Abstract

Chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients is almost impossible to eradicate with antibiotic treatment. In the present study, the effects of treatment with the Chinese herbal medicine ginseng on blood polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) chemiluminescence and serum specific antibody responses were studied in a rat model of chronic P. aeruginosa pneumonia mimicking CF. An aqueous extract of ginseng was administered by subcutaneous injection at a dosage of 25 mg/kg of body weight/day for 2 weeks. Saline was used as a control. Two weeks after the start of ginseng treatment, significantly increased PMN chemiluminescence (P ≤ 0.001) and a decreased level in serum of immunoglobulin G (IgG) against P. aeruginosa (P < 0.05) were found. Furthermore, a higher IgG2a level (P < 0.04) but lower IgG1 level (P < 0.04) were found in the ginseng-treated infected group than in the control group. In the ginseng-treated group the macroscopic lung pathology was milder (P = 0.0003) and the percent PMNs in the cells collected by bronchoalveolar lavage was lower (P = 0.0006) than in the control group. However, the alveolar macrophage (AM) chemiluminescence values were not significantly different in the two groups infected with P. aeruginosa. The differences between the ginseng-treated noninfected rats and the control group (without P. aeruginosa lung infection) for the PMN chemiluminescence and AM chemiluminescence were not significant. These results suggest that ginseng treatment leads to an activation of PMNs and modulation of the IgG response to P. aeruginosa, enhancing the bacterial clearance and thereby reducing the formation of immune complexes, resulting in a milder lung pathology. The changes in IgG1 and IgG2a subclasses indicate a possible shift from a Th-2-like to a Th-1-like response. These findings indicate that the therapeutic effects of ginseng may be related to activation of a Th-1 type of cellular immunity and down-regulation of humoral immunity.

Chronic and recurrent Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection is the major cause of morbidity and mortality in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients. The prevalence of chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection in CF patients is about 60% (1), and most of these patients are infected by alginate-producing strains (15) associated with poor prognosis. The pathogenesis of the infection is dominated by a pronounced immune complex-mediated inflammation where proteases from polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) destroy the lung tissues. The infection is almost impossible to eradicate with antibiotic treatment because of the biofilm mode of growth and the development of antibiotic resistance by the bacteria (1, 3). It is therefore important to search for alternative infection control measures.

Previously we have shown that ginseng treatment reduces bacterial load and lung pathology in both normal and athymic rats chronically infected with mucoid P. aeruginosa (18, 19). However, the mechanism by which it exerts this effect is not clear. In the present study, we have evaluated the effect of ginseng treatment on the oxidative burst response of peripheral blood neutrophils and alveolar macrophages (AM) in a rat model of chronic mucoid P. aeruginosa lung infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

One hundred four female Lewis rats (Charles River, Würzburg, Germany) 7 weeks old with body weights of approximately 150 g were used.

Challenge strain of P. aeruginosa.

P. aeruginosa PAO 579 (kindly provided by J. R. W. Govan, Department of Bacteriology, Medical School, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom), which stably maintains a mucoid phenotype and which is type O:2/5 according to the international antigenic typing system, was used in our study (7).

Immobilization of P. aeruginosa in seaweed alginate beads.

Immobilization of P. aeruginosa in seaweed alginate beads was done as described previously (8, 16). In brief, 1 ml of the P. aeruginosa bacterial culture was mixed with 9 ml of seaweed alginate (60% guluronic acid content), and the mixture was forced once with air through a cannula into a solution of 0.1 M CaCl2 in 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.0). The suspension was adjusted to yield 109 CFU/ml, and the yield was confirmed by colony counts.

Treatment protocol.

Rats were divided into four groups.

(i) Ginseng group 1.

Panax ginseng (C. A. Meyer) (ginseng) (6) powder was provided by Millingwang Limited, Jilin, People’s Republic of China. An aqueous extract of ginseng was prepared as described previously (18, 19). In brief, after 2.5 g of ginseng powder was mixed with 100 ml of distilled water at room temperature for 20 min, the mixture was heated at 90°C for 30 min and filtered through sterile filter paper twice before use (final concentration, 25 mg of dry-powder equivalent per ml). The concentration of protein in the ginseng extract was 3.5 mg/ml (18), and that of the endotoxin-like material was 60 ng/ml (18), which is 1,660 times lower than the dose of lipopolysaccharide members of our group used in another study (12). The ginseng solution was injected subcutaneously into 40 rats with P. aeruginosa lung infection at 25 mg/kg of body weight once a day for 14 days.

