Abstract

An increasing number of individuals are reporting increased stress and anxiety associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. A feasibility, mixed-method design was conducted to investigate distant Reiki as a virtual healing modality within Rogers' framework of the Science of Unitary Human Beings. Data were collected using pre- and post-distant Reiki session interviews and 2 surveys. Study findings demonstrated changes in participant pattern manifestation and statistically significant reductions in perceived stress and anxiety (P < .001). The preliminary findings support the feasibility of distant Reiki and suggest that nurses, who are Reiki practitioners, may influence the human-environmental field to foster healing.

Keywords: anxiety, complementary therapies, COVID-19, distant Reiki, Martha Rogers, Science of Unitary Human Beings, stress

AS THE CORONAVIRUS disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic continues to alter daily living, mental health issues are an increasing concern.1,2 Many individuals are reporting increased levels of stress,2,3 anxiety,4–6 and low affect,2 which is largely attributed to social distancing guidelines1,7 and the lack of access to socially distant self-care tools.8 Therefore, it is important to increase the availability of complementary self-care healing modalities to individuals in a socially distant way, within the comfort of the person's own home.

Complementary healing therapies have been recognized as important therapeutic modalities. One such complementary practice is Reiki, which can be offered both hands on and distantly. Reiki is a holistic healing modality that enables the nurse to participate in universal life force energy exchange9 to promote wellness in recipients. Reiki is offered by practitioners, including nurses, who are trained or “attuned” to Reiki, to perceive energy manifestations in recipients. A theoretical perspective developed by Martha Rogers, the Science of Unitary Human Beings (SUHB), provides a lens for investigating different healing energy field manifestations, which includes Reiki.10 Rogerian science views the person as whole within the human-environmental energy field. The nurse-patient relationship creates opportunities for a dynamic “pattern appreciation”11 in the human environmental field through the intentional presence of the nurse. Although there is scant literature exploring Reiki and Rogerian science,12 the philosophical assumptions of the human-environmental field in Rogers' SUHB provide a theoretical lens to better understand Reiki as a therapeutic nursing technique to access the energy field and aid in generating new patterns. The purpose of this study is to explore the use of distant Reiki as a healing modality within the human environmental field pattern.

Statements of Significance

What is known or assumed to be true about this topic?

Martha Rogers' framework posits the person as a “unitary whole,” in separate from their environment.

Rogers viewed the nurse-patient relationship as a dynamic exchange through intentional presence from the nurse that may promote healing.

Nursing can use distant healing to engage in mutual process to promote new patterns.

What the article adds:

The terms “stress” and “anxiety” were reconceptualized as manifestations of “perceived stress” and “perceived anxiety” to align with Rogers' SUHB framework.

Although prior Reiki literature has referenced Rogers' SUHB framework, this study is novel by fully analyzing and interpreting the mixed-method results through Rogerian science.

During the pandemic, a nurse-administered distant Reiki intervention may help promote awareness, self-reflection, self-discovery, and human choice.

STRESS AND ANXIETY

Psychological stress is a common and debilitating symptom experienced by many individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic.3 Elevated cortisol levels have been found in individuals who experienced high amounts of stress,13 and the literature reports an increase in cortisol in the public with or without COVID-19 that correlated highly with anxiety.14

Anxiety is described by many health providers as another response experienced in some individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic.4–6 In recent investigations, participants reported experiencing increased levels of anxiety, which researchers attributed to fear, long periods of isolation during the quarantine, and inability to exercise.1,7 Other studies have shown a significant gender difference and reports of anxiety, with females experiencing higher levels of anxiety compared to males.6,15

The psychological implications were experienced by many individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. The problem was enhanced by reduced access to healing resources, health care providers, and self-care tools, which helped the stimulus for nurse-driven interventions and complementary therapies to be delivered to individuals using a virtual platform. Access to an inexpensive, complementary, and stress-reducing distant healing modality, such as distant Reiki, within the SUHB framework, may help generate new awareness about perceived stressful experiences, promote new pattern appreciation and awareness of the pandimensional universe, and provide an avenue of selfcare in the presence of one's own home environment. This study explores the use of nurse-delivered distant Reiki as a healing therapy during a time of social distancing during a time of social distancing and when stress and anxiety are prevalent.

STUDY AIMS

The study aimed to explore: (1) if it is feasible to recruit and retain participants (through expressions of human choice) to participate in a study composed of 2 distant Reiki administrations on a virtual platform; (2) the participant's reflections on their virtual distant Reiki experience within the human environmental field pattern of their home environment as a healing space; and (3) the preliminary pattern appreciation of distant Reiki on the human pattern of the whole as manifested by participant response in perceived stress and anxiety.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Martha Rogers' SUHB provides a framework to understand the Reiki experience for individuals living through the COVID-19 pandemic. According to Rogers, humans were energy-based beings inseparable from their environments.16 In her early writings, Rogers described the significant intereffect between human and environmental energy fields, and the nurse-patient relationship.17 She posited that this effect occurs through human pandimensionality, the “non-linear domain without spatial or temporal attributes10” and the vast amount of energy from the nurse to the environment.18 Through pandimensonality, Rogers discovered it was possible for a change in pattern to occur when accessing the natural occurrences in the pandimensional universe through integrality when one participates in self-awareness and intentionality.18,19 This phenomenon prompts further research in distance healing and other “energy field manifestations” through accessing the human-environmental energy field, like distant Reiki.19 By the recipient and nurse actively engaging in mutual processes and intention, it brings a greater sense of self-awareness and awareness of the other; thereby using one's “cognition,” “tacit knowing,” and “intuition” to create new patterns.19

Rogers further proposed that nursing science is grounded in knowing the “person as a whole,” and that nurses are engaged in an inseparable and dynamic mutual process that uses the human-environmental field pattern.10 Distant Reiki is a form of energy field manifestation that the nurse can use to promote pattern appreciation and generate a new pattern of the whole.

