Abstract

A recent full-dimensional Δ-Machine learning potential energy surface (PES) for ethanol is employed in semiclassical and vibrational self-consistent field (VSCF) and virtual-state configuration interaction (VCI) calculations, using MULTIMODE, to determine the anharmonic vibrational frequencies of vibration for both the trans and gauche conformers of ethanol. Both semiclassical and VSCF/VCI energies agree well with the experimental data. We find significant mixing between the VSCF basis states due to Fermi resonances between bending and stretching modes. The same effects are also accurately described by the full-dimensional semiclassical calculations. These are the first high-level anharmonic calculations using a PES, in particular a “gold-standard” CCSD(T) one.

Introduction

From the very early days of quantum mechanics, the holy grail of theoretical chemists has been to put quantum mechanics to use as a computational tool that would some day rival the precision of experiment. The foundational, specific goal has been to develop first-principles potentials, i.e., from quantum mechanics, that govern nuclear motion. Progress in doing this for ever-larger molecules has been dramatic in the past 15 or so years.

Developing high-dimensional, ab initio-based potential energy surfaces (PESs) remains an active area of theoretical and computational research. Significant progress has been made in the development of machine learning (ML) approaches to generate potential energy surfaces (PESs) for systems with more than five atoms, based on fitting thousands of CCSD(T) energies.1−4 The quantum chemical methods capturing a substantial part of electron correlation, such as coupled-cluster with singles and doubles (CCSD), coupled-cluster with perturbative triples [CCSD(T)], and so on, have a formidable scaling, leading to the requirement of high speed processor, memory, and secondary storage. Thus, there is a bottleneck for developing the PES at high level theory with the increase of molecular size. Due to the steep scaling of the gold standard CCSD(T) theory (∼N7, N being the number of basis functions), it is computationally demanding to build PESs of systems with more than 9–10 atoms. (Many researchers do not consider this number of atoms as a “large molecule”; however, it is used here as a computational boundary for the CCSD(T) method.) Therefore, people are bound to use low-level electronic structure methods such as density functional theory (DFT) and Møller–Plesset second-order perturbation theory (MP2) to generate PESs for large molecules.

The PESs of molecules having more than 10 atoms using CCSD(T) level of theory are generally conspicuous by their absence. One 10-atom PES using the method we are aware of is the formic acid dimer (HCOOH)2,5 which contains 6 heavy atoms. It was developed by Bowman and co-workers in 2016. This was a major computational effort at the CCSD(T)-F12a/haTZ (VTZ for H and aVTZ for C and O) level of theory, which was a fit to 13475 electronic energies. A 9-atom PES for the chemical reaction Cl + C2H6 was recently developed by Papp et al. using a composite MP2/CCSD(T) method.6 Examples of potentials for 6- and 7-atom chemical reactions which are fits to tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of CCSD(T) energies have also been reported.1,3,4,7,8

The increasing dimensionality of the PES with the increase in number of atoms requires large training data sets to fit the PES. Thus, given the intense interest and progress in moving to larger molecules and clusters, where high-level methods are prohibitively expensive, the use of lower-level methods such as DFT and MP2 is understandable. These methods also provide analytical gradients, and this is an important source of data needed for larger systems. Our group has made use of the permutationally invariant polynomial (PIP) approach for developing PESs of N-methylacetamide,9,10 glycine,11 and tropolone.12

To circumvent this bottleneck, machine learning (ML) approaches are being used to bring a PES based on a low-level of electronic structure theory (DFT or MP2) to a higher level (CCSD(T)) one. There are two popular methods currently being investigated to achieve this goal. One is the “transfer learning” (TL), and the other is the “Δ-machine learning” (Δ-ML).

TL has been developed extensively in the context of artificial neural networks,13 and much of the work in that field has been brought into chemistry.14−18 The basic idea of TL is that a fit obtained from one source of data (perhaps a large one) can be corrected for a related problem by using limited data and by making hopefully small training alterations to the parameters obtained in the first fit. Therefore, in the present context of PES fitting, a ML-PES fit to low-level electronic energies/gradients can be reused as the starting point of the model for an ML-PES with the accuracy of a high-level electronic structure theory. As noted, this is typically done with artificial neural networks, where weights and biases trained on lower-level data hopefully require minor changes in response to additional training using high-level data. Recently, Meuwly and co-workers applied TL to improve the MP2-based neural network PESs for malonaldehyde, acetoacetaldehyde, and acetylacetone using thousands of local CCSD(T) energies.18

The other approach is Δ-machine learning (ML). In this approach a correction is made to a property data set obtained using an efficient, low-level ab initio theory such as DFT or MP2.15−19 We applied this Δ-ML approach to correct an numbers of PESs based on DFT electronic energies and gradients.20 Initially, this was successfully done for CH4 and H3O+ and for 12-atom N-methylacetamide.20 For N-methylacetamide, the PES included both the cis and trans isomers and the saddle points separating them. More recently, Δ-ML was extensively applied to the 15-atom acetylacetone (AcAc, CH3COCH2COCH3) molecule. This not only developed a full-dimensional PES at CCSD(T) level but also was successfully applied to compute the quantum zero point energy and ground state wave function using diffusion Monte Carlo (DMC) algorithm as well as to determine the tunneling splitting of H-transfer process.21 In all cases, a relatively small number of coupled cluster energies were obtained over the same large span of configurations used to get the lower-level DFT PES.

Our most recent application of Δ-ML has been to a full-dimensional PES for the 9-atom ethanol (CH3CH2OH) molecule at the CCSD(T) level.22 Ethanol is widely used as a solvent in chemical reactions, and it has great importance in combustion chemistry. Ethanol is the leading biofuel in the transportation sector, where it is mainly used in a form of reformulated gasoline.23,24 Thus, the study of ethanol chemistry in internal combustion engines is of high interest from scientific, industrial, and environmental perspectives. Ethanol exists as a mixture of trans or anti and gauche (±) conformers in both solid, liquid, and gaseous state.25−27 It is well-known that the energy gap between the two conformers is quite small; experimentally, it is observed that ΔG is 0.12 (0.02) kcal/mol in favor of the trans conformer.26 Ethanol also has a 3-fold methyl torsional potential which makes its potential surface much more complex. These aspects have been investigated when presenting the new PES. Diffusion Monte Carlo (DMC) calculations performed on the new PES have shown that the global minimum is of the trans configuration even when starting from the gauche geometry. In this work we complete our study of ethanol by examining the fundamental frequencies of vibration of both conformers, which are expected to be influenced by quantum state mixing and Fermi resonances. To accomplish this task we employ full-dimensional semiclassical (SC) calculations and vibrational self-consistent field (VSCF) and virtual-state configuration interaction (VCI) calculations using MULTIMODE.

