Summary

Background

There are concerns that suicidal behaviors are arising among adolescents. The COVID-19 pandemic could have worsened the picture, however, studies on this topic reported contrasting results. This work aimed to summarise findings from the worldwide emerging literature on the rates of suicidality among young people during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis were performed, searching five electronic databases for studies published from January 1, 2020 until July 27, 2022. Studies reporting rates for each of the three considered outcomes (suicide, suicidal behaviors, and suicidal ideation) among young people under 19 years old during the COVID-19 pandemic were included. Random-effects meta-analyses were conducted, and the intra-study risk of bias was assessed. When pre-COVID-19 data were available, incidence rate ratio (IRR) and prevalence ratio (PR) estimates were calculated between the two periods. All the analyses were performed according to the setting explored: general population, emergency department (ED), and psychiatric services. The review protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42022308014).

Findings

Forty-seven observational studies were selected for more than 65 million subjects. The results of the meta-analysis showed a pooled annual incidence rate of suicides of 4.9 cases/100,000 during 2020, accounting for a non-statistically significant increase of 10% compared to 2019 (IRR 1.10, 95% CI: 0.94–1.29). The suicidal behaviors pooled prevalence during the COVID-19 pandemic was higher in the psychiatric setting (25%; 95% CI: 17–36%) than in the general population (3%; 1–13%) and ED (1%; 0–9%). The pooled rate of suicidal ideation was 17% in the general population (11–25%), 36% in psychiatric setting (20–56%) and 2% in ED (0–12%). The heterogeneity level was over 97% for both outcomes in all settings considered. The comparison between before and during COVID-19 periods highlighted a non-statistically significant upward trend in suicidal behaviors among the general population and in ED setting. The only significant increase was found for suicidal ideation in psychiatric setting among studies conducted in 2021 (PR 1.15; 95% CI: 1.04–1.27), not observed exploring 2020 alone.

Interpretation

During the pandemic, suicide spectrum issues seemed to follow the known pattern described in previous studies, with higher rates of suicidal ideation than of suicidal behaviors and suicide events. Governments and other stakeholders should be mindful that youth may have unique risks at the outset of large disasters like the COVID-19 pandemic and proactive steps are necessary to address the needs of youth to mitigate those risks.

Funding

The present study was funded by the University of Torino (CHAL_RILO_21_01).

Keywords: Child and adolescent, Mental health, Meta-analysis, Suicide, COVID-19

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

The suicide spectrum represents an important worldwide issue, and suicide itself is the fourth leading cause of death among 15–19 years old. There are concerns that suicidal behaviors are arising among adolescents during the last decade, and some studies have pointed out that this issue is still largely hidden in the community as if it was the submerged portion of an iceberg. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic could have worsened the situation, increasing the psychological discomfort of young people. We searched five international databases between January 1, 2020 and July 27, 2022 for studies on the prevalence of suicide spectrum issues among young people during the COVID-19 pandemic using the keywords “suicide”, “suicidal behaviors”, and “suicidal ideation”. We identified 2530 studies from the search strategy, of which 47 were relevant to our review and meta-analysis. The intra-study risk of bias assessment showed an overall good quality of the selected studies. Although we found previous systematic reviews that explored this phenomenon, we did not identify any meta-analyses evaluating the proportion of people who develop suicide spectrum issues after COVID-19 outbreak.

Added value of this study

Our meta-analysis was conducted to describe the rates of suicide, suicidal behaviors, and suicidal ideation among young people under 19 years old during the COVID-19 pandemic. If possible, the phenomenon of suicidality has been compared between pre- and during the COVID-19 pandemic periods. Our results confirm the pyramidal structure of the phenomenon, with higher rates of suicidal ideation than suicidal behaviors. However, it was also highlighted how the setting explored led to considerably different rates: overall, in the general population, the phenomena are less frequent, while their rates are gradually higher in the emergency department and mental health settings. Comparing the periods pre- and during the COVID-19, pooled rates are similar for all suicidal measures and showed stability over time in all the examined settings. In particular, suicidal behaviors showed an increasing, but not significant trend in the general population and in emergency department settings, while studies conducted at a greater temporal distance from the pandemic outbreak (2020–2021) reported a statistically significant escalation in the suicidal ideation in the psychiatric setting, not seen when exploring the 2020 alone.

Implications of all the available evidence

The results obtained agree with those reported in the previous literature on the topic. During COVID-19 pandemic, the suicidal behaviors showed an increase, and, in particular, a sharp growing trend could be observed starting from Summer 2020. These findings might be of interest from a public health perspective. Governments and other stakeholders should be mindful that youth may have unique risks at the outset of large disasters like the COVID-19 pandemic and proactive steps are necessary to address the needs of youth to mitigate those risks.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, more than 700,000 people die by suicide every year, accounting for one person every 40 seconds.1 The most affected age group seems to be young people from 15 to 30 years old. In particular, adolescence was highlighted as a period of imbalance between a heightened sensitivity to motivational cues and immature cognitive control.2, 3, 4, 5 Such neurodevelopmental vulnerability could put adolescents at higher risk of impulsive suicidal behaviors as a dysfunctional response to moments of crisis.2, 3, 4, 5 In 2019, suicide was globally the fourth leading cause of death among 15–19 years old, after road injury, tuberculosis, and interpersonal violence.1

Overall, more than 20 suicide attempts occur for each suicide.1 This phenomenon is well represented by the Van Heeringen's pyramid of suicide: among young people, as well as in adults, suicidal symptomatology can be seen as a continuum from suicidal thoughts, at the bottom of the pyramid, to suicidal behaviors and suicide, placed at the top.6,7 Suicidal thoughts are considered the initial phase of this continuum, but not everyone who reports suicidal thoughts/ideation subsequently develops a suicidal behavior.6, 7, 8, 9

Hawton and colleagues stated that only a small proportion of adolescents with suicidal behaviors presents to the clinical services, meaning that this issue is still largely hidden in the community as if it was the submerged portion of an iceberg.4,10 Furthermore, also in emergency departments, suicidal thoughts are often under-documented, meaning that suicidal symptomatology is not always recognized, and therefore patients miss the opportunity of being addressed towards mental health services.11,12

The prevalence of psychological symptoms and suicide behaviors has significantly increased in young people during the last decade, becoming an important public health matter.13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 Moreover, in the last period, changes and restrictions in youths' lives caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, including school closures, may have both positive and negative effects on the adolescents' mental health and suicidality.20,21

On the one hand, several aspects such as limited access to schools and medical services, restricted social interactions and leisure activities, and – in some cases – family economic hardship could have led to increased conflicts and intrafamilial violence episodes, and reduced opportunities for stress regulation. All these factors could raise anxiety and depression among adolescents.20,22, 23, 24, 25, 26 On the other hand, the great amount of time spent at home could have promoted the development of stronger intrafamilial cohesion by spending more time together.20 Moreover, school closures could have reduced the distress related to academic burden and peer problems.20,21 Together, these positive elements could have contained adolescents' anxiety and depressive symptoms, at least in the early phases of pandemic, and might have controlled the potentially high risk of suicide.20,27, 28, 29

Globally, in the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, increasing rates were registered for several mental conditions (depressive and anxiety symptoms, restrictive eating disorders, attitude problems) compared to pre-pandemic levels.30 Although these conditions were strongly associated with suicidal attempts,31 suicide rates did not seem to change significantly.32 However, a more recent study suggests a potential variation of the phenomenon in different countries,23 and the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the Children's Hospital Association have recently declared that the pandemic-related decline in youth's mental health has become a national emergency.33 Furthermore, as a result of the protracted pandemic, several authors underlined the need for a renewed consideration of youth suicide after the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.12,20,29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36

The aim of this review and meta-analysis is to assess and summarize findings from emerging literature on worldwide rates of suicide, suicidal behaviors, and suicidal ideation among young people under 19 years old. The secondary purpose is to compare the phenomenon of suicidality between pre- and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

This review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.37 The study protocol is available online on PROSPERO (CRD42022308014). We included quantitative studies that reported summary rates of suicide, suicidal behaviors, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic among under 19-year-old people. All types of studies were considered, including cross-sectional and cohort studies. Studies that met the inclusion criteria but did not report useful data for the meta-analysis were included in the narrative synthesis.

Five electronic databases (PubMed, Embase, Scopus, CINAHL, and Web of Science) were systematically searched for studies published in English from January 1, 2020 until July 27, 2022. We used a combination of the following terms for the database search: “suicide”, “suicidal ideation”, “adolescents”, “children”, “covid-19”, and “sars-cov-2”. A backward reference search of included studies and any relevant reviews supplemented our search strategy. Full search strategies are available in the Supplementary file 1, Table A1.

