Abstract

Objective:

To determine whether low levels of 25−hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) contribute to the increased risk of postpartum multiple sclerosis (MS) relapses.

Design:

Prospective cohort study.

Setting:

Outpatients identified through membership rec− ords of Kaiser Permanente Northern California or Stanford University outpatient neurology clinics.

Patients:

Twenty-eight pregnant women with MS.

Interventions:

We prospectively followed up patients through the postpartum year and assessed exposures and symptoms through structured interviews. Total serum 25(OH)D levels were measured using the DiaSorin Liaison Assay during the third trimester and 2, 4, and 6 months after giving birth. The data were analyzed using longitudinal multivariable methods.

Main Outcome Measures:

Levels of 25(OH)D and re-lapse rate.

Results:

Fourteen (50%) women breastfed exclusively, and 12 women (43%) relapsed within 6 months after giving birth. During pregnancy, the average 25(OH)D levels were25.4 ng/mL (range, 13.7–42.6) and were affected only by season (P=.009). In contrast, in the postpartum period, 25 (OH)D levels were significantly affected by breastfeeding and relapse status. Levels of 25(OH)D remained low in the exclusive breastfeeding group, yet rose significantly in the nonexclusive breastfeeding group regardless of season (P=.007, unadjusted; P=.02, adjusted for season). By 4 and 6 months after childbirth, 25(OH)D levels were, on average, 5 ng/mL lower in the women who breastfed exclusively compared with the nonbreastfeeding group (P=.001).

Conclusions:

Pregnancy and exclusive breastfeeding are strongly associated with low 25(OH)D levels in women with MS. However, these lower vitamin D levels were not associated with an increased risk of postpartum MS relapses. These data suggest that low vitamin D in isolation is not an important risk factor for postpartum MS relapses.

DURING THE LAST DECADE, low level of vitamin D, a potent immunomodulator, has emerged as an important risk factor for multiple sclerosis (MS) as well as other autoimmune diseases and certain cancers. These findings have generated enthusiasm among scientists and policy makers with the hope that increasing the amount of vitamin D supplementation will have broad public health benefits.

The objective of this study was to examine the role of vitamin D levels during pregnancy and lactation and the risk of postpartum MS relapses. Several groups have reported that low serum vitamin D levels may increase the risk of relapses in nonpregnant patients with MS.1–3 The observation that healthy pregnant and lactating women are at particularly high risk of vitamin D insufficiency, regardless of race,4,5 suggests that pregnant and nursing mothers with MS may have a higher risk of relapses. However, it has already been well established that the risk of MS relapse decreases during pregnancy and increases in the postpartum period6,7 and that breastfeeding does not increase the risk of relapses.6–8 Thus, studying the role of vitamin D on postpartum relapses presents a unique opportunity to deepen our understanding of the relationship between vitamin D and MS pathophysiology.

METHODS

SUBJECTS AND STUDY DESIGN

Details of the subject recruitment and study design have previously been described.8,9 Briefly, we recruited 32 pregnant women with clinically definite MS from Northern California between 2002 and 2005. Details of the study and testing procedures were explained to each subject, and written informed consent was obtained. The institutional review boards at Stanford University and Kaiser Foundation Research Institute approved this study.

Subjects donated blood and completed structured interviewer-administered questionnaires at study entry, during the remaining trimesters of pregnancy, and at 2, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after childbirth. Relapses were defined according to standard criteria8 and were confirmed by the treating physician.

Levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) were measured using the Food and Drug Administration–approved direct, competitive chemiluminescence immunoassay DiaSorin LIAISON platform1 performed at Heartland Assays Inc (Ames, Iowa).10 Serum samples obtained during the third trimester and 2, 4, and 6 months after childbirth were stored at −80°C and were analyzed for all subjects who had at least 1 pregnancy and 1 postpartum sample available (n=28). Very few samples were missing, and 94% (105 of 112) of samples from 28 women were included in the analysis.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The data were analyzed using longitudinal data methods aimed at identifying patterns over time while accounting for interindividual and intraindividual variation. To determine whether 25(OH)D levels change during pregnancy and the postpartum period (or in relation to the onset of relapse symptoms), piece- wise linear mixed models were used. The models were hypothesis driven and included 25(OH)D in nanograms per milliliter as the dependent variable and time in days relative to the day of delivery (or onset of relapse symptoms), relapse within the first 6 months after childbirth (yes/no), exclusive breastfeeding (yes/no), and season of blood draw (April-September vs October-March) as the independent variables. Exclusive breast- feeding was defined as no regular formula feedings for the first 2 months after childbirth.8 To identify breakpoints in the data, a nonparametric method for estimating local regression (loess) of changes in serum 25(OH)D over time was used.9

The means (standard deviations [SD]) of normally distributed variables were compared using 2-sample t tests; for variables with nonparametric distributions, the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used. Binary or categorical variables were analyzed using X2 with Fisher exact test. To adjust for multiple comparisons, [H9251] was set at .01. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9 (Cary, North Carolina).