(ii) Control group 1.

In 40 rats with P. aeruginosa lung infection, sterile saline (0.9%) was injected subcutaneously at 1 ml/kg of body weight once a day for 14 days.

(iii) Ginseng group 2.

In 12 noninfected rats, the ginseng extract was administered subcutaneously at a dose of 25 mg/kg of body weight once a day for 14 days.

(iv) Control group 2.

In 12 noninfected rats, sterile saline was injected subcutaneously at 1 ml/kg of body weight once a day for 14 days.

Challenge procedures and blood sample collection.

At the time of challenge, all rats were anesthetized by subcutaneous injection of a 1:1 mixture of etomidate (Janssen, Birkerød, Denmark) and midazolam (Roche, Hvidovre, Denmark) at a dose of 1.5 ml/kg of body weight and tracheotomized (7). Intratracheal challenge with 0.1 ml of the mixture of P. aeruginosa (109 CFU/ml) and alginate beads was performed as described previously (7). The incision was sutured with silk thread and healed without any complications. Fourteen days after challenge, all rats were sacrificed by injection of 20% pentobarbital (DAK, Copenhagen, Denmark) at 3 ml/kg of body weight, and blood samples were obtained by cardiac puncture.

The challenge and the start of administration of ginseng or saline were on the same day.

Macroscopic pathology of the lungs.

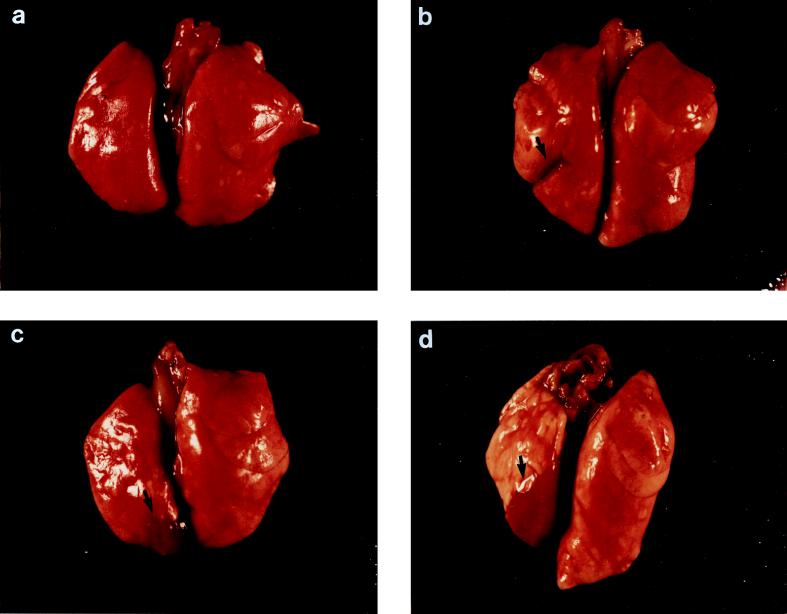

The macroscopic lung pathology was expressed as the lung index of macroscopic pathology (LIMP), which was calculated by dividing the area of the left lung showing pathologic changes by the total area of the same lung (2). In addition, the gross pathological changes in the lungs were also assigned four different scores according to the severity of the inflammation (Fig. 1a to d) as previously described (7, 8, 18): I, normal lungs; II, swollen lungs, hyperemia, and small atelectasis (<10 mm2); III, pleural adhesions and atelectasis (<40 mm2); and IV, abscesses, large atelectasis, and hemorrhages.

FIG. 1.

Illustrations of gross lung pathology in rats. (a) Normal lung; (b) small lung atelectasis (<10 mm2); (c) moderate atelectasis (>10 mm2 but <40 mm2); (d) larger atelectasis or lung with abscess.

Histopathologic scoring.

