Abstract

Background: Retransitions in youth are critical to understand, as they are an experience about which little is known and about which families and clinicians worry.

Aims: This study aims to qualitatively describe the experiences of youth who made binary social transitions (came to live as the binary gender different from the one assigned at birth) in childhood by the age of 12, and who later socially transitioned genders again (here, called “retransitioning”).

Methods: Out of 317 participants in an ongoing longitudinal study of (initially) binary transgender youth, 23 participants had retransitioned at least once and were therefore eligible for this study. Of those youth, 8 were cisgender at the time of data collection, 11 were nonbinary, and 4 were binary transgender youth (after having retransitioned to nonbinary identities for a period). Fifteen youth and/or their parent(s) participated in semi-structured interviews (MYouthAge = 11.3 years; 9 non-Hispanic White; 3 Hispanic White; 3 Multiracial; 10 assigned male; 5 assigned female). Interviews gauged antecedents of transitions, others’ reactions to transitions, and participants’ general reflections. Responses were coded and thematically analyzed.

Results: Participants described various paths to retransitions, including that some youth identified differently over time, and that some youth learned about a new identity (e.g., nonbinary) that fit them better. Social environments’ responses to retransitions varied but were often neutral or positive. No participants spontaneously expressed regret over initial transitions.

Conclusions: These findings largely do not support common concerns about retransitions. In supportive environments, gender diverse youth can retransition without experiencing rejection, distress, and regret.

Keywords: Transgender youth, childhood social transition, retransition, gender development

Transgender children are children who identify as a gender other than the one assigned to them at birth. While there have been documented cases of transgender children socially transitioning—changing hairstyles, clothing, name, and/or pronouns to live in line with their gender identities—for nearly a century in the United States (Gill-Peterson, 2018), the scientific record indicates that the number of children who socially transition has likely increased considerably over the last two decades (Steensma & Cohen-Kettenis, 2011). Some authors have expressed concern around childhood social transitions, noting that some children who socially transition may later wish to transition genders again (here, called “retransitioning”), which may be distressing to them because of possible adverse reactions from people in their social environments (de Vries & Cohen-Kettenis, 2012; Green, 2017; Steensma & Cohen-Kettenis, 2011). Notably, the most recent draft of the World Professional Association of Transgender Health’s Standards of Care (Version 8) also cites this as a potential concern around childhood social transitions (SOC8 Homepage - WPATH World Professional Association for Transgender Health, n.d.). Though the hypothetical outcomes of retransitions have been much discussed, few data exist on youths’ actual experiences of retransitions. The present study aims to address this gap by describing the experiences of youth who initially made binary social transitions in childhood (i.e., lived as transgender boys or girls), and later retransitioned (to live as cisgender or nonbinary youth) at some point during their participation in an ongoing, longitudinal study of gender-diverse youth in North America.

In support of the argument that retransitions may be distressing, authors have often cited a qualitative study by Steensma et al. (2011) in which two assigned-female adolescents, who presented as masculine for a period of time, felt hesitant when they later wanted to adopt more feminine gender presentations, due to possible judgment and mistreatment from peers (Coleman et al., 2012; de Vries & Cohen-Kettenis, 2012; Green, 2017; Steensma & Cohen-Kettenis, 2011). One of the youths struggled with this for two years before deciding to present as more feminine again and, when she finally did so, experienced the teasing she had feared. Importantly, scholars have pointed out that the two youth in this study seem never to have fully socially transitioned to begin with (i.e., they wore masculine clothing and hairstyles, but did not change their pronouns or gender labels), thus their stories are limited in the degree to which they can be applied to conversations around childhood social transitions (Ashley, 2019a; Olson, 2016; Olson & Durwood, 2016). Steensma et al. (2011) does, however, exemplify how social environments can be hard on people who change their gender expressions more than once, and this may apply to youth who retransition.

In contrast with authors who express concern about retransitions (and, in turn, childhood social transitions in general), other authors have argued that retransitions can be a normal part of gender development (Ashley, 2019b; Hidalgo et al., 2013; Leibowitz, 2018). Given that some people experience their genders as being fluid (Ashley, 2019b; Temple Newhook et al., 2018), some youth may transition more than once simply because they identify differently at different times. Moreover, as Ashley (2019b) pointed out, transitions can, in themselves, be a form of exploring one’s gender, rather than being an endpoint after exploration is complete. In line with this thinking, many clinicians encourage families to stay open to the possibility that a child’s first social transition may not be their final one, and to discuss the possibility of retransitions proactively (Hidalgo et al., 2013; Leibowitz, 2018; Menvielle, 2012). One study found that most parents of socially transitioned children do explicitly discuss retransitioning as an option with their children (Olson et al., 2019).

The present authors know of only two articles that describe socially transitioned children who subsequently retransitioned. One article mentions two cases in which assigned-male children socially transitioned to live as girls, and then retransitioned to live as boys (Menvielle, 2012), but that report does not provide details about how the youth experienced these later transitions. In another review, by Edwards-Leeper and Spack (2012), the authors described their clinical impressions of a youth seen in their clinic who was assigned female at birth, socially transitioned to live as a boy, later began puberty blockers, and then discontinued puberty blockers and retransitioned to live as a girl.

“…this patient did not identify any indicators of psychological distress as a result of this decision, and, in fact, both she and her mother reported that it was only due to the freedom to experience living as a male and the availability of the puberty blocking medical intervention that she was able to make an informed decision regarding her gender identity.” (Edwards-Leeper & Spack, 2012, p. 332)

The degree to which this one case is representative or anomalous is unknown. In short, we have very little information about the experiences of youth who retransition.

Current study

In the present study, we sought to address outstanding questions about the experiences of the subset of youth who retransition. We conducted semi-structured interviews with youth and their parents (henceforth, participants) who made binary social transitions in childhood (by age 12) and later retransitioned at least once during their continued participation in our longitudinal study. These interviews gathered information about: (1) What led up to each social transition, (2) How people in the youth’s social environment reacted to each social transition, and (3) How the participant reflected on the process in general (e.g., what would they do again, or do differently if they could?). We analyzed participants’ responses using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) and summarize those themes here.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from a large, longitudinal study of 317 initially binary, socially transitioned transgender children from the US and Canada. To be included in the broader longitudinal study, youth needed to use the binary gendered pronouns other than the ones assigned to them at birth (e.g., a child assigned male at birth who used she/her pronouns, or a child assigned female at birth who used he/him pronouns; none used nonbinary pronouns at the start of the study) and be between the ages of 3–12 at the time that they first participated. The recruitment phase of the larger study ran from July 2013 to December 2017. Data collection from this cohort is ongoing. Participating families were recruited through various avenues including support groups, conferences, and camps for gender-diverse youth, as well as through clinicians, word-of-mouth, and through media stories. Given that social transitions at/before the age of 12 require (at least some) parental support, the broader study is made up of youth who are generally highly supported in their gender identities and expressions by their custodial parents (Durwood et al., 2021).

The present study focuses on the subset of (initially) binary transgender youth in the longitudinal study who retransitioned at some point before January 1st, 2021. We use the term “retransition” to describe cases in which youth participants, all of whom used binary pronouns when they began the study, later changed pronouns again—to the pronouns assigned to them at birth, to they/them pronouns, or to a mix of pronouns. We used pronoun changes as criteria for retransition because pronoun changes were the original criteria for inclusion in the longitudinal study to indicate a social transition, and in order to describe a consistent point in time for all participants (social transitions can include a number of changes that unfold over time, including changes in hairstyle, clothing, pronouns and gender label; Kuper et al., 2019). When summarizing information about groups of youth, we will use the term “cisgender” to describe youth who currently use the pronouns assigned to them at birth, “nonbinary” to describe youth who use they/them pronouns (exclusively, or a mix of pronouns including they/them), and “binary transgender” to describe youth who use the pronouns “opposite” their assigned sex at birth (e.g., see Table 2).