The screening of studies, data collection, and risk of bias assessment were done independently by MB, EK, and RIC; disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Data analysis

Data were collected using a standardised data extraction form. Extracted data included the name of the first author, year of publication, geographical location of the study, number of suicides, suicidal ideation and/or suicidal behaviors cases, the size of the population observed, study setting, and period of observation. When the estimate of interest was not explicitly reported, we used the raw figures available to compute it, or we asked the authors for more precise data.

The primary outcomes were the rates of suicide, suicidal behaviors, and suicidal ideation, considered separately, among young people during COVID-19 pandemic. Suicidal behaviors and suicidal ideation were explored according to the study setting: the general population, the population of individuals who accessed an Emergency Department (ED) for any causes, and those assessed for mental conditions (psychiatric setting). The secondary outcome was the comparison of the primary outcome, where possible, with the same phenomenon before the pandemic.

Random effects meta-analysis using generalised linear mixed model (GLMM) was performed to pool proportions.38 Both 95% confidence intervals (CI), with Clopper-Pearson method to stabilise the variance, and 95% prediction intervals were estimated.39 For studies that reported outcome rates in both pre- and during-pandemic periods, we computed the incidence rate ratio (IRR) and the prevalence ratio (PR) using the pre-pandemic period as reference. Pooled IRRs and PRs were calculated using the inverse variance method. The heterogeneity between study-specific estimates was measured with the I2 statistics.40 Statistical significance was established for outcomes with a p-value <0.05.

To explore whether the country or the geographical area could be associated with suicide, suicide behaviors, or suicide ideation, a random-effects meta-regression was used to quantify variables that had a positive or negative relationship with the outcomes. A second meta-regression has been performed in order to assess the effect of the recall bias (a systematic error that occurs when subjects do not remember previous events or experiences accurately) on the outcome explored. A sub-group analysis has been performed to assess the effect of the time-period explored by each study (only 2020, only 2021, or both years 2020–2021). Sensitivity analyses were performed identifying outliers and using the leave-one-out technique to control the between-study heterogeneity.41 A sensitivity analysis excluding studies with high risks of bias (JBI score < 7) has also been performed to assess the impact of intra-study risk of bias. The analyses were performed using the statistical program R (version 4.1.1)42 with metafor and meta packages.43

A systematic narrative synthesis was performed to present available data for all studies that could not be included in the meta-analysis.

As the analysis was primarily conducted with proportion-based meta-analysis, publication bias was not assessed with the lack of a suitable tool in single-arm meta-analysis to assess publication bias and a small quantity of included studies.44 The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Prevalence Critical Appraisal tool was used to evaluate the methodological quality of the included studies.45 Two authors of the present study (MB and EK) independently conducted the assessment of the risk of bias. Disagreements were solved first by discussion, and then by consulting a third reviewer (RIC), if disagreements persisted.

Role of the funding source

The present study was funded by the University of Torino (CHAL_RILO_21_01). The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Results

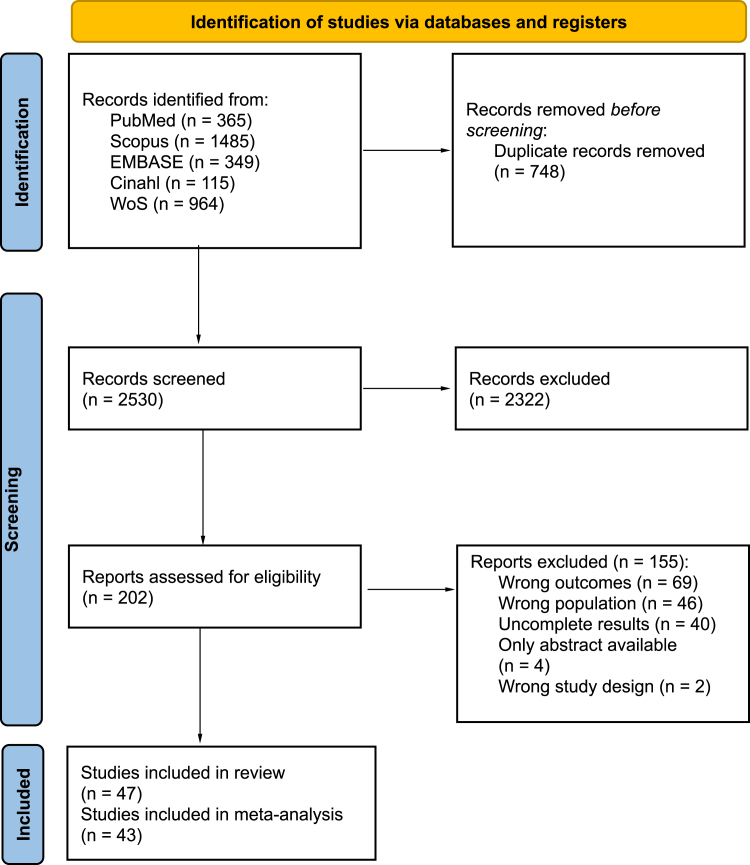

The systematic database search retrieved 2530 records that were screened. Among these, 202 studies underwent full-text evaluation. After excluding 155 studies for the reasons outlined in Fig. 1, 47 studies were included in the systematic review (study characteristics are reported in Table 1).32,46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91 Among these studies, 43 were included in the meta-analytical process, for a total of around 65 million subjects (suicides: 63,120,235; suicidal behaviors: 934,951; suicidal ideation: 156,234): two reporting rates of deaths for suicides,48,50 26 reporting prevalence data about suicidal behaviors51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76 and 35 reporting prevalence data about suicidal ideation.51,53,54,56,60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73,75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91 Four studies reporting suicide rates data32,46,47,49 were excluded from the meta-analytic process and included only in a narrative synthesis, due to design-related issues. In the Supplementary file 1, Fig. A1 represents the geographical distribution of the eligible studies related to suicidal behaviors and suicidal ideation, while the studies about suicide were conducted in only two countries, Japan and USA. Definitions of the three outcomes and codes/tools used for their identification are summarised in the Supplementary file 1, Table A2. The periods of time explored by each study included in the review and meta-analysis, according to the outcome considered, are summarised in the Supplementary file 1, Table A3. The intra-study risk of bias is also provided in the Supplementary file 1, Table A4. Forty-one studies out of 47 (87%) were of good quality, identified by a JBI score ≥7.

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram of the observational studies selection process.

Table 1.

Studies included in the review and meta-analysis by outcome.

| Study | Country | Study design | Age range | Setting | Outcome measure | Sample size | Cases | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A. Studies reporting death by suicide | ||||||||

| Anzai T, 202046 | Japan | Observational | <19 | General population | Number of suicides from March to May | 2019: 21,192,500 2020: 20,872,500 |

2019: 212 2020: 197 |

Male: excess mortality was observed in May (0.6) and June (3.7). Female: excess mortality was observed in March (5.3) and June (12.6) |

| Charpignon ML, 202250 | USA | Observational | 10–19 | General population | Annual number of suicides | 2019: 41,852,838 2020: 41,715,352 |

2019: 2755 2020: 2806 |

|

| Ehlman DC, 202249 | USA | Observational | 10–14 | General population | Annual number of suicides | 2019: 20,538,461 2020: 20,750,000 |

2019: 534 2020: 581 |

|

| Isumi A, 202032 | Japan | Observational | <19 | General population | IRR comparing the number of events from March to May in 2020 and in 2018–2019 | NA | NA | The event rate significantly increased in May (IRR: 1.34, 95% CI 1.01–1.78) compared to March |

| Matsumoto R, 202148 | Japan | Observational | <19 | General population | Annual number of suicides (first 6 months of 2021) | 2019: 21,691,777 2020: 21,404,883 2021: 21,037,601 |

2019: 21,691,777 2020: 21,404,883 2021: 404 |

|

| Tanaka T, 202147 | Japan | Observational | <19 | General population | Number of suicides February–June and July–October | Feb–Jun 2019: Jul–Oct 2019: Feb–Jun 2020: Jul–Oct 2020: |

Feb–Jun 2019: Jul–Oct 2019: Feb–Jun 2020: Jul–Oct 2020: |

IRR first wave (February–June): 0.98, 95% CI: 0.75–1.27 IRR second wave (July–October): 1.49, 95% CI: 1.12–1.98 |

| Panel B. Studies reporting prevalence data of suicidal behaviors | ||||||||

| Bukuluki P, 202151 | Uganda | Cross-sectional | 13–19 | General population | Prevalence within the past 6 months (structured interview in August 2020) | 219 | 53 | The prevalence within the past 6 months preceding the survey was 24.2% (95% CI: 18.7–30.4) |

| Carison A, 202152 | Australia | Observational | 7–18 | ED | Prevalence (time-period: April–September) | 2019: 18,935 2020: 11,235 |