Reiki and Rogerian science

The principles of distant Reiki strongly resonate with the assumptions and principles that underlie Rogerian science and the SUHB framework. To date, much of the literature describing Reiki is grounded in Rogerian science.20–22 Several qualitative studies have linked these concepts more fully,23 especially by Ring and her assessment of the unitary field pattern after participants received Reiki.24

Rogers' SUHB provides a link between the assumptions and principles of nursing and Reiki. Awareness, mindfulness, and integral presence of the nurse25 create a dynamic and simultaneous awareness of one's pattern between the person receiving Reiki and the provider. A holistic, humanistic pattern appreciation is created and manifests itself in the change of feelings from the nurse engaging in mutual process with the recipient's energy field through pandimensionality. Phillips25 has proposed that the nurse-patient interaction can lead to wellbecoming, which encourages the participation and transcending of the “energyspirit” of the other. The findings from this study advance our understanding of how nursing can integrate virtual modalities to promote one's healing choice and pattern manifestation through creating healing spaces and using a self-care modality in their home.

METHODOLOGY

Research design

This mixed-methods feasibility study incorporated a single group of participants with pre- and post-analysis and qualitative exploration of participants' experience and manifestations of change within their human-environmental field patterning. Manifestations of perceived stress, manifestations of perceived anxiety, and participant experience were evaluated pre- and post-distant Reiki sessions consisting of two 30-minute administrations 24 to 36 hours apart. The study was composed of 2 separate distant Reiki administrations based on recommendations in current Reiki literature.26

The principal investigator (PI), a certified Reiki Master Teacher and nurse, administered the distant Reiki. A pre-distant Reiki session script was read by the PI to explain distant Reiki and what the participant could expect related to the delivery of distant Reiki. The PI followed a standard Reiki method of “meditating presence” that permits energy to move to where it needs to be in the recipient's body.22 Then, a continuous 30-minute distant Reiki session is provided through an intentional creation of a ball of energy with the PI's hands. Meanwhile, the PI also generated positive thoughts and intentions directed towards the participant as distant Reiki flowed.

Participant experiences were evaluated using pre- and post-qualitative description, a distant Reiki interview session, and instrument measurements of perceived anxiety and stress. Perceived anxiety was measured using the 20-item State Trait Anxiety Inventory Form Y-1 (STAI), which is a reliable tool with a Cronbach's α of 0.87.27 Perceived stress was measured by the Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R) tool, which is reliable and valid, with a high intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for posttraumatic stress symptoms (Cronbach's α = 0.79-0.94)28,29 and test-retest reliability (0.89-0.94).29

The PI maintained intervention fidelity by utilizing subject receipt that is having the participant recite the understanding of the distant Reiki back to the PI following their verbal consent to participate in the study. Credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability were ensured through triangulation of data, member checks, thick, rich description, audit trails, and having committee members review and debrief about the data obtained, which promoted qualitative trustworthiness. A reflexivity journal was kept by the PI, noting any thoughts, feelings, and reflections on the delivery of distant Reiki to enhance the quality of the study and reduce bias. A reflexivity journal is important in mixed-method research by ensuring the position of the researcher who is delivering Reiki and experiencing the study's impact on themselves and participants. Approval was received from the university's institutional review board.

Sample

The participant sample (n = 25) included individuals who perceived experiencing feelings of stress and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Recruitment of study participants both with and without exposure to Reiki experiences was achieved through sharing a flier on the PI's Facebook page and by posting the flier on the “PH Nurse Explains” page, which focused on COVID-19-related information. Individuals interested in participating in the study were asked to contact the PI through a phone number or email, although some participants opted to use Facebook Messenger. Inclusion criteria were defined as being 18 years or older, living in the 50 United States, having access to the Zoom conferencing system, and being able to speak and write in English. Exclusion criteria included pregnant women, adults unable to provide consent, prisoners, and individuals who did not speak in English, or do not live in the United States. Verbal consent was obtained by the PI during enrollment. Participants received a $25 Bank of America gift card at the study's cessation.

Setting

The study was conducted in the participant's home using Zoom, a video application that allows for 2 or more people to participate in a virtual conference. One participant chose to receive the distant Reiki in their car and another from their work office. Participants selected the location where the distant Reiki session would occur and were encouraged to make any modifications to make the space comfortable. The PI offered optional suggestions to modify the environment, such as dimming the lights, increasing or decreasing the temperature, choosing a quiet location, adding a relaxing fragrance in the room, or resting in a comfortable location. Usual standards of Reiki practice provide for the inclusion of music, which typically involves soft tones without lyrics. Music was offered to the participants, and all participants opted to have music playing during the session.

PROCEDURES

Study participants were formally enrolled in the study through a 15-minute phone conversation during which time eligibility criteria were reviewed, verbal consent was obtained, and demographic information collected. The 2 dates were scheduled for participants to receive distant Reiki. Participants then met with the PI over Zoom and answered presession interview questions, verbalized their responses to the presession STAI and IES-R tools, and received one 30-minute distant Reiki session. After 24 to 36 hours, participants received another 30-minute distant Reiki session, followed by the STAI and IES-R tools and were interviewed to discuss their experience.

Data collection

An individual data file was created in REDCap for each study participant using an individual data code as an identifier to maintain participant confidentiality. Participants answered the survey data verbally with a shared screen from the PI to minimize participants having to manage a Zoom and survey screen and promote a more relaxing environment. All demographic and survey data were manually recorded by the PI on REDCap. Post-distant Reiki session interviews were recorded on a Zoom recorder and an external voice recorder, and then transcribed through a commercial service. Data were collected between June 2021 and July 2021.

