Abstract

Autistic individuals often struggle to find and maintain employment. This may be because many workplaces are not suited to autistic individuals’ needs. Among other difficulties, many autistic employees experience distracting or disruptive sensory environments, lack of flexibility in work hours, and unclear communication from colleagues. One possible way of mitigating these difficulties is for employees to disclose their diagnosis at work. While disclosure may increase understanding and acceptance from colleagues, it can also lead to discrimination and stigma in the workplace. Research has shown that disclosure outcomes are often mixed, but it is unclear what factors are associated with either positive or negative outcomes of disclosure for autistic people. This study aimed to identify these factors and explore the reasons why autistic employees choose to disclose or to keep their diagnosis private. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 24 clinically-diagnosed autistic adults (12 male and 12 female) who were currently, or had been, employed in the UK (mean age = 45.7 years). Through thematic analysis, we identified three main themes under experiences of disclosure: 1) A preference for keeping my diagnosis private; 2) The importance of disclosure in the workplace; and 3) Disclosure has mixed outcomes. We also identified three factors associated with disclosure outcomes: understanding of autism, adaptations, and organisational culture. These results have implications for improving inclusive practices on both the individual and organisational level to ensure more positive disclosure experiences for autistic employees.

Keywords: Autism, employment, disability, discrimination, diagnostic disclosure

Introduction

Autistic adults have lower employment rates compared to other disability groups in the UK (National Autistic Society, 2016). An estimated 16% of autistic people are in full-time employment and 32% in any form of paid work, compared to 47% for other disability groups and 80% employment for the general adult population (National Autistic Society, 2016). Despite these numbers, it is clear that the majority of autistic adults want to work (Baldwin et al., 2014; Bennett & Dukes, 2013; Wilczynski et al., 2013), and that there are numerous important benefits from employment including increased independence, a social network, the opportunity to contribute to society, and higher quality of life (Roux et al., 2013).

The low employment rates may be, in part, due to specific challenges that arise from being on the autistic spectrum. Autism is a condition marked by stereotyped, repetitive behaviours and differences in social communication (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Social differences may be particularly challenging in the workplace, for example differences in social communication styles, and struggling with lack of clarity in other people’s language (Remington & Pellicano, 2019). This can make interacting with colleagues difficult for autistic people (Howlin et al., 2005; Sperry & Mesibov, 2005), which may be misinterpreted by others in the workplace, leading to negative perceptions. These challenges are not limited to established roles. The recruitment stage can also pose difficulties for autistic adults, due to the social interaction that is integral to most job interviews (Bublitz et al., 2017; Mawhood & Howlin, 1999; Morgan et al., 2014; Sarrett, 2017; Smith et al., 2014; Strickland et al., 2013).

Disclosing an autism diagnosis has been suggested as one way to reduce misunderstandings and create favourable impressions (Sasson & Morrison, 2017). Research has shown that non-autistic people’s first impressions of autistic people improved with disclosure (Sasson & Morrison, 2017), and these impressions further improved when the recipient of the disclosure had more autism knowledge. This improvement has also been demonstrated in workplace environments, where employers who were more knowledgeable about autism showed an increased willingness to hire autistic candidates (McMahon et al., 2020).

While disclosure can greatly improve impressions of autistic people in certain situations, it can also lead to discrimination–especially when the recipient has high stigma toward autism (Morrison et al., 2019). Unfortunately, discrimination toward hiring autistic people does exist. In studies involving autistic job candidates, potential employers showed a clear preference toward hiring non-autistic over autistic individuals (Ameri et al., 2018; Flower et al., 2019). Accordingly, studies have shown that autistic employees often choose not to disclose their diagnoses due to the fear of this type of discrimination from employers and colleagues (Morris et al., 2015; Sarrett, 2017). As many autistic people are aware of this risk of discrimination, they may also feel the need to engage in camouflaging as a result of their decision not to disclose. Camouflaging, also called “masking”, is the hiding of one’s autistic traits in social situations so as to appear typical or fit in with non-autistic individuals (Hull et al., 2017). There is some evidence that autistic females tend to engage in camouflaging behaviours more than autistic males in social situations (Hull et al., 2019; Schuck et al., 2019; Wood-Downie et al., 2021); in workplaces, this may mean females are less likely to disclose their diagnosis. Other literature on gender-related differences may offer some clues as to how disclosure experiences for male and female employees might differ. Baldwin and Costley (2016) found that a significantly higher proportion of autistic females identified social interaction as one of the worst aspects of employment as compared to autistic males interviewed in the same study. This may therefore lead to gender-related differences in workplace experiences of disclosure and camouflaging; however, this is still a largely unexplored topic, and there is still uncertainty surrounding disclosure for both males and females in the autistic community.

In relation to this uncertainty about whether or not to disclose and the mixed outcomes of disclosure, our own preliminary research has shown that the decision to disclose in the workplace is a complex one (Romualdez, Heasman, Davies, Walker, and Remington, 2021). Autistic adults identified many positive outcomes of disclosure. One such outcome was appropriate workplace adjustments, including more flexible work hours, noise-cancelling headphones, and the option to work from home a certain number of days a week. Other examples of positive outcomes given by autistic participants were successful recruitment, legal protections, and increased understanding and acceptance from others. However, a number of negative outcomes were also reported. Autistic adults experienced bullying and purposeful discrimination, as well as a lack of support, understanding, and acceptance in the workplace (blinded for review). Indeed, many disclosure decisions were related to autistic adults’ consideration of how others would respond to their autism diagnosis. Desire for increased understanding and acceptance was the most common reason cited by autistic individuals for choosing to disclose while fear of the negative perceptions of others was the most common reason not to disclose (blinded for review). This reflected a clear focus on the attitudes and perceptions of others that contradicted previous beliefs about autistic people being socially indifferent (Dodd, 2005). Further, despite a number of autistic employees disclosing in order to access workplace adjustments, many autistic people are not satisfied with the adjustments they received after they disclosed (Lindsay et al., 2019; Romualdez et al., 2020).