2019: 313 2020: 515 |

|

| Psychiatric setting | 2019: 809 2020: 1190 |

2019: 313 2020: 515 |

||||||

| Díaz de Neira M, 202153 | Spain | Cross-sectional | 0–17 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: 11th March–11th April) | 2019: 95 2020: 43 |

2019: 15 2020: 10 |

|

| Ferrando SJ, 202154 | USA | Observational | NA | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: January–February 2020 , March–April 2020) | Jan–Feb: 202 Mar–Apr: 65 |

Jan–Feb: 36 Mar–Apr: 13 |

|

| Fidancı I, 202155 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | 0–18 | ED | Prevalence (time-period: April–October) | 2019: 55,678 2020: 19,061 |

2019: 187 2020: 31 |

|

| Gatta M, 202256 | Italy | Observational | 0–17 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: February–March) | 2019–2020: 102 2020–2021: 96 |

2019–2020: 25 2020–2021: 18 |

|

| Gorny M, 202157 | UK | Observational | 0–18 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: March–May 2020) | 39 | 17 | |

| Gracia R, 202158 | Spain | Observational | 12–18 | General population | Prevalence (time-period: March–March) | 2019: 835,030 2020: 835,430 |

2019: 552 2020: 690 |

|

| Habu H, 202159 | Japan | Observational | NA | ED | Prevalence (time-period: March–August) | 2019: 1136 2020: 685 |

2019: 1 2020: 2 |

|

| Hou T, 202060 | China | Cross-sectional | Senior high school students | General population | Prevalence within the past 2 weeks (structured interview) | 859 | 64 | |

| Hou T, 202161 | China | Cross-sectional | 15–17 | General population | Prevalence within the past 2 weeks (structured interview in August 2020) | 761 | 79 | |

| Ibeziako P, 202262 | USA | Observational | 4–18 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: March 2019–February 2020, March 2020–February 2021) | 2019–2020: 2020 2020–2021: 1799 |

2019–2020: 236 2020–2021: 369 |

|

| Jones SA, 202263 | USA | Cross-sectional | 14–18 | General population | Prevalence within the past 12 months (January–June 2021) | 7705 | 693 | |

| Kirič B, 202264 | Slovenia | Observational | 6–19 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: March 2019–February 2020, March 2020–July 2021) | 2019–2020: 784 2020–2021: 1191 |

2019–2020: 67 2020–2021: 160 |

|

| Koenig J, 202165 | Germany | Observational | 12–18 | General population | Prevalence within the past 2 weeks (structured interview, before and after March 2020, matching subjects in the two periods on age, sex and type of school) | Before March 2020: 324 March–August 2020: 324 |

Before March 2020: 1 March–August 2020: 1 |

|

| Kose S, 202166 | Turkey | Observational | <18 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: 11th March–11th June 2019, 11th March–11th June 2020) | 2019: 128 2020: 66 |

2019: 31 2020: 14 |

|

| Llorca-Bofí V, 202267 | Spain | Observational | <18 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: January–March 2020, March–June 2020, October 2020–May 2021) | Jan–Mar 2020: 46 Mar–Jun 2020: 51 Oct 2020–May 2021: 245 |

Mar–Jun 2020: 9 Mar–Jun 2020: 6 Oct 2020–May 2021: 31 |

|

| McLoughlin A, 202268 | Ireland | Observational | <18 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: March–May) | 2019: 15 2020: 23 2021: 47 |

2019: 8 2020: 9 2021: 24 |

|

| Miles J, 202169 | USA | Observational | 2–18 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: January–December 2019, January–December 2020) | 2019: 1380 2020: 1380 |

2019: 538 2020: 239 |

|

| Millner AJ, 202270 | USA | Observational | 12–19 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence within the past month (time-period: March 2017–March 2020, March 2020–March 2021) | 2017–2020: 1096 2020–2021: 275 |

2017–2020: 318 2020–2021: 139 |

|

| Mohd Fadhli SA, 202271 | Malaysia | Cross-sectional | 13–17 | General population | Prevalence within the past 12 months (online survey, time-period: May–September 2021) | 1290 | 108 | |

| Murata S, 202172 | USA | Cross-sectional | 13–18 | General population | Prevalence (online survey, time-period: April–July 2020) | 583 | 8 | |

| Ridout KK, 202173 | USA | Cross-sectional | 5–17 | ED | Prevalence (time-period: 10th March–15th December 2019, 10th March–15th December 2020) | 2019: 104,293 2020: 48,207 |

2019: 699 2020: 868 |

|

| Rømer TB, 202174 | Denmark | Observational | 0–17 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: January–December 2019, January 2020–February 2021) | 2019: 768 2020: 1133 |

2019: 295 2020: 406 |

|

| Sevecke K, 202275 | Germany | Observational | 6–18 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: January–December 2020, January–December 2021) | 2020: 383 2021: 538 |

2020: 112 2021: 158 |

|

| Zhang L, 202076 | China | Longitudinal cohort study | 9–16 | General population | Prevalence within the past 3 months (structured questionnaire in November 2019 and in May 2020) | 2019: 1271 2020: 1241 |

2019: 38 2020: 79 |

|

| Panel C. Studies reporting prevalence data of suicidal ideation | ||||||||

| Berger G, 202277 | Switzerland | Observational | <18 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time period: March–April) | 2019: 109 2020: 86 2021: 164 |

2019: 74 2020: 62 2021: 137 |

|

| Bukuluki P, 202151 | Uganda | Cross-sectional | 13–19 | General population | Prevalence within the past 4 months (structured interview in August 2020) | 219 | 67 | |

| Cai H, 202278 | China | Cross-sectional | 10–19 | General population | Prevalence (online survey, study period: August 2020–March 2021) | 1057 | 125 | |

| Chadi N, 202179 | Canada | Observational | 12–17 | ED | Prevalence (time-period: January–December) | 2018–2019: 24,824 2020: 18,988 |

2018–2019: 1180 2020: 1073 |

|

| Psychiatric setting | 2018–2019: 2355 2020: 2201 |

2018–2019: 1180 2020: 1073 |

||||||

| Cordeiro F, 202180 | Portugal | Observational | NA | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: March–June) | 2019: 178 2020: 59 |

2019: 31 2020: 10 |

|

| Davico C, 202181 | Italy | Observational | <18 | ED | Prevalence (time-period: 7 weeks before–8 weeks after lockdown (24th February 2020)) | Before 24th Feb: 10,888 After 24th Feb: 3395 |

Before 24th Feb: 18 After 24th Feb: 9 |

|

| Psychiatric setting | Before 24th Feb: 93 After 24th Feb: 50 |

Before 24th Feb: 18 After 24th Feb: 9 |

||||||

| Díaz de Neira M, 202153 | Spain | Cross-sectional | 0–17 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: 11th March–11th April) | 2019: 95 2020: 43 |

2019: 31 2020: 24 |

|

| Ferrando SJ, 202154 | USA | Observational | NA | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: January–February 2020, March–April 2020) | Jan–Feb: 202 Mar–Apr: 65 |

Jan–Feb: 93 Mar–Apr: 28 |

|

| Fogarty A, 202282 | Australia | Cross-sectional | 14–17 | General population | Prevalence within the past 2 weeks (online survey, time period: June–September 2020) | 257 | 54 | |

| Gatta M, 202256 | Italy | Observational | 0–17 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: February–March) | 2019–2020: 102 2020–2021: 96 |

2019–2020: 46 2020–2021: 52 |

|

| Hou T, 202060 | China | Cross-sectional | 15–17 | General population | Prevalence within the past 2 weeks (structured interview) | 859 | 269 | |

| Hou T, 202161 | China | Cross-sectional | 15–17 | General population | Prevalence within the past 2 weeks (structured interview in August 2020) | 761 | 277 | |

| Ibeziako P, 202262 | USA | Observational | 4–18 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: March 2019–February 2020, March 2020–February 2021) | 2019–2020: 2020 2020–2021: 1799 |

2019–2020: 1004 2020–2021: 1073 |

|

| Jones SE, 202263 | USA | Cross-sectional | 14–18 | General population | Prevalence within the past 12 months (January–June 2021) | 7705 | 1533 | |

| Kiric B, 202264 | Slovenia | Observational | 6–19 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: March 2019–February 2020, March 2020–July 2021) | 2019–2020: 784 2020–2021: 1191 |

