Abstract

Objective

To identify strategies and interventions used to improve interprofessional collaboration and integration (IPCI) in primary care.

Design

Scoping review

Data sources

Specific Medical Subject Headings terms were used, and a search strategy was developed for PubMed and afterwards adapted to Medline, Eric and Web of Science.

Study selection

In the first stage of the selection, two researchers screened the article abstracts to select eligible papers. When decisions conflicted, three other researchers joined the decision-making process. The same strategy was used with full-text screening. Articles were included if they: (1) were in English, (2) described an intervention to improve IPCI in primary care involving at least two different healthcare disciplines, (3) originated from a high-income country, (4) were peer-reviewed and (5) were published between 2001 and 2020.

Data extraction and synthesis

From each paper, eligible data were extracted, and the selected papers were analysed inductively. Studying the main focus of the papers, researchers searched for common patterns in answering the research question and exposing research gaps. The identified themes were discussed and adjusted until a consensus was reached among all authors.

Results

The literature search yielded a total of 1816 papers. After removing duplicates, screening titles and abstracts, and performing full-text readings, 34 papers were incorporated in this scoping review. The identified strategies and interventions were inductively categorised under five main themes: (1) Acceptance and team readiness towards collaboration, (2) acting as a team and not as an individual; (3) communication strategies and shared decision making, (4) coordination in primary care and (5) integration of caregivers and their skills and competences.

Conclusions

We identified a mix of strategies and interventions that can function as ‘building blocks’, for the development of a generic intervention to improve collaboration in different types of primary care settings and organisations.

Keywords: PRIMARY CARE, Organisation of health services, PUBLIC HEALTH, Protocols & guidelines, Quality in health care

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

The review focuses exclusively on primary care; thus, our findings are not directly transferable to other healthcare levels.

Only articles written in English were included. Therefore, we may have missed valuable literature.

Only studies performed in high-income countries were included in this review; hence, our findings are not directly transferable to other countries because differences in health systems, financing, governance, title protection and culture can pose significant implementation challenges.

The risk of bias to the interpretation of the data was minimised by triangulating researchers from different backgrounds (eg, nurses, pharmacists and a psychologist) throughout the whole review process and conducting the selection of articles with a team of at least two researchers.

We did not limit the search to the collaboration between specific types of caregivers, or in relation to a specific disease, or condition of patients. Therefore, our data and analysis can be used in the context of or added to a broad scope of interprofessional collaboration and integration in primary care.

Introduction

As the world population is ageing, the growing complexity of healthcare and health needs, together with the associated financial challenges1 and the fragmentation of primary care,2–4 are prompting a fundamental rethink of how primary care should be organised and how professionals in different settings should collaborate.5 As approximately one-third of the world population lives with a chronic disease,6 and as primary care is usually the first point of access to the care system, integrated care at that level in which professionals closely collaborate, both interdisciplinary and interprofessional, is unquestionably important in current and future care organisations.

Interprofessional collaboration can be beneficial to achieving a more integrated primary healthcare and should overcome the aforementioned challenges and problems. According to the WHO, interprofessional collaboration occurs when two or more professions work together to achieve common goals.7 Orchard et al8 defined it as involving a partnership between a team of health professionals and a client in a participatory, collaborative and coordinated approach to shared decision-making around health and social issues. As Goodwin et al9 and Lewis et al10 saw an efficient interprofessional collaboration as a prerequisite for integrated care. Edmondson et al11 indicated that psychological safety, defined as a shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking, is a critical factor in understanding teamwork and organisational learning.

Next to health professionals, informal caregivers are involved in interprofessional collaboration.12 According to the WHO,13 informal caregivers should be considered full partners in care and they mostly consist of families and friends of the patient. To measure the collaboration and coordination of these formal and informal caregivers, many questionnaires are available.14 The Assessment of Interprofessional Team Collaboration Scale is an example consisting of the subscales; partnership, cooperation and coordination, and can be deployed in primary healthcare.15

To achieve and maintain interprofessional collaboration in primary care, Bardet et al16 identified the following key elements: trust, interdependence, perceptions and expectations from the other healthcare professionals, their skills, their interest for collaborative practice, their role definition and their communication.17–23 These key elements are also present in the five dimensions of integrated care that Valentijn et al24 25 described in the Rainbow model as follows: system, organisational, professional, clinical, functional and normative integration. Integrated care and quality collaboration between professionals leads to improved access to care,26 better health outcomes27 and enhanced prevention.28 29

Although several literature reviews identified strategies to influence, improve or facilitate interprofessional collaboration, a thorough analysis of the interventions is lacking. Most review papers focused on the collaboration of a single type of caregiver or one specific disease.27 30–38 Therefore, it is difficult to broaden these findings to primary care and chronic conditions in general.

To fill this gap, we performed a scoping review to identify strategies and interventions improving and/or facilitating interprofessional collaboration and integration (IPCI) in primary care. More specifically, we listed and analysed the existing strategies, interventions and their outcomes, without focusing on a specific profession or disease. Based on the definitions of interprofessional collaboration7 8 and integrated care,9 10 24 25 we included papers, thus outlining strategies and interventions working on microlevel, mesolevel and macrolevel. The included papers described organisational, relational and processual factors influenced by these interventions and strategies.

This review was conducted as the first phase of a research project to develop an evidence-based toolkit, guiding health professionals in their transition towards IPCI of different competencies, skills and roles as well as the role of patients and their needs in primary care.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review using the Arksey and O’Malley framework39: (1) identifying the research questions, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) selecting studies, (4) charting the data and (5) collating, summarising and reporting results. We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines and the PRISMA-ScR templates to help conduct the scoping review.40

Step 1: identifying the research questions

An exploratory literature search was performed preliminarily to identifying the research question on IPCI in primary care. Based on this literature search, we developed the following research question: Which strategies and/or interventions improve or facilitate IPCI in primary care? We aimed to search for articles containing generic strategies and methods used in primary care settings, to facilitate IPCI in primary care. Five researchers were involved in identifying this research question for the scoping review.

Step 2: identifying relevant studies: search strategy

We used specific Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and free text terms to design a search strategy around the following key concepts: primary care, healthcare team, integration and interprofessional collaboration. We combined the keywords and MeSH terms presented in box 1 with the Boolean terms ‘OR’, ‘AND’ and ‘NOT’. The search strategy was developed for PubMed and afterwards adapted to Medline, Eric and Web of Science and was performed between March and June 2020. The full search strategy is available in online supplemental material.

Box 1. keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms used to identify relevant data.

MeSh/search terms and combinations for PubMed

primary care

primary healthcare

primary health care

1 or 2t or 3 (Title/abstract)

integrative team

integrative teams

collaborative practice

collaborative practices

interdisciplinary team

interdisciplinary teams

multidisciplinary team

multidisciplinary teams

interprofessional team

interprofessional teams

healthcare team

healthcare teams

health care team

health care teams

5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 (title/abstract)

interprofessional collaboration

interprofessional teamwork

interprofessional team work

interdisciplinary collaboration

interdisciplinary teamwork

interdisciplinary team work

multidisciplinary collaboration

20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 (All fields)

4 AND 19 AND 27

bmjopen-2022-062111supp001.pdf (82.8KB, pdf)

Step 3: study selection

Articles were included if they: (1) were in English, (2) described an intervention to improve interprofessional collaboration or integration in primary care involving at least two different healthcare disciplines, (3) originated from a high-income country,41 (4) were peer-reviewed and (5) were published between 2001 and 2020. Articles were excluded when: (1) the research methods and findings were not thoroughly described, (2) it concerned opinion papers, (3) the study focused on a single disease or group of patients/clients and (4) when the full text was not available.