Table 2.

Trajectories of retransitioning youth.

| Youth | Interview participation status | Assigned sex at birth | Age at 1st social transition | Age at retransition | Age at second retransition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cisgender Youth: currently using the binary pronouns assigned to them at birth | |||||

| Youth 1 | Participated (past round of interviews) | Male | 3 to she/her | 5 to he/him | n/a |

| Youth 2 | Participated | Female | 4 to he/him | 8 to she/her | n/a |

| Youth 3 | Participated | Male | 4 to she/her | 9 to he/him | n/a |

| Youth 4 | Participated | Male | 6 to she/her | 11 to he/him | n/a |

| Youth 5 | Participated | Male | 5 to she/her | 6 to he/him | n/a |

| Youth 6 | Did not participate | Male | 4 to she/her | 8 to they/them | 9 to he/him |

| Youth 7 | Did not participate | Male | 4 to she/her | 5 to he/him | n/a |

| Youth 8 | Did not participate | Male | 5 to she/her | 5 to he/him | n/a |

| Mean age: | 4.4 | 7.1 | 9.0 | ||

| Nonbinary Youth: currently using they/them pronouns, or a mix of pronouns including they/them | |||||

| Youth 9 | Participated | Male | 3 to she/her | 8 to they/them | n/a |

| Youth 10 | Participated | Male | 5 to she/her | 10 to they/them | n/a |

| Youth 11 | Participated | Male | 5 to she/her | 9 to they/them | n/a |

| Youth 12 | Participated | Male | 6 to she/her | 9 to they/them | n/a |

| Youth 13 | Participated | Female | 7 to he/him | 11 to she/her | 12 to they/them |

| Youth 14 | Participated | Male | 7 to she/her | 10 to they/them | n/a |

| Youth 15 | Participated | Female | 10 to he/him | 13 to he/him and they/them | 14 to she/her and they/them |

| Youth 16 | Participated | Female | 10 to he/him | 12 to they/them | n/a |

| Youth 17 | Did not participate | Male | 5 to she/her | 6 to she/her and they/them | n/a |

| Youth 18 | Did not participate | Male | 5 to she/her | 7 to he/him, she/her, and they/them | n/a |

| Youth 19 | Did not participate | Female | 8 to he/him | 9 to mostly they/them or name | n/a |

| Mean age: | 6.5 | 9.5 | 13.0 | ||

| Binary Transgender Youth: currently using the binary pronouns other than the ones assigned at birth | |||||

| Youth 20 | Participated | Female | 7 to he/him | 8 to they/them and he/him | 10 to he/him |

| Youth 21 | Participated | Male | 7 to she/her | 10 to they/them | 11 to she/her |

| Youth 22 | Did not participate | Female | 11 to he/him | 13 to they/them | 14 to he/him |

| Youth 23 | Did not participate | Female | 9 to he/him | 13 to they/them | 14 to he/him |

| Mean age: | 8.5 | 11.0 | 12.3 | ||

In rare cases, these terms (“cisgender,” “nonbinary,” “binary transgender,” and “transitions” referring to pronoun changes) are imperfect representations of participants’ experiences. For example, one parent stated that she does not view her child’s adoption of they/them pronouns to be a transition, one youth who uses they/them pronouns did not use the term “nonbinary” to describe themself (they simply did not mention any gender label, and their parent implied the youth might be deciding on which term they prefer), and another parent referred to her child as having detransitioned but also as being gender nonconforming. Because of cases like this, we made sure that when we refer to youth individually (i.e., when describing them while introducing a quote), we refer to them in ways that are consistent with participants’ own descriptions. We ensured this by reading over interviews in detail, and when necessary, cross-referencing participant’s responses in other surveys in our longitudinal study, in email exchanges, etc.

Of the participants in the broader, longitudinal study, most youth (294 of the 317 participants, or 92.7%) had not retransitioned (see also Olson et al., 2022). Of the 23 youth who did retransition at least once, 8 youth (2.5%) were cisgender at the time of this analysis, 11 youth (3.5%) were nonbinary, and 4 youth (1.3%) were binary transgender youth after having lived as nonbinary for a period.1 We found that youth in the longitudinal study who had initially socially transitioned before age 6 tended to be more likely than those who transitioned at age 6 or later to retransition to their gender assigned at birth, but retransitions were rare regardless of age of initial transition (for more on this, see Olson et al., 2022).

Of the 23 retransitioned youth (and their families), 21 were invited to participate in the present interviews. The two who were not invited were one who had previously dropped out of the study, and another who had not been in touch with the research team in approximately five years. The family who had previously dropped out of the study had participated in a past round of parent phone interviews, in which the parent spontaneously described that their child had retransitioned. That parent’s responses in the previous interview provided sufficient data to be coded for the present study, and thus were included in the thematic analysis. We also include some limited information in the discussion about the known outcomes of the youth in the other family.

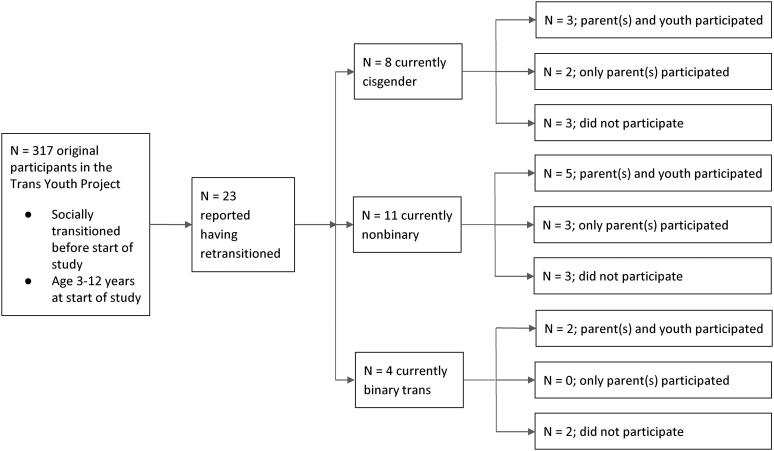

Families of retransitioning youth were contacted to participate in interviews on a rolling basis; both the youth and their parent(s) were invited to participate in one-on-one interviews about the youth’s retransition experience. Of the 21 families invited, 14 families had at least one family member participate. In some families, the child and two parents participated (n = 6), in others the child and one parent participated (n = 4), and in others just one parent participated (n = 4). Combined with the parent who participated in a past phone interview, in which just one parent participated, this yielded n = 15 families (31 total interviews; 21 parents, and 10 youth) whose interview responses were thematically analyzed. A flow chart of participating families is shown in Figure 1. Demographics of the 23 retransitioning youth are shown in Table 1 separated by whether they did or did not participate in interviews. We describe additional details about the nonparticipating families in the discussion.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of participating families3.

Table 1.

Sample demographics.

| Participated in interviews | Did not participate in interviews | |

|---|---|---|

| n = 15 | n = 8 | |

| Youth Age in Years, M (SD) | 11.3 (2.2)* | 12.1 (3.1)^ |

| Assigned Sex at Birth | n (%) | n (%) |

| Male | 10 (66.7%)† | 5 (62.5%)† |

| Female | 5 (33.3%) | 3 (37.5%) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Multiracial | 3 (20%) | 2 (25%) |

| White, Hispanic | 3 (20%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 9 (60%) | 5 (62.5%) |

| Annual Household Income | ||

| <$50,000 | 4 (26.7%) | 3 (37.5%) |

| $50,001–$75,000 | 2 (13.3%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| $75,001–$125,000 | 5 (33.3%) | 2 (25%) |

| >$125,000 | 4 (26.7%) | 2 (25%) |

| Parent 1 Highest Level of Education | ||

| High School Diploma | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Some College/Associate’s Degree | 2 (13.3%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| College Diploma (Bachelor’s Degree) | 3 (20%) | 3 (37.5%) |

| Advanced Degree (MA, MD, PhD) | 9 (60%) | 3 (37.5%) |

| unknown | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.5%) |

at interview (based on whichever family member participated first).

at study cutoff date (Jan 1, 2021).