2019–2020: 307 2020–2021: 537 |

|

| Koenig J, 202165 | Germany | Observational | 12–18 | General population | Prevalence within the past 2 weeks (structured interview, before and after March 2020, matching subjects in the two periods on age, sex and type of school) | Before March 2020: 324 March–August 2020: 324 |

Before March 2020: 44 March–August 2020: 33 |

|

| Kose S, 202166 | Turkey | Observational | <18 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: 11th March–11th June 2019, 11th March–11th June 2020) | 2019: 128 2020: 66 |

2019: 42 2020: 15 |

|

| Liu Y, 202183 | China | Cross-sectional | 9–18 | General population | Prevalence within the past 2 weeks (structured questionnaire administered in June 2020) | 5175 | 155 | |

| Llorca-Bofí V, 202267 | Spain | Observational | <18 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: January–March 2020, March–June 2020, October 2020–May 2021) | Jan–Mar 2020: 46 Mar–Jun 2020: 51 Oct 2020–May 2021: 245 |

Mar–Jun 2020: 11 Mar–Jun 2020: 15 Oct 2020–May 2021: 65 |

|

| McLoughlin A, 202268 | Ireland | Observational | <18 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: March–May) | 2019: 15 2020: 23 2021: 47 |

2019: 13 2020: 13 2021: 40 |

|

| Miles J, 202169 | USA | Observational | 2–18 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: January–December 2019, January–December 2020) | 2019: 1380 2020: 1380 |

2019: 655 2020: 277 |

|

| Millner AJ, 202270 | USA | Observational | 12–19 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence within the past month (time-period: March 2017–March 2020) | 2017–2020: 1096 2020–2021: 275 |

2017–2020: 827 2020–2021: 227 |

|

| Mohd Fadhli SA, 202271 | Malaysia | Cross-sectional | 13–17 | General population | Prevalence within the past 12 months (online survey, time-period: May–September 2021) | 1290 | 154 | |

| Murata S, 202172 | USA | Cross-sectional | 13–18 | General population | Prevalence (online survey, time-period: April–July 2020) | 583 | 156 | |

| Peng X, 202284 | China | Cross-sectional | 12–18 | General population | Prevalence within the past 2 weeks (April 2020) | 39,751 | 8069 | |

| Ridout KK, 202173 | USA | Cross-sectional | 5–17 | ED | Prevalence (time-period: 10th March–15th December 2019, 10th March–15th December 2020) | 2019: 104,293 2020: 48,207 |

2019: 2688 2020: 2481 |

|

| Sevecke K, 202275 | Germany | Observational | 6–18 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: January–December 2020, January–December 2021) | 2020: 383 2021: 538 |

2020: 187 2021: 264 |

|

| Shanmugavadivel D, 202185 | UK | Observational | 0–18 | ED | Prevalence (time-period: March–May) | 2019: 8813 2020: 4417 |

2019: 111 2020: 54 |

|

| She R, 202286 | China | Cross-sectional | 12–15 | General population | Prevalence within the past 2 weeks (time-period: September–November 2020) | 3080 | 918 | |

| Turner BJ, 202187 | Canada | Cross-sectional | 12–18 | General population | Prevalence within the past 4 months (structured questionnaire administered between June and July 2020) | 809 | 352 | |

| Zalsman G, 202188 | Israel | Observational | 10–17 | Psychiatric setting | Prevalence (time-period: January–June) | 2019: 1235 2020: 1598 |

2019: 246 2020: 250 |

|

| Zhang L, 202076 | China | Longitudinal cohort study | 9–16 | General population | Prevalence within the past 3 months (structured questionnaire administered in November 2019 and in May 2020) | 2019: 1271 2020: 1241 |

2019: 286 2020: 369 |

|

| Zhang Y, 202289 | China | Cross-sectional | 9–19 | General population | Prevalence within the past 2 weeks (online survey in February 2020) | 3471 | 115 | |

| Zhu S, 202190 | China | Longitudinal cohort study | 10–17 | General population | Prevalence within the past 2 weeks (structured questionnaire administered in September 2019 and in June 2020) | 2019: 1381 2020: 1381 |

2019: 336 2020: 291 |

|

| Zhu J, 202291 | China | Cross-sectional | 9–19 | General population | Prevalence during COVID-19 lockdown period (online survey in June 2020) | 5175 | 155 | |

Abbreviation: ED, emergency departments.

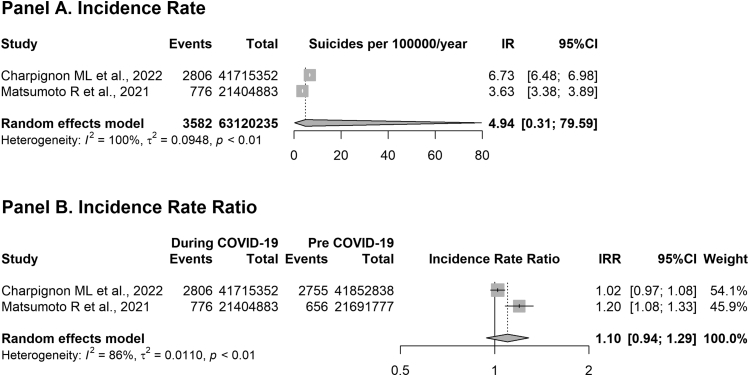

Six population-based studies reported suicide rates during COVID-19 pandemic, using data from the same official national sources in Japan32,46, 47, 48 and USA.49,50 However, only two of them, the most complete and comparable ones for each country, were included in the meta-analytic process.48,50 The results of the meta-analysis (Fig. 2) show a pooled annual IR of suicides of 4.9 cases/100,000 subjects under 20 years during 2020, accounting for a non-statistically significant increase of 10% compared to 2019 (IRR 1.10, 95% CI: 0.94–1.29).

Fig. 2.

Incidence rates of suicides for 100,000 young people during 2020 among general population (Panel A) and trend of suicides during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the pre-COVID-19 period (Panel B).

The other Japanese studies included in the narrative review observed that the suicide rate among young people was substantially steady during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.32,46,47 In particular, Tanaka and Okamoto reported a rate of about 3.2 suicides/million with an IRR of 0.98 (95% CI: 0.75–1.27) comparing the period between February and June 2020 with the years before (from November 2016 to January 2020).47 However, they also registered a rapid increase in the phenomenon during the second outbreak (from July to October 2020, 4.8 suicides/million), concurrently with school reopening (IRR: 1.49; 95% CI: 1.12–1.98). A similar increasing trend, even if non-statistically significant, was seen in 2020 in the USA by Ehlman et al. (IRR: 1.08; 95% CI: 0.96; 1.21).49 Moreover, Matsumoto et al. reported a statistically significant increase of suicides also in the first 6 months of 2021, compared to the pre-COVID-19 period (IRR: 1.18; 95% CI: 1.02–1.36).48

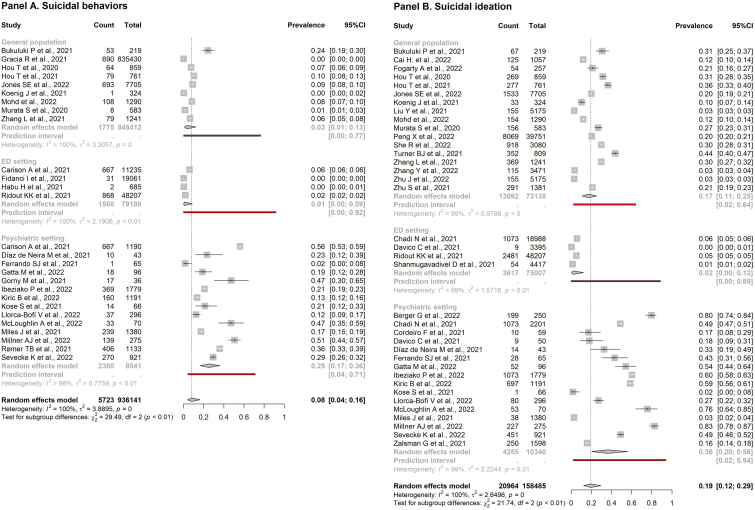

Fig. 3 reports the prevalence data of suicidal behaviors and suicidal ideation. The suicidal behaviors pooled prevalence (Panel A) during COVID-19 pandemic was 3% in the general population (95% CI: 1–13%), 1% in ED setting (95% CI: 0–9%) and 25% in psychiatric setting (95% CI: 17–36%). The pooled rate of suicidal ideation (Panel B) was 17% in general population (95% CI: 11–25%), 2% in ED setting (95% CI: 0–12%) and 36% in psychiatric setting (95% CI: 20–56%). Overall, the heterogeneity level is high for both outcomes and in all settings considered (99–100%).

