Background

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetic disorder that causes red blood cells to become misshapen and break down. Affecting 90,000 Black and Brown people in the US, the disease causes decreased blood flow resulting in pain, fatigue, and infection. SCD causes significant morbidity across the lifespan, affecting all aspects of patients’ daily functioning. Finding ways to manage the most common and debilitating complications, including chronic pain, is of utmost importance to restoring quality of life and decreasing health care utilization in this population. Several studies have estimated that chronic daily pain affects 30-50% of adult patients with SCD.1,2 Furthermore, in both pediatric and adult patients with SCD, those with more frequent chronic pain report more frequent depressive symptoms, more frequent hospital admission, and more significant functional disability.2,3 Those patients on chronic opioid therapy report poorer health-related quality of life (HRQL) outcomes as well as higher symptom burden and more somatic symptoms including depression and anxiety.4,5 Racism and stigma provide further barriers in the appropriate management of sickle cell disease.

Racial Disparities

Racial disparities in pain care appear to stem, in part, from a perceptual source. Previous psychological research in this domain has focused on high-level social cognitive processes. For example, volunteer adult participants, registered nurses, and nursing students attribute higher thresholds for pain to Blacks vs. Whites6,7 as a function of stereotypes regarding social status8 and false beliefs about racial biological differences.9 Beyond these factors, other work links reduced care for racial minorities’ pain to implicit racial bias10 and beliefs regarding substance abuse.11 Notably, studies of experimental pain suggest that Black participants exhibit lower pain tolerance and thresholds for pain12,13 stemming from cultural and neurobiological differences in pain beliefs, experiences, and coping.14 However, other work demonstrates a separate, potentially more tractable source of disparities in pain care: Biases in the visual perception of painful facial expressions. Specifically, White perceivers consistently demonstrate more conservative thresholds for seeing pain on Black (vs. White) faces.15 This perceptual bias stems from disruptions in configural processing: racial bias in pain perception was intact for upright faces, but significantly reduced when faces were inverted. Critically, racial bias in pain perception was still present when equating stimuli on skin tone, luminance, contrast, structure, and expression, and this bias in pain perception positively predicted racial bias in treatment independent of explicit prejudice and stereotypes. In sum, we suggest that disparities in pain care stem, in part, from a perceptual source. Disrupted configural processing of Black faces yields more stringent thresholds for the interpretation of perceived pain in Black patients, triggering a cascade of biased processing and behavior fueling societal-level racial inequity in care.

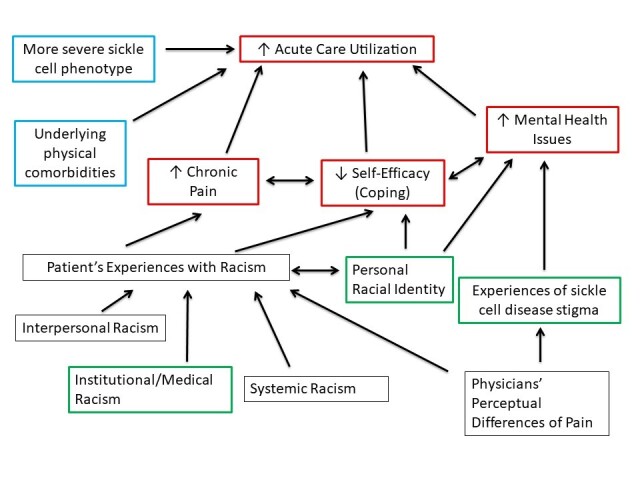

It is unclear how experiences of bias and discrimination affect health outcomes such as SCD pain. Discrimination is associated with decreased self-efficacy and poor mental health outcomes (see Figure 1). The Improving Patient Outcomes with Respect and Trust (IMPORT) study demonstrates that patients with SCD report higher rates of race-based discrimination compared to other Black patients.16 Disease-based discrimination was associated with more significant self-reported pain. Previous research has shown that patients with SCD report experiences of poorer interpersonal care when hospitalized than other patient groups (9). Furthermore, these patients report poor communication with medical personnel, which has been associated with lower trust and higher rates of discharge against medical advice (10). Because virtually all patients with SCD identify as Black or other racial and ethnic minorities, it is important to understand how experiences of racism and stigma interact to affect a patient’s health and functioning. It is unclear how physical, psychosocial, and other drivers influence pain, self-efficacy at managing SCD and care utilization in patients with SCD and chronic pain.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of Chronic Pain Drivers in Sickle Cell Disease. Red boxes: outcomes of interest; Blue boxes: physical drivers; Green boxes: psychosocial drivers; Black boxes: additional drivers.

