Abstract

Background

Adults previously infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) develop short-term immunity and may have increased reactogenicity to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines. This prospective, multicenter, active-surveillance cohort study examined the short-term safety of COVID-19 vaccines in adults with a prior history of SARS-CoV-2.

Methods

Canadian adults vaccinated between 22 December 2020 and 27 November 2021 were sent an electronic questionnaire 7 days post–dose 1, dose 2, and dose 3 vaccination. The main outcome was health events occurring in the first 7 days after each vaccination that prevented daily activities, resulted in work absenteeism, or required a medical consultation, including hospitalization.

Results

Among 684 998 vaccinated individuals, 2.6% (18 127/684 998) reported a prior history of SARS-CoV-2 infection a median of 4 (interquartile range: 2–6) months previously. After dose 1, individuals with moderate (bedridden) to severe (hospitalized) COVID-19 who received BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, or ChAdox1-S vaccines had higher odds of a health event preventing daily activities, resulting in work absenteeism or requiring medical consultation (adjusted odds ratio [95% confidence interval]: 3.96 [3.67–4.28] for BNT162b2, 5.01 [4.57–5.50] for mRNA-1273, and 1.84 [1.54–2.20] for ChAdox1-S compared with no infection). Following dose 2 and 3, the greater risk associated with previous infection was also present but was attenuated compared with dose 1. For all doses, the association was lower or absent after mild or asymptomatic infection.

Conclusions

Adults with moderate or severe previous SARS-CoV-2 infection were more likely to have a health event sufficient to impact routine activities or require medical assessment in the week following each vaccine dose.

Keywords: COVID-19 vaccines, adverse events following immunization, vaccine safety monitoring

In the week following receipt of a COVID-19 vaccine, individuals previously infected with SARS-CoV-2 were more likely to have a health event impacting routine activities or requiring medical assessment than those not previously infected.

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic has been associated with more than 6 million deaths globally as of July 2022 [1]. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines are essential tools to protect individuals against infection and to reduce the risk of severe disease. Although SARS-CoV-2 infection induces some natural immunity against subsequent SARS-CoV-2 infection [2, 3], immunity will attenuate over time and reinfection occurs among previously infected individuals [4, 5]. Thus, COVID-19 vaccination is important to broaden and maintain protection against serious illness for all variants of COVID-19 [6].

Recent evidence has shown that people with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection develop a more robust immune response, even after a single vaccine dose, compared with vaccinated infection-naive individuals [7–10]. This stronger antibody response to COVID-19 vaccines has led to concerns that vaccination of COVID-19–recovered individuals may result in a higher incidence of adverse events following immunization (AEFI). However, pre-licensure trials of COVID-19 vaccines did not systematically examine individuals with a previous SARS-CoV-2 infection [11, 12].

Data have been accumulating on the safety of COVID-19 vaccines in people with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. Early studies suggested that previous SARS-CoV-2 infection was associated with increased risk of AEFI (local as well as systemic) following mRNA or viral vector vaccines [13–17]. However, these studies were primarily descriptive and consisted of small samples with variable intervals after COVID-19 vaccination.

The Canadian National Vaccine Safety (CANVAS) network has conducted active vaccine safety surveillance in Canada since 2010 [18–21], initially for influenza vaccines and now adapted to monitor COVID-19 vaccine safety (CANVAS-COVID) [22]. The objective of this study was to profile common AEFI within 7 days after the first, second, and third doses of COVID-19 vaccine in participants with and without SARS-CoV-2 infection and to determine whether previous SARS-CoV-2 infection was associated with increased risk of health events resulting in medical attention.

METHODS

A prospective cohort of vaccinated participants were recruited from 7 Canadian provinces and territories (Ontario, Quebec, British Columbia, Alberta, Nova Scotia, Yukon, and Prince Edward Island) in which more than 75% of the Canadian population reside. Participants were enrolled after dose 1 and followed through their dose 2 vaccination. A separate sample of participants from Quebec were enrolled after dose 3. Eligibility criteria included receipt of a COVID-19 vaccine in the previous 7 days, ability to understand the study request in English or French, and access to e-mail and telephone. Study procedures are described in brief below, with a full description of the study methodology previously published [22].

All participants provided informed consent electronically. The Research Ethics Board at each participating site approved the study.

Survey Procedures

Date of vaccination was collected in 2 ways: electronically transferred from the vaccination registry or entered by the participants from their vaccine record. Eight days after vaccination with each dose, participants received an e-mail link to an online questionnaire that requested information about health events occurring in the previous 7 days. Nonresponders were sent 2 reminder e-mails.

Medically attended events triggered a telephone call from a research assistant or nurse trained in eliciting AEFI information.

Description of Questionnaires and Outcomes

The online questionnaire collected information on demographics (ie, age group, sex), health status (adapted from the Canadian Community Health Survey [23] and the Clinical Frailty Scale [24]), and occurrence of health events of interest [22]. Ethnicity was captured on the dose 2 and dose 3 surveys. Participants rated their health status as excellent/good, fair, and poor/very poor. Vaccine products received were the BNT162b2 (Pfizer–BioNTech), mRNA-1273 (Moderna), and ChAdOx1-S (AstraZeneca) vaccines. The main outcome was health events occurring within 7 days of vaccination that prevented daily activities, resulted in work or school absenteeism, and/or required a medical consultation, including hospitalization. The secondary outcome was a “serious health event” defined as a health event resulting in an emergency department visit and/or hospitalization in the previous 7 days. All participants were asked whether they had injection-site reactions. Other events of interest were asked only to those with the main outcome. If participants reported the main outcome they were then asked to select the symptoms they experienced from a list. An “other” category with a text field was provided for symptoms not included in the list. Self-reported, prior laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, with the date of positive test, if known, was captured. Participants determined the severity of their SARS-CoV-2 infection based on the following survey definitions: asymptomatic (no symptoms), mild (prevented some normal daily activities), moderate (prevented all normal daily activities [bedridden]), and severe (hospitalized).

Statistical Analysis

For the dose 1 and dose 2 analysis, we included vaccinated study participants who received at least their first dose of vaccine from 22 December 2020–27 November 2021 and answered the question about any previous laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. Dose 3 analysis included Quebec participants who received their third dose of vaccine from 22 January 2022 to 20 February 2022.

Frequencies and proportions were calculated for primary and secondary outcomes in participants with and without previous SARS-CoV-2 infection after each dose of vaccine for each of the 3 vaccine products. Participants whose dose 2 was a different vaccine product than their dose 1 were classified as mixed-schedule recipients at dose 2. Multivariable logistic regression was used to determine whether previous SARS-CoV-2 infection increased the risk of AEFI for each vaccine product after each dose after controlling for age, sex, health status, and (for dose 2 estimates only) experience of a health event in dose 1. Previous infection was dichotomized as yes or no at each dose, but once an individual had an infection they were not included in the uninfected group for any subsequent analyses. For example, individuals who were infected between dose 1 and 2 were included in the uninfected group for the dose 1 analysis and then in the infected group for the dose 2 analyses. Those who were infected prior to dose 1 were in the infected group for all analyses. Estimates with 95% Wald confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Estimates were considered significant when the 95% CI did not cross 1. Data cleaning was conducted in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc), and analysis was completed using R software version 4.1.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

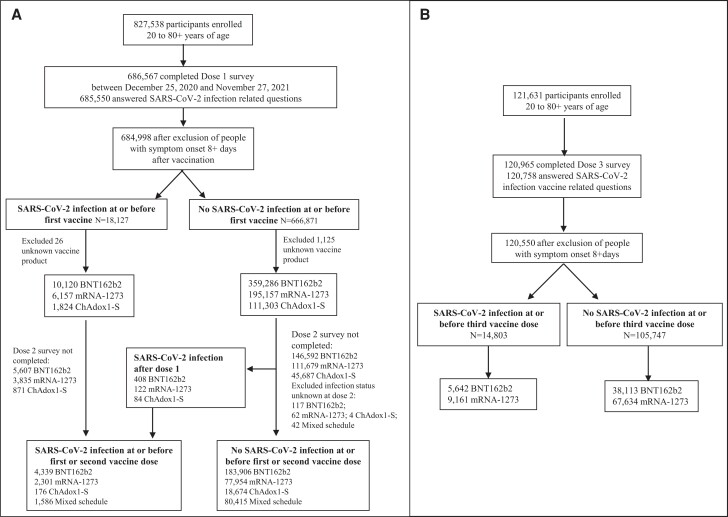

As of 27 November 2021, 684 998 vaccinated participants had completed their dose 1 survey and met the eligibility criteria for this analysis: 369 406, 201 314, and 113 127 received BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, and ChAdox1-S, respectively (Figure 1A ). As of 20 February 2022, 120 758 vaccinated participants had completed their third booster-dose survey and met the eligibility criteria for this analysis: 43 755 received BNT162b2 and 76 795 received mRNA-1273 (Figure 1B ).

