Abstract

Radiation-induced proctitis (RIP) is a debilitating adverse event that occurs commonly during lower abdominal radiotherapy. The lack of prophylactic treatment strategies leads to diminished patient quality of life, disruption of radiotherapy schedules, and limitation of radiotherapy efficacy due to dose-limiting toxicities. Semisynthetic glycosaminoglycan ethers (SAGE) demonstrate protective effects from RIP. However, low residence time in the rectal tissue limits their utility. We investigated controlled delivery of GM-0111, a SAGE analogue with demonstrated efficacy against RIP, using a series of temperature-responsive polymers to compare how distinct phase change behaviors, mechanical properties and release kinetics influence rectal bioaccumulation. Poly(lactic acid)-co-(glycolic acid)-block-poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(lactic acid)-co-(glycolic acid) copolymers underwent macroscopic phase separation, expelling >50% of drug during gelation. Poloxamer compositions released GM-0111 cargo within 1 hour, while silk-elastinlike copolymers (SELPs) enabled controlled release over a period of 12 hours. Bioaccumulation was evaluated using fluorescence imaging and confocal microscopy. SELP-415K, a SELP analogue with 4 silk units, 15 elastin units, and one elastin unit with lysine residues in the monomer repeats, resulted in the highest rectal bioaccumulation. SELP-415K GM-0111 compositions were then used to provide localized protection from radiation induced tissue damage in a murine model of RIP. Rectal delivery of SAGE using SELP-415K significantly reduced behavioral pain responses, and reduced animal mass loss compared to irradiated controls or treatment with traditional delivery approaches. Histological scoring showed RIP injury was ameliorated for animals treated with GM-0111 delivered by SELP-415K. The enhanced bioaccumulation provided by thermoresponsive SELPs via a liquid to semisolid transition improved rectal delivery of GM-0111 to mice and radioprotection in a RIP model.

Keywords: Silk-elastinlike protein polymer, Semisynthetic glycosaminoglycan ether, radiation-induced proctitis, rectal drug delivery, hydrogels

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Radiotherapy is a common treatment for lower abdominal cancers, including prostate, ovarian, cervical, bladder, and colonic cancers. More than 300,000 patients receive radiotherapy for lower abdominal malignancies annually, and many will develop radiation-induced proctitis (RIP), a radiotoxic, inflammatory injury of the rectum[1,2]. An estimated 30–75% of all patients will develop acute RIP, up to 20% will develop chronic RIP, and 5% of all patients are at risk for developing more debilitating disorders including fistulas, rectal/anal stenosis, and/or fecal incontinence[1,3]. Patients with acute RIP typically present with symptoms of lower abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, fecal urgency, and diarrhea[1]. Patients that develop chronic symptoms have persistent and more severe symptomology along with increased occurrences of severe bleeding, perforations, intestinal obstructions, strictures, and increased risk of other debilitating conditions (anemia, sepsis, fistulas)[4–6]. Most radiotherapy patients experience an undisclosed loss in quality of life both during and after their treatment. New therapeutic strategies are needed to preserve the quality of life of these patients.

Radiotoxicity and RIP remain prevalent despite advances in administration of radiotherapy, including supine positioning, intensity modulation, image guidance, conformal radiation, and endorectal balloons. Acute presentation of RIP is typically self-managed and, in many cases, causes cessation or alteration of radiotherapy schedules[4]. Endoscopic laser ablation and surgical intervention is reserved for the most severe presentations of RIP. Surgical associated morbidity occurs in 30–65% of instances and postoperative mortality is estimated at 6–25% [3,7–12]. Pharmacological treatments include, but are not limited to sucralfate[13–15], 5-aminosalicylic acid[16], balsalazide[17], Vitamin E[18], Vitamin C[18], steroids[15], formalin[19–21], sodium butyrate[22], pentoxifylline[23], rebamipide[24], Vitamin A[25], short chain fatty acids[26], estrogen/progesterone[27], sodium pentosan polysulphate[28], and misoprostol[29]. While some of these approaches have shown beneficial outcomes, the effects are only moderate and reactionary. None of these treatments, with the exception of sucralfate, are regarded as current practice[6,23,27,30–32]. However, preventative strategies utilizing sucralfate have failed to show differences when compared to placebo treatments in late stage clinical trials, in some cases increasing occurrences of diarrhea and rectal bleeding[14,32,33]. Current management strategies focus on treating pathophysiology and symptomology only once presented. Preventative measures are largely underexplored with small double-blinded trials of misoprostol or sucralfate failing to have an effect[4,32,34–36]. Management strategies to address and prevent the development of acute and subsequent progression to chronic RIP are needed.

Previously our lab explored the use of a semi-synthetic glycosaminoglycan ether (SAGE) to prevent RIP[37]. SAGEs are modified glycosaminoglycans, containing inherent biological properties enhanced and altered through chemical modification. One such SAGE, GM-0111 (Figure 1A), is the product of hyaluronic acid digestion and chemical sulfation[38]. GM-0111 has been used to treat a variety of mucosal inflammatory diseases, including RIP, interstitial cystitis, and periodontitis[37–40]. GM-0111 is considered as a broad anti-inflammatory agent, with many purported mechanisms of action ranging from ligand blocking, barrier formation, minimization of immune cell migration, reducing cytokine release, inhibition of mast cell infiltration into inflamed tissues, and inhibition of bacterial growth[38,40,41]. GM-0111 in combination with a recombinant thermoresponsive silk-elastinlike protein polymer (SELP) was shown to prophylactically protect mice from RIP [37]. Utilizing the transition from a liquid state to a semisolid gel, SELPs improved rectal delivery and increased GM-0111’s therapeutic effects.

Figure 1: Structures of therapeutic and polymers used in this study.

A) Structure of the semisynthetic glycosaminoglycan ether, GM-0111. B) & C) Schematics of silk-elastinlike protein polymers 815K and 415K. Red and blue motifs represent silk and elastin portions, respectively. SELP-815K contains repeats of 8 silk units, 15 elastin units, and one lysine substituted elastin unit. SELP-415K contains repeats of 4 silk units, 15 elastin units, and one lysine substituted elastin unit. Silk motifs hydrogen bond to form beta sheets. Elastin units provide elasticity and form a porous structure. One lysine unit occurs in every 15 elastin blocks giving the overall polymer a net positive charge at pH 7.4. D) Structure of Poloxamer 407. E) Structure of poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide)-block-(poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide).

The recombinant nature of SELPs allows for precise genetic tuning of structure and resulting function. The combination of Bombyx mori silk (Gly-Ala-Gly-Ala-Gly-Ser) with human tropoelastin (Val-Pro-Gly-Val-Gly) provides polymer strength and thermoresponsivity, respectively[42]. A wide variation of mechanical, structural, and functional properties can be achieved through variation of the silk to elastin motif ratio[43]. For instance, SELP-815K (8 silk, 15 elastin, 1 lysine substituted elastin motif) has a higher stiffness than SELP-415K (4 silk, 15 elastin, 1 lysine substituted elastin motif), due to a higher silk to elastin ratio (Figure 1B, 1C)[44,45]. Additional commercially available polymers, such as Poloxamer 407 (Figure 1D) and poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide)-block-(poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(D,L-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA-PEG-PLGA) (Figure 1E) have also served as rectal delivery systems and used in the clinic[46–49]. SELPs undergo sol to gel transitions by hydrogen bonding and subsequent formation of β-sheets between intermolecular silk blocks, while Poloxamers and PLGA-PEG-PLGA utilize entanglement of micelles and Van der Waals interactions for formation of gel structures. Based on previous success in prophylactically treating RIP, in this study we performed systematic correlation of polymer structure with function in SAGE delivery to inform the appropriate selection of polymer formulations for rectal delivery of SAGE in the treatment of RIP. We hypothesized that primary polymer structure, varying mechanical properties, and ultimate gel architecture will result in differences in GM-0111 rectal bioaccumulation and protection by employing a RIP animal model. In this manuscript, we compare how variation of polymer structures (Figure 1, B–E) influences rectal bioaccumulation and efficacy of GM-0111 (Figure 1A).

Materials and Methods

Materials

GM-0111 was purchased from GlycoMira Therapeutics, Inc. (Salt Lake City, UT). Poloxamer 407 was purchased from Spectrum Chemical Mfg. Corp. (New Brunswick, NJ). Poly(lactic acid)-co-(glycolic acid)-block-poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(lactic acid)-co-(glycolic acid) (PLGA-PEG-PLGA) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). CF™633 was purchased from Biotium (Fremont, CA). SELP-815K and SELP-415K were produced and characterized as previously described[45,50–52]. Post purification shear processing was performed on SELPs to normalize and enhance material properties[51].

Macroscopic Phase Separation

Prior to testing all polymer formulations were prepared fresh. Poloxamer 407 and PLGA-PEG-PLGA were solubilized in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to 10 and 20 wt% solutions with GM-0111 (100 mg/mL). Sheared SELP-815K and −415K 12 wt% were mixed with GM-0111 in PBS, yielding 11 and 4 wt% polymer solutions with 100 mg/mL GM-0111. Formulations were distributed into scintillation vials and sealed. They were then immersed in a 37 °C water bath. At various timepoints macroscopic phase separation was observed by horizontally tilting the vial and observing separated fluid. Solutions exhibiting gelation and phase separation were then replicated at smaller volumes (100 μL), and the mass of GM-0111 unloaded was quantified using an Azure A colorimetric assay. Briefly, 10 μL of GM-0111 sample were mixed with 190 μL of a 0.025 mg/mL Azure A solution. Absorbance was observed at 650 nm on a SpectraMax M2 spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Calibration curves were utilized with every sample reading to experimentally derive concentrations of GM-0111.