The IMPORT Study

The IMPORT study demonstrated important relationships between experiences of SCD-related stigma and increased acute care utilization.6 The IMPORT study was an NHLBI-funded observational cohort study of SCD patient experiences with health care. Participants were recruited at two academic medical centers in the Baltimore/Washington, DC Metro area. To be eligible for participation, clinic attendees needed to be over 15 years of age, with HbSS, HbSC, Hb SB-thalassemia, or Hb SS/α-thalassemia and no plans to move within three years. Participants completed a battery of surveys including the Self-Care Self-Efficacy Scale (SCSES) upon enrollment and every six months across three years. A total of 291 subjects were enrolled. Dr. Lanzkron is a co-investigator on this project and maintains IRB approval for the study at Johns Hopkins (IRB00234974). Patients with SCD report greater burden of disease-based discrimination that is associated with higher self-reported pain measures.7,16 Racism can be experienced at many levels; health care settings are certainly not immune and have been sources of some of the most egregious examples in our history. Since SCD is predominantly seen in Black patients, experiences of racism are a key contributor to their health.12–14

Experiences of Racism

Experiences of racism have negative effects on chronic pain and depressive symptoms in SCD. Previous research noted that higher levels of perceived racism predicted more depressive symptoms in adolescents with SCD.15 An additional study found that in adolescent patients with SCD, greater experiences of racism were associated with greater pain burden and greater perceived health-related stigma was associated with lower health-related quality of life.17 Although a systematic review demonstrated an association between pain and depressive or anxiety symptoms in pediatric SCD, they noted the need for ongoing research to better understand the relationship and to extend the research to adult patients.18 Furthermore, ways to intervene to moderate these effects have not yet been studied.

Self-Management Programs

Self-management programs may be efficacious for treatment of chronic pain. Though not yet tested for patients with SCD, peer-led self-management groups as an alternative to those facilitated by experts have been trialed in other patient populations with positive results. For example, in other chronic diseases such as diabetes and HIV, self-management programs have been shown to improve health outcomes and patient self-efficacy.5,8 Research has shown feasibility and effectiveness in pain management for elderly nursing home patients and women living with HIV/AIDS.9,10 In these studies, there was a significant reduction in daily pain scores as well as an improvement in patient-reported mood measures; sample sizes were small and did not include SCD patients. Our preliminary data also showed that most respondents felt that peers or people living with SCD should be involved in leading the groups. This finding reinforces the importance of using a community-engaged research (CEnR) approach to developing such a programmatic intervention. Additionally, mental health literature demonstrates that group interventions can be used to decrease disease-specific stigma; this has not yet been studied in SCD.19

Sickle Cell Programs in Delaware

ChristianaCare’s Sickle Cell Program cares for almost half of the 400 adult patients with SCD who reside in Delaware. In a pilot funded by the Delaware Center for Translational Research ACCEL program, we are adapting the general curriculum of a peer-mediated pain group specifically for use in SCD using key informant interviews with patients with SCD and family members. The general six-week curriculum for a peer mediated group intervention helps patients with a range of chronic illnesses decrease pain levels and develop coping skills. Patient-reported outcomes are measured and monitored via PROMIS-29 scale at the beginning and end of the program, as well as through the Global Impression Scale at the end and the PHQ9 and GAD7, measures of depression and anxiety, throughout. This program provides a supportive platform for patients to share their narrative and struggles. During individual meetings prior to group sessions, the patient and physician identify challenges and begin to work on solving problems. The course teaches skills that help manage pain through relaxation, visualization, and guided imagery exercises. Participants set realistic goals that are congruent with their morals and values and create a paced, modified, or replacement approach to accomplish those goals. Adding the perspective and curricular items important to those patients with SCD, specifically addressing racism and stigma, we hypothesize will enhance the effectiveness of the intervention.