Clearly, disclosing an autism diagnosis is a complex process, and the potential mixed outcomes of disclosure may contribute to autistic employees’ struggle with the decision. While our previous study showed several possible outcomes of disclosure, it remains unknown what factors are associated with these various outcomes. Existing literature on the disclosure of other conditions may provide clues as to what could lead to positive or negative outcomes for autistic people. There is evidence that the reaction of the confidant (i.e., the recipient of the disclosure) may be one of the most important factors affecting the outcome of disclosure (Major et al., 1990; Rodriguez & Kelly, 2006). Chaudoir and Fisher (2010) had a similar focus on the social aspect of disclosure. The researchers based their Disclosure Process Model (DPM) on the experiences of individuals with concealable stigmatised identities, specifically those who had experiences related to abuse or assault, mental health conditions, or HIV. They identified three mediators by which disclosure of such an identity may result in either a positive or negative outcome: alleviation of inhibition, social support, and changes in social information (Chaudoir & Fisher, 2010). Alleviation of inhibition refers to the lessening of psychological stress for the person who discloses; social support refers to how others might help those who disclose; and changes in social information arise because disclosure necessarily alters the dynamic between the discloser and confidant, either in a positive or negative way (Chaudoir & Fisher, 2010). While autism is an entirely unique condition and comparisons to other stigmatised identities may be limited, these mediators may still be relevant to our understanding of the outcomes of autism disclosure.

Understanding the relationship between characteristics of a workplace and resulting disclosure experiences is crucial if we are to promote good outcomes and effectively advise autistic people on how and when disclosure is optimal. The current study examines this issue and is, to our knowledge, the first UK-based qualitative study to specifically examine the disclosure experiences of autistic adults in the workplace. By identifying the determinants of positive outcomes of disclosure, we aim to help employers and organisations improve the disclosure experiences and ultimately the employment outcomes of autistic individuals.

Method

Participants

Participants in the current study were 24 clinically-diagnosed autistic adults with a mean age of 45.7 years (range = 26 – 66 years). The sample was predominantly White, evenly split between males and females, and participants were – or had previously been – employed across a variety of sectors (see Table 1 for full participant information). Participants were recruited via a database of those who had previously taken part in research at [The Centre for Research in Autism and Education at the UCL Institute of Education], social media, and the researchers’ own networks. For the present study, participation was limited to those who reported a formal diagnosis of autism. We acknowledge that self-diagnosis of autism is valid and that it is important to include the voices of self-diagnosed autistic people in research. However, many autistic people choose to disclose in order to obtain legal protections or workplace adjustments based on a clinical diagnosis. We expect those without a clinical diagnosis to have different reasons for disclosing and different experiences, which we aim to explore in future research.

Table 1.

Participant information.

| N = 24 | |

|---|---|

| Gender | 12 females; 12 males |

| Ethnicity | 22 White; 1 Black; 1 Mixed |

| Mean age (range) | 45.7 years (26 – 66 years) |

| Age when diagnosed | Under 18: n = 1 (4%) |

| 18–24: n = 0 (0%) | |

| 25–34: n = 6 (25%) | |

| 35–44: n = 6 (25%) | |

| 45–54: n = 7 (29%) | |

| 55–64: n = 4 (17%) | |

| Method of diagnosis | All clinically diagnosed |

| Employment status | 19 employed full-time; 3 employed part-time; 2 formerly employed |

| Mean years at current job (range) | 8.6 years (1 month – 25 years) |

| Employment sectors represented | Administration, Communications and Marketing, Creative and Performing Arts, Education, IT, Public Sector, Research, Retail, Self-Employed (Entrepreneur) |

| Current income level | Below £10,000: n = 2 |

| £10,001-£20,000: n = 6 | |

| £20,001-£30,000: n = 10 | |

| £30,001-£40,000: n = 2 | |

| £40,001-£50,000: n = 1 | |

| Above £50,000: n = 1 | |

| Not known (did not answer): n = 2 | |

| Level of disclosure | 9 disclosed selectively |

| 15 disclosed to everyone | |

| Self-reported | Mental health challenges: n = 19 |

| Co-occurring | ADHD: n = 4 |

| Conditions | Learning condition: n = 2 |

| Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome: n = 1 | |

Measures

The interview schedule consisted of questions about previous and current employment experiences, as well as questions specifically for individuals who were actively seeking employment. The questions were divided into three sections: personal background/demographic information, employment background, and diagnostic disclosure. The schedule included main questions about employment and disclosure (e.g., “Are you currently working?”) as well as probing questions (e.g., “Do you think you might have had a different experience if you had chosen to/not to disclose?”). See online Appendix A for the full interview schedule.

Procedure

Interviews were conducted in person (n = 2), over the phone (n = 6), or through video call (n = 8), online chat (n = 2), or email (n = 6), depending on participant preference. These options were provided in order to make the study as inclusive as possible. In-person, phone, video call, and online chat interviews lasted between 30 and 45 minutes. For interviews conducted through email, we sent participants the interview questions in a Word document for them to complete in their own time and send back to us. Ethical approval for this study was granted by (The UCL Institute of Education) and all participants gave written informed consent to take part, and for their interview to be recorded.