The paper is organized as follows. In the next section we briefly describe the PES employed and then provide theoretical and computational details about MULTIMODE and Semiclassical simulations. This is followed by the “Results and Discussion” section in which we compare the calculated frequencies of vibration with experimental data. Finally, the “Summary and Conclusions” section ends the paper.

Theory and Computational Details

CCSD(T) PES of Ethanol

The full-dimensional CCSD(T) PES of ethanol used here has been recently reported,22 so we give only a brief summary here. The development of this PES can be divided into two parts: low-level DFT PES (VLL) and a correction PES (ΔVCC–LL). Initially, a low-level DFT PES is developed for ethanol using the efficient B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) level of theory, and then a correction is made using a sparse set of a relatively small number of ab initio CCSD(T) energies to determine the Δ-ML surface using the simple equation.20

| 1 |

where VLL→CC is the corrected PES, VLL is a PES fit to low-level electronic data, and ΔVCC–LL is the correction PES based on high-level coupled cluster energies. The assumption underlying the hoped-for small number of high-level energies is that the difference ΔVCC–LL is not as strongly varying as VLL with respect to nuclear configuration.

This VLL PES is a permutationally invariant polynomial fit to 8500 energies and their corresponding gradients at B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) level of theory spanning the energy range of 0–35 000 cm–1. For this fit, we used a maximum polynomial order of 4 with permutational symmetry of 321111, leading to a total of 14752 PIP basis functions and linear coefficients whose values were determined by linear least-squares regression. More details of this PES can be found elsewhere.28

To develop the correction PES, we train ΔVCC–LL on the difference between the CCSD(T)-F12a/aug-cc-pVDZ and DFT absolute energies for 2069 geometries. A low-order PIP fit was employed because the difference ΔVCC–LL is not as strongly varying as VLL with respect to the nuclear configuration. We used maximum polynomial order of 2 with permutational symmetry 321111 to fit the training data set which leads to a total of 208 PIP bases. The PIP basis to fit these VLL and ΔVCC–LL PESs were generated using our latest MSA software.29,30 The corrected PES was analyzed and verified previously and already used in unrestricted diffusion Monte Carlo (DMC) and semiclassical calculations to compute accurate zero-point energies (ZPEs) of the trans and gauche conformers. Details of this PES and analyses can be found in ref (22). Here we use this PES in new vibrational calculations of excited states. These are done using MULTIMODE VSCF/VCI and adiabatically switched (AS) semiclassical initial value representation (SCIVR) methods, which are briefly described next.

MULTIMODE Calculations

Postharmonic quantum methods based on vibrational self-consistent field (VSCF) and virtual-state configuration interaction (VCI) approaches have been known for almost 50 years. These methods have been implemented in our software called MULTIMODE. First, we present a brief recap of the VSCF31,32 and VSCF/VCI scheme33 in MULTIMODE.34−36 The computational code is based on the rigorous Watson Hamiltonian37 in mass-scaled normal coordinates, Q, for nonlinear molecules. This Hamiltonian is given by

| 2 |

where α(β) represent the x, y, z coordinates, Ĵα and π̂α are the components of the total and vibrational angular momenta respectively, μαβ is the inverse of effective moment of inertia tensor, and V(Q) is the full potential in terms of normal coordinates. The number of normal modes is denoted by F, and for nonlinear molecules F equals 3N – 6. In many applications of this Hamiltonian in the literature, the vibrational angular momentum terms are neglected and this approximation leads to an inaccurate result. Therefore, we include these terms in the MULTIMODE software.

In general there are two major bottlenecks in applications to the VSCF/VCI scheme. One is the numerical evaluation of matrix elements (multidimensional integrals) and the second is the size of the H-matrix. Both naively have exponential dependence on the number of normal coordinates. An effective approach to deal with exponential scaling of matrix elements we represent the full potential in a hierarchical n-mode representation (nMR).34 In normal coordinates, this representation is given by

|

3 |

where Vi(1)(Qi) is the one-mode potential, i.e., the 1D cut through the full-dimensional PES in each mode, one-by-one, Vij(Qi,Qj) is the intrinsic 2-mode potential among all pairs of modes, and so on. Here, intrinsic means that the any n-mode term is zero if any of the arguments is zero. Also, each term in the representation is in principle of infinite order in the sense of a Taylor series expansion. So for example, V(1)(Q) might look like a full Morse potential.

This representation has been used for nearly 20 years by a number of research groups; a sample of these are refs (34−36) and (38−41). It continues to be actively used in a variety of applications and theoretical developments.42−47 In MULTIMODE the maximum value of n is 6. However, from numerous tests it appears that a 4MR typically gives energies that are converged to within roughly 1–5 cm–1.48−50 Thus, we generally use 4MR with an existing full-dimensional PES and this is also done here.

The second major bottleneck to all VCI calculations is the size of the H-matrix, which as noted already can scale exponentially with the number of vibrational modes. There are many strategies to deal with this. Basically, they all limit the size of the excitation space, with many schemes taken from electronic structure theory. For example, the excitation space can be limited by using the hierarchical scheme of single, double, triple, and further excitations. MULTIMODE uses this among other schemes and can consider up to quintuple excitations. A major difference with electronic structure theory is that the nuclear interactions go beyond two-body. This is immediately clear from the n-mode representation. Thus, MULTIMODE tailors the excitation scheme for each term in this representation. Other schemes to prune the CI basis have been suggested, and the reader is referred to reviews40,42,48,51−56 for more details.

We note that the above basic VSCF/VCI scheme with the n-mode representation has been implemented in Molpro by Rauhut and co-workers with the option to obtain the electronic energies directly on n-mode grids, with n up to 4 or from an existing potential.57 Of course numerous enhancements and modifications to the basic scheme can be found there.