For 10 of the animals in each group lung histological examination was performed as described previously (7). The lung pathology was assigned microscopically one of four scores according to the severity of the inflammation, as follows: 1, normal histology; 2, mild focal inflammation; 3, moderate to severe focal inflammation with areas of normal lung tissue; and 4, severe inflammation to necrosis or severe inflammation throughout the lung. The cellular alterations were classified as acute or chronic inflammation by a scoring system based on the proportions of neutrophils (PMNs) and mononuclear leukocytes (MNs) in the inflammatory foci. Acute inflammation was defined as an inflammatory infiltration in which PMNs were predominant (≥90% PMNs with ≤10% MNs), whereas chronic inflammation was defined as a preponderance of MNs (≥90% with ≤10% PMNs), which included lymphocytes and plasma cells, and the presence of granulomas (3, 7).

Differential count of cells obtained by BAL.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed with cold saline (4°C) in half of the sacrificed rats. The cells were then collected from the BAL fluid for both the measurement of the chemiluminescence of AM and the differential count of cells obtained by BAL. Giemsa staining was employed as the differential count staining. Two hundred cells obtained by BAL were counted under the microscope to obtain the percents AM, lymphocytes, PMNs, and other cells. The absolute number of PMNs was calculated as follows: number of BAL cells/ml × percent PMNs = PMN number in BAL cells/ml.

Preparation of PMNs and AM.

PMNs were isolated from citrated peripheral blood specimens pooled from pairs of rats in each of the four groups by dextran sedimentation and sodium metrizoate-Ficoll (Lymphoprep; Nyegaard, Oslo, Norway) separation (10). The remaining erythrocytes were removed by hypotonic lysis. PMNs were then counted, and their concentration was adjusted to 107/ml in Krebs Ringer’s solution with 5 mM glucose. The purity and cell viability were both >97%.

BAL cells pooled from pairs of rats in each group and containing >93% AM were suspended in Krebs Ringer’s solution with 5 mM glucose and adjusted to an AM concentration of 107/ml.

Chemiluminescence.

A luminol-enhanced assay was performed with a luminometer (model 1251; LKB-Wallac, Bromma, Sweden), which was placed in an air-conditioned thermostat-controlled environment at 21 ± 1°C (10). Zymosan and luminol (5-amino-2,3-dihydro-1,4-phthalazinedione) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). A total volume of 1 ml of a mixture including 0.1 ml of PMN-AM suspension, 0.2 ml of serum-opsonized zymosan at 10 mg/ml, and 0.7 ml of luminol at a concentration of 102 μM was used. The peak chemiluminescence (in millivolts) and the time to peak were measured. The PMNs were collected from the blood, and the AMs were collected from the cells obtained by BAL.

ELISA.

Quantitation of anti-P. aeruginosa sonicate (PAO 579, O:2/5) antibodies of the immunoglobulin M (IgM), IgG, and IgA classes and of the IgG1 and IgG2a subclasses was carried out by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) as reported previously (8). The antibody concentrations expressed as ELISA units were obtained by dividing the mean optical density of the samples by the mean optical density of an internal standard expressing absorbance units between 0.30 and 0.40.

Statistical analysis.

Unpaired differences in continuous data were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney U test, and categorical data were compared with the chi-square test. The analysis of correlations between the parameters was performed by simple regression.

RESULTS

Pathology. (i) Macroscopic lung pathology.

Lung abscesses, atelectases, and fibrinous adhesion to the diaphragm or thoracic wall could be found in both ginseng group 1 and control group 1. However, the area with pathologic changes was much smaller in ginseng group 1, and the median LIMP in this group (0.06 [range, 0 to 0.27]) was significantly lower (P = 0.0003) than that in control group 1 (0.13 [range, 0 to 0.73]). In the scoring of macroscopic pathology, ginseng group 1 also showed significantly milder lung pathology (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Macroscopic pathology of rat lungs 2 weeks after intratracheal challenge with P. aeruginosa

| Treatment group (n) | No. (%) of rats with:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Score of 1 or 2 | Score of 3 | Score of 4 | |

| Ginseng 1 (40) | 16 (40.0) | 7 (17.5) | 18 (45.0)a |

| Control 1 (40) | 9 (22.5) | 3 (7.5) | 28 (70.0) |

P < 0.025 compared with the control group.

No pathologic changes were found in ginseng group 2 and control group 2.