Data analysis

All in-person, phone, and video call interviews were transcribed verbatim and, together with the online chat and email interviews, were imported into the QSR NVivo 12 Pro (2018) qualitative data analysis programme for coding. We used thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2019) to identify themes and sub-themes from the interview transcripts. MR conducted the initial analysis using an open coding method, which involved categorising sections of text from the data without any existing framework. The coding framework was developed by creating themes from these sections of text, then further refining these themes into various sub-themes. To identify factors associated with the outcomes of disclosure, MR coded only the sections of text where participants explicitly stated that a certain adaptation, event, or characteristic of a workplace/co-worker led to a certain disclosure outcome. Through initial coding, MR identified overarching factors that were related to outcomes of disclosure and further refined these into the three factors presented in the results section of this paper. MR interpreted participants’ statements about the factors that led to certain outcomes of disclosure to determine whether they had successful or unsuccessful disclosure experiences. AR conducted secondary analysis by reviewing quotes and their relevant sub-themes. Both researchers then met several times to reach an agreement on the themes and sub-themes, building a thematic map that represented the data as accurately as possible. In the interest of confidentiality, participant names are pseudonymised in this study using assigned ID numbers attached to their quotes.

Results

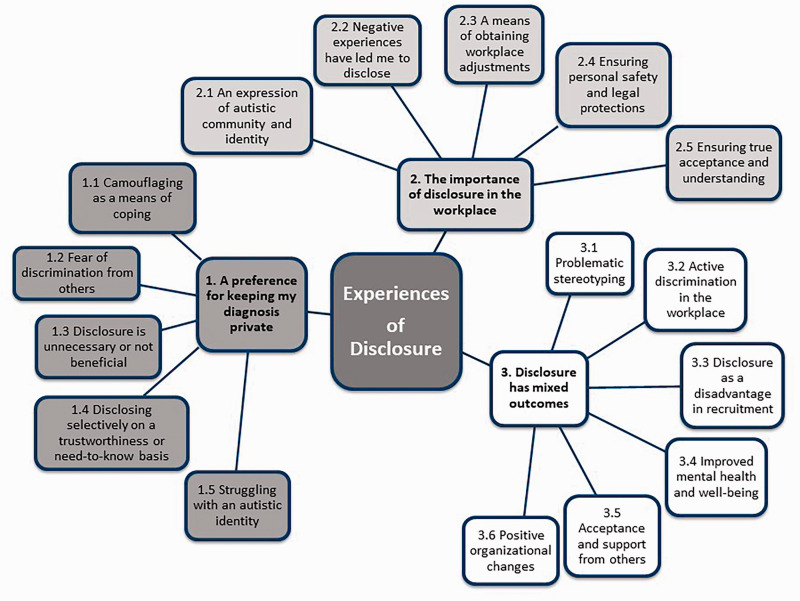

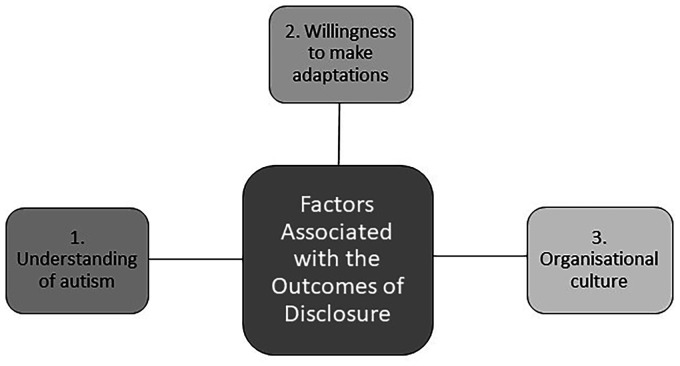

The themes and sub-themes that we identified through thematic analysis of the interview transcripts encompassed a variety of views on whether disclosure was beneficial, and the mixed outcomes of disclosure (see Figure 1). We also identified the factors associated with outcomes of the disclosure (see Figure 2). Notably, quotes from both male and female participants were coded into all of the sub-themes, with no sub-themes associated with only one gender. The complete table of themes, sub-themes and illustrative quotes can be found in online Appendix B.

Figure 1.

Thematic map of participants’ experiences of disclosure.

Figure 2.

Factors associated with the outcomes of disclosure.

Experiences of disclosure

A preference for keeping my diagnosis private

For many, there was a desire to maintain privacy about their diagnosis when possible. Nine participants had chosen not to disclose in previous roles, or only disclosed selectively in their current roles. Participants spoke about using camouflaging as a means of coping with difficult situations: “I do it automatically [at work], and I’ve done it since I was a child, because I realised quite early on that I was different to other children. And particularly, once I got to high school, I realised that if I didn’t want to be bullied anymore, I had to pretend I was like other girls.” (p. 6). Another participant stated, “Obviously, before your diagnosis, you don't know you're masking. You don't know you're doing it. You just get the sense that you don't function the way other people do, and that you're trying to learn things in a kind of mechanical way in order to fit in.” (p. 4). Many of the participants who actively hid their diagnosis also talked about the fear of discrimination from others as a reason behind their decision: “By not disclosing, I do not give people that weapon to use autism as a blanket reason against me—or a blanket excuse if they are trying to be kind or protect me.” (p. 24) One participant said, “My shortcomings could be attributed to my autism and this is therefore seen negatively. I also feel as though asking for accommodations might be seen as looking for an easier way in, or that it might be perceived that I am using autism as an ‘excuse’ for my shortcomings.” (p. 21) Others simply saw no reason to disclose, saying that disclosure is unnecessary or not beneficial. Participants stated, “I have not disclosed to any of my colleagues for this job, simply because it didn’t seem relevant” (p. 24) and, “It’s a small piece of work, not very intense, and I don’t see a reason to disclose. It’s not worth the effort.” (p. 7)