Fig. 3.

Prevalence of suicidal behaviors (Panel A) and suicidal ideation (Panel B) among young people stratified by setting (general population, ED presentations for all causes and psychiatric setting). Abbreviation: ED, emergency department.

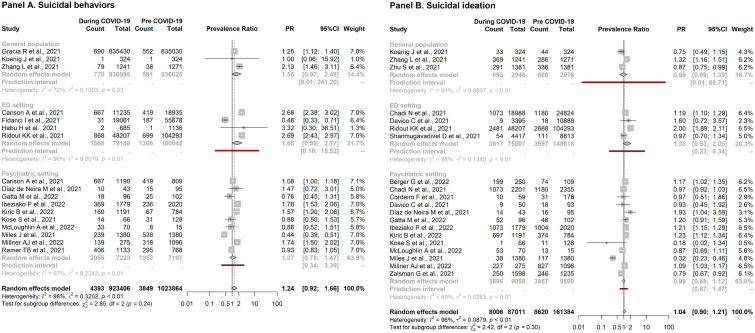

Among the 43 studies included in the meta-analysis, 16 out of 26 reported data about the comparison between before and during COVID-19 periods for suicidal behaviors52,53,55,56,58,59,62,64, 65, 66,68, 69, 70,73,74,76 and 18 out of 35 for suicidal ideation.53,56,62,64, 65, 66,68, 69, 70,73,76,77,79, 80, 81,85,88,90 Pooled prevalence in the two periods is similar for both suicidal measures and showed an overall stability over time in all the examined settings (Table 2, Fig. 4, Supplementary file 2, Figs. A2 and A3). A non-significant increasing trend could be observed in the PR of suicidal ideation and behaviors in all the settings considered (Table 2, Fig. 4). High heterogeneity levels could be observed (72–98%).

Table 2.

Meta-analytic results on studies reporting rates about pre- and during COVID-19 pandemic periods.

| No. of studies | Pre-COVID-19 (pooled prevalence, 95% CI) | During COVID-19 (pooled prevalence, 95% CI) | Estimated PR between pre- and during COVID-19 pandemic (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A. Suicidal behaviors | ||||

| General population | 3 | 0.00 (0.00–0.22) | 0.01 (0.00–0.44) | 1.55 (0.97–2.48) |

| ED setting | 4 | 0.01 (0.00–0.03) | 0.01 (0.00–0.09) | 1.65 (0.99–2.77) |

| Psychiatric setting (all periods) | 10 | 0.26 (0.17–0.39) | 0.29 (0.19–0.40) | 1.07 (0.78–1.47) |

| Only 2020 | 4 | 0.32 (0.14–0.57) | 0.28 (0.10–0.57) | 0.86 (0.46–1.60) |

| 2020–2021 | 6 | 0.23 (0.11–0.42) | 0.29 (0.16–0.46) | 1.26 (0.92–1.72) |

| Panel B. Suicidal ideation | ||||

| General population | 3 | 0.20 (0.11–0.34) | 0.19 (0.06–0.47) | 0·98 (0.69–1.39) |

| ED setting | 4 | 0.01 (0.00–0.09) | 0.02 (0.00–0.12) | 1.38 (0.93–2.05) |

| Psychiatric setting (all periods) | 13 | 0.36 (0.21–0.54) | 0.35 (0.16–0.60) | 0.99 (0.88–1.12) |

| Only 2020 | 7 | 0.18 (0.10–0.31) | 0.14 (0.04–0.35) | 0.79 (0.46–1.39) |

| 2020–2021 | 6 | 0.61 (0.45–0.75) | 0.69 (0.56–0.80) | 1.15 (1.04–1.27)a |

Abbreviations: PR, prevalence ratio; ED, emergency departments.

p < 0.05.

Fig. 4.

Trend of suicidal behaviors (Panel A) and suicidal ideation (Panel B) during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the pre-COVID-19 period. Analyses were performed according to setting (general population, ED presentations for all causes, psychiatric setting). Abbreviation: ED, emergency department.

The subgroup analysis according to the year of data collection could only be conducted in the psychiatric setting, due to the paucity of studies that allowed such grouping in the other two settings. In this framework (Supplementary file 1, Fig. A4), a higher prevalence estimate in the subgroup of studies collecting data during both 2020–2021 (62%; 95% CI: 46–76%) compared to that referred exclusively to 2020 (16%; 95% CI: 6–37%) could be observed for suicidal ideation. Moreover, the PR analysis (Table 2, Supplementary file 1, Fig. A5), showed a statistically significant increase of 15% (95% CI: 4–27%) in suicidal ideation among studies collecting data in a period including 2021. The same pattern could be observed also for suicidal behavior, without reaching the statistical significance.

The sensitivity analysis was performed to assess each study's effect on the pooled estimate. For the primary outcomes, results of both the find-outliers (Supplementary file 1, Fig. A6) and leave-one-out analyses (Supplementary file 1, Fig. A7) showed a slight overall difference in the estimate of both suicidal behaviors and suicidal ideation, confirming the robustness of our analysis. For secondary outcomes, the find-outliers and the leave-one-out analyses showed a shift toward the statistical significance of the PR estimates for suicidal behaviors in both the general population (2.10; 95% CI: 1.44–3.06 without Gracia et al.; 1.25; 95% CI: 1.12–1.40, without Zhang et al.) and the ED setting (2.69; 95% CI: 2.49–2.90, removing Fidanci et al.), with the disappearance of heterogeneity (Supplementary file 1, Figs. A8 and A9). Results of the random-effects meta-regressions (assessing the potential effect of the country and the recall period in questionnaires) and of the sensitivity analysis based on studies' quality are reported in the Supplementary file 1 (Tables A5 and A6 and Figs. A10 and A11).

Discussion

The present systematic review and meta-analysis focuses on the phenomenon of suicidality in under 19 years old during COVID-19 pandemic. Suicide, suicidal behaviors, and suicidal ideation rates were reported for general population, youths presenting to ED and psychiatric services. In agreement with Van Heeringen's pyramid of suicide,7 an overall increasing prevalence has been detected from suicide to suicidal ideation.

The suicide outcome showed an overall homogeneous pattern during the explored period, with an upward trend in 2020 compared to the previous year. Both suicidal behaviors and suicidal ideation showed a higher prevalence in the psychiatric setting than in the ED setting or in the general population. Furthermore, comparing pre-pandemic and during-COVID-19 periods, a non-statistically significant increase has been observed for both suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior prevalences within the three settings explored. A statistically significant escalating trend was seen for suicidal ideation in the psychiatric setting pooling studies referred to the most recent data (until 2021).

Since the aforementioned Van Heeringen's conceptualization describes the suicidality phenomenon as a symptomatologic continuum, the three outcomes should be discussed together to better understand this complex public health issue.6,7 However, at the same time, the settings (general population, ED, and psychiatric setting) taken into account are very heterogeneous, therefore the discussion of the phenomenon as a whole will be contextualised on the basis of the settings explored.

Studies reporting suicide deaths included in the meta-analysis have been conducted only in the general population setting, showing a pooled incidence rate of 4.94/100,000 under 19 years in 2020. Overall, an increasing trend was observed in the suicides IRs in 2020 compared to 2019. In particular, Anzai,46 Isumi32 and Tanaka47 reported an overall stability in suicides during the first phases of the COVID-19 pandemic until August 2020 among young people. Later, from August, suicide cases started to increase compared to the same period in 2019, presumably until at least June 2021, as reported by Matsumoto et al.48 A similar trend was previously observed during the past epidemics (e.g. Spanish flu epidemic, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) and in concomitance with natural disasters (e.g. tsunamis, earthquakes, hurricanes).92, 93, 94, 95

From the results of the present study, it appears that about 1 out of 33 adolescents (3%; 95% CI: 1–13%) in different population-based settings (schools, online surveys, non-governmental organizations) attempted suicide or manifested suicidal behaviors, while 1 out of 6 (17%; 95% CI: 11–25%) presented at least suicidal ideation during COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, according to our estimates, suicidal symptomatology seems to have been relevant also in the pre-COVID-19 period, in agreement with other studies.96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101 In fact, the pooled prevalences obtained from the two periods were similar.

