Abstract

2,3-Di-O-acyl-trehalose (DAT) is a glycolipid located on the outer layer of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell envelope. Due to its noncovalent linkage to the mycobacterial peptidoglycan, DAT could easily interact with host cells located in the focus of infection. The aim of the present work was to study the effects of DAT on the proliferation of murine spleen cells. DAT was purified from reference strains of M. tuberculosis, or M. fortuitum as a surrogate source of the compound, by various chromatography and solvent extraction procedures and then chemically identified. Incubation of mouse spleen cells with DAT inhibited in a dose-dependent manner concanavalin A-stimulated proliferation of the cells. Experiments, including the propidium iodide exclusion test, showed that these effects were not due to death of the cells. Tracking of cell division by labeling with 5,6-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester revealed that DAT reduces the rounds of cell division. Immunofluorescence with an anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody indicated that T lymphocytes were the population affected in our model. Our experiments also suggest that the extent of the suppressive activity is strongly dependent on the structural composition of the acyl moieties in DATs. Finally, the inhibitory effect was also observed on antigen-induced proliferation of mouse spleen cells specific for Toxoplasma gondii. All of these data suggest that DAT could have a role in the T-cell hyporesponsiveness observed in chronic tuberculosis.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the infectious agent of tuberculosis, is responsible for more deaths than any other single pathogen. It causes 2 to 3 million deaths annually and accounts for more than 30% of the deaths of human immunodeficiency virus-positive individuals (13). Factors affecting the pathogenesis of tuberculosis are complex and poorly defined; however, it is well established that the major common feature in chronic tuberculosis is the suppression of the T-cell immune response (3). For instance, while immune depression and immune activation are simultaneously present in tuberculosis, more profound defects in the cell-mediated immunity, which is largely responsible for protection, are clearly correlated with more extensive tissue damages (43).

M. tuberculosis synthesizes both stimulatory and suppressive components for T cells. In general, it is accepted that host-mycobacterium interactions are mediated primarily by specialized molecules expressed on the mycobacterial cell envelope. The immunosuppressive capability of M. tuberculosis is attributed at least in part to lipoarabinomannan (LAM), a major cell wall-associated lipoglycan (21, 28, 29). However, the M. tuberculosis cell wall contains many other distinctive and chemically unusual components, with a predominance of lipid molecules (12). According to data obtained from M. tuberculosis and M. bovis BCG strains, lipid molecules from the cell wall of mycobacteria can migrate outside from the phagocytic vacuole (1, 5). As a consequence, glycolipids noncovalently linked to the peptidoglycan would be able to be incorporated in cell membranes and may alter functions in both phagocytic and nonphagocytic cells located in the focus of infection. More efforts are thus needed in an attempt to identify new extractable immunomodulators from mycobacterial cell walls.

2,3-Di-O-acyl-trehalose (DAT) is a species-specific glycolipid from M. tuberculosis located at the outermost compartment of the cell envelope (33). Its structure, previously believed to include a sulfate group, is that of an amphipathic molecule containing two fatty acyl chains and two moieties of α-glucose (Fig. 1a) (6, 24). DAT is able to induce a humoral immune response, since ca. 80% of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis present antibodies against it (14, 31). Thus, a large distribution of DAT seems to be present in M. tuberculosis virulent isolates, as also supported by lipid analyses of Mexican isolates of the tubercle bacillus (L. M. López Marin, unpublished data). Interesting questions therefore arise about the possible biological importance of DAT in the interaction between mycobacteria and host cells.

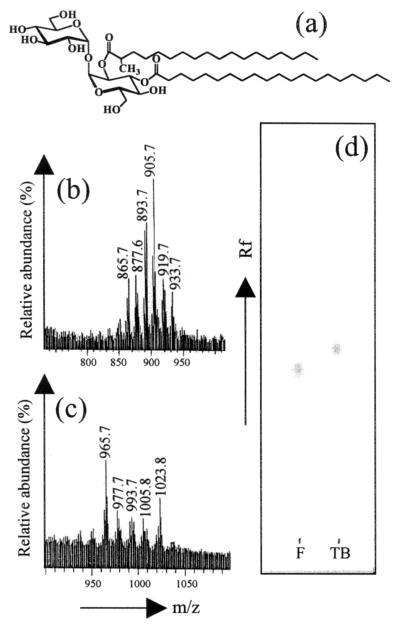

FIG. 1.

Structure and chemical identification of the purified DAT. (a) General chemical structure of DAT. Variations in the carbon chain lengths of the two acyl moieties and presence of insaturations and/or methyl alkylations account for the existence of multiple DAT homologues in each strain. FAB-MS analyses of purified M. fortuitum (b) and M. tuberculosis (c) DATs show the series of pseudomolecular ions [M+Li]+ corresponding to adducts obtained with the different cationized DAT homologues. (d) TLC analysis on silica gel of the purified M. tuberculosis (TB) and M. fortuitum (F) DATs. Solvent, chloroform-methanol-water (60:16:2 [vol/vol/vol]); staining, 0.2% anthrone in sulfuric acid.

In this study we have examined the effects of DAT on the Concanavalin A (ConA)- and antigen-induced proliferation of murine T cells. We studied the proliferation of the cells by monitoring [3H]thymidine incorporation and by using flow cytometry analysis of cells stained with 5,6-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE), a method that allows tracking of individual cell division (27). Since it has been shown that the chemical and antigenic features of DAT purified from M. tuberculosis are very similar to those of DAT from a reference strain of M. fortuitum (2, 6, 18, 24, 44), the latter strain, which is less pathogenic and has a faster growth rate, was used as a surrogate source of the compound for most of the experiments. This is the first time that the effect of DAT on the activation of T lymphocytes is reported.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Glycolipid extraction and purification.