Several individuals spoke about keeping their diagnosis as private as possible by disclosing selectively on a trustworthiness or need-to-know basis: “I haven’t actually told any kind of line managers or anyone in that kind of formal way, it’s just people who I’ve felt comfortable telling.” (p. 12). One participant also said, “I would usually tell somebody that had a direct impact on my role such as a manager and I would consider whether I trusted them to treat that information in a sensible and kind way.” (p. 11).While some participants chose to keep their autism diagnosis private for the reasons mentioned above, some chose not to disclose due to difficulty accepting or understanding their diagnosis. These individuals spoke about struggling with an autistic identity, especially those who had received their diagnosis within the last few months or years. One participant stated that, “My motivation to be normal was because I hadn’t accepted my diagnosis. I definitely masked as much as I could and avoided impossible tasks.” (p. 13). Similarly, another participant spoke about struggling with their diagnosis: “I have spent most of my life under the impression that I am not a proper person and trying to hide it.” (p. 3).

The importance of disclosure in the workplace

In contrast to the views outlined above, a number of participants highlighted how important it was for them to disclose at work. In particular, many participants felt that disclosure was not just for themselves but for other autistic people who might be also be dealing with difficulties in the workplace. These participants discussed disclosure as an expression of autistic community and identity. They spoke about how their autistic identity was important to them, and how they felt a sense of obligation to disclose in order to pave the way for other autistic people: “I have spent most of my life under the impression that I am not a proper person and trying to hide it. There came a point when I thought this was not going to help younger autistic people.” (p. 14) One participant spoke about their passion for advocacy, saying, “In one way, it’s been one of the best things that’s ever happened to me, because I’m absolutely passionate about it …I’ve done a lot of stuff at work in promoting neurodiversity and explaining to people exactly what it is, and what it’s like to be an autistic person, and what amazing qualities we have, and what we can bring to work.” (p. 6)

While some felt that it was their responsibility to disclose, other participants felt that they had to disclose due to certain situations that they found themselves in. These participants explained how negative experiences have led me to disclose. In some cases, this referred to previous situations where choosing not to disclose had resulted in negative outcomes; this prompted participants to make the decision to disclose so as to avoid the same outcomes. One participant said, “I disclosed to my manager because I just wanted to ensure that nothing happened like in my previous job and so I thought it was best to bring it up as soon as I could.” (p. 11) In other cases, the participant disclosed once they encountered issues at work (i.e., retrospective disclosure): “I got into a situation at work where I was being bullied and I didn’t want it to be thrown at me, so I wanted it to be known that I had Asperger’s so it wasn’t just that I was antisocial or difficult.” (p. 2)

For many, disclosure was seen as a means of obtaining workplace adjustments (“The decision was taken so as not to have any problems. Now no one asks me to go down the night before for meetings. They are organised to allow for early morning travel.” (p. 15)) or ensuring personal safety and legal protections: “I think disclosure is important, because it has meant that I have the protections that go along with the Equalities Act. That is 100% absolutely crucial in my situation.” (p. 3)

Lastly, participants spoke about disclosure as a means of ensuring true acceptance and understanding: “There’s no point going to work somewhere if they don’t know in advance and are not accepting and welcoming of me right from the start. I’d just encounter more problems and end up being fired probably. So at least it filters out the places that would be bad for me to work.” (p. 17)

Disclosure has mixed outcomes

Just as participants had mixed views on whether to disclose, we also identified mixed outcomes of disclosure, sometimes even within the same situation.

For some, disclosure resulted in problematic stereotyping: “… unspoken assumptions, people assuming I’m good at everything because I am good at one thing, and people assuming I am terrible at everything because I am terrible at one thing. In other words, the assumption of a flat autistic profile is hugely problematic.” (p. 22) Sometimes, the negative impact of disclosure went as far as active discrimination in the workplace, with one participant describing this situation: “[She] asked me to speak privately and told me, ‘I didn’t mean it that way, it’s just that everyone else would have understood.’ Really? Are you actually saying that you spoke to me disrespectfully because of my autistic traits? So that was direct discrimination.” (p. 21)

Some participants also viewed disclosure as having a negative impact on hiring practices, referring to disclosure as a disadvantage in recruitment. One participant talked about a situation where disclosure led to not getting the job: “They had been very happy with my written tasks during the application process, but the feedback I got about the interview was that I didn’t fit in there, and they were concerned I’d need adjustments to the training process. Which are both thinly-veiled code for ‘You’re too autistic.’” (p. 18)

While these negative outcomes were common in the data, positive outcomes were also frequently discussed. Participants spoke about having improved mental health and well-being after disclosing their autism diagnosis: “I have become much more open about it because the response to disclosure has always been positive, so I feel able to mask a little less and live more authentically, which is good for the well-being.” (p. 19) They also gained acceptance and support from others, with one participant expressing that, “I’ve had some good experiences certainly as well and I feel a lot better in terms of people accepting me.” (p. 9) This acceptance and support led to managers’ increased willingness to help their autistic employees: “The managers were very interested in learning more about autism. The two managers supported me on the shop floor and at the tills.” (p. 13)

Disclosure sometimes had a wider impact; not only impacting the individual but also leading to positive organisational changes. One participant, despite being made redundant, still spoke about a welcome effect of disclosing an autism diagnosis: “I don’t regret disclosing in that organisation because I believe it did good even for the organisation. Now they have a proper procedure where, if someone needs a disability adjustment, it is dated, it is in black and white, it can be followed.” (p. 21)

Factors associated with the outcomes of disclosure

We identified three factors that appeared to be linked to whether disclosure had positive or negative outcomes: understanding of autism, willingness to make adaptations, and organisational culture (see Figure 2).

