Abstract

Background

COVID-19 is a major public health problem. In mid-2020, due to the health system challenges from increased COVID-19 cases, the Ministry of Health and Social Action in Senegal opted for contact management and care of simple cases at home. The objective of the study was to determine the acceptability of contact and simple case management of COVID-19 at home and its associated factors in Senegal.

Methods

This was a descriptive and analytical cross-sectional study. We collected data from 11 June to 10 July 2020. We used a marginal quota sampling strategy. A total of 813 individuals took part in the survey. We collected data using a telephone interview.

Results

The care of simple cases of COVID-19 at home was well accepted (78.5%). The use of home contact management was less accepted (51.4%). Knowledge of the modes of transmission of the virus and confidence in institutional information were associated with the acceptability of home care for simple cases. Regularly searching for information on COVID-19 and confidence in the government's control of the epidemic were associated with the acceptability of managing contacts at home.

Conclusions

Authorities should take these factors into account for better communication to improve the acceptability and confidence in home-based care for COVID-19 and future epidemics.

Keywords: case management, COVID-19, home care services, Senegal, telephone

Introduction

COVID-19 is now a major public health problem. To interrupt the chains of transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the causative agent of COVID-19, non-pharmaceutical measures such as case detection, case management in dedicated centres1 and screening and quarantine of contacts have been proposed.2 These measures aim to prevent the further transmission of secondary infections. They have been used successfully to prevent further outbreaks in South Korea.2

In Senegal, as soon as the first case of COVID-19 appeared on 2 March 2020, the authorities put a national multisectoral action plan into place for monitoring and response.3 The government accompanied this plan with measures such as border closures, curfews, bans on movement between regions, closure of places of worship and closure of markets.4,5 They established epidemiological treatment centres (ETCs) in all regions to manage COVID-19 cases. On 22 March 2020 they began to isolate contacts in hotel facilities.5

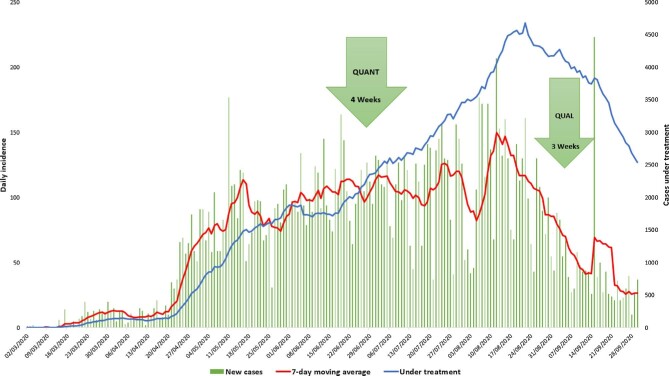

Despite the unprecedented national measures taken, COVID-19 cases continued to increase (Figure 1),6,7 leading to an increase in the number of contacts requiring follow-up.

Figure 1.

Epidemic curve of COVID-19 confirmed cases (https://www.covid19afrique.com).

Faced with this increase and the saturation of the health system and hotels to take care of patients and contacts, respectively, on 15 May 2020, the authorities decided to stop monitoring contacts in hotels and care of simple cases in the ETCs. For the care of simple cases of COVID-19, they first adopted an extra-hospital care policy (dedicated sites outside the ETCs like hotels) at the end of April 20208 then a home care policy in July 2020 with protocol to be respected.9 A simple case is defined as a patient confirmed as COVID-19 who presents signs of uncomplicated upper respiratory tract infection such as fatigue, cough (with or without phlegm), nausea or vomiting, muscle pain, sore throat, nasal congestion, headache, ageusia (loss of taste) and anosmia (loss of smell).9 A contact is defined as a person (including caregivers and health workers) who has been exposed to individuals with suspected COVID-19 disease; they are advised to monitor their health for 14 d from the last day of contact.10

The recent SARS and Ebola epidemics used home-based management approaches.11 However, there are some risks associated with this strategy, including the spread of the virus within households and, in the community,1 social stigma,12 which undermines these measures’ potential effectiveness. Several countries and the WHO have developed guidelines for the home management of COVID cases.10,13–15 Indeed, the vast majority of patients infected with COVID-19 develop a benign disease.16 A few studies have shown that the ideal way to control the COVID-19 pandemic is to isolate patients in health facilities with appropriate respiratory precautions, contact tracing and barrier measures.17–19 However, isolation in health facilities would result in a shortage of beds for other patients.15 In this context, home-based management (a familiar environment with family support) is necessary and could help to overcome psychological problems.20 However, to our knowledge, these guidelines and studies on the subject have not addressed the social acceptability of these measures. Thus, our objective was to determine the acceptability of contact and simple case management of COVID-19 at home and its associated factors in Senegal.

