Abstract

Urinary tract infections are common in infants and children. Pyelonephritis may result in serious complications, such as renal scarring, hypertension, and renal failure. Identification of the timing of release of inflammatory cytokines in relation to pyelonephritis and its treatment is essential for designing interventions that would minimize tissue damage. To this end, we measured urinary cytokine concentrations of interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, and IL-8 in infants and children with pyelonephritis and in healthy children. Children that presented to our institution with presumed urinary tract infection were given the diagnosis of pyelonephritis if they had a positive urine culture, pyuria, and one or more of the following indicators of systemic involvement: fever, elevated peripheral white blood cell count, or elevated C-reactive protein. Urine samples were obtained at the time of presentation prior to the administration of antibiotics, immediately after completion of the first dose of antibiotics, and at follow up 12 to 24 h after presentation. IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 concentrations were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Creatinine concentrations were also determined, and cytokine/creatinine ratios were calculated to standardize samples. Differences between preantibiotic and follow-up cytokine/creatinine ratios were significant for IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 (P < 0.01). Differences between preantibiotic and control cytokine/creatinine ratios were also significant for IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 (P < 0.01). Our study revealed that the urinary tract cytokine response to infection is intense but dissipates shortly after the initiation of antibiotic treatment. This suggests that renal damage due to inflammation begins early in infection, underscoring the need for rapid diagnosis and intervention.

Urinary tract infection (UTI) in infants and children is a relatively common problem, with potentially serious consequences. In an epidemiological study of children up to 11 years of age with symptomatic UTI, Winberg et al. reported an aggregate morbidity risk of 3.0% for girls and 1.1% for boys (37). More recently, Hellström et al. studied 7-year-old Swedish girls and boys and found a history of verifiable UTI in 8.4 and 1.7%, respectively (13). Mårild and Jodal studied children under 6 years of age and found a cumulative incidence of UTI of 6.6% for girls and 1.8% for boys (25). Approximately 30% of these children have vesicoureteral reflux (4, 31). An early study of 596 children with UTI revealed that 4.5% of girls and 13% of boys subsequently develop renal scarring (36). In a study of infants and children with first-time UTI, Pylkkänen et al. (27) found the incidence of renal scars to be 7% when using intravenous urography at 2-year follow-up. However, with the advent of dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) scans, it has been shown that the incidence of renal scarring after acute pyelonephritis is variable, ranging from 10 to 65% (15, 17, 32). Renal scarring has been associated with development of hypertension (12, 16, 31) and end-stage renal disease (1, 9, 12, 16, 24, 30). Of all patients with endstage renal disease, chronic pyelonephritis has been reportedly the cause in 10 to 25% of children (1, 9, 16, 24, 30).

Escherichia coli is the most common organism present (80%) in UTI, although other enteric organisms such as Klebsiella sp. and enterococci, as well as staphylococci, have been identified (21). P fimbriae mediate the attachment of E. coli to intestinal and uroepithelial cells and, along with the lipid A moiety of lipopolysaccharide (endotoxin), have been shown to enhance activation of the host inflammatory response. Cytokines mediate this response (8, 33), including interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-6, and IL-8. In general, IL-1β and IL-6 appear early in the process of inflammation and are involved in lymphocyte proliferation and differentiation, as well as neutrophil activation. IL-8 functions predominantly as a chemotactic factor for neutrophils and is produced locally at the site of infection and resulting inflammation.

In this study, we compare the urinary levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 in patients with pyelonephritis and in healthy children without apparent infection to establish a cytokine profile for pyelonephritis over time and in relation to antibiotic administration. This information will be useful in determining the optimal timing for anti-inflammatory intervention.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient information.

We obtained urine samples from 13 random patients (2 male, 11 female; age, 1 month to 8 years; mean, 29 months) admitted to Children's Hospital of Orange County with the diagnosis of pyelonephritis during the period from February through December 1997. Urine samples were also obtained from nine random healthy children (five male, four female; age, 5 to 18 years; mean, 11 years) who presented to Children's Hospital of Orange County outpatient clinic during the same time period. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was obtained from each child's legal guardian. Cases and controls were not age matched.