The proportion of assigned male youth in this study aligns with the proportion of assigned male youth in the broader longitudinal sample (65.6% assigned male, see Gülgöz et al., 2019).

Of the 8 families who did not participate, 3 did not respond to the invitation, one responded to the invitation and filled out consent forms but could not be reached for scheduling, one declined for mental health reasons, one declined for confidentiality reasons, one declined without providing a reason, and one was not invited (see above, family had not been in touch with research team in approximately five years). All qualifying youth, their interview participation status, and the ages at which they socially transitioned and retransitioned, are summarized in Table 2.

Interview procedure

We completed hour-long (or less), semi-structured interviews with participating families on a rolling basis between December 2018 and November 2020, except for the one participant who participated in the previous round of phone interviews in July 2017. The structure of the 2017 interviews were similar enough that the responses of this participant could be coded and included in the results of the present study.

Interviews were usually conducted over the phone (26 interviews) but were sometimes conducted in person (5 interviews), depending on the geographic location of the family and travel schedule of the research team. Interviews were conducted one-on-one, by a member of the research team with each participant. The members of the research team who conducted interviews were the principal investigator, a postdoctoral researcher, a doctoral student, and a lab manager. Interviews were audio recorded and subsequently transcribed and de-identified by research assistants. Each participant was compensated either $15 or $20 for their participation (the hourly payment for participating in the study was increased part way through data collection when the research team moved institutions). Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Washington and Princeton University. Informed consent was obtained from parent participants, and assent was obtained from youth participants.

The parent and youth semi-structured interviews followed a similar structure. Participants were asked questions about (1) what led up to each transition, (2) the reactions within the youth’s social environment to each transition, and (3) the participant’s general reflections on the entire experience—including positives and negatives of the entire process and any advice they would give another youth/family on a similar journey. The 2017 round of interviews, from which data for one of the families were utilized because they did not participate in the later interviews, asked questions about the child’s social transition(s), gender expression, wellbeing, and social relationships at various points in the child’s life.

Thematic analysis

The authors followed the six-phase framework for thematic analysis outlined by Braun & Clarke, 2006. The first author reviewed the interview transcripts (phase 1) to create an initial draft of a coding scheme (phase 2), which included qualitative codes (e.g., “Child made a statement (e.g., ‘I am a girl’)/brought it up,” yes = 1, no = 0), as well as quantitative codes (e.g., how positive or negative was the school’s response to a transition, on a scale of 1–5). Next, each member of the coding team, which was made up of a postdoctoral researcher, a graduate student, a lab manager, and a senior thesis student, read through the interview transcripts of five randomly selected families—stratified by participant gender (cisgender, nonbinary, binary transgender)—with the goal of identifying new codes and refining existing codes (phase 2). After reviewing the interviews of the five randomly selected families and modifying the codebook accordingly, the codebook was finalized.

Next, the coding team worked in pairs to code each interview. First, the two coders coded each interview independently of one another; next, they met to discuss discrepancies and reach consensus. For two families’ interviews, the coding could not be done independently, because those families’ interviews had been used for coders to practice discussing their impressions as a group. In cases in which consensus could not be reached, the coders consulted the principal investigator for assistance reaching consensus.

Finally, the first author reviewed the coding data produced by the coding team to search for, and begin to organize, the data into themes (phase 3), then reviewed and refined the themes (e.g., “Social inputs to gender,” see Results section) with input from coauthors (phases 4 and 5), and then wrote up the report of the thematic analysis (phase 6).

The final report of the thematic analysis centers around three domains of the interview: (1) what led up to each transition, (2) the reactions of the youth’s social environment to each transition, and (3) the participant’s general reflections on the entire experience—including positives and negatives of the entire process and any advice they would give another youth/family on a similar journey.

Results

Results section 1: Antecedents of social transitions

In their semi-structured interviews, participants were asked about what led up to each of the child’s social transitions. Coders coded the antecedents each participant mentioned for each of youth’s social transitions.

Regarding what led up to youth’s first transitions, youth commonly described that they told someone about how they felt (see code, “child made a statement”); youth also commonly spoke about their internal sense of their gender identity (see code, “child’s internal gender identity experience”). Parents commonly described that the youth had gender nonconforming preferences/presentation prior to the first transition (see code, “child’s gender preferences/presentation”), and parents also often recounted youth saying something about their gender, for example saying something like “I am a girl” or “I think I am a boy” (see code, “child made a statement”).

Regarding what led up to retransitions (2nd, 3rd transitions), youth again frequently spoke about their internal gender identity experience, and they often described having made a statement about their gender, for example telling their parents they were actually nonbinary. Parents also frequently remembered the child having made a statement about their gender; additionally, parents often talked about the youth’s gender preferences/presentation changing before retransitions.

For a list of reported antecedents to transitions, as well as the frequency with which each antecedent was mentioned, see Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Antecedents of 1st social transitions.

| Code | No. of youth participants who mentioned code | No. of parent participants who mentioned code |

|---|---|---|

| n = 10 youth interviews reporting on 10 initial transitions | n = 21 parent interviews reporting on 21 initial transitions | |

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Child made a statement (e.g., “I am a girl”)/brought it up | 7 (70.0%) | 19 (90.5%) |

| Parent inquired about/suggested/explained the options | 1 (10.0%) | 11 (52.4%) |

| Child’s gender preferences/presentation (peers, toys, clothing, hairstyle) | 4 (40.0%) | 19 (90.5%) |

| Child role-played/identified as different gender in fantasy play (could be on the internet) | 1 (10.0%) | 6 (28.6%) |

| Someone else brought it up (e.g., therapist, support group, teacher, parent’s friend) | 0 (0%) | 2 (9.5%) |

| Went to a therapist/support group about gender (child or parent) | 1 (10.0%) | 9 (42.9%) |

| Child mental health/wellbeing/behavior issues that seemed to be related to gender | 1 (10.0%) | 11 (52.4%) |

| Gender segregation (e.g., boys’ and girls’ sports, boys’ line vs. girls’ line) in school or other activity brought it up | 1 (10.0%) | 2 (9.5%) |

| Issues related to body/puberty/hormones/blockers | 0 (0%) | 2 (9.5%) |

| Learned about a new identity (e.g., gay men, lesbians, nonbinary) | 1 (10.0%) | 3 (14.3%) |

| Met a role model of a particular gender / LGBT identity | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.8%) |

| Child’s internal gender identity experience | 5 (50.0%) | 1 (4.8%) |

| Child wanted to live authentically | 2 (20.0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Peers — acceptance or rejection from peers of one gender (e.g., being bullied by the boys; being accepted by the girls) | 0 (0%) | 3 (14.3%) |

| People were misgendering them/were transphobic toward them in previous gender | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.8%) |

| Believed gender expression had to align with gender identity (e.g., believed feminine people had to be girls) | 1 (10.0%) | 2 (9.5%) |

| Child thought it would be cool/edgy/make a political statement to transition | 1 (10.0%) | 0 (0%) |

Table 4.