We used Rayyan42 to collect and organise eligible articles. In the first stage of the selection, MMS and PvB screened the article abstracts to select eligible papers, according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and to eliminate the duplicates. When decisions conflicted, three other researchers (HDL, KDV and KVdB) joined the decision-making process; they were blind to the decisions of the first two reviewers, and each screened a third of the conflicting abstracts. In the second stage of the selection, the initial two reviewers read the full texts of the selected articles. As in the first stage, studies were included or excluded depending on the agreement of both reviewers. When the decisions of the two reviewers conflicted, the other researchers joined the decision-making process and a procedure similar to the one outlined above was followed.

Charting the data

From each paper, eligible data were extracted using a self-developed descriptive template. The following characteristics were recorded: a full reference citation (author, title, journal and publication date); the methodology used to conduct the research; a summary of the intervention or strategy used to facilitate IPCI and the impact on IPCI.

Step 5: collating, summarising and reporting the data

The selected papers were analysed inductively. Studying the main focus of the papers, we searched for common patterns among them, answering the research question and/or exposing research gaps. We, thus, identified themes and subthemes, which were discussed and adjusted until consensus was reached among all authors. Subsequently, all selected papers were coded using the defined themes. Using a tabular overview and summary of the selected literature, the iterative analysis and discussion among the authors were facilitated and allowed the extraction of the interventions and strategies of interest.

Patient and public involvement

This scoping review did not directly involve patients or public.

Results

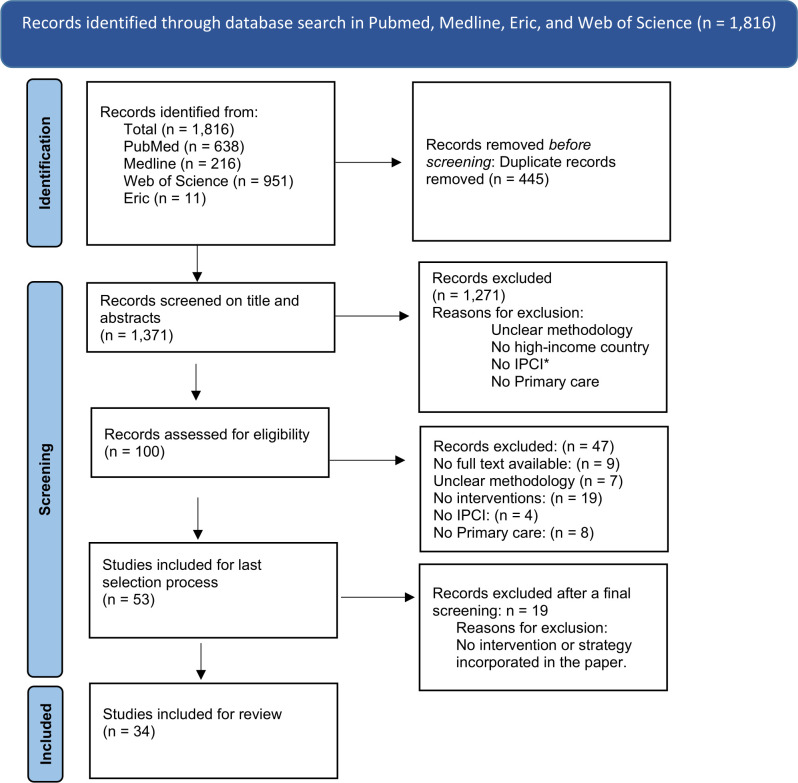

The literature search yielded a total of 1816 papers, of which 445 duplicates were removed (figure 1). On screening titles and abstracts of the remaining 1371 records, only 100 were eligible given the inclusions criteria outlined above. After further reading, 47 studies, lacking an intervention, were excluded. Finally, 19 more articles were excluded because they did not include strategies or interventions. This resulted in 34 papers describing strategies and interventions to facilitate IPCI in primary care. A Flow diagram on the selection procedure is available in figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. *IPCI, interprofessional collaboration or integration. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Findings

Five main themes, essential for IPCI, emerged from our analyses: (1) Acceptance and team readiness towards collaboration (n=21), (2) acting as a team and not as an individual (n=26); (3) communication strategies and shared decision making (n=16), (4) coordination in primary care (n=20) and (5) integration of caregivers and their skills and competences (n=16). An overview of the interventions is presented in table 1, while an overview of the articles sorted in themes is presented in table 2.

Table 1.

An overview of the characteristics of the selected articles

| Author and year | Title | Journal | Country | Study design | Intervention/strategy |

| Bentley et al 201766 | Interprofessional teamwork in comprehensive primary healthcare services: findings from a mixed methods study | Journal of interprofessional care | Australia | Mixed methods study. Online survey, and interviews with managers and practitioners | Introduction of a comprehensive primary healthcare method |

| Berkowitz et al. 201665 | Case study: Johns Hopkins community health partnership: a model for transformation | The journal of delivery science and innovation | USA | Case study | The Johns Hopkins Community Health Partnership. A community-based intervention. using multidisciplinary care. |

| Chan et al. 201043 | Finding common ground? Evaluating an intervention to improve teamwork among primary healthcare professionals | International journal of quality in healthcare | Australia | Mixed methods study: Qualitative interviews, observations and a survey assessing multidisciplinary teamwork were used. | A 6 month intervention (The Team-link intervention) consisting of an educational workshop and structured facilitation using specially designed materials, backed up by informal telephone support. |

| Coleman et al. 200844 | Interprofessional ambulatory primary care practice-based educational programme | Journal of interprofessional care | USA | A longitudinal cohort study with a quantitative evaluation. | STAR-project: an educational programme for teams of nurse practitioners, family medicine residents and social work students to work together at clinical sites in the delivery of longitudinal care in primary care ambulatory clinics. |

| Curran et al. 200745 | Evaluation of an interprofessional continuing professional development initiative in primary healthcare | Journal of continuing education in the health professions | Canada | Mixed methods study: An evaluation research design, prestudy to poststudy with quantitative and qualitative instruments. | Introducing The Building a Better Tomorrow Initiative, which is a continuing professional development programme. |

| Goldman et al. 201046 | Interprofessional primary care protocols: a strategy to promote an evidence-based approach to teamwork and the delivery of care | Journal of interprofessional care | Canada | Qualitative study. | Implementation of an interprofessional protocol |

| Grace et al. 201447 | Flexible implementation and integration of new team members to support patient-centred care | The journal of delivery science and innovation | USA | Mixed methods: Interviews and a survey with primary care professionals. | Introduction of interprofessional primary care protocols |

| Hilts et al. 201348 | Helping primary care teams emerge through a quality improvement programme | Oxford academic: family practice | Canada | A qualitative exploratory case study approach. | Introducing a quality improvement programme. |

| Josi et al. 202067 | Advanced practice nurses in primary care in Switzerland: an analysis of interprofessional collaboration | BMC nursing | Switzer- land | Qualitative study with an ethnographic design. | Integration of an advanced practice nurse in a primary care team. |

| Kim et al. 201949 | What makes team communication effective: a qualitative analysis of interprofessional primary care team members’ perspectives | Journal of interprofessional care | USA | Qualitative study. Grounded theory method of constant comparison. | Standardised communication tools used with the implementation of the patient-centred medical home |

| Kotecha et al. 201568 | Influence of a quality improvement learning collaborative programme on team functioning in primary healthcare | Journal of collaborative family healthcare | Canada | A qualitative study using a phenomenological approach was conducted as part of a mixed-method evaluation. | Quality Improvement Learning Collaborative Programme to support the development of interdisciplinary team function, and improve chronic disease management, disease prevention and access to care. |

