Abstract

Introduction

Recent research underscores the exceptionally young age distribution of COVID-19 deaths in the U.S. compared with that of international peers. This paper characterizes how high levels of COVID-19 mortality at midlife ages (45–64 years) are deeply intertwined with continuing racial inequity in COVID-19 mortality.

Methods

Mortality data from Minnesota in 2020–2022 were analyzed in June 2022. Death certificate data (COVID-19 deaths N=12,771) and published vaccination rates in Minnesota allow vaccination and mortality rates to be observed with greater age and temporal precision than national data.

Results

Black, Hispanic, and Asian adults aged <65 years were all more highly vaccinated than White populations of the same ages during most of Minnesota's substantial and sustained Delta surge and all the subsequent Omicron surges. However, White mortality rates were lower than those of all other groups. These disparities were extreme; at midlife ages (ages 45–64 years), during the Omicron period, more highly vaccinated populations had COVID-19 mortality that was 164% (Asian-American), 115% (Hispanic), or 208% (Black) of White COVID-19 mortality at these ages. In Black, Indigenous, and People of Color populations as a whole, COVID-19 mortality at ages 55–64 years was greater than White mortality at 10 years older.

Conclusions

This discrepancy between vaccination and mortality patterning by race/ethnicity suggests that if the current period is a pandemic of the unvaccinated, it also remains a pandemic of the disadvantaged in ways that can decouple from vaccination rates. This result implies an urgent need to center health equity in the development of COVID-19 policy measures.

INTRODUCTION

The introduction of vaccines for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in early 2021 resulted in a consensus, for a time, that future pandemic surges would lead to a pandemic of the unvaccinated.1 However, limited data are available to evaluate this characterization with respect to racial inequity.2 , 3 This study evaluated whether COVID-19 mortality reflects vaccination rates for different racial/ethnic groups in Minnesota using death certificate data on all COVID-19 deaths from March 2020 to April 2022.

Minnesota was examined because of the unique availability of near‒real-time data on both vaccination status and COVID-19 mortality that are simultaneously separated by race/ethnicity and age. In contrast, national vaccination data that are race/ethnicity specific are not separated by age. Minnesota also stands out for its prolonged and deadly surge of the Delta variant, which did not end until it was supplanted by Omicron at the end of 2021.4 Recent research emphasizes the exceptionally young age distribution of COVID-19 deaths in the U.S. relative to the distribution in other countries.5, 6, 7 Because deaths at midlife ages drove this phenomenon7 and because such deaths exhibited substantial racial/ethnic inequality before vaccines were available,8 this study focuses on vaccination and mortality at these key ages.

METHODS

This analysis uses death certificate data from Minnesota, March 2020‒April 2022; state vaccination data; and National Center for Health Statistics population distributions (Appendix Tables 1 and 2, available online). Mortality patterns were examined in specific racial/ethnic groups at midlife, with a particular focus on fall 2021 and spring 2022, periods of high mortality after widespread vaccination. Sex-specific mortality captures racial disparities independent of differences in sex composition.9 COVID-19 mortality patterns in Minnesota justify the analytic grouping of the state's Black, indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) population, as elaborated in the Appendix (available online).

Deaths were defined as COVID-19 deaths if there was any mention of U07.1 on the death certificate. COVID-19 death and vaccination rates were examined by race/ethnicity and age for 4 pandemic periods corresponding to prevaccination (March 2020–January 2021), mid-vaccination (February 2021–June 2021), Delta-dominated (July 2021–December 2021), and Omicron-dominated (January 2022–April 2022) periods. BIPOC vaccination at elderly ages is likely underestimated in these data, as discussed in the Appendix (available online), which also presents robustness checks (Appendix Figures 1 and 2 , available online).