Antecedents of 2nd and 3rd social transitions (combined).

| Code | No. of youth participants who mentioned code | No. of parent participants who mentioned code |

|---|---|---|

| n = 10 youth interviews reporting on 13 retransitions | n = 21 parent interviews reporting on 26* retransitions | |

| n (%)^ | n (%)^ | |

| Child made a statement (e.g., “I am a girl”)/brought it up | 5 (38.5%) | 18 (69.2%) |

| Parent inquired about/suggested/explained the options | 2 (15.4%) | 4 (15.4%) |

| Child’s gender preferences/presentation (peers, toys, clothing, hairstyle) | 3 (23.1%) | 9 (34.6%) |

| Child role-played/identified as different gender in fantasy play (could be on the internet) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Someone else brought it up (e.g., therapist, support group, teacher, parent’s friend) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.8%) |

| Went to a therapist/support group about gender (child or parent) | 1 (7.7%) | 3 (11.5%) |

| Child mental health/wellbeing/behavior issues that seemed to be related to gender | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.8%) |

| Gender segregation (e.g., boys’ and girls’ sports, boys’ line vs. girls’ line) in school or other activity brought it up | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.8%) |

| Issues related to body/puberty/hormones/blockers | 0 (0%) | 6 (23.1%) |

| Learned about a new identity (e.g., gay men, lesbians, nonbinary) | 3 (23.1%) | 8 (30.8%) |

| Met a role model of a particular gender / LGBT identity | 0 (0%) | 2 (7.7%) |

| Child’s internal gender identity experience | 6 (46.2%) | 5 (19.2%) |

| Child wanted to live authentically | 1 (7.7%) | 1 (3.8%) |

| Peers — acceptance or rejection from peers of one gender (e.g., being bullied by the boys; being accepted by the girls) | 0 (0%) | 5 (19.2%) |

| People were misgendering them/were transphobic toward them in previous gender | 1 (7.7%) | 6 (23.1%) |

| Believed gender expression had to align with gender identity (e.g., believed feminine people had to be girls) | 2 (15.4%) | 2 (7.7%) |

| Child thought it would be cool/edgy/make a political statement to transition | 1 (7.7%) | 0 (0%) |

The reason this adds up to such a large number is that sometimes two parents participated, and some youth made second and third transitions. Thus, as an example, two parents reporting on their child’s second and third transitions counted as four possible reports on retransitions.

The raw numbers report the number of times a given code was mentioned, summing across second and third transitions. The percentages represent the number of times a code was mentioned out of the total number of times it could have been mentioned.

Thematic Analysis. The authors identified superordinate themes from participants’ responses about what preceded each social transition.

Theme 1. Evolving gender identities

Some youth said that they socially transitioned again because their internal sense of their gender identity changed over time. For example, one nonbinary youth, who previously lived as a binary transgender girl, described that they had felt completely female when they were younger, and they now feel somewhere in between male and female.

Youth (age 11) currently using they/them pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

…on a scale, I…would say I was pretty close to female…and about on the opposite—about as far as you can be—from male…so…I made like a huge jump [from their assigned sex male, to female]. And now I would say I am slowly getting back to…the center…between the two…I’d say I’m still closer to…female, but I would say I’m pretty close to…halfway.

A cisgender boy, who had lived as a transgender girl for a period, described feeling like a girl during the time he was living as a girl, and later starting to feel more like a boy.

Youth (age 9) currently using he/him pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

They [youth’s parents]…asked me, I can go back to being a boy whenever, and I still said, “no, I still feel like a girl.” But then when I got older to now, I felt more—I noticed and felt more like a boy.

A nonbinary youth described that, after living as a girl for a period, they started feeling like living as both/neither of the binary genders would be a better fit.

Youth (age 11) currently using they/them pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

…I am pretty sure it happened in 4th grade—like, before 4th grade—and, I don’t know, I just didn’t want to be a girl anymore, and I didn’t want to be a boy, so I decided just to be smack-dab in the middle.

In contrast, a cisgender boy seemed to indicate that his internal sense of his gender identity did not change across transitions, and that he did not feel right during the period in which he was living as a girl.

Youth (age 12) currently using he/him pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

…when I was a girl…I didn’t really feel—like I was a happy kid, but I just didn’t feel like I was meant—I didn’t feel right as a girl…it was always like a burden rather than something that I really strongly felt. Like that was who I was.

Theme 2. Social inputs to gender

Many participants described inputs from youths’ social environment that played a role in helping them to refine or label their identity.

A nonbinary youth, who had socially transitioned to live as a binary trans girl for a period, described the impact of meeting a nonbinary person for the first time.

Youth (age 13) currently using they/them pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

…then my second therapist was nonbinary, and I asked my mom why she was using they/them instead of…she/her or he/him for them. And she…explained what nonbinary was, and I was like, “hey, that sounds familiar! I do that!”

Another youth described a similar experience—that seeing other people use they/them pronouns helped them figure out how they identified.

Youth (age 13) currently using they/them pronouns who entered the study as a transgender boy and later used she/her pronouns

Seeing other people do it…I kind of felt—this is who I am, but like I had never seen…that, in the past, so I didn’t…know that could be me, you know?

A parent of a cisgender boy, who had previously lived as a transgender girl for a period, reported that the youth saw a children’s anime show featuring gay youth, and through this he learned about the concept of being gay. This prompted a conversation with his parent about what it means to be gay, after which he told his parents that he thought he was a gay boy, not a trans girl.

Mother of a youth (age 9) currently using he/him pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

And…then he’s like, “what exactly does it mean to be gay?” He asked the question, so I was like, “okay good, let’s talk about it.”…but it wasn’t for several weeks that…he eventually talked to [other parent’s name] about it…it was basically—he said he thinks he’s gay and not a girl.

Sometimes, participants described that a more harmful kind of social input—bullying and misgendering—preceded a child changing their pronouns or gender presentation.

One parent described that her child switched from using they/them pronouns to the pronouns assigned at birth (she/her) at school, and this change may have been motivated by the teacher’s failure to use they/them pronouns.

Mother of a youth (age 14) currently using she/her and they/them pronouns who entered the study as a transgender boy and later used he/him and they/them pronouns

…just recently, when they [the youth] said she/her, I really think that that was…mostly for ease at school because it was really hard with—nobody used they/them as far as…teachers and stuff…Teachers are not good with that.

Later, the parent further described her reaction to this change.

…I get confused about—is this what’s authentically happening with my kid, or is it because it’s really hard to be in society as a trans person, and this is easier?

Another child, who lived as a binary transgender girl for a period, announced one day that he wanted to live as a boy again, and soon he did so. Afterwards, his parent found out that—during the time the child was living as a trans girl—he was bullied at school (e.g., being told he could not be a girl because he had a penis) and consistently misgendered by one of his teachers. After returning to he/him pronouns, he still experienced body dysphoria and had some stereotypically feminine interests, but he hid them in public.

Mother of a youth (age 6) currently using he/him pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

…he’s much more likely to display some gender non-conforming behaviors when there’s no other peers or grandparents or whatever around. So like, for example, he has…a shirt that’s…purple…he wouldn’t wear that to the playground, but he will wear that at home. Um, or he really enjoys…makeup and so he’ll do makeup, but not if we’re gonna go out. Um, so…he definitely…keeps the things that would…be perceived as more female-typical…to more private times.

Later, the youth’s parent wondered about how he might identify in the future.

…it would be not at all surprising to me if in the future he ends up identifying as nonbinary, or…maybe sort of a more binary trans person, I don’t know…I feel like his gender presentation right now is quite a bit performative, and I wish it weren’t that way. I mean I wish it was—it just felt safe to be whatever.

Results section 2: Others’ reactions to youth’s social transitions

Coders also rated participants’ responses about how positive vs. negative various people’s reactions were to each of the youth’s social transitions; coders rated participants’ responses on a scale of 1–5. On the 1–5 scale, a 1 corresponded with a very negative reaction, a 3 corresponded with a neutral or mixed (some positive, some negative) reaction, and a 5 corresponded with a very positive reaction. Of note, after long discussions, the coding team decided that a neutral response (a 3 on the 1–5 scale) also encompassed nonchalant reactions (e.g., a child announcing their gender identity and the parent saying “ok”) and non-reactions (e.g., kids at school either not realizing, or not caring that the child’s gender had changed). Thus, a 3 often encompassed an accepting reaction, and what many might consider an ideal reaction of not making a big deal out of it, but it did not include an overtly positive response (e.g., a celebration).

