Abstract

Introduction

Radiation-induced lung injury (RILI) is one of the most clinically-challenging toxicities and dose-limiting factors during and/or after thoracic radiation therapy for oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). With limited effective protective drugs against RILI, the main strategy to reduce the injury is strict adherence to dose-volume restrictions of normal lungs. RILI can manifest as acute radiation pneumonitis with cellular injury, cytokine release and cytokine recruitment to inflammatory infiltrate, and subsequent chronic radiation pulmonary fibrosis. Pirfenidone inhibits the production of inflammatory cytokines, scavenges-free radicals and reduces hydroxyproline and collagen formation. Hence, pirfenidone might be a promising drug for RILI prevention. This study aims to evaluate the efficacy and safety of pirfenidone in preventing RILI in patients with locally advanced ESCC receiving chemoradiotherapy.

Methods and analysis

This study is designed as a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blinded, single-centre phase 2 trial and will explore whether the addition of pirfenidone during concurrent chemoradiation therapy (CCRT) could prevent RILI in patients with locally advanced ESCC unsuitable for surgery. Eligible participants will be randomised at 1:1 to pirfenidone and placebo groups. The primary endpoint is the incidence of grade >2 RILI. Secondary endpoints include the incidence of any grade other than grade >2 RILI, time to RILI occurrence, changes in pulmonary function after CCRT, completion rate of CCRT, disease-free survival and overall survival. The follow-up period will be 1 year. In case the results meet the primary endpoint of this trial, a phase 3 multicentre trial with a larger sample size will be required to substantiate the evidence of the benefit of pirfenidone in RILI prevention.

Ethics and dissemination

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fujian Union Hospital (No. 2021YF001-02). The findings of the trial will be disseminated through peer-reviewed journals, and national and international conference presentations.

Trial registration number

ChiCTR2100043032.

Keywords: adult oncology, radiation oncology, adult radiotherapy, radiation oncology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first randomised controlled trial to explore the efficacy and safety of pirfenidone in radiation-induced lung injury prevention.

It is a double-blinded trial where neither patients nor physicians will know the treatment allocation.

It is a phase 2 trial performed at a single centre.

The dosage of radiation is usually inconsistent, with patients with unresectable locally advanced oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma receiving 50 Gy to 60 Gy, and cases in the process of downstaging receiving 40 Gy due to further option of surgical resection.

Introduction

Oesophageal cancer is the eighth most common cancer worldwide. Of the 477 900 new cases reported globally per year, nearly half occur in China, and 90% of them are oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC).1 The definitive standard of care for unresectable locally advanced ESCC remains concurrent chemoradiation therapy, with a 3-year overall survival (OS) rate of 30%–37%.2–5 Because the lungs often lay in the path of treatment radiation beams, radiation-induced lung injury (RILI) is inevitable. RILI is one of the most common side effects and potentially dose-limiting toxicities of radiotherapy for oesophageal cancer, with an incidence of about 10.7%–35.14%.6–11 Furthermore, RILI during radiation can delay or even interrupt radiotherapy, resulting in poor local control of the disease, increased financial burden and even death.

Although advanced radiotherapeutic technologies such as intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) are superior to traditional two-dimensional and three-dimensional conformal radiation therapies regarding dosimetry and organ protection,10 12 many patients still develop varying degrees of RILI.13 In clinical practice, there is no specific treatment for RILI except oxygen inhalation, glucocorticoid administration and the application of antibiotics when necessary. Therefore, preventing RILI is of greater clinical significance than treating it. Although amifostine was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for radiotherapy protection, it does not efficiently protect against RILI during oesophageal cancer treatment.14 15 Moreover, its clinical application is limited because of high cost and frequent side effects. Therefore, few effective protective strategies against RILI during radiotherapy are available for patients with ESCC.

Pirfenidone is an active small-molecule oral drug that inhibits transforming growth factor-β1 overexpression and reduces the secretion of platelet-derived growth factor and fibroblast growth factor, thereby suppressing the biological activity of fibroblasts.16–18 Pharmacodynamic studies have demonstrated pirfenidone exerts satisfactory effects in lung inflammation and fibrosis.19–22 The FDA approved pirfenidone in 2014 for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF),23 24 which shares some pathological manifestations with RILI.25 26 A previous study in mice showed that pirfenidone attenuates RILI.27 A phase 2 trial is in the recruitment stage and aims to confirm the efficacy of pirfenidone in the treatment of RILI (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03902509).

There are no published clinical data to assess the prophylactic role of pirfenidone in RILI. Therefore, this randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blinded, single-centre, phase 2 trial is designed to examine whether pirfenidone could reduce the occurrence of RILI in patients with locally advanced ESCC administered concurrent chemoradiation therapy (CCRT).