Figure 1.

A, Previous SARS-CoV-2 infection analytic sample for CANVAS-COVID adult participants, dose 1 and dose 2. B, Previous SARS-CoV-2 infection analytic sample for CANVAS-COVID adult participants, booster/third dose. Abbreviations: CANVAS-COVID, Canadian National Vaccine Safety network adapted to monitor coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine safety; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Overall, 18 127 (2.6%) participants reported previous laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection a median of 4 months prior to dose 1 vaccination. Participant details by SARS-CoV-2 infection status and vaccine type at dose 1 are shown in Table 1. An overall median of 2 months elapsed between the first and second vaccine dose (Table 2). The interval between dose 2 and 3 was not captured, but the national recommendation was for at least a 6-month interval between the primary series and first booster dose [25].

Table 1.

Dose 1–Vaccinated Participant Characteristics With and Without Previous SARS-CoV-2 Infection

| BNT162b2 | mRNA-1273 | ChAdox1-S | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 (−) | SARS-CoV-2 (+) | SARS-CoV-2 (−) | SARS-CoV-2 (+) | SARS-CoV-2 (−) | SARS-CoV-2 (+) | |

| Sample, n | 359 286 | 10 120 | 195 157 | 6157 | 111 303 | 1824 |

| Health event prevented daily activities or required medical care | 12 176 (3.39) | 1215 (12.01) | 8184 (4.19) | 1001 (16.26) | 12 805 (11.50) | 250 (13.71) |

| Medically attended event | 3560 (0.99) | 293 (2.90) | 2379(1.22) | 171(2.78) | 1589 (1.43) | 45(2.47) |

| Serious health event | 859 (0.24) | 70 (0.69) | 566 (0.29) | 42 (0.68) | 508 (0.46) | 10 (0.55) |

| ȃEmergency department visit | 829 (0.23) | 65 (0.64) | 550 (0.28) | 39 (0.63) | 493 (0.44) | 10 (0.55) |

| ȃHospitalization | 30 (0.01) | 5 (0.05) | 16 (0.01) | 3 (0.05) | 15 (0.01) | 0 |

| Age groups | ||||||

| ȃ20–29 years | 43 093 (11.99) | 2511 (24.81) | 25 619 (13.13) | 1238 (20.11) | 262 (0.24) | 27 (1.48) |

| ȃ30–39 years | 57 276 (15.94) | 2532 (25.02) | 48 691 (24.95) | 1663 (27.01) | 1283 (1.15) | 48 (2.63) |

| ȃ40–49 years | 43 720 (12.17) | 1991 (19.67) | 36 864 (18.89) | 1291 (20.97) | 20 809 (18.70) | 392 (21.49) |

| ȃ50–64 years | 71 107 (19.79) | 1653 (16.33) | 55 599 (28.49) | 1567 (24.45) | 79 324 (71.27) | 1274 (69.85) |

| ȃ65–79 years | 123 940 (34.50) | 1262 (12.47) | 25 844 (13.24) | 369 (5.99) | 9272 (8.33) | 80 (4.39) |

| ȃ80+ years | 20 150 (5.61) | 171 (1.69) | 2540 (1.3) | 29 (0.47) | 353(0.32) | 3 (0.16) |

| Sex | ||||||

| ȃMale | 143 773 (40.01) | 3795 (37.5) | 82 814 (42.43) | 2638 (42.85) | 57 134 (51.33) | 990 (54.28) |

| ȃFemale | 214 813 (59.79) | 6310 (62.35) | 111 976 (57.38) | 3517 (57.12) | 54 079(48.59) | 833 (45.67) |

| ȃDecline/intersex | 700 (0.20) | 15 (0.15) | 367 (0.18) | 2(0.03) | 90 (0.08) | 1 (0.05) |

| Health status | ||||||

| ȃExcellent/good | 308 952 (85.99) | 8586 (84.84) | 173 051 (88.92) | 5475 (88.92) | 101 321 (91.03) | 1650 (90.46) |

| ȃFair | 22 719 (6.32) | 442 (4.37) | 10 887 (5.58) | 253 (4.11) | 4094 (3.68) | 70 (3.84) |

| ȃPoor | 4401 (1.22) | 80 (0.79) | 1791 (0.92) | 40 (0.65) | 489 (0.44)) | 6 (0.33) |

| ȃUnknown | 23 214 (6.46) | 1012 (10.00) | 9428 (4.83) | 389 (6.32) | 5399 (4.85) | 98 (5.37) |

| COVID-19 severity | ||||||

| ȃMild/asymptomatic | … | 6395 (63.19) | … | 3849 (62.52) | … | 1164 (63.82) |

| ȃModerate/severe | … | 3721 (36.81) | … | 2307 (37.47) | … | 660 (36.18) |

| Median (IQR) intervala between SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination, months | … | 4 (2–6) | … | 5 (3–6) | … | 4 (3–6) |

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; IQR, interquartile range; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; –, never infected; +, previously infected.

Only participants who provided a date of infection were included in the interval calculation.

Table 2.

Dose 2–Vaccinated Participant Characteristics With and Without Previous SARS-CoV-2 Infection

| BNT162b2 | mRNA-1273 | ChAdox1-S | Mixed Schedule | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 (−) | SARS-CoV-2 (+) | SARS-CoV-2 (−) | SARS-CoV-2 (+) | SARS-CoV-2 (−) |

SARS-CoV-2 (+) | SARS-CoV-2 (−) | SARS-CoV-2 (+) | |

| Sample, n | 183 906 | 4339 | 77 954 | 2301 | 18 674 | 176 | 80 415 | 1586 |

| Health event prevented daily activities or required medical care | 7554 (4.11) | 350 (8.07) | 8557 (10.98) | 298 (12.95) | 295 (1.58) | 5 (2.84) | 6461 (8.03) | 185 (11.66) |

| Medically attended event | 1833 (1.00) | 77 (1.77) | 1110 (1.42) | 48 (2.09) | 103 (0.55) | 3 (1.7) | 782 (0.97) | 20 (1.26) |

| Serious health event | 426 (0.23) | 23 (0.53) | 237 (0.30) | 10 (0.43) | 31 (0.17) | 1 (0.57) | 191 (0.24) | 4 (0.25) |

| Emergency department visit | 404 (0.22) | 21 (0.48) | 224 (0.29) | 10 (0.43) | 31 (0.17) | 1 (0.57) | 184 (0.23) | 4 (0.25) |

| Hospitalization | 22 (0.01) | 2 (0.05) | 13 (0.02) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 (0.01) | 0 |

| Age groups | ||||||||

| 20–29 years | 16 484 (8.96) | 835 (19.24) | 9521 (12.21) | 385 (16.73) | 14 (0.07) | 3 (1.70) | 3969 (4.94) | 138 (8.7 |

| 30–39 years | 26 458 (14.39) | 1092 (25.17) | 19 952 (25.59) | 654 (28.42) | 109 (0.58) | 2 (1.14) | 6800 (8.46) | 205 (12.93) |

| 40–49 years | 21 152 (11.5) | 846 (19.5) | 13 169 (16.89) | 478 (20.77) | 1150 (6.16) | 17 (9.66) | 13 817 (17.18) | 285 (17.97) |

| 50–64 years | 39 801 (21.64) | 875 (20.17) | 21 852 (28.03) | 606 (26.34) | 14 319 (76.68) | 140 (79.55) | 42 265 (52.56) | 793 (50.00 |

| 65–79 years | 69 162 (37.61) | 613 (14.13) | 12 355 (15.85) | 165 (7.17) | 2975 (15.93) | 14 (7.95) | 12 818 (15.94) | 156 (9.84) |

| 80+ years | 10 849 (5.9) | 78 (1.8) | 1105 (1.42) | 13 (0.56) | 107 (0.57) | 0 | 746 (0.93) | 9 (0.57) |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 70 530 (38.35) | 1497 (34.50) | 31 293 (40.14) | 907 (39.42) | 9270 (49.64) | 105 (59.66) | 35 867 (44.60) | 741 (46.72) |

| Female | 113 137 (61.52) | 2838 (65.41) | 46 553 (59.72) | 1394 (60.58) | 9383 (50.25) | 71 (40.34) | 44 481 (55.31) | 844 (53.22) |

| Decline/intersex | 239 (0.13) | 4 (0.09) | 108(0.14) | 0 | 21 (0.12) | 0 | 67 (0.08) | 1 (0.06) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Black | 1383 (0.75) | 82 (1.89) | 890 (1.14) | 45 (1.96) | 52 (0.28) | 0 | 469 (0.58) | 26 (1.64) |

| Asian | 5196 (2.83) | 75 (1.73) | 2356 (3.02) | 45 (1.96) | 86 (0.46) | 1 (0.57) | 1434 (1.78) | 11 (0.69) |