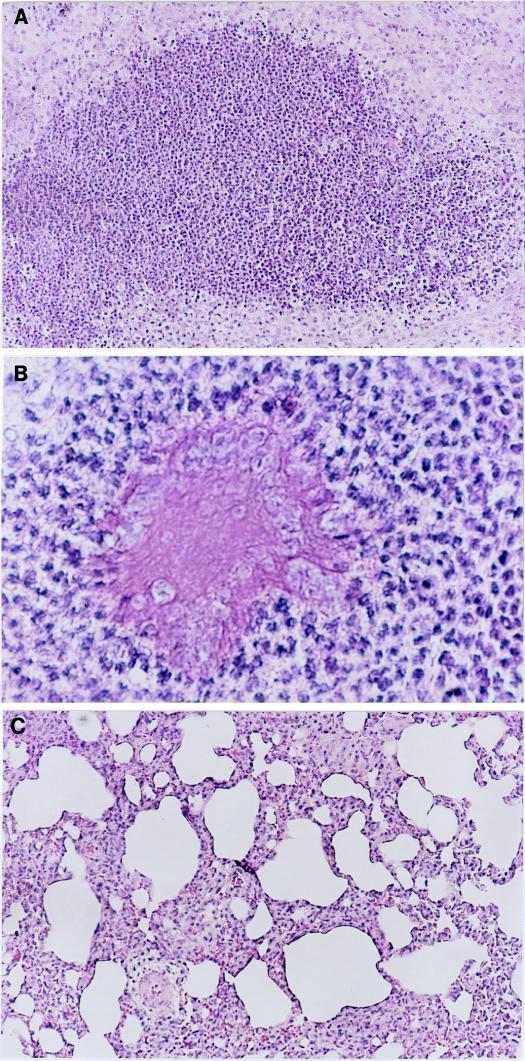

(ii) Histopathological changes in the lungs.

Control group 1 showed significant infiltration of PMNs in the lung tissues (Fig. 2A), where the alginate beads were surrounded by numerous PMNs (Fig. 2B). In ginseng group 1, the lung inflammation was much milder and the infiltration was predominantly with MNs (Fig. 2C). The area with pathologic changes in ginseng group 1 was smaller than that in control group 1. The incidence of acute inflammation in ginseng group 1 (30%) was lower than that in control group 1 (50%), but the difference was not statistically significant (Table 2).

FIG. 2.

(A) Photomicrograph of a section from the base of the left lung of a rat in the control group 2 weeks after infection with P. aeruginosa. There is significant infiltration of PMNs in the lung tissues (hematoxylin-and-eosin staining). Magnification, ×94. (B) Photomicrograph of a lung section from a rat in the control group 2 weeks after infection with P. aeruginosa. The image shows that the alginate beads are surrounded by numerous PMNs (hematoxylin-and-eosin staining). Magnification, ×375. (C) Photomicrograph of a lung section from a rat in the ginseng-treated group 2 weeks after infection with P. aeruginosa. There is mild lung inflammation with infiltration of MNs (hematoxylin-and-eosin staining). Magnification, ×94.

TABLE 2.

Microscopic pathology of rat lungs 14 days after challenge with P. aeruginosa

| Treatment group (n) | No. (%) of rats with:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute/chronic inflammation | Score of 1 or 2a | Score 3a | Score 4a | |

| Ginseng 1 (10) | 3/7 (30/70) | 3 (30) | 4 (40) | 3 (30) |

| Control 1 (10) | 5/5 (50/50) | 4 (40) | 1 (10) | 5 (50) |

For details see Materials and Methods.

Differential count of cells from BAL and PMN count in blood and cells from BAL.

The AM and lymphocyte counts were not significantly different in ginseng group 1 and control group 1 (Table 3). However, the percent PMNs in ginseng group 1 was significantly lower than that in control group 1 (P = 0.0006). In the correlation analysis, the percent PMNs in cells from BAL was positively correlated with the serum anti-P. aeruginosa IgG level in control group 1 (r = 0.75; P ≤ 0.02).

TABLE 3.

Differential count of cells obtained by lung lavage 2 weeks after intratracheal challenge with P. aeruginosa

| Treatment group (n) | Median (range) % of cells

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| AM | Lymphocytes | PMNs | |

| Ginseng 1 (10) | 95.5 (88–100) | 3.0 (0–12) | 0.5 (0–2)a |

| Control 1 (10) | 93.0 (79–98) | 3.5 (0–9) | 3.0 (1–12) |

Compared with control group, P = 0.0006.