Methods

Study setting

The study took place in the 14 regions of Senegal. The average age in Senegal is 19 y and males make up 49.7% of the population.21 The number of confirmed COVID-19 cases on the day the survey started (11 June 2020) was 4759 (of which 1709 were under treatment)7 with 76.5% of cases in the Dakar region. The organisation of the socio-sanitary sector is pyramidal (central, intermediate and peripheral levels), based on administrative divisions.22 There are 20 ETCs in all regions of Senegal.23 They have a capacity of 800 inpatient beds24 and 80 beds for resuscitation and respirators were available in May throughout the country.25 In Senegal, the mobile penetration rate is >110%, with users often having two or even three different SIM cards with several operators.26

Research estimates, period and study population

This was a descriptive and analytical cross-sectional study.27 We collected data from 11 June to 10 July 2020. The study population consisted of people aged ≥18 y in the general population with a mobile phone number.

Sampling

The quantitative study used a marginal quota sampling strategy.28 This method is relevant in emergency situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic with sample sizes of <3000.28,29 To have a representative sample of the population, we carried out stratification by population weight by region, gender and age group. We randomly generated a nine-digit telephone number list from mobile telephone numbers attributable to Senegal using the random digit dialling method. We integrated this list into a reactive auto dialler to trigger calls automatically and optimally. A total of 813 individuals took part in the quantitative survey. The procedure for arriving at the final sample has been described in another article.30

Data collection

Five interviewers speaking six languages (French, Diola, Wolof, Sérére, Pulaar and Soninké) collected the quantitative data using a structured and closed questionnaire. The interviewers conducted the survey by telephone. They used tablets equipped with Open Data Kit software (Get ODK, San Diego, California, USA) to administer the questionnaire.31,32

The final version of the questionnaire was first tested during the training of the interviewers then was validated by the team members after several corrections.

We conceptualised the collected variables in accordance with Bruchon-Schweitzer's integrative and multifactorial model.33 This model has good content validity for this study as it integrates most of the variables identified in the literature review. According to the model, we divided the factors in our study into three groups: situational, dispositional and transactional.

Situational factors are sociodemographic characteristics such as age, gender, region, education level, marital status and economic well-being score. Dispositional factors are knowledge about the cause of the disease, symptoms, modes of transmission and availability of treatment and other variables such as trust in government, information seeking and trust in different information sources (institutions, national media, social networks, health professionals and other applications). Transactional factors are concerns about the epidemic and psychosocial well-being.34 The independent variables are defined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definition of independent variables

| Variables | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Regularly search for information on COVID-19 | Yes=Yes, absolutely; Yes, rather Yes=Yes, absolutely; Yes, rather |

| No/NSP=No, not at all; No, rather not; I don't know | |

| Confidence in information sources | Yes=Yes, absolutely; Yes, rather |

| No/NSP=No, not at all; No, rather not; I don't know | |

| Knowledge about the cause of COVID-19 | Good=virus |

| Wrong=Other answers | |

| Knowledge about the signs of the disease | Good=When the respondent had cited 3 signs of the disease |

| Bad=When the respondent had cited <3 signs of the disease | |

| Knowledge of the modes of transmission of the virus | Good=When the respondent had cited ≥2 modes of transmission of the virus |

| Bad=When the respondent had cited <2 modes of transmission of the virus | |

| Belief in the existence of treatment | Yes=Yes, absolutely; Yes, rather |

| No/NSP=No, not at all; No, rather not; I don't know | |

| Psychosocial well-being | The WHO's 5-item index of well-being is a subjective measure of the positive dimensions of mental health. The 5 items ask about how people felt in the last 2 wk and included: ‘I felt good and in good spirits’, ‘I felt calm and quiet’, ‘I felt energetic and vigorous’, ‘I woke up feeling fresh and refreshed’ and ‘My daily life was full of interesting things’. Six response modalities: all the time rated 5, most of the time 4, more than half of the time 3, less than half of the time 2, occasionally 1 and never 0. An overall score is obtained by adding up the responses to the 5 items and ranges from 0 to 25. Well-being was considered good when the respondent had a score of ≥13. |

| Acceptability of the 4 government measures | To deal with the pandemic, the Senegalese government had taken measures against the population, including curfews, travel bans and the closure of markets and places of worship. Each of these measures was measured by 7 items, which gave us a score ranging from 0 to 7. A measure was considered to be respected when the respondent had a score of ≥6. Compliance with a measure was coded as 1 and non-compliance as 0. A respondent was considered to accept all 4 measures when they scored 1 in all 4 measures. |

We measured the acceptability (the dependent variable) using a five-point Likert scale (strongly agree=5 to not at all agree=1). It was transformed into binary variables (Yes=Strongly agree and Agree) to determine acceptability levels and identify associated factors.