Data analysis

Perceived stress and anxiety were analyzed using descriptive statistics and the paired t test. Because of the feasibility and pilot nature of this study, statistical significance value was set at P < .10. Due to the small sample size, it was decided to lessen the probability of having a type II error by increasing the statistical significance level. With the statistical power being P < .10, the sample size was 25 to reach an upper and lower CI limit (62%-92%) to be adequately powered for pilot research and account for attrition. Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen's d in IBM SPSS version 27.

The PI reviewed the qualitative transcriptions and conducted analysis through N-Vivo. Data were coded line by line from the transcript. Responses were organized under defined predetermined categories of times 1 (initial nurse-participant interaction), 2 (first Reiki administration), and 3 (the second Reiki administration). Triangulation was attained by reviewing and comparing the survey responses and interview data and noting any similarities or discrepancies, generating common pattern analysis from each interview question in N-Vivo, and reporting patterns congruent with Roger's SUHB and current Reiki literature. In the findings later, direct quotations from participants are included to illustrate results with some jargon (such as “you know”) removed to enhance clarity.

RESULTS

Sample

The final study sample was composed of 25 participants. The age of study participants ranged between 25 and 74 years (mean = 38.2; SD = 11.65). Demographic information is present in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographicsa.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (binned) | |

| 20-29 | 3 (12) |

| 30-39 | 14 (56) |

| 40-49 | 4 (16) |

| 50-59 | 3 (12) |

| 70-79 | 1 (4) |

| Location (region) | |

| New England | 20 (80) |

| Outside New England | 5 (20) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 18 (72) |

| Male | 7 (28) |

| Race | |

| White | 22 (88) |

| Asian | 2 (8) |

| Native American or Pacific Islander | 1 (4) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 (8) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 23 (92) |

| Reiki practitioner? | |

| Yes | 1 (4) |

| No | 24 (96) |

| Heard of Reiki? | |

| Yes | 22 (88) |

| No | 3 (12) |

| Heard of distant Reiki? | |

| Yes | 6 (24) |

| No | 19 (76) |

| Previous Reiki experience? | |

| Yes | 15 (60) |

| No | 10 (40) |

| Previous distant Reiki experience? | |

| Yes | 2 (8) |

| No | 23 (92) |

| Know a person who received Reiki before? | |

| Yes | 18 (72) |

| No | 7 (28) |

aNumber of participants = 25.

Aim 1

Participants elected to join the study in a timely manner, with all participants formally enrolled in 3 weeks. Many participants commented about the ease of recruitment, the ability to participate remotely, and the opportunity to receive 2 free distant Reiki sessions during a stressful time. One of the study participants could only participate in 1 of the 2 sessions due to a prior obligation and was willing to reschedule but would have been outside the protocol timeline. Their data were removed prior to data analysis. The remaining participants completed both distant Reiki sessions, and many described looking forward to the subsequent session.

There were technological and other issues that affected 2 of the participants, one who lost music during the session after 20 minutes and another who was interrupted by their spouse during their session, which they said increased their anxiety. Some participants noted that the music became too loud, but none requested it to be lowered. Other participants did not elect to make changes to their home environment to make it conducive to healing, and some participants decided to use their work or car space to receive distant Reiki. They described that their home environment was not conducive because of family members being home or due to their busy schedules.

Aims 2 and 3

There are 3 time points used to report data: time 1, time 2, and time 3.

Time 1: Initial nurse-participant encounter

The initial nurse-participant encounter involved the nurse/Reiki practitioner (RP) meeting with each participant, on Zoom, after responding to the study flier. This encounter set the foundation for creating and building rapport. During the initial meeting, participants reported having more stress and/or anxiety due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Many of their accounts described workplace stress compared with personal or home stressors. For example, one participant stated:

Just more work-related stress than anything. We never went out with the kids, so it didn't affect our personal lives. Not a lot of help, and high tension, and face-to-face with customers. And, the tension and the lack of help is not easy. Wearing a lot of hats during the COVID period.

Participant accounts support the use of distant Reiki as a stress-reducing approach for individuals with workplace stress, especially those with jobs that were negatively affected by COVID-19.

When evaluating the study participant's perceptions and reflections of their human environmental field, one major dimension was their desire to find a quiet environment, separate from other humans and pets in the home. Over 65% of participants selected to receive the distant Reiki session in their bedroom because it was the quietest, darkest, and more comfortable place in the home. Most participants also elected to make changes to their home environment to make it more conducive to healing by cleaning their space prior to the sessions, dimming the lights, and finding comfortable furniture. One participant noted:

I found that my [bed]room is my relaxing spot, I guess, by using distant Reiki. I've learned to find one space that's mine where it's not interrupted and there's a lot of flow of positive energy. Though there is a lot of flow of positive energy throughout the house anyways, but this space doesn't have any interruption of that. There's no real big furniture, there's no animals or any contact in that sense. So, the Reiki has helped me to find a space where I feel the more beneficial flow in my energy, in my body. Or to my body.

This response highlighted how participants may not have been previously aware of the degree to which their home environment or physical space may affect their well-being and self-care. The ability to choose the study space and the experience of distant Reiki brought to conscious awareness the importance of the environment in their home.

Time 2: First distant Reiki session

There were 2 types of responses to the first Reiki administration. Most participants reported feeling calm, peaceful, and relaxed after the first distant Reiki session. A common response was, “Definitely [felt] calmer and more peaceful. I just felt lighter” and “I did feel relaxed after the first session. Kind of like I had just had a 30-minute meditation, so I was very relaxed and content after the first session. Which was good, ‘cause yesterday was a little crazy.”