Rheology

Prior to testing all polymer formulations (Poloxamer 407 20 wt%; SELP-815K 11 wt%; SELP-415K 11 wt%) were freshly prepared with GM-0111 (100 mg/mL). Rheological testing was performed on a Malvern Kinexus Ultra+ Rheometer (Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, United Kingdom) with a 2°, 20 mm steel cone. The environment was kept humidified using an environmental chamber. Viscosity was measured using an oscillatory test over temperatures 4–37 °C (5.76 °C/min) at an angular frequency of 6.283 rad/s. This was followed by a 3-hour oscillatory sweep at 37 °C, 0.01% strain, and 6.283 rad/s. Storage (G′) and loss (G″) moduli were monitored throughout. Conditions of gelation were defined as the crossover point between storage and loss moduli. All rheology experiments were conducted in at least triplicate.

In Vitro Release

Prior to testing, all polymer formulations (Poloxamer 407 20 wt%; SELP-815K 11 wt%; SELP-415K 11 wt%) were freshly prepared with GM-0111 (100 mg/mL). Release rates were investigated in vitro using previous methodology[37]. Briefly, polymers and GM-0111 were mixed yielding a 100 mg/mL final concentration of GM-0111. Immediately following, each formulation was loaded into a tuberculin syringe, sealed with Parafilm, and allowed to gel in a humidified incubator at 37°C overnight. The next day a razor blade was used to cleave the needle end of the syringe, producing a uniform cylindrical geometry. Gel formulation was then extruded using the plunger and cut into 20 μL discs. Each disc was placed in an Eppendorf tube and massed for normalization. Then 1 mL of simulated intestinal fluid was added to each tube. At various timepoints (5 min., 15 min., 30 min., 1 hr., 3 hrs., 6 hrs., 12 hrs.) 100 μL of release media was collected and replaced. This was stored at 4°C until evaluated using an Azure A colorimetric assay.

In vivo accumulation

GM-0111 was fluorescently labeled as previously described[40,41]. Briefly, 800 mg of GM-0111, 126 mg of N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N’-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC), and 113 mg of N-hydroxysuccinimide, were suspended in 20 mL of water. This solution was stirred at room temperature for 15 minutes. CF633 (9 mg) was thawed, solubilized in 0.9 mL of water, and added to the reaction. The reaction proceeded overnight before dialysis to remove remaining starting materials and the final product was lyophilized (633GM-0111). In all steps, care was taken to protect sensitive materials from light.

BDF-1 mice (7–9 weeks, Strain: 099, 50% male, 50% female) (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) were purchased and allowed to acclimate for one week. Two days prior to experimentation mouse diet was switched to AIN-76A (Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ), an alfalfa free feed with the goal to limit tissue autofluorescence. The night prior to experimentation food and bedding were removed to fast mice and empty digestive tract. Following this, experimentation proceeded, and the alfalfa free diet continued. Formulations were prepared on ice immediately prior to testing by mixing 2-parts GM-0111 and 1-part 633GM-0111 with thermoresponsive polymers (Poloxamer 407 20 wt%; SELP-815K 11 wt%; SELP-415K 11 wt%). Animals were then anesthetized using 3% isoflurane and instilled as previously described (n=10)[37]. Each animal received approximately 100 μL of the appropriate formulations. At various timepoints (6 hrs., 12 hrs., 24 hrs., 48 hrs.,) animals were sacrificed and rectums collected. The rectums were then cut down the longitudinal axis to expose the inner lumen. This tissue was then pinned down on a foam backing and imaged using a Spectrum In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS) (Caliper Life Sciences, MA). Tissues were then fixed overnight in 4% neutral buffered formalin at 4°C followed by storage in 70% ethanol. Sectioning was performed by ARUP (Salt Lake City, UT) for a tissue thickness of 2 μm. Tissues were then mounted with ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant with DAPI (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and imaged using a Nikon A1 confocal microscope. Images obtained from IVIS were quantified for a radiant efficiency using Living Image Software (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). Acquired confocal images were analyzed via ImageJ. Semiquantitative analysis was performed by normalizing fluorescent signaling to tissue area using DAPI staining.

In vivo efficacy

BDF-1 female mice (7 weeks, Stock no. 100006) (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were purchased and allowed to acclimate for at least one week. The night prior to experimentation mice were massed and fasted by removing food and bedding. Animals were assigned into groups at random, anesthetized, and subsequently instilled with 100 μL of appropriated formulation. This followed established methodology as described[37]. Immediately following rectal administration, anesthetized mice were transferred to a wood plate in a supine position. Targeted irradiation to the lower abdominal area was applied utilizing 1 × 4 cm2 aperture, with the remainder of the mouse protected by 16.35 mm thick lead plate. A total radio dose of 37.12 ± 0.95 Gy was achieved using a RS 2000 X-ray irradiator (RAD SOURCE Technologies, GA, USA) set to level 4 for 716 s. Following this procedure, mice were monitored during recovery and returned to cages with feed. Mice were sacrificed and tissue collected 7 days following treatment and irradiation. All animal study protocols in this manuscript were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Utah.

Pain assessment

Behavioral pain was evaluated immediately prior to fasting and prior to sacrifice on day 7. Briefly, mice were placed in an enclosure with a mesh bottom and allowed to acclimate for no less than 10 minutes. The degree of pain in the lower abdominal area was assessed with von Frey filaments of varying stiffnesses (0.04, 0.16, 0.40, 1.00, and 4.00 g). The lower abdominal area was stimulated ten times with each stiffness and positive responses (sharp abdominal retraction, jumping, or licking/scratching of stimulated area) were recorded[37,53].

Tissue collection and histological assessment

Following animal sacrifice, 1 – 2 cm sections of the rectum were necropsied and placed in 4% neutral buffered formalin overnight at 4 °C for fixation. Tissue was then transferred to a 70% ethanol solution and submitted to the ARUP core facility for processing and embedded in paraffin blocks. 2 μm sections were obtained, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin stain. Slides were analyzed microscopically and representative images were obtained using an Olympus U-MDOB3 with an Olympus DP27 camera. Histological scoring was performed to assess for surface cell flattening, luminal migration of nuclei, cryptitis, edema, inflammation in the surface epithelium and within the lamina propria, eosinophilic crypt abscesses, loss of glands, and loss of goblet cells as previously described[54,55]. A corresponding overall histologic grade was assigned based on the severity of identified mucosal damage including crypt atrophy and crypt loss and assigned as follows: normal (grade 0), mild (grade 1), moderate (grade 2), marked (grade 3), and severe (grade 4). Analysis was performed in a blinded fashion as the pathologist was unaware of assigned treatment group at the time of evaluation.

Statistical Analysis

A Grubb’s test was used for assessment of outliers within data sets. A two-way, unpaired student’s t-test was used to assess statistical significance between experimental and control groups. A two-way ANOVA was utilized to determine significance of data comparing more than two groups. Bonferroni post-tests assigned significance between specific groups. Graphs and charts were created in GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc. La Jolla, CA) and were edited in Adobe Illustrator (Adobe, San Jose, CA). All data are represented as a mean ± standard deviation, with the exception of computed area under the curve represented as mean ± propagated error. Significance was assigned as p ≤ 0.05 (*), p ≤ 0.01 (**), or p ≤ 0.001 (***).

Results

Macroscopic Phase Separation

To evaluate thermoresponsive behavior of polymers for uniform rectal delivery, we evaluated gels for formation and homogeneity. The PLGA-PEG-PLGA (10 and 20 wt %) compositions resulted in macroscopic phase separation (Figure S1A). This separation was collected and the percentage of unloaded GM-0111 was calculated to be 76.30 ± 2.09 % and 54.77 ± 34.29% for 10 and 20 wt% matrices, respectively (Figure S1B). Macroscopic phase separation of PLGA-PEG-PLGA copolymers exhibited a large degree of GM-0111 unloading upon gelation and were deemed unsuitable for further investigation. The addition of GM-0111 to low wt % Poloxamer 407 and SELP-415K solutions resulted in non-gelling solutions. All other formulations formed an observable gel within one hour. SELP-815K (4 and 11 wt %), SELP-415K (11 wt %), and Poloxamer 407 (20 wt %) did not result in macroscopic phase separation. The macroscopic separation exhibited by PLGA-PEG-PLGA formulations and subsequent GM-0111 retention may have led to nonuniform coating of the rectum lumen.