Methods

Study design and participants

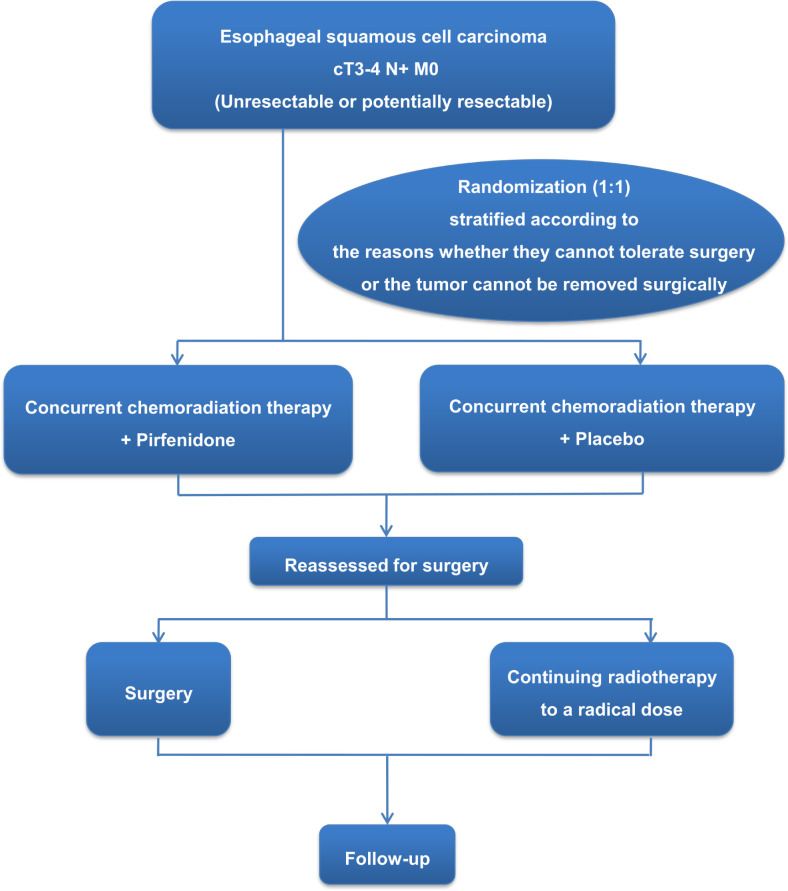

This is a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blinded, single-centre, phase 2 clinical trial to examine the potential of pirfenidone in preventing RILI in patients with unresectable locally advanced ESCC at diagnosis administered CCRT. The participants will be randomised at 1:1 to the pirfenidone and control groups. Figure 1 depicts the overview of the study procedure.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study procedure.

The detailed inclusion, exclusion and withdrawal criteria are listed in table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion, exclusion and withdrawal criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Withdrawal criteria |

|

|

|

AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ESCC, oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

All eligible patients should provide written informed consent and be willing to participate in and complete the study, including follow-up.

Pretreatment assessment and screening

Each patient must complete the following examinations and undergo counselling within 1 or 2 weeks before the onset of the trial:

Detailed medical history review.

Physical examinations to record height, weight, vital signs and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status.

Blood tests, including complete blood count (CBC), serum biochemistry, coagulation function, hepatitis B virus (HBV) and HBV DNA (for HBsAg-positive patients), and oesophageal cancer-related tumour markers such as carcinoembryonic antigen, cancer antigen (CA) 199, CA125, CA153, neuron-specific enolase, squamous cell carcinoma antigen, soluble fragment of cytokeratin 19 and α-fetoprotein.

Cardiopulmonary function evaluation, including electrocardiography, ultrasonic cardiography and pulmonary function assessment.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and biopsy.

Imaging, including chest/abdominal CT with intravenous contrast and upper gastrointestinal swallowed meglumine diatrizoate contrast, pelvic CT with contrast as clinically indicated and [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT (FDG-PET/CT) if accepted by the patient, leading to more accurate staging.

Nutritional assessment and counselling.

Smoking cessation counselling.