| Indigenous | 950 (0.52) | 36 (0.83) | 534 (0.69) | 27 (1.17) | 29 (0.16) | 0 | 328 (0.41) | 5 (0.32) |

| Latino | 1331 (0.72) | 78 (1.8) | 1273 (1.63) | 79 (3.43) | 93 (0.5) | 3 (1.7) | 625 (0.78) | 30 (1.89) |

| Arabic | 1747 (0.95) | 112 (2.58) | 1329 (1.7) | 74 (3.22) | 70 (0.37) | 3 (1.7) | 511 (0.64) | 25 (1.58) |

| Indian/Pakistani | 3587 (1.95) | 223 (5.14) | 1147 (1.47) | 64 (2.78) | 74 (0.4) | 1 (0.57) | 1048 (1.3) | 44 (2.77) |

| South East Asian | 1870 (1.02) | 111 (2.56) | 866 (1.11) | 36 (1.56) | 53 (0.28) | 0 | 543 (0.68) | 24 (1.51) |

| White | 97 691 (53.12) | 2213 (51) | 51 368 (65.9) | 1448 (62.93) | 8220 (44.02) | 100 (56.82) | 53 547 (66.59) | 1039 (65.51) |

| Mixed | 2526 (1.37) | 116 (2.67) | 1515 (1.94) | 55 (2.39) | 126 (0.67) | 1 (0.57) | 1124 (1.4) | 28 (1.77) |

| Other/unknown | 64 735 (35.2) | 1236 (28.49) | 16 223 (20.81) | 421 (18.3) | 9191 (49.22) | 62 (35.23) | 20 047 (24.93) | 347 (21.88) |

| Declined | 2890 (1.57) | 57 (1.31) | 453 (0.58) | 7 (0.3) | 680 (3.64) | 5 (2.84) | 739 (0.92) | 7 (0.44) |

| Health status | ||||||||

| Excellent/good | 159 271 (86.6) | 3610 (83.2) | 68 334 (87.66) | 2018 (87.7) | 17 532 (93.88) | 157 (89.2) | 72 381 (90.01) | 1397 (88.08) |

| Fair | 10 233 (5.56) | 172 (3.96) | 3900 (5) | 95 (4.13) | 626 (3.35) | 8 (4.55) | 3406 (4.24) | 65 (4.1) |

| Poor | 1972 (1.07) | 29 (0.67) | 584 (0.75) | 8 (0.35) | 75 (0.4) | 0 | 463 (0.58) | 8 (0.5) |

| Declined | 12 430 (6.76) | 528 (12.17) | 5136 (6.59) | 180 (7.82) | 441 (2.36) | 11 (6.25) | 4165 (5.18) | 116 (7.31) |

| COVID-19 severity | ||||||||

| Mild/asymptomatic | … | 2820 (64.99) | … | 1476 (64.15) | … | 109 (61.93) | … | 1049 (66.14) |

| Moderate/severe | … | 1518 (35.01) | … | 825 (35.85) | … | 67 (38.07) | … | 537 (33.86) |

| Median (IQR) interval between doses, months | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–2) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–2) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) |

| Median (IQR) intervala between SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination, months | … | 6 (3–8) | … | 7 (4–9) | … | 6 (4–9) | … | 6 (4–9) |

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; IQR, interquartile range; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; –, never infected; +, previously infected.

Only participants who provided a date of infection were included in the interval calculation.

Health Events Following Vaccination

In the week following dose 1 vaccination, a higher percentage of participants with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection had events of sufficient severity to prevent daily activities, result in work or school absenteeism, or require a medical consultation (main outcome) for all 3 vaccine types (12% to 16% for previously infected vs 3% to 12% for noninfected) (Table 1). Additionally, a higher percentage of previously infected participants reported serious AEFI (emergency room or hospitalization; 0.6% to 0.7% previously infected vs 0.2% to 0.5% noninfected) (Table 1).

In the week following dose 2 vaccination, results were similar, with a higher percentage of participants with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection reporting events of sufficient severity to prevent daily activities, result in work or school absenteeism, or require a medical consultation (main outcome) for all 3 vaccine types and for the mixed schedules (Table 2).

In the week following dose 3 vaccination with either BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273, a higher proportion of previously infected participants reported events of sufficient severity to prevent daily activities, result in work or school absenteeism, or require a medical consultation than those not infected (Table 3).

Table 3.

Booster Dose 3–Vaccinated Participant Characteristics With and Without Previous SARS-CoV-2 Infection

| BNT162b2 | mRNA-1273 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 (−) |

SARS-CoV-2 (+) |

SARS-CoV-2 (−) |

SARS-CoV-2 (+) |

|

| Sample, n | 38 113 | 5642 | 67 634 | 9161 |

| Health event prevented daily activities or required medical care | 1853 (4.86) | 374 (6.63) | 3819 (5.65) | 769 (8.39) |

| Medically attended event | 514 (1.35) | 75 (1.33) | 743 (1.1) | 110 (1.2) |

| Serious health event | 113 (0.30) | 26 (0.46) | 134 (0.2) | 25 (0.27) |

| Emergency department visit | 105 (0.28) | 24 (0.43) | 127 (0.19) | 19 (0.21) |

| Hospitalization | 8 (0.02) | 2 (0.04) | 7 (0.01) | 6 (0.07) |

| Age groups | ||||

| 20–29 years | 15 220 (39.93) | 1973 (34.97) | 1860 (2.75) | 265 (2.89) |

| 30–39 years | 6700 (17.58) | 1013 (17.95) | 15 335 (22.67) | 2155 (23.52) |

| 40–49 years | 6352 (16.67) | 1097 (19.44) | 16 435 (24.3) | 2501 (27.3) |

| 50–64 years | 7434 (19.51) | 1174 (20.81) | 23 951 (35.41) | 3162 (34.52) |

| 65–79 years | 2096 (5.5) | 357 (6.33) | 8837 (13.07) | 992 (10.83) |

| 80+ years | 311 (0.82) | 28 (0.5) | 1216 (1.8) | 86 (0.94) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 15 963 (41.88) | 2246 (39.81) | 31 086 (45.96) | 4046 (44.17) |

| Female | 22 054 (57.86) | 3391 (60.1) | 36 432 (53.87) | 5107 (55.75) |

| Decline/intersex | 96 (0.25) | 5 (0.09) | 116 (0.18) | 8 (0.08) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Black | 525 (1.38) | 79 (1.4) | 766 (1.13) | 105 (1.15) |

| Asian | 771 (2.02) | 56 (0.99) | 652 (0.96) | 37 (0.4) |

| Indigenous | 231 (0.61) | 46 (0.82) | 418 (0.62) | 68 (0.74) |

| Latino | 921 (2.42) | 226 (4.01) | 1331 (1.97) | 273 (2.98) |

| Arabic | 815 (2.14) | 162 (2.87) | 872 (1.29) | 133 (1.45) |

| Indian/Pakistani | 395 (1.04) | 48 (0.85) | 301 (0.45) | 54 (0.59) |

| South East Asian | 432 (1.13) | 82 (1.45) | 408 (0.6) | 69 (0.75) |

| White | 29 109 (76.38) | 4249 (75.31) | 53 785 (79.52) | 7146 (78) |

| Mixed | 829 (2.18) | 107 (1.9) | 790 (1.17) | 100 (1.09) |

| Other/unknown | 4085 (10.72) | 587 (10.4) | 8310 (12.29) | 1176 (12.84) |

| Health status | ||||

| Excellent/good | 35 928 (94.27) | 5348 (94.79) | 62 850 (92.93) | 8681 (94.76) |

| Fair | 1637 (4.3) | 217 (3.85) | 3564 (5.27) | 370 (4.04) |

| Poor | 268 (0.7) | 29 (0.51) | 697 (1.03) | 54 (0.59) |

| Unknown | 280 (0.73) | 48 (0.85) | 523 (0.77) | 56 (0.61) |

| COVID-19 severity | ||||

| Mild/asymptomatic | … | 4238 (75.15) | … | 6870 (75.02) |

| Moderate/severe | … | 1402 (24.85) | … | 2288 (24.98) |

| Median (IQR) intervala between SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination, months | … | 2 (1–9) | … | 2 (1–8) |

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; IQR, interquartile range; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; –, never infected; +, previously infected.

Only participants who provided a date of infection were included in the interval calculation.