| Légaré et al. 202050 | Validating a conceptual model for an inter-professional approach to shared decision making: a mixed methods study | Journal of evaluation in clinical practice | Canada | Qualitative study. Thematic analysis of the transcripts and a descriptive analysis of the questionnaires were performed. | An interprofessional shared decision-making model. |

| Lockhart et al. 201969 | Engaging primary care physicians in care coordination for patients with complex medical conditions | Canadian family physician | Canada | Qualitative study. Care professionals were interviewed 14 to 19 months after the initiation of an intervention. | Initiation of the Seamless Care Optimising the Patient Experience project. |

| MacNaughton et al. 201370 | Role construction and boundaries in interprofessional primary healthcare teams: a qualitative study | BMC health service research | Canada | A qualitative, comparative case study with observations was conducted. | Introduction of a model to explore how roles are constructed within interprofessional healthcare teams. It focuses on elucidating the different types of role boundaries, the influences on role construction and the implications for professionals and patients. |

| Mahmood-Yousuf et al.51 2008 | Interprofessional relationships and communication in primary palliative care: impact of the gold standards framework | The British journal of general practice | UK | Qualitative interview case study. | Adoption of an interprofessional collaboration framework to investigate the extent to which the framework influences interprofessional relationships and communication, and to compare general practitioners’ and nurses’ experiences. |

| Morgan et al. 201552 | Observation of interprofessional collaborative practice in primary care teams: an integrative literature review | International journal of nursing studies | New Zealand | Integrative literature review | Several strategies to improve interprofessional collaboration in primary care teams |

| Morgan et al. 202076 | Collaborative care in primary care: the influence of practice interior architecture on informal face-to-face communication—an observational study | Health environments research & design journal | New Zealand | Qualitative study with observations | Changing the architecture of primary care settings to explore the influence of primary care practice interior architecture on face-to-face on-the-fly communication for collaborative care. |

| Murphy et al53 2017 | Change in mental health collaborative care attitudes and practice in Australia impact of participation in MHPN network meetings |

Journal of integrated care | Australia | Quantitative study: an online survey. | Introduction of the Mental Health Professionals Network. Investigating attitudinal and practice changes among health professionals after participation in MHPN’s (Mental Health Professionals Network) network meetings. |

| Pullon et al. 201671 | Observation of interprofessional collaboration in primary care practice: a multiple case study | Journal of interprofessional care | New- Zealand | Qualitative study, using a case study design with observations. | Identifying existing strategies to maintain and improve interprofessional collaboration in primary care practices. |

| Reay et al. 201354 | Legitimising new practices in primary healthcare | Healthcare management review | Canada | A qualitative, longitudinal comparative case study. | Developing effective interdisciplinary teams in primary healthcare. |

| Reeves et al. 201775 | Interprofessional collaboration to improve professional practice and healthcare outcomes | Cochrane review | Canada | Systematic review | Nine interventions were analysed. |

| Robben et al. 201272 | Impact of interprofessional education on collaboration attitudes, skills, and behaviour among primary care professionals | Journal of continuing education in the health professions | Netherlands | Mixed methods study: Before-after study, using the Interprofessional Attitudes Questionnaire, Attitudes Toward Healthcare Teams Scale, and Team Skills Scale. Additionally, semi-structured interviews were conducted | Introduction of an interprofessional education programme with interdisciplinary workshops. |

| Rodríguez et al. 201077 | The implementation evaluation of primary care groups of practice: a focus on organisational identity | BMC family practice | Canada | Qualitative study. An in-depth longitudinal case study was conducted over two and a half years. | Implementation of primary care groups of practice, with a focus on the emergence of the organisational identity. |

| Rodriguez et al. 201555 | Availability of primary care team members can improve teamwork and readiness for change | Healthcare management review | USA | Quantitative study with a survey, using path analysis. | A four-stage developmental interprofessional collaborative relationship-building model: To assess primary care team structure (team size, team member availability, and access to interdisciplinary expertise), teamwork, and readiness for change. |

| Russell et al. 201856 | Contextual levers for team-based primary care: lessons from reform interventions in five jurisdictions in three countries | Health service research | Canada | An international consortium of researchers met via teleconference and regular face-to-face meetings using a Collaborative Reflexive Deliberative Approach to reanalyse and synthesise their published and unpublished data and their own work experience. | Determining existing strategies and methods to improve interprofessional collaboration and integration in primary care. |

| Sargeant et al. 200857 | Effective interprofessional teams: ‘ontact is not enough’ to build a team | Journal of continuing education in the health professions | Canada | Qualitative, grounded theory study. | Introducing an interprofessional educational programme. |

| Tierney et al. 201958 | Interdisciplinary team working in the Irish primary healthcare system: analysis of ‘invisible’ bottom-up innovations using normalisation process theory | Journal of health policy | Ireland | Mixed methods study: An online survey and an interview study. | Bottom-up innovations using Normalisation Process Theory: (1)Design and delivery of educational events. in the community for preventive care and health promotion. (2)Development of integrated care plans for people with complex health needs. (3) Advocacy on behalf of patients. |

| Valaitis et al. 202073 | Examining interprofessional teams structures and processes in the implementation of a primary care intervention (health tapestry) for older adults using normalisation process theory | BMC family practice | Canada | Qualitative study. Applying the NPT and a descriptive qualitative approach embedded in a mixed-methods, pragmatic RCT. | Strengthening Quality (Health TAPESTRY) is a primary care intervention aimed at supporting older adults that involves trained volunteers, interprofessional teams, technology and system navigation. |

| van Dongen et al. 2018a59 | Suitability of a programme for improving interprofessional primary care team meetings | International journal of integrated care | Netherlands | Mixed methods study: a process evaluation using a mixed-methods approach including both qualitative and quantitative data. | Introducing a multifaceted programme including a reflection framework, training activities and a toolbox. |

| van Dongen et al. 201660 | Interprofessional collaboration regarding patients’ care plans in primary care: a focus group study into influential factors | BMC family practice | Netherlands | Qualitative study with an inductive content analysis. | Improving interprofessional collaboration by using patients’ care plans. |

| van Dongen et al. 2018b74 | Development of a customisable programme for improving interprofessional team meetings: an action research approach | International journal of integrated care | Netherlands | Qualitative study with an action research approach. | A Customisable Programme for Improving Interprofessional Team Meetings |

| Wener 201661 | Collaborating in the context of co-location: a grounded theory study | BMC family practice | Canada | A qualitative research paradigm where the exploration is grounded in the providers’ experiences. | A four-stage developmental interprofessional collaborative relationship-building model to guide healthcare providers and leaders as they integrate mental health services into primary care settings. |

| Wilcock et al. 200262 | The Dorset Seedcorn project: interprofessional learning and continuous quality improvement in primary care | British journal of general practice | United Kingdom | Mixed methods study. Participants kept reflective journals. The evaluation was undertaken using a mix of questionnaires and staff interviews. | The Dorset Seedcorn Project: interprofessional learning and continuous quality improvement in primary care. Implementing the principles and methods of continuous quality improvement. |

| Young et al. 201763 | Shared care requires a shared vision: communities of clinical practice in a primary care setting | BMC health service research | New Zealand | Qualitative study with observations. A focused ethnography of nine ‘Communities of Clinical Practice. | Introducing the ‘Community of Clinical Practice’ model. Forming a vision of care which is shared by patients and the primary care professionals involved in their care. |

Table 2.