Rheological Analyses of Control Polymers and Polymers Formulated with GM-0111

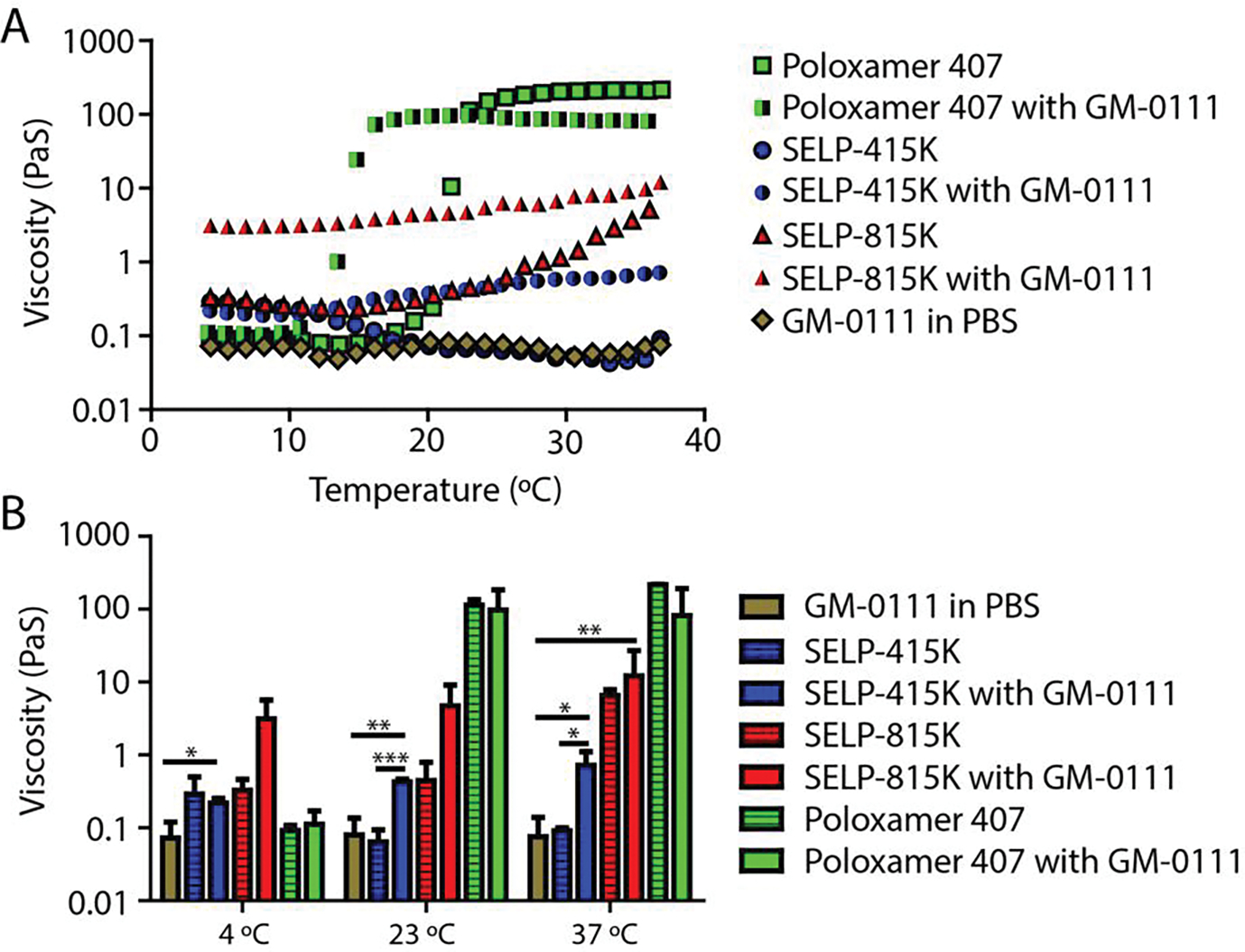

Rheological evaluation of each formulation was conducted to determine if they would be injectable within the clinical environment. To determine aspects of injectability, gelation kinetics, and potential drug-polymer interactions, rheological experiments were performed. For formulations that produced gels within one hour and no indications of macroscopic phase separation, we evaluated the viscosity from 4–37 °C to determine injectability (Figure 2A). Viscosities were then analyzed at 4 °C, 23 °C, 37 °C, representing refrigeration, ambient, and body temperatures (Figure 2B). A clear shift in the thickening temperature of Poloxamer 407 can be observed when GM-0111 is incorporated (Figure 2A). At 23 °C, the Poloxamer composition became too viscous to enable rectal delivery. Incorporation of GM-0111 into Poloxamer 407 did not result in significant changes in viscosity at the analyzed temperatures. However, SELP-415K with GM-0111 became significantly more viscous than GM-0111 in PBS at all analyzed temperatures (p <0.05). Upon GM-0111 addition, the viscosity of SELP-415K increased from 0.064 ± 0.026 PaS to 0.423 ± 0.042 PaS (p < 0.001) at 23 °C and from 0.090 ± 0.009 PaS to 0.720 ± 0.389 PaS (p = 0.049) at 37 °C. Increased viscosity due to the addition of GM-0111 to SELPs was more than simply additive, indicating intermolecular interactions between SELP and GM-0111. Poloxamer/GM-0111 interactions were not as apparent. SELP-415K and SELP-815K formulations reached respective maximum viscosities of 0.72 ± 0.39 PaS and 12.015 ± 14.912 PaS at 37 °C. However, all formulations had viscosities at 4 °C that would allow them to be administered through standard clinical approaches for rectal delivery.

Figure 2: Viscosity of candidate formulations.

A) Viscosity trace of control polymers and polymers formulated with GM-0111 (100 mg/mL). B) Viscosity values at various temperatures of control polymers and polymers formulated with GM-0111 (100 mg/mL) (*:p<0.05, **:p<0.01, ***:p<0.001).

To monitor the sol to gel transition of polymers alone and polymer/GM-0111 formulations, we conducted a 3-hour oscillatory time sweep (Figure 3A). At specific timepoints, 1, 5, 30, and 180 minutes, we quantified the storage modulus, also known as the elastic modulus (Figure 3B), for statistical analysis. The incorporation of GM-0111 in SELP-415K significantly increased the storage modulus from 0.81 ± 0.43 Pa to 8.51 ± 3.77 Pa after 5 minutes (p = 0.024) and from 137.58 ± 50.88 Pa to 1890.00 ± 840.54 Pa after 30 minutes (p = 0.022). The increased storage modulus of SELP-415K/GM-0111 formulations at early timepoints suggests a hygroscopic property of GM-0111, which would dehydrate polymer strands, increasing effective concentration. Interestingly, the addition of GM-0111 to SELP-815K significantly decreased the storage modulus, at timepoints after its gelation time (Figure 2C), from 136.50 ± 10.57 kPa to 35.42 ± 20.33 kPa after 30 minutes (p = 0.001) and from 302.60 ± 23.72 kPa to 46.64 ± 26.32 kPa after 180 minutes (p < 0.001). GM-0111 interaction with SELP-815K may interrupt the formation of longer silk blocks, decreasing the storage modulus. The increased storage modulus of the SELP-815K/GM-0111 formulation is also observed at 1 minute, reinforcing the possible hygroscopic property of GM-0111. Poloxamer 407/GM-0111 storage modulus was significantly lower than Poloxamer 407 alone after 180 minutes (p < 0.001), exhibiting a gradual decrease in modulus over the three-hour measuring period (Figure 3A). This indicates that GM-0111 interfered with the formation of the micellar network in poloxamer gels. Incorporation of GM-0111 significantly slowed the gelation time of Poloxamer 407 from near instantaneous (3.33 ± 2.88 s) gelation up to several minutes (186.67 ± 319.00 s) (Figure 3C). SELP-815K and SELP-815K/GM-0111 gelation times were not statistically different. SELP-415K/GM-0111 formulations formed a gel significantly faster (330.00 ± 18.03 s) than the SELP-415K polymer only (636 ± 132.88 s). Additionally, the SELP-415K/GM-0111 composition underwent gelation significantly more slowly than Poloxamer/GM-0111 (p = 0.006) and SELP-815K/GM-0111 (p = 0.036). Inclusion of GM-0111 alters the rate of gel formation and final gel strengths, indicating modification of network formation likely due to existing polymer-drug and drug-solvent interactions.

Figure 3: Storage moduli and gelation behavior of candidate formulations.

A) Storage moduli trace of control polymers and polymers formulated with GM-0111 (100 mg/mL). B) Storage moduli after 1 min., 5 min., 30 min., and 3 hrs. of testing. (*:p<0.05, **:p<0.01, ***:p<0.001) C) Gelation time of control polymers and polymers formulated with GM-0111 (100 mg/mL) (*:p<0.05, **:p<0.01, ***:p<0.001)

In Vitro Release

Rectal delivery must be carefully balanced for locally active therapeutics to deliver their payload prior to defecation yet provide prolonged delivery to maximize therapeutic effect. In vitro testing was performed using gels produced from Poloxamer 407 20 wt%, SELP-815K 11 wt%, and SELP-415K 11 wt%, all with 100 mg/mL GM-0111 (Figure 4A). Analysis of the initiating one hour of release revealed significant differences among Poloxamer and SELP formulations (Figure 4B). Poloxamer 407 gels released 7.89 ± 1.92% of GM-0111 cargo after 5 minutes, completing cumulative release within 1 hour. SELP-815K and SELP-415K gels resulted in similar release kinetics with respective release of 1.55 ± 2.12% and 4.3 ± 3.95% after 5 minutes. SELP gels resulted in sustained release for 12 hours in vitro. Compared to SELP gels, Poloxamer gels released GM-0111 significantly faster after 15, 30, and 60 minutes of release (p < 0.001) (Figure 4B). There were no statistical differences between SELP-815K and SELP-415K formulations. This similarity suggests a pore mediated release mechanism, likely dominated by the length of elastin domains. SELP gels provided a controlled release profile over a 12-hour period, compared to only 1 hour for Poloxamer. The sustained release of SELP matrices may provide an increased duration of therapeutic window, as rapid mucosal turnover clears accumulated GM-0111 promptly.