Data analysis

The quantitative analyses were carried out using R software version 4.0.2. The quantitative variables are described through the mean with its SD and the qualitative variables through the frequencies. We used the Student's test to compare mean ages, and the χ2 test to compare other characteristics with a 5% alpha risk. We used binomial logistic regression in the multivariate analysis. We ran two models to determine the factors associated with the acceptability of management of home contacts (model 1) and those associated with care of simple home cases (model 2). We included all variables with p<0.25 in the original models.35 We used the step-by-step top-down selection procedure in each model to construct the final model. We individually removed variables that did not improve the model. We used the likelihood ratio test to compare nested models.36 We used this multivariate analysis to determine adjusted ORs (ORajs).

Results

The average age of the respondents was 34.70±14.20 y. Males represented 54.6%. In our study, the proportion of individuals who lived in the capital was 30.4%. The proportion of people who had no education was 42.6%. Those with secondary/university education was 38.5%. Married people were in the majority with a proportion of 30.4% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Participants’ characteristics (N=813)

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 369 (45.4%) |

| Male | 444 (54.6%) |

| Region | |

| Dakar | 247 (30.4%) |

| Outside Dakar | 566 (69.6%) |

| Level of education | |

| Uneducated | 346 (42.6%) |

| Primary | 154 (18.9%) |

| Secondary/higher | 313 (38.5%) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 499 (61.4%) |

| Unmarried | 314 (38.6%) |

| Economic well-being score | |

| Poor | 229 (28.2%) |

| Medium | 165 (20.3%) |

| Rich | 419 (51.5%) |

The proportion of participants who accepted care for simple COVID-19 cases at home was 78.5%. Furthermore, 48.6% of the participants did not accept the management of COVID-19 contacts at home.

The proportion of acceptability of management for home contacts among participants with a good knowledge of the modes of transmission of the virus was 56.1%, while for those with poor knowledge it was 39.0% (p<0.001). The proportion of acceptability of care of simple cases at home among participants who believed that treatment was available was 85.5%, while that of others was 74.8% (p=0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Breakdown of respondents by characteristics and acceptability of home-based care (N=813)

| Variable | N (% acceptability of management of home contacts) | p | N (% acceptability of care for simple cases at home) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (µ±σ) | 35.5 (14.2) | 0.097 | 34.6 (14.1) | 0.653 |

| Gender | 0.754 | 0.854 | ||

| Female | 369 (50.7%) | 369 (78.0%) | ||

| Male | 444 (52.0%) | 444 (78.8%) | ||

| Level of education | 0.594 | 0.056 | ||

| Uneducated | 346 (50.0%) | 346 (74.6%) | ||

| Primary | 154 (50.0%) | 154 (79.9%) | ||

| Secondary/higher | 313 (53.7%) | 313 (82.1%) | ||

| Region | 0.492 | 0.155 | ||

| Outside Dakar | 566 (50.5%) | 566 (77.0%) | ||

| Dakar | 247 (53.4%) | 247 (81.8%) | ||

| Marital status | 1.000 | 0.588 | ||

| Unmarried | 314 (51.3%) | 314 (79.6%) | ||

| Married | 499 (51.5%) | 499 (77.8%) | ||

| Economic well-being score | 0.570 | 0.035 | ||

| Poor | 229 (53.7%) | 229 (83.8%) | ||

| Medium | 165 (52.7%) | 165 (79.4%) | ||

| Rich | 419 (49.6%) | 419 (75.2%) | ||

| Confidence in the government to fight the epidemic | 0.081 | 0.309 | ||

| No | 524 (49.0%) | 524 (77.3%) | ||

| Yes | 289 (55.7%) | 289 (80.6%) | ||

| Regular search for information on COVID-19 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| No/NSP | 290 (35.2%) | 290 (66.2%) | ||