However, there were 3 participants who experienced sadness, which was transient, with positive feelings reported after the second distant Reiki session. The more uncomfortable feelings, such as sadness, were expressed in the first session as shown in the following quote:

So, first one, even though I was more secluded, I felt more, a heavy word ... possibly anguish in a weird way? Again, there was a mix of ... a mix of emotions. A bit frustration, a bit heavy, a lot of past stuff that you wish you could control.

During the second session, their uncomfortable response was alleviated as stated in the following sample statement: “I still felt more relaxed. No moments of sadness like last time, which I'm happy about, although milder and less intense. I didn't feel like I needed as much today compared to yesterday.” For those participants who expressed uncomfortable feelings, the nurse/RP provided supportive statements and education to let them know their feelings are an expected part of the process.

Time 3: Second distant Reiki session

Participants reported overall positive experiences after the second Reiki session. Most participants reported a sense of calm, relaxation, and lightness from when they first enrolled in the study. Other participants reported perceptions of comforting physical sensations. Some of their quotes include:

Definitely warm, tingling, very comforting presence. It was weird, at a few points I could feel a lot. I could feel almost like a lot of pressure in my throat, like severe pressure, that was being lifted out ... And then there was like a couple times where I almost felt like ... I don't know, this just sounds weird. But I was like being like hugged, you know? That was definitely awesome.

[I] think the first session I had more sensations between in the,...like [in] my muscles and this [session] I was just very calm. There wasn't any sensations or any feelings. It just felt like I was a lot calmer this time around than I was the second–the first time around. I felt very warm today.

During the second distant Reiki session, study participants reported either feeling much better than the first session or described a resolution of perceived stress or anxiety. This change is likely, or may be related to, an engagement in mutual process, integrality, and the building relationship between the nurse and the participant, which is shown in the following sample comments from participants:

I felt definitely more at ease and comfortable knowing how it was gonna work and being confident that I could just let the 30-minute experience really soak in and that everything would be okay in terms of technology. So, I would say definitely less anxiety, more at ease the second time.

I guess with the second [session], I was a little more prepared as to what it would be like, so I was able to engage myself more into knowing that I was gonna be able to relax through the whole time, and I guess I kinda just knew what to expect the second time.

There was no reported negative experience receiving distant Reiki and participants described feeling neutral or willing to try Reiki again in the future as noted in the following sample statement: “Very [interested in trying distant Reiki again]. I think it's very interesting. I would definitely want to learn more. I would be completely open to trying it again.”

The emerging focus on self-care may be facilitated and accelerated by the openness and awareness created during the distant Reiki and the nurse-participant relationship that guided the experience. In the follow-up interview, participants also noted that the nurse's encouragement to create a more healing space in their personal environment directly increased their awareness about the importance of a therapeutic personal environment in their home. Sample statements include, “[I am] definitely made aware that I need more open space in my apartment ... I want to be more mindful moving forward [to have] more space so that I can feel like I can breathe and relax.” This perception of the importance of their environment allowed participants to be more open to the pattern appreciation of space and the energy it created around their home. This openness promotes wellness and the ability to recognize their home environment, such as items or pets, that influenced their well-being.

Aim 3

Quantitative data were analyzed using IBM SPSS version 27. Data on participant perceived stress and anxiety were analyzed using paired t tests obtained during the pre- and post-distant Reiki sessions (see Table 2). There was no missing data. When measuring perceived stress with the IES-R tool, the mean results at presession when compared with postsession showed a statistically significant reduction in stress symptoms from pre- to post-distant Reiki sessions. There was a medium effect size found as indicated by the Cohen's d statistic (d = 0.41; 90% CI) pre- and post-distant Reiki session stress levels. According to test parameters, 35% of study participants were initially “of concern” for an impact on health, well-being, and posttraumatic stress disorder,30 but only 4% of participants remained “of concern” post-distant Reiki sessions. The ICC α coefficient was robust at 0.911.

Table 2. Quantitative Data.

| Measure n = 24 |

Preintervention Mean (SD) |

Postintervention Mean (SD) |

t; P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stress (IES-R) | 0.9 (0.59) | 0.38 (0.46) | t = 6.2; P < .001a |

| Anxiety (STAI) | 34.41 (8.23) | 24.29 (4.1) | t = 7.5; P < .001a |

Abbreviations: IES-R, Impact of Events Scale-Revised; STAI, State Trait Anxiety Inventory.

aP values are determined statistically significant with a P < .10.

The results from the STAI survey responses showed a statistically significant reduction in anxiety symptoms from the pre-distant Reiki session to the postsession. At baseline, 30% of study participants were found to be at a clinically significant31 anxiety level, but post-distant Reiki no scores were at a clinically significant anxiety level (0%). There was a large effect size (d = 6.6; 90% CI) in anxiety symptoms after receiving the distant Reiki sessions. The postsession Cronbach α for the STAI tool was robust at 0.815, which was lower than reported in the literature,27 although 3 items (I feel jittery, I feel frightened, and I feel upset) were automatically removed from SPSS analysis after all participants responded, “strongly disagree.”

As reported, 3 out of 24 study participants indicated transient sadness during the first distant Reiki session. A group comparison using the Fisher exact test was conducted to compare demographics in participants with the 2 types of responses to identify a potential relationship in baseline differences. There were no statistically significant baseline differences when evaluating the variables for race (P = .33), gender (P = .250), age (P = .33), and first time Reiki (P = 1.0). With 60% of the participants having experience with some form of Reiki before, there was no apparent distinction in the ability to sense, feel, and experience distant Reiki.

