ABSTRACT

Introduction

The uptake of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in France remains low. The aim of this study was to identify factors associated with the uptake of the HPV vaccine in girls aged 11–14 years in France.

Methods

We conducted a telephone survey among a quota sample of 1102 mothers of 11-14-year-old daughters residing in mainland France, using the French Survey Questionnaire for the Determinants of HPV Vaccine Hesitancy (FSQD-HPVH). The dependent variable was the uptake of at least one dose of the HPV vaccine in the daughter. The independent variables included the FSQD-HPVH item variables, the Global Vaccine Confidence Index item variables, the daughter’s age, and the mother’s socioeconomic status.

Results

Overall, 38.6% of the mothers indicated that their daughter received at least one dose of the HPV vaccine. The multivariate analysis revealed that agreeing with the statement that doctors/health care providers believe vaccinating girls against HPV was a good idea, and having asked questions to the attending doctor about HPV vaccines were associated with a higher HPV vaccine uptake (OR = 4.99 , 95% CI [2.09–11.89]; and OR = 3.44, 95% CI [2.40–4.92]). Mother’s belief that her daughter was too young to be vaccinated against HPV (OR = 0.16 , 95% CI [0. 09–0.29]) and lower daughter’s age (OR = 0.17 , 95% CI [0.10–0.28] for girls aged 11 compared to those aged 14) were found strongly inversely associated with HPV vaccination, followed by agreeing with the statement that the HPV vaccine was unsafe (OR = 0.42 , 95% CI [0.26–0.67]), identifying as true the statement that HPV was very rare (OR = 0.49 , 95% CI [0.31–0.77]), and the mother’s refusal of own vaccination (OR = 0.57 , 95% CI [0.40–0.80]).

Conclusion

We have identified important determinants associated with HPV vaccine uptake in France. Interventions designed to improve HPV vaccine uptake should be tailored to address these determinants.

KEYWORDS: HPV vaccine, vaccine hesitancy, determinants, mothers, daughters

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer among women worldwide. With an estimated 2 835 new cases of cervical cancer diagnosed and 1 084 related deaths in France,1 it is also the fourth most common female cancer in women aged 15 to 44 years in France.2

Cervical cancer remains a deadly disease, but it is preventable through screening and vaccination against the papillomavirus (HPV) infection, its etiologic agent. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Health Assembly have called for its elimination by 2030.3

In France, vaccination against HPV has been recommended since 2007 for girls and 2019 for boys. In 2022, it is recommended for adolescent girls and boys aged 11 to 14 years (with catch-up vaccination until 19 years old),4 with the recommendation for boys implemented since January.5 Although France was one of the first three countries to introduce HPV vaccination for girls, the uptake of HPV vaccine in French girls remains low. Coverage of the full course of HPV vaccine coverage in France in 2020 was around 33% in girls aged 16 years,6 well below the 2014–2019 French national cancer control plan goal of 60%,7,8 In 2017, the French National Authority of Health (Haute Autorité de Santé, HAS) recognized primary cervical cancer prevention through vaccination and screening as a public health priority.9 In 2019, the French Prime Minister issued a decree relating to the implementation of two regional experiments aiming at improving HPV vaccination coverage. The selected regions were French Guiana and the Grand-Est region. The interventions included health care professionals training and school based vaccination-campaigns.10

HPV vaccination in France remains opportunistic, since there is no national school-vaccination program, or otherwise organized. Thus, parents must make an appointment with their doctor to obtain vaccine prescription, obtain the vaccine from a pharmacy, and then make another appointment for its administration. The national social security system covers 65% of the cost of the vaccine (115.20 € per dose) and the remaining 35% has to be paid by the individual (or covered through complementary insurance cover).

Multiple barriers to HPV vaccination have been reported in the literature, including disadvantaged background, lack of health coverage, residence in a less urbanized area,11,12 and mother’s ethnicity.13 The literature has also reported levels of knowledge about cervical cancer/HPV, maternal history of abnormal cytology, and opinions about vaccination, in general, as determinants of HPV vaccination.14 In France, several studies have examined the role of common epidemiologic factors such as socioeconomic status and healthcare supply,15,16 or cervical cancer screening attitudes in the mothers17 as determinants of HPV vaccination coverage. However, no study has investigated this issue through the prism of factors related to vaccine hesitancy, defined by the WHO Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE) working group as “the delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccination services.” This approach classifies the determinants of vaccine hesitancy into three main domains: (i) contextual influences (e.g., communication and social media); (ii) individual and group influences (e.g., lack of perceived benefit of the vaccine); and (iii) vaccine/vaccination-specific issues (e.g., the strength of the recommendation of healthcare professionals).18 This approach was used in a recently published systematic literature review of factors affecting vaccination coverage in Latin America.19 Being mindful that “vaccine hesitancy is complex and context-specific, varying across geographies and vaccine types”,20 we have developed the French Survey Questionnaire for the Determinants of HPV Vaccine Hesitancy (FSQD-HPVH) to be used in the French context.2 The purpose of the present study was to pilot-test this questionnaire in a representative group of French mothers and use it to identify factors associated with the uptake of HPV vaccine in girls aged 11–14 years in France.

Material and methods

Study design and population

We conducted a cross-sectional telephone survey among a sample of mothers of 11-14-year-old daughters residing in mainland France. The study population was enrolled using quota sampling, a non-probability sampling method, to ensure a nationally representative sample of mothers of girls aged 11 to 14 years. Because the proportion of households with teenage girls of this age is very low, random sampling would have been challenging to implement in this setting. The quota sample was representative according to the following characteristics: region of residence, socio-professional category (SPC) of the reference person in the household, and the number of children in the household by comparison with the latest national census.21 IPSOS, a global market, and social research company, conducted the sampling and the field interviews using computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) systems. The interviewers underwent training and were required to follow standard recruitment and data collection procedures. After a week of pilot-testing among a sample of 30 mothers using the same eligibility and quota criteria as for the primary survey, the data-collection period started in April 2021 and lasted three weeks.

After obtaining oral informed consent on a study on HPV vaccination conducted on behalf of the French national institute of health and medical research (Inserm, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale), the interviewer introduced the survey with the following explanatory paragraph: “Vaccination against Human Papillomaviruses (HPV) prevents infection by these widespread and sexually transmitted viruses, responsible for cervical cancer. Despite more than ten years of experience with efficacy and safety, HPV vaccination coverage remains exceptionally low in France (<30%) compared to other European countries. Like many mothers of teenage girls, you will have to make a decision about your daughter’s HPV vaccination. By interviewing mothers, researchers will be able to understand better their attitudes toward this vaccination, which will then allow health professionals to better assist them in deciding to vaccinate their daughters”. Agreements were made with the interviewer on participant recruitment appointment if the mother was not immediately available. Participants received no incentive whatsoever for completing the survey.

Study variables

The dependent variable was the uptake of at least one dose of the HPV vaccine in the 11-14-year-old daughter (the oldest in the case of two daughters of the same age range). This binary variable was derived from the response to the single answer question about the Precaution Adoption Process Model (PAPM) stage for HPV vaccination:22,23 “Which of the following best describes your thoughts about the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine for your daughter”: unaware that the HPV vaccine could be given to their daughter (stage 1)/aware that the HPV vaccine could be given to their daughter, but never thought about vaccinating their daughter against HPV (stage 2)/undecided about vaccinating their daughter against HPV (stage 3)/have decided they DO NOT want to vaccinate their daughter against HPV (stage 4)/decided they DO want to vaccinate their daughter against HPV (stage 5)/daughter has already received the HPV vaccine (stage 6). This later stage is our dependent variable.

The independent variables included the FSQD-HPVH item variables,2 the Global Vaccine Confidence Index (GVCI) item variables,24 daughter’s age, the three quotas variables (region of residence, SPC of the reference person in the household, and the number of children in the household), and mother’s socioeconomic status: age, level of education, nationality, whether they had at least one immigrated parent, health insurance status (private supplementary insurance, public insurance for the underprivileged).

Mother’s awareness about the HPV vaccine before the survey was assessed by the answer to the question “Have you heard about the HPV vaccine before taking this survey?”

Sample size calculation

A sample size of 1100 mothers was deemed necessary to detect as statistically significant an odds ratio of uptake of at least one dose of HPV vaccine of 1.8. This sample size provided 80% power to perform a multivariate analysis with 33 independent variables to assess the determinants of HPV vaccine uptake according to the rule of thumb of 10 events per independent variable.25 The sample size calculation assumptions were: alpha risk of 5%; the prevalence of exposure to factors influencing HPV vaccine uptake of 10%; and uptake rate of at least one dose of HPV vaccine in the non-exposed mothers of 30%.