These findings pointed out the relevance of such outcomes during youth, considering adolescence at higher risk of developing suicidal thoughts. Several authors suggested that it could be a period of imbalance between a heightened sensitivity to motivational clues and an immature cognitive control, which could hamper the impulse inhibition to self-harm.2, 3, 4,102 However, in agreement with the pyramid of suicide, suicidal thoughts and behaviors still represent just weak predictors of future suicide.7, 8, 9

The comparison between the pre- and during pandemic periods suggested a more complex picture: among the general population under 19 years old, suicidal ideation resulted steady over time, while suicidal behaviors increased by 55%, even if the result is not statistically significant (PR: 1.55; 95% CI: 0.97–2.48). It is important to note that only two of the studies included in the meta-analysis have a longitudinal design (the most appropriate design to explore such outcomes), exploring the suicidal symptomatology in different population-based cohorts of Chinese students before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.76,90 However, they reported contrasting results on suicidal ideation trend: if Zhu et al. found a statistically significant slight decrease (PR: 0.87; 95% CI: 0.75–0.99),90 Zhang et al. observed a statistically significant increase (PR: 1.32; 95% CI: 1.16–1.51).76 In this framework, the suicidal behaviors could be more susceptible to the COVID-19 exposure than suicidal ideation, enforcing the hypothesis that the first phases of pandemic could have led to a fast worsening of previous mental conditions rather than to the onset of suicidal symptoms among healthy young people.103

The overall initial stability observed in these analyses could be interpreted as a preamble of an increasing trend, not only for suicide rates (i.e. in USA, Malawi, Japan),46,47,104,105 but also for suicidal behaviors, as already evidenced in Spain, USA and China,58,76,106 and suicidal ideation, as observed in UK, USA and China.76,106,107 Among possible explanations for this non-homogeneous trend over time, not analytically explored here for lack of available data, some authors suggested the initial positive compensatory role of school closures on the adolescents' mental health,20,21,32,47 also called “honeymoon effect”, already observed in concomitance with other natural disasters.14,20,21,92,93 Later, school re-openings in the Autumn 2020 could have represented a further stressful element that could have contributed to an increase in suicidality.32,47 From this point of view, while the first pandemic wave could have worsened mental health in terms of levels of social isolation, depression, and anxiety, the second wave could have furtherly increased suicidal symptomatology.22,25,31,108,109 In support of this hypothesis, “too much worries” and suicidal thoughts were increasingly correlated in a subsequent period compared to the outbreak stage, according to a network analysis of symptoms of anxiety and depression in young Chinese people.110

In contrast with the general population, exploring suicidality in a clinical setting (ED and psychiatric settings) allows focusing the attention on subjects with a greater fragility which are more predisposed to the phenomenon. This meta-analysis found a pooled prevalence of 1% of suicidal behaviors and 2% of suicidal ideation among pediatric EDs visits. These estimates are significantly lower than for the general population, confirming that the overall arrivals to health services due to problems related to suicidality probably are just the tip of the iceberg: the greatest part of the phenomenon lies below the waterline, rooted in the community and often underdiagnosed or hidden.4,10,12 Furthermore, the suicidal phenomenon (i.e. all outcomes explored in this meta-analysis), especially during the young age, is still steeped in social stigma, and academic research, prevention policies, and early identification of subjects at risk are often hampered.4,10

Compared to the pre-COVID-19 period, a 65% increasing prevalence of suicidal behaviors was observed in the ED setting, even if the estimate was not statistically significant (crude PR: 1.65; 95% CI: 0.99–2.77). This result could reflect an increase in suicidal symptomatology but also a reduction in arrivals for several other acute medical conditions, mainly communicable infections and gastrointestinal disorders,111,112 due to both the lower incidence associated with the containment measures during lockdown and the fear of contagion.113,114 According to a report by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), this increasing trend in suicidal behaviors might have started in the USA during Summer 2020 and it might have been stable until at least mid-May 2021, corresponding to the end of the study period.115 Similar temporal trends have been already seen in Australia, UK and Germany.116, 117, 118, 119

In the psychiatric setting, pooled estimates reported about 1 out of 4 subjects (25%; 95% CI: 17–36%) showing suicidal behaviors and about 1 out of 3 (36%; 95% CI: 20–56%) presenting suicidal ideation, confirming this one as a very specific context, with a particularly high prevalence of the phenomenon.7,11,12 It is known that suicidal symptomatology is very common in psychiatric setting and it is strongly associated with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), dysthymia, and panic disorder diagnoses,31 all conditions whose prevalence seemed to be significantly increased after the COVID-19 outbreak.30,120 Compared to the pre-COVID-19 period, no statistically significant changes were observed for the suicidal outcomes in this specific setting, however an increase of 15% in suicidal ideation was reported by studies collecting 2020–2021 data (PR 1.15; 95% CI: 1.04–1.27). The same pattern could be observed also for suicidal behavior, without reaching the statistical significance. These results agreed with what has been reported by other authors: in both clinical settings (ED and psychiatric one), after a slight decline in psychiatric visit rates, a subsequent growth of all-mental-causes and suicidal presentations have been registered from Summer 2020 until the end of the Winter 2021.115,121 Such a pattern seems to suggest a time-dependent characteristic of the phenomenon.56,64,122 A possible explanation for what has just been reported is that the fear of contagion, especially in the first months of the pandemic, might have deterred adolescents from asking for psychiatric care, so that most cases were probably left behind in the community, underdiagnosed and undertreated.4,53,121 Moreover, the strict pandemic containment policies may have helped to restrain the phenomenon by increasing the time spent in the household by children and adolescents.20 Later, as the pandemic progressed, the suicidality (both suicidal ideation and behaviors) might have become an emerging comorbid symptomatology, more commonly observed even among young people suffering primarily from other psychiatric conditions.123

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first quantitative synthesis of different suicidal outcomes in the under 19-year-old population during the COVID-19 pandemic. There are three main strengths of this study. First, the overall sample size of more than 65 million subjects could be optimal for quantifying the rates of suicidal phenomena among young people. Second, the use of strict inclusion criteria during the screening of the studies allowed a rigorous focus on the outcomes of interest. Third, the analysis according to different settings helps to better describe these phenomena and contribute to driving public health policy-making decisions.

This study also has several limitations. The included studies are heterogeneous in terms of study design: most of them are cross-sectional, while only two provide a longitudinal design, the most appropriate strategy to investigate the explored outcomes. Globally, all the studies were observational, being potentially subject to different kinds of bias. Some of the studies recruited convenience samples of volunteers through online surveys, which implies that the volunteers have access to the internet, thus not necessarily reflecting the entire population (e.g. the youngest could be less represented). Moreover, it seems that people in distress or with co-existing mental illness are less inclined to participate in this type of survey, undermining the sample's representativeness.124 We are also aware that only few studies from low-income countries have been found and included in this meta-analysis, confirming that suicidality is still largely poorly monitored in several countries, especially in the global South. Another limitation is represented by the heterogeneous timing of data collection within the studies, which did not allow us to stratify the analyses according to the adoption of different and changing grading of containment measures. The diagnostic tools used for outcomes assessment were also not homogeneous, ranging from validated questionnaires to specific questions in online surveys, to ICD-10 suicidality codes, potentially contributing to the heterogeneity across studies. In particular, for the questionnaires, different possible recall periods were identified in the studies (from 2 weeks to 1 year). Although the sensitivity analysis didn't confirm this potential source of bias, this issue cannot be further addressed at this stage and will require future investigations. A further limitation is that the time from the beginning of the exposure to the COVID-19 pandemic and the detection of the outcomes could not be sufficient to observe the true impact of the pandemic on the suicidal outcomes. To differentiate the specific effects of pandemic from potential trends already in progress before the COVID-19 outbreak, both longitudinal and time-series studies are desirable to better interpret the global trend of suicidality in the pandemic years.

In conclusion, this systematic review and meta-analysis provides a first synthesis of the most up-to-date evidence on suicidality among young people under the age of 19 after the COVID-19 outbreak. During the pandemic, suicides, suicidal behaviors, and suicidal ideation seemed to follow the known pattern described in the Van Heeringen's pyramid of suicide. Overall, the prevalence of suicidal ideation was higher than that of suicidal behaviors, even if it greatly varied among clinical settings, with higher levels in psychiatric setting than in EDs. Compared to the pre COVID-19 prevalence, an overall increase in suicidal behaviors could be observed among ED's presentations and in general population setting, while suicidal ideation rates remained steady in all the settings considered, except for an escalating trend reported in the psychiatric setting by studies collecting the most recent data (2020–2021). Qualitative/quantitative data on suicide rates described an overall annual increasing trend in 2020 compared to 2019, especially since Summer 2020, after an initial stability of the phenomenon. This pattern has been reported also for suicidal behaviors and suicidal ideation, suggesting a potential involvement of school closures and strict lockdown policies during the first phases of the pandemic as an initial protective factor for suicidality. After the reopenings, we could have assisted to a sort of rebound, in which long-lasting COVID-19 related worries and a potentially hard adaptation to frequent social interactions after months of limitations could have strongly affected the most vulnerable youth's mental health.