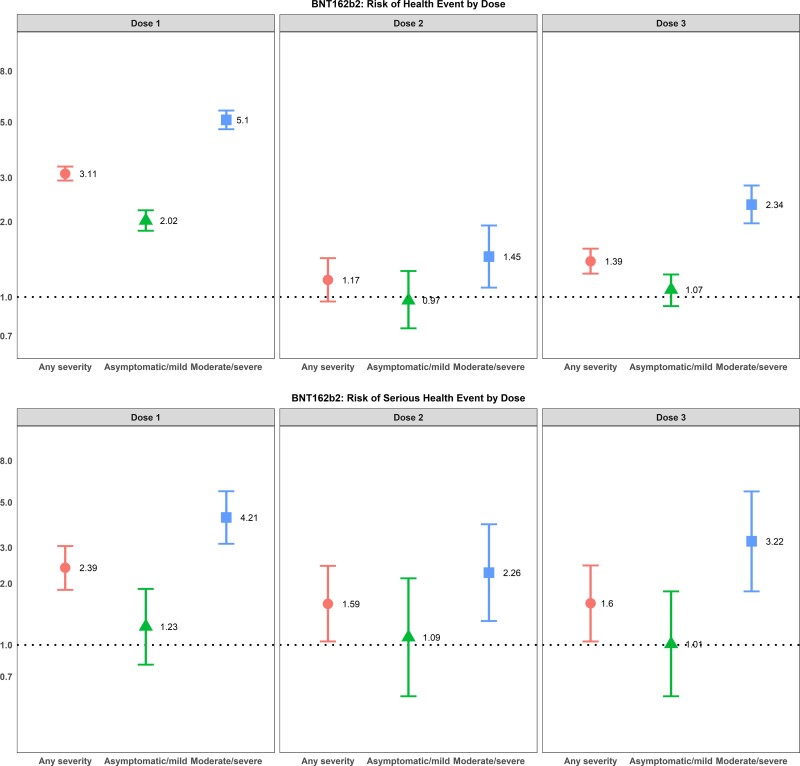

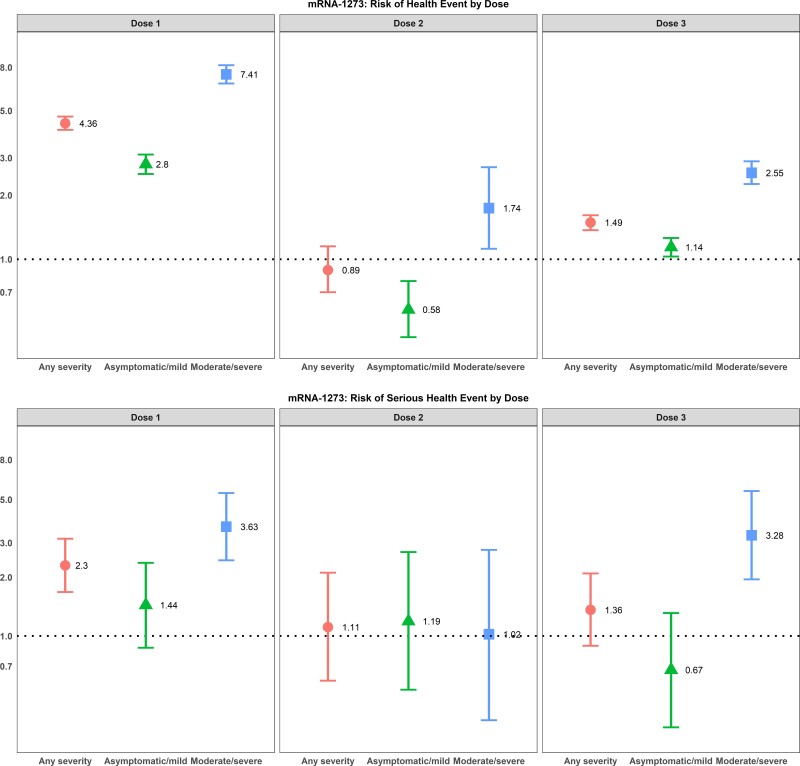

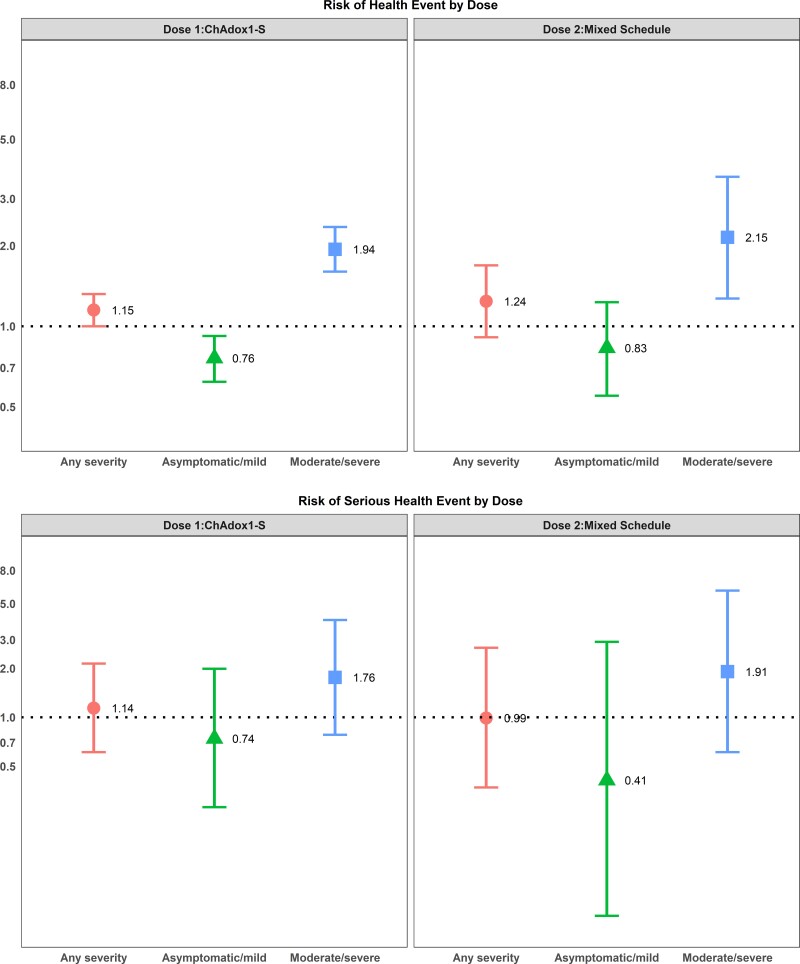

After adjusting for age, sex, and health status, individuals with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection of any severity who were vaccinated with either of the mRNA vaccines had a higher odds of reporting events of sufficient severity to prevent daily activities or result in work absenteeism or require a medical consultation after their first dose, whereas only individuals with a moderate/severe SARS-CoV-2 infection had higher odds of a health event after their first dose of ChAdox1-S vaccine (Figures 2–4). For mRNA vaccine recipients, moderate/severe infection was also associated with an increased odds of emergency department visits or hospitalizations (serious AEFI) in the week following dose 1 vaccination while asymptomatic/mild infections were not (Figures 2–4). For ChAdox1-S vaccine recipients at dose 1, previous infection was not associated with an increased probability of emergency department visits or hospitalizations (serious AEFI).

Figure 2.

Multivariable logistic regression for the association between previous SARS-CoV-2 infection and severity of previous COVID-19 disease and (1) development of events of sufficient severity to prevent daily activities or result in work or school absenteeism and/or require a medical consultation (top panels) and (2) events requiring an emergency department visit or hospitalization (serious health events) (bottom panels) within 7 days after dose 1, dose 2, and dose 3 vaccination with BNT162b2. Note: 95% CIs >1 indicate that health events are more likely to occur in individuals with a previous SARS-CoV-2 infection; 95% CIs <1 indicate that events are less likely to occur in individuals with a previous SARS-CoV-2 infection; 95% CIs that cross 1 indicate no association between health-event incidence and previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. The reference group is participants with no previous SARS-COV-2 infection. Odds ratios are adjusted for age group, sex, health status, and province. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Figure 3.

Multivariable logistic regression for the association between previous SARS-CoV-2 infection and severity of previous COVID-19 disease and (1) development of events of sufficient severity to prevent daily activities or result in work or school absenteeism and/or require a medical consultation (top panels) and (2) events requiring emergency department visit or hospitalization (serious health events) (bottom panels) within 7 days after dose 1, dose 2, and dose 3 vaccination with mRNA-1273. Note: 95% CIs >1 indicate that health events are more likely to occur in individuals with a previous SARS-CoV-2 infection; 95% CIs <1 indicate that events are less likely to occur in individuals with a previous SARS-CoV-2 infection; 95% CIs that cross 1 indicate no association between health-event incidence and previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. The reference group is participants with no previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. Odds ratios are adjusted for age group, sex, health status, province, and experience of health event in dose 1. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Figure 4.