Personal perceptions

A key point to note is the reciprocity and mutual process of energy between study participants and the nurse/RP over the time frame of the study. The nurse/RP documented their own experiences when offering the distant Reiki and reflected on the change within themselves, both reflexively and personally. The nurse/RP expressed some concerns when their own home environment became distracting, such as animals interfering with the study or outside construction noises during the distant Reiki session, which may hinder the therapeutic space created for the study. The nurse/RP asked participants whether they heard these distractions and was relieved nobody heard or felt distracted from the nurse/RP's personal environment. The Zoom conferencing system could reduce outside noise, which provided peace of mind for the nurse/RP.

DISCUSSION

This mixed-method study explored the feasibility of recruiting and retaining participants in a distant Reiki study and their perceptions receiving the distant Reiki sessions during the COVID-19 pandemic. During the time the study was conducted, physical contact was discouraged to reduce the spread of disease32 and complementary therapies, such as distant Reiki, became more popular to potentially reduce pandemic-related stress and anxiety.33 This study highlighted the impact of isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic and found that a distant Reiki session could be an accessible way to change patterns of perceived stress and anxiety.

Currently, there is no scientific literature about the use of distant Reiki and its importance as a nursing intervention during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the study findings were comparable to other distant Reiki studies. Shore34 and Demir et al's35 study suggested that distant Reiki was an effective stress reducing intervention compared with sham Reiki or control., Other distant Reiki studies suggested the distant Reiki intervention was statistically significant in reducing heart rate and blood pressure post-surgery, which may be closely linked to physiological responses found in perceived stress and anxiety.36 However, many of the empirical approaches to Reiki studies (and in particular not distant, but hands-on Reiki or hands hovered lightly above the body) have suggested a reduction in participant perceived stress or anxiety compared with sham or control.20,22,37 The difference between this study and prior literature is the meaningfulness of studying nurse-delivered distant Reiki within Rogers' SUHB framework.

Although research has utilized Reiki from the lens of Rogerian science, discussion is necessary regarding the use of Rogers' theory in mixed-method research compared with its incorporation in other Reiki research. Butcher38 generated criteria for unitariological inquiry, which were used to help this study be as congruent with Rogerian science as possible. Some of these criteria included a focus on research that follows a priori nursing science, with the nurse serving as both the researcher and the interpreter of scheduled results.

The study results from this investigation were also interpreted as pattern manifestations of perceived stress and anxiety to reflect the change in the human-environmental field over time. There was integrality and a mutual process occurring within the relationship between the nurse/RP and the participant and a shared description and understanding of changes experienced from the participant (quotes) and the nurse/RP (reflexive journal). There was pandimensional awareness and an intuitive sensing of the Reiki energy through the mutual pattern manifestation and being open and receptive to the possibilities of distant Reiki. Lastly, purposive sampling allowed for the study to represent individuals who experienced the COVID-19 pandemic to obtain from them an understanding of the pattern of the whole.38

Results

This study investigated how nurses can integrate the SUHB framework as a lens to better understand participants' response to distant healing. By accessing quantitative data to reinforce the qualitative data findings helped reflect pattern changes of the whole and avoid implying any form of causality.39 While some scholars advocate for use of qualitative approaches only when using Rogerian theory, both Rogers and other notable scholars emphasize the possibility of its expansion to the mixed method depending on the type of question and their “conceptualization.”40,41 It is critical to note that the terms “perceived stress” and “perceived anxiety” are manifestations that can be used to designate stress and anxiety from a unitary perspective, which reconceptualize the way we view stress and anxiety.42 For example, when a discordant, dysrhythmic pattern of the human environmental field is experienced, it could be manifested as stress or anxiety. Behaviors then reflect the unique perception of the individual and their idea of what responses associated with stress and anxiety mean to them. This viewpoint precipitated how to interpret the results of the study.