| Yes | 523 (60.4%) | 523 (85.3%) | ||

| Confidence in institutional information | 0.004 | <0.001 | ||

| No/NSP | 352 (45.5%) | 352 (69.6%) | ||

| Yes | 461 (56.0%) | 461 (85.2%) | ||

| Confidence in national media information | 0.355 | 0.088 | ||

| No/NSP | 135 (47.4%) | 135 (72.6%) | ||

| Yes | 678 (52.2%) | 678 (79.6%) | ||

| Confidence in information from social networks | <0.001 | 0.148 | ||

| No/NSP | 634 (47.8%) | 634 (77.3%) | ||

| Yes | 179 (64.2%) | 179 (82.7%) | ||

| Confidence in information from health professionals | 0.636 | 0.410 | ||

| No/NSP | 56 (55.4%) | 56 (73.2%) | ||

| Yes | 757 (51.1%) | 757 (78.9%) | ||

| Confidence in information from WhatsApp or other application | 0.001 | 0.289 | ||

| No/NSP | 653 (48.5%) | 653 (77.6%) | ||

| Yes | 160 (63.1%) | 160 (81.9%) | ||

| Knowledge about the cause of COVID-19 | 0.826 | 0.869 | ||

| Wrong | 593 (51.1%) | 593 (78.2%) | ||

| Good | 220 (52.3%) | 220 (79.1%) | ||

| Knowledge about the signs of the disease | 0.034 | 0.935 | ||

| Wrong | 595 (49.1%) | 595 (78.3%) | ||

| Good | 218 (57.8%) | 218 (78.9%) | ||

| Knowledge of the modes of transmission of the virus | <0.001 | 0.002 | ||

| Wrong | 223 (39.0%) | 223 (70.9%) | ||

| Good | 590 (56.1%) | 590 (81.4%) | ||

| Belief in the existence of treatment | 0.065 | 0.001 | ||

| No/NSP | 531 (49.0%) | 531 (74.8%) | ||

| Yes | 282 (56.0%) | 282 (85.5%) | ||

| Concern about the epidemic | 0.022 | 0.651 | ||

| No | 442 (55.2%) | 442 (79.2%) | ||

| Yes | 371 (46.9%) | 371 (77.6%) | ||

| Psychosocial well-being | 0.156 | 0.605 | ||

| Wrong | 41 (63.4%) | 41 (82.9%) | ||

| Good | 772 (50.8%) | 772 (78.2%) |

Abbreviation: NSP, Don't know.

Table 4 shows that the acceptability of management for home-based contacts could be based on trust in the government to fight the epidemic (ORaj: 1.51 [95% CI 1.10 to 2.08]), knowledge about the modes of transmission of the virus (ORaj: 1.77 [95% CI 1.27 to 2.48]), concern about the epidemic (ORaj: 0.68 [95% CI 0.50 to 0.93]) and regularly searching for information on COVID-19 (ORaj: 2.39 [95% CI 1.76 to 3.26]).

Table 4.

Results of multivariate analysis

| Acceptability of management for home contacts (Yes) | Acceptability of care for simple home cases (Yes) | |

|---|---|---|

| Feature | ORaj [95% CI] | ORaj [95% CI] |

| Age | 1.01 [0.99 to 1.02] | 0.99 [0.98 to 1.01] |

| Confidence in the government to fight the epidemic | ||

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.51 [1.10 to 2.08]* | 1.30 [0.87 to 1.94] |

| Knowledge about the cause of COVID-19 | ||

| Wrong | 1 | 1 |

| Good | 0.92 [0.66 to 1.28] | 0.94 [0.62 to 1.45] |

| Knowledge of the modes of transmission of the virus | ||

| Wrong | 1 | 1 |

| Good | 1.77 [1.27 to 2.48]* | 1.55 [1.04 to 2.28]* |

| Concern about the epidemic | ||

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 0.68 [0.50 to 0.93]* | 1.07 [0.73 to 1.57] |

| Regularly search for information on COVID-19 | ||

| No | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 2.39 [1.76 to 3.26]* | 2.12 [1.45 to 3.12]* |

| Confidence in information from social networks | ||

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 1.11 [0.69 to 1.85] | |

| Economic well-being score | ||

| Poor | 1 | |

| Medium | 0.69 [0.39 to 1.21] | |

| Rich | 0.46 [0.29 to 0.72]* | |

| Belief in the existence of treatment | ||

| No/NSP | 1 | |

| Yes | 1.82 [1.19 to 2.83]* | |

| Confidence in institutional information | ||

| No/NSP | 1 | |

| Yes | 2.10 [1.43 to 3.10]* |

Abbreviation: NSP, Don't know. Bold and *, statistically significant.

The acceptability of care of simple cases at home could be predicted by knowledge of the modes of transmission of the virus (ORaj: 1.55 [95% CI: 1.04 to 2.28]), regular research of information on COVID-19 (ORaj: 2.12 [95% CI 1.45 to 3.12]), wealth based on the score of economic well-being compared with poverty (ORaj: 0.46 [95% CI 0.29 to 0.72]), belief in the existence of treatment (ORaj: 1.82 [95% CI 1.19 to 2.83]) and trust in institutional information (ORaj: 2.10 [95% CI 1.43 to 3.10]).