In general, both youth and parent participants reported that on average people reacted neutrally (often nonchalantly), or slightly positively, to both the child’s first and later social transitions. Means and standard deviations of each group’s reactions to first and later social transitions, by reporter, are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Mean reactions to youths’ social transitions from their social environments.

| Youth reported | Parent reported | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reactions to 1st Social Transitions | ||||||

| n | M | SD | n | M | SD | |

| Parent | 6 | 3.83 | 0.75 | 15 | 3.40 | 0.60 |

| Sibling | 1 | 3.00 | 7 | 4.00 | 0.87 | |

| Peer | 5 | 2.40 | 0.89 | 10 | 3.00 | 0.78 |

| School | 2 | 3.50 | 2.12 | 11 | 3.41 | 1.24 |

| Extended Family | 0 | 14 | 2.89 | 0.53 | ||

| Other Adults | 0 | 13 | 3.42 | 1.15 | ||

| Reactions to 2nd and 3rd Social Transitions (Combined) | ||||||

| n | M | SD | n | M | SD | |

| Parent | 5 | 3.80 | 0.84 | 15 | 3.23 | 0.56 |

| Sibling | 1 | 4.00 | 5 | 2.80 | 0.84 | |

| Peer | 5 | 3.20 | 0.84 | 13 | 3.04 | 0.99 |

| School | 1 | 2.00 | 10 | 3.55 | 0.83 | |

| Extended Family | 1 | 1.00 | 11 | 3.32 | 1.06 | |

| Other Adults | 0 | 10 | 2.95 | 1.26 | ||

Note: 1 = negative, 3 = neutral or mixed, 5 = positive.

Thematic Analysis Related to Reactions to Youth’s Later Social Transitions. The authors identified superordinate themes from descriptions of people’s reactions to the youths’ later (2nd or later) social transitions.

Theme 3. Acceptance

Reactions to a youth’s retransitions were often accepting, and in instances where youth were worried about others’ reactions or received negative reactions from others, accepting people were sometimes able to step in and help.

One parent described her accepting reaction when her child told her they wanted to go off puberty blockers, an initial indication that the youth wanted to retransition.

Mother of a youth (age 13) currently using they/them pronouns who entered the study as a transgender boy and later used she/her pronouns

…my reaction was mostly just really wanting to help my child feel secure in who they are no matter who they are and wanting to give them enough space, like emotional and psychological space and safety at home, to be able to really explore questions of identity.

Another parent described her nonchalant acceptance of her child announcing they wanted to switch to they/them pronouns.

Mother of a youth (age 14) currently using they/them pronouns who entered the study as a transgender boy

…they just came out to me in front of other people at school, and you know, “I want to be called [youth’s name],” and I said “alright,” “and say they pronouns,” “alright.” That’s all we had to do the second time.

One parent described that she was shocked when her—at the time, binary trans daughter—announced a desire to transition to live as a cisgender boy. Despite her shock, the parent was ultimately accepting of the youth’s desire to retransition.

Mother of a youth (age 9) currently using he/him pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

I think I was probably more shocked than [other parent’s name]…I was stunned honestly. And so I—and like I said, I’d noticed that he had been wearing less sparkly things—but…I just thought that was just a function of getting older…I was stunned, and it kinda took me a couple of days, but then I thought, “you know this is who he is, and we transitioned once, we can transition back.”

Some youth had not disclosed their identity as a trans person in all parts of their lives, particularly at school, before retransitioning, a factor that could potentially impact others’ reactions. In certain contexts, youth ended up explaining that they were transgender for the first time when they were retransitioning.

One such youth returned to using their assigned pronouns at birth (she/her) for a period after living as a transgender boy for a while (they currently use they/them pronouns). At the time they were retransitioning to adopt she/her pronouns, they felt nervous to do so at school because only a few classmates knew they were transgender to begin with. The youth decided to turn to their teacher for help, who was very accepting, as were their classmates.

Mother of a youth (age 13) currently using they/them pronouns who entered the study as a transgender boy and later used she/her pronouns

…this amazing fifth grade teacher did this…two-week long unit on gender…showed a lot of really good YouTube videos and…asked [youth’s name] and us to weigh in about…the content…and then that made it easy. Actually, the last day of the unit was a Friday, and [youth’s name] raised their hand and said, “Miss [teacher’s name], I’m ready!”

In response, the youth’s classmates reacted very positively.

The class actually cheered and clapped when they told them, and this kid who [youth’s name] was really, particularly worried about…said…“if anybody comes at you, we got your back.”

Another youth, who had not disclosed that he was transgender at school, explained via chain mail message2 that he had been living as a transgender girl and would return to school as a cisgender boy. In response, kids at school generally reacted with acceptance.

Youth (age 12) currently using he/him pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

…my friend had this idea to send out…a chain mail message, and so I wrote one up explaining…what was going on, hopefully that it would reach people. So that I would come back to school and have most or all people know that I was a boy…it went great. And then when I came back to school…most people knew. Um, my friend was on Instagram, and she said that people were posting it on Instagram…nobody really bullied me or anything. It was either just support or…ignore.

Another parent described that—because some people at school did not know her child was transgender to begin with—some people believed that he was transitioning to be a transgender boy, when in fact he was transitioning to his gender assigned at birth. This resulted in a transphobic reaction from another parent, but the youth’s accepting principal was able to intervene.

Mother of a youth (age 9) currently using he/him pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

…so since he [initially] transitioned before he started [kindergarten], he had always been a girl at school, so, there were—we heard about kids saying that, “oh [youth’s name] had gotten a penis sewn on”…or something else. I mean just, you know, as much as they are able to conceive of a transgender person. I think some of the kids think he is a trans boy. Like that he is a biological girl. And…the principal let us know that one parent had called her and said…something like, “I, I hear there’s a…girl pretending to be a boy or something in your school,” and [principal’s name] rightly said “nope.”

Theme 4. Relief

Sometimes participants described positive reactions to a youth’s retransitions—particularly when the youth was retransitioning to their gender assigned at birth—that seemed motivated by relief that the child was no longer transgender. These feelings sometimes seemed to be driven by the belief that the child would not have to experience challenges associated with being transgender (e.g., making decisions about medical transitions, experiencing transphobia).

A parent of a child who returned to the pronouns assigned to them at birth for a period (and currently uses they/them pronouns) reported that extended family members seemed relieved during the period that the youth returned to the pronouns assigned to them at birth.

Mother of a youth (age 13) currently using they/them pronouns who entered the study as a transgender boy and later used she/her pronouns

…extended family, it was almost like across the board, there was this huge sigh of relief that people were like, “oh it’s over.” That was weird, that was very bizarre …and I don’t think [youth’s name] necessarily felt that um, but that’s definitely my observation, that people seemed relieved.

Another parent described that both she and her extended family felt relieved upon her child’s retransition to his gender assigned at birth due to assumptions that being cisgender would be easier than being transgender.

Mother of a youth (age 9) currently using he/him pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

…extended family were all probably very relieved…like…“[parent’s name]’s child doesn’t have to go through the hardships associated with, you know, being transgender.” Like, that is a relief. I was relieved.

One parent described feeling relieved that her child retransitioning meant her child wouldn’t have to make decisions around medical transition.

Mother of a youth (age 10) currently using she/her pronouns who entered the study as a transgender boy

I felt relieved, only because I was so worried that the decisions that would be coming up, pre-puberty.

Another parent reluctantly described that she felt relieved upon her child retransitioning, given how dangerous the world is for trans women.

Mother of a youth (age 9) currently using he/him pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

…then, as he’s transitioned more toward being cis male, possibly gay?…it’s really sad to say this, but I felt like a little bit of a weight was lifted off of me, and that really makes me feel bad, but it’s just—the world is so much kinder to gay men than trans women, so…it really—I was less scared for him. Still scared because being gay now is difficult, but less scared…about his prospects of violence toward him.