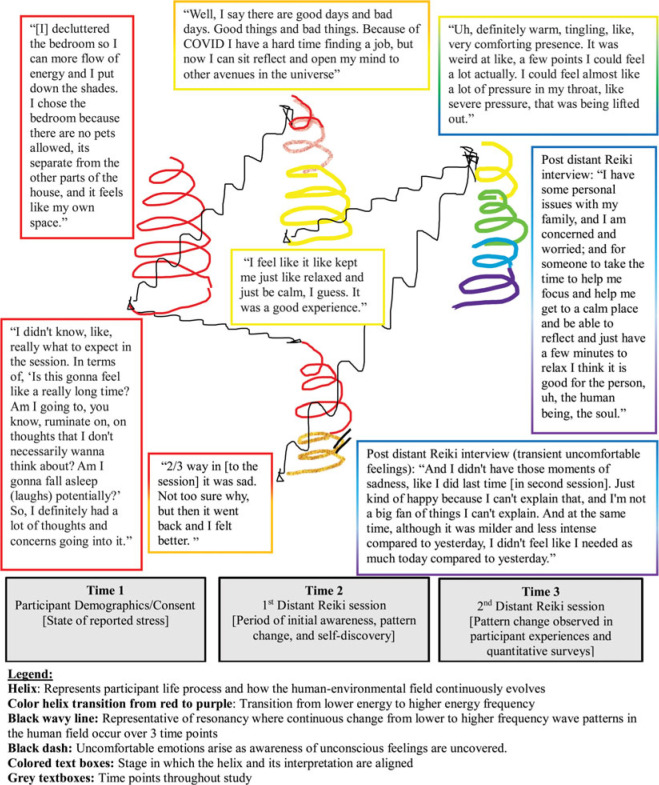

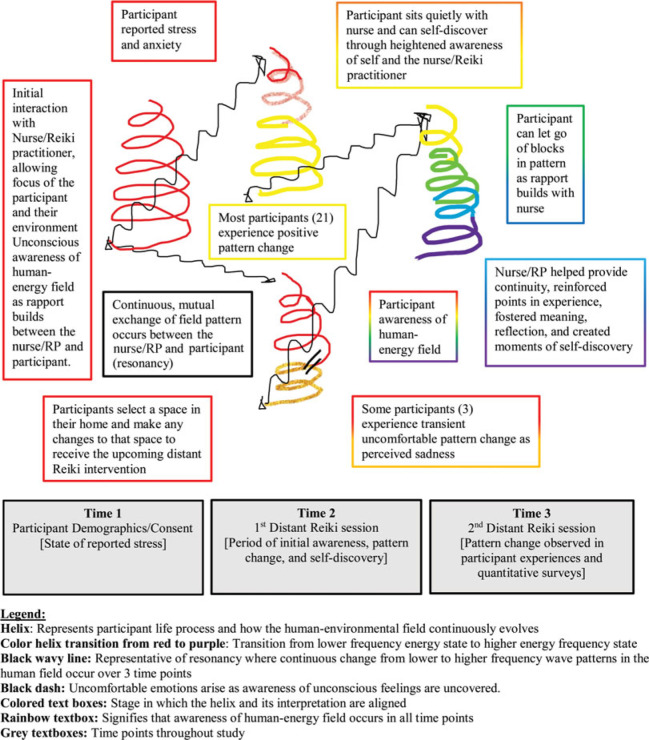

The interpretation of participants' experience with the distant Reiki session is described in Figure 1 along with a corresponding theoretical analysis portrayed in Figure 2. Figure 1 presents an emerging conceptual representation from Rogers' SUHB as reflected in the qualitative data. Each time point outlined the process of participants' experiences with the nurse/RP.

Figure 1.

Participant experiences during distant Reiki intervention.

Figure 2.

Science of Unitary Human Beings and participant responses during distant Reiki intervention.

Time 1 identifies when participants completed their demographics/consent and reported being in a state of perceived stress. Perceived stress and anxiety were most attributed to COVID-19, job, and personal life stressors, and there was some uncertainty of what distant Reiki would entail. Time 1 became a critical time point for participants because it was when the nurse needed to build rapport with participants and help them feel at ease about the distant Reiki experience.

During time 2, participants engaged in the first distant Reiki session and went through a period of initial awareness, pattern change, and self-discovery. What is important to note are the 2 responses that occur at this time, which are both expressed as either positive or transient uncomfortable experiences. The most common response was the positive experience, commonly expressed as feeling relaxed, calm, and peaceful, whereas other participants described experiences of awareness of unconscious, unresolved, and uncomfortable feelings of sadness, which was transient, but impactful to the participant. These participants expressed not being certain about why they felt sad, but after describing their sadness to the researcher felt better and relieved. This sudden realization suggests that when individual become aware of changes in their pattern (eg, blocks) they may experience feelings of sadness or discomfort versus having more positive feelings of openness and self-discovery. All study participants, upon reaching time 3 and receiving the second distant Reiki session, had positive and notable changes in their pattern expression, which are supported in their interview quotes and survey data.

Figure 2 outlines the process that each participant experienced during the study through the lens of Rogerian science. The participant's human field pattern, as represented by the helix (helicy) shape, is a representation of their life process, which never reverts to its original state since the human field is continuous and unidirectional.43 The mutual process, awareness, patterning, and transition between time points demonstrate Rogers' concept of resonancy (black wavy line). During resonancy, the nurse and participant's rapport builds, which helps promote receptivity to the distant Reiki healing. This dynamic further reflects movement in human field patterns from lower frequency wave patterns (as shown in red) to higher frequency wave patterns (as shown in purple) throughout each encounter with the nurse/RP. The participant's pattern manifestation transitions into a state of higher energy frequency, as they receive distant Reiki and move through each time point.

More specifically, participants may or may not have been aware of being engaged in a simultaneous, mutual process and pattern appreciation between the nurse and themselves, which fostered the opportunity for reciprocal and integral presence to be explored between the nurse and the participant. The relationship between the nurse and the participant can enhance pattern change because the nurse, who is also a Reiki Master, consciously focused on and actively listened to the participant. The relationship between the nurse and the participant becomes apparent as their rapport builds, which allows for any noticeable blocks in the participant's pattern to be therapeutically released. The difference that the nurse makes is that it is a holistic encounter, and the nurse-patient relationship is grounded in intentionality with a purpose to assist the patient in self-healing at the bedside. It is through the presence of the other (with distant Reiki as a facilitator) all that nursing becomes visible.44 The manifestation of the evolving nurse-participant rapport is similar to nursing practice and can be realized through the participant's commentary and understanding of their experience. For example, one participant stated: “After the first one, I think I wasn't as relaxed as the second session, just because I didn't know what to expect.” As rapport improved between the nurse and participants, it became less likely for participants to experience perceived manifestations of anxiety during the second session.

Further, the contribution of coming to know the other, grounded in the awareness and visibility of nursing science, is accelerated using a distant Reiki healing modality through participant self-awareness of their true self, their healing environment,10 and by the nurse's recognition of the individual.45 The nurse also brought increased awareness to the environment interaction by encouraging each participant to find a space in their home for the distant Reiki session. Study participants had the opportunity to create new meaning of that space by selecting a specific location in their home and making alterations to that space. Making this choice in the context of the distant Reiki healing sometimes provided insight into the need to change their home environment to promote relaxation.

Another important recognition was that the interrelation between the person and their environment changed during the Reiki session. Some participants noticed that as the session had progressed the music suddenly became too loud, despite no actual change in volume. This experience is likely indicating a change in participants' sensory awareness as they went into a state of deeper relaxation.46 However, no participant asked to lower the sound during the session.