To graphically depict the differences in absolute and relative values of immunological parameters, we compared the mean (SD) of 25(OH)D at each time point between women with MS (with and without relapses within the first 4 months after child- birth) and healthy pregnant women.

RESULTS

Detailed demographic and clinical characteristics of participants have been previously described.8,9 Briefly, most participants (93%) were white, all but 1 took prenatal vitamins during pregnancy, 14 (50%) breastfed exclusively, and 17 (71%) relapsed within 12 months after childbirth, most of whom (n=12) relapsed within 6 months. Additional baseline and clinical characteristics of women with MS who breastfed exclusively for at least the first 2 months and those who did not breastfeed are presented in the Table.

Table.

Characteristics of Study Participants at Onset of Pregnancy, During Pregnancy, and in the Postpartum Period

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Exclusive Breastfeeding (n=14) |

Nonexclusive Breastfeeding (n=14) |

|

| Age, y, mean (SD)a | 33.0 (3.5) | 32.2 (4.5) |

| Disease duration, y, median (range)a | 4.6 (1.6–20.8) | 6.2 (2.1–15.8) |

| White race | 13 (93) | 13 (93) |

| Samples obtained during summer | ||

| Third trimester | 7 (50) | 8 (57) |

| 6 mo after childbirth | 5 (36) | 5 (36) |

| Prenatal vitamin use | ||

| Third trimester | 14 (100) | 13 (93) |

| After childbirth | ||

| 0–2 mo | 3 (21) | 4 (29) |

| ≥6 mo | 7(50) | 7(50) |

| Women with relapses after childbirth | 5 (36) | 12 (86) |

| 0–1 mo | 1 (7) | 4 (29) |

| 2–3 mo | 1 (7) | 4 (29) |

| 4–5 mo | 0 | 2 (14) |

| ≥6 mo | 3 (21) | 2 (14) |

At onset of pregnancy.

Pregnancy and exclusive breastfeeding were strongly associated with low 25(OH)D levels (Figure 1). During pregnancy, 20 women (71%) were vitamin D insufficient ([H11021]30 ng/mL [to convert to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 2.496]) and the average 25(OH)D levels were 25.4 ng/mL (range, 13.−42.6). In the postpartum period, 25(OH)D levels remained low among the exclusive breastfeeding group yet rose significantly in the non- exclusive breastfeeding group (Figure 1; P = .007, unadjusted; P=.02, adjusted for season; for rise from pregnancy to 4 months after childbirth). By 4 and 6 months after childbirth, 25(OH)D levels were an average of 5 ng/mL lower in the women who breastfed exclusively compared with the nonbreastfeeding group (Figure 1; P=.001 unadjusted; P=.38 adjusted for season). Of the women who breastfed exclusively, most (n=10; 71%) were still vitamin D insufficient compared with 6 (43%) who breastfed little or not at all, although this did not reach statistical significance (P=.25, 2-sided Fisher exact test).

Figure 1.

Serum 25(OH)D levels during pregnancy and exclusive breastfeeding in women with multiple sclerosis. Depicted are the mean (standard deviation) of serum 25(OH)D levels in women with multiple sclerosis who breastfed exclusively for at least 2 months (BF, n=14) and those who did not (NBF, n=14) during the third trimester of pregnancy and the postpartum period. *P<.001, unadjusted; P=.02, adjusted for season; †P=.001 unadjusted; P=.04, adjusted for season. To convert 25(OH)D to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 2.496.

