datos.covid-19.conacyt.mx (4 September 2022, date last accessed).

- 16. INEGI. Metodología de Indicadores de la Serie Histórica Censal. 2018. https://inegi.org.mx/contenidos/programas/ccpv/cpvsh/doc/serie_historica_censal_met_indicadores.pdf (4 September 2022, date last accessed).

- 17. Palacio-Mejía LS, Wheatley-Fernández JL, Ordóñez-Hernández. All-cause excess mortality during the Covid-19 pandemic in Mexico. Salud Publica Mex 2021;63:211–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dahal S, Banda JM, Bento AI, Mizumoto K, Chowell G.. Characterizing all-cause excess mortality patterns during COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico. BMC Infect Dis 2021;21:432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dahal S, Luo R, Swahn MH, Chowell G.. Geospatial variability in excess death rates during the COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico: examining socio demographic, climate and population health characteristics. Int J Infect Dis 2021;113:347–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bello-Chavolla OY, Antonio-Villa NE, Fermín-Martínez CA, et al Diabetes-related excess mortality in Mexico: a comparative analysis of national death registries between 2017–2019 and 2020. medRxiv; doi: 10.1101/2022.02.24.22271337, 25 February 2022, preprint: not peer reviewed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21. French G, Hulse M, Nguyen D. et al. Impact of hospital strain on excess deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic: United States, July 2020-July 2021. Am J Transplant Off Transplant 2022;22:654–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Michelozzi P, de'Donato F, Scortichini M. et al. Temporal dynamics in total excess mortality and COVID-19 deaths in Italian cities. BMC Public Health 2020;20:1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rossman H, Meir T, Somer J. et al. Hospital load and increased COVID-19 related mortality in Israel. Nat Commun 2021;12:1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pilkington H, Feuillet T, Rican S. et al. Spatial determinants of excess all-cause mortality during the first wave of the COVID-19 epidemic in France. BMC Public Health 2021;21:2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stokes AC, Lundberg DJ, Bor J, Elo IT, Hempstead K, Preston SH.. Association of health care factors with excess deaths not assigned to COVID-19 in the US. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2125287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Watkins DA. Cardiovascular health and COVID-19: time to reinvent our systems and rethink our research priorities. Heart 2020;106:1870–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bagcchi S. Stigma during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20:782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Naja F, Hamadeh R.. Nutrition amid the COVID-19 pandemic: a multi-level framework for action. Eur J Clin Nutr 2020;74:1117–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang J. Hospital avoidance and unintended deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Health Econ 2021;7:405–26. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kapitsinis N. The underlying factors of excess mortality in 2020: a cross-country analysis of pre-pandemic healthcare conditions and strategies to cope with COVID-19. BMC Health Serv Res 2021;21:1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gallo V, Mackenbach JP, Ezzati M. et al. Social inequalities and mortality in Europe: results from a large multi-national cohort. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e39013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Davies B, Parkes BL, Bennett J. et al. Community factors and excess mortality in first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in England. Nat Commun 2021;12:3755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kontopantelis E, Mamas MA, Webb RT. et al. Excess years of life lost to COVID-19 and other causes of death by sex, neighbourhood deprivation, and region in England and Wales during 2020: a registry-based study. PLoS Med 2022;19:e1003904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Antonio-Villa NE, Bello-Chavolla OY, Vargas-Vázquez A. et al. Assessing the Burden of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) among healthcare workers in Mexico City: a data-driven call to action. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am 2021;73:e191–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ji Y, Ma Z, Peppelenbosch MP, Pan Q.. Potential association between COVID-19 mortality and health-care resource availability. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:e480. Vol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fielding-Miller RK, Sundaram ME, Brouwer K, Social determinants of COVID-19 mortality at the county level. medRxiv; doi: 10.1101/2020.05.03.20089698, 1 July 2020, preprint: not peer reviewed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37. Antonio-Villa NE, Fernandez-Chirino L, Pisanty-Alatorre J. et al. Comprehensive evaluation of the impact of sociodemographic inequalities on adverse outcomes and excess mortality during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Mexico City. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am 2022;74:785–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All code, data sets and materials are available for reproducibility of results at https://github.com/oyaxbell/excess_non_covid/.