Despite the potential overuse of technology in the socially distant workforce, participants described the ease and benefit of using virtual applications when receiving Reiki. Although this study did not measure virtual burnout, it is important to consider the eyestrain and burnout of using virtual applications as we investigate socially distant healing modalities in future research.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

This study is novel by allowing individuals to receive a distant healing modality that reduces and limits exposure to COVID-19 during a pandemic. Some strengths of this study included recruiting participants both with and without Reiki experience. Having a nurse researcher who is also the RP allowed for adequate education, presence, and openness to build a conducive healing environment and for pattern change to take place. Participants had increased access to receiving distant Reiki from their home, which provided individuals with busy work schedules or driving challenges the opportunity to participate.

There were several limitations to this study. The design was a pilot study with limited statistical power (P < .10) or generalizability. The sham Reiki and control groups were intentionally omitted to be more congruent with Rogerian theory. The individual offering distant Reiki was also the PI of the study, which could lead to bias in participant responses and experiences. Every effort was made to reduce this bias by the PI keeping a reflexivity journal. Participants were asked to verbalize responses of the surveys, which could contribute to participant response bias. More large-scale research is needed to build upon this pilot data.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR NURSING RESEARCH, PRACTICE, AND KNOWLEDGE DEVELOPMENT

Education regarding distant Reiki is strongly encouraged beforehand to reduce pre-distant Reiki session stress and anxiety. Future distant Reiki research should consider including at least 2 distant Reiki sessions for relationship development and rapport building between the nurse and the participant. This action may impact the distant energy healing over time. This is especially important given the occurrence of transient sadness during the first session with some participants. It is also important for researchers to consider whether having Reiki experience determines therapeutic outcomes and in what capacity (distant or in-person). Study participants need to be aware of both positive and potential uncomfortable feelings and consent forms need to describe those Reiki effects. However, uncomfortable feelings are likely transient, as evident in this study. Therefore, it is therapeutically important to consider implementing 2 distant Reiki sessions to reduce the likelihood of leaving one session with uncomfortable emotions as energy receptivity and new pattern changes occur in awareness and self-discovery.

This study informs nursing knowledge development and the need to incorporate energy-based healing modalities into the practice environment, education, and research when investigating complementary therapies on wellbecoming. Nurses frequently have contact with their patients and using Reiki could improve the nurse-patient relationship. Rogers' SUHB provides an important lens for this research to enhance and potentially transform the way nurses practice.

CONCLUSION

Participants were exposed to an innovative nursing distant Reiki study to promote healing and comfort through the lens of Reiki and Rogerian science. Both qualitative and quantitative findings of reduction in perceived manifestations of stress and anxiety showcased positive pattern changes when using a home-based distant healing therapy. Feasibility data showed positive recruitment and retention, which is important given the need for distant healing modalities during the COVID-19 pandemic. There was a noted transformative experience in participant well-being that positions for future, large-scale research by replicating this study using a longer time of data collection and a larger sample size. Distant healing modalities that enhance awareness, reflection, and self-discovery may foster healing that provides meaningful and sustained change. As COVID-19 continues to disrupt our usual pattern of human existence, this study highlights the importance of developing socially distant healing modalities for mental wellness, self-care, and wellbecoming.

Footnotes

The author would like to thank Donna Perry, PhD, RN, for her research mentorship, moral support, and advising throughout the dissertation process. The author would also like to thank Sybil Crawford, PhD, for her assistance with her expertise in statistics. Lastly, the author thanks Dorothy Jones, EdD, APRN, FAAN, FNI, for her theoretical and content expertise.

Jennifer DiBenedetto designed and completed the dissertation with the advisement from her committee members.

This study is a dissertation to fulfill requirements necessary for a PhD in Nursing degree at the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School.

The author has disclosed that she has no significant relationships with, or financial interest in, any commercial companies pertaining to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gloster AT, Lamnisos D, Lubenko J, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health: an international study. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0244809. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0244809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooke JE, Eirich R, Racine N, Madigan S. Prevalence of posttraumatic and general psychological stress during COVID-19: a rapid review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292:113347. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banerjee D. The COVID-19 outbreak: crucial role that psychiatrists can play. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;50:102014. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haleem A, Javaid M, Vaishya R. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic in daily life. Curr Med Res. 2020;10(2):78–79. doi:10.1016/j.cmrp.2020.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Islam S, Ferdous Z, Potenza MN. Panic and generalized anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic among Bangladeshi people: an online pilot survey early in the outbreak. J Affect Disord. 2020;276:30–37. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borges Viana R, Barbosa de Lira CA. Exergames as coping strategies for anxiety disorders during the COVID-19 quarantine period. Games Health J. 2020;9(3):147–150. doi:10.1089/g4h.2020.0060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martínez M, Luis EO, Oliveros EY, et al. Validity and reliability of the Self-Care Activities Screening Scale (SASS-14) during COVID-19 lockdown. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;19(1):1. doi:10.1186/s12955-020-01607-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rand WL. Strengthening your Reiki energy. The International Center for Reiki Training. Accessed September 26, 2021. https://www.reiki.org/reikinews/reikin6.html