Understanding of autism

Colleagues’ and employers’ understanding of autism appeared to be associated with whether the disclosure of an autism diagnosis had a positive or negative effect. Where colleagues had prior knowledge and understanding of autism, disclosure experiences were often positive: “A colleague I was working quite closely with said, ‘I understand, my son has autism’ so that was really encouraging, that was a positive experience.” (p. 7) However, a lack of understanding was typically associated with more negative outcomes: “The third job didn’t show any understanding at all. They were busy and short-staffed and the manager was only temporary. There was a high staff turn around there. So, the disclosure had no effect at all.” (p. 13)

Willingness to make adaptations

We also identified a second factor related to disclosure outcomes: the willingness to make adaptations in the workplace for autistic individuals. In situations where appropriate adjustments were made, participants often had positive experiences: “Some adaptations have been made without me asking. Employer is tolerant of my bad memory, which I really appreciate and need. She reminds me of some things.” (p. 22) Participants spoke about negative outcomes when employers were unwilling to make these adjustments: “On their part they told me that they didn’t know and then when I did disclose it in an HR meeting, I said that I would like some special agreed adjustments to be put in place but they refused.” (p. 11)

Organisational culture

Acceptance and understanding from colleagues, as well as willingness to make adaptations, were often reflective of the wider organisational culture. Some participants spoke about their workplaces as being more inclusive and understanding of disability, which was linked to positive outcomes of disclosure: “Because I am disabled, I now get to work on our disabled resources! So, when the people in the office or the advisors come across someone that has additional needs, they will redirect them to me.” (p. 3) Others spoke about some organisations having a negative view of disability, which could lead to negative outcomes: “I think unfortunately there are certain negative attitudes towards people with disabilities and it’s depending on the culture of where you work. You might make your own employment position less secure by disclosing so I would advise people to consider whether or not it is a good idea according to the culture of the organisation.” (p. 9)

Discussion

The decision to disclose an autism diagnosis is a struggle for many autistic individuals, especially within a workplace environment. This struggle can be compounded by the uncertainty surrounding the outcomes of disclosure. Our study aimed to decrease this uncertainty by identifying factors in the workplace associated with the various outcomes of disclosure. We first asked people if they had disclosed and why, then questioned them about the outcomes of their disclosure decision.

Disclosure is a process that begins with weighing the decision to disclose. Our study identified many participants who chose to keep their diagnosis private or to disclose selectively based on trust or necessity. Withholding their diagnosis involved the use of camouflaging as a coping mechanism, which previous studies have identified in everyday social situations (Cage & Troxell-Whitman, 2019; Hull et al., 2017; Schneid & Raz, 2020) and which we have identified as a strategy also employed by autistic individuals in the workplace. Research has identified an association between camouflaging and gender, with higher rates of camouflaging behaviours observed in females compared to males (Hull et al., 2019; Schuck et al., 2019; Wood-Downie et al., 2021). Contrary to these findings, the results of the current study did not confirm this association; both male and female participants spoke about using camouflaging to cope within their workplace environments. In fact, our results showed no differences in disclosure experiences based on gender, as both male and female participants were represented under each sub-theme. Main reasons to avoid disclosing were the fear of discrimination from others, and the belief that disclosure is unnecessary or not beneficial. These findings were consistent with those of our previous study (Romualdez et al., 2021) and those of Johnson and Joshi (2014), who identified fear of discrimination as a common reason why autistic employees do not disclose. We also found that individuals struggling with their autistic identity chose not to disclose their diagnosis to their employers or colleagues.

Conversely, many participants did disclose widely within the workplace, and spoke about disclosure as an expression of their autistic identity and a responsibility to the autistic community. There is growing evidence of a link between autistic identity and disclosure (Cage & Troxell-Whitman, 2020), and our results show that this is also relevant to the decision to disclose at work. Consistent with previous findings (Romualdez et al., 2020), we also found that people chose to disclose for adjustments, legal protections, and increased understanding and acceptance, as well as in response to negative experiences.

The mixed outcomes of disclosure determined by past research (Lindsay et al., 2019; Romualdez et al., 2020) were also confirmed by the current study. These included negative outcomes (i.e., problematic stereotyping, active discrimination, and disadvantages in recruitment) as well as positive ones: improved mental health and well-being, acceptance and support from others, and positive organisational changes.

The goal of the current study was to understand what might contribute to positive or negative outcomes after the disclosure of an autism diagnosis. By analysing the participants’ experiences, we suggest three factors associated with these outcomes: understanding of autism, adaptations, and organisational culture. A better understanding of autism for both employers and colleagues of autistic individuals is associated with positive disclosure experiences. The participants in our study commented that when others in the workplace had more knowledge of autism and showed a greater understanding of autistic traits, this led to better disclosure outcomes. The importance of colleagues’ understanding of autism is in line with research outside the employment field which has shown that increased autism knowledge in social situations may lead to more positive outcomes of disclosure (Sasson & Morrison, 2017). Similarly, disclosure had negative outcomes when people already had a negative view of autism (Morrison, 2019). This demonstrates how the reaction of the confidant is connected to the outcome of disclosure, as seen in research on other stigmatised identities (Major et al., 1990; Rodriguez & Kelly, 2006). Our findings show that this is also relevant to autistic individuals; diagnostic disclosure may be successful based on autism knowledge and therefore the understanding, and favourable reaction, of the recipient of the disclosure.