Inclusion and/or exclusion criteria.

Patients who presented to our institution with clinical signs and symptoms of UTI were screened. Among patients who had a positive urine culture, the diagnosis of pyelonephritis was established by the presence of pyuria (white blood cell [WBC] counts in in unspun urine of ≥10 cells/high-powered field) and at least one of the following indicators of systemic involvement: temperature of ≥38.5°C, peripheral WBC count of >15,000 cells/μl, or C-reactive protein level of ≥3.0 g/dl. One patient was included who had only 5 to 9 WBCs in unspun urine/hpf because of the presence of a positive urine culture in conjunction with high fever (106°C) and an elevated C-reactive protein level (15.7 g/dl), which is highly suggestive of pyelonephritis.

Patients were excluded if they had history of urinary tract abnormalities, vesicoureteral reflux (VUR), immunosuppression, or antibiotic use (prophylaxis or treatment, except in the case of resistant organisms), a family history of VUR, or a history of previous pyelonephritis.

Urine samples.

Control urine samples were obtained from healthy children who had presented to the clinic for either well-child care or with an unrelated complaint. Urine samples were obtained from patients with pyelonephritis via in-and-out catheterization or clean-catch sampling (if age appropriate) at the time of presentation (preantibiotic), after completion of the first dose of antibiotics (postantibiotic), and 12 to 48 h after presentation (follow-up). Urinalysis was performed by using the Iris Strip method (Iris, Chatsworth, Calif.), and microscopic evaluation was obtained by using the Iris system. Urine cultures were obtained after inoculation of 0.001 ml of urine onto blood agar, as well as inoculation onto the Vitek UID system (bioMérieux). Samples for cytokine analysis were immediately frozen at −70°C.

Cytokine and creatinine assays.

IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 levels were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits commercially available from Immunotech (Westbrook, Maine). The lower limits of detection for IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 were 15, 3, and 8 pg/ml, respectively. Urine creatinine was measured by using a commercially available kit from Sigma Diagnostics (St. Louis, Mo.), and cytokine/creatinine ratios were determined in order to standardize the samples.

Statistics.

The Mann-Whitney rank sum test and Student's t test were used to compare preantibiotic cytokine/creatinine ratios with those of postantibiotic, follow-up, and control samples.

RESULTS

Urine samples were obtained from 13 patients diagnosed with pyelonephritis and from 9 healthy children. However, samples were not available from all patients at all three collection times. No control child was febrile at the time of sample collection. Of children diagnosed with pyelonephritis, all were febrile (38.3 to 41.2°C; mean, 39.6°C) and all had positive urine cultures (E. coli in all cases). The duration of illness prior to presentation ranged from <24 h to 22 days (mean, 4 days), with the majority of patients presenting within 5 days (six patients, ≤1 day; five patients, 1 to 5 days). Initial urinalysis revealed positive nitrite in 6 of 13 samples, a leukocyte esterase level of ≥2+ in 9 of 13 samples, and pyuria in all cases, ranging from 5 to 9 WBCs/hpf (one patient) to TNTC (too numerous to count). Peripheral blood WBC counts ranged from 7,900 to 34,700 cells/μl (mean, 16,100 cells/μl), and the C-reactive protein level was ≥3.0 gm/dl in six of the seven patients tested. Nine patients were treated with broad-spectrum cephalosporins. Of the 10 voiding cystourethrogram studies performed, 3 were reportedly abnormal, demonstrating VUR.