Statistical analysis

The data set provided by IPSOS included data weighted according to the French general population census of the French National Institute for Statistics and Economic Studies. We used descriptive statistics to summarize the responses to each question. We reported continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and categorical variables as absolute count and relative frequency (%). Weighted data were reported for sociodemographic descriptive statistics, along with raw data, to indicate the quality of sampling. Since we observed no difference between weighted and raw data (Table 1), the rest of the analyses were performed using raw data. We used the χ2 test to compare the FSQD-HPVH variables between the mothers who reported that their daughters received at least one dose of the HPV vaccine and the group of mothers who reported that their daughters did not receive any dose of the HPV vaccine. To identify the variables that were independently associated with HPV vaccination uptake, we conducted multivariate logistic regression models using weights to account for the quota sampling method. The multivariate model was built using a backward process, with a significance level of 0.05 for a variable to stay in the model. Initial candidate variables were the variables from the FSQD-HPVH (except the responses to the conditional questions that were not asked to the whole sample; for example, the type of internet website for mothers responding Internet to the question related to the source of information), the four items of the GVCI, as well as the sociodemographic variables with P < 0·20 in the χ2 test for differences group. We checked multicollinearity before including variables in the multivariate logistic model. We reported adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with their respective 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 1102 mothers included in the study.

| Unweighted data |

Weighted data |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n or mean | (% or SD) | n or mean | (% or SD) | ||

| Age (years) | 43.4 | (3.6) | 43.3 | (3.6) | |

| Lives with a partner | |||||

| Yes | 818 | (74.2) | 814 | (73.9) | |

| No | 284 | (25.8) | 288 | (26.1) | |

| Level of education (2 missing values) | |||||

| < High school diploma | 137 | (12.4) | 142 | (13.0) | |

| High school diploma- Two year post high school diploma | 513 | (46.6) | 521 | (47.4) | |

| > Two year post high school diploma | 449 | (40.7) | 435 | (39.6) | |

| Nationality (1 missing value) | |||||

| French by birth | 1024 | (92.9) | 1023 | (92.8) | |

| French by acquisition | 53 | (4.8) | 53 | (4.8) | |

| Foreign | 24 | (2.2) | 25 | (2.2) | |

| Immigrated parent (1 missing value) | |||||

| Yes | 157 | (14.2) | 158 | (14.3) | |

| No | 944 | (85.7) | 943 | (85.6) | |

| Supplemental health insurance (1 missing value) |

|||||

| Yes | 1049 | (95.2) | 1046 | (94.9) | |

| No | 52 | (4.7) | 55 | (5.0) | |

| Subsidized Supplementary Health Insurance (1 missing value) | |||||

| Yes | 66 | (6.0) | 70 | (6.3) | |

| No | 1035 | (93.9) | 1031 | (93.6) | |

| Recipient of minimal social benefit | |||||

| Yes | 47 | (4.3) | 50 | (4.6) | |

| No | 1055 | (95.7) | 1052 | (95.4) | |

Inferential statistical measures (95% CI and P-values), commonly used to make inferences about the larger population from which the sample is drawn, are meant only for indicative purposes in the present study, as it is difficult to guarantee that the study sample was representative for characteristics other than those for which quotas units have been determined.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina). All statistical tests involved were two-sided, and a P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Pilot phase

Changes were made to the wording of one question: “I am favorable to the 11 vaccines mandatory for children born since 1 January 2018,” reformulated to “I am favorable to the mandatory vaccination for children under two years of age.” One item was removed because it was redundant. No problem of questions understanding was detected.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants

As shown in Table 2, adequate numbers were achieved for all quotas.

Table 2.

Representativeness of demographic quotas.

| Quota category | Quota | Percentage of respondents in each quota (%) | Percentage representative of the French general population (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic region of residence | Parisian Region | 19.0 | 19.2 |

| North West | 23.4 | 23.5 | |

| North East | 22.4 | 22.6 | |

| South West | 10.7 | 10.4 | |

| South East | 24.5 | 24.3 | |

| Socio-professional category (SPC) of the reference person in the household | Upper | 51.5 | 48.4 |

| Medium and low | 45.5 | 47.7 | |

| Unemployed | 3.1 | 3.9 | |

| Number of children in the household | One | 15.7 | 16.1 |

| More than one | 84.3 | 83.9 |

The mean age of the survey respondents was 43.3 years (SD, 3.6). The majority of mothers had attained an educational level between high school diploma and two-year post-high school diploma (47%), lived with a partner (74%), had private health insurance (95%), and were of French nationality by birth (93%); and 84% had more than one child (Table 2). Ninety seven percent of the mothers reported having heard about the HPV vaccine before taking the survey (Table 1).

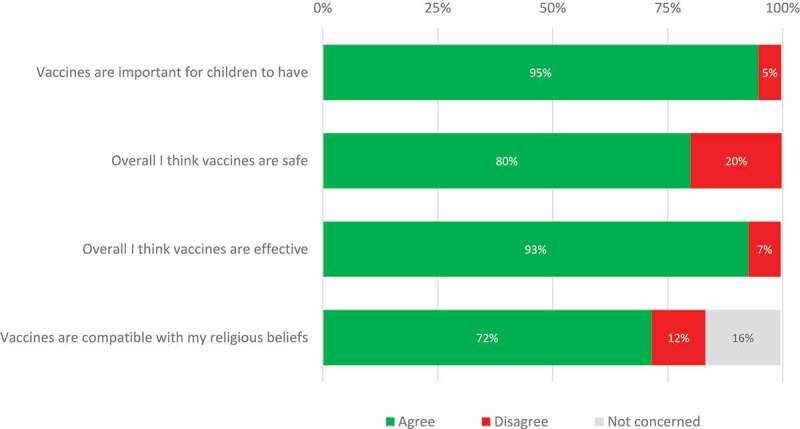

Global vaccine confidence index

The majority of respondents agreed with the statement that “Vaccines are important for children to have” (94.6%), “Overall, I think vaccines are safe” (79.9%), “Overall I think vaccines are effective” (92.6%), “Vaccines are compatible with my religious beliefs” (71.5%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Global vaccine confidence index items.

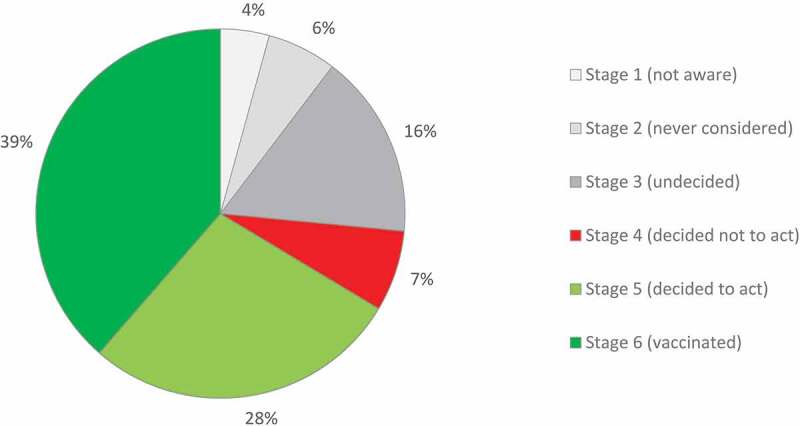

Precaution Adoption Process Model stage and HPV vaccination rate

A minority of mothers were in PAPM stages 1 (4.3%) and 2 (6.1%) (unaware that the HPV vaccine could be given to their daughter, and aware that the HPV vaccine could be given to their daughter but never thought about vaccinating them, respectively). While 16.1% were undecided (stage 3), 7.1% decided not to (stage 4) and 27.8% decided to (stage 5) vaccinate their daughter. Thus, HPV vaccination uptake (reported daughter’s receipt of at least one dose of HPV vaccine) was 38.6% (PAPM stage 6) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Precaution Adoption Process Model stage for HPV vaccination.

Descriptive and group comparison analyses of FSQD-HPVH variables

The responses to the FSQD-HPVH are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Distribution of FSQD-HPVH survey variables by HPV vaccination status (unweighted data). Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding.

| Total (n=1102) |

Vaccinated daughters (n=425) |

Unvaccinated daughters (n=677) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | P value | |||

| CONTEXTUAL INFLUENCES | |||||||||

| COMMUNICATION AND MEDIA ENVIRONMENT | How did you hear about the HPV vaccine?a, b | ||||||||

| Recommendation of the attending physician | 491 | (44.6) | 251 | (59.1) | 240 | (35.5) | <0.0001 | ||

| Recommendation of a pediatrician | 95 | (8.6) | 41 | (9. 6) | 54 | (8.0) | 0.4705 | ||

| Recommendation of a gynecologist | 232 | (21.1) | 110 | (25.9) | 122 | (18.0) | 0.0066 | ||

| Television | 266 | (24.1) | 88 | (20.7) | 178 | (26.3) | 0.0109 | ||

| Social media | 55 | (5.0) | 15 | (3.5) | 40 | (5.9) | 0.0531 | ||

| Written press | 150 | (13.6) | 53 | (12.5) | 97 | (14.3) | 0.2384 | ||

| Family | 196 | (17.8) | 74 | (17.4) | 122 | (18.0) | 0.5379 | ||

| Friends | 202 | (18.3) | 76 | (17.9) | 126 | (18.6) | 0.5029 | ||

| School | 39 | (3.5) | 16 | (3.8) | 23 | (3.4) | 0.8632 | ||

| Other | 175 | (15.9) | 58 | (13.6) | 117 | (17.3) | 0.0525 | ||

| HISTORICAL INFLUENCES | Since the controversy over vaccination against H1N1 flu, I have less confidence in French vaccination recommendations | <0.0001 | |||||||