Finally, some comments on the limitations of rectilinear normal modes and thus the Watson Hamiltonian are in order for ethanol, which has large amplitude torsional modes. These are not expected to be accurately described, especially for excited states which will exhibit large amplitude curvilinear motion. We do note that the reaction path version of MULTIMODE58 is able to describe these. However, because such motion is not the focus of the present work, we do not use this version, as it is also more computationally demanding than the version we adopt here. Thus, the calculations we present are more reliable quantitatively in the high-frequency region than in the low-frequency region.

Semiclassical Theory and Calculations

An alternative approach we employ to calculate the anharmonic frequencies is represented by the adiabatically switched (AS) semiclassical initial value representation (SCIVR) technique.59−61 AS SCIVR is a recently developed two-step procedure able to describe quantum effects starting from classical trajectories. Therefore, AS SCIVR is a member of the family of semiclassical methods (see, for instance, refs (62−70)), and it features a characteristic way to determine the starting conditions of the semiclassical dynamics. In AS SCIVR, one starts from harmonic quantization and slowly, adiabatically, switches on the actual molecular Hamiltonian. The final geometry and momenta of the adiabatic switching run serve as starting conditions for the subsequent semiclassical dynamics trajectory. This procedure is applied to a distribution of harmonically quantized starting conditions.

The adiabatic switching Hamiltonian is71−73

| 4 |

where λ(t) is with switching function

| 5 |

Hharm is the harmonic Hamiltonian built from the harmonic frequencies of vibration, and Hanh is the actual molecular vibrational Hamiltonian. We chose TAS equal to 25000 a.u. (about 0.6 ps), and we employed time steps of 10 a.u. for a total of 4400 trajectories.

Once the adiabatic switching run is over, the trajectories are evolved according to Hanh for another 25000 a.u. with same step size to collect the dynamical data needed for the semiclassical calculation. For this purpose we use Kaledin and Miller’s time-average formula

| 6 |

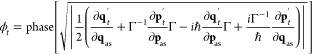

where Ias(E) indicates that a vibrational spectral density is calculated as a function of the vibrational energy E. Ias is peaked at the eigenvalues of the vibrational Hamiltonian, the lowest one being the ZPE. Frequencies of vibration are obtained by difference between the relevant eigenvalues and the ZPE. In eq 6Nv is the number of vibrational degrees of freedom of the system, i.e., 21 in the case of ethanol. T is the total evolution time of the dynamics for the semiclassical part of the simulation. As anticipated, we chose T equal to 25000 a.u. with a time step size of 10 a.u. (pt′, qt) is the instantaneous full-dimensional phase space trajectory started at time 0 from the final adiabatic-switching phase space condition (pas, qas). St is the classical action along the semiclassical trajectory, and ϕt is the phase of the Herman–Kluk pre-exponential factor based on the elements of the stability matrix and defined as

|

7 |

where Γ is an Nv × Nv matrix usually chosen to be diagonal with elements numerically equal to the harmonic frequencies. Based on Liouville’s theorem, the stability (or monodromy) matrix has the property to have its determinant equal to 1 along the entire trajectory. However, classical chaotic dynamics can lead to numerical inaccuracies in the propagation, so, following a common procedure in semiclassical calculations, we have rejected the trajectories based on a 1% tolerance threshold on the monodromy matrix determinant value. Finally, the working formula is completed by the quantum mechanical overlap between a quantum reference state |Ψ⟩ and a coherent state |g⟩ with the following representation in configuration space

| 8 |

The reference state |Ψ⟩ is usually chosen to be itself a coherent state. In eq 6 |Ψ⟩ is written as |Ψ(peq,qeq)⟩, where peq stands for the linear momenta obtained in harmonic approximation setting the geometry at the equilibrium one (qeq).

Results and Discussion

Our CCSD(T)-level PES for ethanol22 has been employed for all results presented in this section. The lowest quantum vibrational energy level of a molecule is known as the zero-point energy. A calculation of the ZPE and the associated wave function can be obtained by means of Diffusion Monte Carlo (DMC) calculations. When these are performed for the two ethanol conformers, the same ZPE value is found (17321 cm–1), and the wave function reveals the leaky nature of this molecule. As shown in Figure 1, the ground state resembles the trans conformer independent of the starting conformer in the DMC calculation, but substantial delocalization to the gauche conformer is present.22 The leaky nature of the ZPE wave function is responsible for the difficulties to isolate the conformers even at very low temperature, but these results do not preclude concentrated probability density for either conformer for excited states. Indeed, Raman, IR, and spectroscopy experiments implicate the presence of the two conformers.74 For instance, a band contour is typical of the signal of the OH stretches and several simplified and reduced-dimensional potentials have been proposed to confirm the experimental assignments.75,76 However, these calculations need refinement. Therefore, availability of a full-dimensional and very accurate PES has stimulated us to calculate the fundamental frequencies of vibration for both trans- and gauche-ethanol.

Figure 1.

Geometry and ground state wave function for trans- and gauche-ethanol. Reproduced with permission from ref (22). Copyight 2022 American Chemical Society.

MULTIMODE calculations are performed using version 5.1.4.31,34,36 For all the calculations, a four-mode representation of the potential in mass-scaled normal coordinates and a three-mode representation of the effective inverse moment of inertia for the vibrational angular momentum terms in the exact Watson Hamiltonian are used.37 The formalism is based on CI from the virtual space of the ground vibrational state VSCF Hamiltonian. Here we explore reduced-mode coupling models, i.e., 11- and 15-mode models, where these sets of modes start with the highest frequency OH-stretch and proceed in decreasing frequency. In both cases the maximum mode combination excitations are 10 10 10 8, which means that single through triple excitations extend to a maximum sum of quanta of 10, and for quadruple excitations the maximum is 8. This excitation space leads to CI matrix sizes of 45486 and 155026 for 11- and 15-mode calculations, respectively. We compute 200 CI vibrational states up to the energy of 4000 cm–1.

AS SCIVR calculations are performed as described in the previous section. The rejection rate due to chaotic trajectories is found to be about 60%. Therefore, calculations are based on about 2000 complete trajectories, which is enough for AS SCIVR to warrant reliability and accuracy of results given the fast convergence of the method.59

Rejection is mainly due to the CH3 rotor motion. Rejection of these trajectories may lead to some inaccuracies in the SC estimate of rotor motions, but these are low-frequency ones. The reported results demonstrate this effect has no influence on the SC description of higher frequency vibrations.