Radiotherapy

The target contour principle is as follows. Gross tumour volume (GTV) includes the primary tumour (GTVp) and enlarged regional lymph nodes (GTVn), determined by CT simulation scan and other diagnostic imaging methods. Elective node irradiation (ENI) will be used for clinical target volume (CTV) delineation. CTV of GTVp is defined as primary tumour volume plus a superior–inferior 3 cm margin expansion and a 0.5–1 cm radial expansion including paraoesophageal lymph nodes. CTV of GTVn will cover all the lymph nodes involved and high-risk lymphatic drainage regions such as the supraclavicular region for super-thoracic and middle-thoracic sections.28 Planning target volume (PTV) for GTV and CTV will be created by expanding with a uniform margin of 0.5 cm separately. The recommended doses for PTV–CTV and PTV–GTV are 50.4 Gy/1.8 Gy/28 fractions and 60 Gy/1.8 Gy/33 fractions, respectively. If the target area is large and organs at risk cannot be achieved, only PTV–GTV irradiation or PTV–CTV irradiation can be performed as determined by the treating radiotherapist. The administered dose should cover at least 95% of the PTV. Normal tissue tolerance dose limits are listed in table 2. All patients will be positioned supine on the treatment couch and fixed with a custom-fitted thermoplastic sheet, and setup imaging will be acquired every day before treatment to correct the treatment position by the On-board imaging image system. IMRT is recommended when the treatment plans are designed. Dose calculation for areas with artefacts generates heterogeneity, leading to high dose deviation. To ensure the quality of the radiotherapy delivered, the Acuros XB (V.15.5) dose algorithm that was reported to be as accurate as or close to the Monte Carlo simulation method will be employed in this present study. The treatment plan for all patients will be verified using the Delta4 Phantom, and the gamma passing rate at the criteria of 3%/3 mm will be greater than 98%.

Table 2.

Dose limits for organs at risk (OAR)

| OAR | Normal tissue dose-volume constraints |

| Lung | V20≤28%–30%, V5≤60%; MLD<15 Gy |

| Heart | V40<30%, V40≤30%; mean≤30 Gy |

| Spinal cord | Max≤45 Gy |

| Stomach | V40<40%, max≤55–60 Gy |

| Liver | V30<40%; mean≤25 Gy |

MLD, mean lung dose; Vxx, % of the whole OAR receiving ≥xx Gy.

Resectability will be reassessed by a multidisciplinary team at irradiation with 41.4 Gy. If surgical resection is possible, radiation therapy will be discontinued and surgery will be performed 4–8 weeks after radiation termination.

Chemotherapy

The participants will receive docetaxel at 60 mg/m2 intravenously on day 1 and cisplatin at 30 mg/m2 intravenously on days 1 and 2 for two cycles. Polyethylene glycol recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor is recommended for the prevention of neutropenia during CCRT. Dose modification will be based on the preceding cycle’s CBC data and biochemical markers. Chemotherapy will be continued with: (1) absolute neutrophil count ≥1.5×109/L; (2) platelet count ≥100×109/L; (3) grade <2 alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase and total bilirubin based on Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) criteria; (4) non-haematological toxicity (except for hair loss) returning to grade 1 or baseline level. The doses of both drugs will be decreased by 20% in case of any grade 3 or higher toxicities. In case of grade 3 or 4 radiation pneumonitis, radiotherapy and concurrent chemotherapy will be terminated.

Randomisation and intervention

The participants will be randomised at 1:1 to the pirfenidone or control groups using a random number table and stratified based on tolerability or ineligibility to surgery. Participants and doctors will be blinded to treatment allocation. Identical pirfenidone and placebo capsules will be provided by Beijing Continent Pharmaceutical. The appearance, smell, taste and properties of the placebo are the same as those of the study drug. Each capsule contains 100 mg of drug or placebo. In the first week, the dosage will be 200 mg/time, three times/day. In the second week, the dosage will be increased to 300 mg/time, three times/day. In weeks 3–12, the dosage will be further increased to 400 mg/time, three times/day. Pirfenidone treatment will start on the day of radiotherapy initiation and last for 12 weeks. The capsules will be taken during or after meals as gastrointestinal reactions are the most common adverse effects of pirfenidone. Photosensitivity is another common adverse event. External use of sunscreen and avoiding the sun during medication can effectively reduce the incidence and severity of photosensitivity reactions. In case adverse events still occur or cannot be tolerated even after dose reduction, the drug will be temporarily discontinued for 1–2 weeks until the participant tolerates the symptoms. Once adverse events are alleviated or can be tolerated, the participant will retake pirfenidone. The physician can decide whether to stop the drug treatment according to the situation. Pirfenidone treatment will be permanently discontinued in case of severe adverse events, including liver dysfunction, jaundice, severe hypersensitivity and photosensitivity.

Concomitant medication

Drugs that may prevent or treat fibrosis are forbidden, including amifostine and thalidomide. The participants should avoid the concurrent use of drugs that increase the adverse reactions of pirfenidone, including ciprofloxacin, amiodarone and propafenone. The participants should also avoid concurrent administration of medications that can reduce the efficacy of pirfenidone, including omeprazole and rifampin.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint is the incidence of grade 2 or higher RILI in the full analysis set and per-protocol set. RILI will be evaluated according to CTCAE V.5.029 within 1 year. Secondary endpoints include the incidence of RILI of any grade, time to RILI occurrence, pulmonary function changes after radiotherapy, completion rate of CCRT, disease-free survival and OS.