Discussion

The current study found that while respondents supported care for simple cases of COVID-19 at home, they were more cautious about management for home contacts. These results are interesting given the adoption of this strategy by the Ministry of Health and Social Action (MoHSA).37 These results can be justified by the fact that the participants are concerned about health system overload, and accept their care at the community level. However, participants are more divided on the management of contacts. The WHO recommends isolation of contacts for 14 d after the last exposure to a confirmed case.2 During the Ebola epidemic, this isolation period was 21 d.38 A British survey revealed that only 10.9% of contacts adhere to quarantine and 18.2% adhere to self-isolation.39 Some of the factors preventing adherence to the isolation may be related to social and financial charges.40 The 14 d for COVID-19 are difficult to enforce as they take place in the home, and may expose the community to transmission of the virus if people do not isolate themselves. Thus, these results can be explained by the unknown status of these contacts, who may be asymptomatic then transmit the disease. The experience of the Ebola epidemic in Senegal had shown a negative perception of risk around contacts because people considered them infected with the virus.38 In addition to strengthening the monitoring of household contacts, efforts should be made to increase people's understanding of these measures through public health counselling, explaining the importance of management of household contacts to reduce transmission and strong local and social support networks to raise awareness.41

The study in Senegal found that individuals who trusted institutional sources were more likely to accept care of simple cases at home. Similarly, trust in government in the fight against the epidemic was positively associated with the acceptability of management for home-based contacts. This finding is similar to the study in Israel and China,42 which showed that trust in institutions represented a 'reservoir of favourable attitudes and good will' during the COVID-19 epidemic.43

Good knowledge of the modes of transmission of the virus was positively associated with the acceptability of contact management and care of simple cases at home. Since the beginning of the pandemic, the MoHSA has been explaining to the population about the importance of respecting collective and individual prevention measures.8 These prevention measures have been defined as necessary to curb the spread of the virus.44 Two studies conducted on HIV have shown that individuals with a good knowledge of the modes of transmission of the virus have a better knowledge of the modes of prevention.45,46 A study conducted in Senegal in April 2020 showed that barrier gestures seemed to be well followed.47 Compliance with these measures, together with knowledge of how the virus is transmitted, may explain the good acceptability of management among populations.

The regular search for information on COVID-19 was positively associated with the acceptability of contact management and care of simple cases at home. The information provides knowledge that the recipient did not possess or could not foresee.48 This definition recognises that information as an element of knowledge reduces ignorance about COVID-19. This knowledge will enable the community to consider the extent of the current context and to adhere to public health measures. A systematic review showed that the provision of information is an important factor in influencing public acceptability of the authorities' measures.49 This leads to a better understanding of the disease and autonomous decision-making in light of the evolution of the pandemic. This finding seems consistent because people know better what is good for them and are therefore reluctant to accept an intervention that interferes with their own decisions.49

Belief in the existence of treatment is positively associated with the acceptability of care in simple cases at home. To date, no specific medication has been recommended to prevent or treat infection of the new coronavirus.50 At the beginning of the epidemic, Senegal adopted a treatment protocol based on the treatment of patients with hydroxychloroquine51 or a combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin.52 This perception of the population in Senegal can be explained by national communication on the ‘encouraging’ results of this protocol,52 which has become a source of hope in the event of contamination, despite the risks involved in its acceptability.

Concern about the epidemic is negatively associated with the acceptability of management for home contacts. Health risks or threats, such as crises, involve emotional connotations and uncertainty about their health and economic implications.53 These risks lead to concern about the pandemic that may be due to the prospect of undesirable future consequences54 and may explain this attitude.

Limitations

Our study has certain limitations. It only involved people who had a mobile phone, thus excluding marginalised populations. In addition, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits our ability to draw conclusions about causality. However, the sample is representative of the Senegalese population.

Conclusion

This study shows that being regularly informed about the disease, knowing how it is transmitted and trusting institutions are important factors in the acceptance of COVID-19 management at the community level. It will be important for the authorities to consider and integrate these aspects for a more effective strategy. However, it is also necessary to have messages that are adapted and targeted according to the categories of the population.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the five interviewers who participated in the data collection: Tabaski Diouf, Coumba Sow, Fatoumata Dieme, Rokhaya Gueye and Mafoudya Camara. Also our technical partner, Cloudlyyours, who were able to put into place all the necessary tools for data collection. And also Heather Hickey, for proofreading and editing the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Mouhamadou Faly Ba, Institut de Santé et Développement, Université Cheikh Anta Diop, BP 16390, Fann-Dakar, Sénégal.