Tables 1 and 2 show MULTIMODE and semiclassical AS SCIVR anharmonic frequencies with the corresponding experimental and previous scaled harmonic ones.76,77 First, note that for many states the 11- and 15-mode calculations are with a few cm–1 of each other. For those cases where larger differences are seen, the 15-mode results are closer to experiment. There are more of these instances for gauche than trans. Also, the same set of states labeled as “mixed” (to be discussed in more detail below) appear in both sets of calculations. Second, there is generally good agreement between MULTIMODE and AS SCIVR frequencies as well as experimental ones. Third, the scaled harmonic results, from two groups,76,77 are also in good agreement with the experiment, but this is the result of empirical scaling factors. The scale factors are different and this is because of significant differences in harmonic frequencies. For instance, the harmonic frequencies for the trans OH-stretch are, in cm–1, 3779(MP2)77 and 3756(DFT),76 and for the gauche OH-stretch they are 3772(MP2)77 and 3740(DFT).76 None of these agree well with our recently reported corresponding values of 3862(3853) and 3845(3837).22 These are from the PES (in parentheses we give the direct calculations at the CCSD(T)-F12/aug-cc-pVDZ level of theory). One more example is for the trans CH2–symmetric stretch (sstr): 3062(MP2)77 and 2926 (DFT).76 These differ substantially from the PES and direct CCSD(T) values of 2995 and 3001, respectively.

Table 1. Vibrational Frequencies for trans-Ethanola.

| mode | scl-harm (ref (77))b | scl-harm (ref (76))c | MM (11 modes) | MM (15 modes) | AS SCIVR | expt (ref (77)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7(CO–str) | 1090 | 1093 | **** | 1101 | 1088 | 1090 (1093) |

| 8(CH2–rck) | 1160 | 1150 | **** | 1160 | 1148 | 1166 |

| 9(COH–bnd) | 1248 | 1251 | **** | 1251 | 1242 | 1241 (1245) |

| 10(CH2–twst) | 1268 | 1269 | **** | 1276 | 1271 | 1275 |

| 11(CH3–sdef) | 1375 | 1375 | 1367 | 1370 | 1363 | 1367 |

| 12(CH2–wag) | 1431 | 1423 | 1427 | 1426 | 1420 | 1450 (1430) |

| 13(CH3–adef′) | 1455 | 1458 | 1444 | 1443 | 1440 | 1455 |

| 14(CH3–adef″) | 1472 | 1476 | 1459 | 1459 | 1456 | 1480 (1460) |

| 15(CH2–sdef) | 1503 | 1500 | 1491 | 1489 | 1481 | 1500 (1460) |

| 16(CH2–sstr) | 2872 | 2865 | 2810d | 2811d | 2881 | 2888 (2887) |

| 17(CH2–astr) | 2912 | 2887 | 2864d | 2884d | 2888 | 2901 |

| 18(CH3–sstr) | 2926 | 2941 | 2939d | 2937d | 2933 | 2922 |

| 19(CH3–astr″) | 3012 | 3011 | 2976d | 2977d | 2983 | 2987 |

| 20(CH3–astr′) | 3022 | 3014 | 2978d | 2981d | 2986 | 2992 |

| 21(OH–str) | 3585 | 3678 | 3679 | 3672 | 3676 | 3676 (3675) |

| MAE | 13 | 12 | 19 | 13 | 8 |

Harmonic, MULTIMODE (4MR), AS SCIVR, and experimental IR and Raman gas values. Numbers in parentheses are from Raman experiment. MAE is the mean absolute error with respect to the closest experimental frequency.

Scaled harmonic at MP2/6-31G(d) level. Scaling factors: 1.0 for heavy atom bend; 0.88 for CH stretches (str) and deformations (def); 0.90 for all other modes.

Scaled harmonic at DFT/B97-3c level. Scaling factor 0.979.

Table 2. Vibrational Frequencies for gauche-Ethanola.

| mode | scl-harm (ref (77))b | scl-harm (ref (76))c | MM (11 modes) | MM (15 modes) | AS SCIVR | expt (ref (77)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7(CO–str) | 1063 | 1064 | **** | 1085 | 1060 | 1066 |

| 8(CH2–rck) | 1119 | 1129 | **** | 1124 | 1115 | 1117 |

| 9(CH2–twst) | 1259 | 1256 | **** | 1259 | 1247 | 1249 |

| 10(COH–bnd) | 1345 | 1348 | **** | 1337 | 1332 | 1342 |

| 11(CH2–wag) | 1373 | 1376 | 1370 | 1370 | 1369 | 1373 |

| 12(CH3–sdef) | 1396 | 1391 | 1393 | 1393 | 1386 | 1394 (1430) |

| 13(CH3–adef′) | 1461 | 1464 | 1448 | 1447 | 1448 | 1460 |

| 14(CH3–adef″) | 1466 | 1467 | 1454 | 1454 | 1451 | 1465 (1460) |

| 15(CH2–sdef) | 1490 | 1489 | 1480 | 1480 | 1475 | 1493 (1460) |

| 16(CH2–sstr) | 2886 | 2874 | 2867d | 2880d | 2885 | 2912 |

| 17(CH3–sstr) | 2912 | 2924 | 2874d | 2923d | 2909 | 2936 |

| 18(CH2–astr) | 2978 | 2965 | 2927d | 2950d | 2957 | 2972 |

| 19(CH3–astr′) | 2996 | 2990 | 2958d | 2979d | 2977 | 2987 |

| 20(CH3–astr″) | 3015 | 3010 | 2976d | 2978d | 2985 | 2994 |

| 21(OH–str) | 3579 | 3662 | 3659 | 3653 | 3655 | 3662 |

| MAE | 13 | 8 | 22 | 12 | 10 |

Harmonic, MULTIMODE (4MR), AS SCIVR, and experimental IR gas values. Experimental values in parentheses refer to the Raman experiment. MAE is the mean absolute error with respect to the closest experimental frequency.

Scaled harmonic at MP2/6-31G(d) level. Scaling factors: 1.0 for heavy atom bend; 0.88 for CH stretches (str) and deformations (def); 0.90 for all other modes.

Scaled harmonic at DFT/B97-3c level. Scaling factor 0.979.