M. tuberculosis H37Rv and M. fortuitum ATCC 6841 were used as sources of DAT. Cultures were grown in Sauton medium at 37°C. Cells were harvested and submitted to lipid extraction as described previously (14). The mycobacterial extracts were concentrated in a rotary evaporator and suspended in chloroform-methanol-water (4:2:1 [vol/vol/vol]); after the separation of the phases, the organic phase was evaporated to dryness and fractionated on Florisil columns (34 by 2.9 cm; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) with chloroform and increasing concentrations of methanol in chloroform (1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 5.0, 7.5, 10.0, 12.5, 15.0, and 20.0%). Analysis of fractions was performed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on silica gel plates (Merck). Glycosylated lipids were monitored by spraying the plates with 0.2% anthrone in sulfuric acid, followed by heating at 110°C for 5 min. DAT-containing fractions were further purified by preparative TLC eluted with chloroform-methanol-water (60:16:2 [vol/vol/vol]) and by precipitation in cold methanol. Finally, DAT was eluted through a prepacked silica gel column (Sep-Pack; Waters, Milford, Mass.) with a gradient of 0 to 20% chloroform-methanol. Solvents were evaporated to dryness, and the residue was weighed. The purified lipid showed a chromatographic mobility consistent with DAT. TLC analyses of the fatty acids released after saponification of DAT (9) excluded the presence of mycolic acyl by-products.

Chemical identification of DAT.

The purified glycolipid was analyzed by TLC on silica gel plates; elution was performed with chloroform-methanol-water (60:16:2 [vol/vol/vol]), and DAT was stained as described above. A mild alkaline deacylation procedure was performed according to the method of Brennan and Goren (7). Briefly, lipids were suspended in chloroform-methanol (2:1 [vol/vol]), and an equivalent volume of 0.2 N NaOH in methanol was added. After incubation for 30 min at 37°C, the reaction mixture was neutralized with acetic acid and allowed to dry. The residue was suspended in chloroform-methanol-water (4:2:1 [vol/vol/vol]), and after 30 s the organic phase was dried, passed through a silica gel column (SepPack; Merck), and eluted with chloroform-methanol (85:15 [vol/vol]). Sugar components of the purified DAT were liberated by hydrolysis with 2 N trifluoroacetic acid for 60 min at 110°C. After extraction with ethylic ether to remove the lipid components, sugars were trimethylsilylated (42) and analyzed on a capillary gas chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector (Varian 3600; Varian Analytical Instruments, Sugar Land, Tex.). A fused silica capillary column (15 m by 0.25 mm, inner diameter) with cross-linked methyl silicone (HP-1; Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, Calif.) was used as the stationary phase. Samples were run using a temperature gradient from 120 to 260°C (4°C/min). Fast-atom bombardment-mass spectrometry (FAB-MS) analyses were generated by using an Autospec-Q tandem hybrid mass spectrometer (Micromass UK, Ltd., Manchester, United Kingdom) as described elsewhere (15). Samples were dissolved in dichloromethane and mixed in the presence of Li+ with meta-nitrobenzyl alcohol as the matrix.

Parasites and preparation of Toxoplasma gondii soluble antigen (TSA2).

TSA2 was obtained from the Wiktor strain of T. gondii as described elsewhere (41). The temperature-sensitive mutant ts-4 strain of T. gondii was maintained in human skin fibroblasts at 33°C as previously described (25).

Immunization of mice with ts-4.

Six-week-old female BALB/c mice were intraperitoneally injected with 2 × 104 tachyzoites of the ts-4 strain in 100 μl of Dulbecco phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) and boosted twice with 2 × 105 tachyzoites by the same route at 3-week intervals.

Cell culture medium.

All reagents were cell culture grade and were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.) or GIBCO (Rockville, Md.). The complete culture medium consisted of RPMI 1640 supplemented with sodium pyruvate (1 mM), nonessential amino acids (0.01 mM), HEPES (25 mM), l-glutamine (2 mM), β-mercaptoethanol (0.05 mM), penicillin (100 U ml−1), streptomycin (100 μg ml−1), and 10% (vol/vol) fetal calf serum (FCS). Polymyxin B (10 μg ml−1) was used instead of penicillin and streptomycin for exploring possible endotoxin contamination of mycobacterial lipid preparations (see Results).

Cell separation.

Spleens were obtained aseptically from normal 6-to 8-week-old BALB/c female mice or from mice infected with the ts-4 strain of T. gondii. Splenocytes were obtained by perfusion, and red blood cells were lysed with hypotonic ammonium chloride solution. For every experiment, cells from at least two mice were pooled and washed twice with DPBS. The number of viable cells was determined by trypan blue exclusion, adjusted to 107 cells/ml in DPBS, and immediately used.

Cell proliferation assay.