Valéry Ridde, Université Paris Cité, IRD, Ceped, F-75006 Paris, France.

Amadou Ibra Diallo, Institut de Santé et Développement, Université Cheikh Anta Diop, BP 16390, Fann-Dakar, Sénégal.

Jean Augustin Diégane Tine, Institut de Santé et Développement, Université Cheikh Anta Diop, BP 16390, Fann-Dakar, Sénégal.

Babacar Kane, Institut de Santé et Développement, Université Cheikh Anta Diop, BP 16390, Fann-Dakar, Sénégal.

Ibrahima Gaye, Institut de Santé et Développement, Université Cheikh Anta Diop, BP 16390, Fann-Dakar, Sénégal.

Zoumana Traoré, CloudlyYours, 6 Rue du Dr Albert Schweitzer, 91420, Morangis, France.

Emmanuel Bonnet, IRD, UMR 215 Prodig, 5, cours de Humanités, Cedex, F-93 322, Aubervilliers, France.

Adama Faye, Institut de Santé et Développement, Université Cheikh Anta Diop, BP 16390, Fann-Dakar, Sénégal.

Funding

This research was conducted as part of the ARIACOV programme (Appui à la Riposte Africaine à l'épidémie de Covid-19), which receives funding from the French Development Agency through the ‘COVID-19 - Santé en commun’ initiative.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the National Ethics Committee for Health Research in Senegal (SEN/20/23).

Data availability

Data are available upon request to the authors.