One way in which recipients of autism disclosure can react positively is to make appropriate adaptations for the autistic individual. The willingness to make adaptations appears to be a second factor associated with disclosure outcomes. Participants who received adaptations that were both timely and appropriate to their needs often associated these with positive experiences of disclosure. These workplace adjustments included changes to the work environment, such as blue light filters for computer screens and noise cancelling headphones, as well as adjustments to workplace policy. Some examples mentioned by participants were being allowed to work from home on certain days of the week and having an assigned desk despite hot desking being used in their workplaces. Conversely, some autistic adults spoke about going through a long, protracted process to obtain adjustments, not receiving the right adjustments, or encountering resistance from employers toward making these adjustments; these individuals had negative experiences of disclosure. Research has shown that obtaining workplace adjustments is a common reason to disclose; in fact, many autistic adults only disclose in order to receive adjustments (Romualdez et al., 2020). However, autistic people are often dissatisfied with the adjustments made by employers and colleagues (Lindsay et al., 2019; Romualdez et al., 2020), and in such cases, the decision to disclose may be viewed negatively. It is therefore crucial to ensure that, following disclosure, appropriate adaptations are put in place to improve productivity and work participation, and also support well-being and mental health (Baanders et al., 2001; Charmaz, 2010).

While understanding autism and making adaptations on the individual level are important, it is an inclusive organisational culture that underpins both of these determinants. Our findings showed that autistic employees whose workplaces were perceived to be more accepting of diversity also experienced positive outcomes after disclosing their diagnosis. We found that an inclusive workplace culture often involved a better understanding of autism from employers and colleagues, as well as a greater willingness to make adaptations. This is consistent with research on disabled employees more generally which highlights characteristics of the organisation, managers and employees that pose barriers to employment for disabled individuals (Stone & Colella, 1996). Two main influences emerged: organisational leadership, and human resource personnel. Regarding the former, Schein (2017) underscored the importance of leaders in not only representing organisational culture but also being agents of change in their workplaces. While organisations as a whole must adopt inclusive practices, it is organisation leaders such as CEOs and managers who can influence the attitudes of their employees toward diversity. This has a direct impact on how autistic employees can thrive in their workplace environments.

In addition to the role of leadership, Bruyere et al. (2003) emphasised the importance of the attitudes of human resource personnel toward supporting disabled employees, and identified this as an influencing factor on the ability of these employees to maintain their jobs. As the avenue by which organisations support and protect their employees, human resource departments are representative of organisational culture. An inclusive organisation must show an interest in supporting all of its employees and creating an environment that accommodates their different needs. This naturally influences employees to be more understanding and willing to adapt for autistic individuals. In fact, this type of workplace may not even necessitate disclosure by its autistic employees if adjustments, such as flexible working hours and quiet spaces, are already in place for every employee. In truly inclusive workplaces, disclosure is entirely the choice of the autistic employee and not a necessity.

Overall, our findings lead to key recommendations based on the factors associated with disclosure outcomes. We recommend three specific practices that will facilitate the development of better understanding of autism, meaningful workplace adjustments, and inclusive organisational cultures. First, organisations must work to increase the understanding of autism within their workplaces, but general autism training can often promote problematic stereotypes and ultimately be harmful to autistic employees. Instead, we recommend individualised autism training, ideally involving the autistic employee. This will ensure that the understanding of autism is tailored to the employee’s own experiences, strengths, and needs. Second, while disclosure often leads to workplace adjustments, disclosure must also be supported by having the right infrastructure in place to ensure adjustments are both timely and appropriate. Having a clear process for disclosure is merely the first step; employers need to make sure that there is follow-through with supports put in place so that disclosure has tangible, lasting effects. We also recommend regular evaluations by autistic employees of the adjustments put in place to ensure satisfaction, and a pathway for autistic employees to provide feedback when adjustments are not working.

The above recommendations are targeted toward employers, whom we urge to take more of an initiative in improving the disclosure experiences of their autistic employees. The current study identified positive organisational changes as one outcome of disclosure, but these changes were often brought on by the autistic individuals themselves. The organisations in these situations were forced to define their disclosure and adjustment protocols because their autistic employees either took legal action or demanded change. While making these changes is a step in the right direction, we recommend that organisations take a more proactive approach to embracing and supporting diversity, rather than relying on their disabled employees to show them where they can improve. This could involve diversity training and clear guidelines on legal protections for disabled employees, as well as using hiring practices that do not unfairly disadvantage autistic people (e.g., practical evaluations rather than face-to-face interviews).

While we urge employers and organisations to adapt their businesses to become more inclusive, we also recognise that the push for more inclusive workplace environments may not bring about immediate change. It may, unfortunately, take some time before the movement toward acceptance of neurodiversity in workplaces translates to practices that are beneficial for autistic individuals. We therefore have certain recommendations for autistic employees and job seekers who may currently be weighing the decision to disclose. Autistic employees should first seek to review their organisation’s policies on disclosure and legal protections for disabled employees. There may be some precedent within the organisation for disclosure of disabilities, which can help autistic employees identify how their workplaces respond to disclosure. In workplaces where the outcomes of disclosure may be unclear, disclosing selectively at first to an immediate supervisor will give the autistic employee some insight into whether disclosure will be beneficial. Employees may also involve HR personnel to explore their options for how and when to disclose. However, employees may also choose to seek outside help from organisations, such as AS Mentoring and the National Autistic Society, that can provide advice on disclosure and the protections afforded to disabled individuals in workplaces.