Multivariable logistic regression for the association between previous SARS-CoV-2 and severity of previous COVID-19 disease and (1) development of events of sufficient severity to prevent daily activities or result in work or school absenteeism and/or require a medical consultation (top panels) and (2) events requiring emergency department visit or hospitalization (serious health events) (bottom panels) within 7 days after dose 1 with ChAdox1-S vaccine and dose 2 mixed schedule. Note: Data from Quebec province only. 95% CIs >1 indicate that health events are more likely to occur in individuals with a previous SARS-CoV-2 infection; 95% CIs <1 indicate that events are less likely to occur in individuals with a previous SARS-CoV-2 infection; 95% CIs that cross 1 indicate no association between health-event incidence and previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. The reference group is participants with no previous SARS-CoV-2 infection. Odds ratios are adjusted for age group, sex, and health status. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Following dose 2, the relationship between previous infection and AEFI was attenuated compared with dose 1 after adjusting for age, sex, and health status. Individuals with asymptomatic or mild infections did not have an increased risk of health events following their second dose, for either mRNA vaccine product and for a heterologous vaccine schedule (eg, ChAdox1-S followed by either mRNA vaccine or 1 mRNA vaccine followed by a different mRNA vaccine product). The risk of health events was still slightly elevated for those with moderate to severe previous infections (Figures 2–4). The risk could not be calculated for recipients of the ChAdox1-S vaccine as too few people who were previously infected received a homologous vaccine schedule with this product. For serious events following mRNA vaccines, although the number of serious events in previously infected, 2-dose vaccine recipients was small, the risk was still increased for BNT162b2 vaccine recipients with a moderate or severe previous infection compared with those without an infection. However, the effect was also attenuated compared with the first dose (Figures 2–4).

Following dose 3 vaccination, the relationship between previous infection and AEFI was similar to dose 1 after adjusting for age, sex, and health status, but with smaller effect sizes compared with the first dose (Figures 2–4).

Frequency of Specific Health Events Following Vaccination

Injection-site reactions were solicited for all participants and occurred significantly more frequently among participants with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection for all vaccine products after dose 1 (Table 4), while they only occurred significantly more frequently in previously infected participants who received BNT162b2 and ChAdox1-S after dose 2 (Table 5). A significantly higher proportion of previously infected participants who received mRNA-1273 for their third dose reported injection-site reactions, while rates were similar for BNT162b2 recipients (Table 6).

Table 4.

Health Events Reported That Prevented Daily Activities or Resulted in Work or School Absenteeism and/or Required a Medical Consultation Within 7 Days After Dose 1 Vaccination, Among Vaccinated Participants With and Without SARS-CoV-2 Infection

| BNT162b2 | mRNA-1273 | ChAdox1-S | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 (−) | SARS-CoV-2 (+) | SARS-CoV-2 (−) | SARS-CoV-2 (+) | SARS-CoV-2 (−) | SARS-CoV-2 (+) | |

| Sample, n | 359 286 | 10 120 | 195 157 | 6157 | 111 303 | 1824 |

| Injection-site reactionsa | 174 083 (48.45) (95% CI: 48.30–48.60) |

6122 (60.49) (95% CI: 59.50–61.4) |

121 420 (62.22) (95% CI: 62.0–62.40) |

4013 (65.18) (95% CI: 64.0–66.40) |

48 900 (43.93) (95% CI: 43.60–44.20) |

935 (51.26) (95% CI: 49.00–53.50) |

| General | ||||||

| Unwell/malaise/myalgia/fatigue | 9954 (2.77) | 1120 (11.07) | 6931 (3.55) | 956 (15.53) | 12 252 (11.01) | 242 (13.27) |

| Fever (≥38°C) | 1698 (0.47) | 439 (4.34) | 1603 (0.82) | 526 (8.54) | 5836 (5.24) | 117 (6.41) |

| Arthritis/joint pain | 3892 (1.08) | 461 (4.56) | 2751 (1.41) | 427 (6.94) | 4868 (4.37) | 107 (5.87) |

| Nausea/vomiting/diarrhea | 5045 (1.40) | 514 (5.08) | 3232 (1.66) | 423 (6.87) | 4540 (4.08) | 96 (5.26) |

| Earache | 845 (0.24) | 89 (0.88) | 554 (0.28) | 69 (1.12) | 604 (0.54) | 8 (0.44) |

| Change in menstruation | 143 (0.07) | 8 (0.13) | 103 (0.09) | 4 (0.11) | 27 (0.05) | 0 |

| Jaundice | 22 (0.01) | 4 (0.04) | 20 (0.01) | 3 (0.05) | 4 (0) | 3 (0.16) |

| Neurologic | ||||||

| Headache/ migraine | 7060 (1.97) | 868 (8.58) | 4896 (2.51) | 754 (12.25) | 9330 (8.38) | 188 (10.31) |

| Dizziness/vertigo | 3199 (0.89) | 319 (3.15) | 2098 (1.08) | 244 (3.96) | 2685 (2.41) | 59 (3.23) |

| Paresthesia | 1427 (0.4) | 118 (1.17) | 982 (0.50) | 102 (1.66) | 1047 (0.94) | 17 (0.93) |

| Fainting | 191 (0.05) | 18 (0.18) | 130 (0.07) | 17 (0.28) | 83 (0.07) | 1 (0.05) |

| Inability to walk | 536 (0.15) | 66 (0.65) | 377 (0.19) | 73 (1.19) | 403 (0.36) | 10 (0.55) |

| Loss of taste/smell | 313 (0.09) | 125 (1.24) | 223 (0.11) | 77 (1.25) | 174 (0.16) | 20 (1.10) |

| Loss of vision | 175 (0.05) | 26 (0.26) | 143 (0.07) | 11 (0.18) | 88 (0.08) | 3 (0.16) |

| Sudden unilateral facial weakness/ paralysis | 119 (0.03) | 16 (0.16) | 101 (0.05) | 6 (0.1) | 60 (0.05) | 4 (0.22) |

| Seizure/ convulsion | 33 (0.01) | 2 (0.02) | 24 (0.01) | 4 (0.06) | 27 (0.02) | 0 |

| Other neurologicb | 467 (0.13) | 44 (0.43) | 326 (0.17) | 39 (0.63) | 200 (0.18) | 2 (0.11) |

| Infection | ||||||

| Urinary tract infection | 365 (0.1) | 37 (0.37) | 199 (0.1) | 25 (0.41) | 185 (0.17) | 2 (0.11) |

| Shingles | 95 (0.03) | 4 (0.04) | 54 (0.03) | 2 (0.03) | 27 (0.02) | 1 (0.05) |

| Cardiorespiratory | ||||||

| Heart palpitations | 1207 (0.34) | 129 (1.37) | 831 (0.43) | 115 (1.87) | 1057 (0.95) | 21 (1.15) |

| Chest tightness/pain | 1667 (0.46) | 217 (2.14) | 1063 (0.54) | 156 (2.53) | 952 (0.86) | 35 (1.92) |

| Difficulty in breathing | 1278 (0.36) | 183 (1.81) | 889 (0.46) | 145 (2.36) | 732 (0.66) | 33 (1.81) |

| Cough | 1354 (0.38) | 253 (2.50) | 994 (0.51) | 179 (2.91) | 750 (0.67) | 39 (2.14) |

| Allergic-like | ||||||

| Hives | 721 (0.20) | 57 (0.56) | 723 (0.37) | 45 (0.73) | 421 (0.38) | 8 (0.44) |

| Itchy eyes | 830 (0.23) | 89 (0.88) | 631 (0.32) | 58 (0.94) | 543 (0.49) | 14 (0.77) |

| Throat swelling | 377 (0.10) | 30 (0.30) | 271 (0.14) | 39 (0.63) | 105 (0.09) | 5 (0.27) |

| Redness of both eyes | 362 (0.10) | 38 (0.38) | 243 (0.12) | 25 (0.41) | 242 (0.22) | 8 (0.44) |

| Facial swelling | 261 (0.07) | 18 (0.18) | 204 (0.10) | 17 (0.28) | 100 (0.09) | 3 (0.16) |

| Eyelid swelling | 278 (0.08) | 20 (0.2) | 185 (0.09) | 19 (0.31) | 131 (0.12) | 4 (0.22) |

| Anaphylaxis | 52 (0.01) | 7 (0.07) | 27 (0.01) | 7 (0.11) | 5 (0) | 0 |

| Coagulation symptomsc | 308 (0.09) | 23 (0.23) | 226 (0.12) | 22 (0.36) | 262 (0.24) | 2 (0.11) |

Note: Event categories are not mutually exclusive. Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; –, never infected; +, previously infected.

All participants were asked about injection-site reactions; only those who indicated a severe health event were provided the list of symptoms to select. Participants could select >1 symptom.

Other neurologic was defined as follows: weakness or paralysis of the arms or legs/confusion/change in personality/behavior or difficulty with urination or defecation.

Coagulation symptoms were defined as follows: symptoms of blood clot or bleeding, swelling/pain in legs/blood clot/bruising, or pinpoint dark rash.

Table 5.