Articles sorted in themes (X=paper included under that theme)

| Articles | Acceptance and team readiness towards collaboration | Acting as a team and not as an individual | Communication strategies and shared decision making | Coordination in primary care | Integration of caregivers and their skills and competences |

| Bentley et al66 | X | X | X | ||

| Berkowitz et al65 | X | ||||

| Chan et al43 | X | X | X | ||

| Coleman et al44 | X | X | X | ||

| Curran et al45 | X | X | X | X | X |

| Goldman et al46 | X | X | X | X | |

| Grace et al47 | X | X | X | X | |

| Hilts et al48 | X | X | X | ||

| Josi et al67 | X | X | X | ||

| Kim et al49 | X | X | X | ||

| Kotecha et al68 | X | X | X | ||

| Légaré et al50 | X | X | X | X | |

| Lockhart et al69 | X | X | |||

| MacNaughton et al70 | X | X | X | ||

| Mahmood-Yousuf et al51 | X | X | X | ||

| Morgan 201552 | X | X | X | ||

| Morgan 202076 | X | ||||

| Murphy et al53 | X | X | X | ||

| Pullon et al71 | X | X | |||

| Reay et al54 | X | X | X | ||

| Reeves et al75 | X | X | |||

| Robben et al72 | X | ||||

| Rodríguez 2010.77 | X | ||||

| Rodriquez 201555 | X | X | X | ||

| Russell et al56 | X | X | X | ||

| Sargeant et al57 | X | X | X | X | |

| Tierney et al58 | X | x | X | X | |

| Valaitis et al73 | X | X | X | ||

| van Dongen 2018a59 | X | X | X | X | X |

| van Dongen 2018b60 | X | X | X | X | |

| van Dongen 201674 | X | ||||

| Wener and Woodgate61 | X | X | X | X | |

| Wilcock et al62 | X | X | |||

| Young et al63 | X | X | X | ||

| # Articles | 21 | 26 | 16 | 20 | 16 |

Theme 1: acceptance and team readiness towards collaboration

Twenty-one articles provided strategies to improve the acceptance and team readiness towards collaboration.43–63 Before being able to collaborate, caregivers need to accept working as a team. Team readiness towards collaboration occurs when team members obtain the right mindset to take necessary measures for efficient collaboration. This does not mean that an efficient collaboration has been reached, but both acceptance and team readiness were a prerequisite to achieving it. Acceptance and team readiness of caregivers towards collaboration were strongly influenced by their attitude, awareness, knowledge and understanding, and caregiver satisfaction.

Interventions on changing caregivers’ attitudes towards collaboration seem to facilitate teamwork.64 Workshops and information sessions were organised to make changes in caregivers’ attitudes, in which advantages of teamwork and finding common ground were explained and lectured.44 50 55 56 59–61 63 Basic knowledge about the potential of teamwork was learnt by using logical explanations.44 50 55 56 59–61 63 65 Caregivers to whom the advantages of collaboration were explained were more likely to accept and adopt the principles of interprofessional collaboration. Simple and accessible knowledge transfer seems to be an important characteristic of a successful intervention on the attitude and knowledge of caregivers.43 51 57 59 60

Some articles44 46 49 53 59 63 reported on strategies to increase awareness about collaboration in primary care. Increased awareness resulted in a better acceptance and team readiness towards collaboration. Making caregivers aware of their shortcomings and the need for collaboration with different disciplines seemed an effective way to facilitate interprofessional collaboration. In addition to awareness, potential improvements in care quality,44 47 62 caused by better collaboration, motivate caregivers to change their attitude. Furthermore, some studies45 48 52 54 58 61 62 reported that increased caregiver satisfaction was considered as a facilitator of collaboration between caregivers.

Theme 2: acting as a team and not as an individual

Twenty-six articles provided strategies to act as a team and not as an individual.43 45–48 50 52 54–63 66–74 In some articles,54 55 57 61 62 this was mentioned as collaborative behaviour, which was considered to be a facilitator of teamwork. Moreover, showing mutual respect and trust50 55 59–63 68 70 between caregivers were important facilitators towards collaboration: it improves acting as a team, and it supports a safe team climate. An environment of greater psychological safety improved collaborative behaviour, and in some cases, it replaced working in silos with working as a team.45 48 62 69 71 74

Developing and enhancing a shared vision, shared values and shared goals were mentioned as facilitators towards interprofessional collaboration.43 47 50 61 63 66 This was achieved by a structural inclusion of every team member in the development of the teams’ vision, values and goals.63 By simply writing down these principles, caregivers were more likely to participate in developing shared principles.43 47 Although the development process was not explained in detail, three articles mentioned that once developed, shared vision, goals and values were crucial to maintaining a beneficial collaboration.50 61 63 To establish these shared principles, a patient-centred focus may be an important asset. By prioritising the patient’s needs and preferences, caregivers can find common ground more easily.58–60 63 67 73

Leadership seems of utmost importance to act as a team. Strategies towards collaborative leadership and shared leadership were mentioned in the articles,46 56 59 66–68 70 72 74 and leaders and decision makers should be aware of the potential effects of policy and structural changes on interprofessional teamwork. By using a clear role assignment, caregivers can prevent issues in their collaboration.52 59 61 63 However, in one case,48 a rotational leadership was implemented and suggested, in which there was no permanent leader.

One paper emphasised that awareness of potential unintended negative effects of changes on the functioning of interprofessional teams should be taken into account by decision makers.67

Theme 3: communication strategies and shared decision-making

Sixteen articles provided communication strategies and strategies to facilitate shared decision-making, to improve interprofessional collaboration in primary care.44–47 49–52 58–60 63 66–68 75 These strategies can be further delineated into the following subthemes: (1) knowledge about each other,47 58 59 (2) formal and informal meetings,45 52 59 60 66 67 75 (3) the use of structured guidelines and protocols,46 47 58 60 (4) conflict resolution44 51 59 60 63 67 and (5) relational equality.49 50 63 68

Knowing each other’s professional roles and tasks seems a precondition for teamwork. However, knowing more about each other’s family situation, interests and hobbies was also mentioned to be important to improve the communication and collaboration between caregivers.47 58 59

Both formal45 59 60 67 75 and informal52 60 66 team meetings, mainly happening between caregivers working in the same practice (under one roof),52 were considered as an important communication strategy. Formal meetings were mostly used to share information about patients or clients, distribute tasks and identify and solve problems in the organisation. Planning and structuring a team meeting can increase the efficiency and productivity of these meetings.45 59 60 67 75 Informal meetings were important to know more about each other and facilitated the trust relations between caregivers. Information that could not be shared in the formal meetings often appeared in the informal meetings. Even lunches with team members were used as a communication strategy.52 60 66

Structured guidelines, standardised tools and protocols were used to improve the communication and coordination between caregivers working in primary care. These protocols provided more effective communication and the provision of an evidence-based approach towards collaboration and care delivery. Besides using protocols, workshops were organised to improve communication.46 47 58 60

Making decisions as a team was an indicator of good and effective communication. Shared decision-making was mentioned in nine studies,44 49–51 59 60 63 67 68 and our analysis identified conflict resolution44 51 59 60 63 67 and relational equality49 50 63 68 as key factors to improve shared decision-making.

Theme 4: coordination in primary care

By collaborating with different disciplines and professions, many caregivers were experiencing problems regarding information sharing43 49 54 57 59 61 65 68 71 73 and referring44 45 49 51 55 59 61 65 66 68 between primary healthcare workers. Twenty articles, therefore, provided strategies to improve coordination in order to ameliorate information sharing between caregivers, to facilitate referrals for the patient and to guarantee the continuity of care.43–45 49 51 53–55 59 61 65 66 68–73 75 76 Accordingly, reciprocity and reciprocal interdependence were shown to play a crucial role in the coordination of primary care.55 61

Colocation and the importance of architecture and building characteristics were, in some cases, mentioned as influential factors for collaboration.70 75 76 By optimising the architecture and working under one roof, brief face-to-face interactions may increase. The architecture could be optimised by having shared spaces, thus leading to increased staff proximity or visibility. Especially informal communication was positively affected by the presence of convenient circulatory (eg, foyers and lobbies) and transitional (eg, courtyards, verandas and corridors) spaces.70 75 76 Additionally, weekly or monthly face-to-face meetings were organised to coordinate care. Face-to-face meetings and electronic task queues facilitate information sharing and efficient care coordination for complex patients.75 76

Theme 5: integration of caregivers and their skills and competences

Fifteen papers provided strategies to improve the integration of caregivers and their skills and competences in primary care practices45–48 50 53 56–61 67 70 73 77 and tried to get the most out of every team member’s presence.