While we feel that the data offer important insights into outcomes of disclosure, we also acknowledge that our study has certain limitations. First, our study employed qualitative methods which means we are unable to draw conclusions about causation. Though we propose that the factors outlined above may predict the outcomes of disclosure, we recommend that future studies employ quantitative methods with a much larger sample of participants in order to establish these causal relationships. Second, the sample of autistic people who took part in this research was fairly small (N = 24), and was predominantly White (n = 22, 91.6%). Although approximately 38% of autistic individuals have a co-occurring intellectual impairment (Center for Autism Research, 2016), this study only offers insight into the experiences of autistic individuals without an intellectual disability (ID). It may be that autistic individuals with ID have different employment and disclosure experiences. Research has shown that autistic adults with a co-occurring intellectual impairment have more difficulty finding and maintaining employment (Bush & Tassé, 2017). However, there is also evidence that those without ID are more likely to be malemployed (i.e., doing a job not consistent with their skills and abilities) or underemployed (i.e., doing a job for which they are overqualified) (Baldwin et al., 2014). As such, our participants may not represent the wider autistic population in the UK, which makes it difficult to generalise our results. Third, we also lacked equal representation between those who disclosed and those who had not disclosed to anyone in the workplace. This was expected, as the nature of the research tends to attract people who are more open about their autism diagnoses. It limits, however, the conclusions that can be drawn about the motivations behind deciding to avoid disclosing a diagnosis of autism in the workplace.

Despite these limitations, we believe that our research offers an important step towards helping employers and autistic employees understand the factors associated with better disclosure outcomes. These results have implications for improving both individual and organisational practices. Our findings bridge the gap between the act of disclosure and its possible consequences, which can lessen the uncertainty surrounding the decision to disclose for autistic people. Through these results, we hope that autistic people will be able to make an informed decision with less difficulty, ultimately resulting in better employment experiences.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-dli-10.1177_23969415211022955 for Autistic adults’ experiences of diagnostic disclosure in the workplace: Decision-making and factors associated with outcomes by Anna Melissa Romualdez, Zachary Walker and Anna Remington in Autism & Developmental Language Impairments

Footnotes

Author’s note: We have chosen to use identity-first (e.g., autistic individual rather than individual with autism) language throughout this paper, as this reflects the preferences of many members of the UK autistic community, their families, and other stakeholders (Kenny et al., 2016).

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Anna Melissa Romualdez https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6008-845X

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Anna Melissa Romualdez, Centre for Research in Autism and Education (CRAE), UCL Institute of Education, University College London, London, UK.

Zachary Walker, Department of Psychology and Human Development, UCL Institute of Education, University College London, London, UK.

References

- Ameri M., Schur L., Adya M., Bentley F. S., McKay P., Kruse D. (2018). The disability employment puzzle: A field experiment on employer hiring behavior. ILR Review, 71, 329–364. DOI: 10.1177/0019793917717474 [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed).

- Baanders A. N., Andries F., Rijken P. M., Dekker J. (2001). Workplace adjustments among the chronically ill. Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 24, 7–14. DOI: 10.1097/00004356-200103000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin S., Costley D. (2016). The experiences and needs of female adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 20, 483–495. DOI: 10.1177/1362361315590805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin S., Costley D., Warren A. (2014). Employment activities and experiences of adults with high-functioning autism and Asperger’s disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 2440–2449. DOI: 10.1007/s10803-014-2112-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett K., Dukes C. (2013). Employment instruction for secondary students with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review of the literature. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 48, 67–75. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23879887 [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11, 589–597. 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruyere S. M., Erickson W. A., Ferrentino J. T. (2003). Identity and disability in the workplace. William & Mary Law Review, 44, 1173. Retrieved from: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A99988967/AONE?u=ucl_ttda&sid=AONE&xid=137c9c11 [Google Scholar]

- Bublitz D. J., Fitzgerald K., Alarcon M., D’Onofrio J., Gillespie-Lynch K. (2017). Verbal behaviors during employment interviews of college students with and without ASD. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 47, 79–92. DOI: 10.3233/JVR-170884 [Google Scholar]

- Bush, Kelsey L., & Tassé, Marc J. (2017). Employment and choice-making for adults with intellectual disability, autism, and down syndrome. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 65, 23--34. DOI: https://10.1016/j.ridd.2017.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cage E., Troxell-Whitman Z. (2019). Understanding the reasons, contexts and costs of camouflaging for autistic adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49, 1899–1911. DOI: 10.1007/s10803-018-03878-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cage E., Troxell-Whitman Z. (2020). Understanding the relationships between autistic identity, disclosure, and camouflaging. Autism in Adulthood, 2, 334–338. 10.1089/aut.2020.0016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Autism Research. (2016). Intellectual disability and ASD. CAR Autism Roadmap. Retrieved from https://carautismroadmap.org/intellectual-disability-and-asd

- Charmaz K. (2010). Disclosing illness and disability in the workplace. Journal of International Education in Business, 3(1/2), 6–19. DOI: 10.1108/18363261011106858 [Google Scholar]