RESULTS

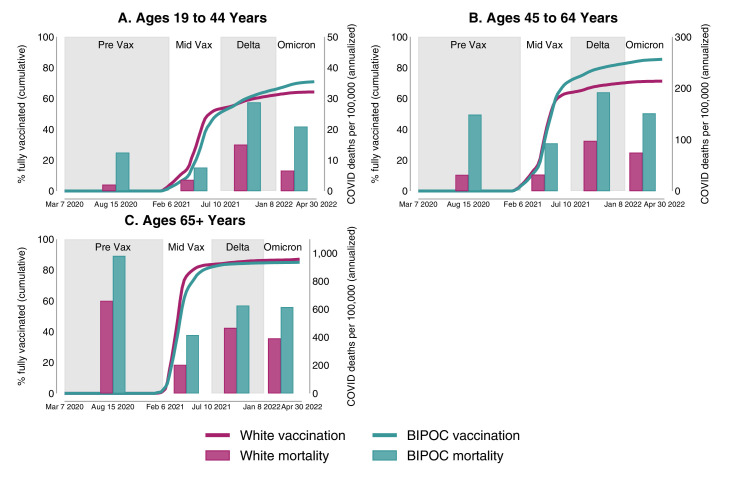

By the end of 2021 in Minnesota, vaccination among White Minnesotans was outpaced by vaccination among BIPOC Minnesotans at midlife ages (45–64 years) as well as young adult ages (19–44 years). Yet, in all age groups and in each phase of the pandemic, White mortality was substantially lower than mortality among Minnesotans of color (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Period-specific Vax rates and COVID-19 mortality rates for White and BIPOC Minnesotans by age.

Note: The lines depict the cumulative Vax progress of each group over time as measured by the percentage of that race-specific, age-specific group that has completed their vaccine series (left axis). The bars depict the race-specific, age-specific mortality rates (right axis) during the pre-Vax period, mid-Vax period, Delta period, and Omicron period of the pandemic. Mortality rates are annualized to facilitate comparison across periods. Vax rates and mortality rates are presented for Minnesotans (A) aged 19–44 years, (B) aged 45–64 years, and (C) aged ≥65 years.

Apr, April; Aug, August; BIPOC, Black, indigenous, and people of color; Feb, February; Jan, January; Jul, July; Mar, March; Vax, vaccination.

