Abstract

The tuberculin skin test (TST) is used for the identification of latent tuberculosis (TB) infection (LTBI) but lacks specificity in Mycobacterium bovis BCG-vaccinated individuals, who constitute an increasing proportion of TB patients and their contacts from regions where TB is endemic. In previous studies, T-cell responses to ESAT-6 and CFP-10, M. tuberculosis-specific antigens that are absent from BCG, were sensitive and specific for detection of active TB. We studied 44 close contacts of a patient with smear-positive pulmonary TB and compared the standard screening procedure for LTBI by TST or chest radiographs with T-cell responses to M. tuberculosis-specific and nonspecific antigens. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were cocultured with ESAT-6, CFP-10, TB10.4 (each as recombinant antigen and as a mixture of overlapping synthetic peptides), M. tuberculosis sonicate, purified protein derivative (PPD), and short-term culture filtrate, using gamma interferon production as the response measure. LTBI screening was by TST in 36 participants and by chest radiographs in 8 persons. Nineteen contacts were categorized as TST negative, 12 were categorized as TST positive, and 5 had indeterminate TST results. Recombinant antigens and peptide mixtures gave similar results. Responses to TB10.4 were neither sensitive nor specific for LTBI. T-cell responses to ESAT-6 and CFP-10 were less sensitive for detection of LTBI than those to PPD (67 versus 100%) but considerably more specific (100 versus 72%). The specificity of the TST or in vitro responses to PPD will be even less when the proportion of BCG-vaccinated persons among TB contacts evaluated for LTBI increases.

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a global public health problem with an estimated 3 million deaths and 8 million new cases yearly (14). In countries with a low incidence of TB, timely detection and treatment of latent TB infection (LTBI) in contacts of smear-positive pulmonary TB patients is required for containment of TB in the community, as latently infected persons are the main source of new TB cases (30). The tuberculin skin test (TST) has been used for detection of LTBI for almost a century. Interpretation of a TST result is often complicated in individuals vaccinated with Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) or exposed to environmental mycobacteria due to the occurrence of cross-reactive (false-positive) immune responses to antigens present in tuberculin (protein purified derivative [PPD]) which are shared by those of nontuberculous mycobacteria and BCG (21, 27). In The Netherlands, skin testing is usually not performed in BCG-vaccinated persons, who are instead screened for LTBI by repeated chest radiographs (11). In the United States, in contrast, screening of BCG-vaccinated persons is by skin testing, and the criterion to define a positive test result is not different from that used in non-BCG-vaccinated persons (4). It has been proposed to base the interpretation of the TST in BCG-vaccinated persons on a number of individual and epidemiological parameters (36), but clear and unambiguous cutoff values would be required for routine screening in daily practice. At present, there is no established method to distinguish TST reactions caused by BCG from those caused by infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. There have been efforts to improve the TST, such as in vitro assays for detection of T-cell responses to PPD (22, 24, 38, 41), but any assay using PPD has the same limitation as the TST with regard to cross-reactivity.

A novel diagnostic assay for detection of LTBI that is more specific than the TST and the result of which would not be affected by previous BCG vaccination would be of great practical use, especially in industrialized countries where the number of immigrants originating from areas where TB is endemic has increased over the last decade. Two potential applications of such a test would be contact investigations of smear-positive pulmonary TB cases on the one hand and the screening of immigrant populations on the other. Because PPD lacks the required specificity for the diagnosis of infection with M. tuberculosis, a novel test should preferably be based on antigens present exclusively in the primary pathogenic mycobacteria, M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, and Mycobacterium africanum, but not in nontuberculous mycobacteria or BCG.