DAT was dissolved in hexane-ethanol (1:1 [vol/vol]) at different concentrations, added to each well (100 μl/well) of 96-well, flat-bottom plates (Costar, Cambridge, Mass.), and allowed to dry under sterile conditions. The control wells received solvent alone. Spleen cells (105) were added to the wells and incubated for 2 h at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 in air. Cells were then incubated for 72 h with different concentrations of ConA (Sigma) dissolved in 100 μl of culture medium or for 96 h with different concentrations of TSA2 in the same volume of culture medium. The cells were pulsed with 0.5 μCi of [3H]thymidine (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, England) for the last 18 h and were harvested onto glass fiber filters with an automatic cell harvester (Skatron, Sterling, Va.). The radioactivity uptake was measured by liquid scintillation spectroscopy on a Betaplate counter (Wallac, Turku, Finland). All experiments were performed in triplicate, and results are expressed as the mean counts per minute (cpm) of incorporated [3H]thymidine ± the standard deviation (SD). Results are also expressed as percent proliferation, i.e., [(mean cpm in wells with DAT/mean cpm in wells with solvent alone) × 100].

Staining of cells with CFSE.

CFSE (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) was dissolved to 5 mM in dimethyl sulfoxide and stored in aliquots at −20°C. Cells (5 × 106 cells/ml in DPBS) were stained with 5 μM CFSE in the same buffer (7 min, 37°C in darkness) with occasional stirring. After being stained, cells were washed with complete medium, sedimented by centrifugation (5 min, 469 × g), and suspended in complete medium (106 cells/ml). Stained cells were cultured for 72 h in the presence of DAT and ConA at different doses, under identical conditions to those described for thymidine incorporation experiments.

Cell surface staining.

CFSE-labeled cultured cells (5 × 105) were incubated (30 min, 4°C) with phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (MAb; 0.5 μg in 100 μl of DPBS–1% FCS–0.1% NaN3) from clone 17A2 (Pharmingen, San Diego, Calif.). After three washes with DPBS–1% FCS–0.1% NaN3, the cells were suspended in DPBS and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Determination of viability.

Cell viability was assessed by the exclusion of propidium iodide (PI) according to the method of Ronot et al. (40). Briefly, spleen cells stimulated with ConA for 72 h as described above were harvested, washed once with DPBS, and suspended in 500 μl of the same buffer. Then, 10 μl from a 50-μg/ml solution of PI (Sigma) in DPBS were added to each tube. After incubation for 10 min at room temperature, the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry.

After a 72 h-period of ConA stimulation, CFSE-stained cells were harvested, washed twice with DPBS, and analyzed immediately on a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.) equipped with a 488-nm argon laser. Green fluorescence (CFSE) was detected on the FL1 channel, and red fluorescence (PI and PE) was detected on the FL2 channel. A total of 20,000 events of each sample were captured and analyzed by using the CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson). Lymphocytes and blasts were identified by forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) characteristics.

RESULTS

Purification and chemical characterization of DAT.

Although DAT is not shared by mycobacteria closely related to the tubercle bacillus, i.e., M. bovis and M. bovis BCG (34), a few strains of M. fortuitum have proved to synthesize this antigenic molecule (2, 18). Moreover, DAT purified from both M. tuberculosis and M. fortuitum reference strains have been shown to be interchangeable in terms of antigenicity (44). We therefore decided to use M. fortuitum ATCC 6841, a rapid grower, as a surrogate source to obtain DAT. Purification of DAT was performed by adsorption chromatography from phosphorus-free lipid fractions. The fractions were monitored by TLC, and those containing the glycolipid were pooled and passed through a silica gel column (SepPack). Further purification was achieved by precipitation in cold methanol, a step to eliminate contaminating mono-mycoloyl-trehalose, another extractable mycobacterial glycolipid. A similar procedure was used to purify DAT from M. tuberculosis.

When analyzed by TLC, both M. fortuitum and M. tuberculosis DATs showed positive anthrone-sulfuric acid staining. Similarly, both compounds were found to be labile to a mild alkali treatment and presented a migration pattern characteristic of standard DAT preparations. Gas chromatography of the trimethylsylyl derivatives of the released sugars after acid hydrolysis of DATs established that glucose and residual trehalose were the carbohydrate components (data not shown). When the samples were analyzed by FAB-MS in the positive-ion mode, a family of adducts corresponding to [M+Li]+ pseudomolecules could be observed (Fig. 1b and c). For M. fortuitum DAT, the mass spectrum showed a strong ion current at m/z 905.7 [M+Li]+, flanked by peaks differing by ± 12, 14, 28, 30, and 32 atomic mass units (Fig. 1b). The spectrum of DAT from M. tuberculosis presented two strong signals at m/z 965 and 1,023 [M+Li]+, accompanied by lesser peaks at m/z 977, 993, and 1005 (Fig. 1c). These data confirmed the presence of families of various DAT homologues differing by the number of methylene units and/or by the presence of insaturations in the fatty acyl portions of DATs, as has been previously reported (2, 6, 18). Additionally, the spectra indicated the presence of homologues containing longer fatty acyl chains in DAT purified from M. tuberculosis. This was an expected feature since longer species-specific fatty acids characterize the tubercle bacillus (6). As a consequence, a slight difference on the TLC migration profiles could be observed between the two purified DATs (Fig. 1d).

In conclusion, with a carbohydrate composition, a chromatography mobility, and molecular masses consistent with DATs, the identity of the purified molecules could be assessed.

Effects of M. fortuitum DAT on ConA-induced T-cell proliferation.