The next steps in this work are funded through a COBRE grant supporting the Delaware Comprehensive Sickle Cell Research Network of which ChristianaCare is a member. We plan to examine the complex interplay between experiences of racism at many levels, disease-related stigma, and racial identity on chronic pain. First, we will analyze the landmark IMPORT dataset to evaluate the relationship between SCD-related stigma and self-efficacy in the management of SCD. Next, we will explore the themes of racism in a medical setting, SCD-related stigma, and self-efficacy in disease management in order to incorporate them into the curriculum. Finally, we will demonstrate feasibility of the SCD-specific chronic pain curriculum we have created through extensive community engagement. While group interventions have demonstrated effectiveness in improving outcomes for other chronic diseases, they have not yet been studied in SCD. The use of peer-mediators is also novel in SCD. Once these relationships are better understood and the curriculum has been proven feasible, we can pilot the intervention and evaluate its impact on the experience of chronic pain and effective self-management of disease in adult patients with SCD.

Innovation

Previous research has begun to evaluate the relationship between experiences of racism, stigma, and chronic pain in SCD, yet significant gaps in our understanding of these interactions remain. Furthermore, the way that patients’ self- perception of race influences these experiences is also unclear. As the mental health literature demonstrates, one way to effectively fight stigma is through group interventions.

This evaluation of the IMPORT dataset will be the first analysis of the associations between experiences of stigma and self-efficacy at managing SCD. These data were collected from a large group of adult patients with SCD in a longitudinal cohort at two major institutions and demonstrate important interactions between SCD-related stigma, worsening pain, trust, and communication in healthcare.6 This innovative study was the first to specifically examine these factors in SCD and demonstrated a greater burden of race-based discrimination than was previously reported in other Black cohorts, indicating the unique barriers faced by patients with SCD. Additionally, the study validated a SCD-specific tool to evaluate stigma and collected data on ratings of self-efficacy. However, the relationship between these two factors has not yet been explored.