- 10.Rogers ME. Nursing science and the space age. Nurs Sci Q. 1991;5(1):27–34. doi:10.1177/089431849200500108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cowling WR. Pattern appreciation: the unitary science practice of reaching essence. In: Madrid M, ed. Patterns of Rogerian knowing. National League for Nursing; 1997:129–142. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thornton LM. A study of Reiki, an energy field treatment, using Rogers' science. Rogerian Nurs Sci News. 1996;8(3):14–15. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner-Cobb JM, Smith PC, Ramchandani P, Begen FM, Padkin A. The acute psychobiological impact of the intensive care experience on relatives. Psychol Health Med. 2016;21(1):20–26. doi:10.1080/13548506.2014.997763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramezani M, Simani L, Karimialavijah E, Rezaei O, Hajiesmaeili M, Pakdaman H. The role of anxiety and cortisol in outcomes of patients with COVID-19. Basic Clin Neurosci. 2020;11(2):179–184. doi:10.32598/bcn.11.covid19.1168.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shevlin M, Nolan E, Owczarek M, et al. COVID-19-related anxiety predicts somatic symptoms in the UK population. Br J Health Psychol. 2020;25(4):875–882. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogers ME. An Introduction to the Theoretical Basis of Nursing. 2nd ed. F. A. Davis; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogers ME. An Introduction to the Theoretical Basis of Nursing. 1st ed. F. A. Davis; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogers ME. Science of unitary human beings. In: Malinski VM, ed. Explorations on Martha Rogers' Science of Unitary Human Beings. Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1986:3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butcher HK, Malinski V, Martha E. Rogers' Science of Unitary Human Beings. In: Smith MC, Parker ME, eds. Nursing Theories and Nursing Practice. 4th ed. F. A. Davis; 2015:242. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baldwin AL, Vitale A, Brownell E, Kryak E, Rand WL. Effects of Reiki on pain, anxiety, and blood pressure in patients undergoing knee replacement: a pilot study. Holist Nurs Pract. 2017;31(2):80–89. doi:10.1097/HNP.0000000000000195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vitale A. An integrative review of Reiki touch therapy research. Holis Nurs Pract. 2007;21(4):167–180. doi:10.1097/01.HNP.0000280927.83506.f6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vitale A, O'Connor PC. The effect of Reiki on pain and anxiety in women with abdominal hysterectomies: a quasi-experimental pilot study. Holis Nurs Pract. 2006;20(6):263–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vitale A. Nurses' lived experience of Reiki for self-care. Holis Nurs Pract. 2009;23(3):129–147. doi:10.1097/01.HNP.0000351369.99166.75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ring ME. Reiki and changes in pattern manifestations. Nurs Sci Q. 2009;22(3):250–258. doi:10.1177/0894318409337014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phillips JR. New Rogerian theoretical thinking about unitary science. Nurs Sci Q. 2017;30(3):223–226. doi:10.1177/0894318417708411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McManus DE. Reiki is better than placebo and has broad potential as a complementary health therapy. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2017;22(4):1051–1057. doi:10.1177/2156587217728644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quek KF, Low WY, Razack AH, Loh CS, Chua CB. Reliability and validity of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) among urological patients: a Malaysian study. Med J Malays. 2004;59(2):258–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Creamer M, Bell R, Failla S. Psychometric properties of the Impact of Events Scale-Revised. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41(12):1489–1496. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiss DS, Marmar CR. The impact of event scale-revised. In: Wilson JP, Keane TM, eds. Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD: A Practitioner's Handbook. Guilford Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCabe D. The Impact of Events Scale-Revised. Try This: Best Practices in Nursing Care to Older Adults. New York University, Rory Meyers College of Nursing; 2019;19. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Julian LJ. Measures of anxiety: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(suppl 11):S467–S472. doi:10.1002/acr.20561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamner L, Dubbel P, Capron I, et al. High SARS-COV-2 attack rate following exposure at a choir practice—Skagit County, Washington, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(19):606–610. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6919e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hart J. Pandemic drives increase in mind-body therapy use: Implications for the future. J Altern Complement Med. 2020;26(6):243–245. doi:10.1089/act.2020.29298.jha [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shore AG. Long-term effects of energy healing on symptoms of psychological depression and self-perceived stress. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004;8(3):42–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Demir M, Can G, Kelam A, Aydiner A. Effects of distant Reiki on pain, anxiety, and fatigue in oncology patients in Turkey: a pilot study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(2):4859–4862. doi:10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.12.4859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.vanderVaart S. A Double-Blinded Randomized Controlled Trial on the Effect of Distant Reiki on Pain After Non-emergency Caesarean Section and the Effect of CYP2D6 Variation of Codeine Analgesia [thesis]. University of Toronto; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dyer NL, Baldwin AL, Rand WL. A large-scale effectiveness trial of Reiki for physical and psychological health. J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25(12):1156–1162. doi:10.1089/acm.2019.0022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Butcher HK. Applications of Rogers' Science of Unitary Human Beings. In: Parker ME, ed. Nursing Theories and Nursing Practice. 2nd ed, F. A. Davis; 2006:167–186. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malinski VM. Explorations on Martha Rogers' Science of Unitary Human Beings. Appelton-Century-Crofts; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barrett EAM, Caroselli C. Methodological ponderings related to the power as knowing participation in change tool. Nurs Sci Q. 1998;11(1):17–22. doi:10.1177/089431849801100106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Butcher HK. Unitariology: research methods: the science of unitary human beings 2.0. In: Martha E. Rogers' Nursing Science. Pressbooks; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Butcher HK. The postulates in the science of unitary human beings: the science of unitary human beings 2.0. In: Martha E. Rogers' Nursing Science. Pressbooks; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aranha PR. Application of Rogers' system model in nursing care of a client with cerebrovascular accident. Manipal J Nurs Health Sci. 2018;4(1):50–56. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hessel JA. Presence in nursing practice: a concept analysis. Holist Nurs Pract. 2009;23(5):276–281. doi:10.1097/HNP.0b013e3181b66cb5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parveen Rasheed S. Self-awareness as a therapeutic tool for nurse/client relationship. Int J Caring Sci. 2015;8(1):211–216. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Staum MJ, Brotons M. The effect of music amplitude on the relaxation response. J Music Ther. 2000;37(1):22–29. doi:10.1093/jmt/37.1.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]