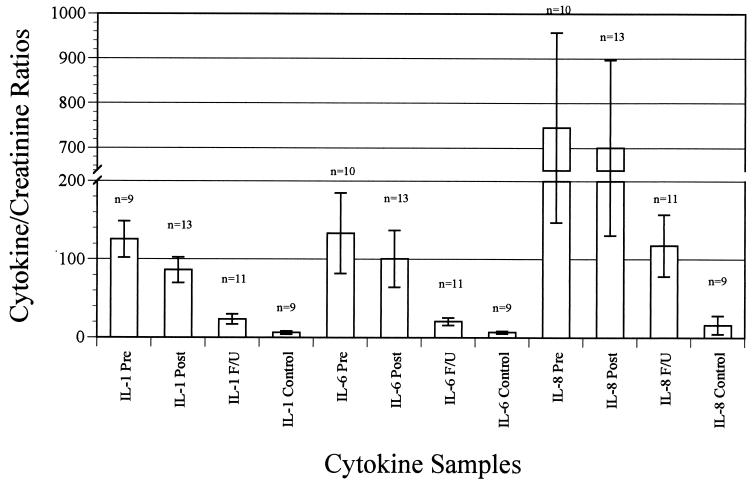

Proinflammatory cytokine concentrations (IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8) and creatinine concentrations were determined in all urine samples. Cytokine/creatinine ratios were calculated to standardize the samples. Table 1 shows the mean cytokine/creatinine ratios for IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 in control subjects and at the three collection points for patients. A graphic representation of these data is presented in Fig. 1.

TABLE 1.

Mean cytokine/creatinine ratios

| Group | Mean ratio ± SEMa (range; n)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1β/Cr | IL-6/Cr | IL-8/Cr | |

| Preantibiotic | 125.17 ± 23.2bc (18.6–2,145; 9) | 133.28 ± 51.5bc (23.9–548.8; 10) | 745.46 ± 212.7bc (140.4–2,195.9; 10) |

| Postantibiotic | 86.32 ± 16.3 (18.7–185.2; 13) | 100.72 ± 36.4 (10.3–468.8; 13) | 700.26 ± 196.2 (99.6–2,625.2; 13) |

| Follow-up | 23.24 ± 6.4d (0–61.6; 11) | 20.53 ± 4.9de (4.0–58.0; 11) | 117.55 ± 39.4de (0–404.1; 11) |

| Control | 6.08 ± 2.2 (0.9–21.4; 9) | 6.62 ± 1.5 (2.1–13.6; 9) | 16.15 ± 11.9 (0–106.9; 9) |

Cr, creatinine; n, number of samples.

Preantibiotic versus follow-up P < 0.01.

Preantibiotic versus control P < 0.01.

Follow-up versus control P < 0.01.

Follow-up versus control P < 0.05.

FIG. 1.

Mean cytokine/creatinine ratios.

High concentrations of cytokines were demonstrated in the initial urine samples, with substantially lower concentrations in the follow-up samples and very low concentrations in the control samples. Of note, one healthy child had detectable concentrations of all three cytokines in the urine sample. Although the child was asymptomatic, the urine Iris Strip results revealed a 2+ leukocyte esterase level without positive nitrite. A review of the medical record revealed no further investigation at the time that the sample was obtained.

The differences between the cytokine/creatinine ratios in the initial urine samples and the follow-up samples were significant for all three cytokines (P < 0.01). The differences between cytokine/creatinine ratios in the initial urine samples and the control samples were also significant for all three cytokines (P < 0.01). The differences between the cytokine/creatinine ratios in the follow-up samples and the control samples were significant for IL-6 (P < 0.01) and IL-8 (P < 0.05) but not for IL-1β.

DISCUSSION

The lipid A component of endotoxin and P fimbriae present in E. coli and other gram-negative bacteria promote an inflammatory reaction that has been linked to renal scarring. Prior studies have shown that IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 participate in this response, and all have been found in elevated quantities in the urine of patients with UTI.

IL-1 is a monokine that works synergistically with other cytokines to promote T-and B-cell proliferation. IL-1 induces cyclooxygenase and lipoxygenase gene expression, induces acute-phase response, induces production of IL-6, and acts as an endogenous pyrogen (19, 22). IL-1β has been detected in urine samples from patients with UTI (3).