Fig. 4.

Controlled release of glycosaminoglycan. A) Release kinetics of GM-0111 (100 mg/mL) from poloxamer 407, SELP-815K, and SELP-415K. B) Burst release quantified at various times (***: p < 0.001).

GM-0111 Bioaccumulation in the Rectum of BDF-1 Mice

To understand how formulations impacted local bioaccumulation in the rectum we used an In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS) to observe the luminal surface excised rectal tissue (Figure 5A) and confocal microscopy. During testing all formulations were easily capable of being administered through 0.51 mm diameter (1.5 Fr) catheters. Macroscopic evaluation via an IVIS showed semi-quantitative enhancement of accumulation in rectal tissue with all polymeric groups (Figure 5B). Bioaccumulation persisted past 24 hours following rectal administration, especially within the SELP-415K and Poloxamer 407 groups. After 6 hours of administration, SELP-415K copolymers resulted in significantly higher degrees of GM-0111 accumulation when compared to all other experimental groups (7.393 × 107 ± 6.427 × 107 p/sec/cm2/sr; p < 0.001) (Figure 5C). Poloxamer 407 (4.587 × 107 ± 3.159 × 107 p/sec/cm2/sr) resulted in significantly higher accumulation compared to the PBS (1.425 × 107 ± 8.179 × 106 p/sec/cm2/sr) and SELP-815K (1.637 × 107 ± 6.151 × 106 p/sec/cm2/sr), after 6 hours post administration (p < 0.05). SELP-415K showed the greatest degree of enhancement at the 6-hour time point having 5 times the fluorescent signal as the PBS group and nearly twice as much as the Poloxamer 407. The maximum radiant efficiency for all groups was observed 6 hours following rectal administration (Figure 5D). The area under the curve was then calculated for each polymer composition to determine overall exposure of the tissue to GM-0111 over the study period (Figure 5E). SELP-415K again showed the greatest enhancement of GM-0111 delivery compared to the other compositions evaluated over the studied period. Microscopic evaluation via confocal microscopy (Supplementary Figure 2) confirmed SELP-415K significantly increased GM-0111 accumulation as analyzed, compared to all other groups after 6 hours (p < 0.001) and compared to PBS after 12 hours (p < 0.01) (Figure 6A). After 6 hours, SELP-415K increased the relative fluorescence signal 4.8-, 8.0-, and 82.9-fold compared to Poloxamer 407, SELP-815K, and PBS, respectively. Calculated area under the curve (Figure 6B, 6C) further illustrates the enhancement of utilizing SELP-415K as a polymeric carrier to deliver GM-0111. In both IVIS and confocal analysis, the majority of tissue fluorescence was lost 24 hours after administration, likely resulting from rapid tissue turnover found in the mucosal compartment. SELP-415K retains a larger portion of fluorescence after 12 hours. Confocal analysis revealed absorption into the muscular mucosae, sub mucosa, and even interactions with endothelial cells. The increase of fluorescent signal from SELP-415K matrices could be a factor of improved rectal spreading and sustained release across the mucosal layer. The corroboration between the macroscopic (IVIS) and microscopic (confocal microscopy) analyses led us to proceed with SELP-415K as our polymeric carrier of choice in our subsequent investigations.

Figure 5: Assessment of Rectal Bioaccumulation.

A) Schematic of tissue imaging. Tissue was dissected from sacrificed animals, and rectums were cut down the longitudinal axis. Luminal tissues were then pinned face up and imaged using IVIS. B) Representative images of processed rectums receiving fluorescently labeled GM-0111 via SELP-415K, Poloxamer 407, SELP-815K, of PBS. C) Normalized radiant efficiency of mice receiving respective compositions. (ꝉ: SAGE delivered by 415K bioaccumulate significantly higher than all other compositions (p<0.05); ⱡ: Delivery by Poloxamer 407 results in significantly higher bioaccumulation than SELP-815K and PBS (p,0.05). D) Maximum normalized radiant efficiency occurred at 6 hours. (**: p<0.01; ***:p<0.001). E) Calculated total area under the curve of GM-0111 for each delivery system (**: p<0.01; ***:p<0.001).

Figure 6: Analysis of GM-0111 rectal bioaccumulation via confocal microscopy.

A) Fold increase in tissue fluorescence from polymers delivering fluorescently labeled GM-0111 per tissue area (ꝉ: 415K significantly higher than all other polymers, p<0.001; ⱡ: SELP415K significantly higher than PBS, p<0.01). B) Calculated GM-0111 area under curve (ꝉ: 415K significantly more than all other systems, p<0.01). C) Total calculated area under the curve for polymeric systems delivering GM-0111 (***: p<0.001).

Behavioral Pain Responses

To understand how GM-0111 formulations impacted radiation-induced pain in mice we assessed behavioral pain responses. Irradiated animals (n=6) showed a dramatic increase in their sensitivity to mechanical stimulation (Figure 7A). All animals showed a typical log shaped response increasing stimulation levels. Allodynia, or the sensitization to previously nonpainful stimuli, was assessed by calculating the stimulation level required to increase response rates by 30% from baseline measurements (Figure 7B). Non-irradiated healthy mice (n=5) had no meaningful change in their pain response, indicating that radiation and no other environmental factors were responsible for changes to the pain response. The GM-0111 SELP-415K enema group needed a stimulus threshold of 2.76 ± 1.92 g, exhibiting improved allodynia compared to all other irradiated mice which had stimulus thresholds less than 0.15 g (p<0.001) (Figure 7B). The greatest resolution of behavioral responses was observed at the 0.16 g and 0.40 g stimulus levels (Figure 7C). At these forces, the nonirradiated baseline response rates (n=30) were 16.33 ± 11.8 % and 19.66 ± 10.66 %, respectively. Upon irradiation the animal response rates increased across all groups. The PBS only group had response rates of 70.00 ± 25.29 % and 70.00 ± 17.89 % at 0.16 and 0.40 g stimulus respectively. At the 0.16 g, 0.40 g, and 1.0 g stimuli the nonirradiated baseline had a significantly lower response rate (p < 0.001) than the irradiated PBS, GM-0111 in PBS, and SELP-415K compositions (Figure 7C). Where traditional saline-based rectal delivery of GM-0111 failed to provide meaningful protection to radiation induced pain, delivery from thermoresponsive polymers, particularly SELP-415K, showed improved responses. There was no significant difference between the non-irradiated baseline response rate and SELP-415K GM-0111 composition at stimuli of 0.16 g, 0.40 g, and 1.0 g (p >0.05). The SELP-415K/GM-0111 treatment significantly lowered response rates compared to PBS, GM-0111, and SELP-415K groups at the 0.16 g and 0.40 g stimulus levels (Figure 7C). Behavioral outcomes indicate the necessity of SELP-415K to deliver GM-0111 for a protective capability in this RIP animal model. The retention and increased bioaccumulation afforded by this formulation likely increases rectal bioavailability and more easily achieves a therapeutic window for pain reduction.

Figure 7: Behavioral response rates of irradiated BDF-1 mice.

A) Response rate of BDF-1 mice 7 days following treatment. Mice were assessed with stimulation of 0.04, 0.16, 0.4, 1.0, and 4.0 g filaments to the lower abdomen. B) Threshold of stimulus needed to increase response rate 30% from baseline measurements. (ꝉ: threshold exceeded 4.0 g (***: p <0.001). C) Response rates for 0.16, 0.40, and 1.0 g stimulus (***: p<0.001, *:p<0.05).

Animal Health

The ability of GM-0111 to protect animal health in response to radiation-induced injury was evaluated by measuring animal weight change, fecal mass, and fecal water content. Healthy control mice maintained their initial mass, whereas radiation caused a statistically significant drop in weight (Figure 8A). The irradiated animals receiving the GM-0111 SELP-415K enema maintained 96.98 ± 13.28% of their body weight, similar to the non-irradiated control group (99.84 ± 2.59 %). Mice receiving the GM-0111 SELP-415K composition exhibited significantly better weight maintenance than mice that received no treatment, or GM-0111 in PBS. SELP-415K alone was insufficient to provide any protection. Both SELP-415K and GM-0111 were required in combination to have a meaningful therapeutic effect. During final animal assessment and sacrifice, we collected animal fecal matter for further analysis. The mass of fecal content (Figure 8B) was insignificantly higher in both healthy and irradiated animals receiving GM-0111 SELP-415K. This increase was not associated with a decreased water content in the fecal material (Figure 8C). Together, these data indicate an indirect increase in animal health and that the SELP-415K/GM-0111 formulation did not substantially interfere with voiding.

Figure 8: Assessment of animal mass and fecal matter.

A) Animal mass reported as a percentage of starting mass prior to irradiation. B) Mass of collected feces from animals. C) Percentage of water content in fecal matter of mice (*:p<0.05, **:p<0.01, ***:p<0.001).