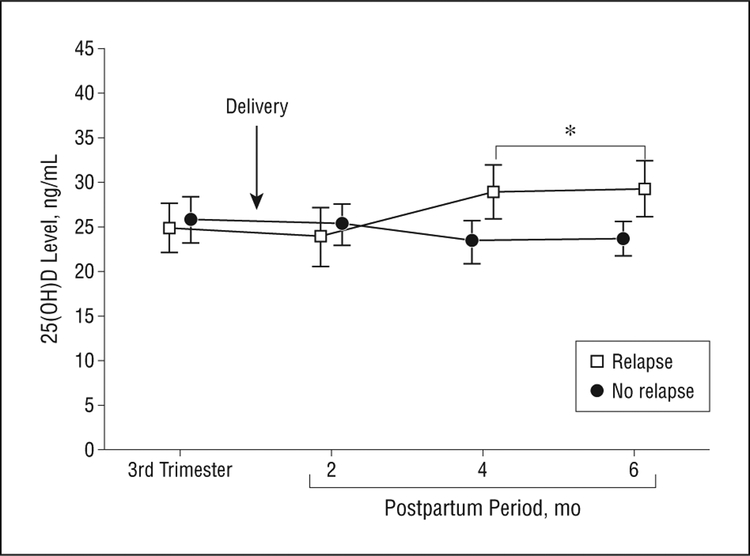

In contrast, postpartum MS relapses were not associated with low 25(OH)D (Figure 2 and Figure 3). If anything, by 3 to 6 months after childbirth, 25(OH)D levels were marginally higher among the women who relapsed within the first 6 months after childbirth compared with women who were relapse-free during the corresponding period (Figure 2; P=.04 unadjusted; P=.04 adjusted for season). In women with postpartum re- lapses, 25(OH)D levels rose an average of 4 ng/mL around the time of relapse (Figure 3; P=.02, unadjusted; P=.005, adjusted for season).

Figure 2.

Mean (standard deviation) serum 25(OH)D levels in women who had postpartum multiple sclerosis relapses (n=12) and women with multiple sclerosis who were relapse-free during pregnancy and the first 6 months after childbirth (n=16) during the third trimester of pregnancy and the postpartum period. *P=.04, unadjusted; P=.04, adjusted for season. To convert 25(OH)D to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 2.496.

Figure 3.

Serum 25(OH)D levels and onset of postpartum multiple sclerosis relapse symptoms. The horizontal line indicates represents the midpoint of that category (eg, 50 days encompasses values from days 1–100). For women who relapsed more than once, this represents the first relapse. The y-axis represents the change in serum 25(OH)D levels relative to each individual’s cross-study mean (horizontal line). Mean (standard deviation) are depicted at each time point. Only values from women who relapsed during the first 6 months after childbirth are included (n=12). The perirelapse rise in the 25(OH)D level approximately 50 days after the onset of relapse symptoms illustrated is highly significant (P=.005, adjusted for season, by repeated measures linear mixed model). However, this rise does not clearly precede the onset of relapse symptoms, suggesting that it is not causally related to postpartum MS relapses. To convert 25(OH)D to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 2.496.

COMMENT

In this prospective cohort study, we found that women with MS had low vitamin D levels during pregnancy and lactation but that these lower levels were not associated with an increased risk of relapses. We found that vitamin D levels rose around the time of relapse and were higher 3 to 6 months after childbirth in women who relapsed. These findings suggest that low vitamin D in isolation is not an important predictor of postpartum MS relapses and imply that other factors associated with pregnancy and lactation may be important modulators of the relationship between vitamin D and MS disease activity.

We do not believe that higher vitamin D levels increase the risk of postpartum relapses, as the rise we observed did not appear to occur prior to the onset of symptoms and the findings were of marginal statistical significance after accounting for season. Instead, we think this apparent inverse association is a reflection of the fact that most of the women who relapsed in this study also did not breastfeed or did so only briefly.8

On the surface, our finding that low vitamin D is not an important risk factor for postpartum MS relapses, thereby implying that vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy and lactation is unlikely to affect the risk of postpartum MS relapses, may seem inconsistent with studies that found an association between low serum vitamin D and MS relapses1–3 and MS disability.11–13 However, our findings seem logical when other lines of evidence are considered. First, it is well known that women who are pregnant or lactating are at high risk of hypovitaminosis D.4 Second, it is also well established that pregnant women with MS have a low risk of relapse and that lactation does not increase the risk of relapses.6,7 Third, there is no evidence that the hormonal effects of pregnancy or lactation are different in women with MS compared with healthy women. Finally, dark-skinned individuals are at higher risk of vitamin D insufficiency,14 yet have a lower risk of MS than white individuals,15 indicating that low vitamin D in isolation is not always associated with increased risk of MS.