RLIL is a diagnosis established based on clinical suspicion or radiological findings after excluding other lung pathologies such as pre-existing pathologies and pulmonary infection. It often occurs with no specific symptom, altered vital signs, laboratory profiling or imaging findings. The familiar history of radiation and recognition of RILI are of utmost importance in the context of regular follow-up. Diagnosis and grading will be confirmed after review by multidisciplinary senior physicians, including a radiation oncologist, a pulmonologist and a radiologist. Medical history, physical parameters, chest CT scans and previous radiotherapy will be evaluated at every follow-up during personal visits when available. RILI will be scored based on the CTCAE V.5.0 classifying symptoms and imaging findings will be used to classify into five grades.29 For symptoms, dyspnoea and dry cough are the most common manifestations in acute lung injury.30 Occasional fever is usually mild, but high fever is sometimes reflective of co-infectious pneumonitis. Chronic radiation fibrosis (RF) is a slowly progressing respiratory disease that can manifest as respiratory insufficiency. In terms of physical symptoms, physical examination findings may be normal or include pleural rub, moist rales and signs of consolidation. Chest imaging, particular lung CT at baseline and follow-up are critical in the diagnosis and grading. In the acute phase, which usually appears 4–8 weeks after radiotherapy, CT images may display exudative changes such as multiple small patchy or flock-shaped ground glass density shadows in the irradiation field, with fuzzy edges and unclear boundaries with surrounding lung tissue. In the consolidation phase, which usually occurs 2–3 months after radiotherapy, CT images may display patchy high-density consolidations in the irradiation field, not distributed according to the lung lobe or lung segment, accompanied by partial air bronchial signs. In the fibrotic stage, which usually occurs 6 months after radiotherapy, CT images may show density enhancement shadows of grid, cord or patchy shape in the irradiation field with clear boundaries, accompanied by thickened pleura, lung volume reduction, lung hilum reduction, ipsilateral vascular texture thinning and compensatory increase in contralateral lung volume.31–35

Considering the anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic properties of pirfenidone, the grade will be scored at the maximal level in cases who experience radiation pneumonitis (RP) and RF. When one case shows grade 3 RP and grade 2 RF, grade 3 will be recorded for the primary endpoint. As pirfenidone is a promising drug for the prevention of RP and RF, we chose 1 year to observe the rates of RP and RF.

Follow-up

During the intervention period

CBC and biochemical profiles will be verified once a week.

Physical examination and nutritional score assessment will be performed once a week.

Pulmonary function and chest/abdominal CT will be performed after 23 fractions to assess tumour regression and eligibility for surgery.

Post-treatment

The follow-up period will be 1 year or until death. All participants will be followed-up at 1 month after radiotherapy and every 3 months thereafter, or as needed clinically. Routine follow-up will include the assessment of clinical symptoms, CBC and tumour markers, contrast-enhanced CT and upper gastrointestinal contrast and pulmonary function evaluation. Repeated gastroscopy is recommended for the first year. In case of suspected recurrence, physical examination, radiography and pathological examination will be performed.

Statistical analysis

Based on retrospective studies in the authors’ hospital and literature reviews,7 8 36–38 it is assumed that the occurrence rate of grade ≥2 RILI in the control group is 25%, versus 10% in the pirfenidone group. This trial is designed as a randomised phase 2 study with a two-sided α of 0.20 and a power of 80%,39 using the PASS software V.15.0.5 to calculate the sample size. From a phase 2 screening design, a higher α level than 0.05 will be used for the next phase 3 design. Even if the phase 2 trial is successful, such a positive result is not usually considered to be definitive without a subsequent phase 3 trial. In this study, 36 participants will be included in each group with an α-level of 0.2 and a power of 80%. Considering a dropout rate of 20%, it is planned to enrol about 88 participants.

All analyses will be performed with SAS V.9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). The t-test will be used for analysing continuous data. The χ2 test and Fisher’s exact probability method will be used for comparing categorical data. The survival rate will be calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and between-group comparisons will use the log-rank test. The CI of the survival distribution will be calculated according to Greenwood’s formula. A proportional hazard regression model for risk estimation will be used to derive HRs. P value<0.05 will be considered statistically significant.

Data collection and management

All clinical data will be collected by a research assistant and recorded in detail in the predesigned electronic table. All written informed consent forms will be stored in a separate closet, and only researchers would access the relevant research data. All study procedures were developed to ensure data protection and confidentiality.