Histology

To understand the SELP-415K GM-0111 system’s local radioprotective effects, we performed histological evaluation of rectal tissue. Evidence of radiation-induced damage was identified in irradiated animals (Figure 8A). Sections show variable amounts of inflammation within the lamina propria and surface epithelium along with cryptitis. There was loss of glands (crypt dropout) and goblet cells, eosinophilic crypt abscesses, cell flattening in the surface epithelium, and luminal migration of epithelial nuclei. These findings were comparable with RIP injury histologically as described by Hovdenak et al[54]. Irradiated animals that received PBS alone had distinct pathologic features compared to healthy controls (Supplementary Figure 3) (p < 0.001). Epithelial alterations attributed to irradiation were identified in 21 of 24 samples. All healthy animals (n=5) showed tissue with intact crypts and no significant microscopic alterations. Overall, animals receiving the SELP-415K GM-0111 showed moderate amount of mucosal damage, with all other irradiated groups exhibiting more severe changes. When scored in a blinded manner, SELP-415K GM-0111 reduced cell flattening, luminal migration, gland loss, and goblet cell loss within the rectal tissue (Supplemental Figure 3). Both treatments utilizing GM-0111 recorded histological scorings of 0 for inflammatory infiltrates (Supplemental Figure 3), suggesting that GM-0111 may have an immunomodulatory effect. The overall injury grade was further calculated with the SELP-415K GM-0111 treatment recording the lowest overall grade of injury, compared to all other irradiated groups (Figure 8B). Together these findings indicate a protective effect from delivery of GM-0111 by SELP-415K copolymers.

Discussion

RIP is a debilitating disease and radiotoxic event, in need of effective prophylactic therapeutic strategies. However, current pharmaceutical interventions have been largely ineffective or carry significant side effects that prevent their usage until after symptoms emerge. GM-0111 has prophylactic efficacy in treating radiation induced disease but requires the use of drug delivery technologies to achieve meaningful results in the rectum. Previously, we showed the capability of SELPs to effectively and efficiently enhance delivery of GM-0111 to the rectum for protection in a RIP model[37]. These positive outcomes and advantages of rectal administration (noninvasive nature, localized delivery, limited systemic exposure, natural clearance via defecation, and rapid effect) led us to further investigate other thermoresponsive formulations[56]. In this study, we demonstrated the utility of temperature responsive polymer systems for enhancing rectal delivery of GM-0111 and showed that primary polymer structure and physicochemical properties have dramatic impact on function. Initial compositions were chosen from studied material properties. The concentration of drug chosen was based on careful evaluation of drug/material interactions. Previously, incorporation of less GM-0111 (10 mg/mL) into these polymers yielded compositions with incomplete release by 24 hours[39]. This sustained release likely results from drug-polymer ionic interactions. Increased loading of SELP-815K to 100 mg/mL GM-0111 increased the percent released cargo after 24 hours and maintained mechanical properties sufficient for rectal gelation. We hypothesized this increased GM-0111 concentration would lead to increased bioavailability. All polymeric systems used had injectable viscosities at 4 °C, with thickening, or gelation events following elevation to body temperature after administration. Controlled release from SELP-415K and SELP-815K provided a sustained release profile lasting significantly longer than poloxamer based delivery. Upon rectal administration, GM-0111 delivery via SELP-415K resulted in the highest degree of bioaccumulation. This formulation showed the ability for prophylactic reduction of radiation-induced tissue damage and amelioration of RIP in an animal model. The combination of a thermoresponsive polymer-drug delivery system significantly reduced pain response and substantially ameliorated local radiotoxicity.

Mechanical properties of rectal formulations influence drug bioaccumulation. Typically, administration of liquid enemas allows for rapid absorption due to circumvention of matrix-mediated drug release[57], however these commonly suffer from poor retention time and leakage[58]. The viscosity properties of a liquid enema largely influences the degree of rectal spreading[56], with low viscosity formulations capable of spreading more. Thus, the transition of a phase-changing enema from a liquid to semisolid provides a mechanism to ensure uniform coverage and increased bioaccumulation by improving retention. SELP-415K and SELP-815K obtained similar release kinetics, but the use of SELP-415K drastically increased the bioaccumulation of GM-0111 when compared to SELP-815K. We hypothesize this is due to the decreased gelation rate of SELP-415K, the resulting increased duration of a liquid state may allow for increased penetration of the mucus coating, followed by retention as a semisolid formulation. SELP-815K due to is faster gelation, did not penetrate as deeply into the mucus prior to gelling, resulting in reduced accumulation. Poloxamer 407 also lead to a high amount of GM-0111 accumulation, likely due to its native gel architecture of intertangled micellular arms, non-physical crosslinking through Van der Waals interactions, and highly viscous gel nature[59]. This would lead to luminal spreading due to the slow flow aspects of Poloxamer formulations. Additionally, both Poloxamer and SELP analogs have exhibited mucoadhesive properties[59,60], which also influence rectal spreading[56]. After 6 hours, the 7.9-fold increase in relative fluorescence signal from SELP-815K to SELP-415K illustrates the importance of the liquid to semisolid enema transition. The duration of SELP-415K in the liquid state enhanced bioaccumulation compared to SELP-815K formulations, while the retention provided by semisolid enema formation increased accumulation as seen in an 82.9-fold increase of fluorescence signal compared to the liquid PBS enema. Many formulations utilize Poloxamer to deliver and accumulate therapeutics in the gastrointestinal space[61–64]. Our SELP-415K formulation outperformed the Poloxamer 407 formulation in terms of rectal bioaccumulation of GM-0111. Liquid enemas are commonly employed for rectal drug delivery and have shown efficacy in treating a variety of diseases. Utilization of a thermoresponsive enema, such as SELP-415K, could further improve these treatments with increased retention, bioaccumulation, and rectal or systemic bioavailability.

Upon rectal administration of the selected formulations, GM-0111 must overcome the mucosal barrier to enter the columnar epithelial layer prior to defecation and resulting enema expulsion. Due to this the swift controlled release, Poloxamer 407 (1 hour) and SELPs (12 hours) are advantageous for luminal bioaccumulation. The rectal mucosal barrier has a turnover time of 3–4 hours[56,65]. This turnover time can be affected by disease states and mucoadhesive materials, such as the selected formulations. The sustained release exhibited by SELP-415K is advantageous, as it would span the time of several mucosal turnovers. Additional mucosal-SELP interactions may lengthen this mucosal turnover time[56,60] and, hypothetically, lengthen the duration that the therapeutic window is achieved within patients. A Poloxamer formulation would be cleared in a single mucosal turnover and decrease overall bioavailability. Once the mucosal barrier is crossed, GM-0111 will likely undergo absorption via the paracellular pathway due to its ionicity, water solubility, and relatively larger molecular weight[66], yet this is still to be determined experimentally. Increased accumulation within the rectal epithelium then potentially increases therapeutic effects.

Once absorbed, GM-0111 may exert its immunomodulatory effects locally in the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, or enter systemic circulation[56]. Rectal radiation injury can lead to the breakdown of the protective epithelial layer, progressive endothelial dysfunction, and an inflammatory state resulting from tissue and pathogen associated damages[2,67,68]. Breakdown of the columnar epithelial layer may lead to bacterial invasion from native flora. GM-0111 inhibits growth of gram negative bacteria (Porphyyromonas gingivalis and Aggretgatibacter actinomycetemcomitans) as well as inhibit pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs) such as toll like receptors 2 and 4 (TLR2, TLR4)[41]. TLR-2/4 recognize lipopolysacharrides, lipoproteins, and bacterial toxins which exacerbate radiation damage by entering compromised tissues. Receptor signaling leads to nuclear translocation of nuclear factor kappa beta and subsequent transcription of inflammatory mediators[69,70]. Analogs of GM-0111 have also been shown to block toxicities associated with Clostridium difficile toxin A in colonic epithelium. Clostridium difficile has been classified as one of three “urgent threats” by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States[71]. Additional GM-0111 inhibition of receptor against glycation endproducts, P-selectin, and polymorphonuclear leukocytes can protect from endogenous tissue damage associated molecular patterns that may be associated with radiation challenge[41]. This multimechanism action presented by GM-0111 was ineffective in liquid enema form, likely stemming from poor retention, and subsequent loss of rectal bioavailability. The combination of this broad anti-inflammatory drug and an enema to semisolid formulation resulted in improved outcomes. Behavioral pain responses were decreased in animals receiving SELP-415K GM-0111 formulations, with indications of decreased allodynia. Animal biometrics indicated healthier animals that were producing a higher amount of non-diarrhea fecal content, and capable of maintaining body mass. Histologically, animals receiving SELP-415K GM-0111 formulations had a decreased grade of injury, with increased retention of goblet cells and glands. Goblet cells are responsible for mucus secretion, and retention may improve future outcomes and regeneration of the mucosal barrier. The healthy rectal mucosa shows uniform arrangement of glands, inconspicuous mitotic activity and very little inflammatory cell infiltrate. Rectal mucosa obtained from irradiated animals show variable amounts of epithelial injury and resulting inflammatory infiltrates. This includes increased mitosis (GM-0111 in SELP-415K), crypt drop out (arrow heads), and crypt abscesses (arrows). Additionally, the observed epithelial cells have nuclear pleomorphism (GM-0111 in PBS), loss of goblet cells (PBS), migration of epithelial nuclei towards the lumen (PBS) and flattening of cells on the surface (SELP-415K). There was also some degree of acute neutrophilic inflammation within the mucosa adjacent to the injured epithelium and lymphoplasmacytic cell infiltrate around damaged crypts (GM-0111 in SELP-415K). Preservation or regeneration of crypts seem evident in SELP-415K GM-0111 compositions. Previously, GM-0111 has been shown to protect urothelial cells from LL-37 induced apoptosis[72]. Distinction between preservation and/or regeneration of radiation damage will need to be investigated at earlier timepoints. These improved outcomes illustrate the ability of SELP-415K to retain and improve rectal bioavailability of GM-0111, which can inhibit molecular inflammatory processes from developing.