Theme 5. (Society’s) difficulty outside the binary

Among participants who transitioned to nonbinary identities/pronouns, participants often described that people struggled to adjust to youth’s nonbinary identity and/or they/them pronouns. One youth described the constant questioning they are subjected to about their nonbinary identity.

Youth (age 13) currently using they/them pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

And then there’s just the ever-present, ever-annoying, “so you’re a boy?” “No.” “So you’re a girl?” “No.” “So you’re a boy?” “No.” And that goes on for—and this is my top score here—I think about 15 minutes before they get bored or just say, “okay so you’re a girl,” and I can’t stop them at that point. And they just refer to me as a girl. And that’s just always annoying.

One youth’s parent described that she felt society was more judgmental about having a nonbinary child (vs. a binary trans child) and a child who transitioned more than once.

Mother of a youth (age 13) currently using they/them pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

…it just felt like there was a whole other layer of judgement…it was definitely more of a psychological thing for me with people judging [the nonbinary transition] like, you know “you’re just going to let your kid do whatever,” and “this is going too far,” and “how many times is this going to change”—that sort of [thing]…and we lost people who had previously been supportive.

Many participants reported that various people—parents, peers and schools—had trouble adopting they/them pronouns.

Mother of a youth (age 9) currently using they/them pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

…I think a lot of the kids in their classes didn’t use them [the youth’s pronouns]…and so, and their teacher used they/them pronouns, but…it seemed to slip through the cracks with the kids.

A parent of a nonbinary youth described that he and his wife initially had trouble with they/them pronouns but improved over time.

Father of a youth (age 10) currently using they/them pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

…as soon as they informed us that they really felt more they/them, they gave some grace period for different people. So their…spiel was…“I’m a they/them, I’m nonbinary, but she/her is okay”…a couple months—a few months—went by [in which parents continued to use she/her pronouns], and my wife and I talked and talked about—if anybody was going to affirm their preferences, it should be us. And so even though she/her was stated as okay, we really worked hard to transition all the way, our language, so that it actually fit their preferences.

Results section 3: General reflections on the multiple transitions journey

At the end of the semi-structured interviews, both youth and parents were asked to reflect more generally on the youth’s entire gender journey/process. Participants were asked to speak to the general positives and negatives of the entire process, to describe their emotional experience throughout the journey, and to share any advice they would give to another child or family on a similar journey.

Theme 6: Importance of support from, and narratives by, the trans (and trans-affiliated) community

Many participants spoke to the importance of support from transgender people, as well as the importance of media representation of transgender people, throughout their journey.

One transgender boy described that meeting other transgender people was one of the most positive parts of his experience.

Youth (age 10) currently using he/him pronouns who entered the study as a transgender boy and later used they/them and he/him pronouns

…I’ve met more people, like, I met a counselor who talked about it with me, and they were nonbinary. And then I met another kid who had also transferred from she/her pronouns to he/him. So I…was meeting more people who actually had experiences like me.

A parent of a nonbinary child described the importance of representation of nonbinary people in media for her child.

Mother of a youth (age 10) currently using they/them pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

…one of their favorite…people right now is Jonathan Van Ness, you know, recently came out as nonbinary also and so, you know, I think he is a great example of somebody who gets to play around with gender, and…I love that [youth’s name] looks at them, you know, looks at him in that way and feels—has a positive example of somebody who wears a skirt and has a beard…

Another parent referenced the importance of friendships with transgender people, as well as with parents of transgender children.

Mother of a youth (age 14) currently using she/her and they/them pronouns who entered the study as a transgender boy and later used he/him and they/them pronouns

…we also have a…large community of support for people who also have trans kids or, you know…we have a lot of transgender friends and nonbinary friends too, and that…helps me know more, like…[have] this different base that I’m starting from…

One parent described unsupportive/unhelpful reactions from the trans and trans-affirming community. She described that support from the community disappeared when her child retransitioned to his gender assigned at birth.

Mother of a youth (age 9) currently using he/him pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

…it [community support] all went out the door as soon as my child went back to, like, not trans. Like, wait—we’re supposed to be open minded and accepting, and that includes a detransition. Like I, I support my child regardless, I thought that was what we were supposed to do….

Theme 7: Reflections on the initial transition decision (in light of later transitions)

When asked to give general reflections, only a handful of participants directly addressed whether they thought the first (or any) transition had been the right vs. wrong decision in light of the youth retransitioning and/or whether they regretted any of the youth’s transitions.

A parent of a child who retransitioned to live as a cisgender boy explicitly stated that she did not regret her child’s initial transition.

Mother of a youth (age 12) currently using he/him pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

So, I think I will pass along some advice that a friend gave me…“you don’t know unless you try.” And I said, “well what if it was the wrong one?” “Well then at least you know. And maybe it isn’t.”…I don’t regret the transition.

One parent did report worrying, in retrospect, that his child’s initial transition could have been a mistake. Specifically, he described worrying that his child might have always wanted to be a cisgender boy (with feminine preferences), rather than a transgender girl, and that the parents may have steered things in the wrong direction.

Father of a youth (age 12) currently using he/him pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

And probably the biggest concern I’ve had through this whole thing is…that maybe we steered this whole thing wrong. And I don’t think that we’ll ever really know if what we did was the right thing or not. And that’s hard as a parent to reconcile.

Later, reflecting on the child’s initial social transition to live as a transgender girl, he said:

That’s the choice that we took. And I would say that we definitely did not do anything to force it, but we also didn’t do anything to encourage the other path.

Two separate parents expressed that they disagreed with their child’s initial transition at the time that it happened, but also that they do not regret their child’s initial transition.

One of these parents described her incredulity around her (currently nonbinary) child’s initial transition to transgender girl.

Mother of a youth (age 13) currently using they/them pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

…I will say that when [youth’s name] [first] transitioned…it didn’t feel quite right to my partner and myself…they had used the language of “half boy, half girl” and…had partially been just so adamant that they were a boy, that…it didn’t feel quite right to us…so you know it felt like it was us and a gut feeling against the people who were supposed to be the specialists…so we went with it, and…at the time [youth’s name] seemed happy to do that.

Later, she expressed that she did not have regrets regarding the process/journey.

…I don’t regret how we did it. You know, a lot of people want us to have pushed back harder and not accepted who they were, and I don’t regret that at all…yeah, I don’t have any regrets. You know, if anything…I know that it takes time to make the transition with pronouns, and…I wish we could have been faster with it…

The second of these parents, a father, described that he had always perceived his child as “just a tomboy,” and thought her first transition to transgender boy had been unwarranted.

Father of a youth (age 10) currently using she/her pronouns who entered the study as a transgender boy

…my whole thing has been, I thought she was just like a hard-core tomboy. And then, that’s…where I’m looking at it from. Because I had one of my best friends growin’ up—she was a hard-core tomboy…If I say something to [other parent’s name] about it, she’ll get pissed off at me because oh I’m not accepting or whatever, and it’s like…I am. I’m cool, but I don’t think it [being transgender] necessarily applies to our child.

Later though, he expressed feeling glad that his child had experienced living as a boy, even though she no longer does.

…[other parent’s name] kinda…jumped the gun on that. But oh well, I’m kinda glad they figured it out…Because otherwise…we’d never know, you know? She would have been like, “oh maybe I am a boy” her whole life. And like hey—we’ll see how it goes. And if you like it, then just…if that’s you, then that’s you. If it’s not, then—if it’s not you—you can change it back.

In sum, three parents expressed varying degrees of ambivalence about their children’s initial social transitions. In two cases of ambivalence, the parents ultimately ended the interview by stating they did not regret the initial transition or saw it as having been useful in the child’s recognizing their current identity, while the third parent seemed to feel a continued sense of uncertainty about whether the initial transition had or had not been the right path.