A more general critique of using scaled frequencies in the present case is the significant mixing in a number of CH2 and CH3 stretches noted in the footnote to these tables. Details of this mixing are given in Tables 3 and 4. There the three largest VCI coefficients in the expansion basis for the 15-mode calculations are given for each “MULTIMODE frequency”, and the normal mode vectors for trans ethanol are depicted in Figure 2. The ones for gauche ethanol are quite similar. In general the nominal assignment would be based on the largest coefficient. However, as seen there are several states where there are two basis functions with nearly equal coefficients. One example in Table 3 is for the overtone of trans CH2–wag, denoted 2ν12, with the fundamental of trans CH2–sstr, denoted ν16. This is an example of classic 2:1 Fermi resonance, where the corresponding harmonic frequencies (see Table 1 of ref (22)) are close to the 1:2 ratio. The other resonance is with the combination band ν12 + ν11. Note that the sum of the squares of these coefficients adds to 0.86, so there are in fact other basis functions that make up the remainder of the expansion of this anharmonic eigenstate. It is worth mentioning that we also found similar VCI coefficients for the 11-modes calculations, which demonstrates that these resonances are present in both MULTIMODE calculations. However, for some states the coupling modes are different compared to the 15-mode calculation. This is because the low frequency bending, rocking, and twisting modes are playing an important role in some resonance states in 15-mode calculation, but they are completely missing in the 11-mode calculation.

Table 3. Three Largest VSCF/VCI Expansion Coefficients of Indicated Energies (cm–1) Frequencies for trans-Ethanol.

|

trans-ethanol | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| MULTIMODE frequency | coupling modes | quanta | coeff. |

| 2811 | CH2–wag | 2ν12 | 0.6051 |

| CH2–sstr | ν16 | –0.5347 | |

| CH3–sdef + CH2–wag | ν11 + ν12 | –0.4571 | |

| 2884 | CH2–astr | ν17 | –0.8634 |

| CH2–twst + CH2–wag | ν10 + ν12 | 0.2818 | |

| CH2–rck + CH2–sdef | ν8 + ν15 | –0.2263 | |

| 2937 | CH3–sstr | ν18 | 0.6277 |

| CH3–adef″ | 2ν14 | –0.5442 | |

| CH3–adef′ | 2ν13 | 0.3019 | |

| 2977 | CH3–astr″ | ν19 | 0.8309 |

| CH3–adef″ + CH2–sdef | ν14 + ν15 | –0.3612 | |

| CH3–adef″ | 2ν14 | –0.2379 | |

| 2981 | CH3–astr′ | ν20 | 0.9237 |

| CH3–adef′ + CH3–adef″ | ν13 + ν14 | 0.1871 | |

| CH2–wag + CH3–adef′ | ν12 + ν13 | –0.1319 | |

Table 4. Three Largest Absolute Magnitude Coupling Coefficients of MULTIMODE Frequencies for gauche-Ethanol.

|

gauche-ethanol | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| MULTIMODE frequency | coupling modes | quanta | coeff. |

| 2880 | CH2–sstr | ν16 | 0.5852 |

| CH3–sdef + CH3–adef″ | ν12 + ν14 | –0.4138 | |

| CH3–adef′ | 2ν13 | 0.2968 | |

| 2923 | CH3–adef″ | 2ν14 | –0.5771 |

| CH3–sstr | ν17 | –0.4987 | |

| CH3–adef′ | 2ν13 | –0.3752 | |

| 2931 | CH2–astr | ν18 | –0.5134 |

| CH3–adef′ + CH2–sdef | ν13 + ν15 | 0.4367 | |

| CH3–adef″ + CH2–sdef | ν14 + ν15 | 0.4249 | |

| 2950 | CH2–astr | ν18 | 0.5068 |

| CH2–sdef | 2ν15 | –0.4341 | |

| CH3–adef″ + CH2–sdef | ν14 + ν15 | 0.4097 | |

| 2959 | CH2–sdef | 2ν15 | –0.6244 |

| CH3–astr′ | ν19 | –0.4643 | |

| CH2–astr | ν18 | –0.4046 | |

| 2978 | CH3–astr″ | ν20 | 0.8087 |

| CH3–adef″ + CH2–sdef | ν14 + ν15 | 0.3754 | |

| CH3–astr′ | ν19 | –0.2759 | |

| 2979 | CH2–sdef | 2ν15 | 0.5336 |

| CH3–astr′ | ν19 | –0.5294 | |

| CH3–adef″ + CH2–sdef | ν14 + ν15 | 0.3885 | |

Figure 2.

Schematic of normal mode vectors of trans-ethanol.

The presence of mixed states, notably due to Fermi resonances, found with MULTIMODE are evidently not a “problem” for the AS SCIVR simulations. There are two aspects that make AS SCIVR efficient in this task. One is that calculations, trajectories and potential are full-dimensional and this allows one to take into account couplings between all modes. Second, the presence in eq 6 of coherent states, which have a Gaussian shape and therefore a tail in phase space, allows one to correctly collect quantum eigenenergies even if the energy of the trajectories is not perfectly tailored for the state under investigation. Interestingly, the VSCF/VCI energy of mode 16 of trans-ethanol, for which the mixing analysis was given above, differs by 70 and 77 cm–1 with respect to the AS SCIVR frequency and the experimental frequency, respectively. At this point the source of the difference is not clear. Hopefully, independent quantum calculations can be done to resolve this issue. Unfortunately, our computer resources preclude larger MULTIMODE calculations. Also, the Fermi resonances predicted in the MM and AS SCIVR calculations should result in spectral features that could be observed in high-resolution, ideally very cold, IR spectra. Unfortunately, the present experimental spectra77 are not high resolution and they are further complicated by the presence of both conformers.

Summary and Conclusions

A recently developed, full-dimensional CCSD(T) potential energy surface for ethanol has been employed to compute the anharmonic vibrational frequencies of both trans- and gauche-ethanol. We found good agreement between MULTIMODE and semiclassical AS SCIVR calculations as well as the previously reported experimental results as shown in Tables 1 and 2. In addition, we also observed significant mixing between the vibrational states and Fermi resonances when low-frequency bending modes are included during VCI calculations. Therefore combination of a precise PES and efficient quantum approximate approaches allows one to study accurately complex effects characterizing vibrational spectra. This work also demonstrates the possibility to perform very accurate quantum simulations when the high-energy region of the potential is adequately sampled. In fact, the AS SCIVR simulations require running classical trajectories at energies even higher than the zero-point one, and we found no issues employing the PES at such high energies.