Sucralfate is another commonly used treatment in the clinic for RIP [32]. Most uses of sucralfate stem from the adhesive properties to inflamed epithelium, protecting the sterile submucosa from inherent luminal flora[73]. Additional antioxidant properties of sucralfate allows for scavenging of free radicals and protection of mucosa from lipid peroxidation[73–75]. Production of epidermal growth factor and prostaglandin E2 are also enhanced with sucralfate. The latter increases mucus secretion by gastrointestinal epithelium goblet cells[76] and may prove problematic for rectal drug delivery. Despite these mechanisms, sucralfate has failed prophylactic clinical trials for RIP, and in some cases increased rectal bleeding and diarrhea[14,32,33]. The key aspect of sucralfate is the formation of a protective barrier; sucralfate treatment following RIP pathophysiology development needs to address pathogen driven inflammation in the submucosa. Both sucralfate and GM-0111 are inherently anti-inflammatory, however in numerous studies GM-0111 has proven to inhibit molecular signaling leading to mucosal inflammatory disorders[37,39,41]. This molecular inhibition of inflammatory events could prevent inflammatory mechanisms from ever occurring.

Typical clinical doses of radiation to the pelvic region range from 45 to 50 Gy in total for neoadjuvant therapies, and up to 85 or 90 Gy for adjuvant treatment prostate and curative gynecological cancers, respectively[4,67]. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapies occur respectively before and after primary treatment courses, typically surgical intervention. However, these doses are typically administered in a fractionated manner to maximize therapeutic efficacy and minimize toxicities in other tissues. Upon presentation of radiotoxicities, cessation of tumor radio-treatment is a common strategy[4]. Therapeutic efficacy, or curvature of cell killing, is described by the Linear Quadratic Mode. In this mode the cell killing curve is described as the α/β ratio. As the α/β ratio decreases, the tumors respond more to larger doses of radiation. Prostate cancers, for example have a low α/β ratio estimated to be ~1.5 Gy. With this low ratio prostate cancers are more responsive to larger doses of radiation than other nearby tissues such as the rectum (α/β = 3–5 G). This could lead to a therapeutic gain that is not proportional to increased toxicities[77]. The radioprotection of SELP-415K GM-0111 in this high dose mouse model illustrates potential in preventing RIP resulting from cases such as severe hypofractionation stereotactic body radiotherapy of prostate cancer patients. By utilizing this preventative approach additional dose escalation may be achievable without proportional increases in toxicities. This is valuable as dose escalation is commonly performed for prostate cancers and is associated with improved outcomes[78]. Further investigation of SELP-415K GM-0111 utility in moderate and extreme hypofractionation approaches is needed. Other tumor types with α/β ratio (>10 Gy) are best treated using smaller fractions to minimize toxicity. Prophylactic intervention for RIP may be of less utility for tumors with a high α/β ratio treated with hyper-fractionated treatment paradigms. Tumors and the rectum are less responsive to increasing fraction size than normal tissues[77]. Our current model which delivered just over 37 Gy likely affects healthy, non-rectal tissue, to a much higher degree than that seen in the clinic. This is difficult to ascertain as rodents have varying sensitivity to ionizing radiation depending on species and strain. The 1×4 cm aperture may have also resulted in irradiation of the small intestine in some animals. These model limitations may obscure results and efficacy, especially in those groups with high behavioral response rates. Additionally, this may challenge efficacy of treatments in later timepoints, as late developing effects may occur. These late developing effects were previously observed in the prior proof of concept study[37]. The chosen radio dose of 37 Gy was similar to a total dose routinely used for prostate cancer patients receiving hypofractionation stereotactic body therapy (36.25, 37.5, 38, etc. Gy)[78]. This dose represents an extremely high, one-time exposure which would not be used in the clinic. However, its purpose to establish severe radiation induced damage is evident as presented by the histology and behavioral pain responses. The observed positive animal outcomes will likely continue in settings with fractionated radiation challenge in tandem with multiple protective SELP-415K GM-0111 administrations.

This investigation evaluated multiple thermoresponsive polymers to form a liquid to semisolid system for rectal delivery of an anti-inflammatory SAGE. Initial indications place emphasis on the importance of gelation rate in bioaccumulation of GM-0111, with more slowly gelling materials capable of providing a higher degree of accumulation. This phenomenon was not directly investigated but could be confirmed or disproven with further controlled experimentation. The efficacy of using GM-0111 SELP-415K delivery systems for prophylactic protection has shown merit during the 7 day follow up study. However, evaluation at earlier and later timepoints should be conducted to establish time dependence of outcomes, as these may vary from late developing tissue responses. For further preclinical advancement, rectal GM-0111 delivery from SELP-415K needs to be assessed for potential systemic absorption and subsequent biodistribution. Further research needs to be conducted to investigate the utility of SAGE for investigating chronic RIP pathophysiology including development of fibrosis and animal survival curves. This includes alteration of total dose, fractionation, and field of irradiation. Future investigations will include radiation fractionating, dose escalation, and posttreatment rather than pretreatment strategies. In future studies translational differences between rodents and humans need to be addressed including pharmacokinetics and toxicology. Rodents have a much narrower rectal passage, tend to defecate involuntarily, more frequently, and have a faster mucus turnover rate than humans[10,79–81]. Despite these limitations, this work has shown that polymer structure for drug delivery in the rectum can have profound results in potential therapeutic outcomes and that SELPs show promise for rectal delivery of radioprotective agents in treatment of RIP.

Conclusion

Thermoresponsive polymer systems are an effective strategy for increasing the rectal accumulation of glycosaminoglycan-based therapeutics. Slower gelation of thermoresponsive polymer solutions likely improves delivery through increased mucus penetration and enhanced surface contact. In situ gelling polymers improved local retention and bioaccumulation with SELP-415K>Poloxamer>SELP-815K. This increased retention and bioaccumulation may allow for less frequent administration and improved patient compliance. GM-0111 delivery with SELP-415K provides protection from RIP animal as seen from decreased behavioral response rates, retention of animal mass, and improved histological outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Figure 9: Histological analysis of rectal tissues.

A) Representative tissue images stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E). Healthy tissue did not exhibit any abnormalities. All other irradiated tissues showed crypt abscesses (arrows) or dropping of crypts altogether (arrowheads). (Scalebar = 50 μm) B) Blinded scoring of injury grade for each tissue (***: p < 0.001).