For new team members, a successful integration was facilitated by welcoming the newcomers and making them know and understand the vision of the practice. Inclusion of the caregiver required additional proactive efforts regarding communication and coordination among practice members.47 61 In some cases, a personal, one-to-one meeting with the new team member could facilitate problem-solving.47

Eleven papers presented an improved integration of caregivers skills and competences, as a facilitator for task distribution and role clarification.45 46 48 50 56 59–61 67 70 73 Knowing each other’s capabilities, including skills and competences, was very important in this regard.46 48 61 70 In addition, making sure that caregivers not only know each other’s skills and competences but also enable more transparency about their daily needs and preferences were mentioned as facilitators.48 56 59 61 70 Six articles presented strategies to optimise the use of team members’ skills and competences. By acknowledging and affirming their capabilities, integration of skills and competences was facilitated.50 53 58 59 61 77

In one article, researchers indicated that the organisation of team communication-training workshops and implementation of flexible protocols gave practice stakeholders significant discretion to integrate new care team roles to best fit local needs. Furthermore, it improved team communication and functioning because of increased engagement and local leadership facilitation.47

Discussion

This scoping review identified five themes for interventions and strategies aimed at improving and facilitating IPCI in primary care. The first category, which incorporates acceptance and team readiness, was a precondition for enhancing and maintaining efficient interprofessional collaboration. Accepting to collaborate requires a change of attitude, which involves valuing team members and actively soliciting the opinions or receiving feedback from other team members.78 A major barrier to adopting a suitable attitude towards collaboration is the difficulty and complexity of sharing responsibility for patient care within a team.79 80 Making caregivers aware of their shortcomings and the need for collaboration with different disciplines are effective ways to facilitate interprofessional collaboration.44 46 49 53 59 63 In addition, Liedvogel et al.81 demonstrated that experiencing teamwork itself increases the awareness of the advantages, and the importance of collaboration, as well as gives caregivers opportunities to demonstrate their skills and capabilities. In the broader community, increased awareness of the importance of interprofessional collaboration can lead to an improved experience and understanding of the totality of healthcare services.81 Furthermore, according to Lockwood and Maguire,82 it can also help to reduce the sense of isolation experienced by solo medical practitioners.

Second, collaborative behaviour has been described as a facilitator of teamwork.54 55 57 61 62 To enhance and maintain a collaborative behaviour, the development of shared principles (such as shared vision, values and goals) is an important prerequisite.43 47 50 61 63 66 Our review revealed that maintaining a safe team climate in which care professionals feel comfortable is important to act as a team and not as an individual.45 48 62 69 71 74 Although psychological safety is not often mentioned in primary care research,22 Edmondson11 and Kim et al83 had indicated the essential role of a safe workplace environment in enhancing teamwork. Team psychological safety is defined as a shared value; the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking.84 This means that team members feel they will not be punished or humiliated for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns or mistakes. A team may not be able to collaborate properly if there is a lack of psychological safety; hence, it is assumed that psychological safety is a necessary but insufficient condition for increasing interprofessional collaboration and workplace effectiveness.85

Third, structured guidelines and protocols seem to be beneficial for communication between care professionals, thereby impacting IPCI. Team meetings, especially formal meetings, can be held more efficiently by using protocols, that have positive effects on hierarchy and conflicts resolution between team members.86 Although interventions in our review did not give attention to informal meetings as much as existing literature,87–89 Burm et al87 indicated that, by recognising the importance of informal meetings, care providers are more motivated to organise or participate in informal meetings. These meetings tended to be ad hoc and improvised, and in some cases discussion topics were recorded in notebooks.88 89 The shared decision-making model has been put forward as a guide for discussing and making decisions in the most effective way.90 This model includes three principles: recognising and acknowledging that a decision is required, knowing and understanding the best available evidence, and incorporating the patient’s values and preferences into the decision.91

Fourth, as an element of IPCI, care coordination is of utmost importance for patient safety. The situation-background-assessment-recommendation protocol is an existing method to perform information sharing efficiently and appropriately.92 In addition, Lo et al93 suggested that the protocol may be a cost-effective method for coordinating between general practitioners and nurses.93 To solve problems regarding care coordination, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of digital healthcare tools was established.94 Fagherazzi et al95 indicated that these digital tools improved triage and risk assessment.

Finally, optimal integration of caregivers skills and competences has been associated with maximalising every team member’s presence and shortening the adaptation process of new team members.96 Family caregivers provide a significant portion of health and support services to individuals with serious illnesses; however, existing literature and healthcare systems have often overlooked them and mostly focused on integrating care professionals.97 98 Friedman and Tong97 suggested using a framework, in which the family caregiver is an indispensable partner of care professionals and patients.

Although all interventions or strategies are useful to a certain point, none is suitable to be used in isolation as a unique solution for IPCI in primary care. However, a mix of the interventions and strategies compiled in this scoping review may be capable of doing so. The consistency, design and order of this mix of interventions and strategies cannot be specified based on the results of this scoping review.

This scoping review has several limitations. The review focuses exclusively on primary care; thus, our findings are not directly transferable to other healthcare levels. Only studies performed in high-income countries were included in this review; hence, our findings are not directly transferable to other countries because differences in health systems, financing, governance, title protection and culture can pose significant implementation challenges. In addition, by including only English-language articles and avoiding the grey literature, we might have missed some relevant papers. It is worthwhile to note, that this scoping review aimed to identify interventions that can improve IPCI in primary care and to list their impact on outcomes related to collaboration and integration. Our review did not report the effectiveness of interventions regarding health outcomes. Contrary to generic interventions focusing on IPCI, interventions focusing on a single disease and improving health outcomes were implemented more successfully and were evaluated in a more sophisticated way, using validated scales.27 99–101

We selected articles based on WHO’s7 and Orchard’s8 definition of interprofessional collaboration. For integrated care, we adopted the definitions of Lewis et al’s10 and Valentijn et al’s25 definitions, which represent a widely accepted consensus. However, there are many other definitions of IPCI care that, if adopted, could affect the inclusion or exclusion of articles.

The literature has established that researchers can influence the interpretation of data. This risk of bias was minimised by triangulating researchers from different backgrounds (eg, nurses, pharmacists and a psychologist) through the whole process and conducting the selection of articles with a team of at least two researchers. This triangulation, intensive cooperation and inductive process increased the credibility and reduced the risk of bias to the interpretation of the data based on preconceived understanding and personal opinions.

A strength of this review is the fact that we did not limit the search to the collaboration between specific types of caregivers, or in relation to a specific disease, or condition of patients. Therefore, our data and analysis can be used in the context of or added to a broad scope of IPCI in primary care. Furthermore, we performed an inductive analysis within a multidisciplinary team of researchers, to expand the analysis and to identify generic strategies and interventions.

Conclusion

This scoping review identified five categories of strategies and interventions to improve or facilitate IPCI in primary care: (1) acceptance and team readiness towards collaboration, (2) acting as a team and not as an individual, (3) communication strategies and shared decision making, (4) coordination in primary care and (5) integration of caregivers and their skills and competences. We did not identify a single strategy or intervention which is broad or generic enough to be used in every type of primary care setting.