Theme 8. Follow the child’s lead

When parents were asked to give advice to other families on a similar journey, most parents spontaneously advised other families to follow the child’s lead. This answer seems to indicate satisfaction with how the process went, or lack of regret, with overall transition journeys.

Mother of a youth (age 9) currently using they/them pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

…I’m really glad that we kinda were just like, “okay, let’s just go with the flow, and let’s see, you know, where our kid is taking us.” And we’ve learned to follow…our child’s lead.

Mother of a youth (age 14) currently using she/her and they/them pronouns who entered the study as a transgender boy and later used he/him and they/them pronouns

…I think the hardest thing for me, especially when there was like switching back and forth with pronouns and with hormones and all that stuff, was that it was really hard work to trust the process…but really, if you could, let your kid lead, in everything, like in everything—obviously they can’t make their own choices about everything, like they can’t decide their dose of testosterone or whatever—but some kids really do need to try these things to see if they work, or if they don’t work.

Several parents also mentioned the importance of overcoming one’s own reactions, expectations, etc. in order to follow the child’s lead.

Mother of a youth (age 9) currently using he/him pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

I would just say listen to your kids. Follow their lead. You know, having gone through four-and-a-half years as a boy, four-and-a-half years as a girl, and now back to being a boy, it’s—you just, you gotta listen to your kid. You’ve gotta follow their lead. Even if it’s hard for you personally…You know like if…you’re having big feelings about it, go vent to other adults outside of your kid’s presence, but always show support to your kid. No matter what.

Father of a youth (age 10) currently using they/them pronouns who entered the study as a transgender girl

…I guess the…dad advice…that I could give…to any other dad, or any other parent that is having a hard time with it: it’s not always about you. The point—us guys like to make it about us, let’s face it. Yeah, and in this case it just…was not about me. And as soon as I accepted that, a lot of stuff I was able to let go of and just show up for my kid.

Discussion

The present study describes the experiences of children who initially socially transitioned to live as binary transgender children, and who later retransitioned. Retransitioned youth represent 7.3% of our larger sample of 317 children (including 1.3% who transitioned a third time and currently are binary transgender youth) who had originally socially transitioned for the first time between the ages of 3 and 12. These retransitioning youth and their parents described various factors preceding retransitions, including that youth started to identify differently, that they learned about a new identity or pronouns (e.g., learning what it means to be gay, or hearing about they/them pronouns for the first time, etc.), and/or that they experienced transphobia. Reactions of the people in youth’s lives to their retransitions varied, but on average, people in the child’s environment reacted neutrally or slightly positively to youths’ retransitions. Looking back on the experience, only a few parents reported questioning whether the initial transition had been the right decision and, even then, all but one leaned toward thinking that the initial transition had been a key part of the youth’s journey, nonetheless. Notably, no youth indicated that they regretted their earlier transitions or retransitions. When asked to reflect on the entire process, parents overwhelmingly stressed the importance of following the child’s lead, thereby implying satisfaction with their family’s transition journey.

The possibility of retransitions has sometimes been used to argue against childhood social transitions in general (de Vries & Cohen-Kettenis, 2012; Steensma & Cohen-Kettenis, 2011). Authors have expressed concern that childhood social transitions may commonly result in distressing retransitions, and previous work shows that changing one’s gender expression can lead to social rejection (Coleman et al., 2012; Steensma et al., 2011; Steensma et al., 2013; Steensma & Cohen-Kettenis, 2011). Scholars have also wondered if some children who socially transition will feel permanently locked into a transgender identity, be “set on a course toward a lifelong gender transition” (Green, 2017, p. 81).

The present work largely does not provide evidence for these possibilities (though of course some individuals outside of this study could have negative experiences with retransition that are not reflected here). We find that few of the (initially) binary transgender children in our broader study have thus far retransitioned (Olson et al., 2022). For those youth who have retransitioned, we found that many experienced accepting (whether neutral or positive) reactions to retransitions, and people’s reactions to retransitions were often similar in valence to their reactions to initial transitions. In some cases, youth’s social environments responded even more positively to retransitions than they did to initial transitions—for example, people who reacted negatively to a youth’s first social transition and then expressed relief when the youth retransitioned. In cases where participants reported experiencing negative reactions, they described others’ lack of understanding of nonbinary identities, as well as judgments that their parenting was overly permissive, and/or their family’s loss of place among previously supportive communities. Finally, regarding the concern that social transitions in childhood may put children “on a course toward a lifelong gender transition” (Green, 2017), the present study exemplifies that at least some youth feel able to retransition after a childhood social transition (whether some socially transitioned youth want to retransition, but do not, cannot be answered by the present study).

Beyond how these data on retransition apply to debates about childhood social transitions in general, we hope that the data reported here underscore the legitimacy of retransition trajectories, exemplify (some of) the varied experiences of youth who retransition that are less often discussed, and will help clinicians and parents better support youth who retransition (Hildebrand-Chupp, 2020). We also hope these data are considered in conjunction with the experiences of the other youth in the larger study, the majority of whom have not (thus far, at least) retransitioned.

Several factors limit the present findings and their generalizability. As with all research, it is important to acknowledge that aspects of this study—including what questions we deemed relevant to ask, what codes and themes we identified within participants’ responses, and how we rated the reactions of people in youth’s social environments—reflect the subjective perspectives of the members of the research team. Our perceptions are informed by our own positionalities, which include being transgender and cisgender; women and men; heterosexual, lesbian, and bisexual; White, Black, and Latina; Jewish, Christian, and non-religious; with and without disabilities. Qualitative work is also influenced by participants’ own subjective understandings of their and their families’ narratives. The subjectivity of qualitative work is often seen as both a strength and a limitation and reflects why this and other work can benefit from a mix of qualitative and quantitative data.

Next, the larger longitudinal study from which these participants were drawn is not a representative sample of transgender youth in general. Because the longitudinal study recruited children who made binary social transitions in childhood, the sample skews toward youth who experienced high levels of (at least family) support, without which children cannot socially transition at these early ages (e.g., they require that a parent speak with the school about changing the child’s name and pronouns). Further, this sample is mostly comprised of parents who are highly educated, and few families are lower income. In contrast, many transgender youth receive little family support (Grossman et al., 2005, 2011) and have fewer resources, which limits their access to supportive schools and mental health care (Gill-Peterson, 2018). It is possible that youth who experience discrimination across other dimensions, like socio-economic status, experience less support throughout their transition journeys and have qualitatively different experiences than those captured here.

Another limitation is that we spoke to only 15 of the 23 families with youth who retransitioned. Amongst those with whom we did not speak are three families whose children currently live as cisgender youth—the group about which there is most discussion in the literature and in society broadly. It is possible that there could be a bias in who was willing to participate in this study, such that those with more regret did not want to discuss their transitions. While this is possible, we have reason to doubt that explanation given other contacts we have had with these families through their participation in the broader longitudinal study (e.g., online surveys, Zoom study visits, email communication). For example, one of these parents whose family did not participate in these interviews wrote in a recent survey that their child is “back to sex at birth but still fluid,” and described the youth as “happy, healthy, and kind…loved, and always fully supported and affirmed.” The parent of another currently cisgender youth provided an update via email, writing that her child “still likes his girly things but seems to be perfectly comfortable as himself at this point. He tells us that he ‘may be [youth’s former, transitioned name] again when he’s grown up but right now he’s [youth’s current name].’” The parent of the final currently cisgender youth described in a recent visit that—like other youth described in this study (see Theme 2. Social inputs to gender)—her child experienced transphobia that may have influenced her child’s retransition. He retransitioned after being suddenly outed as transgender at school, and after being consistently misgendered by his teacher. This youth now says he is a boy most of the time and has also expressed that he may be both a boy and a girl. Taken together, while it is a limitation that we did not interview every family who qualified for the study, we suspect that some of the experiences we did not capture may overlap with the themes already described in this paper. Further, these families have not dropped out of the study and may therefore be involved in future interviews.