These findings have great relevance from both a clinical and a public health point of view. Understanding whether and how adolescents' mental health has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic can allow the implementation of tailored policies to prevent and control suicidal phenomena, and to improve the quality of life of this particularly susceptible population. In this framework, we would address three main tailored policy strategies. First, prompt action should be focused on preventing the escalation from suicidal ideation to suicidal behaviors that our findings seem to suggest. Secondly, social rehabilitation policies are desirable to improve the recovery of young people who have already experienced suicidal behaviors since the early months of the pandemic. Third, from a wider perspective, the present work calls for urgent investments in the mental health area aimed at offering the young people easy and free access to the services, both in schools and in other public institutions, to enable the early detection of mental disorders and the prevention of the escalation into suicidality. However, literature about youth suicidality during COVID-19 is still expanding and further research is needed to clarify this complex clinical and public health issue.

Contributors

RIC and MB designed the study and drafted the manuscript. RIC, MB and EK contributed to the search strategy, screening of articles, and data collection. RIC, MB and EK contributed to the risk of bias assessment and made the tables and figures. RIC, MB and EK contributed to data analysis and interpretation. MB, EK, PB, LC, AR, PG, PD and RIC contributed to critical revision of manuscript for intellectually important content. All authors provided critical conceptual input, interpreted the data analysis, and read and approved the final draft of the manuscript. MB, EK and RIC accessed and verified the data. MB and RIC were responsible for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Data sharing statement

This manuscript makes use of publicly available data from the included studies and their supplementary information files; therefore, no original data are available for sharing.