We can conclude that a mix of the identified strategies and interventions, which we illustrated as ‘building blocks’, can provide valuable input to develop a generic intervention to be used in different settings and levels of primary healthcare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the partnership with the Primary Care Academy (www.academie-eerstelijn.be) and want to thank the King Baudouin Foundation and Fund Daniel De Coninck for the opportunity they offer us for conducting research and have impact on the primary care of Flanders, Belgium. The consortium of the Primary Care Academy consists Lead author: Roy Remmen–roy.remmen@uantwerpen.be—Department of Primary Care and Interdisciplinary Care, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences. University of Antwerp. Antwerp. Belgium; Emily Verté—Department of Primary Care and Interdisciplinary Care, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences. University of Antwerp. Antwerp. Belgium, Department of Family Medicine and Chronic Care, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy. Vrije Universiteit Brussel. Brussel. Belgium; Muhammed Mustafa Sirimsi—Centre for research and innovation in care, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences. University of Antwerp. Antwerp. Belgium; Peter Van Bogaert—Workforce Management and Outcomes Research in Care, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences. University of Antwerp. Belgium; Hans De Loof—Laboratory of Physio pharmacology, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Biomedical and Veterinary Sciences. University of Antwerp. Belgium; Kris Van den Broeck—Department of Primary Care and Interdisciplinary Care, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences. University of Antwerp. Antwerp. Belgium.; Sibyl Anthierens—Department of Primary Care and Interdisciplinary Care, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences. University of Antwerp. Antwerp. Belgium; Ine Huybrechts—Department of Primary Care and Interdisciplinary Care, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences. University of Antwerp. Antwerp. Belgium.; Peter Raeymaeckers—Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Faculty of Social Sciences. University of Antwerp. Belgium; Veerle Buffel- Department of Sociology; centre for population, family and health, Faculty of Social Sciences. University of Antwerp. Belgium.; Dirk Devroey- Department of Family Medicine and Chronic Care, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy. Vrije Universiteit Brussel. Brussel.; Bert Aertgeerts—Academic Centre for General Practice, Faculty of Medicine. KU Leuven. Leuven, Department of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine, KU Leuven. Leuven; Birgitte Schoenmakers—Department of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine, KU Leuven. Leuven. Belgium; Lotte Timmermans—Department of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine, KU Leuven. Leuven. Belgium.; Veerle Foulon—Department of Pharmaceutical and Pharmacological Sciences, Faculty Pharmaceutical Sciences. KU Leuven. Leuven. Belgium.; Anja Declerq—LUCAS-Centre for Care Research and Consultancy, Faculty of Social Sciences. KU Leuven. Leuven. Belgium.; Nick Verhaeghe—Research Group Social and Economic Policy and Social Inclusion, Research Institute for Work and Society. KU Leuven. Belgium.; Dominique Van de Velde Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, Occupational Therapy. Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences. University of Ghent. Belgium., Department of Occupational Therapy. Artevelde University of Applied Sciences. Ghent. Belgium.; Pauline Boeckxstaens—Department of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine and Health sciences. University of Ghent. Belgium.; An De Sutter -Department of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine and Health sciences. University of Ghent. Belgium.; Patricia De Vriendt—Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, Occupational Therapy. Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences. University of Ghent. Belgium., Frailty in Ageing (FRIA) Research Group, Department of Gerontology and Mental Health and Wellbeing (MENT) research group, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy. Vrije Universiteit. Brussels. Belgium., Department of Occupational Therapy. Artevelde University of Applied Sciences. Ghent. Belgium.; Lies Lahousse—Department of Bioanalysis, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Ghent University. Ghent. Belgium.; Peter Pype—Department of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine and Health sciences. University of Ghent. Belgium., End-of-Life Care Research Group, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences. Vrije Universiteit Brussel and Ghent University. Ghent. Belgium.; Dagje Boeykens- Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, Occupational Therapy. Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences. University of Ghent. Belgium., Department of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine and Health sciences. University of Ghent. Belgium.; Ann Van Hecke—Department of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine and Health sciences. University of Ghent. Belgium., University Centre of Nursing and Midwifery, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences. University of Ghent. Belgium.; Peter Decat—Department of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine and Health sciences. University of Ghent. Belgium.; Rudi Roose—Department of Social Work and Social Pedagogy, Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences. University Ghent. Belgium.; Sandra Martin—Expertise Centre Health Innovation. University College Leuven-Limburg. Leuven. Belgium.; Erica Rutten—Expertise Centre Health Innovation. University College Leuven-Limburg. Leuven. Belgium.; Sam Pless—Expertise Centre Health Innovation. University College Leuven-Limburg. Leuven. Belgium.; Vanessa Gauwe—Department of Occupational Therapy. Artevelde University of Applied Sciences. Ghent. Belgium.; Didier Reynaert- E-QUAL, University College of Applied Sciences Ghent. Ghent. Belgium.; Leen Van Landschoot—Department of Nursing, University of Applied Sciences Ghent. Ghent. Belgium.; Maja Lopez Hartmann—Department of Welfare and Health, Karel de Grote University of Applied Sciences and Arts. Antwerp. Belgium.; Tony Claeys- LiveLab, VIVES University of Applied Sciences. Kortrijk. Belgium.; Hilde Vandenhoudt—LiCalab, Thomas University of Applied Sciences. Turnhout. Belgium.; Kristel De Vliegher—Department of Nursing–homecare, White-Yellow Cross. Brussels. Belgium.; Susanne Op de Beeck—Flemish Patient Platform. Heverlee. Belgium. Kristel driessens—Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social Sciences. University of Antwerp. Belgium

Footnotes

Contributors: All listed authors meet authorship criteria and no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. The following role distribution was given to perform the scoping review: (1) development of the research question and establishment of the search strategy: MMS, HDL, KdV, KVdB and PvB, (2) database search: MMS and PvB, (3) record screening: MMS, PvB, HDL, KDV and KVdB performed abstract and full text screenings, (4) data analysis: MMS, HDL, KdV, KVdB and PvB, (5) discussion construction: MMS, HDL, KdV, KVdB, PP, RR and PVB, (6) writing-review and editing: MMS, HDL, KdV, KVdB, PP, RR and PvB. Finally, MMS is the guarantor of this scoping review.