For blood PMN count, no significant difference was found between the two P. aeruginosa-infected groups (the medians [ranges] were 70.5 × 105 [42.0 × 105 to 43.6 × 106] in ginseng group 1 and 10.7 × 106 [68.0 × 105 to 16.7 × 106] in control group 1), whereas the median number of PMNs detected in cells from BAL was significantly lower (P = 0.0002) in ginseng group 1 (24.5 × 103 [range, 0 to 14.2 × 104]) than in control group 1 (23.6 × 104 [range, 10.1 × 104 to 15.6 × 105]).

Chemiluminescence.

Two weeks after intratracheal challenge with P. aeruginosa in seaweed alginate beads, the peak luminol-enhanced AM chemiluminescence in ginseng group 1 (median, 3.7 mV; range, 1.0 to 6.5 mV) did not differ markedly from that in control group 1 (median, 3.3 mV; range, 2.0 to 4.8 mV). However, the peak chemiluminescence value of PMNs in ginseng group 1 (median, 9.7 mV; range, 5.0 to 21.2 mV) was significantly enhanced (P = 0.0009) compared with that in control group 1 (median, 4.1 mV; range, 1.1 to 8.2 mV). The regression analysis showed that the PMN chemiluminescence in ginseng group 1 was negatively correlated with the LIMP (r = −0.74; P ≤ 0.02).

No significant differences were found between the noninfected groups ginseng group 2 (n = 6) and control group 2 (n = 6) in both AM chemiluminescence (median [range], 0.54 mV [0.51 to 2.05 mV] and 0.57 mV [0.50 to 2.38 mV], respectively) and PMN chemiluminescence (6.84 mV [1.88 to 13.38 mV] and 3.90 mV [2.85 to 4.81 mV], respectively) after 2-week ginseng administration.

Serum antibody responses.

Fourteen days after challenge, the IgG level in ginseng group 1 was significantly lower than that in control group 1 (P < 0.05) (Table 4). The IgG level in control group 1 was positively correlated with the LIMP in the same group (r = 0.49; P ≤ 0.03). In the determination of IgG subclasses, a significantly higher IgG2a level (median [range], in ELISA units) was seen in ginseng group 1 (n = 20; 0.64 [0.04 to 1.85]) than in control group 1 (n = 20; 0.34 [0.01 to 0.70]) (P < 0.04), but ginseng group 1 had a significantly lower IgG1 level (0.00 [0 to 1.63] versus 0.16 [0 to 1.95] for control group 1) (P < 0.04). The regression test indicated a positive correlation between IgG1 response and LIMP in ginseng group 1 (r = 0.57; P = 0.008).

TABLE 4.

Levels in serum of antibodies against P. aeruginosa sonicate 2 weeks after intratracheal challenge with P. aeruginosa in alginate beads

| Treatment group (n) | Median (range) level (ELISA units) of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| IgG | IgA | IgM | |

| Ginseng 1 (20) | 1.19 (0.07–3.85)a | 1.14 (0.34–3.29) | 0.35 (0–3.50) |

| Control 1 (20) | 1.95 (0.50–4.16) | 1.50 (0.44–4.38) | 0.22 (0–1.88) |

Compared with control group 1, P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

PMNs are among the blood cells most important for the host defense against bacterial infections. However, in CF patients the infiltration of numerous PMNs in the lung tissues affected with chronic P. aeruginosa infection does not clear the bacteria effectively. Instead, the PMNs become an important cause of tissue damage of the lung parenchyma because of the release of lysosomal enzymes, particularly leukocyte elastase (3). It has been proved that the extracellular products of P. aeruginosa, alkaline protease and elastase, can inhibit the myeloperoxidase-mediated chemiluminescence which is one of the major antimicrobial systems manifested by PMNs (10). This might be among the reasons that PMN infiltration into lungs affected by CF does not eliminate the P. aeruginosa infection effectively. Another reason is the weak response of PMNs to the biofilm mode of growth of P. aeruginosa in the lungs of CF patients (4).