We speculate that the most likely explanation for our apparently paradoxical finding (low vitamin D does not increase the risk of postpartum relapse) is that a factors associated with pregnancy and lactation modulates and perhaps overrides the proinflammatory effects of low vitamin D. That immunomodulatory interactions between vitamin D and sex hormones and/or female sex might exist is supported by data showing that vitamin D alters prognosis in the animal model of MS only in female mice16 and by in vitro studies showing that vitamin D and progesterone enhance inactivation of estradiol in monocytes through regulation of key estrogen metabolizing enzymes.17

Our study is limited by the small sample and inability to account for sun exposure, though we accounted for most factors that influence serum vitamin D levels (eg, race/ethnicity, season, and prenatal vitamin use). In addition, because most of the women in our study were vitamin D insufficient, we cannot exclude the possibility that much higher 25(OH)D levels may be protective. Thus, our findings should be confirmed in a larger study.

Our finding that low vitamin D is not a risk factor for MS relapses in pregnant and lactating women suggests that increasing vitamin D levels during pregnancy and the postpartum period in women with MS is unlikely to affect the risk of postpartum relapses. Therefore, our findings imply that the recommended dose of vitamin D supplementation for women with MS during pregnancy and lactation should be the same as for women who are not. Our results suggest that future studies aimed at identifying and unraveling the relationship between vitamin D, pregnancy/lactation-related hormones, and regulation of MS inflammation may reveal novel insights into MS pathophysiology.

Funding/Support:

This study was supported by K23 grant NS43207 from the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health and a Wadsworth Foundation Young Investigator’s Award (Dr Langer-Gould).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tremlett H, van der Mei IA, Pittas F, et al. Monthly ambient sunlight, infections and relapse rates in multiple sclerosis. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;31(4):271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mowry EM, Krupp LB, Milazzo M, et al. Vitamin D status is associated with relapse rate in pediatric-onset multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2010;67(5):618–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soilu-Hänninen M, Laaksonen M, Laitinen I, Erälinna JP, Lilius EM, Mononen I. A longitudinal study of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and intact parathyroid hormone levels indicate the importance of vitamin D and calcium homeostasis regulation in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(2):152–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hollis BW, Wagner CL. Vitamin D requirements during lactation: high-dose maternal supplementation as therapy to prevent hypovitaminosis D for both the mother and the nursing infant. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(6)(suppl):1752S–1758S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hollis BW, Wagner CL. Assessment of dietary vitamin D requirements during pregnancy and lactation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(5):717–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson LM, Franklin GM, Jones MC. Risk of multiple sclerosis exacerbation during pregnancy and breast-feeding. JAMA. 1988;259(23):3441–3443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Confavreux C, Hutchinson M, Hours MM, Cortinovis-Tourniaire P, Moreau T; Pregnancy in Multiple Sclerosis Group. Rate of pregnancy-related relapse in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(5):285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langer-Gould A, Huang SM, Gupta R, et al. Exclusive breastfeeding and the risk of postpartum relapses in women with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2009; 66(8):958–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langer-Gould A, Gupta R, Huang S, et al. Interferon-gamma-producing T cells, pregnancy, and postpartum relapses of multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2010; 67(1):51–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ersfeld DL, Rao DS, Body JJ, et al. Analytical and clinical validation of the 25 OH vitamin D assay for the LIAISON automated analyzer. Clin Biochem. 2004;37(10):867–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smolders J, Menheere P, Kessels A, Damoiseaux J, Hupperts R. Association of vitamin D metabolite levels with relapse rate and disability in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2008;14(9):1220–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kragt J, van Amerongen B, Killestein J, et al. Higher levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D are associated with a lower incidence of multiple sclerosis only in women. Mult Scler. 2009;15(1):9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soilu-Hänninen M, Airas L, Mononen I, Heikkilä A, Viljanen M, Hänninen A. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D levels in serum at the onset of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005;11(3):266–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holick MF, Vitamin D. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(3):266–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurtzke JF, Page WF. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in US veterans VII: risk factors for MS. Neurology. 1997;48(1):204–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spach KM, Hayes CE. Vitamin D3 confers protection from autoimmune encephalomyelitis only in female mice. J Immunol. 2005;175(6):4119–4126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mountford JC, Bunce CM, Hughes SV, et al. Estrone potentiates myeloid cell differentiation: a role for 17 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in modulating hemopoiesis. Exp Hematol. 1999;27(3):451–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]