We found mode 16 of trans-ethanol to be strongly mixed, and we got different estimates of the vibrational frequency from Multimode and AS SCIVR calculations. Additional quantum mechanical calculations and even higher resolution experimental spectra could help in clarifying the issue and calculations here presented could serve as benchmark.

A possible future development of this work consists in comparing VCI and SC intensities to the experiment. This will require construction of a dipole moment surface since one is currently not available for ethanol.

Another possible future development of this work concerns the study of the delocalization of excited states. This could be for instance tackled by calculating and examining semiclassical wave functions of the excited states.

Acknowledgments

J.M.B. thanks the ARO, DURIP grant (W911NF-14-1-0471), for funding a computer cluster where most of the calculations were performed and current financial support from NASA (80NSSC20K0360). R.C. thanks Università degli Studi di Milano (“PSR, Azione A Linea 2 - Fondi Giovani Ricercatori”) for support.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jpca.2c06322.

Zip archive containing all files needed to run the ethanol PES employed in this work (ZIP)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Special Issue

Published as part of The Journal of Physical Chemistry virtual special issue “Paul L. Houston Festschrift”.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bowman J. M.; Czakó G.; Fu B. High-dimensional ab initio potential energy surfaces for reaction dynamics calculations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 8094–8111. 10.1039/c0cp02722g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu C.; Yu Q.; Bowman J. M. Permutationally invariant potential energy surfaces. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2018, 69, 151–175. 10.1146/annurev-physchem-050317-021139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu B.; Zhang D. H. Ab initio potential energy surfaces and quantum dynamics for polyatomic bimolecular reactions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2018, 14, 2289–2303. 10.1021/acs.jctc.8b00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang B.; Li J.; Guo H. High-Fidelity Potential Energy Surfaces for Gas-Phase and Gas-Surface Scattering Processes from Machine Learning. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 5120–5131. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c00989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu C.; Bowman J. M. An ab initio potential energy surface for the formic acid dimer: Zero-point energy, selected anharmonic fundamental energies, and ground-state tunneling splitting calculated in relaxed 1–4-mode subspaces. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 24835–24840. 10.1039/C6CP03073D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp D.; Tajti V.; Györi T.; Czakó G. Theory Finally Agrees with Experiment for the Dynamics of the Cl + C2H6 Reaction. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 4762–4767. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c01263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y.-L.; Lu X.; Han Y.-C.; Fu B.; Zhang D. H.; Bowman J. M. Collision-induced and complex-mediated roaming dynamics in the H + C2H4 →H2 + C2H3 reaction. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 2148–2154. 10.1039/C9SC05951B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu D.; Behler J.; Li J. Accurate Global Potential Energy Surfaces for the H + CH3OH Reaction by Neural Network Fitting with Permutation Invariance. J. Phys. Chem. A 2020, 124, 5737–5745. 10.1021/acs.jpca.0c04182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu C.; Bowman J. M. A Fragmented, Permutationally Invariant Polynomial Approach for Potential Energy Surfaces of Large Molecules: Application to N-methyl acetamide. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 150, 141101. 10.1063/1.5092794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi A.; Qu C.; Bowman J. M. Full and Fragmented Permutationally Invariant Polynomial Potential Energy Surfaces for trans and cis N-methyl Acetamide and Isomerization Saddle Points. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 151, 084306. 10.1063/1.5119348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conte R.; Houston P. L.; Qu C.; Li J.; Bowman J. M. Full-dimensional, ab initio potential energy surface for glycine with characterization of stationary points and zero-point energy calculations by means of diffusion Monte Carlo and semiclassical dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 244301. 10.1063/5.0037175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston P. L.; Conte R.; Qu C.; Bowman J. M. Permutationally Invariant Polynomial Potential Energy Surfaces for Tropolone and H and D atom Tunneling Dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 024107. 10.1063/5.0011973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan S. J.; Yang Q. A Survey on Transfer Learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2010, 22, 1345–1359. 10.1109/TKDE.2009.191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. S.; Nebgen B. T.; Zubatyuk R.; Lubbers N.; Devereux C.; Barros K.; Tretiak S.; Isayev O.; Roitberg A. E. Approaching coupled cluster accuracy with a general-purpose neural network potential through transfer learning. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2903–2906. 10.1038/s41467-019-10827-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmiela S.; Sauceda H. E.; Müller K.-R.; Tkatchenko A. Towards exact molecular dynamics simulations with machine-learned force fields. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3887. 10.1038/s41467-018-06169-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauceda H. E.; Chmiela S.; Poltavsky I.; Müller K.-R.; Tkatchenko A. Molecular force fields with gradient-domain machine learning: Construction and application to dynamics of small molecules with coupled cluster forces. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 150, 114102. 10.1063/1.5078687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stöhr M.; Medrano Sandonas L.; Tkatchenko A. Accurate Many-Body Repulsive Potentials for Density-Functional Tight Binding from Deep Tensor Neural Networks. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 6835–6843. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c01307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Käser S.; Unke O.; Meuwly M. Reactive Dynamics and Spectroscopy of Hydrogen Transfer from Neural Network-Based Reactive Potential Energy Surfaces. New J. Phys. 2020, 22, 055002. 10.1088/1367-2630/ab81b5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan R.; Dral P. O.; Rupp M.; von Lilienfeld O. A. Big Data Meets Quantum Chemistry Approximations: The Δ-Machine Learning Approach. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 2087–2096. 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi A.; Qu C.; Houston P. L.; Conte R.; Bowman J. M. Δ-machine learning for potential energy surfaces: A PIP approach to bring a DFT-based PES to CCSD(T) level of theory. J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 154, 051102. 10.1063/5.0038301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu C.; Houston P. L.; Conte R.; Nandi A.; Bowman J. M. Breaking the Coupled Cluster Barrier for Machine-Learned Potentials of Large Molecules: The Case of 15-Atom Acetylacetone. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 4902–4909. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.1c01142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi A.; Conte R.; Qu C.; Houston P. L.; Yu Q.; Bowman J. M. Quantum Calculations on a New CCSD(T) Machine-Learned Potential Energy Surface Reveal the Leaky Nature of Gas-Phase Trans and Gauche Ethanol Conformers. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2022, 18, 5527–5538. 10.1021/acs.jctc.2c00760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarathy S. M.; Oßwald P.; Hansen N.; Kohse-Höinghaus K. Alcohol combustion chemistry. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2014, 44, 40–102. 10.1016/j.pecs.2014.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barraza-Botet C. L.; Wagnon S. W.; Wooldridge M. S. Combustion Chemistry of Ethanol: Ignition and Speciation Studies in a Rapid Compression Facility. J. Phys. Chem. A 2016, 120, 7408–7418. 10.1021/acs.jpca.6b06725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson P. G. Hydrogen bond studies. CXIII. The crystal structure of ethanol at 87 K. Acta Cryst. B 1976, 32, 232–235. 10.1107/S0567740876002653. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kakar R. K.; Quade C. R. Microwave rotational spectrum and internal rotation in gauche ethyl alcohol. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72, 4300–4307. 10.1063/1.439723. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.; Zhu W.; Lin K.; Hu N.; Yu Y.; Zhou X.; Yuan L.-F.; Hu S.-M.; Luo Y. Identification of Alcohol Conformers by Raman Spectra in the C–H Stretching Region. J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 3209–3217. 10.1021/jp513027r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston P. L.; Qu C.; Nandi A.; Conte R.; Yu Q.; Bowman J. M. Permutationally invariant polynomial regression for energies and gradients, using reverse differentiation, achieves orders of magnitude speed-up with high precision compared to other machine learning methods. J. Chem. Phys. 2022, 156, 044120. 10.1063/5.0080506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi A.; Qu C.; Bowman J. M. Using Gradients in Permutationally Invariant Polynomial Potential Fitting: A Demonstration for CH4 Using as Few as 100 Configurations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019, 15, 2826–2835. 10.1021/acs.jctc.9b00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MSA Software with Gradients, 2019. https://github.com/szquchen/MSA-2.0 (Accessed: 2019–01–20).