Dissemination

The results will be disseminated in international peer-reviewed conferences and journals.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public are not involved in the design or execution of the study or the outcome measures.

Discussion

For many years, radiotherapy (RT) has been employed for the treatment of oesophageal cancer as a curative or palliative measure. However, RILI is a common and severe side effect of radiation, which can delay or interrupt antitumour therapy, resulting in poor local control of the disease, decreased quality of life and even death. Therefore, prophylactic drugs to minimise toxicity and maximise efficacy in RT are required. To date, the only FDA-approved cytoprotective agent is amifostine, but limited effectiveness and significant side effects hamper its clinical application.14 15 34 35 Consequently, pharmaceutical agents that are clinically applicable, especially for the prevention of RILI are being developed40–42 Pirfenidone is a small-molecule biosynthetic drug with anti-inflammatory, antifibrotic and antioxidant properties,16–18 43 which was approved by the FDA for the management of IPF.23 24 44–46 As RILI has similar pathogenesis and clinical manifestations as IPF, characterised by inflammatory cell infiltration, interstitial oedema and interstitial fibrosis of the alveolar wall,26 pirfenidone may hold promise for the prevention and treatment of RILI, which has been tested in preclinical and pilot studies.27 47–49 Currently, a multicentre phase Ⅱ study on the treatment of RILI with pirfenidone is ongoing (NCT03902509), but no clinical study on the prevention has been reported. This is the first phase Ⅱ study designed to explore the efficacy of pirfenidone in RILI prevention.

Most published data on RILI were derived from lung cancer. However, differences in anatomy, pathogenesis and treatment between lung and oesophageal tumours limit the extrapolation of RP prediction models for pulmonary tumours to oesophageal tumours. This preliminary study was designed to focus on thoracic ESCC. Additionally, from the current National Comprehensive Cancer Network(NCCN) guidelines and expert recommendations, tolerance dose-limits for the lung vary from V20≤20% for oesophageal and oesophagogastric junction cancers, and V20≤35%–40% for non-small cell lung cancer. Obviously, oesophageal cancer has more stringent restrictions on V20, which can be achieved by oesophageal adenocarcinoma (EA) treatment plan, since it is mainly present in the lower thoracic area in European and American countries. But ESCC,50 51 highly prevalent in China and other Asian countries, is often located in the upper or middle oesophagus. Therefore, compared with EA cases in whom the RT area is close to the abdomen and the lung is relatively well protected, patients with thoracic ESCC are at higher risk of lung exposure and may require particular attention.52 Consequently, the recommended tolerance dose-limits of the lung are V20≤28–30%, V5≤60% and mean lung dose<15 Gy53 in the present study.

The estimated incidence of RILI varies widely across oesophageal cancer studies from 3.33% to 35% for grade 2 lung injury, and 0% to 21% for grade 3 lung injury. It is likely due to variations of target delineation, radiation dose, radiotherapy techniques10–12 36 54–58 and classification systems. Since consensus on the optimal radiation strategy for nodal irradiation is lacking and the accuracy of imaging diagnosis is insufficient,59 FDG-PET/CT at diagnosis is strongly recommended. Further, ENI is adopted depending on the location of the primary tumour. Although the dose of 50 Gy is the standard for CCRT in most Western countries, 60 Gy using modern radiation technologies is preferred by clinicians in Asian countries based on the belief that 50 Gy may not be enough for ESCC.53 60 61 Consequently, 60 Gy for PTV–GTV and 50.4 Gy for PTV–CTV will be administered in the present study. However, only PTV–GTV or PTV–CTV irradiation is allowed when normal tissue constraints cannot be met by therapy, which is decided by the physician. Additionally, due to the anatomical features of the oesophagus, including the lack of serosa and the presence of numerous surrounding organs, most patients in this trial have cT4N+M0 thoracic oesophageal cancer. Until now, a standard treatment option for cT4N+M0 thoracic oesophageal cancer has not been established, and therefore, definitive chemoradiotherapy (CRT) or chemoradiotherapy plus conversional surgery for downstaging are both accepted treatments.61 The major difference between neoadjuvant and definitive CRT is the radiation dose (41.4 Gy vs 50–60 Gy), which is the most crucial factor affecting the development of RILI. For this reason, stratified random cluster sampling will be applied for balancing the two groups.

Considering anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic properties,16–18 43 the incidence of grade 2 or higher RILI is the primary endpoint to test in the prevention of symptomatic RP and RF. The diagnosis of RILI is challenging due to differential or concomitant diseases such as infections and exacerbation of pre-existing pulmonary conditions. Particularly, in some cases pneumonia patches in the radiation beam pathway as well as RP complicated with infectious pneumonia could not be identified.58 In addition, RP grading is limited by subjectivity, especially in diagnosing grade 2 and grade 3. Therefore, the classification will be confirmed by a board-certified radiation oncologist referring to a joint expert consultation. The multidisciplinary team consists of a senior radiation oncologist, a pulmonologist and a radiologist with broad experience in RILI.