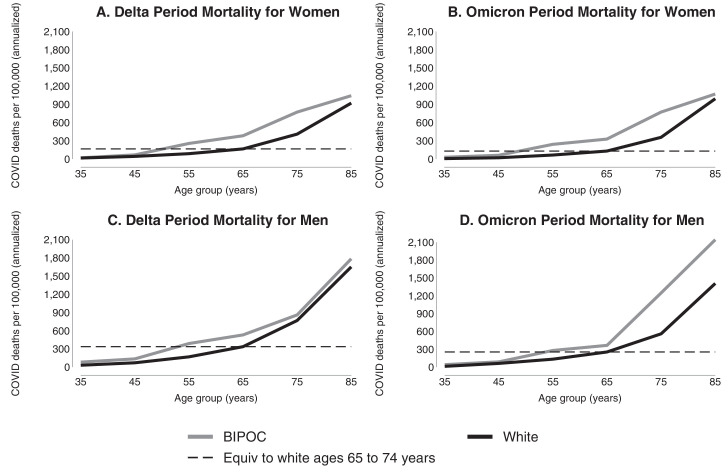

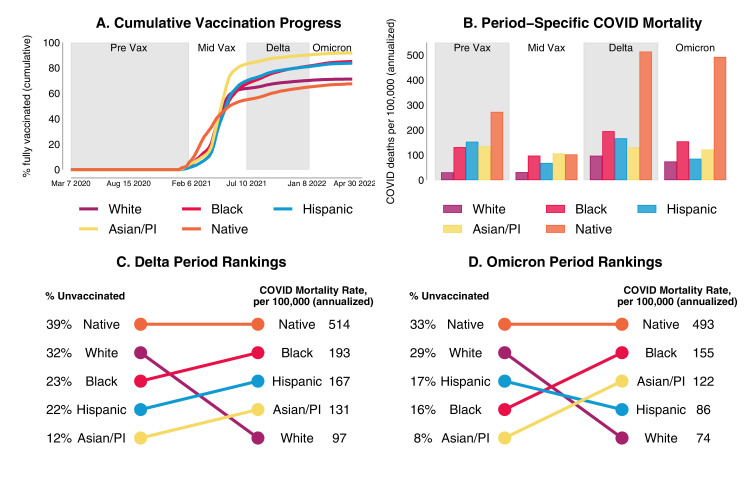

White undervaccination at midlife ages is pronounced: at the end of April 2022, fully vaccinated rates were 85% for BIPOC Minnesotans compared with only 71% for White Minnesotans (Figure 1B). Midlife vaccination for BIPOC Minnesotans is similar to vaccination rates for elderly (aged ≥65 years) White Minnesotans (87%) (Figure 1C). Yet, the gap in BIPOC‒White mortality at those midlife ages was extreme; for example, during the Delta and Omicron periods, BIPOC mortality at ages 55–64 years was higher than White mortality at ages 65–74 years (Figure 2 and Appendix Table 3, available online). At midlife, BIPOC mortality was 4.7 times White mortality in the prevaccination period and about twice as high as White mortality in the Delta and Omicron periods; this pattern also held for Black, Hispanic, and Asian populations individually. At these ages, Minnesota's White population is its second least vaccinated racial/ethnic group, after Native Americans (Figure 3 ). However, despite low vaccination rates, Minnesota's White population aged 45–64 years has lower mortality than that of all other racial/ethnic groups, which ranged from 115% (Hispanic) to 661% (Native) of White mortality during the period dominated by the Omicron variant (Appendix Table 4, available online).

Figure 2.

Period-specific COVID-19 mortality rates by age for White and BIPOC men and women in Minnesota.

Note: The lines depict annualized COVID-19 death rates per 100,000 people (A–B) and during the Delta period early Omicron period, (C–D) through April 2022 by race and sex. The dashed lines in each panel show the relatively lower age at which BIPOC groups experience the same mortality rates as White groups at ages 65–74 years.

BIPOC, Black, Indigenous, and People of Color.

Figure 3.

Period-specific Vax rates and COVID-19 mortality rates at midlife (ages 45–64 years) by race/ethnicity in Minnesota.

(A) The cumulative Vax progress of each racial group over time at midlife as measured by the percentage of that group who have completed their vaccine series. (B) The race-specific mortality rates at midlife during the pre-Vax period, mid-Vax period, Delta period, and Omicron period of the pandemic. (C, D) Comparison of the ranking of racial groups, from worst to best performing, by percent unvaccinated and mortality rates during the (C) Delta period and (D) Omicron period. The Vax data in C–D is from the midpoint of each period (October 2, 2021 for Delta; February 26, 2022 for Omicron) and the mortality rates cover the entire period (July 2021‒December 2021 for Delta; January 2022‒April 2022 for Omicron). All mortality rates are annualized to facilitate comparison across periods.

Apr, April; Aug, August; Feb, February; Jan, January; Jul, July; Mar, March; PI, Pacific Islander; Vax, vaccination.

DISCUSSION

This study found that in Minnesota, despite lower vaccination rates than all but Native Americans from autumn 2021 through April 2022, White people had lower COVID-19 mortality at midlife than Black, Hispanic, Asian, and Native people. The authors note 2 broad possible explanations for these results. One possibility is that racial inequity in COVID-19 mortality risk—owing to differential transmission, comorbidities, or unequal medical access10—among the unvaccinated, the vaccinated, or both may be so great that it overwhelms the differences in vaccination status. A second possibility is that findings may reflect vaccine differences within the fully vaccinated population, with people of color potentially less likely to have received booster vaccinations and less likely to have received mRNA vaccines in their primary series.11