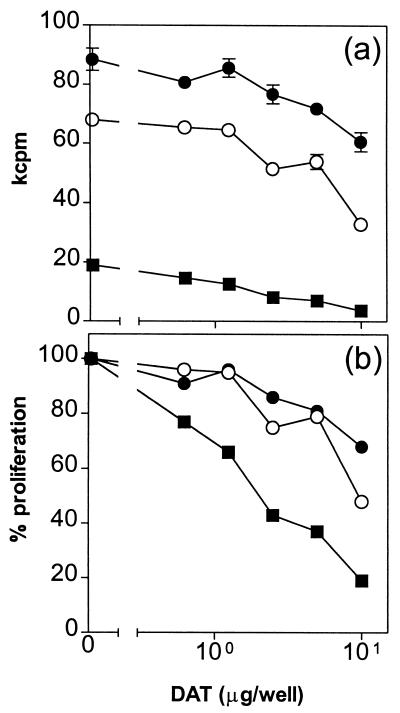

We first tested the effect of DAT isolated from M. fortuitum in the proliferation of mouse spleen cells by stimulating them with the mitogen ConA. After treatment of the cells with different concentrations of the lipid, a dose-dependent inhibition in the [3H]thymidine incorporation was observed (Fig. 2a); the inhibitory effect of the compound was found with concentrations of ConA ranging from 0.3 to 3.0 μg/ml. When the results were expressed as a percentage of proliferation (Fig. 2b), inhibitions up to 48 and 82% were observed when ConA was used at 1.0 and 0.3 μg/ml, respectively, in the presence of 10 μg of DAT (Fig. 2b).

FIG. 2.

DAT inhibits ConA-induced proliferation of mouse spleen cells. Spleen cells were stimulated with 0.3 (■), 1.0 (○), and 3.0 μg (●) of ConA/ml in the presence of different DAT concentrations from M. fortuitum, and the proliferation was assessed by monitoring [3H]thymidine incorporation as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as mean kilocounts per minute of triplicate cultures ± the standard deviations (a) and as the percent proliferation, i.e., [(mean cpm from wells with DAT/mean cpm from wells with solvent alone) × 100] (b).

In order to eliminate the possibility that the inhibition observed was induced by endotoxin contamination of the samples, we performed the same proliferation assays but in the presence of polymyxin B, an inhibitor of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) activity. No abrogation of the suppressive activities of DAT on [3H]thymidine incorporation could be detected (data not shown), thus indicating that the inhibition observed was caused by DAT and not by eventual LPS contamination of the sample.

To rule out the possibility that the suppressive effect of DAT on T cells was due to a toxicity of the compound, we analyzed the viability of the cells both treated and not treated with DAT by performing a PI exclusion test at the end of the 72 h-incubation period. As seen in Table 1, the mean mortality of stimulated cells did not exceed 7.0% when treated with 0.625 to 5.0 μg of DAT per well, while cells treated with 10.0 μg of DAT per well showed 17% mortality.

TABLE 1.

Effect of DAT from M. fortuitum on cell viability with splenocytes activated by ConA

| DAT concn (μg/well) | Cell viabilitya in expt:

|

Avg | SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| 0.625 | 0.975 | 1.050 | 0.932 | 0.985 | 0.048 |

| 1.250 | 0.996 | 1.080 | 0.867 | 0.981 | 0.087 |

| 2.500 | 0.958 | 1.040 | 0.900 | 0.966 | 0.057 |

| 5.000 | 0.941 | 1.050 | 0.820 | 0.937 | 0.093 |

| 10.000 | 0.775 | 0.960 | 0.760 | 0.831 | 0.080 |

Viability is expressed as the ratio between the percentage of PI-negative cells in the presence of DAT and PI-negative cells in the control wells. These data represent the results of three experiments conducted with different cell pools.

DAT induces a decrease in the rounds of T cell division.

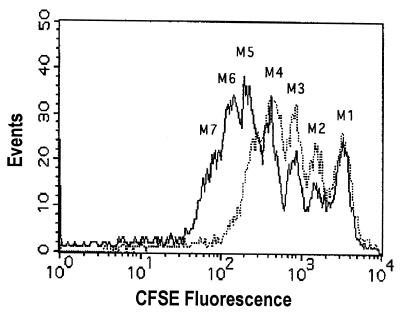

In order to obtain more information about the effect of DAT on the proliferative capability of the cells, splenocytes were labeled with the fluorescein-based dye CFSE, and the cell proliferation was tracked by use of flow cytometry. As reported earlier, this method is based on the sequential halving of the cell fluorescence after each division, which allows study of the division history of individual cells (27). As seen in Fig. 3, cells stimulated with ConA for 3 days showed six rounds of division (populations marked as M2-M7); in contrast, cells stimulated in the presence of DAT from M. fortuitum (10 μg/well) only presented four rounds of division (populations M2-M5). Therefore, the presence of M. fortuitum DAT caused a deficit of two rounds of cell division. These observations confirmed that cells stimulated with ConA in the presence of DAT proliferated less than did control cells.

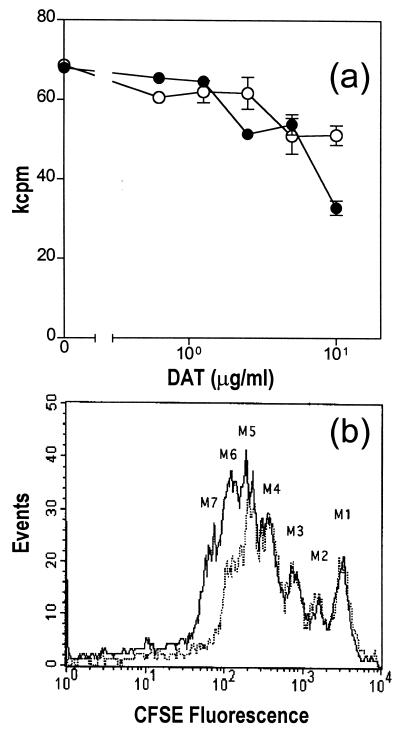

FIG. 3.