Funding: This research was funded by fund Daniël De Coninck, King Baudouin Foundation, Belgium. The funder had no involvement in this study. Grant number: 2019-J5170820-211588.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Holman HR. The relation of the chronic disease epidemic to the health care crisis. ACR Open Rheumatol 2020;2:167–73. 10.1002/acr2.11114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Misra V, Sedig K, Dixon DR, et al. Prioritizing coordination of primary health care. Can Fam Physician 2020;66:399–403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lublóy Ágnes, Keresztúri JL, Benedek G. Lower fragmentation of coordination in primary care is associated with lower prescribing drug costs-lessons from chronic illness care in Hungary. Eur J Public Health 2017;27:826–9. 10.1093/eurpub/ckx096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Timmins L, Kern L, Ghosh A, et al. Predicting fragmented care: beneficiary, primary care physician, and practice characteristics. Health Serv Res 2021;56:60–1. 10.1111/1475-6773.13782 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frandsen BR, Joynt KE, Rebitzer JB, et al. Care fragmentation, quality, and costs among chronically ill patients. Am J Manag Care 2015;21:355-62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van der Heyden J, Gezondheidsenquête RC. Chronische ziekten en aandoeningen. 2018. Belgium: Sciensano, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization, . Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. World Health Organization, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orchard CA. Persistent isolationist or collaborator? the nurse's role in interprofessional collaborative practice. J Nurs Manag 2010;18: :248–57. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01072.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodwin, Nick, et al. Integrated care for patients and populations: improving outcomes by working together. London: King’s Fund, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis Richard Q., et al. Where next for integrated care organisations in the English NHS. London: The Nuffield Trust, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edmondson AC. The fearless organization: creating psychological safety in the workplace for learning, innovation, and growth. John Wiley & Sons, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boeykens D, Sirimsi MM, Timmermans L, et al. How do people living with chronic conditions and their informal caregivers experience primary care? A phenomenological-hermeneutical study. J Clin Nurs 2022. 10.1111/jocn.16243. [Epub ahead of print: 17 Feb 2022]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health O. WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services: interim report. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bookey-Bassett S, Markle-Reid M, McKey C, et al. A review of instruments to measure interprofessional collaboration for chronic disease management for community-living older adults. J Interprof Care 2016;30: :201–10. 10.3109/13561820.2015.1123233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orchard C, Pederson LL, Read E, et al. Assessment of interprofessional team collaboration scale (AITCS): further testing and instrument revision. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2018;38:11–18. 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bardet J-D, Vo T-H, Bedouch P, et al. Physicians and community pharmacists collaboration in primary care: a review of specific models. Res Social Adm Pharm 2015;11:602–22. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2014.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaudhri K, Hayek A, Liu H, et al. General practitioner and pharmacist collaboration: does this improve risk factors for cardiovascular disease and diabetes? A systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2019;9:e027634. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graham F, Tang MY, Jackson K, et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementation of shared medical appointments in primary care for the management of long-term conditions: a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ Open 2021;11:e046842. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rathbone AP, Mansoor SM, Krass I, et al. Qualitative study to conceptualise a model of interprofessional collaboration between pharmacists and general practitioners to support patients' adherence to medication. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010488. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reeves S, Fletcher S, McLoughlin C, et al. Interprofessional online learning for primary healthcare: findings from a scoping review. BMJ Open 2017;7:e016872. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmutz JB, Meier LL, Manser T. How effective is teamwork really? the relationship between teamwork and performance in healthcare teams: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2019;9:e028280. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sholl S, Scheffler G, Monrouxe LV, et al. Understanding the healthcare workplace learning culture through safety and dignity narratives: a UK qualitative study of multiple stakeholders' perspectives. BMJ Open 2019;9:e025615. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Dongen JJJ, Lenzen SA, van Bokhoven MA, et al. Interprofessional collaboration regarding patients’ care plans in primary care: a focus group study into influential factors. BMC Fam Pract 2016;17:1–10. 10.1186/s12875-016-0456-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodwin N. Understanding integrated care: a complex process, a fundamental principle. Int J Integr Care 2013;13:e011. 10.5334/ijic.1144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valentijn PP, Boesveld IC, van der Klauw DM, et al. Towards a taxonomy for integrated care: a mixed-methods study. Int J Integr Care 2015;15:e003. 10.5334/ijic.1513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaur L, Tadros E. The benefits of interprofessional collaboration for a pharmacist and family therapist. Am J Fam Ther 2018;46:470–85. 10.1080/01926187.2018.1563003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reeves S, Pelone F, Harrison R, et al. Interprofessional collaboration to improve professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;6:CD000072. 10.1002/14651858.CD000072.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roller-Wirnsberger R, Lindner S, Liew A, et al. European collaborative and interprofessional capability framework for prevention and management of Frailty-a consensus process supported by the joint action for frailty prevention (advantage) and the European geriatric medicine Society (EuGMS). Aging Clin Exp Res 2020;32:561–70. 10.1007/s40520-019-01455-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bachynsky N. Implications for policy: The triple aim, quadruple aim, and interprofessional collaboration. in Nursing Forum. Wiley Online Library, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zwarenstein M, Goldman J, Reeves S. Interprofessional collaboration: effects of practice‐based interventions on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2009;3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reeves S, Goldman J, Gilbert J, et al. A scoping review to improve conceptual clarity of interprofessional interventions. J Interprof Care 2011;25:167–74. 10.3109/13561820.2010.529960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johansen JS, Havnes K, Halvorsen KH, et al. Interdisciplinary collaboration across secondary and primary care to improve medication safety in the elderly (IMMENSE study): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020106. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoare E, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Skouteris H, et al. Systematic review of mental health and well-being outcomes following community-based obesity prevention interventions among adolescents. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006586. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.House S, Havens D. Nurses' and physicians' perceptions of Nurse-Physician collaboration: a systematic review. J Nurs Adm 2017;47:165–71. 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Körner M, Bütof S, Müller C, et al. Interprofessional teamwork and team interventions in chronic care: a systematic review. J Interprof Care 2016;30:15–28. 10.3109/13561820.2015.1051616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell AR, Layne D, Scott E, et al. Interventions to promote teamwork, delegation and communication among registered nurses and nursing assistants: an integrative review. J Nurs Manag 2020;28:1465–72. 10.1111/jonm.13083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buljac-Samardzic M, Doekhie KD, van Wijngaarden JDH. Interventions to improve team effectiveness within health care: a systematic review of the past decade. Hum Resour Health 2020;18:2. 10.1186/s12960-019-0411-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johansson G, Eklund K, Gosman-Hedström G. Multidisciplinary team, working with elderly persons living in the community: a systematic literature review. Scand J Occup Ther 2010;17:101–16. 10.3109/11038120902978096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.WorldBank . World bank country and lending groups, 2021. Available: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups

- 42.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan-a web and mobile APP for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016;5:210. 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chan BC, Perkins D, Wan Q, et al. Finding common ground? evaluating an intervention to improve teamwork among primary health-care professionals. Int J Qual Health Care 2010;22:519–24. 10.1093/intqhc/mzq057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coleman MT, Roberts K, Wulff D, et al. Interprofessional ambulatory primary care practice-based educational program. J Interprof Care 2008;22:69–84. 10.1080/13561820701714763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Curran V, Sargeant J, Hollett A. Evaluation of an interprofessional continuing professional development initiative in primary health care. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2007;27:241–52. 10.1002/chp.144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goldman J, Meuser J, Lawrie L, et al. Interprofessional primary care protocols: a strategy to promote an evidence-based approach to teamwork and the delivery of care. J Interprof Care 2010;24:653–65. 10.3109/13561820903550697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grace SM, Rich J, Chin W, et al. Flexible implementation and integration of new team members to support patient-centered care. Health Care 2014;2:145–51. 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2014.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hilts L, Howard M, Price D, et al. Helping primary care teams emerge through a quality improvement program. Fam Pract 2013;30:204–11. 10.1093/fampra/cms056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim LY, Giannitrapani KF, Huynh AK, et al. What makes team communication effective: a qualitative analysis of interprofessional primary care team members' perspectives. J Interprof Care 2019;33:836–8. 10.1080/13561820.2019.1577809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Légaré F, Stacey D, Gagnon S, et al. Validating a conceptual model for an inter-professional approach to shared decision making: a mixed methods study. J Eval Clin Pract 2011;17:554–64. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01515.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mahmood-Yousuf K, Munday D, King N, et al. Interprofessional relationships and communication in primary palliative care: impact of the gold standards framework. Br J Gen Pract 2008;58:256–63. 10.3399/bjgp08X279760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morgan S, Pullon S, McKinlay E. Observation of interprofessional collaborative practice in primary care teams: an integrative literature review. Int J Nurs Stud 2015;52:1217–30. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Murphy B, Gibbs C, Hoppe K, et al. Change in mental health collaborative care attitudes and practice in Australia impact of participation in MHPN network meetings. Journal of Integrated Care 2018;26:29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reay T, Goodrick E, Casebeer A, et al. Legitimizing new practices in primary health care. Health Care Manage Rev 2013;38:9–19. 10.1097/HMR.0b013e31824501b6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rodriguez HP, Chen X, Martinez AE, et al. Availability of primary care team members can improve teamwork and readiness for change. Health Care Manage Rev 2016;41:286–95. 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Russell GM, Miller WL, Gunn JM, et al. Contextual levers for team-based primary care: lessons from reform interventions in five jurisdictions in three countries. Fam Pract 2018;35:276–84. 10.1093/fampra/cmx095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sargeant J, Loney E, Murphy G. Effective interprofessional teams: "contact is not enough" to build a team. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2008;28:228–34. 10.1002/chp.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tierney E, Hannigan A, Kinneen L, et al. Interdisciplinary team working in the Irish primary healthcare system: Analysis of 'invisible' bottom up innovations using Normalisation Process Theory. Health Policy 2019;123:1083–92. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van Dongen JJJ, van Bokhoven MA, Goossens WNM, et al. Suitability of a programme for improving interprofessional primary care team meetings. Int J Integr Care 2018;18:12. 10.5334/ijic.4179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Dongen JJJ, van Bokhoven MA, Goossens WNM, et al. Development of a Customizable programme for improving interprofessional team meetings: an action research approach. Int J Integr Care 2018;18:8. 10.5334/ijic.3076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wener P, Woodgate RL. Collaborating in the context of co-location: a grounded theory study. BMC Fam Pract 2016;17:30. 10.1186/s12875-016-0427-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wilcock PM, Campion-Smith C, Head M. The Dorset Seedcorn project: interprofessional learning and continuous quality improvement in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2002;52 Suppl:S39–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Young J, Egan T, Jaye C, et al. Shared care requires a shared vision: communities of clinical practice in a primary care setting. J Clin Nurs 2017;26:2689–702. 10.1111/jocn.13762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zheng RM, Sim YF, Koh GC-H. Attitudes towards interprofessional collaboration among primary care physicians and nurses in Singapore. J Interprof Care 2016;30:505–11. 10.3109/13561820.2016.1160039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Berkowitz SA, Brown P, Brotman DJ, et al. Case study: Johns Hopkins community health partnership: a model for transformation. Health Care 2016;4:264–70. 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2016.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bentley M, Freeman T, Baum F, et al. Interprofessional teamwork in comprehensive primary healthcare services: findings from a mixed methods study. J Interprof Care 2018;32:274–83. 10.1080/13561820.2017.1401986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Josi R, Bianchi M, Brandt SK. Advanced practice nurses in primary care in Switzerland: an analysis of interprofessional collaboration. BMC Nurs 2020;19:1. 10.1186/s12912-019-0393-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kotecha J, Brown JB, Han H, et al. Influence of a quality improvement learning collaborative program on team functioning in primary healthcare. Fam Syst Health 2015;33:222–30. 10.1037/fsh0000107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lockhart E, Hawker GA, Ivers NM, et al. Engaging primary care physicians in care coordination for patients with complex medical conditions. Can Fam Physician 2019;65:E155–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.MacNaughton K, Chreim S, Bourgeault IL. Role construction and boundaries in interprofessional primary health care teams: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:486. 10.1186/1472-6963-13-486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pullon S, Morgan S, Macdonald L, et al. Observation of interprofessional collaboration in primary care practice: a multiple case study. J Interprof Care 2016;30:787–94. 10.1080/13561820.2016.1220929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Robben S, Perry M, van Nieuwenhuijzen L, et al. Impact of interprofessional education on collaboration attitudes, skills, and behavior among primary care professionals. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2012;32:196–204. 10.1002/chp.21145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Valaitis R, Cleghorn L, Dolovich L, et al. Examining interprofessional teams structures and processes in the implementation of a primary care intervention (health TAPESTRY) for older adults using normalization process theory. BMC Fam Pract 2020;21:14. 10.1186/s12875-020-01131-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.van Dongen JJJ, Lenzen SA, van Bokhoven MA, et al. Interprofessional collaboration regarding patients' care plans in primary care: a focus group study into influential factors. BMC Fam Pract 2016;17:58. 10.1186/s12875-016-0456-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Reeves S, Pelone F, Harrison R. Interprofessional collaboration to improve professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;6:Cd000072. 10.1002/14651858.CD000072.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Morgan S, Pullon S, McKinlay E, et al. Collaborative care in primary care: the influence of practice interior architecture on informal face-to-face Communication—An observational study. HERD 2021;14:190–209. 10.1177/1937586720939665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rodríguez C, Pozzebon M. The implementation evaluation of primary care groups of practice: a focus on organizational identity. BMC Fam Pract 2010;11:15. 10.1186/1471-2296-11-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lavelle M, Reedy GB, Cross S, et al. An evidence based framework for the temporal observational analysis of teamwork in healthcare settings. Appl Ergon 2020;82:102915. 10.1016/j.apergo.2019.102915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Anderson JE, Lavelle M, Reedy G. Understanding adaptive teamwork in health care: progress and future directions. J Health Serv Res Policy 2021;26:135581962097843:208–14. 10.1177/1355819620978436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Braithwaite J, Clay-Williams R, Vecellio E, et al. The basis of clinical tribalism, hierarchy and stereotyping: a laboratory-controlled teamwork experiment. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012467. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liedvogel M, Haesler E, Anderson K. Who will be running your practice in 10 years? -- supporting GP registrars' awareness and knowledge of practice ownership. Aust Fam Physician 2013;42:333–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lockwood A, Maguire F. General practitioners and nurses collaborating in general practice. Aust J Prim Health 2000;6:19–29. 10.1071/PY00015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kim S, Lee H, Connerton TP. How psychological safety affects team performance: mediating role of efficacy and learning behavior. Front Psychol 2020;11:1581. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Edmondson A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm Sci Q 1999;44:350–83. 10.2307/2666999 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Frazier ML, Fainshmidt S, Klinger RL, et al. Psychological safety: a meta-analytic review and extension. Pers Psychol 2017;70:113–65. 10.1111/peps.12183 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vardaman JM, Cornell P, Gondo MB, et al. Beyond communication: the role of standardized protocols in a changing health care environment. Health Care Manage Rev 2012;37:88–97. 10.1097/HMR.0b013e31821fa503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Burm S, Boese K, Faden L, et al. Recognising the importance of informal communication events in improving collaborative care. BMJ Qual Saf 2019;28:289–95. 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fox S, Gaboury I, Chiocchio F, et al. Communication and interprofessional collaboration in primary care: from ideal to reality in practice. Health Commun 2021;36:125–35. 10.1080/10410236.2019.1666499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Persson SS, Blomqvist K, Lindström PN. Meetings are an important prerequisite for Flourishing workplace relationships. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:8092. 10.3390/ijerph18158092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bomhof-Roordink H, Fischer MJ, van Duijn-Bakker N, et al. Shared decision making in oncology: a model based on patients', health care professionals', and researchers' views. Psychooncology 2019;28:139–46. 10.1002/pon.4923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:1361–7. 10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Müller M, Jürgens J, Redaèlli M, et al. Impact of the communication and patient hand-off tool SBAR on patient safety: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2018;8:e022202. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lo L, Rotteau L, Shojania K. Can SBAR be implemented with high fidelity and does it improve communication between healthcare workers? A systematic review. BMJ Open 2021;11:e055247. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Solomon DH, Rudin RS. Digital health technologies: opportunities and challenges in rheumatology. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2020;16:525–35. 10.1038/s41584-020-0461-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fagherazzi G, Goetzinger C, Rashid MA, et al. Digital health strategies to fight COVID-19 worldwide: challenges, recommendations, and a call for papers. J Med Internet Res 2020;22:e19284. 10.2196/19284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]