Acknowledgements

Financial support for this study was made possible by the National Institutes of Health (1RO1CA227225).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Hamid Ghandehari is founder and shareholder in TheraTarget, LCC. This study does not constitute a conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Lee JK, Agrawal D, Thosani N, Al-Haddad M, Buxbaum JL, Calderwood AH, Fishman DS, Fujii-Lau LL, Jamil LH, Jue TL, Khashab MA, Law JK, Naveed M, Qumseya BJ, Sawhney MS, Storm AC, Yang J, Wani SB, ASGE guideline on the role of endoscopy for bleeding from chronic radiation proctopathy, Gastrointest. Endosc. 90 (2019) 171–182.e1. 10.1016/j.gie.2019.04.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Trzcinski R, Mik M, Dziki L, Dziki A, Radiation Proctitis, in: Proctol. Dis. Surg. Pract, InTech, 2018: pp. 116–124. 10.5772/intechopen.76200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mazulis A, Ehrenpreis ED, Radiation proctopathy, Radiat. Ther. Pelvic Malig. Its Consequences. (2015) 131–141. 10.1007/978-1-4939-2217-8_9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Do NL, Nagle D, Poylin VY, Radiation Proctitis: Current Strategies in Management, Gastroenterol. Res. Pract 2011 (2011) 1–9. 10.1155/2011/917941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Vanneste BGL, Van De Voorde L, de Ridder RJ, Van Limbergen EJ, Lambin P, van Lin EN, Chronic radiation proctitis: tricks to prevent and treat, Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 30 (2015) 1293–1303. 10.1007/s00384-015-2289-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bansal N, Soni A, Kaur P, Chauhan AK, Kaushal V, Exploring the management of radiation proctitis in current clinical practice, J. Clin. Diagnostic Res 10 (2016) XE01–XE06. 10.7860/JCDR/2016/17524.7906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Anseline PF, Lavery IC, Fazio VW, Jagelman DG, Weakley FL, Radiation injury of the rectum. Evaluation of surgical treatment, Ann. Surg. 194 (1981) 716–724. 10.1097/00000658-198112000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Pricolo VE, Shellito PC, Surgery for radiation injury to the large intesine, Dis. Colon Rectum. 37 (1994) 675–684. 10.1007/BF02054411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ayerdi J, Moinuddeen K, Loving A, Wiseman J, Deshmukh N, Diverting Loop Colostomy for the Treatment of Refractory Gastrointestinal Bleeding Secondary to Radiation Proctitis, Mil. Med 166 (2001) 1091–1093. 10.1093/milmed/166.12.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lenz L, Rohr R, Nakao F, Libera E, Ferrari A, Chronic radiation proctopathy: A practical review of endoscopic treatment, World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 8 (2016) 151. 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i2.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zinicola R, Rutter M, Falasco G, Brooker J, Cennamo V, Contini S, Saunders B, Haemorrhagic radiation proctitis: endoscopic severity may be useful to guide therapy, Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 18 (2003) 439–444. 10.1007/s00384-003-0487-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rustagi T, Endoscopic management of chronic radiation proctitis, World J. Gastroenterol. 17 (2011) 4554. 10.3748/wjg.v17.i41.4554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].McElvanna K, Wilson A, Irwin T, Sucralfate paste enema: a new method of topical treatment for haemorrhagic radiation proctitis, Color. Dis. 16 (2014) 281–284. 10.1111/codi.12507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].O’Brien PC, Franklin CI, Dear KBG, Hamilton CC, Poulsen M, Joseph DJ, Spry N, Denham JW, A phase III double-blind randomised study of rectal sucralfate suspension in the prevention of acute radiation proctitis, Radiother. Oncol. 45 (1997) 117–123. 10.1016/S0167-8140(97)00146-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sanguineti G, Franzone P, Marcenaro M, Vitale V, Sucralfate Versus Mesalazine Versus Hydrocortisone in the Prevention of Acute Proctitis During Conformal Radiotherapy for Prostate Carcinoma: A Randomized Study, Proc. 44th Annu. ASTRO Meet. 54 (2002) 110–111. 10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Goldstein F, Khoury J, Thornton J, Treatment of chronic radiation enteritis and colitis with salicylazosulfapyridine and systemic corticosteroids. A pilot study., Am. J. Gastroenterol. 65 (1976) 201–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Jahraus CD, Bettenhausen D, Malik U, Sellitti M, St WH. Clair, Prevention of acute radiation-induced proctosigmoiditis by balsalazide: A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial in prostate cancer patients, Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 63 (2005) 1483–1487. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kennedy M, Bruninga K, Mutlu EA, Losurdo J, Choudhary S, Keshavarzian A, Successful and sustained treatment of chronic radiation proctitis with antioxidant vitamins E and C, Am. J. Gastroenterol. 96 (2001) 1080–1084. 10.1016/S0002-9270(01)02305-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Raman RR, Two percent formalin retention enemas for hemorrhagic radiation proctitis: A preliminary report, Dis. Colon Rectum. 50 (2007) 1032–1039. 10.1007/s10350-007-0241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Alfadhli AA, Alazmi WM, Ponich T, Howard JM, Prokopiw I, Alaqeel A, Gregor JC, Efficacy of argon plasma coagulation compared with topical formalin application for chronic radiation proctopathy, Can. J. Gastroenterol. 22 (2008) 129–132. 10.1155/2008/964912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ouwendijk R, Tetteroo GWM, Bode W, De Graaf EJR, Local formalin instillation: An effective treatment for uncontrolled radiation-induced hemorrhagic proctitis, Dig. Surg. 19 (2002) 52–55. 10.1159/000052006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Vernia P, Fracasso PL, Casale V, Villotti G, Marcheggiano A, Stigliano V, Pinnaro P, Bagnardi V, Caprilli R, Topical butyrate for acute radiation proctitis: Randomised, crossover trial, Lancet. 356 (2000) 1232–1235. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02787-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Venkitaraman R, Coffey J, Norman AR, James FV, Huddart RA, Horwich A, Dearnaley DP, Pentoxifylline to Treat Radiation Proctitis: A Small and Inconclusive Randomised Trial, Clin. Oncol. 20 (2008) 288–292. 10.1016/j.clon.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kim TO, Song GA, Lee SM, Kim GH, Heo J, Kang DH, Cho M, Rebampide enema therapy as a treatment for patients with chronic radiation proctitis: Initial treatment or when other methods of conservative management have failed, Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 23 (2008) 629–633. 10.1007/s00384-008-0453-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ehrenpreis ED, Jani A, Levitsky J, Ahn J, Hong J, A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of retinol palmitate (Vitamin A) for symptomatic chronic radiation proctopathy, Dis. Colon Rectum. 48 (2005) 1–8. 10.1007/s10350-004-0821-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Rombeau JL, Short Chain Fatty Acids are Effective in Short-Term Treatment of Chronic Radiation Proctitis:Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Trial, Dis. Colon Rectum. 42 (1999) 795–796. 10.1007/BF02236938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Niv Y, Henkin Y, Estrogen-progestin therapy and coronary heart disease in radiation- induced rectal telangiectases., J. Clin. Gastroenterol 21 (1995) 295–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Grigsby PW, Pilepich V. M, Parsons CL, Preliminary Results of a Phase I/II Study of Sodium Pentosanpolysulfate in the Treatment of Chronic Radiation-Induced Proctitis, Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 13 (1990) 28–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Khan AM, Birk JW, Anderson JC, Georgsson M, Park TL, Smith CJ, Comer GM, A prospective randomized placebo-controlled double-blinded pilot study of misoprostol rectal suppositories in the prevention of acute and chronic radiation proctitis symptoms in prostate cancer patients, Am. J. Gastroenterol. 95 (2000) 1961–1966. 10.1016/S0002-9270(00)01052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hong JJ, Park W, Ehrenpreis ED, Review article: current therapeutic options for radiation proctopathy, Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 15 (2001) 1253–1262. 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Shadad AK, Sullivan FJ, Martin JD, Egan LJ, Gastrointestinal radiation injury: Prevention and treatment, World J. Gastroenterol. 19 (2013) 199–208. 10.3748/wjg.v19.i2.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hovdenak N, Sørbye H, Dahl O, Sucralfate does not ameliorate acute radiation proctitis: Randomised study and meta-analysis, Clin. Oncol 17 (2005) 485–491. 10.1016/j.clon.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kneebone A, Mameghan H, Bolin T, Berry M, Turner S, Kearsley J, Graham P, Fisher R, Delaney G, The effect of oral sucralfate on the acute proctitis associated with prostate radiotherapy: a double-blind, randomized trial, Int. J. Radiat. Oncol 51 (2001) 628–635. 10.1016/S0360-3016(01)01660-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kertesz T, Herrmann MKA, Zapf A, Christiansen H, Hermann RM, Pradier O, Schmidberger H, Hess CF, Hille A, Effect of a Prostaglandin - Given Rectally for Prevention of Radiation-Induced Acute Proctitis - On Late Rectal Toxicity : RRRRResults of a Phase III Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Study, Strahlentherapie Und Onkol. 185 (2009) 596–602. 10.1007/s00066-009-1978-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kneebone A, Mameghan H, Bolin T, Berry M, Turner S, Kearsley J, Graham P, Fisher R, Delaney G, Effect of oral sucralfate on late rectal injury associated with radiotherapy for prostate cancer: A double-blind, randomized trial, Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 60 (2004) 1088–1097. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].O’Brien PC, Franklin CI, Poulsen MG, Joseph DJ, Spry NS, Denham JW, Acute symptoms, not rectally administered sucralfate, predict for late radiation proctitis: Longer term follow-up of a phase III trial - Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group, Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 54 (2002) 442–449. 10.1016/S0360-3016(02)02931-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Jensen MM, Jia W, Isaacson KJ, Schults A, Cappello J, Prestwich GD, Oottamasathien S, Ghandehari H, Silk-elastinlike protein polymers enhance the efficacy of a therapeutic glycosaminoglycan for prophylactic treatment of radiation-induced proctitis, J. Controlled Release. 263 (2017) 46–56. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Savage JR, Pulsipher A, Rao NV, Kennedy TP, Prestwich GD, Ryan ME, Lee WY, A Modified Glycosaminoglycan, GM-0111, Inhibits Molecular Signaling Involved in Periodontitis, PLoS One. 11 (2016) e0157310. 10.1371/journal.pone.0157310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Jensen MM, Jia W, Schults AJ, Isaacson KJ, Steinhauff D, Green B, Zachary B, Cappello J, Ghandehari H, Oottamasathien S, Temperature-responsive silk-elastinlike protein polymer enhancement of intravesical drug delivery of a therapeutic glycosaminoglycan for treatment of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome, Biomaterials. 