DAT reduces the rounds of cell divisions. Spleen cells stained with CFSE were added into control wells (solid line) or wells containing 10 μg of DAT (dotted line), stimulated with ConA for 72 h, and analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) as described in Materials and Methods. The lymphocyte region was first identified by FSC and SSC characteristics, gated, and analyzed for CFSE fluorescence.

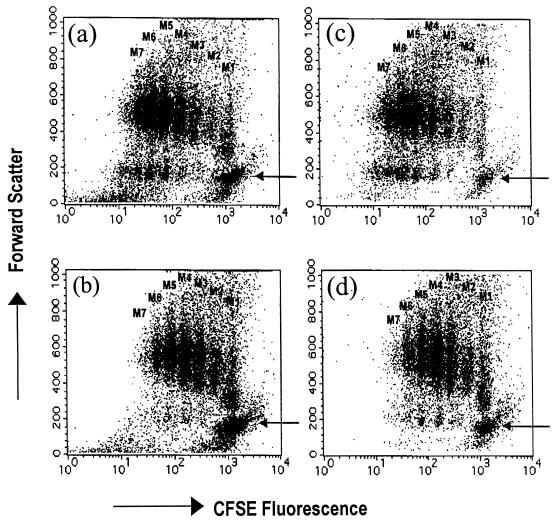

Dot plots with a bivariant analysis by cell size (FSC) and CFSE fluorescence were also obtained. As shown in Fig. 4a and 4b, a higher population of small, nonproliferating cells in the presence of DAT was observed compared to the control (arrow).

FIG. 4.

DAT delays blastic transformation of ConA-stimulated T cells. Mouse spleen cells stained with CFSE were treated as described in Fig. 3 and analyzed by their size (FSC) and by the CFSE fluorescence. (a) Cells in control wells. (b) Cells in wells treated with 10 μg of DAT from M. fortuitum. The same cells were further stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD3 MAb and analyzed also by CFSE fluorescence of cells in control wells (c) and cells in wells treated with 10 μg of DAT (d). Panels a and b are the bivariate dot plots of the total population of cells acquired (20,000 events), and panels c and d are the dot plots of the CD3+ gated cells. The arrows indicate the population of resting cells.

To confirm that T lymphocytes were the population affected by DAT, cells were costained with an anti-CD3 MAb at the end of the experiments. When CD3+ cells were first gated and then analyzed in the bivariate dot plot of FSC versus CFSE fluorescence, we observed that seven rounds of divisions of the CD3+ cells were achieved in the absence of DAT and that only a minimal number of resting T cells, identified by their small size (arrow), were present (Fig. 4c). In contrast, the addition of DAT induced a higher number of resting T cells (Fig. 4d). These experiments suggest that DAT delays the ConA-induced blastic transformation and proliferation of mouse T lymphocytes.

Effects on the proliferative response by M. tuberculosis DAT.

The experiments described thus far were performed with the DAT isolated from M. fortuitum, an antigenically equivalent analogue of DAT isolated from the tubercle bacillus (44). We therefore tested whether DAT purified from M. tuberculosis induced the same effect. As shown in Fig. 5a, DAT isolated from M. tuberculosis also induced an inhibition of the ConA-induced proliferation of mouse spleen cells as reflected by [3H]thymidine incorporation. However, the strength of the inhibition was surprisingly lower than that observed with DAT from M. fortuitum (see Fig. 2 and 5a). When the cell divisions were analyzed by flow cytometry in CFSE-stained cells, only one peak of cell division was lacking in the presence of 10 μg of DAT per well, compared to the control (Fig. 5b). These results showed that M. tuberculosis DAT also inhibits the proliferation of mouse T cells, but the effect is lower than that observed with DAT isolated from M. fortuitum.

FIG. 5.

Effect of DAT isolated from M. tuberculosis on the proliferation of mouse spleen cells stimulated with ConA. (a) Spleen cells were stimulated with ConA in the presence of different concentrations of DAT from M. fortuitum (●) or M. tuberculosis (○), and proliferation was assessed by monitoring [3H]thymidine incorporation as described in Material and Methods. (b) Parallel experiments were performed with CFSE-stained spleen cells and analyzed by FACS as described in Fig. 3. Solid line, cells in control wells; dotted line, cells in wells containing 10 μg of DAT from M. tuberculosis.

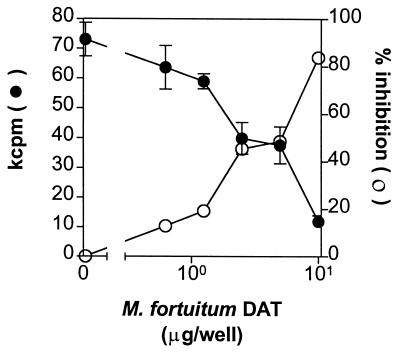

Addition of DAT inhibits antigen-induced proliferative response.

We tested whether the inhibitory effect of DAT on the proliferation of T cells described above was also observed when T lymphocytes were activated by its antigen, which is the innate stimulus for T cells. We stimulated spleen cells from T. gondii-infected mice with total soluble lysate of the parasite (TSA2) in the presence of different concentrations of DAT purified from M. fortuitum. As shown in Fig. 6, a dose-dependent hyporesponsiveness to TSA2 (1 μg/ml) was observed with the addition of DAT; the same inhibitory effect of DAT was observed with TSA2 concentrations ranging from 0.3 to 3.0 μg/ml (data not shown). DAT from M. tuberculosis also induced a dose-dependent inhibition of the antigen-induced proliferation (data not shown). Thus, the inhibitory effect of DAT is also observed when T cells are activated with an antigen.