- Bowman J. M. Self-consistent Field Energies and Wavefunctions for Coupled Oscillators. J. Chem. Phys. 1978, 68, 608–610. 10.1063/1.435782. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman J. M. The Self-consistent-field Approach to Polyatomic Vibrations. Acc. Chem. Res. 1986, 19, 202–208. 10.1021/ar00127a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christoffel K.; Bowman J. Investigations of Self-consistent Field, SCF CI and Virtual state Configuration Interaction Vibrational Energies for a Model Three-mode System. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1982, 85, 220–224. 10.1016/0009-2614(82)80335-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter S.; Culik S. J.; Bowman J. M. Vibrational Self-consistent Field method for Many-mode Systems: A New Approach and Application to the Vibrations of CO Adsorbed on Cu(100). J. Chem. Phys. 1997, 107, 10458–10469. 10.1063/1.474210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter S.; Bowman J. M.; Handy N. C. Extensions and Tests of “Multimode”: A Code to Obtain Accurate Vibration/Rotation Energies of Many-Mode Molecules. Theor. Chem. Acc. 1998, 100, 191–198. 10.1007/s002140050379. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman J. M.; Carter S.; Huang X. MULTIMODE: a Code to Calculate Rovibrational Energies of Polyatomic Molecules. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2003, 22, 533–549. 10.1080/0144235031000124163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson J. K. G. Simplification of the Molecular Vibration-Rotation Hamiltonian. Mol. Phys. 1968, 15, 479–490. 10.1080/00268976800101381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski L.; Ziegler B.; Rauhut G. Tensor Decomposition in Potential Energy Surface Representations. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 145, 104103. 10.1063/1.4962368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler B.; Rauhut G. Efficient Generation of Sum-of-products Representations of High-dimensional Potential Energy Surfaces Based on Multimode Expansions. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 144, 114114. 10.1063/1.4943985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen O. Selected New Developments in Vibrational Structure Theory: Potential Construction and Vibrational Wave Function Calculations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 6672–6687. 10.1039/c2cp40090a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- König C.; Christiansen O. Automatic Determination of Important Mode-mode Correlations in Many-mode Vibrational Wave Functions. J. Chem. Phys. 2015, 142, 144115. 10.1063/1.4916518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder B.; Rauhut G. Incremental Vibrational Configuration Interaction Theory, iVCI: Implementation and Benchmark Calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 154, 124114. 10.1063/5.0045305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinu D. F.; Ziegler B.; Podewitz M.; Liedl K. R.; Loerting T.; Grothe H.; Rauhut G. The Interplay of VSCF/VCI Calculations and Matrix-isolation IR Spectroscopy - Mid Infrared Spectrum of CH3CH2F and CD3CD2F. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 2020, 367, 111224. 10.1016/j.jms.2019.111224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erfort S.; Tschöpe M.; Rauhut G. Toward a Fully Automated Calculation of Rovibrational Infrared Intensities for Semi-rigid Polyatomic Molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 244104. 10.1063/5.0011832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz G.; Artiukhin D. G.; Christiansen O. Approximate High Mode Coupling Potentials Using Gaussian Process Regression and Adaptive Density Guided Sampling. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 150, 131102. 10.1063/1.5092228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen N. K.; Jensen R. B.; Christiansen O. Calculating Vibrational Excitation Energies Using Tensor-decomposed Vibrational Coupled-cluster Response Theory. J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 154, 054113. 10.1063/5.0037240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moitra T.; Madsen D.; Christiansen O.; Coriani S. Vibrationally Resolved Coupled-cluster X-ray Absorption Spectra From Vibrational Configuration Interaction Anharmonic Calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 234111. 10.1063/5.0030202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman J. M.; Carrington T.; Meyer H.-D. Variational Quantum Approaches for Computing Vibrational Energies of Polyatomic Molecules. Mol. Phys. 2008, 106, 2145–2182. 10.1080/00268970802258609. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter S.; Bowman J. M.; Handy N. C. Multimode calculations of Rovibrational Energies of C2H4 and C2D4. Mol. Phys. 2012, 110, 775–781. 10.1080/00268976.2012.669504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter S.; Sharma A. R.; Bowman J. M. First-principles Calculations of Rovibrational Energies, Dipole Transition Intensities and Partition Function for Ethylene Using MULTIMODE. J. Chem. Phys. 2012, 137, 154301. 10.1063/1.4758005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy T. K.; Gerber R. B. Vibrational Self-consistent Field Calculations for Spectroscopy of Biological Molecules: New Algorithmic Developments and Applications. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 9468–9492. 10.1039/c3cp50739d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oschetzki D.; Rauhut G. Pushing the Limits in Accurate Vibrational Structure Calculations: Anharmonic Frequencies of Lithium Fluoride Clusters (LiF)n, n = 2–10. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 16426–16435. 10.1039/C4CP02264E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Császár A. G.; Fabri C.; Szidarovszky T.; Matyus E.; Furtenbacher T.; Czakó G. The Fourth Age of Quantum Chemistry: Molecules in Motion. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 1085–1106. 10.1039/C1CP21830A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennyson J. Perspective: Accurate Ro-vibrational Calculations on Small Molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 2016, 145, 120901. 