In summary, the present study design attempted to control for most of the important risk factors for RILI as described above. The results might provide new options for the prevention of RILI. However, owing to the limited sample size, further research is required to substantiate the efficacy of pirfenidone in the prevention of RILI using a multicentre phase 3 trial with a larger sample size.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all the patients who will participate in this trial and all participating doctors and investigators who devoted their time and passion to the implementation of this study. We are grateful to Xiaobo Li and Jianping Zhang for their contribution to the revision of the manuscript. We thank Beijing Continent Pharmaceutical for providing both the pirfenidone and placebo capsules.

Footnotes

Contributors: BX, the principal investigator responsible for the study design, also revised the article critically and approved the final version to be published. CC mainly participated in protocol design and writing. BZ and YY were responsible for statistical analysis and study design. CC and MK were responsible for surgery recommendation. DX, RC, SL and ZL made substantial contributions to the design of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The pirfenidone and placebo are provided by Beijing Continent Pharmaceuticals (no grant number). The study was funded by the Fourth Batch of Hospital Key Discipline Construction Program of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital (No. 2021FLK01KY).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:87–108. 10.3322/caac.21262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Herskovic A, Martz K, al-Sarraf M, et al. Combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy compared with radiotherapy alone in patients with cancer of the esophagus. N Engl J Med 1992;326:1593–8. 10.1056/NEJM199206113262403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper JS, Guo MD, Herskovic A, et al. Chemoradiotherapy of locally advanced esophageal cancer: long-term follow-up of a prospective randomized trial (RTOG 85-01). radiation therapy Oncology Group. JAMA 1999;281:1623–7. 10.1001/jama.281.17.1623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Minsky BD, Pajak TF, Ginsberg RJ, et al. Int 0123 (radiation therapy Oncology Group 94-05) phase III trial of combined-modality therapy for esophageal cancer: high-dose versus standard-dose radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:1167–74. 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Q-Q, Liu M-Z, Hu Y-H, et al. Definitive concomitant chemoradiotherapy with docetaxel and cisplatin in squamous esophageal carcinoma. Dis Esophagus 2010;23:253–9. 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2009.01003.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du F, Wang Q, Wang W. Analysis of related factors of radiation pneumonitis after radiotherapy for thoracic segment esophageal cancer. Zhong Hua Fang She Yi Xue Yu Fang Hu Za Zhi 2020;40:832–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao Y, Shen W, Zhu S. Low dose volume of lung in predicting acute radiation pneumonitis in patients with middle and lower thoracic esophageal cancer. Zhong Liu Fang Zhi Yan Jiu 2015:32–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhen L, Zhao S, Xu C, et al. Clinical and dosimetric factors associated with acute radiation-induced pneumonitis in esophageal carcinoma patients after intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT). Zhen Duan Xue Li Lun Yu Shi Jian 2019;0:66–71. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu W, Tan Y, Xiao N, et al. Analysis of influencing factors of radiation-induced lung injury in patients with esophageal cancer treated by IMRT. Tian Jin Yi Yao 2019:159–62. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu W-H, Wang L-H, Zhou Z-M, et al. Comparison of conformal and intensity-modulated techniques for simultaneous integrated boost radiotherapy of upper esophageal carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2004;10:1098–102. 10.3748/wjg.v10.i8.1098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, Liang S, Li C, et al. A novel nomogram and risk classification system predicting radiation pneumonitis in patients with esophageal cancer receiving radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2019;105:1074–85. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chandra A, Guerrero TM, Liu HH, et al. Feasibility of using intensity-modulated radiotherapy to improve lung sparing in treatment planning for distal esophageal cancer. Radiother Oncol 2005;77:247–53. 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen W, Xu J, Li S, et al. Prognostic analysis of intensity-modulated radiotherapy for cervical and upper thoracic esophageal carcinoma. Zhong Hua Fang She Zhong Liu Xue Za Zhi 2020;29:842–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orditura M, De Vita F, Belli A, et al. Efficacy and safety profile of amifostine in the preoperative combined therapy of esophageal cancer patients. Oncol Rep 2000;7:397–400. 10.3892/or.7.2.397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jatoi A, Martenson JA, Foster NR, et al. Paclitaxel, carboplatin, 5-fluorouracil, and radiation for locally advanced esophageal cancer: phase II results of preliminary pharmacologic and molecular efforts to mitigate toxicity and predict outcomes: North central cancer treatment group (N0044). Am J Clin Oncol 2007;30:507–13. 10.1097/COC.0b013e31805c139a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oku H, Nakazato H, Horikawa T, et al. Pirfenidone suppresses tumor necrosis factor-alpha, enhances interleukin-10 and protects mice from endotoxic shock. Eur J Pharmacol 2002;446:167–76. 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01757-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iyer SN, Gurujeyalakshmi G, Giri SN. Effects of pirfenidone on procollagen gene expression at the transcriptional level in bleomycin hamster model of lung fibrosis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1999;289:211–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Misra HP, Rabideau C. Pirfenidone inhibits NADPH-dependent microsomal lipid peroxidation and scavenges hydroxyl radicals. Mol Cell Biochem 2000;204:119–26. 10.1023/a:1007023532508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iyer SN, Gurujeyalakshmi G, Giri SN. Effects of pirfenidone on transforming growth factor-beta gene expression at the transcriptional level in bleomycin hamster model of lung fibrosis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1999;291:367–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gurujeyalakshmi G, Hollinger MA, Giri SN. Pirfenidone inhibits PDGF isoforms in bleomycin hamster model of lung fibrosis at the translational level. Am J Physiol 1999;276:L311–8. 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.2.L311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iyer SN, Wild JS, Schiedt MJ, et al. Dietary intake of pirfenidone ameliorates bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis in hamsters. J Lab Clin Med 1995;125:779–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kehrer JP, Margolin SB. Pirfenidone diminishes cyclophosphamide-induced lung fibrosis in mice. Toxicol Lett 1997;90:125–32. 10.1016/s0378-4274(96)03845-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Margaritopoulos GA, Trachalaki A, Wells AU, et al. Pirfenidone improves survival in IPF: results from a real-life study. BMC Pulm Med 2018;18:177. 10.1186/s12890-018-0736-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams TN, Eiswirth C, Newton CA, et al. Pirfenidone for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;194:374–6. 10.1164/rccm.201602-0258RR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ying H-J, Fang M, Chen M. Progress in the mechanism of radiation-induced lung injury. Chin Med J 2020;134:161–3. 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Türkkan G, Willems Y, Hendriks LEL, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: current knowledge, future perspectives and its importance in radiation oncology. Radiother Oncol 2021;155:269–77. 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qin W, Liu B, Yi M, et al. Antifibrotic agent pirfenidone protects against development of radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis in a murine model. Radiat Res 2018;190:396–403. 10.1667/RR15017.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Esophageal and esophagogastric junction cancers (version 3), 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.USDOHAH S . Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE), 2017. Available: https://ctepcancergov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_85x11pdf