This project will be the first to look at how racial identity relates to experiences of stigma and discrimination and ratings of self-efficacy at managing SCD. The interaction between these factors have not been explored, particularly through a qualitative methodology. An improved understanding of these relationships, particularly in adult patients with SCD, will better inform our intervention to address the drivers of chronic pain and acute care utilization. Patients with SCD may experience both race-based discrimination and SCD-related stigma, both of which are influenced by a patient’s own racial identity. This will be the first peer-mediated intervention that specifically targets chronic pain in SCD. Group programs have documented efficacy in general chronic pain management, but this will be the first study to examine peer-led groups to improve self-efficacy in SCD. Ultimately, having an effective non-pharmacologic approach to chronic pain would be a ground-breaking intervention that addresses an outcome that patients have expressed is important to them. The intervention will be developed based on specific needs identified by the community of patients with SCD. Any treatment modality must address not only the physical manifestations and chronic pain, but also the patients’ psychosocial experiences of racism and stigma. Our proposed project is driven by strong interest from our patients with SCD based on preliminary data. We will build on the work accomplished during the first year of our CTR Pilot Project into this COBRE2 target project, to adapt the current chronic pain curriculum for use in SCD. The intervention will be led by peer leaders with SCD in collaboration with clinicians, representing a paradigm-shift in the approach to patient education and care delivery. By involving patients with SCD in community-engaged research to evaluate and adapt materials, the curriculum and peer leaders produced by this project will be unique. We will be the first research group to create an intervention that addresses how bias and discrimination affect health outcomes in SCD pain, led by the very patients who experience it. The relationship of these drivers, especially as they relate to chronic pain in SCD, will give patients a nonpharmacological treatment option and a new approach to hopeful self-care.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 5P20GM109022-07. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Smith, W. R., Penberthy, L. T., Bovbjerg, V. E., McClish, D. K., Roberts, J. D., Dahman, B., et al. Roseff, S. D. (2008, January 15). Daily assessment of pain in adults with sickle cell disease. Annals of Internal Medicine, 148(2), 94–101. 10.7326/0003-4819-148-2-200801150-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sil, S., Cohen, L. L., & Dampier, C. (2016, June). Psychosocial and functional outcomes in youth with chronic sickle cell pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 32(6), 527–533. 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee, S., Vania, D. K., Bhor, M., Revicki, D., Abogunrin, S., & Sarri, G. (2020, July 7). Patient-reported outcomes and economic burden of adults with sickle cell disease in the United States: A systematic review. International Journal of General Medicine, 13, 361–377. 10.2147/IJGM.S257340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adam, S. S., Telen, M. J., Jonassaint, C. R., de Castro, L. M., & Jonassaint, J. C. (2010, July). The relationship of opioid analgesia to quality of life in an adult sickle cell population. Health Outcomes Research in Medicine, 1(1), e29–e37. 10.1016/j.ehrm.2010.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sogutlu, A., Levenson, J. L., McClish, D. K., Rosef, S. D., & Smith, W. R. (2011, May-June). Somatic symptom burden in adults with sickle cell disease predicts pain, depression, anxiety, health care utilization, and quality of life: The PiSCES project. Psychosomatics, 52(3), 272–279. 10.1016/j.psym.2011.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bediako, S. M., Lanzkron, S., Diener-West, M., Onojobi, G., Beach, M. C., & Haywood, C., Jr. (2016, May). The measure of sickle cell stigma: Initial findings from the Improving Patient Outcomes through Respect and Trust study. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(5), 808–820. 10.1177/1359105314539530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haywood, C., Jr., Lanzkron, S., Bediako, S., Strouse, J. J., Haythornthwaite, J., Carroll, C. P., . . .. Beach, M. C., & the IMPORT Investigators. (2014, December). Perceived discrimination, patient trust, and adherence to medical recommendations among persons with sickle cell disease. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 29(12), 1657–1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Trawalter, S., Hoffman, K. M., & Waytz, A. (2012). Racial bias in perceptions of others’ pain. PLoS One, 7(11), e48546. 10.1371/journal.pone.0048546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffman, K. M., Trawalter, S., Axt, J. R., & Oliver, M. N. (2016, April 19). Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(16), 4296–4301. 10.1073/pnas.1516047113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sabin, J. A., & Greenwald, A. G. (2012, May). The influence of implicit bias on treatment recommendations for 4 common pediatric conditions: Pain, urinary tract infection, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and asthma. American Journal of Public Health, 102(5), 988–995. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hausmann, L. R. M., Gao, S., Lee, E. S., & Kwoh, K. C. (2013, January). Racial disparities in the monitoring of patients on chronic opioid therapy. Pain, 154(1), 46–52. 10.1016/j.pain.2012.07.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bailey, Z. D., Krieger, N., Agénor, M., Graves, J., Linos, N., & Bassett, M. T. (2017, April 8). Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet, 389(10077), 1453–1463. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trent, M., Dooley, D. G., Dougé, J., Cavanaugh, R. M., Lacroix, A. E., Fanburg, J., . . .. Wallace, S. B., & the SECTION ON ADOLESCENT HEALTH, & the COUNCIL ON COMMUNITY PEDIATRICS, & the COMMITTEE ON ADOLESCENCE. (2019, August). The impact of racism on child and adolescent health. Pediatrics, 144(2), e20191765. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Power-Hays, A., & McGann, P. T. (2020, November 12). When actions speak louder than words – racism and sickle cell disease. The New England Journal of Medicine, 383(20), 1902–1903. 10.1056/NEJMp2022125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mougianis, I., Cohen, L. L., Martin, S., Shneider, C., & Bishop, M. (2020, September 1). Racism and health-related quality of life in pediatric sickle cell disease: Roles of depression and support. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 45(8), 858–866. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haywood, C., Jr., Diener-West, M., Strouse, J., Carroll, C. P., Bediako, S., Lanzkron, S., . . .. Beach, M. C., & the IMPORT Investigators, & the IMPORT Investigators. (2014, November). Perceived discrimination in health care is associated with a greater burden of pain in sickle cell disease. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 48(5), 934–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Wakefield, E. O., Popp, J. M., Dale, L. P., Santanelli, J. P., Pantaleao, A., & Zempsky, W. T. (2017, February/March). Perceived racial bias and health-related stigma among youth with sickle cell disease. J Dev Behav Pediatr, 38(2), 129–134. 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reader, S. K., Rockman, L. M., Okonak, K. M., Ruppe, N. M., Keeler, C. N., & Kazak, A. E. (2020, June). Systematic review: Pain and emotional functioning in pediatric sickle cell disease. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 27(2), 343–365. 10.1007/s10880-019-09647-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schomerus, G., Angermeyer, M. C., Baumeister, S. E., Stolzenburg, S., Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2016, February). An online intervention using information on the mental health-mental illness continuum to reduce stigma. Eur Psychiatry, 32, 21–27. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]