FIG. 6.

DAT decreases the proliferation of T. gondii-specific cells. Spleen cells from mice infected with T. gondii were stimulated with parasite soluble antigen (TSA2) in the presence of different DAT concentrations from M. fortuitum, and the proliferation was assessed by monitoring [3H]thymidine incorporation. The results are expressed in kcpm, and the percent inhibition (100 − percent proliferation).

DISCUSSION

We report here that DAT, a mycobacterial cell wall glycolipid, inhibits the proliferation of mouse T cells in a dose-dependent manner. The inhibition of proliferation was not caused by a toxic effect of the compound, since cell viability at the end of the experiment was minimally affected by the presence of DAT.

The use of the fluorescein-based dye CFSE for cell staining (27) allowed us to obtain detailed information on the division of individual cells, specifically to record the number of rounds of cell division. Additionally, in combination with flow cytometry, information concerning the phenotype of the proliferating cells could be obtained. Using this technique, we observed that cells incubated with DAT and stimulated with ConA showed one to two rounds of cell division fewer than did the control cells, suggesting that DAT delays the proliferation of T lymphocytes. Moreover, forward-size characteristics indicated an inhibition of the blastic transformation by DAT, and immunofluorescence experiments with an anti-CD3 MAb showed that T cells were indeed the population of cells affected by the glycolipid.

Most of the experiments described here were performed with M. fortuitum as a surrogate source of DAT. When we used DAT derived from M. tuberculosis, the same inhibitory effect on the proliferation of T cells was also observed, but to a lesser degree. When we take into account that different fatty acyl compositions are present in the two isolated molecules, a mean molecular mass can be calculated for each DAT family. In light of the relative percentages of the different glycolipid pseudomolecules observed by MS (Fig. 1b and c), molecular masses of 892 and 980 Da were obtained for M. fortuitum and M. tuberculosis DATs, respectively. Thus, despite the fact that the molar doses of glycolipid differed by ca. 10% between the two tested compounds, a less-pronounced activity with M. tuberculosis DAT is still inferred. This quantitative difference in the inhibitory effect observed between the two compounds could be due to fine structural variations in their acyl moieties. Ladisch et al. have shown that fatty acyl variations are crucial for the extent of the immunosuppressive activity of gangliosides (22). These authors found that the shorter the fatty acyl chain in these glycosphingolipids, the stronger their immunomodulatory effect. In contrast, lipid structural variations seem not to be involved in antigenic recognition of DAT (44), as is the case for some glycosphingolipids (10, 32).

A very interesting point in the present work is that DAT not only inhibited mitogen-induced proliferation of T cells but also antigen-driven blastogenesis. The inhibition of mitogen and antigen-driven proliferation of T cells has also been reported for LAM and phenolic glycolipid, two other mycobacterial immunomodulators (17, 29, 38). We decided to test the effect of DAT on the proliferation of spleen cells obtained from mice infected with the ts-4 strain of the pathogenic parasite T. gondii. Mice infected with the ts-4 strain of this parasite develop a strong cellular immune response that protects against challenge with virulent T. gondii (46, 47).

Protective immunity against M. tuberculosis is cell mediated. A major feature of the chronic phase of tuberculosis is a T-cell dysfunction, which can been shown in terms of anergy, proliferative block, and altered cytokine secretion (3). Both antigen-specific and more generalized T-cell dysfunctions have been characterized during tuberculosis (21, 45). The effects herein reported for DAT are thus likely to play a role in the immunosuppressive mechanisms produced by M. tuberculosis. An indirect evidence that support this hypothesis is the fact that DAT inhibited the proliferation of T cells specific for T. gondii.

In fact, a role for DAT in T-cell dysfunctions is not out of the question; several reports have shown that mycobacterial lipids escape from Mycobacterium-containing phagosomes to other vacuoles in the same phagosome, outside of the phagocytic cell, and to noninfected closely located cells (1, 5). In addition, some studies have described the persistence of mycobacterial glycolipids within host cells (20, 39), a phenomenon probably related to the lack of lysosomal enzymes able to efficiently digest these structurally peculiar glycoconjugates during the long-lasting growth of the bacilli.

Other bacterial glycolipids have been shown to suppress T-cell functions affecting either T-cell subsets (17) or antigen-presenting cells through mechanisms that include interference with antigen presentation (16) or the release of inhibitory factors such as PGE-2 (4). In addition, some authors have suggested that the immunomodulatory effects caused by glycolipids are nonspecific and may be correlated with the impairment of membrane-linked functions caused by the insertion of these compounds in host cells (4, 17, 23). In support of this hypothesis, a great variety of glycolipids from different sources have been found to inhibit lymphoproliferative responses, regardless their different antigenic properties (4, 17, 19, 35–38). Moreover, two lipids, namely, a multiglycosylated glycopeptidolipid and its alkali β-eliminated product, have been found to cause membrane perturbations in a way that seems to be correlated to the extent of their immunomodulatory properties (26, 36). Membrane alterations have recently been shown to be crucial for the so-called immunological synapse, which leads to T-cell activation (8). According to data obtained with DAT concerning their antigenic and immunomodulatory properties (reference 44 and the present study), we can hypothesize that membrane perturbations, and not antigenically specific recognitions, may be involved in the T-cell effects herein reported for DAT.