217 (2019) 119293. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Pulsipher A, Qin X, Thomas AJ, Prestwich GD, Oottamasathien S, Alt JA, Prevention of sinonasal inflammation by a synthetic glycosaminoglycan, Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 7 (2017) 177–184. 10.1002/alr.21865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Zhang J, Xu X, Rao NV, Argyle B, McCoard L, Rusho WJ, Kennedy TP, Prestwich GD, Krueger G, Novel Sulfated Polysaccharides Disrupt Cathelicidins, Inhibit RAGE and Reduce Cutaneous Inflammation in a Mouse Model of Rosacea, PLoS One. 6 (2011) e16658. 10.1371/journal.pone.0016658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Cappello J, Crissman J, Dorman M, Mikolajczak M, Textor G, Marquet M, Ferrari F, Genetic engineering of structural protein polymers, Biotechnol. Prog. 6 (1990) 198–202. 10.1021/bp00003a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Gustafson JA, Ghandehari H, Silk-elastinlike protein polymers for matrix-mediated cancer gene therapy, Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 62 (2010) 1509–1523. 10.1016/j.addr.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Haider M, Leung V, Ferrari F, Crissman J, Powell J, Cappello J, Ghandehari H, Molecular Engineering of Silk-Elastinlike Polymers for Matrix-Mediated Gene Delivery: Biosynthesis and Characterization, Mol. Pharm. 2 (2005) 139–150. 10.1021/mp049906s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Dandu R, Von Cresce A, Briber R, Dowell P, Cappello J, Ghandehari H, Silk–elastinlike protein polymer hydrogels: Influence of monomer sequence on physicochemical properties, Polymer (Guildf). 50 (2009) 366–374. 10.1016/j.polymer.2008.11.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Barichello J, Enhanced rectal absorption of insulin-loaded Pluronic® F-127 gels containing unsaturated fatty acids, Int. J. Pharm. 183 (1999) 125–132. 10.1016/S0378-5173(99)00090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Charrueau C, Tuleu C, Astre V, Grossiord J-L, Chaumeil J-C, Poloxamer 407 as a Thermogelling and Adhesive Polymer for Rectal Administration of Short-Chain Fatty Acids, Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 27 (2001) 351–357. 10.1081/DDC-100103735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ryu J-M, Chung S-J, Lee M-H, Kim C-K, Chang-Koo Shim, Increased bioavailability of propranolol in rats by retaining thermally gelling liquid suppositories in the rectum, J. Controlled Release. 59 (1999) 163–172. 10.1016/S0168-3659(98)00189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Barakat NS, In vitro and in vivo characteristics of a thermogelling rectal delivery system of etodolac, AAPS PharmSciTech. 10 (2009) 724–731. 10.1208/s12249-009-9261-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Poursaid A, Jensen MM, Nourbakhsh I, Weisenberger M, Hellgeth JW, Sampath S, Cappello J, Ghandehari H, Silk-Elastinlike Protein Polymer Liquid Chemoembolic for Localized Release of Doxorubicin and Sorafenib, Mol. Pharm. 13 (2016) 2736–2748. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Price R, Poursaid A, Cappello J, Ghandehari H, Effect of shear on physicochemical properties of matrix metalloproteinase responsive silk-elastinlike hydrogels, J. Controlled Release. 195 (2014) 92–98. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.07.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Gustafson JA, Price RA, Frandsen J, Henak CR, Cappello J, Ghandehari H, Synthesis and characterization of a matrix-metalloproteinase responsive silk-elastinlike protein polymer, Biomacromolecules. 14 (2013) 618–625. 10.1021/bm3013692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Rudick CN, Schaeffer AJ, Klumpp DJ, Pharmacologic attenuation of pelvic pain in a murine model of interstitial cystitis, BMC Urol 9 (2009) 16. 10.1186/1471-2490-9-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Hovdenak N, Fajardo LF, Hauer-Jensen M, Acute radiation proctitis: A sequential clinicopathologic study during pelvic radiotherapy, Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 48 (2000) 1111–1117. 10.1016/S0360-3016(00)00744-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Jullien N, Blirando K, Milliat F, Sabourin J-C, Benderitter M, François A, Up-Regulation of Endothelin Type A Receptor in Human and Rat Radiation Proctitis: Preclinical Therapeutic Approach With Endothelin Receptor Blockade, Int. J. Radiat. Oncol 74 (2009) 528–538. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.12.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Nunes R, Sarmento B, Neves J. Das, Formulation and delivery of anti-HIV rectal microbicides: Advances and challenges, J. Controlled Release. 194 (2014) 278–294. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].van Hoogdalem EJ, de Boer AG, Breimer DD, Pharmacokinetics of Rectal Drug Administration, Part I, Clin. Pharmacokinet 21 (1991) 11–26. 10.2165/00003088-199121010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Hua S, Physiological and Pharmaceutical Considerations for Rectal Drug Formulations, Front. Pharmacol. 10 (2019) 1–16. 10.3389/fphar.2019.01196.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Dumortier G, Grossiord JL, Agnely F, Chaumeil JC, A Review of Poloxamer 407 Pharmaceutical and Pharmacological Characteristics, Pharm. Res. 23 (2006) 2709–2728. 10.1007/s11095-006-9104-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Parker Wu, McKay Xu, Kaplan, Design of Silk-Elastin-Like Protein Nanoparticle Systems with Mucoadhesive Properties, s. Biomater. 10 (2019) 49. 10.3390/jfb10040049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Lin H-R, Tseng C-C, Lin Y-J, Ling M-H, A Novel In-Situ-Gelling Liquid Suppository for Site-Targeting Delivery of Anti-Colorectal Cancer Drugs, J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 23 (2012) 807–822. 10.1163/092050611X560861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Ban E, Kim C-K, Design and evaluation of ondansetron liquid suppository for the treatment of emesis, Arch. Pharm. Res. 36 (2013) 586–592. 10.1007/s12272-013-0049-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Özgüney I, Kardhiqi A, Yıldız G, Ertan G, In vitro–in vivo evaluation of in situ gelling and thermosensitive ketoprofen liquid suppositories, Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 39 (2014) 283–291. 10.1007/s13318-013-0157-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Sinha SR, Nguyen LP, Inayathullah M, Malkovskiy A, Habte F, Rajadas J, Habtezion A, A Thermo-Sensitive Delivery Platform for Topical Administration of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Therapies, Gastroenterology. 149 (2015) 52–55.e2. 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].MacDermott RP, Donaldson RM, Trier JS, Glycoprotein Synthesis and Secretion by Mucosal Biopsies of Rabbit Colon and Human Rectum, J. Clin. Invest. 54 (1974) 545–554. 10.1172/JCI107791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Hayashi M, Tomita M, Awazu S, Transcellular and paracellular contribution to transport processes in the colorectal route, Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 28 (1997) 191–204. 10.1016/S0169-409X(97)00072-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Porouhan P, Farshchian N, Dayani M, Management of radiation-induced proctitis, J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care. 8 (2019) 2173. 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_333_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Wu XR, Liu XL, Katz S, Shen B, Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of ulcerative proctitis, chronic radiation proctopathy, and diversion proctitis, Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 21 (2015) 703–715. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Oliveira-Nascimento L, Massari P, Wetzler LM, The Role of TLR2 in Infection and Immunity, Front. Immunol 3 (2012) 1–17. 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Vaure C, Liu Y, A Comparative Review of Toll-Like Receptor 4 Expression and Functionality in Different Animal Species, Front. Immunol. 5 (2014) 1–15. 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Tao L, Tian S, Zhang J, Liu Z, Robinson-McCarthy L, Miyashita S-I, Breault DT, Gerhard R, Oottamasathien S, Whelan SPJ, Dong M, Sulfated glycosaminoglycans and low-density lipoprotein receptor contribute to Clostridium difficile toxin A entry into cells, Nat. Microbiol 4 (2019) 1760–1769. 10.1038/s41564-019-0464-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Lee WY, Savage JR, Zhang J, Jia W, Oottamasathien S, Prestwich GD, Prevention of anti-microbial peptide LL-37-induced apoptosis and ATP release in the urinary bladder by a modified glycosaminoglycan., PLoS One. 8 (2013) 1–13. 10.1371/journal.pone.0077854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Martinez CAR, Rodrigues MR, Sato DT, da Silva CMG, Kanno DT, Mendonça RLDS, Pereira JA, Evaluation of the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of the sucralfate in diversion colitis, J. Coloproctology. 35 (2015) 90–99. 10.1016/j.jcol.2015.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Wada K, Kamisaki O, Kitano M, Kishimot Y, Nakamoto K, Itoh T, Effects of Sucralfate on Acute Gastric Mucosal Injury and Gastric Ulcer Induced by Ischemia-Reperf usion in Rats, Pharmacology. 54 (1997) 57–63. 10.1159/000139470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Kochhar R, Mehta SK, Aggarwal R, Dhar A, Patel F, Sucralfate enema in ulcerative rectosigmoid lesions, Dis. Colon Rectum. 33 (1990) 49–51. 10.1007/BF02053202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Pereira JA, Rodrigues MR, Sato DT, Júnior PPS, Dias AM, da Silva CG, Martinez CAR, Evaluation of sucralfate enema in experimental diversion colitis, J. Coloproctology 33 (2013) 182–190. 10.1016/j.jcol.2013.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Hegemann N-S, Guckenberger M, Belka C, Ganswindt U, Manapov F, Li M, Hypofractionated radiotherapy for prostate cancer., Radiat. Oncol. 9 (2014) 275. 10.1186/s13014-014-0275-6.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].De Bari B, Arcangeli S, Ciardo D, Mazzola R, Alongi F, Russi EG, Santoni R, Magrini SM, Jereczek-Fossa BA, Extreme hypofractionation for early prostate cancer: Biology meets technology, Cancer Treat. Rev 50 (2016) 48–60. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Padmanabhan P, Grosse J, Asad ABMA, Radda GK, Golay X, Gastrointestinal transit measurements in mice with 99mTc-DTPA-labeled activated charcoal using NanoSPECT-CT, EJNMMI Res. 3 (2013) 60. 10.1186/2191-219X-3-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Melo M, Nunes RB, das Neves J, Colorectal distribution and retention of polymeric nanoparticles following incorporation into a thermosensitive enema, Biomater. Sci. 7 (2019) 3801–3811. 10.1039/C9BM00759H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Mulè F, Amato A, Serio R, Gastric emptying, small intestinal transit and fecal output in dystrophic (mdx) mice, J. Physiol. Sci. 60 (2010) 75–79. 10.1007/s12576-009-0060-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.