Health Events Reported That Prevented Daily Activities or Resulted in Work or School Absenteeism and/or Required a Medical Consultation Within 7 Days After Dose 2 Vaccination, Among Vaccinated Participants With and Without SARS-CoV-2 Infection

| BNT162b2 | mRNA-1273 | ChAdox1-S | Mixed Schedule | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 (−) | SARS-CoV-2 (+) | SARS-CoV-2 (−) | SARS-CoV-2 (+) | SARS-CoV-2 (−) | SARS-CoV-2 (+) | SARS-CoV-2 (−) | SARS-CoV-2 (+) | ||

| Sample, n | 183 906 | 4339 | 77 954 | 2301 | 18 674 | 176 | 80 415 | 1586 | |

| Injection-site reactionsa | 90 795 (49.37) | 2462 (56.74) | 49 845 (63.94) | 1516 (65.88) | 4419 (23.66) | 59 (33.52) | 47 261 (58.77) | 950 (59.9) | |

| (95% CI) | (49.1–49.6) | (55.3–58.2) | (63.6–64.3) | (63.9–67.8) | (23.1–24.3) | (27.0–40.8) | (58.4–59.1) | (57.5–62.3) | |

| General | |||||||||

| Unwell/malaise/myalgia/ fatigue | 6517 (3.54) | 308 (7.1) | 8177 (10.49) | 283 (12.3) | 228 (1.22) | 3 (1.70) | 6084 (7.57) | 177 (11.16) | |

| Fever (≥38°C) | 1883 (1.02) | 132 (3.04) | 4343 (5.57) | 154 (6.69) | 56 (0.30) | 1 (0.57) | 2762 (3.43) | 96 (6.05) | |

| Arthritis/joint pain | 2524 (1.37) | 129 (2.97) | 3246 (4.16) | 132 (5.74) | 107 (0.57) | 1 (0.57) | 2341 (2.91) | 82 (5.17) | |

| Nausea/vomiting/diarrhea | 2610 (1.42) | 127 (2.93) | 3258 (4.18) | 105 (4.56) | 86 (0.46) | 1 (0.57) | 2176 (2.71) | 68 (4.29) | |

| Earache | 381 (0.21) | 23 (0.53) | 401 (0.51) | 16 (0.7) | 14 (0.07) | 0 | 233 (0.29) | 8 (0.50) | |

| Change in menstruation | 549 (0.49) | 28 (0.99) | 602 (1.29) | 22 (1.58) | 7 (0.07) | 0 | 355 (0.80) | 12 (1.42) | |

| Jaundice | 10 (0.01) | 1 (0.02) | 3 (0) | 1 (0.04) | 0 | 1 (0.57) | 2 (0.00) | 0 | |

| Neurologic | |||||||||

| Headache/ migraine | 4486 (2.44) | 231 (5.32) | 6040 (7.75) | 219 (9.52) | 148 (0.79) | 2 (1.14) | 4290 (5.33) | 127 (8.01) | |

| Dizziness/vertigo | 1706 (0.93) | 82 (1.89) | 2016 (2.59) | 68 (2.96) | 57 (0.31) | 1 (0.57) | 1314 (1.63) | 35 (2.21) | |

| Paresthesia | 663 (0.36) | 26 (0.60) | 598 (0.77) | 30 (1.3) | 30 (0.16) | 0 | 401 (0.50) | 16 (1.01) | |

| Fainting | 84 (0.05) | 4 (0.09) | 101 (0.13) | 6 (0.26) | 2 (0.01) | 0 | 57 (0.07) | 2 (0.13) | |

| Inability to walk | 300 (0.16) | 9 (0.21) | 447 (0.57) | 16 (0.70) | 15 (0.08) | 1(0.57) | 224 (0.28) | 8 (0.50) | |

| Loss of taste/smell | 116 (0.06) | 17 (0.39) | 162 (0.21) | 21 (0.91) | 4 (0.02) | 1(0.57) | 94 (0.12) | 4 (0.25) | |

| Loss of vision | 57 (0.03) | 7 (0.16) | 45 (0.06) | 6 (0.26) | 5 (0.03) | 0 | 24 (0.03) | 1 (0.06) | |

| Sudden unilateral facial weakness/ paralysis | 55 (0.03) | 2 (0.05) | 39 (0.05) | 5 (0.22) | 5 (0.03) | 0 | 26 (0.03) | 1 (0.06) | |

| Seizure/ convulsion | 8 (0) | 1 (0.02) | 20 (0.03) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 (0.01) | 0 | |

| Other neurologicb | 201 (0.11) | 12 (0.28) | 161 (0.21) | 7 (0.30) | 8 (0.04) | 0 | 119 (0.15) | 7(0.44) | |

| Infection | |||||||||

| Urinary tract infection symptoms | 139 (0.08) | 10 (0.23) | 136 (0.17) | 7 (0.30) | 5 (0.03) | 1 (0.57) | 76 (0.09) | 6 (0.38) | |

| Shingles | 64 (0.03) | 0 | 41 (0.05) | 1 (0.04) | 8 (0.04) | 0 | 34 (0.04) | 0 | |

| Cardiorespiratory | |||||||||

| Heart palpitations | 663 (0.36) | 41 (0.94) | 700 (0.90) | 39 (1.69) | 15 (0.08) | 0 | 421 (0.52) | 15 (0.95) | |

| Chest tightness/pain | 803 (0.44) | 48 (1.11) | 767 (0.98) | 41 (1.78) | 26 (0.14) | 0 | 445 (0.55) | 16 (1.01) | |

| Difficulty in breathing | 612 (0.33) | 46 (1.06) | 656 (0.84) | 33 (1.43) | 23 (0.12) | 0 | 367 (0.46) | 16 (1.01) | |

| Cough | 594 (0.32) | 37 (0.85) | 668 (0.86) | 41 (1.78) | 17 (0.09) | 1 (0.57) | 390 (0.48) | 11 (0.69) | |

| Allergic-like | |||||||||

| Hives | 350 (0.19) | 16 (0.37) | 384 (0.49) | 14 (0.61) | 13 (0.07) | 0 | 245 (0.30) | 2 (0.13) | |

| Itchy eyes | 383 (0.21) | 28 (0.65) | 367 (0.47) | 12 (0.52) | 19 (0.10) | 0 | 251 (0.31) | 11 (0.69) | |

| Throat swelling | 122 (0.07) | 8 (0.18) | 88 (0.11) | 3 (0.13) | 3 (0.02) | 0 | 48 (0.06) | 3 (0.19) | |

| Redness of both eyes | 146 (0.08) | 5 (0.12) | 176 (0.23) | 7 (0.30) | 5 (0.03) | 0 | 84 (0.10) | 5 (0.32) | |

| Facial swelling | 101 (0.05) | 11 (0.25) | 87 (0.11) | 2 (0.09) | 3 (0.02) | 0 | 32 (0.04) | 1 (0.06) | |

| Eyelid swelling | 88 (0.05) | 9 (0.21) | 82 (0.11) | 4 (0.17) | 6 (0.03) | 0 | 47 (0.06) | 2 (0.13) | |

| Anaphylaxis | 13 (0.01) | 2 (0.05) | 8 (0.01) | 2 (0.09) | 0 | 0 | 4 (0) | 0 | |

| Coagulation symptomsc | 115 (0.06) | 2 (0.05) | 102 (0.13) | 7 (0.30) | 12 (0.06) | 0 | 59 (0.07) | 2 (0.13) | |

Note: Event categories are not mutually exclusive. Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; –, never infected; +, previously infected.

All participants were asked about injection-site reactions; only those who indicated a severe health event were provided the list of symptoms to select. Participants could select >1 symptom.

Other neurologic was defined as follows: weakness or paralysis of the arms or legs/confusion/change in personality/behavior or difficulty with urination or defecation.

Coagulation symptoms were defined as follows: symptoms of blood clot or bleeding, swelling/pain in legs/blood clot/bruising, or pinpoint dark rash.

Table 6.