Previously we reported that ginseng treatment significantly reduced the bacterial load of P. aeruginosa in the lungs of normal as well as athymic rats (18, 19). In the present study, the oxidative burst response of PMNs from the ginseng-treated animals infected with P. aeruginosa was significantly greater than that of the control group. At the same time we found that the macroscopic lung pathology in the ginseng-treated group was significantly milder and the percent PMNs in cells obtained by BAL was lower than those in the control group. Regression analysis showed a negative correlation between the blood PMN chemiluminescence and the LIMP in the P. aeruginosa-infected rats given ginseng treatment, suggesting that greater PMN chemiluminescence leads to milder lung pathology. However, ginseng treatment could not induce any substantial PMN chemiluminescence response in noninfected rats (ginseng group 2). These results suggest that ginseng treatment of P. aeruginosa-infected animals induced an enhanced oxidative burst response which might aid in clearing the bacterial infection effectively. The activation of PMN observed in the present study could be connected to the milder macroscopic lung pathology and the reduced bacterial load we have reported previously (18, 19). From the results of histopathology we found that in 70% of the rats in the ginseng-treated group the lung inflammation had changed from an acute phase to a chronic phase, which would have reduced the damage to lung tissues from PMN proteases, whereas in the control group, 50% of the rats still had acute lung inflammation.

The study of serum anti-P. aeruginosa sonicate antibody responses showed a significantly lower IgG level with a decrease in IgG1 level (a correlate of Th-2 response) and an increase in IgG2a level (a correlate of Th-1 response) in the ginseng-treated group compared with the control group. These results are consistent with our previous findings (18), suggesting modulation of the immune response, i.e., a change from a Th-2 response (higher IgG and IgG1 levels but lower IgG2a level, as seen in the control group) to a Th-1 response (lower IgG and IgG1 levels but higher IgG2a level, as observed in the ginseng-treated group). Furthermore, in the control group, the serum IgG level was positively correlated with the LIMP and the percent PMNs in cells obtained by BAL, and in the ginseng-treated group, the serum IgG1 level was positively correlated with the LIMP. These findings suggest that greater serum IgG and IgG1 responses can be associated with more severe lung pathology.

High titers of antibodies, especially IgG, against P. aeruginosa are characteristic of chronic P. aeruginosa lung infection in CF patients (3). High levels of serum antibodies lead to formation of a large amount of immune complexes in the respiratory tract, resulting in activation of complement and the attraction of PMNs to the lung foci. The outcome of this is a type III hypersensitivity reaction which results in damage to the lung. The results of the present study showed that ginseng treatment down-regulated IgG level, thereby probably reducing the formation of immune complexes and subsequently reducing the infiltration of PMNs into the lung foci. Furthermore, ginseng treatment increased PMN chemiluminescence, which might aid in the elimination of P. aeruginosa by PMNs. Hu and colleagues (5) found that PMNs incubated with ginseng in vitro could enhance the oxidative and phagocytic activities. Our results indicate that ginseng treatment can activate PMN chemiluminescence in vivo as well. A recent in vitro investigation of ginseng showed that ginseng could significantly enhance NK activity as well as the antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity of peripheral blood MNs from both healthy subjects and patients with chronic fatigue syndrome or AIDS (17). We speculate that the activated NK cells and the antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity function might also be involved in the mechanism of ginseng’s favorable action observed in our study.

In the present study, ginseng treatment increased the PMN chemiluminescence in the rats with P. aeruginosa infection, but it did not affect the rats without infection. This might be associated with the infection process. In our rat model, the animals were infected with a gram-negative bacterium containing a large amount of an endotoxin which has been shown to prime PMNs for enhanced oxidative burst response (9, 11). It is likely that ginseng activates the endotoxin-primed neutrophils, and this might be why ginseng does not enhance the chemiluminescence of non-P. aeruginosa-infected animals.