- Chaudoir S. R., Fisher J. D. (2010). The disclosure processes model. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 236–256. DOI: 10.1037/a0018193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd S. (2005). Understanding autism. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Flower R., Dickens L., Hedley D. (2019). Barriers to employment for individuals with autism spectrum disorder: Perceptions of autistic and non-autistic job candidates during a simulated job interview. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 63, 652. [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P., Alcock J., Burkin C. (2005). An 8 year follow-up of a specialist supported employment service for high-ability adults with autism or Asperger syndrome. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 9, 533–549. DOI: 10.1177/1362361305057871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull L., Lai M.-C., Baron-Cohen S., Allison C., Smith P., Petrides K. V., Mandy W. (2019). Gender differences in self-reported camouflaging in autistic and non-autistic adults. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 24(2), 352–363. DOI: 10.1177/1362361319864804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull L., Petrides K. V., Allison C., Smith P., Baron-Cohen S., Lai M.-C., Mandy W. (2017). “ Putting on my best normal”: Social camouflaging in adults with autism spectrum conditions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 2519–2534. DOI: 10.1007/s10803-017-3166-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T., Joshi A. (2014). Disclosure on the autism spectrum: Understanding disclosure among employees on the autism spectrum. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 7, 278–281. 10.1111/iops.12149 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny L., Hattersley C., Molins B., Buckley C., Povey C., Pellicano E. (2016). Which terms should be used to describe autism? Perspectives from the UK autism community. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 20, 442–462. 10.1177/1362361315588200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay S., Cagliostro E., Leck J., Shen W., Stinson J. (2019). Disclosure and workplace accommodations for people with autism: A systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation, 41, 1914–1924. 10.1080/09638288.2019.1635658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon C. M., Henry S., Linthicum M. (2020). Employability in autism spectrum disorder (ASD): Job candidate’s diagnostic disclosure and ASD characteristics and employer’s ASD knowledge and social desirability. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 27, 142–157. 10.1037/xap0000282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B., Cozzarelli C., Sciacchitano A. M., Cooper M. L., Testa M., Mueller P. M. (1990). Perceived social support, self-efficacy, and adjustment to abortion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 452–463. DOI: 10.1037/0022-3514.59.3.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawhood L., Howlin P. (1999). The outcome of a supported employment scheme for high-functioning adults with autism or Asperger syndrome. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 3, 229–254. 10.1177/1362361399003003003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan L., Leatzow A., Clark S., Siller M. (2014). Interview skills for adults with autism spectrum disorder: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 2290–2300. 10.1007/s10803-014-2100-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris M., Begel A., Wiedermann B. (2015). (Eds.) Understanding the challenges faced by neurodiverse software engineering employees: Towards a more inclusive and productive technical workforce. Proceedings of the 17th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers & Accessibility, (pp. 173--184). [Google Scholar]

- Morrison K. E., DeBrabander K. M., Faso D. J., Sasson N. J. (2019). Variability in first impressions of autistic adults made by neurotypical raters is driven more by characteristics of the rater than by characteristics of autistic adults. Autism, 23, 1817–1829. DOI: 10.1177/1362361318824104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Autistic Society. (2016). The employment gap.

- QSR. (2018). NVivo 12 Pro. QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 12. [Computer software]. Available at: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- Remington A., Pellicano E. (2019). ‘Sometimes you just need someone to take a chance on you’: An internship programme for autistic graduates at deutsche bank, UK. Journal of Management & Organization, 25, 516–534. DOI:10.1017/jmo.2018.66 [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez R. R., Kelly A. E. (2006). Health effects of disclosing secrets to imagined accepting versus nonaccepting confidants. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 25, 1023–1047. DOI: 10.1521/jscp.2006.25.9.1023 [Google Scholar]

- Romualdez A. M., Heasman B., Walker Z., Davies J., Remington A. (2020). “ People might understand me better”: Diagnostic disclosure experiences of autistic individuals in the workplace. Autism in Adulthood. Ahead-of-Print Online Publication. 10.1089/aut.2020.0063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roux A. M., Shattuck P. T., Cooper B. P., Anderson K. A., Wagner M., Narendorf S. C. (2013). Postsecondary employment experiences among young adults with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52, 931–939. 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarrett J. (2017). Interviews, disclosures, and misperceptions: Autistic adults’ perspectives on employment-related challenges. Disability Studies Quarterly, 37. DOI: 10.18061/dsq.v37i2.5524 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sasson N. J., Morrison K. E. (2017). First impressions of adults with autism improve with diagnostic disclosure and increased autism knowledge of peers. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 23, 50–59. 10.1177/1362361317729526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schein E. (2017). Organizational culture and leadership/Edgar H. Schein with peter Schein (5th ed.). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Schneid I., Raz A. E. (2020). The mask of autism: Social camouflaging and impression management as coping/normalization from the perspectives of autistic adults. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 248, 112826. DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuck R. K., Flores R. E., Fung L. K. (2019). Brief report: Sex/gender differences in symptomology and camouflaging in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49, 2597–2604. DOI: 10.1007/s10803-019-03998-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. J., Ginger E. J., Wright K., Wright M. A., Taylor J. L., Humm L. B., Olsen D. E., Bell M. D., Fleming M. F. (2014). Virtual reality job interview training in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 2450–2463. 10.1007/s10803-014-2113-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperry L. A., Mesibov G. B. (2005). Perceptions of social challenges of adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 9, 362–376. 10.1177/1362361305056077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone D. L., Colella A. (1996). A model of factors affecting the treatment of disabled individuals in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 21, 352–401. DOI: 10.2307/258666 [Google Scholar]

- Strickland D. C., Coles C. D., Southern L. B. (2013). JobTIPS: A transition to employment program for individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 2472–2483. DOI: 10.1007/s10803-013-1800-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilczynski S. M., Trammell B., Clarke L. S. (2013). Improving employment outcomes among adolescents and adults on the autism spectrum. Psychology in the Schools, 50, 876–887. 10.1002/pits.21718. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wood-Downie H., Wong B., Kovshoff H., Mandy W., Hull L., Hadwin J. A. (2021). Sex/gender differences in camouflaging in children and adolescents with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51, 1353–1364. DOI: 10.1007/s10803-020-04615-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-dli-10.1177_23969415211022955 for Autistic adults’ experiences of diagnostic disclosure in the workplace: Decision-making and factors associated with outcomes by Anna Melissa Romualdez, Zachary Walker and Anna Remington in Autism & Developmental Language Impairments