10.1063/1.4962907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Carter S.; Bowman J. M. Pruning the Hamiltonian Matrix in MULTIMODE: Test for C2H4 and Application to CH3NO2 Using a New ab Initio Potential Energy Surface. J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 11632–11640. 10.1021/acs.jpca.5b09816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington T. Perspective: Computing (Ro-)vibrational Spectra of Molecules with More than Four Atoms. J. Chem. Phys. 2017, 146, 120902. 10.1063/1.4979117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner H.-J.; Knowles P. J.; Manby F. R.; Black J. A.; Doll K.; Heßelmann A.; Kats D.; Köhn A.; Korona T.; Kreplin D. A.; et al. The Molpro Quantum Chemistry Package. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 144107. 10.1063/5.0005081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman J. M.; Huang X.; Handy N. C.; Carter S. Vibrational Levels of Methanol Calculated by the Reaction Path Version of MULTIMODE, Using an ab Initio, Full-Dimensional Potential. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 7317–7321. 10.1021/jp070398m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conte R.; Parma L.; Aieta C.; Rognoni A.; Ceotto M. Improved semiclassical dynamics through adiabatic switching trajectory sampling. J. Chem. Phys. 2019, 151, 214107. 10.1063/1.5133144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botti G.; Ceotto M.; Conte R. On-the-fly adiabatically switched semiclassical initial value representation molecular dynamics for vibrational spectroscopy of biomolecules. J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 155, 234102. 10.1063/5.0075220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botti G.; Aieta C.; Conte R. The complex vibrational spectrum of proline explained through the adiabatically switched semiclassical initial value representation. J. Chem. Phys. 2022, 156, 164303. 10.1063/5.0089720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. H. The semiclassical initial value representation: A potentially practical way for adding quantum effects to classical molecular dynamics simulations. J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 2942–2955. 10.1021/jp003712k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huber D.; Heller E. J. Generalized Gaussian wave packet dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 1987, 87, 5302. 10.1063/1.453647. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kay K. G. Semiclassical propagation for multidimensional systems by an initial value method. J. Chem. Phys. 1994, 101, 2250–2260. 10.1063/1.467665. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann F. Semiclassical wave-packet propagation on potential surfaces coupled by ultrashort laser pulses. Phys. Rev. A 1999, 60, 1791. 10.1103/PhysRevA.60.1791. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak E.; Miret-Artés S. Thawed semiclassical IVR propagators. J. Phys. A 2004, 37, 9669. 10.1088/0305-4470/37/41/005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shalashilin D. V.; Child M. S. The phase space CCS approach to quantum and semiclassical molecular dynamics for high-dimensional systems. Chem. Phys. 2004, 304, 103–120. 10.1016/j.chemphys.2004.06.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aieta C.; Micciarelli M.; Bertaina G.; Ceotto M. Anharmonic quantum nuclear densities from full dimensional vibrational eigenfunctions with application to protonated glycine. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4384. 10.1038/s41467-020-18211-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aieta C.; Bertaina G.; Micciarelli M.; Ceotto M. Representing molecular ground and excited vibrational eigenstates with nuclear densities obtained from semiclassical initial value representation molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 153, 214117. 10.1063/5.0031391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begušić T.; Vaníček J. Finite-Temperature, Anharmonicity, and Duschinsky Effects on the Two-Dimensional Electronic Spectra from Ab Initio Thermo-Field Gaussian Wavepacket Dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12, 2997–3005. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.1c00123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q.; Bowman J. M.; Gazdy B. Application of adiabatic switching to vibrational energies of three-dimensional HCO, H2O, and H2CO. J. Chem. Phys. 1988, 89, 3124–3130. 10.1063/1.454969. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saini S.; Zakrzewski J.; Taylor H. S. Semiclassical quantization via adiabatic switching. II. Choice of tori and initial conditions for multidimensional systems. Phys. Rev. A 1988, 38, 3900–3908. 10.1103/PhysRevA.38.3900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy T.; Lendvay G. Adiabatic Switching Extended To Prepare Semiclassically Quantized Rotational-Vibrational Initial States for Quasiclassical Trajectory Calculations. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 4621–4626. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.7b01838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durig J.; Larsen R. Torsional vibrations and barriers to internal rotation for ethanol and 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol. J. Mol. Struct. 1990, 238, 195–222. 10.1016/0022-2860(90)85015-B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Veken B.; Coppens P. Conformer assignment of O-H stretches in ethanol and isopropanol. J. Mol. Struct. 1986, 142, 359–362. 10.101677/0022-2860(86)85133-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; Part of the special issue: Proceedings of the XVIIth European Congress on Molecular Spectroscopy.

- Katsyuba S. A.; Gerasimova T. P.; Spicher S.; Bohle F.; Grimme S. Computer-aided simulation of infrared spectra of ethanol conformations in gas, liquid and in CCl4 solution. J. Comput. Chem. 2022, 43, 279–288. 10.1002/jcc.26788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durig J. R.; Deeb H.; Darkhalil I. D.; Klaassen J. J.; Gounev T. K.; Ganguly A. The r0 structural parameters, conformational stability, barriers to internal rotation, and vibrational assignments for trans and gauche ethanol. J. Mol. Struct. 2011, 985, 202–210. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2010.10.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.