Finally, it is noteworthy that there is evidence indicating that DAT is also synthesized by M. leprae (11, 34, 39). Furthermore, anti-DAT antibodies have been found not only in individuals affected by tuberculosis but also in most lepromatous leprosy patients (11). Thus, the chemical basis of this cross-reactivity between DAT and M. leprae cells is of great interest. For instance, the presence of DAT in M. leprae cells could also account for some immunosuppressive effects reported in LAM- and phenolic glycolipid-free lipid extracts obtained from this species (30).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant 33578M from CONACYT (Mexico).

We thank P. Hérion for critical reading of the manuscript and T. D. Williams (Kansas University) for the FAB-MS analyses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aldwell F E, Dicker B L, Da Silva Tatley F M, Cross M F, Liggett S, Mackintosh C G, Griffin F T. Mycobacterium bovis-infected cervine alveolar macrophages secrete lymphoreactive lipid antigens. Infect Immun. 2000;68:7003–7009. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.12.7003-7009.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ariza M A, Valero-Guillen P L. Delineation of molecular species of a family of diacyltrehaloses from Mycobacterium fortuitum by mass spectrometry. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;119:279–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes P F, Modlin R L, Ellner J J. T-cell responses and cytokines. In: Bloom B R, editor. Tuberculosis: pathogenesis, protection, and control. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. pp. 417–435. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrow W W, Davis T L, Wright E L, Labrousse V, Bachelet M, Rastogi N. Immunomodulatory spectrum of lipids associated with Mycobacterium avium serovar 8. Infect Immun. 1995;63:126–133. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.1.126-133.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beatty W L, Rhoades E R, Ullrich H J, Chatterjee D, Heuser J E, Russell D G. Trafficking and release of mycobacterial lipids from infected macrophages. Traffic. 2000;1:235–247. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Besra G S, Bolton R C, McNeil M R, Ridell M, Simpson K E, Glushka J, van Halbeek H, Brennan P J, Minnikin D E. Structural elucidation of a novel family of acyltrehaloses from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochemistry. 1992;31:9832–9837. doi: 10.1021/bi00155a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brennan P J, Goren M B. Structural studies on the type-specific antigens and lipids of the Mycobacterium avium-Mycobacterium intracellulare-Mycobacterium scrofulaceum serocomplex. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:4205–4211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown M J, Shaw S. T-cell activation: interplay at the interface. Curr Biol. 1999;9:R26–R28. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buitrón G, González A, López-Marín L M. Biodegradation of phenolic compounds by an acclimated activated sludge and isolated bacteria. Water Sci Technol. 1998;37:371–378. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crook S J, Boggs J M, Vistnes A, Koshy K M. Factors affecting surface expression of glycolipids: influence of lipid environment and ceramide composition on antibody recognition of cerebroside sulfate in liposomes. Biochemistry. 1986;25:7488–7494. doi: 10.1021/bi00371a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cruaud P, Yamashita J T, Martin Casabona N, Papa F, David H L. Evaluation of a novel 2,3-diacyl-trehalose-2′-sulphate (SL-IV) antigen for case finding and diagnosis of leprosy and tuberculosis. Res Microbiol. 1990;141:679–694. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(90)90062-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daffé M, Draper P. The envelope layers of mycobacteria with reference to their pathogenicity. Adv Microb Physiol. 1998;39:131–203. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enarson D A, Murray J F. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis. In: Rom W N, Garay S, editors. Tuberculosis. New York, N.Y: Little, Brown & Co.; 1996. pp. 57–75. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Escamilla L, Mancilla R, Glender W, López-Marín L M. Mycobacterium fortuitum glycolipids for the serodiagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 1996;154:1864–1867. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.6.8970382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esch S W, Morton M D, Williams T D, Buller C S. A novel trisaccharide glycolipid biosurfactant containing trehalose bears ester-linked hexanoate, succinate, and acyloxyacyl moieties: NMR and MS characterization of the underivatized structure. Carbohydr Res. 1999;319:112–123. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(99)00122-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forestier C, Deleull F, Lapaque N, Moreno E, Gorvel J P. Brucella abortus lipopolysaccharide in murine peritoneal macrophages acts as a down-regulator of T cell activation. J Immunol. 2000;165:5202–5210. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fournie J F, Adams E, Mullins R J, Basten A. Inhibition of human lymphoproliferative responses by mycobacterial phenolic glycolipids. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3653–3659. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.11.3653-3659.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gautier N, López-Marin L M, Lanéelle M A, Daffé M. Structure of mycoside F, a family of trehalose-containing glycolipids of Mycobacterium fortuitum. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;78:171–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90136-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giorgio S, Jasiulionis M G, Straus A H, Takahashi H K, Barbieri C L. Inhibition of mouse lymphocyte proliferative response by glycosphingolipids from Leishmania (L.) amazonensis. Exp Parasitol. 1992;75:119–125. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(92)90127-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hooper L C, Johnson M M, Khera V R, Barrow W W. Macrophage uptake and retention of radiolabeled glycopeptidolipid antigens associated with the superficial L1 layer of Mycobacterium intracellulare serovar 20. Infect Immun. 1986;54:133–141. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.1.133-141.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaplan G, Gandhi R R, Weinstein D E, Levis W R, Patarroyo M E, Brennan P J, Cohn Z A. Mycobacterium leprae antigen-induced suppression of T cell proliferation in vitro. J Immunol. 1987;138:3028–3034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ladisch S, Li R, Olson E. Ceramide structure predicts tumor ganglioside immunosuppressive activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1974–1978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lanéelle G, Daffé M. Mycobacterial cell wall and pathogenicity: a lipidologist's view. Res Microbiol. 