- 30.Rodrigues G, Lock M, D'Souza D, et al. Prediction of radiation pneumonitis by dose - volume histogram parameters in lung cancer--a systematic review. Radiother Oncol 2004;71:127–38. 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larici AR, del Ciello A, Maggi F, et al. Lung abnormalities at multimodality imaging after radiation therapy for non-small cell lung cancer. Radiographics 2011;31:771–89. 10.1148/rg.313105096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi YW, Munden RF, Erasmus JJ, et al. Effects of radiation therapy on the lung: radiologic appearances and differential diagnosis. Radiographics 2004;24:985–97. discussion 98. 10.1148/rg.244035160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamashita H, Takahashi W, Haga A, et al. Radiation pneumonitis after stereotactic radiation therapy for lung cancer. World J Radiol 2014;6:708–15. 10.4329/wjr.v6.i9.708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Linda A, Trovo M, Bradley JD. Radiation injury of the lung after stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for lung cancer: a timeline and pattern of CT changes. Eur J Radiol 2011;79:147–54. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghaye B, Wanet M, El Hajjam M. Imaging after radiation therapy of thoracic tumors. Diagn Interv Imaging 2016;97:1037–52. 10.1016/j.diii.2016.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Asakura H, Hashimoto T, Zenda S, et al. Analysis of dose-volume histogram parameters for radiation pneumonitis after definitive concurrent chemoradiotherapy for esophageal cancer. Radiother Oncol 2010;95:240–4. 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ishida K, Ando N, Yamamoto S, et al. Phase II study of cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil with concurrent radiotherapy in advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: a Japan Esophageal Oncology Group (JEOG)/Japan Clinical Oncology Group trial (JCOG9516). Jpn J Clin Oncol 2004;34:615–9. 10.1093/jjco/hyh107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen C, Zeng B, Xue D, et al. Preliminary report of pirfenidone for the prevention of radiation pneumonitis in patients with esophageal cancer: analysis using inverse probability of treatment weighting. Chin J Clin Oncol 2021;48:772–6. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubinstein LV, Korn EL, Freidlin B, et al. Design issues of randomized phase II trials and a proposal for phase II screening trials. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:7199–206. 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ozturk B, Egehan I, Atavci S, et al. Pentoxifylline in prevention of radiation-induced lung toxicity in patients with breast and lung cancer: a double-blind randomized trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004;58:213–9. 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)01444-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ghosh SN, Zhang R, Fish BL, et al. Renin-Angiotensin system suppression mitigates experimental radiation pneumonitis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009;75:1528–36. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.07.1743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kharofa J, Cohen EP, Tomic R, et al. Decreased risk of radiation pneumonitis with incidental concurrent use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and thoracic radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;84:238–43. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakazato H, Oku H, Yamane S, et al. A novel anti-fibrotic agent pirfenidone suppresses tumor necrosis factor-alpha at the translational level. Eur J Pharmacol 2002;446:177–85. 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01758-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Troy LK, Corte TJ. Therapy for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: lessons from pooled data analyses. Eur Respir J 2016;47:27–30. 10.1183/13993003.01669-2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Noble PW, Albera C, Bradford WZ, et al. Pirfenidone for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: analysis of pooled data from three multinational phase 3 trials. Eur Respir J 2016;47:243–53. 10.1183/13993003.00026-2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.King TE, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2083–92. 10.1056/NEJMoa1402582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ji W, Jiang Y, Yang W, et al. Pirfenidone in prevention and treatment of radiation pulmonary fibrosis. Zhong Hua Fang She Zhong Liu Xue Za Zhi 2010;6:560–3. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun Y-W, Zhang Y-Y, Ke X-J, et al. Pirfenidone prevents radiation-induced intestinal fibrosis in rats by inhibiting fibroblast proliferation and differentiation and suppressing the TGF-β1/Smad/CTGF signaling pathway. Eur J Pharmacol 2018;822:199–206. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simone NL, Soule BP, Gerber L, et al. Oral pirfenidone in patients with chronic fibrosis resulting from radiotherapy: a pilot study. Radiat Oncol 2007;2:19. 10.1186/1748-717X-2-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rustgi AK, El-Serag HB. Esophageal carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2014;371:2499–509. 10.1056/NEJMra1314530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arnold M, Ferlay J, van Berge Henegouwen MI, et al. Global burden of oesophageal and gastric cancer by histology and subsite in 2018. Gut 2020;69:1564–71. 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stiles BM, Altorki NK. The NeoRes trial: Questioning the benefit of radiation therapy as part of neoadjuvant therapy for esophageal adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Dis 2017;9:3465–8. 10.21037/jtd.2017.08.146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.National Health Commission Of The People's Republic Of China . Chinese guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of esophageal carcinoma 2018 (English version). Chin J Cancer Res 2019;31:223–58. 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2019.02.01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ishikura S, Nihei K, Ohtsu A, et al. Long-Term toxicity after definitive chemoradiotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:2697–702. 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suntharalingam M, Winter K, Ilson D, et al. Effect of the addition of cetuximab to paclitaxel, cisplatin, and radiation therapy for patients with esophageal cancer: the NRG oncology RTOG 0436 phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:1520–8. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.1598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shi Z, Foley KG, Pablo de Mey J, et al. External validation of radiation-induced dyspnea models on esophageal cancer radiotherapy patients. Front Oncol 2019;9:1411. 10.3389/fonc.2019.01411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tonison JJ, Fischer SG, Viehrig M, et al. Radiation pneumonitis after intensity-modulated radiotherapy for esophageal cancer: institutional data and a systematic review. Sci Rep 2019;9:2255. 10.1038/s41598-018-38414-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hsieh H-Y, Yeh H-L, Hsu C-P, et al. Feasibility of intensity-modulated radiotherapy for esophageal cancer in definite chemoradiotherapy. J Chin Med Assoc 2016;79:375–81. 10.1016/j.jcma.2016.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Akiyama H, Tsurumaru M, Udagawa H, et al. Radical lymph node dissection for cancer of the thoracic esophagus. Ann Surg 1994;220:364–72. discussion 72-3. 10.1097/00000658-199409000-00012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang W, Luo Y, Wang X, et al. Dose-Escalated radiotherapy improved survival for esophageal cancer patients with a clinical complete response after standard-dose radiotherapy with concurrent chemotherapy. Cancer Manag Res 2018;10:2675–82. 10.2147/CMAR.S160909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kuwano H, Nishimura Y, Oyama T, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of carcinoma of the esophagus April 2012 edited by the Japan esophageal Society. Esophagus 2015;12:1–30. 10.1007/s10388-014-0465-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.