IL-6 is a lymphokine which, among other functions, promotes growth and differentiation of T and B cells and acts as an endogenous pyrogen (19, 22). It has been shown that IL-6 levels in urine increase within minutes of mucosal challenge with E. coli expressing P fimbriae and, within hours, polymorphonuclear leukocytes are recruited and excreted into the urine (23). IL-6 has been detected in significantly elevated levels in the urine of patients with UTI (5, 6, 34).

IL-8 is a chemokine that acts as a chemotactic factor for neutrophils, T-lymphocyte subsets, and basophils and activates neutrophils to release lysosomal enzymes, undergo a respiratory burst, and degranulate (19, 22). Production of IL-8 by mesangial cells has been demonstrated in response to IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor alpha but not to lipopolysaccharide (7). Elevated levels of IL-8 have been found in the majority of urine specimens tested from patients with UTI (6, 18, 34). In addition, when specimens were tested for neutrophil chemotactic activity, only urine from infected subjects exhibited activity (18).

Previous studies with animal models have demonstrated that renal scarring is a result of the acute infection rather than the continued presence of microorganisms in the urinary tract (10, 11, 26, 28). Further, early institution of antibiotic therapy has been shown in animal experiments to mitigate the extent of renal scarring (11, 26).

Rushton and colleagues have demonstrated in children with DMSA scintigraphy that the renal parenchyma is capable of recovery from the acute inflammatory changes associated with pyelonephritis (29). These researchers also concluded that acquired renal scarring occurs only at sites corresponding to previous areas of acute pyelonephritis. It follows that early and accurate identification and treatment of patients with acute pyelonephritis would provide the best opportunity for reversal of the inflammatory changes and thus the prevention of renal scarring. In one study of febrile infants less than 1 year of age, 7.5% with no apparent source of infection were found to have UTI (14). This underscores the need to include evaluation for UTI in febrile children, so that appropriate therapy can be initiated in a timely fashion.

Renal scarring has been reported in up to 65% of patients with pyelonephritis. The development of scars in early life, particularly in patients with VUR, has been correlated with the development of hypertension, pre-eclampsia, renal insufficiency, and end-stage renal disease. Tullus et al. showed that the initial IL-6 level in urine of children with pyelonephritis correlated with DMSA uptake defects in the acute phase as well as 1 year later (35). These data suggest that modulating the inflammatory response in patients with UTI should decrease the development of renal scars and the sequelae associated with them. The potential role for immune modulators in sepsis is being intensely evaluated. Previously, meningitis studies showed that the use of steroids blunted the inflammatory response and decreased the frequency of hearing loss (20). The timing of the anti-inflammatory intervention appeared to be crucial in these studies. Arditi et al. demonstrated in an animal model that the use of antibiotics in meningitis resulted in the release of endotoxin, which mediated an increase in inflammatory cytokines (2). These data provide insight into the best time for steroid use in patients with meningitis.

If any intervention is to be instituted to modulate the inflammatory response and decrease the renal scarring that occurs during pyelonephritis, it is critical that we understand the dynamics of cytokine release during this infectious process. To our knowledge, we are the first ones to attempt to establish the point at which peak cytokine release occurs in infection, if antibiotic treatment has any impact on it, and if this process is protracted or short-lived. We had anticipated that we would see an increase in the level of urinary cytokines after the addition of antibiotics, similar to what Arditi et al. observed in meningitis. We had hoped that this would provide a window of opportunity for the potential use of anti-inflammatory intervention. Our results, however, showed that a significant inflammatory process, as evidenced by the levels of IL-6, IL-8, and IL-1β, was already present at the time of diagnosis. Our results also showed that, when appropriate antibiotic treatment is initiated, the inflammatory process ceases rapidly, as noted by cytokine levels returning to control values. Our data strongly suggest, as did those of Hoberman et al. (15), that early recognition and treatment of UTI decrease the occurrence of renal scarring. It is imperative that awareness is raised regarding the frequency of UTI in febrile children, even when infection is not apparent. It also may be inferred from our data that children at risk for recurrent UTI and its sequelae may be candidates to evaluate the safety and efficacy of long-term anti-inflammatory intervention that would blunt cytokine release and minimize the damaging effects of the inflammation that occurs during each recurrence of infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was made possible by financial support from an American Academy of Pediatrics Resident Research Grant and a Children's Hospital of Orange County Pediatric Subspecialty Faculty Research Grant.