The activation of PMNs and down-regulation of the IgG response, including the change from high IgG1 level to high IgG2a level, observed in the present study might be associated with some changes in the production of cytokines. It is well known that the production of IgG1 is induced by interleukin 4 (IL-4), the major cytokine of the Th-2 response, and that the generation of IgG2a is activated by gamma interferon, which is the main cytokine involved in the Th-1 response (13). The activation of PMNs is associated with the cytokines IL-8, IL-2, tumor necrosis factors alpha and beta, and gamma interferon (14). Therefore, the investigation of the role of ginseng in the regulation of the cytokine response is warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The expert technical assistance of Hanne Tamstorf, Jette Petersen, and Margit Bæksted is greatly acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Govan J R W, Deretic V. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:539–574. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.3.539-574.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grimwood K, To M, Rabin H R, Woods D E. Inhibition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme expression by subinhibitory antibiotic concentrations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:41–47. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Høiby N. Microbiology of cystic fibrosis. In: Hodson M E, Geddes D M, editors. Cystic fibrosis. London, England: Chapman & Hall; 1995. pp. 75–98. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Høiby N, Fomsgaard A, Jensen E T, Johansen H K, Kronborg G, Pedersen S S, Pressler T, Kharazmi A. The immune response to bacterial biofilms. In: Lappin-Scott H M, Costerton J W, editors. Microbial biofilms. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 1995. pp. 233–250. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu S, Concha C, Cooray R, Holmberg O. Ginseng-enhanced oxidative and phagocytic activities of polymorphonuclear leukocytes from bovine peripheral blood and stripping milk. Vet Res. 1995;26:155–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang K C. The pharmacology of Chinese herbs. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1993. pp. 21–45. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johansen H K, Espersen F, Cryz S J, Jr, Hougen H P, Fomsgaard A, Rygaard J, Høiby N. Immunization with Pseudomonas aeruginosa vaccines and adjuvant can modulate the type of inflammatory response subsequent to infection. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3146–3155. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.8.3146-3155.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johansen H K, Espersen F, Pedersen S S, Hougen H P, Rygaard J, Høiby N. Chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection in normal and athymic rats. APMIS. 1993;101:207–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kharazmi A, Fomsgaard A, Conrad R S, Galanos C, Høiby N. Relationship between chemical composition and biological function of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipopolysaccharide: effect on human neutrophil chemotaxis and oxidative burst. J Leukoc Biol. 1991;49:15–20. doi: 10.1002/jlb.49.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kharazmi A, Høiby N, Döring G, Valerius N H. Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoproteases inhibit human neutrophil chemiluminescence. Infect Immun. 1984;44:587–591. doi: 10.1128/iai.44.3.587-591.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kharazmi A, Rechnitzer C, Schiøtz P O, Jensen T, Baek L, Høiby N. Priming of neutrophils for enhanced oxidative burst response by sputum from cystic fibrosis patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Eur J Clin Investig. 1987;17:256. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1987.tb01245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lange K H W, Hougen H P, Høiby N, Fomsgaard A, Rygaard J, Johansen H K. Experimental chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection in rats. Non-specific stimulation with LPS reduces lethality as efficiently as specific immunization. APMIS. 1995;103:367–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawrence R A, Allen J E, Gregory W F, Kopf M, Maizels R M. Infection of IL-4-deficient mice with the parasitic nematode Brugia malayi demonstrates that host resistance is not dependent on a T helper 2-dominated immune response. J Immunol. 1995;154:5995–6001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu J H, Djeu J Y. Role of cytokines in neutrophil functions. In: Aggarwal B B, Puri R K, editors. Human cytokines: their role in disease and therapy. Cambridge, Mass: Blackwell Science, Inc.; 1995. pp. 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedersen S S, Kharazmi A, Espersen F, Høiby N. Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate in cystic fibrosis sputum and the inflammatory response. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3363–3368. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.10.3363-3368.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pedersen S S, Shand G H, Hansen B L, Hansen G N. Induction of experimental chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infection with P. aeruginosa entrapped in alginate microspheres. APMIS. 1990;98:203–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.See D M, Broumand N, Sahl L, Tilles J G. In vitro effects of echinacea and ginseng on natural killer and antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity in healthy subjects and chronic fatigue syndrome or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome patients. Immunopharmacology. 1997;35:229–235. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(96)00125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song Z J, Johansen H K, Faber V, Moser C, Kharazmi A, Rygaard J, Høiby N. Ginseng treatment reduces bacterial load and lung pathology in chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia in rats. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:961–964. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song Z J, Johansen H K, Faber V, Høiby N. Ginseng treatment enhances bacterial clearance and decreases lung pathology in athymic rats with chronic P. aeruginosa pneumonia. APMIS. 1997;105:438–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]