References

- 1. Wilder-Smith A, Cook AR, Dickens BL.. Institutional versus home isolation to curb the COVID-19 outbreak – authors’ reply. Lancet North Am Ed. 2020;396(10263):1632–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Quilty BJ, Clifford S, Hellewell Jet al. Quarantine and testing strategies in contact tracing for SARS-CoV-2: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(3):e175–e183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gouvernement du Sénégal . Conseil des ministres du 04 mars 2020. 2020 [cité 24 janv 2021]. Available at https://www.sec.gouv.sn/actualité/conseil-des-ministres-du-04-mars-2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4. République du Sénégal . CORONAVIRUS : Le President de la République Macky Sall prend plusieurs mesures. 2020 [cité 18 nov 2020]. Available at http://www.mesr.gouv.sn/index.php/2020/03/15/coronavirus-le-president-de-la-republique-macky-sall-prend-plusieurs-mesures/. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Centre des Opérations d'Urgence Sanitaire. Rapport de situation no 40 du 23 juillet 2020. Dakar, Sénégal ; 2020[cité 18 Nov 2020]. Available at https://www.sante.gouv.sn/sites/default/files/SITREP_40_COVID_SN%20.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ministère de la Santé et de l'Action Sociale. Communiqué 22 du 23 03 2020. Dakar, MSAS; 2020 [cité 10 sept 2020]. Available at http://www.sante.gouv.sn/sites/default/files/COMMUNIQUE 22 du 23 mars 2020.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ministère de la Santé et de l'Action Sociale. Communiqué 222 du 09 10 2020. Dakar, MSAS; 2020 [cité 9 oct 2020]. p. 2. Available at http://www.sante.gouv.sn/sites/default/files/Communiqué 222 du 09 10 2020.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ministère de la Santéet de l'Action Sociale . Communiqué 67 du 07 05 2020. Dakar, MSAS; 2020. [cité 10 janv 2021]. Available at https://www.sante.gouv.sn/sites/default/files/COMMUNIQUE%2067%20DU%2007%20MAI%202020.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Centre des Opérations d'Urgence Sanitaire. Procédure Opératoire Normalisée (PON) : PRISE EN CHARGE DE CAS SIMPLES À DOMICILE DANS LE CONTEXTE DU COVID-19. Dakar, Sénégal; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Organisation Mondiale de la Santé . Soins à domicile pour les patients COVID-19 qui présentent des symptômes bénins, et prise en charge de leurs contacts. Genève, Suisse; 2020. [cité 20 nov 2020]. Available at https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331527. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Faye SL. L’« exceptionnalité » d'Ebola et les « réticences » populaires en guinée-conakry. Réflexions à partir d'une approche d'anthropologie symétrique. Anthropologie et Santé. 2015;11. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Syed Mohammed . 94% des patients COVID traités en isolement à domicile, montre une enquête - The Hindu. The Indu. 2020 [cité 17 déc 2020]. Available at https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Hyderabad/94-covid-patients-treated-in-home-isolation-shows-survey/article32663377.ece. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gouvernement Australien . Home isolation guidance when unwell (suspected or confirmed cases). Canberra, Australie; 2020. [cité 18 janv 2021]. Available at https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/02/coronavirus-covid-19-information-about-home-isolation-when-unwell-suspected-or-confirmed-cases.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gouvernement Canadien . Mise à jour : Prise en charge par la santé publique des cas de COVID-19 et des contacts qui y sont associés - Canada.ca. 2020 [cité 17 déc 2020]. Available at https://www.canada.ca/fr/sante-publique/services/maladies/2019-nouveau-coronavirus/professionnels-sante/directives-provisoires-cas-contacts.html. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ayaz CM, Dizman GT, Metan G, Alp A, Unal S.. Out-patient management of patients with COVID-19 on home isolation. Infezioni in Medicina. 2020;28(3):351–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. INSERM . Coronavirus et Covid-19. 2020 [cité 8 janv 2021]. Available at https://www.inserm.fr/information-en-sante/dossiers-information/coronavirus-sars-cov-et-mers-cov. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dickens BL, Koo JR, Wilder-Smith A, Cook AR.. Institutional, not home-based, isolation could contain the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet North Am Ed. 2020;395(10236):1541–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kucharski AJ, Klepac P, Conlan AJKet al. Effectiveness of isolation, testing, contact tracing, and physical distancing on reducing transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in different settings: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(10):1151–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. MacIntyre CR. Case isolation, contact tracing, and physical distancing are pillars of COVID-19 pandemic control, not optional choices. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(10):1105–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Organisation Mondiale de la Santé . Home care for patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 and management of their contacts. Genève, Suisse: WHO; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Agence Nationale de Statistique et de la Démographie. 2020 [cité 19 nov 2020]. Available at http://www.ansd.sn/. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ministère de Santé et de l'Action Sociale. Sénégal: Plan National de Développement Sanitaire et Social (PNDSS). Dakar, Sénégal; 2019. [cité 18 janv 2021]. Available at https://sante.gouv.sn/sites/default/files/1%20MSAS%20PNDSS%202019%202028%20Version%20Finale.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Centre des Opérations d'Urgence Sanitaire. Rapport de situation no 78 du 18 janvier 2021. Dakar, Sénégal; 2021[cité 20 janv 2021]. Available at https://www.sante.gouv.sn/sites/default/files/SITREP%2078%20Covid-19%2018-01-2021.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cissé M. Sénégal. Covid-19: le nombre de lits augmenté en urgence face à l’évolution inquiétante de la pandémie. Le360 Afrique. 2020 [cité 24 janv 2021]. Available at https://afrique.le360.ma/senegal/societe/2020/05/01/30412-senegal-covid-19-le-nombre-de-lits-augmente-en-urgence-face-levolution-inquietante-de-la-pandemie. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marbot O. Nombre de lits de réanimation et de respirateurs : où en est l'Afrique ? Jeune Afrique. 2020 [cité 24 janv 2021]. Available at https://www.jeuneafrique.com/924087/societe/nombre-de-lits-de-reanimation-et-de-respirateurs-ou-en-est-lafrique/ [Google Scholar]