Health Events Reported That Prevented Daily Activities or Resulted in Work or School Absenteeism and/or Require a Medical Consultation Within 7 Days After Booster/Dose 3 Vaccination, Among CANVAS-COVID Participants With and Without SARS-CoV-2 Infection

| BNT162b2 | mRNA-1273 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 (−) | SARS-CoV-2 (+) | SARS-CoV-2 (−) | SARS-CoV-2 (+) | |

| Sample, n | 38 113 | 5642 | 67 634 | 9161 |

| Injection-site reactionsa | 20 201 (53.00) | 3054 (54.13) | 39 185 (57.94) | 5537 (60.44) |

| (95% CI) | (52.5–53.5) | (52.8–65.4) | (57.6–58.3) | (59.4–61.4) |

| General | ||||

| Unwell/malaise/myalgia/fatigue | 1612 (4.23) | 332 (5.88) | 3462 (5.12) | 695 (7.59) |

| Fever (≥38°C) | 492 (1.29) | 134 (2.38) | 1298 (1.92) | 271 (2.96) |

| Arthritis/joint pain | 578 (1.52) | 110 (1.95) | 1316 (1.95) | 219 (2.39) |

| Nausea/vomiting/diarrhea | 688 (1.81) | 142 (2.52) | 1401 (2.07) | 216 (2.36) |

| Earache | 142 (0.37) | 50 (0.89) | 289 (0.43) | 74 (0.81) |

| Change in menstruation | 223 (1.01) | 29 (0.86) | 329 (0.90) | 31 (0.61) |

| Jaundice | 1 (0) | 0 | 2 (0) | 3 (0.03) |

| Neurologic | ||||

| Headache/ migraine | 1260 (3.31) | 273 (4.84) | 2630 (3.89) | 543 (5.93) |

| Dizziness/vertigo | 435 (1.14) | 84 (1.49) | 861 (1.27) | 142 (1.55) |

| Paresthesia | 164 (0.43) | 26 (0.46) | 298 (0.44) | 32 (0.35) |

| Fainting | 23 (0.06) | 7 (0.12) | 45 (0.07) | 8 (0.09) |

| Inability to walk | 95 (0.25) | 17 (0.30) | 175 (0.26) | 23 (0.25) |

| Loss of taste/smell | 36 (0.09) | 37 (0.66) | 76 (0.11) | 88 (0.96) |

| Loss of vision | 32 (0.08) | 6 (0.11) | 53 (0.08) | 9 (0.10) |

| Sudden unilateral facial weakness/paralysis | 24 (0.06) | 3 (0.66) | 59 (0.09) | 6 (0.07) |

| Seizure/ convulsion | 7 (0.02) | 1 (0.02) | 10 (0.01) | 1 (0.01) |

| Other neurologicb | 46 (0.12) | 9 (0.16) | 93 (0.14) | 8 (0.09) |

| Infection | ||||

| Urinary tract infection | 44 (0.12) | 14 (0.25) | 78 (0.12) | 16 (0.17) |

| Shingles | 17 (0.04) | 4 (0.07) | 26 (0.04) | 3 (0.03) |

| Cardiorespiratory | ||||

| Heart palpitations | 269 (0.71) | 48 (0.85) | 460 (0.68) | 72 (0.79) |

| Chest tightness/pain | 310 (0.81) | 66 (1.17) | 479 (0.71) | 84 (0.92) |

| Difficulty in breathing | 309 (0.81) | 95 (1.68) | 526 (0.78) | 161 (1.76) |

| Cough | 249 (0.65) | 142 (2.52) | 492 (0.73) | 312 (3.41) |

| Allergic-like | ||||

| Hives | 113 (0.30) | 17 (0.30) | 248 (0.37) | 24 (0.26) |

| Itchy eyes | 116 (0.30) | 32 (0.57) | 252 (0.37) | 65 (0.71) |

| Throat swelling | 67 (0.18) | 21 (0.37) | 96 (0.14) | 28 (0.31) |

| Redness of both eyes | 56 (0.15) | 14 (0.25) | 114 (0.17) | 26 (0.28) |

| Facial swelling | 29 (0.08) | 6 (0.11) | 57 (0.08) | 9 (0.1) |

| Eyelid swelling | 33 (0.09) | 3 (0.05) | 69 (0.10) | 12 (0.13) |

| Anaphylaxis | 1 (0.00) | 0 | 3 (0.00) | 1 (0.01) |

| Coagulation symptomsc | 34 (0.09) | 7 (0.12) | 72 (0.11) | 4 (0.04) |

Note: Event categories are not mutually exclusive. Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviations: CANVAS-COVID, Canadian National Vaccine Safety network adapted to monitor coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine safety; CI, confidence interval; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; –, never infected; +, previously infected.

All participants were asked about injection-site reactions; only those who indicated a severe health event were provided the list of symptoms to select. Participants could select >1 symptom.

Other neurologic was defined as follows: weakness or paralysis of the arms or legs/confusion/change in personality/behavior or difficulty with urination or defecation.

Symptoms of blood clot or bleeding were as follows: swelling/pain in legs/blood clot/bruising or pinpoint dark rash.

The remaining specific health events were only solicited for those who reported a health event. Among this group, most types of events were reported more frequently by individuals with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection after dose 1, with the greatest differences being in general systemic symptoms (eg, malaise/myalgia, fever and joint pain, headache) and nausea/vomiting/diarrhea. By dose 2, these differences were still present for BNT162b2 but had decreased with mRNA-1273 and ChAdox1-S for many symptoms (Table 5). Although a greater proportion of previously infected individuals reported some neurologic symptoms such as vertigo, paresthesia, or loss of taste or smell after the first dose of mRNA vaccines, these differences were no longer apparent after the second dose. Following dose 3 the proportions reporting systemic symptoms in the previously infected group further decreased for both mRNA vaccines (Table 6). For all doses the frequency of reported symptoms was higher with mRNA-1273 compared with BNT162b2.

Onset and Duration of Health Events

Health events started within the first 24 hours of dose 1 vaccination for the majority of participants, regardless of infection status or vaccine product. However, a larger proportion of mRNA vaccine recipients who were previously infected (75% to 80%) had onset within the first 24 hours following vaccination compared with just over 50% for noninfected individuals (Supplementary Figure 1). The duration of symptoms was similar regardless of infection status, with most symptoms lasting 1–3 days (Supplementary Figure 1).

Following dose 2 vaccination, onset was generally similar among infected and noninfected participants, with a slightly higher proportion of BNT162b2-dose-2, previously infected recipients experiencing onset of symptoms within the first 24 hours of vaccination compared with noninfected participants, while the reverse was true for ChAdox1-S vaccine recipients (ie, more noninfected participants experienced onset within the first 24 hours). The duration of symptoms was similar for infected and noninfected participants for the 3 vaccine products and the mixed schedule (Supplementary Figure 2).

Following dose 3 vaccination, a larger proportion of noninfected participants experienced symptoms within the first 24 hours than infected participants, while duration of symptoms was similar between the 2 groups (Supplementary Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

For all 3 doses, health events that prevent work, daily activities, or require medical care were more likely to occur in the first week following initiation of vaccination with a COVID-19 vaccine in individuals with a prior moderate to severe SARS-CoV-2 infection and occurred more frequently after mRNA-1273 than BNT162b2, regardless of dose. The association was smaller or absent after asymptomatic or mild infections, compatible with the greater immune response that has been identified in persons with more circulating antibody [7, 8, 15]. Compared with the first dose, the association was decreased after the second and third doses for mRNA vaccines. Reassuringly, the most frequently reported AEFI symptoms were fever, myalgia, and headache, were self-limited in nature, and resolved within 24 to 72 hours after vaccination. Less than 1% required emergency care or hospitalization.

Other studies have identified more severe postvaccine symptoms occurring more frequently among people with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection only after the first dose of COVID-19 vaccine and less severe, but more frequent, reactions after the second dose [26–28]. However, a population-level postmarketing pharmacovigilance study including more than 1.1 million vaccinees from Hong Kong revealed no association between previous SARS-CoV-2 infection and AEFI or emergency room visit or hospitalization after 1 dose of vaccine [29]. This study compared infected individuals with noninfected individuals who had received 2 doses, which may account for the lack of association given the attenuation of effect we found in our data following the second dose. Additionally, the duration between doses in Canada (median of 2 months for the primary series and at least 6 months for the booster dose) was greater than that used in other countries. This longer duration may also have reduced reactogenicity.

These data have strengths and limitations. CANVAS is a multicenter, prospective study with sites across Canada and captures data from the start of the COVID-19 vaccination program. It is based on self-report; thus, we are unable to verify reported events through review of medical charts. Therefore, with the exception of injection-site reactions, the specific symptoms reported by our participants may be unrelated to the vaccine except via a temporal association. Self-reporting of health events is subjective and may be subject to recall bias and people with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection (especially if they have had a more severe infection) may be more sensitized to their own health. However, self-report data have been shown to be a reliable proxy for healthcare utilization and absenteeism for recall periods of up to 1 month [30] and self-report of AEFI has been shown to describe more serious events than those reported by healthcare providers [31]. Our study is limited in the information captured beyond 7 days. Differential misclassification of asymptomatic infection may have occurred in our nonexposed group, which could potentially bias the result toward the null. We expect this to be minimal as testing was widely available at no charge even for mild symptoms or close contacts without symptoms through the enrollment period of the study. Ethnicity was not captured until the dose 2 survey and the majority of our participants who reported ethnicity were White; thus, our results may not be fully generalizable to other groups. Participation in CANVAS required individuals to actively enroll and complete an electronic survey and such individuals may differ from the general population.