These findings are also limited by the fact that they rely more on parent than on youth report. Given the young age of youth in this sample, many youth who participated gave shorter answers, and some youth did not participate, while parents spoke at length. Given that youth may have a different perspective on these experiences than parents, interviewing youth when they are older will be critical in further gauging youth’s reflections on the retransitioning process.

Additionally, this study may oversimplify the timeline of youth’s transitions, characterizing them as being more discrete than they actually are. For example, we asked participants to describe the age at which the child transitioned—operationalized as having changed pronouns—and thus people answered with a particular age (e.g., at age 8). However, we know anecdotally, as well as from empirical work (Kuper et al., 2019) that transitions often unfold over longer periods of time, in stages (e.g., wearing certain clothing and using certain pronouns at home, but not in public at first, and later branching out to other contexts), and the ordering of these stages differs greatly across children. Thus, we described transitions as happening at distinct ages with the goal of clarity, but this came at the cost of capturing some of the nuance associated with these transitions. For example, Table 2 presents youth’s moments of transition and retransition as being discrete points in time, implying that a given participant may have had two distinct changes in gender, when some youth may have experienced a consistently fluid sense of their identities and expressions but reported discrete ages to us due to the phrasing of our questions.

Of note, these data might not be generalizable to future generations of transgender youth. As culture and historical time period dictate what gender categories exist in society, as well as what levels of safety and acceptance people can expect when transitioning to those gender categories, the frequency with which people transition, and the genders to which they transition, may also change over time and across cultures. As an example, at the start of our longitudinal study, few people in the U.S. used the label “nonbinary” or used they/them pronouns, while doing so is more common today. That some of the youth in our study transitioned to nonbinary identities during this time period may be in part due to nonbinary identities and they/them pronouns becoming visible to them during the time period of their participation in the study, as some youth alluded to in their interviews.

Conclusions

The present study reports on a small subset of (initially) binary, socially transitioned transgender children who later retransitioned during their participation in a longitudinal study in North America. These findings provide evidence that when retransitions do occur, they do not invariably lead to social rejection and regret, as they have been feared to do. While regret undoubtedly can and does occur for some people who retransition (e.g., the famous case of Keira Bell), our data show that, in supportive environments, retransition can simply be another step of a longer gender trajectory. As demonstrated by several youth in our study who retransitioned more than once, the data in this paper present a single snapshot of time; likely, some of the youth described here, as well as others in the larger, longitudinal project will continue to refine and possibly relabel their identities. Future work with older children and teens, and those who experience less social support, are needed to better understand the diversity of youth’s experiences with retransitions after childhood social transitions. We hope the data presented here help clinicians and families to better understand and support youth who do retransition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rachel Horton, B.S., for assistance with data collection, as well as Daniel Alonso, B.A., Sam Choi, B.A., Deja Edwards, MPH, Jessica Garcila, B.S., Naomi Lee, B.S., Nikita Nerkar, B.S., Cally Nicholls, B.A., Kaitlyn Nickle, Sophia Robinson, B.A., and Iris Silan for assistance transcribing interviews. We also thank RL Goldberg, Ph.D., for providing feedback on the manuscript. Finally, the authors sincerely thank the families who participated in this study.

Because the latter group were living as binary transgender youth at the time of analysis, Olson et al. (2022) reports that 94% of youth are living as binary transgender youth approximately 5 years after initial social transition.

A chain mail message refers to a message that is meant to be circulated amongst a community.

See Olson et al. (2022) for more detailed report of the percentage of youth who retransitioned, including a breakdown by participants who have vs. have not participated recently (since 2019) and breakdown by other factors such as transition age and pubertal status.

Funding Statement

This work and/or author time was supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant SMA-1837857/SMA-2041463, and by the National Institutes of Health under Grant HD092347, all to Kristina Olson. This work was also supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (GRFP) grant to Lily Durwood, and by a National Science Foundation SBE Postdoctoral Research Fellowship (SPRF) to Ashley Jordan, award number 2105389.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Washington and Princeton University and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Data availability statement

Due to the sensitive nature of the study group, as well as the qualitative nature of the paper, the data reported in this paper are not publicly available.

References

- Ashley, F. (2019a). Gender (de)transitioning before puberty? A response to Steensma and Cohen-Kettenis (2011). Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(3), 679–680. 10.1007/s10508-018-1328-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley, F. (2019b). Thinking an ethics of gender exploration: Against delaying transition for transgender and gender creative youth. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 24(2), 223–236. 10.1177/1359104519836462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, E., Bockting, W., Botzer, M., Cohen-Kettenis, P., DeCuypere, G., Feldman, J., Fraser, L., Green, J., Knudson, G., Meyer, W. J., Monstrey, S., Adler, R. K., Brown, G. R., Devor, A. H., Ehrbar, R., Ettner, R., Eyler, E., Garofalo, R., Karasic, D. H., … Zucker, K. (2012). Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. International Journal of Transgenderism, 13(4), 165–232. 10.1080/15532739.2011.700873 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries, A. L. C., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2012). Clinical management of gender dysphoria in children and adolescents: The Dutch approach. Journal of Homosexuality, 59(3), 301–320. 10.1080/00918369.2012.653300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durwood, L., Eisner, L., Fladeboe, K., Ji, C., Barney, S., McLaughlin, K. A., & Olson, K. R. (2021). Social support and internalizing psychopathology in transgender youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(5), 841–854. 10.1007/s10964-020-01391-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards-Leeper, L., & Spack, N. P. (2012). Psychological evaluation and medical treatment of transgender youth in an interdisciplinary “gender management service” (GeMS) in a major pediatric center. Journal of Homosexuality, 59(3), 321–336. 10.1080/00918369.2012.653302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill-Peterson, J. (2018). Histories of the transgender child. University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Green, R. (2017). To transition or not to transition? That is the question. Current Sexual Health Reports, 9(2), 79–83. 10.1007/s11930-017-0106-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, A. H., D’Augelli, A. R., & Frank, J. A. (2011). Aspects of psychological resilience among transgender youth. Journal of LGBT Youth, 8(2), 103–115. 10.1080/19361653.2011.541347 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, A. H., D’Augelli, A. R., Howell, T. J., & Hubbard, S. (2005). Parent’ reactions to transgender youth’ gender nonconforming expression and identity. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 18(1), 3–16. 10.1300/J041v18n01_02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gülgöz, S., Glazier, J. J., Enright, E. A., Alonso, D. J., Durwood, L. J., Fast, A. A., Lowe, R., Ji, C., Heer, J., Martin, C. L., & Olson, K. R. (2019). Similarity in transgender and cisgender children’s gender development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116(49), 24480–24485. 10.1073/pnas.1909367116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, M. A., Ehrensaft, D., Tishelman, A. C., Clark, L. F., Garofalo, R., Rosenthal, S. M., Spack, N. P., & Olson, J. (2013). The gender affirmative model: What we know and what we aim to learn. Human Development, 56(5), 285–290. 10.1159/000355235 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand-Chupp, R. (2020). More than ‘canaries in the gender coal mine’: A transfeminist approach to research on detransition. The Sociological Review, 68(4), 800–816. 10.1177/0038026120934694 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuper, L. E., Lindley, L., & Lopez, X. (2019). Exploring the gender development histories of children and adolescents presenting for gender affirming medical care. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 7(3), 217–228. 10.1037/cpp0000290 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leibowitz, S. (2018). Social gender transition and the psychological interventions. In Janssen A. & Leibowitz S. (Eds.), Affirmative mental health care for transgender and gender diverse youth: A clinical guide. (pp. 31–47). Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-319-78307-9_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]