| Agree | 348 | (31.6) | 88 | (20.7) | 260 | (38.4) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 16 | (1. 5) | 3 | (0.7) | 13 | (1.9) | |||

| Disagree | 724 | (65.7) | 329 | (77.4) | 395 | (58.3) | |||

| Don’t know | 8 | (0.7) | 3 | (0.7) | 5 | (0.7) | |||

| Unanswered question | 6 | (0.5) | 2 | (0.5) | 4 | (0.6) | |||

| Since the controversy over the hepatitis B vaccine, I have less confidence in the healthcare system | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Agree | 350 | (31.8) | 85 | (20.0) | 265 | (39. 1) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 13 | (1.2) | 3 | (0.7) | 10 | (1.5) | |||

| Disagree | 726 | (65.9) | 334 | (78.6) | 392 | (57.9) | |||

| Don’t know | 4 | (0.4) | 1 | (0.2) | 3 | (0.4) | |||

| Unanswered question | 9 | (0.8) | 2 | (0.5) | 7 | (1.0) | |||

| RELIGION/ CULTURE/ GENDER/ SOCIO ECONOMIC |

I think that vaccinating girls against HPV encourages them to have sex | 0.0180 | |||||||

| Agree | 48 | (4.4) | 10 | (2.4) | 38 | (5.6) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 8 | (0.7) | 2 | (0.5) | 6 | (0.9) | |||

| Disagree | 1042 | (94. 6) | 413 | (97.2) | 629 | (92.9) | |||

| Don’t know | 3 | (0.3) | 0 | (0.0) | 3 | (0.4) | |||

| Unanswered question | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.1) | |||

| It is hard to talk to my daughter about her sexual health | 0.7946 | ||||||||

| Agree | 167 | (15.2) | 59 | (13.9) | 108 | (16.0) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 20 | (1.8) | 7 | (1.6) | 13 | (1.9) | |||

| Disagree | 908 | (82.4) | 356 | (83.8) | 552 | (81.5) | |||

| Don’t know | 7 | (0.6) | 3 | (0.7) | 4 | (0.6) | |||

| I feel uncomfortable discussing my daughter’s sexual health with a doctor or another health professional | 0.0766 | ||||||||

| Agree | 39 | (3.5) | 9 | (2.1) | 30 | (4.4) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 5 | (0. 5) | 2 | (0.5) | 3 | (0.4) | |||

| Disagree | 1057 | (95.9) | 413 | (97.2) | 644 | (95.1) | |||

| Don’t know | 1 | (0.1) | 1 | (0.2) | 0 | (0.0) | |||

| I have difficulty in addressing the subject of HPV vaccine with my daughter | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Agree | 56 | (5.1) | 9 | (2.1) | 47 | (6.9) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 18 | (1.6) | 1 | (0.2) | 17 | (2.5) | |||

| Disagree | 1018 | (92.4) | 415 | (97.6) | 603 | (89.1) | |||

| Don’t know | 10 | (0.9) | 0 | (0.0) | 10 | (1.5) | |||

| POLITICS/POLICIES | I am favorable to the mandatory vaccination for children under two years of age | <0.0001 <0.0001 |

|||||||

| Agree | 860 | (78.0) | 362 | (85.2) | 498 | (73.6) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 6 | (0.5) | 3 | (0.7) | 3 | (0.4) | |||

| Disagree | 232 | (21.1) | 60 | (14.1) | 172 | (25.4) | |||

| Does not know | 4 | (0.4) | 0 | (0.0) | 4 | (0.6) | |||

| Everyone should be able to choose whether or not to do vaccinate his/her children | 0.0004 | ||||||||

| Agree | 472 | (42.8) | 152 | (35.8) | 320 | (47.3) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 11 | (1.0) | 3 | (0. 7) | 8 | (1.2) | |||

| Disagree | 618 | (56.1) | 270 | (63.5) | 348 | (51.4) | |||

| Don’t know | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0. 0) | 1 | (0.1) | |||

| PERCEPTION OF THE PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRY |

The pharmaceutical industry follows strict manufacturing procedures | 0.0002 | |||||||

| Agree | 919 | (83.4) | 381 | (89. 6) | 538 | (79.5) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 20 | (1.8) | 4 | (0.9) | 16 | (2.4) | |||

| Disagree | 144 | (13.1) | 34 | (8.0) | 110 | (16.2) | |||

| Don’t know | 19 | (1.7) | 6 | (1.4) | 13 | (1.9) | |||

| INDIVIDUAL AND GROUP INFLUENCES | |||||||||

| PERSONAL, FAMILY AND OR COMMUNITY MEMBERS’ EXPERIENCE | I happened to refuse a vaccine for my daughter (or choose not to get her vaccinated) | 0.0176 | |||||||

| Yes | 301 | (27.3) | 99 | (23.3) | 202 | (29.8) | |||

| No | 801 | (72.7) | 326 | (76.7) | 475 | (70.2) | |||

| I happened to refuse a vaccine for myself (or choose not to get vaccinated) | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 379 | (34.4) | 116 | (27.3) | 263 | (38.8) | |||

| No | 723 | (65.6) | 309 | (72.7) | 414 | (61.2) | |||

| I know a person who fell seriously ill after getting vaccinated | 0.0029 | ||||||||

| Yes | 204 | (18.5) | 60 | (14. 1) | 144 | (21.3) | |||

| No | 898 | (81.5) | 365 | (85.9) | 533 | (78.7) | |||

| I know someone who became seriously ill because s/he was not vaccinated | 0.2098 | ||||||||

| Yes | 229 | (20. 8) | 99 | (23. 3) | 130 | (19.2) | |||

| No | 870 | (78.9) | 325 | (76.5) | 545 | (80.5) | |||

| Don’t know | 3 | (0.3) | 1 | (0.2) | 2 | (0.3) | |||

| Personally, I have already had abnormal pap smears for which treatment was needed (conization/surgery) | 0.3605 | ||||||||

| Yes | 199 | (18.1) | 84 | (19.8) | 115 | (17.0) | |||

| No | 902 | (81.9) | 341 | (80.2) | 561 | (82.9) | |||

| Unanswered question | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.1) | |||

| BELIEFS, ATTITUDES ABOUT HEALTH AND PREVENTION | Complementary medicine builds up the body’s own defenses, so leading to a permanent cure | 0.0004 | |||||||

| Agree | 482 | (43.7) | 154 | (36.2) | 328 | (48.4) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 38 | (3.4) | 16 | (3.8) | 22 | (3.2) | |||

| Disagree | 563 | (51.1) | 250 | (58.8) | 313 | (46.2) | |||

| Don’t know | 19 | (1.7) | 5 | (1.2) | 14 | (2.1) | |||

| I prefer that my daughter develops naturally defenses against papillomavirus rather than by vaccination | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Agree | 273 | (24.8) | 42 | (9.9) | 231 | (34.1) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 20 | (1.8) | 7 | (1.6) | 13 | (1.9) | |||

| Disagree | 793 | (72.0) | 374 | (88.0) | 419 | (61.9) | |||

| Don’t know | 16 | (1. 5) | 2 | (0.5) | 14 | (2.1) | |||

| KNOWLEDGE/AWARENESS | Have you ever searched for information on the HPV vaccine in the past? | <0.0001 | |||||||

| Yes | 537 | (48.7) | 246 | (57.9) | 291 | (43.0) | |||

| No | 565 | (51.3) | 179 | (42.1) | 386 | (57.0) | |||

| (If already researched information) Cite the 3 most consulted sources of information | |||||||||

| Attending physician | 315 | (58.7) | 161 | (65.5) | 154 | (52.9) | .0033 | ||

| Other health professional | 177 | (33.0) | 71 | (28.9) | 106 | (36.4) | 0.0632 | ||

| Internet | 403 | (75.0) | 187 | (76. 0) | 216 | (74.2) | 0.6331 | ||

| Family | 88 | (16.4) | 42 | (17.1) | 46 | (15.8) | 0.6930 | ||

| Books | 21 | (3.9) | 7 | (2.9) | 14 | (4.8) | 0.2417 | ||

| Print media | 94 | (17.5) | 41 | (16.7) | 53 | (18.2) | 0.6385 | ||

| Other | 57 | (10.6) | 26 | (10. 6) | 31 | (10.7) | 0.9749 | ||

| (If used the internet) How did you use the internet?a | |||||||||

| I went to forums | 83 | (7.5) | 30 | (16.1) | 53 | (24.5) | 0.0355 | ||

| I visited blogs | 34 | (8.4) | 9 | (4.8) | 25 | (11.6) | 0.0149 | ||

| I looked at social media | 21 | (5.2) | 6 | (3.2) | 15 | (6.9) | 0.0924 | ||

| I consulted news websites | 361 | (89. 6) | 169 | (90.4) | 192 | (88.9) | 0. 6265 | ||

| Other | 23 | (5.7) | 9 | (4.8) | 14 | (6.5) | 0.4714 | ||

| Does not know | 1 | (0.3) | 1 | (0.5) | 0 | (0.0) | 0.4640 | ||

| (If consulted information sites) Which website? | |||||||||

| Santé Publique France | 186 | (51.5) | 88 | (52.1) | 98 | (51.0) | 0.8452 | ||

| Vaccination Info Service | 107 | (29.6) | 49 | (29.0) | 58 | (30.2) | 0.8010 | ||