- 26. Soumaré M. Sénégal : l'arrivée de Free est-elle une bonne nouvelle pour les consommateurs ? JeuneAfrique.com. 2019 [cité 18 juill 2022]. Available at https://www.jeuneafrique.com/843612/societe/senegal-larrivee-de-free-est-elle-une-bonne-nouvelle-pour-les-consommateurs/. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Greene J. Toward a methodology of mixed methods social inquiry. Research in the Schools. 2006;13(1):93–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Deville JC. Une théorie des enquêtes par quotas.pdf. Techniques d'enquête, Statistique Canada. 1991;12(2):177–95. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ardilly P. Les techniques de sondage. Paris, France: Technip; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ridde V, Kane B, Gaye Iet al. Acceptability of government measures against COVID-19 pandemic in Senegal: a mixed methods study. PLOS Global Public Health. 2022;2(4):e0000041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pigeon-Gagné É, Hassan G, Yaogo M, Ridde V.. An exploratory study assessing psychological distress of indigents in burkina faso: a step forward in understanding mental health needs in west Africa. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16(1):143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ouédraogo S, Ridde V, Atchessi Net al. Characterisation of the rural indigent population in Burkina Faso: a screening tool for setting priority healthcare services in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Open. 2017;7(10):9–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bruchon-Schweitzer M, Boujut E.. Psychologie de la santé - concepts, méthodes et modèles. 2e édition. Paris, France: DUNOD; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Santé Organisation Mondiale de la . Wellbeing measures in primary health care/the depcare project. Report on a WHO Meeting. Genève, Suisse: WHO; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S.. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd Ed. New York, NY: Wiley-Interscience; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang Z. Model building strategy for logistic regression: purposeful selection. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4(6):4–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Centre des Opérations d'Urgence Sanitaire . Rapport de situation no 35 du 06 juillet 2020. Dakar, Sénégal; 2020. [Cité 18 janv 2021]. Available at https://www.sante.gouv.sn/sites/default/files/SITREP_35_COVID_SN%20.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Desclaux A, Badji D, Ndione AG, Sow K. Accepted monitoring or endured quarantine? Ebola contacts’ perceptions in senegal. Soc Sci Med. 2017;178:38–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Smith LE, Potts HW, Amlȏt R, Fear NT, Michie S, Rubin GJ. Adherence to the test, trace and isolate system: results from a time series of 21 nationally representative surveys in the UK (the COVID-19 rapid survey of adherence to interventions and responses [CORSAIR] study). medRxiv. 2020;1–47. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Webster RK, Brooks SK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Rubin GJ.. How to improve adherence with quarantine: rapid review of the evidence. Public Health. 2020;182:163–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ridde V, Faye A. Challenges in Implementing the National Health Response to COVID-19 in Senegal. Glob Implement Res Appl. 2022;2(3):219–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liu XJ, Mesch GS.. The adoption of preventive behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic in China and Israel. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(19):1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Guglielmi S, Dotti Sani GM, Molteni Fet al. Public acceptability of containment measures during the COVID-19 pandemic in italy: how institutional confidence and specific political support matter. Int J Sociol Soc Policy. 2020;40:1065–85. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Organisation Mondiale de la Santé . Mise à jour de la stratégie COVID-19. Genève, Suisse; 2020. [cité 24 janv 2021]. Available at https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/strategy-update-french.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ibrahim AA, Ali KM, Mohammed AEet al. Knowledge, counseling and test acceptability regarding AIDS among Knowledge, counseling and test acceptability regarding AIDS among secondary school students, Khartoum, Sudan. Int J Appl Res. 2017;3(11):448–51. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hesse E. Les connaissances relatives à la transmission du virus du SIDA. Bruxelles, Belgique; 2008. [cité 25 janv 2021]. Available at https://www.wiv-isp.be/epidemio/epifr/crospfr/hisfr/his08fr/r2/8.les_connaissainces_relatives_a_la_transmission_du_SIDA_r2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nestour A Le, Samba M, Laura M.. Enquête téléphonique sur la crise du Covid au Sénégal. 2020. [cité 13 fev 2021]. Available at https://crdes.sn/assets/publications/Enquete_telephonique_sur_la_crise_du_Covid_au_Senegal.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tchouassi G. Les besoins en informations dans les entreprises. Revue Congolaise de Gestion. 2017;24:63. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Diepeveen S, Ling T, Suhrcke M, Roland M, Marteau TM.. Public acceptability of government intervention to change health-related behaviours: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Organisation Mondiale de la Santé. COVID-19 : ce qu'il faut savoir. Organisation Mondiale de la Santé. 2020 [cité 18 nov 2020]. Available at https://www.who.int/fr/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/q-a-coronaviruses?gclid=EAIaIQobChMInP6JweTF7AIVTPlRCh34kgtjEAAYASAAEgJe0vD_BwE. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Emedia . PR SEYDI : « LES RÉSULTATS DE LA CHLOROQUINE SONT ABSOLUMENT ENCOURAGEANTS ». Emedia. 2020 [cité 19 nov 2020]. Available at http://emedia.sn/VIDEO-PR-SEYDI-LES-RESULTATS-DE-LA-CHLOROQUINE-SONT-ABSOLUMENT-ENCOURAGEANTS.html. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Emedia . CHLOROQUINE & AZYTHROMICINE : Pr SEYDI VALIDE À NOUVEAU LE « PROTOCOLE DE RAOULT ». Emedia. 2020 [cité 19 nov 2020]. Available at http://www.emedia.sn/CHLOROQUINE-AZYTHROMICINE-Pr-SEYDI-VALIDE-A-NOUVEAU-LE-PROTOCOLE-DE-RAOULT.html. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Faye M, Diatta JS. La communication du gouvernement sénégalais à l’épreuve de la covid-19. Akofena. 2020;3:255–66. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Quenum GGY, Ertz M.. Les stratégies d ’ adaptation dans la consommation lors de la crise de la COVID-19 : quel espoir pour la consommation responsable ? Organisation Territoires. 2020;29(3):87–9. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request to the authors.