Declaration of interests

All authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101705.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.WHO . World Health Organization; 2021. Suicide worldwide in 2019: Global Health Estimates. Geneva. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casey B., Jones R.M., Somerville L.H. Braking and accelerating of the adolescent brain. J Res Adolesc. 2011;21(1):21–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00712.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brezo J., Paris J., Barker E.D., et al. Natural history of suicidal behaviors in a population-based sample of young adults. Psychol Med. 2007;37(11):1563–1574. doi: 10.1017/S003329170700058X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawton K., Saunders K.E.A., O'Connor R.C. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet. 2012;379(9834):2373–2382. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sebastian C., Viding E., Williams K.D., Blakemore S.J. Social brain development and the affective consequences of ostracism in adolescence. Brain Cognit. 2010;72(1):134–145. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paykel E.S., Myers J.K., Lindenthal J.J., Tanner J. Suicidal feelings in the general population: a prevalence study. Br J Psychiatry. 1974;124(0):460–469. doi: 10.1192/bjp.124.5.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Heeringen K. Wiley; 2002. Understanding Suicidal Behaviour: The Suicidal Process Approach to Research, Treatment and Prevention.https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Understanding+Suicidal+Behaviour%3A+The+Suicidal+Process+Approach+to+Research%2C+Treatment+and+Prevention-p-9780471491668 [Internet] [cited 2022 Apr 11]. 340 p. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ribeiro J.D., Franklin J.C., Fox K.R., et al. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors as risk factors for future suicide ideation, attempts, and death: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Med. 2016 Jan;46(2):225–236. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715001804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO . World Health Organization; 2014. Preventing suicide: a global imperative.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/131056 [cited 2022 Mar 20]. 89 p. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nathan N.A., Nathan K.I. Suicide, stigma, and utilizing social media platforms to gauge public perceptions. Front Psychiatr. 2020 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00947. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00947 [cited 2022 Apr 11]; 10. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawton K., Cole D., O'Grady J., Osborn M. Motivational aspects of deliberate self-poisoning in adolescents. Br J Psychiatr. 1982;141:286–291. doi: 10.1192/bjp.141.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kemball R.S., Gasgarth R., Johnson B., Patil M., Houry D. Unrecognized suicidal ideation in ED patients: are we missing an opportunity? Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26(6):701–705. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burstein B., Agostino H., Greenfield B. Suicidal attempts and ideation among children and adolescents in US emergency departments, 2007-2015. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(6):598–600. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bersia M., Berchialla P., Charrier L., et al. Mental well-being: 2010-2018 trends among Italian adolescents. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2022;19(2):863. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19020863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krokstad S., Weiss D.A., Krokstad M.A., et al. Divergent decennial trends in mental health according to age reveal poorer mental health for young people: repeated cross-sectional population-based surveys from the HUNT Study, Norway. BMJ Open. 2022;12(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerstner R.M., Lara Lara F. [Trend analysis of suicide among children, adolescent and young adults in Ecuador between 1990 and 2017] An Sist Sanit Navar. 2019;42(1):9–18. doi: 10.23938/ASSN.0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cosma A., Stevens G., Martin G., et al. Cross-national time trends in adolescent mental well-being from 2002 to 2018 and the explanatory role of schoolwork pressure. J Adolesc Health. 2020;66(6S):S50–S58. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan C., Webb R.T., Carr M.J., et al. Incidence, clinical management, and mortality risk following self harm among children and adolescents: cohort study in primary care. BMJ. 2017;359:j4351. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ivey-Stephenson A.Z., Demissie Z., Crosby A.E., et al. Suicidal ideation and behaviors among high school students - youth risk behavior survey, United States, 2019. MMWR. 2020;69(1):47–55. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su6901a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fegert J.M., Vitiello B., Plener P.L., Clemens V. Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: a narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Ment Health. 2020;14:20. doi: 10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoekstra P.J. Suicidality in children and adolescents: lessons to be learned from the COVID-19 crisis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 2020;29(6):737–738. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01570-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Araújo L.A., Veloso C.F., de Souza M.C., de Azevedo J.M.C., Tarro G. The potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on child growth and development: a systematic review. J Pediatr. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2020.08.008. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7510529/ [cited 2021 Nov 11]; Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.John A., Eyles E., Webb R.T., et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on self-harm and suicidal behaviour: update of living systematic review. F1000Res. 2020;9:1097. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.25522.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jolly T.S., Batchelder E., Baweja R. Mental health crisis secondary to COVID-19-related stress: a case series from a child and adolescent inpatient unit. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2020;22(5):20l02763. doi: 10.4088/PCC.20l02763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magson N.R., Freeman J.Y.A., Rapee R.M., Richardson C.E., Oar E.L., Fardouly J. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Youth Adolesc. 2020:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orben A., Tomova L., Blakemore S.J. The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(8):634–640. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30186-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown S.M., Doom J.R., Lechuga-Peña S., Watamura S.E., Koppels T. Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;110(Pt 2) doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klasen F., Otto C., Kriston L., et al. Risk and protective factors for the development of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: results of the longitudinal BELLA study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 2015;24(6):695–703. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0637-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruiz-Robledillo N., Ferrer-Cascales R., Albaladejo-Blázquez N., Sánchez-SanSegundo M. Family and school contexts as predictors of suicidal behavior among adolescents: the role of depression and anxiety. J Clin Med. 2019;8(12):E2066. doi: 10.3390/jcm8122066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chadi N., Ryan N.C., Geoffroy M.C. COVID-19 and the impacts on youth mental health: emerging evidence from longitudinal studies. Can J Public Health. 2022;113(1):44–52. doi: 10.17269/s41997-021-00567-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miché M., Hofer P.D., Voss C., et al. Mental disorders and the risk for the subsequent first suicide attempt: results of a community study on adolescents and young adults. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 2018;27(7):839–848. doi: 10.1007/s00787-017-1060-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Isumi A., Doi S., Yamaoka Y., Takahashi K., Fujiwara T. Do suicide rates in children and adolescents change during school closure in Japan? The acute effect of the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic on child and adolescent mental health. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;110(Pt 2) doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.AACAP A. American Academy of Pediatrics, and Children’s Hospital Association; 2021. Declaration from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/Docs/press/Declaration_National_Crisis_Oct-2021.pdf American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gruber J., Prinstein M.J., Clark L.A., et al. Mental health and clinical psychological science in the time of COVID-19: challenges, opportunities, and a call to action. Am Psychol. 2021;76(3):409–426. doi: 10.1037/amp0000707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holmes E.A., O'Connor R.C., Perry V.H., et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020;7(6):547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iskander J.K., Crosby A.E. Implementing the national suicide prevention strategy: time for action to flatten the curve. Prev Med. 2021;152(Pt 1) doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., Group T.P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwarzer G., Chemaitelly H., Abu-Raddad L.J., Rücker G. Seriously misleading results using inverse of Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation in meta-analysis of single proportions. Res Synth Methods. 2019;10(3):476–483. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clopper C.J., Pearson E.S. The use of confidence or fiducial limits illustrated in the case of the binomial. Biometrika. 1934;26(4):404–413. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Higgins J.P.T., Thompson S.G., Deeks J.J., Altman D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Viechtbauer W., Cheung M.W.L. Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1(2):112–125. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.R Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2021. R: A language and environment for statistical computing.https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 43.Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Software. 2010;36:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hunter J.P., Saratzis A., Sutton A.J., Boucher R.H., Sayers R.D., Bown M.J. In meta-analyses of proportion studies, funnel plots were found to be an inaccurate method of assessing publication bias. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(8):897–903. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Munn Z., Moola S., Riitano D., Lisy K. The development of a critical appraisal tool for use in systematic reviews addressing questions of prevalence. Int J Health Pol Manag. 2014;3(3):123–128. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anzai T., Fukui K., Ito T., Ito Y., Takahashi K. Excess mortality from suicide during the early COVID-19 pandemic period in Japan: a time-series modeling before the pandemic. J Epidemiol. 2021;31(2):152–156. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20200443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tanaka T., Okamoto S. Increase in suicide following an initial decline during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. Nat Human Behav. 2021;5(2):229–238. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-01042-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsumoto R., Motomura E., Fukuyama K., Shiroyama T., Okada M. Determining what changed Japanese suicide mortality in 2020 using governmental database. J Clin Med. 2021;10(21):5199. doi: 10.3390/jcm10215199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ehlman D.C., Yard E., Stone D.M., Jones C.M., Mack K.A. Changes in suicide rates - United States, 2019 and 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(8):306–312. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7108a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Charpignon M.L., Ontiveros J., Sundaresan S., et al. Evaluation of suicides among us adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(7):724–726. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.0515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bukuluki P., Wandiembe S., Kisaakye P., Besigwa S., Kasirye R. Suicidal ideations and attempts among adolescents in kampala urban settlements in Uganda: a case study of adolescents receiving care from the Uganda youth development link. Front Sociol. 2021;6 doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2021.646854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carison A., Babl F.E., O'Donnell S.M. Increased paediatric emergency mental health and suicidality presentations during COVID-19 stay at home restrictions. Emerg Med Australasia (EMA) 2022;34(1):85–91. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.13901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Díaz de Neira M., Blasco-Fontecilla H., García Murillo L., et al. Demand analysis of a psychiatric emergency room and an adolescent acute inpatient unit in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic in madrid, Spain. Front Psychiatr. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.557508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ferrando S.J., Klepacz L., Lynch S., et al. Psychiatric emergencies during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in the suburban New York City area. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;136:552–559. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fidancı İ., Taşar M.A., Akıntuğ B., Fidancı İ., Bulut İ. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on paediatric emergency service. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(9) doi: 10.1111/ijcp.14398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gatta M., Raffagnato A., Mason F., et al. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of paediatric patients admitted to a neuropsychiatric care hospital in the COVID-19 era. Ital J Pediatr. 2022;48(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s13052-022-01213-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gorny M., Blackstock S., Bhaskaran A., et al. Working together better for mental health in children and young people during a pandemic: experiences from North Central London during the first wave of COVID-19. BMJ Paediatrics Open. 2021;5(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2021-001116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gracia R., Pamias M., Mortier P., Alonso J., Pérez V., Palao D. Is the COVID-19 pandemic a risk factor for suicide attempts in adolescent girls? J Affect Disord. 2021;292:139–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Habu H., Takao S., Fujimoto R., Naito H., Nakao A., Yorifuji T. Emergency dispatches for suicide attempts during the COVID-19 outbreak in Okayama, Japan: a descriptive epidemiological study. J Epidemiol. 2021;31(9):511–517. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20210066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hou T.Y., Mao X.F., Dong W., Cai W.P., Deng G.H. Prevalence of and factors associated with mental health problems and suicidality among senior high school students in rural China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;54 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hou T., Mao X., Shao X., Liu F., Dong W., Cai W. Suicidality and its associated factors among students in rural China during COVID-19 pandemic: a comparative study of left-behind and non-left-behind children. Front Psychiatr. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.708305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ibeziako P., Kaufman K., Scheer K.N., Sideridis G. Pediatric mental health presentations and boarding: first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Hosp Pediatr. 2022;12(9):751–760. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2022-006555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jones S.E. Mental health, suicidality, and connectedness among high school students during the COVID-19 pandemic — adolescent behaviors and experiences survey, United States, January–June 2021. MMWR (Morb Mortal Wkly Rep) 2022 doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su7103a3. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/su/su7103a3.htm Suppl [Internet] [cited 2022 Sep 13];71. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kirič B., Leben Novak L., Lušicky P., Drobnič Radobuljac M. Suicidal behavior in emergency child and adolescent psychiatric service users before and during the 16 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatr. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.893040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Koenig J., Kohls E., Moessner M., et al. The impact of COVID-19 related lockdown measures on self-reported psychopathology and health-related quality of life in German adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 2021:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01843-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kose S., Inal-Kaleli I., Senturk-Pilan B., et al. Effects of a pandemic on child and adolescent psychiatry emergency admissions: early experiences during the COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J Psychiatr. 2021;61 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Llorca-Bofí V., Irigoyen-Otiñano M., Sánchez-Cazalilla M., et al. Urgent care and suicidal behavior in the child and adolescent population in a psychiatric emergency department in a Spanish province during the two COVID-19 states of alarm. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.rpsm.2022.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McLoughlin A., Abdalla A., Gonzalez J., Freyne A., Asghar M., Ferguson Y. Locked in and locked out: sequelae of a pandemic for distressed and vulnerable teenagers in Ireland: post-COVID rise in psychiatry assessments of teenagers presenting to the emergency department out-of-hours at an adult Irish tertiary hospital. Ir J Med Sci. 2022;23:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11845-022-03080-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miles J., Zettl R. 44.9 impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide attempts and suicidal ideations in youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatr. 2021;60(10):S240. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Millner A.J., Zuromski K.L., Joyce V.W., et al. Increased severity of mental health symptoms among adolescent inpatients during COVID-19. Gen Hosp Psychiatr. 2022;77:77–79. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2022.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mohd Fadhli S.A., Liew Suet Yan J., Ab Halim A.S., Ab Razak A., Ab Rahman A. Finding the link between cyberbullying and suicidal behaviour among adolescents in peninsular Malaysia. Healthcare. 2022;10(5):856. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10050856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Murata S., Rezeppa T., Thoma B., et al. The psychiatric sequelae of the COVID-19 pandemic in adolescents, adults, and health care workers. Depress Anxiety. 2021;38(2):233–246. doi: 10.1002/da.23120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ridout K.K., Alavi M., Ridout S.J., et al. Emergency department encounters among youth with suicidal thoughts or behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatr. 2021;78(12):1319–1328. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rømer T.B., Christensen R.H.B., Blomberg S.N., Folke F., Christensen H.C., Benros M.E. Psychiatric admissions, referrals, and suicidal behavior before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Denmark: a time-trend study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2021;144(6):553–562. doi: 10.1111/acps.13369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sevecke K., Wenter A., Schickl M., Kranz M., Krstic N., Fuchs M. Stationäre Versorgungskapazitäten in der Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie – Zunahme der Akutaufnahmen während der COVID-19 Pandemie? Neuropsychiatry. 2022:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s40211-022-00423-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang L., Zhang D., Fang J., Wan Y., Tao F., Sun Y. Assessment of mental health of Chinese primary school students before and after school closing and opening during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Berger G., Häberling I., Lustenberger A., et al. The mental distress of our youth in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Swiss Med Wkly. 2022;152 doi: 10.4414/smw.2022.w30142. w30142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cai H., Bai W., Liu H., et al. Network analysis of depressive and anxiety symptoms in adolescents during the later stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41398-022-01838-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chadi N., Spinoso-Di Piano C., Osmanlliu E., Gravel J., Drouin O. Mental health-related emergency department visits in adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multicentric retrospective study. J Adolesc Health. 2021;69(5):847–850. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cordeiro F., Santos V., Cartaxo T. Suicidal ideation during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic in a child and adolescent psychiatry emergency care sample. Eur Psychiatr. 2021 Apr;64(S1):S639. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Davico C., Marcotulli D., Lux C., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on child and adolescent psychiatric emergencies. J Clin Psychiatr. 2021;82(3):20m13467. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20m13467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fogarty A., Brown S., Gartland D., et al. Psychosocial factors associated with adolescent depressive and anxiety symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. IJBD (Int J Behav Dev) 2022;46(4):308–319. [Google Scholar]