| Doctissimo | 256 | (70.9) | 117 | (69.2) | 139 | (72.4) | 0.5088 | ||

| Allodocteur | 72 | (19.9) | 23 | (13.6) | 49 | (25.5) | 0.0047 | ||

| Pourquoi Docteur | 5 | (1.4) | 3 | (1.8) | 2 | (1.0) | 0.6682 | ||

| Infovac | 37 | (10.3) | 17 | (10.0) | 20 | (10.4) | 0.9110 | ||

| France Info | 55 | (15.2) | 25 | (14.8) | 30 | (15.6) | 0.8262 | ||

| Le Monde | 53 | (14. 7) | 24 | (14.2) | 29 | (15.1) | 0.8089 | ||

| Le Figaro | 21 | (5.8) | 12 | (7.1) | 9 | (4.7) | 0.3284 | ||

| Alter Info | 1 | (0.3) | 1 | (0.6) | 0 | (0. 0) | 0.4681 | ||

| Alternative Santé | 50 | (13.9) | 18 | (10.7) | 32 | (16.7) | 0.0987 | ||

| Initiative Citoyenne | 12 | (3.3) | 5 | (3.0) | 7 | (3.7) | 0.7163 | ||

| Other national press | 69 | (19.1) | 31 | (18.3) | 38 | (19.8) | .7269 | ||

| Other regional press | 27 | (7.5) | 11 | (6.5) | 16 | (8.3) | 0.5108 | ||

| Other | 44 | (12.2) | 23 | (13.6) | 21 | (10.9) | 0.4387 | ||

| Does not know | 11 | (3.1) | 4 | (2.4) | 7 | (3.7) | 0.4805 | ||

| (If has already searched for information) After having had all this information, were you able to take a decision regarding the HPV vaccination? | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 434 | (80. 8) | 232 | (94.3) | 202 | (69.4) | |||

| No | 102 | (19.0) | 14 | (5.7) | 88 | (30.2) | |||

| Does not know | 1 | (0.2) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.4) | |||

| HPV is very rare | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| True | 211 | (19.1) | 47 | (11.1) | 164 | (24.2) | |||

| False | 870 | (78.9) | 375 | (88.2) | 495 | (73.1) | |||

| Does not know | 21 | (1.9) | 3 | (0.7) | 18 | (2.7) | |||

| A person could have HPV for many years without knowing it | .2073 | ||||||||

| True | 1024 | (92.9) | 402 | (94. 6) | 622 | (91. 9) | |||

| False | 69 | (6.3) | 21 | (4.9) | 48 | (7.1) | |||

| Does not know | 9 | (0.8) | 2 | (0.5) | 7 | (1.0) | |||

| Having sex at an early age increases the risk of getting HPV | 0.7527 | ||||||||

| True | 516 | (46.8) | 195 | (45. 9) | 321 | (47.4) | |||

| False | 565 | (51.3) | 223 | (52.5) | 342 | (50.5) | |||

| Does not know | 21 | (1.9) | 7 | (1.6) | 14 | (2.1) | |||

| Men cannot get HPV | 0.0909 | ||||||||

| True | 231 | (21.0) | 81 | (19.1) | 150 | (22.2) | |||

| False | 851 | (77.2) | 340 | (80.0) | 511 | (75. 5) | |||

| Does not know | 20 | (1.8) | 4 | (0.9) | 16 | (2.4) | |||

| The HPV vaccines offer protection against all sexually transmitted infections | 0.7946 | ||||||||

| True | 36 | (3.3) | 13 | (3.0) | 23 | (3.4) | |||

| False | 1058 | (96.0) | 410 | (96. 5) | 648 | (95.7) | |||

| Does not know | 8 | (0.7) | 2 | (0.5) | 6 | (0.9) | |||

| The HPV vaccines are most effective if given to people who’ve never had sex | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| True | 846 | (76.8) | 355 | (83.5) | 491 | (72.5) | |||

| False | 235 | (21.3) | 67 | (15.8) | 168 | (24.8) | |||

| Does not know | 21 | (1.9) | 3 | (0.7) | 18 | (2.7) | |||

| A person who has been vaccinated against HPV can still develop cervical cancer | 0.7852 | ||||||||

| True | 900 | (81. 7) | 346 | (81.4) | 554 | (81.8) | |||

| False | 186 | (16.9) | 74 | (17.4) | 112 | (16.6) | |||

| Does not know | 16 | (1. 5) | 5 | (1.2) | 11 | (1.6) | |||

| Girls who have been vaccinated against HPV need Pap test when they are older | 0.4247 | ||||||||

| True | 829 | (75.2) | 328 | (77.2) | 501 | (74.0) | |||

| False | 259 | (23.5) | 93 | (21.9) | 166 | (24.5) | |||

| Does not know | 14 | (1.3) | 4 | (0.9) | 10 | (1.5) | |||

| You can cure HPV by getting the HPV vaccine | .2629 | ||||||||

| True | 217 | (19.7) | 74 | (17.4) | 143 | (21.1) | |||

| False | 875 | (79.4) | 348 | (81.9) | 527 | (77.8) | |||

| Does not know | 10 | (0.9) | 3 | (0.7) | 7 | (1.0) | |||

| HPV can be transmitted through oral sex | 0.3940 | ||||||||

| True | 429 | (38.9) | 166 | (39.1) | 263 | (38.8) | |||

| False | 631 | (57.3) | 247 | (58.1) | 384 | (56.7) | |||

| Does not know | 42 | (3.8) | 12 | (2.8) | 30 | (4.4) | |||

| HPV can cause oral cancer | 0.1782 | ||||||||

| True | 209 | (19.0) | 91 | (21. 4) | 118 | (17.4) | |||

| False | 847 | (76.9) | 314 | (73.9) | 533 | (78.8) | |||

| Does not know | 46 | (4.1) | 20 | (4.7) | 26 | (3.8) | |||

| HEALTH SYSTEM AND PROVIDERS-TRUST AND PERSONAL EXPERIENCE | Please indicate to what extent you trust the following sources to tell the truth about vaccinations | ||||||||

| Pharmaceutical industry | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Trust | 562 | (51.0) | 251 | (59.1) | 311 | (45.9) | |||

| Neither trust nor distrust | 21 | (1.9) | 12 | (2.8) | 9 | (1.3) | |||

| Distrust | 514 | (46.6) | 162 | (38.1) | 352 | (52.0) | |||

| Does not know | 4 | (0.4) | 0 | (0.0) | 4 | (0.6) | |||

| Unanswered question | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.1) | |||

| Government | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Trust | 465 | (42.2) | 217 | (51.1) | 248 | (36.6) | |||

| Neither trust nor distrust | 19 | (1.7) | 10 | (2.4) | 9 | (1.3) | |||

| Distrust | 616 | (55.9) | 198 | (46.6) | 418 | (61.7) | |||

| Does not know | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.1) | |||

| Unanswered question | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.1) | |||

| Your attending physician | 0.0376 | ||||||||

| Trust | 1062 | (96.4) | 417 | (98.1) | 645 | (95. 3) | |||

| Neither trust nor distrust | 1 | (0.1) | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | |||

| Distrust | 36 | (3.3) | 7 | (1.6) | 29 | (4.3) | |||

| Does not know | 3 | (0.3) | 1 | (0.2) | 2 | (0.3) | |||

| Physicians in general | 0.0040 | ||||||||

| Trust | 1004 | (91.1) | 402 | (94.6) | 602 | (88.9) | |||

| Neither trust nor distrust | 7 | (0.6) | 1 | (0.2) | 6 | (0.9) | |||

| Distrust | 91 | (8.3) | 22 | (5.2) | 69 | (10. 2) | |||

| Pharmacists | .0003 | ||||||||

| Trust | 947 | (85.9) | 386 | (90.8) | 561 | (82.9) | |||

| Neither trust nor distrust | 13 | (1.2) | 4 | (0.9) | 9 | (1. 3) | |||

| Distrust | 141 | (12.8) | 34 | (8.0) | 107 | (15.8) | |||

| Does not know | 1 | (0.1) | 1 | (0.2) | 0 | (0.0) | |||

| Other health professionals | 0.1974 | ||||||||

| Trust | 974 | (88.4) | 384 | (90.4) | 590 | (87.1) | |||

| Neither trust nor distrust | 10 | (0.9) | 3 | (0.7) | 7 | (1.0) | |||

| Distrust | 116 | (10.5) | 37 | (8.7) | 79 | (11.7) | |||

| Does not know | 1 | (0.1) | 1 | (0.2) | 0 | (0. 0) | |||

| Unanswered question | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0. 0) | 1 | (0.1) | |||

| Scientific researchers | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Trust | 994 | (90.2) | 398 | (93.6) | 596 | (88.0) | |||

| Neither trust nor distrust | 5 | (0. 5) | 1 | (0.2) | 4 | (0.6) | |||

| Distrust | 100 | (9.1) | 26 | (6.1) | 74 | (10. 9) | |||

| Does not know | 3 | (0.3) | 0 | (0. 0) | 3 | (0.4) | |||

| Mainstream media | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Trust | 353 | (32. 0) | 166 | (39.1) | 187 | (27.6) | |||