REFERENCES

- 1.Advisory Committee to the Renal Transplant Registry. The 11th report of the Human Renal Transplant Registry. JAMA. 1973;226:1197–1204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arditi M, Ables L, Yogev R. Cerebrospinal fluid endotoxin levels in children with H. influenzae meningitis before and after administration of intravenous ceftriaxone. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:1005–1011. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arrieta A C, Sequeira L A, Vargas-Shiraishi O M, Lang D J, Sandborg C. Interleukin (IL)-1α and -β and IL-6 in urine and serum of children urinary tract infection (UTI): diagnostic implications. Pediatr Res. 1995;37(pt. 2):169A. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benador D, Benador N, Slosman D, Mermillod B, Girardin E. Are younger children at highest risk of renal sequelae after pyelonephritis? Lancet. 1997;349:17–19. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)06126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benson M, Jodal U, Andreasson A, Karlsson Å, Rydberg J, Svanborg C. Interleukin 6 response to urinary tract infection in childhood. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:612–616. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199407000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benson M, Jodal U, Agace W, Hellström M, Mårild S, Rosberg S, Sjöström M, Wettergren B, Jönsson S, Svanborg C. Interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8 in children with febrile urinary tract infection and asymptomatic bacteriuria. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:1080–1084. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.5.1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown Z, Strieter R M, Chensue S W, Ceska M, Lindley I, Neild G H, Kunkel S L, Westwick J. Cytokine-activated human mesangial cells generate the neutrophil chemoattractant, interleukin 8. Kidney Int. 1991;40:86–90. doi: 10.1038/ki.1991.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Man P, van Kooten C, Aarden L, Engberg I, Linder H, Svanborg-Eden C. Interleukin-6 induced at mucosal surfaces by gram-negative bacterial infection. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3383–3388. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.11.3383-3388.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gault M H, Dossetor J B. Chronic pyelonephritis: relative incidence in transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 1966;275:813–816. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196610132751504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glauser M P, Lyons J M, Braude A I. Prevention of chronic experimental pyelonephritis by suppression of acute suppuration. J Clin Investig. 1978;61:403–407. doi: 10.1172/JCI108951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glauser M P, Meylan P, Bille J. The inflammatory response and tissue damage: the example of renal scars following acute renal infection. Pediatr Nephrol. 1987;1:615–622. doi: 10.1007/BF00853599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goonasekera C D A, Shah V, Wade A M, Barratt T M, Dillon M J. 15-Year follow-up of renin and blood pressure in reflux nephropathy. Lancet. 1996;347:640–643. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hellström A, Hanson E, Hansson S, Hjälmås K, Jodal U. Association between urinary symptoms at 7 years old and previous urinary tract infection. Arch Dis Child. 1991;66:232–234. doi: 10.1136/adc.66.2.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoberman A, Chao H-P, Keller D M, Hickey R, Davis H W, Ellis D. Prevalence of urinary tract infection in febrile infants. J Pediatr. 1993;123:17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)81531-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoberman A, Wald E R, Hickey R W, Baskin M, Charron M, Majd M, Kearney D H, Reynolds E A, Ruley J, Janosky J E. Oral versus initial intravenous therapy for urinary tract infections in young febrile children. Pediatr. 1999;104:79–86. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobson S H, Eklöf O, Lins L-E, Wikstad I, Winberg J. Long-term prognosis of post-infectious renal scarring in relation to radiological findings in childhood—a 27-year follow-up. Pediatr Nephrol. 1992;6:19–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00856822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jakobsson B, Berg U, Svensson L. Renal scarring after acute pyelonephritis. Arch Dis Child. 1994;70:111–115. doi: 10.1136/adc.70.2.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ko Y-C, Mukaida N, Ishiyama S, Tokue A, Kawai T, Matsushima K, Kasahara T. Elevated interleukin-8 levels in the urine of patients with urinary tract infections. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1307–1314. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1307-1314.