In this large, prospective observational study, health events were increased in the week following vaccination with BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, and ChAdox1-S vaccines in individuals with a prior SARS-CoV-2 infection and this association increased according to the severity of infection, which is suggestive of a dose response. The association is stronger after the first dose than after the second and third doses. The potential signal identified by our study requires further investigation via data linkage or other observational methods that do not rely on self-report. Providers should consider additional vaccine counseling on expected adverse effects for individuals previously infected with SARS-CoV-2 prior to vaccination.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Author contributions. J. A. B. conceived and obtained funding for the study and wrote and finalized the manuscript. M. S., L. V., O. G. V., J. D. K., M. P. M., K. A. T., J. E. I., A. M., G. D. S., and J. A. B. collected data and contributed to the study design. K. M. contributed to the study design. M. A. I. and H. P. S. analyzed the data. H. P. S., M. A. I., and J. A. B. accessed and verified the data. All other authors had full access to the data, reviewed the manuscript, revised it critically for important intellectual content, and read and approved the final version and accept responsibility to submit for publication.

Acknowledgments. The authors gratefully acknowledge the expert assistance provided by their public health colleagues. They thank the CANVAS coordinators and research staff for their continued contribution to the project. They also thank the CANVAS-COVID participants.

Financial support. This work was supported by the COVID-19 Vaccine Readiness funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Public Health Agency of Canada CANVAS grant number CVV-450980 and the Public Health Agency of Canada, through the Vaccine Surveillance Reference Group and the COVID-19 Immunity Task Force (reported by M. A. I., J. E. I., G. D. S., M. S., J. A. B., J. D. K., O. G. V., K. A. T., K. M., L. V., M. P. M., and P. S.). G. D. S. reports support from the Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux du Quebec. M. S. is supported via salary awards from the BC Children's Hospital Foundation and the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Julie A Bettinger, Vaccine Evaluation Center, BC Children's Hospital Research Institute, Vancouver, Canada; Department of Pediatrics, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Michael A Irvine, British Columbia Centre for Disease Control, Vancouver, Canada.

Hennady P Shulha, Vaccine Evaluation Center, BC Children's Hospital Research Institute, Vancouver, Canada; Department of Pediatrics, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Louis Valiquette, Department of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, Canada.

Matthew P Muller, Department of Medicine, Unity Health Toronto, Toronto, Canada.

Otto G Vanderkooi, Department of Pediatrics and Alberta Children's Hospital Research Institute, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada.

James D Kellner, Department of Pediatrics and Alberta Children's Hospital Research Institute, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada.

Karina A Top, Canadian Center for Vaccinology, IWK Health and Department of Pediatrics, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada.

Manish Sadarangani, Vaccine Evaluation Center, BC Children's Hospital Research Institute, Vancouver, Canada; Department of Pediatrics, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Allison McGeer, Sinai Health System and University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada.

Jennifer E Isenor, College of Pharmacy and Canadian Center for Vaccinology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada.

Kimberly Marty, Vaccine Evaluation Center, BC Children's Hospital Research Institute, Vancouver, Canada.

Phyumar Soe, Vaccine Evaluation Center, BC Children's Hospital Research Institute, Vancouver, Canada.

Gaston De Serres, CHU de Québec-Université Laval, Quebec City, Canada; Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec, Quebec City, Canada.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. Available at: https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed 15 July 2022.

- 2. Dan JM, Mateus J, Kato Y, et al. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science 2021; 371:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kim P, Gordon SM, Sheehan MM, Rothberg MB. Duration of SARS-CoV-2 natural immunity and protection against the Delta variant: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2022; 24:e185–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nonaka CKV, Franco MM, Gräf T, et al. Genomic evidence of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection involving E484K spike mutation, Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis 2021; 27:1522–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pulliam JRC, van Schalkwyk C, Govender N, et al. Increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection associated with emergence of Omicron in South Africa. Science 2022; 6:eabn4947. doi:10.1126/science.abn4947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. BC Center for Disease Control. Measuring vaccination impact & coverage. Available at: http://www.bccdc.ca/health-info/diseases-conditions/covid-19/covid-19-vaccine/measuring-vaccination-impact-coverage. Accessed 15 March 2022.

- 7. Gobbi F, Buonfrate D, Moro L, et al. Antibody response to the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in subjects with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection. Viruses 2021; 13:422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Goel RR, Apostolidis SA, Painter MM, et al. Distinct antibody and memory B cell responses in SARS-CoV-2 naïve and recovered individuals following mRNA vaccination. Sci Immunol 2021; 6:eabi6950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ali H, Alahmad B, Al-Shammari AA, et al. Previous COVID-19 infection and antibody levels after vaccination. Front Public Health 2021; 9:778243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ebinger JE, Fert-Bober J, Printsev I, et al. Antibody responses to the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine in individuals previously infected with SARS-CoV-2. Nat Med 2021; 27:981–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:403–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Voysey M, Clemens SAC, Madhi SA, et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. Lancet 2021; 397:99–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mathioudakis AG, Ghrew M, Ustianowski A, et al. Self-Reported real-world safety and reactogenicity of COVID-19 vaccines: a vaccine recipient survey. Life 2021; 11:249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Raw RK, Kelly CA, Rees J, Wroe C, Chadwick DR. Previous COVID-19 infection, but not long-COVID, is associated with increased adverse events following BNT162b2/Pfizer vaccination. J Infect 2021; 83:381–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Krammer F, Srivastava K, Alshammary H, et al. Antibody responses in seropositive persons after a single dose of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine. N Engl J Med 2021; 384:1372–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Joshi RK, Muralidharan CG, Gulati DS, et al. Higher incidence of reported adverse events following immunisation (AEFI) after first dose of COVID-19 vaccine among previously infected health care workers. Med J Armed Forces India 2021; 77:S505–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baldolli A, Michon J, Appia F, Galimard C, Verdon R, Parienti JJ. Tolerance of BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in patients with a medical history of COVID-19 disease: a case control study. Vaccine 2021; 39:4410–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. De Serres G, Gariepy MC, Coleman B, et al. Short and long-term safety of the 2009 AS03-adjuvanted pandemic vaccine. PLoS One 2012; 7:e38563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bettinger JA, Rouleau I, Gariepy MC, et al. Successful methodology for large-scale surveillance of severe events following influenza vaccination in Canada, 2011 and 2012. Eurosurveillance 2015; 20:21189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. De Serres G, Billard M, Gariépy M, Rouleau I, Toth E, Landry M. Rapport final de surveillance de la sécurité de la vaccination des jeunes de 20 ans et moins contre le méningocoque de sérogroupe B au Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean. Quebec City, Canada: Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ahmed MA, Naus M, Singer J, et al. Investigating the association of receipt of seasonal influenza vaccine with occurrence of anesthesia/paresthesia and severe headaches, Canada 2012/13–2016/17, the Canadian Vaccine Safety Network. Vaccine 2020; 38:3582–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bettinger JA, Sadarangani M, De Serres G, et al. The Canadian National Vaccine Safety Network: surveillance of adverse events following immunisation among individuals immunised with the COVID-19 vaccine, a cohort study in Canada. BMJ Open 2022; 12:e051254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.. Statistics Canada. Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS)—annual component—2020. Available at: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3Instr.pl?Function=assembleInstr&a=1&&lang=en&Item_Id=1262397. Accessed 18 December 2020.

- 24. Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005; 173:489–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. National Advisory Committee on Immunization . An Advisory Committee Statement National Advisory Committee on Immunization: guidance on booster COVID-19 vaccine doses in Canada—update December 3, 2021. Available at: 5 August2022https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/immunization/national-advisory-committee-on-immunization-naci/guidance-booster-covid-19-vaccine-doses.html. Accessed 5 August 2022.

- 26. Ebinger JE, Fert-Bober J, Printsev I, et al. Antibody responses to the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine in individuals previously infected with SARS-CoV-2. Nature Med 2021; 27:981–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tré-Hardy M, Cupaiolo R, Papleux E, et al. Reactogenicity, safety and antibody response, after one and two doses of mRNA-1273 in seronegative and seropositive healthcare workers. J Infect 2021; 83:237–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Raw RK, Rees J, Kelly CA, Wroe C, Chadwick DR. Prior COVID-19 infection is associated with increased adverse events (AEs) after the first, but not the second, dose of the BNT162b2/Pfizer vaccine. Vaccine 2022; 40:418–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gottfredsson M, Reynisson IK, Ingvarsson RF, et al. Comparative long-term adverse effects elicited by invasive group B and C meningococcal infections. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53:e117–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Short ME, Goetzel RZ, Pei X, et al. How accurate are self-reports? Analysis of self-reported health care utilization and absence when compared with administrative data. J Occup Environ Med 2009; 51:786–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Clothier HJ, Selvaraj G, Easton ML, Lewis G, Crawford NW, Buttery JP. Consumer reporting of adverse events following immunization. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2014; 10:3726–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.