| Neither trust nor distrust | 20 | (1.8) | 11 | (2.6) | 9 | (1.3) | |||

| Distrust | 727 | (66.0) | 248 | (58.4) | 479 | (70.8) | |||

| Does not know | 2 | (0.2) | 0 | (0. 0) | 2 | (0.3) | |||

| Alternative media | 0.1872 | ||||||||

| Trust | 240 | (21. 8) | 80 | (18.8) | 160 | (23.6) | |||

| Neither trust nor distrust | 28 | (2.5) | 14 | (3.3) | 14 | (2.1) | |||

| Distrust | 750 | (68.1) | 298 | (70.1) | 452 | (66.8) | |||

| Does not know | 83 | (7.5) | 33 | (7.8) | 50 | (7. 4) | |||

| Unanswered question | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.1) | |||

| RISK/BENEFIT (PERCEIVED/HEURISTIC) | The HPV vaccine may lead to long-term health problems | <0.0001 | |||||||

| Agree | 354 | (32.1) | 93 | (21.9) | 261 | (38.6) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 29 | (2.6) | 6 | (1.4) | 23 | (3.4) | |||

| Disagree | 676 | (61.3) | 314 | (73.9) | 362 | (53.5) | |||

| Does not know | 42 | (3.8) | 12 | (2.8) | 30 | (4.4) | |||

| Unanswered question | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.1) | |||

| There has not been enough research done on the HPV vaccine | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Agree | 321 | (29.1) | 74 | (17.4) | 247 | (36. 5) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 24 | (2.2) | 5 | (1.2) | 19 | (2.8) | |||

| Disagree | 704 | (63.9) | 335 | (78.8) | 369 | (54.5) | |||

| Does not know | 53 | (4.8) | 11 | (2.6) | 42 | (6.2) | |||

| The HPV vaccine is unsafe | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Agree | 225 | (20.4) | 46 | (10.8) | 179 | (26.4) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 19 | (1.7) | 3 | (0.7) | 16 | (2.4) | |||

| Disagree | 831 | (75.4) | 372 | (87.5) | 459 | (67.8) | |||

| Does not know | 26 | (2. 4) | 4 | (0.9) | 22 | (3. 2) | |||

| Unanswered question | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.1) | |||

| Vaccinating my daughter against HPV will help protect her against sexually transmitted infections | 0.0944 | ||||||||

| Agree | 412 | (37.4) | 170 | (40.0) | 242 | (35.7) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 7 | (0.6) | 1 | (0.2) | 6 | (0.9) | |||

| Disagree | 678 | (61.5) | 254 | (59.8) | 424 | (62.6) | |||

| Does not know | 5 | (0. 5) | 0 | (0. 0) | 5 | (0.7) | |||

| The HPV vaccine is effective in preventing HPV | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Agree | 1010 | (91.7) | 411 | (96.7) | 599 | (88.5) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 6 | (0.5) | 0 | (0. 0) | 6 | (0.9) | |||

| Disagree | 77 | (7.0) | 13 | (3.1) | 64 | (9.5) | |||

| Does not know | 9 | (0.8) | 1 | (0.2) | 8 | (1.2) | |||

| The HPV vaccine is effective in preventing genital warts | 0.3516 | ||||||||

| Agree | 404 | (36.7) | 162 | (38.1) | 242 | (35.7) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 23 | (2.1) | 5 | (1.2) | 18 | (2.7) | |||

| Disagree | 580 | (52.6) | 223 | (52. 5) | 357 | (52.7) | |||

| Does not know | 95 | (8.6) | 35 | (8.2) | 60 | (8.9) | |||

| The HPV vaccine is effective in preventing HPV-related cancers | 0.0049 | ||||||||

| Agree | 877 | (79.6) | 357 | (84.0) | 520 | (76.8) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 12 | (1.1) | 4 | (0.9) | 8 | (1.2) | |||

| Disagree | 182 | (16.5) | 60 | (14.1) | 122 | (18.0) | |||

| Does not know | 31 | (2.8) | 4 | (0.9) | 27 | (4. 0) | |||

| The use of a condom prevents the transmission of HPV infection | 0.8166 | ||||||||

| Agree | 795 | (72.1) | 312 | (73.4) | 483 | (71.3) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 4 | (0.4) | 1 | (0.2) | 3 | (0.4) | |||

| Disagree | 287 | (26.0) | 107 | (25.2) | 180 | (26.6) | |||

| Does not know | 16 | (1. 5) | 5 | (1.2) | 11 | (1.6) | |||

| The pap smear is sufficient to prevent cervical cancer | 0.1784 | ||||||||

| Agree | 581 | (52.7) | 233 | (54.8) | 348 | (51.4) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 2 | (0.2) | 0 | (0.0) | 2 | (0.3) | |||

| Disagree | 510 | (46.3) | 191 | (44.9) | 319 | (47.1) | |||

| Does not know | 9 | (0.8) | 1 | (0.2) | 8 | (1.2) | |||

| IMMUNIZATION AS A SOCIAL NORM VS. NOT NEEDED/HARMFUL | |||||||||

| My friends are getting their daughter vaccinated with the HPV vaccine | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Agree | 481 | (43.6) | 251 | (59.1) | 230 | (34.0) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 22 | (2.0) | 5 | (1.2) | 17 | (2.5) | |||

| Disagree | 442 | (40.1) | 125 | (29.4) | 317 | (46.8) | |||

| Does not know | 73 | (6.6) | 21 | (4.9) | 52 | (7.7) | |||

| Unanswered question | 84 | (7.6) | 23 | (5.4) | 61 | (9.0) | |||

| Most (other) girls around my daughter ‘s age are getting vaccinated for HPV | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Agree | 374 | (33.9) | 189 | (44.5) | 185 | (27.3) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 28 | (2.5) | 7 | (1.6) | 21 | (3.1) | |||

| Disagree | 543 | (49.3) | 186 | (43.8) | 357 | (52.7) | |||

| Does not know | 93 | (8.4) | 24 | (5.6) | 69 | (10.2) | |||

| Unanswered question | 64 | (5.8) | 19 | (4.5) | 45 | (6.6) | |||

| Doctors/health care providers believe vaccinating girls against HPV is a good idea | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Agree | 942 | (85.5) | 416 | (97.9) | 526 | (77.7) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 14 | (1.3) | 1 | (0.2) | 13 | (1.9) | |||

| Disagree | 94 | (8.5) | 7 | (1.6) | 87 | (12.9) | |||

| Does not know | 17 | (1.5) | 0 | (0.0) | 17 | (2.5) | |||

| Unanswered question | 35 | (3.2) | 1 | (0.2) | 13 | (1.9) | |||

| VACCINE/VACCINATION SPECIFIC ISSUES | |||||||||

| INTRODUCTION OF A NEW VACCINE OR NEW FORMULATION OR A NEW RECOMMENDATION FOR AN EXISTING VACCINE | The HPV vaccine is too recent so we can know if it’s safe and reliable | <0.0001 | |||||||

| Agree | 390 | (35.4) | 105 | (24.7) | 285 | (42.1) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 16 | (1.5) | 1 | (0.2) | 15 | (2.2) | |||

| Disagree | 679 | (61.6) | 315 | (74.1) | 364 | (53.8) | |||

| Does not know | 17 | (1.5) | 4 | (0.9) | 13 | (1.9) | |||

| DESIGN OF VACCINATION PROGRAM MODE OF DELIVERY | It is complicated to vaccinate my daughter against HPV because it requires 3 steps: see the doctor for the vaccine prescription, go buy the vaccine at the pharmacy, and return to the doctor for the vaccine injection | 0.1486 | |||||||

| Agree | 240 | (21. 8) | 81 | (19.1) | 159 | (23. 5) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 5 | (0. 5) | 1 | (0.2) | 4 | (0.6) | |||

| Disagree | 855 | (77.6) | 343 | (80.7) | 512 | (75.6) | |||

| Does not know | 2 | (0.2) | 0 | (0. 0) | 2 | (0.3) | |||

| It would be easier to vaccinate my daughter if the doctor had vaccines at his office for vaccinating my daughter the same day | 0.0005 | ||||||||

| Agree | 596 | (54.1) | 206 | (48.5) | 390 | (57.6) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 4 | (0.4) | 4 | (0.9) | 0 | (0.0) | |||

| Disagree | 502 | (45.6) | 215 | (50.6) | 287 | (42.4) | |||

| VACCINATION SCHEDULE | If the HPV vaccine was important, it would have been made mandatory | <0.0001 | |||||||

| Agree | 402 | (36.5) | 110 | (25.9) | 292 | (43.1) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 7 | (0.6) | 2 | (0.5) | 5 | (0.7) | |||

| Disagree | 687 | (62.3) | 310 | (72.9) | 377 | (55.7) | |||

| Does not know | 6 | (0.5) | 3 | (0.7) | 3 | (0.4) | |||

| The HPV vaccine has not been made mandatory because it is risky | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Agree | 159 | (14.4) | 33 | (7.8) | 126 | (18.6) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 19 | (1.7) | 4 | (0.9) | 15 | (2.2) | |||