1991;142:433–437. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(91)90116-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lemassu A, Lanéelle M A, Daffé M. Revised structure of a trehalose-containing glycolipid of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;78:171–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(91)90153-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leyva R, Hérion P, Saavedra R. Genetic immunization with plasmid DNA coding for the ROP2 protein of Toxoplasma gondii. Parasitol Res. 2001;87:70–79. doi: 10.1007/s004360000296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.López-Marín L M, Quesada D, Lakhdar-Ghazal F, Tocanne J F, Lanéelle G. Interactions of mycobacterial glycopeptidolipids with membranes: influence of carbohydrate on induced alterations. Biochemistry. 1994;33:7056–7061. doi: 10.1021/bi00189a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lyons A B, Parish C R. Determination of lymphocyte division by flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 1994;171:131–137. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Molloy A, Gaudernack G, Levis W R, Cohn Z A, Kaplan G. Suppression of T-cell proliferation by Mycobacterium leprae and its products: the role of lipopolysaccharide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:973–977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.3.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moreno C, Mehlert A, Lamb J. The inhibitory effects of mycobacterial lipoarabinomannan and polysaccharides upon polyclonal and monoclonal human T cell proliferation. Clin Exp Immunol. 1988;74:206–210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moura A C N, Mariano N. Lipids from Mycobacterium leprae cell wall suppress T-cell activation in vivo and in vitro. Immunology. 1997;92:429–436. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00366.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muñoz M, Lanéelle M-A, Luquin M, Torrelles J, Julián E, Auxina V, Daffé M. Occurrence of an antigenic triacyl trehalose in clinical isolates and reference strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;157:251–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakakuma H, Arai M, Kawaguchi T, Horikawa K, Hidaka M, Sakamoto K, Iwamori M, Nagai Y, Takatsuki K. Monoclonal antibody to galactosylceramide: discrimination of structural difference in the ceramide moiety. FEBS Lett. 1989;258:230–232. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81660-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ortalo-Magné A, Lemassu A, Lanéelle M A, Bardou F, Silve G, Gounon P, Marchal G, Daffé M. Identification of the surface-exposed lipids on the cell envelopes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other mycobacterial species. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:456–61. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.2.456-461.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Papa F, Cruaud P, David H L. Antigenicity and specificity of selected glycolipid fractions from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Res Microbiol. 1989;140:569–578. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(89)90089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Persat F, Vincent C, Schmitt D, Mojon M. Inhibition of human peripheral blood mononuclear cell proliferative response by glycosphingolipids from metacestodes of Echinococcus multilocularis. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3682–3687. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3682-3687.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pourshafie M, Ayub Q, Barrow W W. Comparative effects of Mycobacterium avium glycopeptidolipid and lipopeptide fragment on the function and ultrastructure of mononuclear cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;93:72–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb06499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pourshafie M R, Davis S A, Sonnenfeld G. Cellular interactions of murine immune cells exposed to live Mycobacterium intracellulare, its whole lipid extract, and its serovar-specific glycopeptidolipid. Cell Immunol. 1994;155:11–26. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1994.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prasad H K, Mishra R S, Nath I. Phenolic glycolipid-I of Mycobacterium leprae induces general suppression of in vitro concanavalin A responses unrelated to leprosy type. J Exp Med. 1987;165:239–244. doi: 10.1084/jem.165.1.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rastogi N, Cadou S, Hellio R. Differential handling of bacterial antigens in macrophages infected with Mycobacterium leprae as studied by immunogold labeling of ultrathin sections. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1991;59:278–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ronot X, Paillason S, Muirhead K A. Assessment of cell viability in mammalian cell lines. In: Al-Rubeai M, Emery A N, editors. Flow cytometry: Applications in cell culture. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 1996. pp. 177–192. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saavedra R, Becerril M A, Dubeaux C, Lippens R, De Vos M-J, Hérion P, Bollen A. Epitopes recognized by human T lymphocytes in the ROP2 protein antigen of Toxoplasma gondii. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3858–3862. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3858-3862.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sweeley C C, Bentley R, Makita M, Wells W W. Gas-liquid chromatography of trimethylsilyl derivatives of sugars and related substances. J Am Chem Soc. 1963;55:2497–2507. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toossi Z, Kleinhenz M E, Ellner J J. Defective interleukin 2 production and responsiveness in human pullmonary tuberculosis. J Exp Med. 1986;163:1162–1172. doi: 10.1084/jem.163.5.1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tórtola M T, Lanéelle M A, Martín-Casabona N. Comparison of two 2,3-diacyl trehalose antigens from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium fortuitum for serology in tuberculosis patients. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1996;3:563–566. doi: 10.1128/cdli.3.5.563-566.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vanham G, Toossi Z, Hirsch C S, Wallis R S, Schwander S K, Rich E A, Ellner J J. Examining a paradox in the pathogenesis of human pulmonary tuberculosis: immune activation and suppression/anergy. Tuberc Lung Dis. 1997;78:145–158. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8479(97)90021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waldeland H, Frenkel J K. Live and killed vaccines against toxoplasmosis in mice. J Parasitol. 1983;69:60–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Waldeland H, Pfefferkorn E R, Frenkel J K. Temperature-sensitive mutants of Toxoplasma gondii: pathogenicity and persistence in mice. J Parasitol. 1983;69:171–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]