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.La Pine T R, Hill H R. Immunomodifiers applicable to the prevention and management of infectious diseases in children. Adv Pediatr Infect Dis. 1994;9:37–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lebel M H, Freij B J, Syrogiannopoulos G A, Chrane D F, Hoyt M J, Stewart S M, Kennard B D, Olsen K D, McCracken G H., Jr Dexamethasone therapy for bacterial meningitis: results of two double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:964–971. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198810133191502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lerner G R. Urinary tract infections in children. Pediatr Ann. 1994;23:463–473. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-19940901-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liles W C, van Voorhis W C. Review: nomenclature and biologic significance of cytokines involved in inflammation and the host immune response. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1573–1580. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.6.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linder H, Engberg I, Hoschützky H, Mattsby-Baltzer I, Svanborg C. Adhesion-dependent activation of mucosal interleukin-6 production. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4357–4362. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4357-4362.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mallick N P, Jones E, Selwood N. The European (European Dialysis and Transplantation Association—European Renal Association) Registry. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;25:176–187. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90642-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mårild S, Jodal U. Incidence rate of first-time symptomatic urinary tract infection in children under 6 years of age. Acta Paediatr. 1998;87:549–552. doi: 10.1080/08035259850158272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller T, Phillips S. Pyelonephritis: the relationship between infection, renal scarring, and antimicrobial therapy. Kidney Int. 1981;19:654–662. doi: 10.1038/ki.1981.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pylkkänen J, Vilska J, Koskimies J. The value of level diagnosis of childhood urinary tract infection in predicting renal injury. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1981;70:879–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1981.tb06244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ransley P G, Risdon R A. Reflux nephropathy: effects of antimicrobial therapy on the evolution of the early pyelonephritis scar. Kidney Int. 1981;20:733–742. doi: 10.1038/ki.1981.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rushton H G, Majd M, Jantausch B, Wiedermann B L, Belman A B. Renal scarring following reflux and nonreflux pyelonephritis in children: evaluation with 99mtechnetium-dimercaptosuccinic acid scintigraphy. J Urol. 1992;147:1327–1332. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37555-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schechter H, Leonard C D, Scribner B H. Chronic pyelonephritis as a cause of renal failure in dialysis candidates. JAMA. 1971;216:514–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smellie J M, Normand I C S, Katz G. Children with urinary tract infection: a comparison of those with and those without vesicoureteral reflux. Kidney Int. 1981;20:717–722. doi: 10.1038/ki.1981.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stokland E, Hellström M, Jacobsson B, Jodal U, Sixt R. Renal damage one year after first urinary tract infection: role of dimercaptosuccinic acid scintigraphy. J Pediatr. 1996;129:815–820. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Svanborg C, Agace W, Hedges S, Linstedt R, Svensson M L. Bacterial adherence and mucosal cytokine production. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1994;730:162–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb44247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tullus K, Fituri L, Burman L G, Wretlind B, Brauner A. Interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 in the urine of children with acute pyelonephritis. Pediatr Nephrol. 1994;8:280–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00866334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tullus K, Fituri O, Linné T, Escobar-Billing R, Wikstad I, Karlsson A, Burman L G, Wretland B, Brauner A. Urine interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 in children with acute pyelonephritis, in relation to DMSA scintigraphy in the acute phase and at 1-year follow-up. Pediatr Radiol. 1994;24:513–515. doi: 10.1007/BF02015016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winberg J, Andersen H J, Bergström T, Jacobsson B, Larson H, Lincoln K. Epidemiology of symptomatic urinary tract infection in childhood. Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl. 1974;252:1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1974.tb05718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Winberg J, Bergström T, Jacobson B. Morbidity, age and sex distribution, recurrences, and renal scarring in symptomatic urinary tract infection in childhood. Kidney Int. 1975;8:S101–S106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]