| Disagree | 904 | (82.0) | 384 | (90.4) | 520 | (76.8) | |||

| Does not know | 20 | (1.8) | 4 | (0.9) | 16 | (2.4) | |||

| I think my daughter is too young to be vaccinated against HPV | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Agree | 269 | (24.4) | 17 | (4.0) | 252 | (37.2) | |||

| Neither agree nor disagree | 6 | (0.5) | 0 | (0.0) | 6 | (0.9) | |||

| Disagree | 823 | (74.7) | 408 | (96.0) | 415 | (61. 3) | |||

| Does not know | 4 | (0. 6) | 0 | (0. 0) | 4 | (0.6) | |||

| THE STRENGTH OF THE RECOMMENDATION AND/OR KNOWLEDGE BASE AND/OR ATTITUDE OF HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONALS | Has a doctor or another health professional ever recommended that you vaccinate your daughter against HPV? | <0.0001 | |||||||

| Yes | 750 | (68.1) | 373 | (87.8) | 377 | (55. 7) | |||

| No | 352 | (31.9) | 52 | (12.2) | 300 | (44. 3) | |||

| Have you asked any questions to your attending doctor about HPV vaccines? | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 639 | (58.0) | 338 | (79.5) | 301 | (44.5) | |||

| No | 462 | (41.9) | 87 | (20.5) | 375 | (55.4) | |||

| Does not know | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0. 1) | |||

| (If has already asked questions) Were you satisfied with his/her answers? | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 580 | (80.8) | 329 | (97.3) | 251 | (83.4) | |||

| No | 58 | (9.1) | 9 | (2.7) | 49 | (16.3) | |||

| Does not know | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.3) | |||

| (If has already asked questions) Was your attending physician hesitant regarding the vaccine? | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 40 | (6.3) | 4 | (1.2) | 36 | (12.0) | |||

| No | 596 | (93.3) | 333 | (98.5) | 263 | (87.4) | |||

| Does not know | 2 | (0.3) | 1 | (0.3) | 1 | (0.3) | |||

| Unanswered question | 1 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 1 | (0.3) | |||

aTotals exceed 100% because multiple responses were coded per participant.

bQuestion answered by the mothers who heard about the HPV vaccine (n = 1068.

Contextual factors

Communication and media environment

The most frequent sources through which mothers had heard about HPV vaccination were the recommendation of their attending physician (44. 6%), the Television (24.1%), and the recommendation of a gynecologist (21.1%). Mothers with vaccinated daughters heard more frequently about HPV through a recommendation from their attending physician and gynecologist than mothers of unvaccinated daughters (p < 0.0001 and p = 0.0066, respectively). Mothers of vaccinated daughters heard less frequently about HPV through Television than mothers of unvaccinated daughters (p = 0.0109).

Historical influences

Nearly a third of the respondents agreed with the statement that “Since the controversy over vaccination against H1N1 flu, I have less confidence in French vaccination recommendations” and that “Since the controversy over the hepatitis B vaccine, I have less confidence in the healthcare system” (31.6% and 31.8%, respectively). The percentage of agreement with those statements was lower among mothers of vaccinated daughters (p < 0.0001 for both).

Religion/culture/gender/socioeconomic factors

The majority of respondents disagreed that vaccinating girls against HPV encourages them to have sex (94.6%), that is hard to talk to them about their sexual health (82.4%), that they have difficulty in addressing the subject of HPV vaccine with them (92.4%) and that they feel uncomfortable discussing their daughter’s sexual health with a doctor or another health professional (95.9%). Significant differences were observed between the mothers of vaccinated daughters and mothers of unvaccinated daughters in the statement “I think that vaccinating girls against HPV encourages them to have sex” and “I have difficulty in addressing the subject of HPV vaccine with my daughter” with a percentage of agreement higher in the group of mothers of unvaccinated daughters (p = 0.0180 and p < 0.0001, respectively).

Politics/policies

Nearly a fifth (21.1%) of respondents disagreed with the statement that they favored compulsory vaccination for children under the age of two, and less than half (42.8%) agreed that everyone should be able to choose whether or not to vaccinate their children. Significant differences were observed between the mothers of vaccinated and unvaccinated daughters for those two statements: agreement with the statement of compulsory vaccination was higher among mothers of vaccinated daughters (p < 0.0001), while the agreement with the second statement was lower among mothers of vaccinated daughters (p = 0.0004).

Perception of the pharmaceutical industry

The majority (83.4%) of respondents agreed that the pharmaceutical industry follows strict manufacturing procedures, with a significantly higher proportion of mothers of vaccinated daughters agreeing (p = 0.0002).

Individual and group factors

Personal, family, and or community members’ experiences

Nearly a third of respondents (34.4%) indicated having refused a vaccine for themselves (or chose not to get vaccinated), and fewer (27.3%) refused a vaccine for their daughter (or chose not to get her vaccinated). Nearly a fifth (18.5%) of respondents stated that they knew a person who fell seriously ill after getting vaccinated, that they knew someone who became seriously ill because s/he was not vaccinated (20.8%), and that they already had abnormal pap smears for which treatment was needed (18.1%). The HPV vaccine uptake was lower in the group of mothers who previously refused a vaccine for themselves (p < 0.0001) and their daughters (p = 0.0176) and who knew a person who fell seriously ill after getting vaccinated (p = 0.0029).

Beliefs and attitudes about health and prevention

Nearly half (43.7%) of the respondents agreed that complementary medicine builds up the body’s defenses leading to a permanent cure, and nearly a quarter (24.8%) preferred that their daughter developed natural defenses against HPV rather than through vaccination. The percentage of agreement with those statements was significantly higher in the mothers of unvaccinated daughters (p = 0.0004 and p < 0.0001, respectively).

Knowledge/awareness

Nearly half (48.7%) of respondents had already searched for information on the HPV vaccine; the most frequent source of information had been the Internet (75.0%), followed by their attending physicians (58.7%) and other health professionals (33.0%). The vast majority of mothers who searched for information on the Internet consulted news websites (89.6%), of whom nearly three-quarters (70.9%) reported consulting Doctissimo (a website dealing with health and well-being-related topics). Just over half (51.5%) of mothers who searched the Internet for information on HPV vaccine reported consulting the Santé Publique France website (the official French national public health agency website), and fewer than a third (29.6%) reported consulting Vaccination Info Service, a service linked to Sante Publique France. After having consulted the information, the majority of the mothers declared this helped them decide on HPV vaccination of their daughters (80.8%). Significant differences were observed between the mothers of vaccinated and unvaccinated daughters, with a higher rate of information search among mothers of vaccinated daughters (p < 0.0001). Significant differences were observed between the mothers of vaccinated and unvaccinated daughters, with a higher rate of mothers of vaccinated daughters being able to take a decision regarding the HPV vaccination after having searched for information (p < 0.0001).

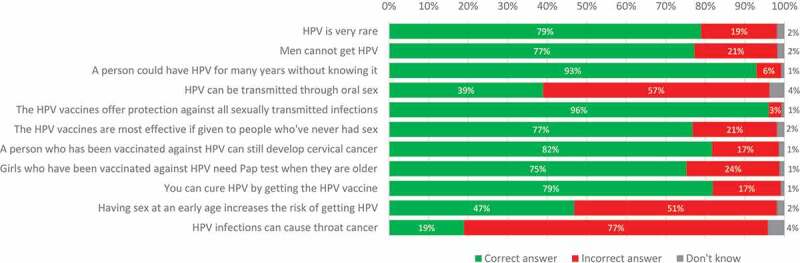

Proportion of correct answers

The highest proportions of incorrect answers to general HPV knowledge were for the questions of HPV as a cause of oral cancer (76.9%), whether HPV can be transmitted through oral sex (57.3%), and whether having sex at a young age increases the risk of HPV infection (51.3%). The highest proportions of correct answers were for the questions of whether the HPV vaccine protects against all sexually transmitted infections (96.0%), whether a person can be infected with HPV for many years without knowing (92.9%), and whether a person who has been vaccinated against HPV can still develop cervical cancer (81.7%) (Figure 3). Significant differences were observed between the mothers of vaccinated daughters and mothers of unvaccinated daughters for the statement “HPV is very rare” and “HPV vaccines are most effective if given to people who never had sex,” with a higher rate of correct answers in mothers of vaccinated daughters (p < 0.0001).

Figure 3.

Proportion of correct answers.

Health system and providers trust. The most trusted source of information about vaccination was their attending physician (96.4%), physicians in general (91.1%), and researchers (90.2%). By contrast, less than half of the respondents trusted the government (42.2%). Significant differences were observed between the mothers of vaccinated daughters and mothers of unvaccinated daughters with a higher trust in the pharmaceutical industry (p < 0.0001), the government (p < 0.0001), their attending physician (p = 0.0376), physicians in general(p = 0.004), pharmacists (p = 0.0003), researchers, and mainstream media (p < 0.0001) among mothers of vaccinated daughters.