Regardless of the precise mechanism, the findings suggest that the pandemic of the unvaccinated formulation is incomplete and that COVID-19 also remains a pandemic of the disadvantaged. Racial disparities in COVID-19 mortality were smaller during the Delta and Omicron waves than before vaccine availability, suggesting that the vaccination patterns documented in this study may have contributed to lessening these inequities—although declines in RRs across periods should be interpreted cautiously because they partially reflect adverse trends among White populations. Yet, if population mortality primarily reflected population vaccination rates, White communities would have a greater burden of COVID-19 mortality in midlife than communities of color. The fact that the opposite was observed indicates that structural racism, as manifested through systems and policies that affect healthcare access, occupational risk, and housing conditions, continues to fundamentally shape the risk of COVID-19 mortality even in the Delta/Omicron period.12, 13, 14, 15

Although a pandemic of the unvaccinated framing may be used as a rationale for accelerating a return to normal, a pandemic of the disadvantaged framing emphasizes the need for sustained population-based COVID-19 prevention strategies that center on health equity. Such measures could aim to further increase vaccination with community campaigns16 and might also aim to mitigate COVID-19 spread through approaches that protect the vaccinated and unvaccinated alike, including improved ventilation in workplaces and public buildings, paid sick leave, Medicaid expansion and universal health care, economic payments to medically high-risk populations, protective equipment and increased pay for long-term care workers to reduce working multiple jobs, eviction moratoriums and housing support, mask mandates, and public funding for community testing programs and scientific research. These strategies acknowledge that even when vaccine uptake among people of color is relatively high, the mortality of the pandemic remains unequally borne. The pandemic of the disadvantaged framing suggests that a sole emphasis on individual behavior is inadequate for reducing health inequities.

The extent to which findings in Minnesota may resemble those of other states is unclear, particularly because state contexts affect health.17 , 18 If vaccination rates are generally higher in metropolitan areas than in rural areas, other states with very urban populations of color and large rural White populations may show similar vaccination disparities. At the national level, aggregated over age, the White population is vaccinated at lower rates than all but African American individuals,19 and in most states, White vaccination is lower than the high average age of White populations would predict.20 However, the lack of publicly available data on the age composition of vaccine status by race/ethnicity for the U.S. as a whole limits the ability to know how widespread the patterns identified in this study may be.

CONCLUSIONS

Results highlight how distinctive risk at midlife may be intertwined with the deep inequality in U.S. COVID-19 mortality. Populations of color may be at notably high risk—even when they have greater vaccination rates than White people of the same ages.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Minnesota Department of Health and particularly Keeley Morris for sharing data and code that facilitated the analysis and thank Michelle Niemann and Matthew Plummer for their helpful comments.

The interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NIH, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, or the Minnesota Department of Health; no funders played a role in the study design or interpretation of results. Data are available at https://osf.io/bxjkh/?view_only=80e912ce2b624ab7a78e51754c3952e3.

This research was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P2CHD041023, F31HD107980), the National Institute on Aging (P30AG066613, R01AG060115-04S1), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (grant number 77521), and the University of Minnesota School of Public Health.

This study was deemed exempt from full review by the University of Minnesota (STUDY00012527).

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

CRediT AUTHOR STATEMENT

Elizabeth Wrigley-Field: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Software, Writing–original draft. Kaitlyn M. Berry: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing–review and editing. Andrew C. Stokes: Conceptualization, Writing–original draft. Jonathon P. Leider: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing–review and editing.

Footnotes

Supplemental materials associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2022.08.005.

Appendix. SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

REFERENCES

- 1.Sullivan B. U.S. COVID deaths are rising again. Experts call it a “pandemic of the unvaccinated.” NPR. July16, 2021.https://www.npr.org/2021/07/16/1017002907/u-s-covid-deaths-are-rising-again-experts-call-it-a-pandemic-of-the-unvaccinated. Accessed February 18, 2022.