Risks and benefits (perceived/heuristic)

Nearly a third (32.1%) of respondents agreed with the statement that the HPV vaccine may lead to long-term health problems and that there has not been enough research done on this vaccine (29.1%). Around a fifth (20.4%) agreed with the statement that the HPV vaccine was unsafe. Significant differences were observed between the mothers of vaccinated and unvaccinated daughters with a higher rate of disagreement with the statements “The HPV vaccine may lead to long-term problems“(p < 0.0001), “There has not been enough research done on the HPV vaccine” (p < 0.0001), “The HPV vaccine is unsafe” (p < 0.0001) among mothers of vaccinated daughters.

The majority of respondents agreed with the statement that the HPV vaccine was effective in preventing HPV (91.7%) and HPV-related cancers (79.6%), while less than 40% of respondents agreed with the statement that the HPV vaccine was effective in preventing genital warts (36.7%). Just over half of respondents (52.7%) agreed with the statement that the Pap smear was sufficient to prevent cervical cancer. Higher rates of agreement with the statements “the HPV vaccine is effective in preventing HPV” (p < 0.0001) and “the HPV vaccine is effective in preventing HPV-related cancers” (p = 0.0049) were found among mothers of vaccinated daughters.

Immunization as a social norm vs. not needed/harmful

The vast majority of respondents (85.5%) agreed with the statement that doctors/health care providers believe vaccinating girls against HPV is a good idea. Less than half of respondents (43.6%) agreed with the statements that their friends were getting their daughter vaccinated with the HPV vaccine and that most (other) girls around their daughter’s age were getting vaccinated for HPV (34.0%). Significant differences were observed between the mothers of vaccinated daughters and mothers of unvaccinated daughters, with a higher rate of agreement in the group of mothers of vaccinated daughters (p < 0.0001).

Vaccine/vaccination specific factors

Introduction of a new vaccine or a new formulation or a new recommendation for an existing vaccine

Over a third of respondents (35.4%) agreed with the statement that the HPV vaccine was too recent, so we can know if it is safe and reliable, with a significantly lower rate of agreement among the mothers of unvaccinated daughters (p < 0.0001).

Design of vaccination program/mode of delivery

More than half of respondents (54.1%) agreed with the statement that it would be easier to vaccinate their daughter if the doctor had vaccines at their office for same-day vaccination, although only a fifth (21.8%) agreed that it was complicated to vaccinate their daughter against HPV because it required three steps: see the doctor for the vaccine prescription, buy the vaccine at the pharmacy and return to the doctor for the vaccine injection. There was a significantly higher percentage of agreement regarding the same-day vaccination among mothers of unvaccinated daughters (p = 0.0005).

Vaccination schedule

Over a third of respondents (36.5%) agreed that if the HPV vaccine were important, it would have been made mandatory, with just under a quarter (24.4%) agreeing with the statement that their daughter was too young to be vaccinated against HPV, and 14.4% agreeing that the HPV vaccine had not been made mandatory because it was risky. Significant differences were observed between the mothers of vaccinated daughters and mothers of unvaccinated daughters, with a lower percentage of agreement with those statements among mothers of vaccinated daughters (p < 0.0001).

The strength of the recommendation and/or knowledge base and/or attitude of healthcare professionals

Nearly 70% (68.1%) of respondents have been recommended the HPV vaccine by a doctor or another health professional; 58% have asked questions to their attending physician about HPV vaccination, and the vast majority (90.8%) were satisfied with the answers. About 6.3% of the physicians who answered the mothers’ questions were hesitant about HPV vaccination. Significant differences were observed between the mothers of vaccinated daughters and mothers of unvaccinated daughters for all those statements, with a higher rate of healthcare professional recommendation and questions asked about HPV vaccines among mothers of vaccinated daughters (p < 0.0001).

Factors associated with HPV vaccination uptake

Table 4 shows the results of the multivariate analysis of maternal answers associated with HPV vaccination uptake in their daughters. The multivariate analysis revealed that agreeing with the statement that doctors/health care providers believe vaccinating girls against HPV was a good idea, and having asked questions to the attending doctor about HPV vaccines were associated with a higher HPV vaccine uptake among their daughters (OR = 4.99, 95% CI [2.09–11.89]; and OR = 3.44, 95% CI [2.40–4.92]). The mother’s belief that her daughter was too young to be vaccinated against HPV (OR = 0.16, 95% CI [0.09–0.29]) and a lower daughter’s age (OR = 0.17, 95% CI [0.10–0.28] for girls aged 11 compared to those aged 14) were found to be strongly inversely associated with HPV vaccination, followed by agreeing with the statement that the HPV vaccine was unsafe (OR = 0.42 , 95% CI [0.26–0.67]), identifying as true the statement that HPV was very rare (OR = 0.49 , 95% CI [0.31–0.77]), and the mother’s refusal of own vaccination (OR = 0.57, 95% CI [0.40–0.80]) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Logistic regression multivariable model showing covariates independently associated with receiving at least one dose of HPV vaccine.

| Adjusted odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Daughter’s age | 11 | 0.17 | 0.10–0.28 |

| 12 | 0.24 | 0.16–0.38 | |

| 13 | 0.50 | 0.33–0.76 | |

| 14 | Reference | - | |

| I happened to refuse a vaccine for myself (or choose not to get vaccinated) | Yes | 0.57 | 0.40–0.80 |

| No | Reference | - | |

| HPV is very rare | True | 0.49 | 0.31–0.77 |

| False | Reference | - | |

| The HPV vaccine is unsafe | Agree | 0.42 | 0.26–0.67 |

| Disagree | Reference | - | |

| Doctors/health care providers believe vaccinating girls against HPV is a good idea | Agree | 4.99 | 2.09–11.89 |

| Disagree | Reference | - | |

| - | |||

| I think my daughter is too young to be vaccinated against HPV | Agree | 0.16 | 0.09–0.29 |

| Disagree | Reference | - | |

| Have you asked any questions to your attending doctor about HPV vaccines? | Yes | 3.44 | 2.40–4.92 |

| No | Reference | - |

Discussion

Low HPV vaccination uptake in teenage girls is a public health concern in France. We conducted a nationwide telephone survey to document the determinants of this uptake. To our knowledge, this is the first telephone survey to report the determinants of HPV vaccination uptake in France. It is also the first based on the WHO model exploring vaccine hesitancy18 adapted to the French context.2 In this study, 38.6% of eligible teenage girls were reported to have been vaccinated against HPV. This is consistent with the latest national one-dose HPV vaccination coverage estimate of 40.7% (reported for the year 2020) for girls aged 15 years,6 considering that the oldest girls in our study were 14 years old.

Agreeing with the statement that doctors/health care providers believe vaccinating girls against HPV was a good idea, and having asked questions to the attending doctor about HPV vaccination were the most influential factors for the decision of getting the daughters vaccinated against HPV. On the other hand, believing that their daughter was too young to be vaccinated against HPV and their daughter’s actual age were the most influential factors concerning the decision of not getting the daughters vaccinated. These data confirm other studies demonstrating the influencing role of health care professionals in mothers’ decision-making,14,26 as well as the influence of the child’s age.27,28 Similar to previous studies, we found that mothers harboring HPV vaccine safety concerns were less likely to get their daughters vaccinated,29 in particular among mothers who previously refused a vaccine for themselves.30

Although most knowledge items were answered correctly by at least 75% of the mothers, the level of knowledge regarding the oral transmission of HPV infection and association with oral cancers were low. Of note, less than half of respondents correctly answered the question about the risk of HPV infection associated with a younger sexual debut.

Strengths and limitations

Our study had several strengths, including the representativeness of the study sample using the quota recruitment strategy, the phone survey methodology allowing reaching a large population quite rapidly, and the use of a survey instrument on HPV vaccine hesitancy adapted to the French context.2 Some limitations should be considered. First, the survey findings might not be generalizable. Second, no record verification was performed in this study to ascertain the daughters’ HPV vaccination status or administration of earlier childhood vaccines. However, the parental interview is a common method of measuring vaccination status in adolescents, and recall bias is likely limited as the survey was conducted close to the age recommended for HPV vaccination. Furthermore, only one other vaccine is currently recommended for the French adolescent general population (diphtheria-tetanus-acellular pertussis-inactivated polio), except catch-up vaccinations. Third, our sample was constituted only of mothers. While it would have been interesting to also include fathers’ opinions, in the vast majority of cases, mothers have the primary decision-making power about HPV vaccination, as is usually the case regarding their daughters’ overall reproductive health matters.31–33 Fourth, an inherent weakness of self-reporting is social desirability, which tends to give answers that are thought to be more socially acceptable.

Practical implications

Our study findings have practical implications for designing interventions to increase HPV vaccine uptake in France. They point to the essential role of health care providers in influencing HPV vaccination. Health care providers, family doctors, in particular, have a strong normative function and are trusted by the population, and mothers should be encouraged to seek advice from them. This could be achieved by introducing a consultation offered to mothers of girls turning 11, where they would be offered the opportunity for counseling by their attending physician about the importance of vaccinating their daughter at that age against a virus that is very common, with a vaccine that has been proven to be safe. Mothers who have already refused a vaccine for themselves could be particularly targeted. Such dedicated HPV prevention-focused-visit could also be used to raise awareness about the oral transmission of HPV and the risk of oral cancer. Moreover, our survey reveals that less than 70% of the mothers have been recommended the HPV vaccine by a physician or another health professional, so there is room for improvement. This emphasizes the importance of training to improve health professional recommendation of HPV vaccination as well as accurate and consistent messaging about the efficacy of HPV vaccines. In addition, our findings can also inform communication campaigns to address public awareness and knowledge about HPV, its link with cancers, and its prevention.

Conclusion

We have identified important determinants associated with HPV vaccine uptake in France. Interventions designed to improve HPV vaccine uptake should be tailored to address these determinants; in particular, the role of health care providers should be reemphasized, and wrong beliefs about the daughter’s age concerning the need for HPV vaccination should be corrected by relevant communication strategies.

Acknowledgments

We thank the respondents who participated in the phone survey.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by a PhD fellowship from the French National Institute of Cancer awarded to FD and a grant from Merck Investigator Studies Program. The other authors received no specific funding for this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Author’s contributions

FD, PC and OL had designed the study. FD had performed the data analysis, the redaction of the manuscript, and the revision process of this paper. IPSOS have participated in the revision process and the redaction of the manuscript. All authors have approved the final manuscript. All authors have approved the final manuscript. MSD had no role in the design of the study or the writing of the manuscript.

Ethical approval statement

This study was approved by the French Institute of Health Data (INDS: Institut National des Données de Santé) as an observational study (category MR-4 of Jardé law), and its database was authorized by the French National Committee for Data Protection (CNIL) (n° 920031), dated 11/12/2020). The Ethics Committee of Inserm also approved this study. Participants received General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) mentions and were informed about their right to anonymization, confidentiality, and withdrawal from the study with no adverse consequences.

References

- 1.The French National Cancer Institute . Cancers in France. [accessed 2021 Nov 14]. https://www.e-cancer.fr/ressources/cancers_en_france/#page=117

- 2.Bruni L, Albero G, Serrano B, Mena M, Collado JJ, Gómez D, Muñoz J, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S.. ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre). Human papillomavirus and related diseases in France. Summary report. ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre); 2021. [accessed 2022 May 2]. https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/FRA.pdf

- 3.The World Health Organization (WHO) . 73rd World Health Assembly Decisions. 2020. Aug 7 [accessed 2022 May 2]. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/73rd-world-health-assembly-decisions

- 4.The French Ministry of Health . The vaccination schedule. [accessed 2021 Nov 14]. https://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/prevention-en-sante/preserver-sa-sante/vaccination/calendrier-vaccinal

- 5.The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) . Vaccine scheduler. 2021 Oct 28 [accessed 2022 May 2]. https://vaccine-schedule.ecdc.europa.eu/Scheduler/ByCountry?SelectedCountryId=76&IncludeChildAgeGroup=true&IncludeChildAgeGroup=false&IncludeAdultAgeGroup=true&IncludeAdultAgeGroup=false

- 6.The French Public Health Agency . Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination coverage data by age group. 2022. Apr 25 [accessed 2021 Nov 14]. https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/determinants-de-sante/vaccination/donnees-de-couverture-vaccinale-papillomavirus-humains-hpv-par-groupe-d-age

- 7.The French National Cancer Institute . Cancer plan 2014-2019: curing and preventing cancer: let’s give everyone the same chance, everywhere in France. 2015. [accessed 2022 Apr 19]. https://www.e-cancer.fr/Expertises-et-publications/Catalogue-des-publications/Plan-Cancer-2014-2019

- 8.The French High Council for Public Health (HCSP) . Summary report of the first mandate of the French High Council for Public Health. 2009. Dec 11 [accessed 2018 Jan 21]. https://www.hcsp.fr/Explore.cgi/avisrapportsdomaine?clefr=97

- 9.The French National Authority for Health (HAS) . Cervical cancer: better vaccination coverage and increased screening remain the priority. 2017. Oct 11 [accessed 2018 Jan 28]. https://www.has-sante.fr/portail/jcms/c_2797450/fr/cancer-du-col-de-l-uterus-une-meilleure-couverture-vaccinale-et-un-depistage-renforce-restent-la-priorite

- 10.Decree No. 2019-712 of 5 July 2019 on the experiment for the development of vaccination against human papillomavirus infections - legifrance. [accessed 2022 May 5]. https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/LEGITEXT000038736248/

- 11.Kessels SJM, Marshall HS, Watson M, Braunack-Mayer AJ, Reuzel R, Tooher RL. Factors associated with HPV vaccine uptake in teenage girls: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2012;30(24):1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernández de Casadevante V, Gil Cuesta J, Cantarero-Arévalo L. Determinants in the uptake of the human papillomavirus vaccine: a systematic review based on European studies. Front Oncol. 2015;5:141. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spencer JC, Calo WA, Brewer NT. Disparities and reverse disparities in HPV vaccination: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2019;123:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newman PA, Logie CH, Lacombe-Duncan A, Baiden P, Tepjan S, Rubincam C, Doukas N, Asey F. Parents’ uptake of human papillomavirus vaccines for their children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e019206. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guthmann J-P, Pelat C, Célant N, Parent du Chatelet I, Duport N, Rochereau T, Lévy-Bruhl D. Socioeconomic inequalities to accessing vaccination against human papillomavirus in France: results of the health, health care and insurance survey, 2012. Revue D’Epidemiologie Et De Sante Publique. 2017;65(2):109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.respe.2017.01.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Héquet D, Rouzier R, Grce M. Determinants of geographic inequalities in HPV vaccination in the most populated region of France. PloS One. 2017;12(3):e0172906. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lutringer-Magnin D, Cropet C, Barone G, Canat G, Kalecinski J, Leocmach Y, Vanhems P, Chauvin F, Lasset C. HPV vaccination among French girls and women aged 14-23 years and the relationship with their mothers’ uptake of pap smear screening: a study in general practice. Vaccine. 2013;31(45):5243–5249. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Schulz WS, Chaudhuri M, Zhou Y, Dube E, Schuster M, MacDonald NE, Wilson R. Measuring vaccine hesitancy: the development of a survey tool. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4165–4175. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guzman-Holst A, DeAntonio R, Prado-Cohrs D, Juliao P. Barriers to vaccination in Latin America: a systematic literature review. Vaccine. 2020;38(3):470–481. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.10.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacDonald NE. SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy . Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4161–4164. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies . Tables of the French economy. 2014. Feb 19 [accessed 2021 Nov 14]. https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/1288326?sommaire=1288404

- 22.Tatar O, Shapiro GK, Perez S, Wade K, Rosberger Z. Using the precaution adoption process model to clarify human papillomavirus vaccine hesitancy in Canadian parents of girls and parents of boys. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 2019 Feb 8;15(7–8):1803–1814. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1575711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shapiro GK, Tatar O, Amsel R, Prue G, Zimet GD, Knauper B, Rosberger Z. Using an integrated conceptual framework to investigate parents’ HPV vaccine decision for their daughters and sons. Prev Med. 2018;116:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larson HJ, de Figueiredo A, Xiahong Z, Schulz WS, Verger P, Johnston IG, Cook AR, Jones NS. The state of vaccine confidence 2016: global insights through a 67-country survey. EBioMedicine. 2016;12:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, Holford TR, Feinstein AR. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(12):1373–1379. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Derhy S, Gaillot J, Rousseau S, Piel C, Thorrington D, Zanetti L, Gall B, Venot C, Chyderiotis S, Mueller J. [Extension of HPV vaccination to boys: survey of families and general practitioners]. Bull Cancer. 2022. ;109(4):S0007455122000364. doi: 10.1016/j.bulcan.2022.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, Bish CL, Stokley SK. Human papillomavirus vaccination estimates among adolescents in the Mississippi delta region: National Immunization Survey ‑ Teen, 2015–2017. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:190234. doi: 10.5888/pcd17.190234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bodson J, Ding Q, Warner EL, Hawkins AJ, Henry KA, Kepka D. Sub-Regional assessment of HPV vaccination among female adolescents in the Intermountain West and implications for intervention opportunities. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(7):1500–1511. doi: 10.1007/s10995-017-2274-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karafillakis E, Simas C, Jarrett C, Verger P, Peretti-Watel P, Dib F, De Angelis S, Takacs J, Ali KA, Pastore Celentano L, et al. HPV vaccination in a context of public mistrust and uncertainty: a systematic literature review of determinants of HPV vaccine hesitancy in Europe. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, [2019 Jan 11];15(7–8):1615–1627. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1564436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kornides M, Head KJ, Feemster K, Zimet GD, Panozzo CA. Associations between HPV vaccination among women and their 11–14-year-old children. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics. 2019;15(7–8):1824–1830. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1625642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hertweck SP, LaJoie AS, Pinto MD, Flamini L, Lynch T, Logsdon MC. Health care decision making by mothers for their adolescent daughters regarding the quadrivalent HPV vaccine. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26(2):96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kahn JA, Ding L, Huang B, Zimet GD, Rosenthal SL, Frazier AL. Mothers’ intention for their daughters and themselves to receive the human papillomavirus vaccine: a national study of nurses. Pediatrics. 2009;123(6):1439–1445. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allen JD, de Jesus M, Mars D, Tom L, Cloutier L, Shelton RC. Decision-Making about the HPV vaccine among ethnically diverse parents: implications for health communications. Journal of Oncology. 2012;2012:401979. doi: 10.1155/2012/401979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]