- 2.Ndugga N, Hill L, Artiga S, Haldar S. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2022. Latest data on COVID-19 vaccinations by race/ethnicity.https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/latest-data-on-covid-19-vaccinations-by-race-ethnicity/ Published April 2022. Accessed May 10, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill L, Artiga S. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2022. COVID-19 cases and deaths by race/ethnicity: current data and changes over.https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/covid-19-cases-and-deaths-by-race-ethnicity-current-data-and-changes-over-time/ Published February 2022. Accessed May 10, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Situation update for COVID-19. Minnesota Dept. of Health. https://www.health.state.mn.us/diseases/coronavirus/situation.html. Accessed February 26, 2022.

- 5.Schöley J, Aburto JM, Kashnitsky I, et al. Bounce backs amid continued losses: life expectancy changes since COVID-19 [preprint] bioRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1101/2022.02.23.22271380. Online June 21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demombynes G, de Walque D, Gubbins P, Urdinola BP, Veillard J. The World Bank; Washington, DC: 2021. COVID-19 age-mortality curves for 2020 are flatter in developing countries using both official death counts and excess deaths.https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/718461634217653573/pdf/COVID-19-Age-Mortality-Curves-for-2020-Are-Flatter-in-Developing-Countries-Using-Both-Official-Death-Counts-and-Excess-Deaths.pdf Published October 2021. Accessed May 20, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bor J, Stokes AC, Raifman J, et al. Missing Americans: early death in the United States; 1933–2021 [preprint] medRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1101/2022.06.29.22277065. Online July 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wrigley-Field E, Kiang MV, Riley AR, et al. Geographically targeted COVID-19 vaccination is more equitable and averts more deaths than age-based thresholds alone. Sci Adv. 2021;7(40):eabj2099. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abj2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The sex, gender, and COVID-19 project. The COVID-10 sex-disaggregated data tracker. Global 50 Health 50. https://globalhealth5050.org/covid19/. Accessed July 28, 2022.

- 10.Goldman N, Pebley AR, Lee K, Andrasfay T, Pratt B. Racial and ethnic differentials in COVID-19-related job exposures by occupational standing in the U.S. PLoS One. 2021;16(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faust JS, Renton B, Essien UR, Gounder CR, Lin Z, Krumholz HM. Racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States during the booster roll out [preprint] bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.12.12.21267663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, Bassett MT. How structural racism works–racist policies as a root cause of U.S. racial health inequities. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(8):768–773. doi: 10.1056/NEJMms2025396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McClure ES, Vasudevan P, Bailey Z, Patel S, Robinson WR. Racial capitalism within public health-how occupational settings drive COVID-19 disparities. Am J Epidemiol. 2020;189(11):1244–1253. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwaa126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen YH, Glymour M, Riley A, et al. Excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic among Californians 18-65 years of age, by occupational sector and occupation: March through November 2020. PLoS One. 2021;16(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macias Gil R, Marcelin JR, Zuniga-Blanco B, Marquez C, Mathew T, Piggott DA. COVID-19 pandemic: disparate health impact on the Hispanic/Latinx population in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(10):1592–1595. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bile R, Gilbert A, Mohamed S, Mohammed I, Plummer M, Wrigley-Field E. Lessons from an immigrant-focused community COVID-19 vaccination organization. Health Aff Forefront. https://doi.org/10.1377/forefront.20220518.186581.

- 17.Montez JK, Beckfield J, Cooney JK, et al. U.S. state policies, politics, and life expectancy. Milbank Q. 2020;98(3):668–699. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang X, Warner ME, Grant M. Water shutoff moratoriums lowered COVID-19 infection and death across U.S. states. Am J Prev Med. 2022;62(2):149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Demographic characteristics of people receiving COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States. COVID data tracker. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccination-demographic. Updated XXX. Accessed June 15, 2022.

- 20.Wrigley-Field E, Berry KM, Persad G. Race-specific, U.S. state-specific COVID-19 vaccination rates adjusted for age [preprint] medRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.11.19.21266612. Online November 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.