The discovery of such M. tuberculosis-specific antigens has become more straightforward since the deciphering of the complete genome of M. tuberculosis (12). Subtractive hybridization led to the identification of RD1, a genomic region which was found to be present in all M. tuberculosis and pathogenic M. bovis strains but lacking in all BCG vaccine strains and almost all environmental mycobacteria (9, 26). Two antigens encoded by RD1 are the early secreted antigenic target 6-kDa protein (ESAT-6) (17, 37) and culture filtrate protein 10 (CFP-10) (10). Animal studies indicated that T-cell responses to ESAT-6 discriminated between cattle infected with M. bovis and cattle sensitized to environmental mycobacteria (32). In humans, T-cell responses to ESAT-6 alone (25, 29, 34, 40) or those to ESAT-6 and CFP-10 (6, 28, 35, 42) were sensitive and specific for detection of active pulmonary or extrapulmonary TB. T-cell responses to a mixture of overlapping peptides of these antigens yielded results similar to those of the intact recombinant antigen (7), indicating that peptides may be easily obtainable alternative diagnostic antigens. At the time this study was initiated, no data were available regarding the use of T-cell responses to these M. tuberculosis-specific antigens for the screening of recent TB contacts.

In order to investigate this issue, we have compared the results of the standard screening procedure by skin testing with T-cell responses to M. tuberculosis-specific and nonspecific antigens in a cohort of healthy contacts of a patient diagnosed with smear-positive pulmonary TB.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

The study subjects were recruited among the contacts of a professional football player with smear-positive cavitary pulmonary TB, diagnosed 31 December 1999. The source patient had been coughing for at least 6 weeks before the diagnosis was made and the contact investigation was started. All participating subjects gave written permission for blood sampling after written information was provided, and the protocol (protocol P136/97) was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Leiden University Medical Center. The non-BCG-vaccinated contacts underwent skin testing using 2 tuberculin units (TU) of tuberculin (type RT23, batch 13971; Statens Serum Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark), and per convention, induration in millimeters was read after 48 to 72 h. The TST was repeated in March 2000, 3 months after the last possible moment of exposure, in contacts with a negative or equivocal first TST result. This interval is generally applied, as skin test conversions have been shown to have occurred within this period (33, 43). All skin testing and reading was performed by experienced personnel of the local Municipal Health Department (Zaanstreek-Waterland, Zaandam, The Netherlands). Three tubes of heparinized venous blood (27 ml) were drawn simultaneously with the screening procedure.

According to common practice in The Netherlands, BCG-vaccinated contacts and those born before 1945 did not undergo skin testing but were instead followed by serial chest radiographs. According to the guidelines of the Royal Netherlands Tuberculosis Association, the TST was regarded as negative if the induration was <2 mm in diameter, as TST positive if it was ≧10 mm in diameter on first testing, as TST conversion in the presence of a negative first TST result and an increase of ≧10 mm on the second TST, or as TST indeterminate if the preceding criteria were not met. LTBI was defined as a positive TST result or TST conversion in the absence of any signs or symptoms of active TB, including a normal chest radiograph, corresponding to class 2 according to the clinical presentation criteria of the American Thoracic Society (4).

Antigens and peptides for in vitro assay.

Recombinant ESAT-6 (rESAT-6; batch P432), rCFP-10 (batch 99-01), and rTB10.4 (batch 99-02) were expressed in Escherichia coli as described previously (10, 17, 35, 37). M. tuberculosis H37Rv sonicate was provided by D. van Soolingen (National Institute of Public Health and the Environment, Bilthoven, The Netherlands). PPD RT44 for in vitro stimulation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) was purchased from the Statens Serum Institute. The production of short-term culture filtrate (ST-CF) has been described previously (3).

Peptides 20 amino acids (aa) long with a 10-aa overlap (for ESAT-6 and CFP-10) or 18 aa long with an 8-aa overlap (for TB10.4) were manufactured by standard solid-phase methods on a Syro II peptide synthesizer (MultiSyntech, Witten, Germany) as described previously (20). The amino acid composition was verified by mass spectometry, and the purity of the peptides was analyzed by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. The amino acid sequences of the peptides of ESAT-6 and CFP-10 have been published previously (7). The sequences of the peptides of TB10.4 (Rv0288) were as follows: peptide 1 (p1), MSQIMYNYPAMLGHAGDM; p2, MLGHAGDMAGYAGTLQSL; p3, YAGTLQSLGAEIAVEQAA; p4, EIAVEQAALQAWQGDTG; p5, SAWQGDTGITYQAWQAQW; p6, YQAWQAQWNQAMEDLVRA; p7, AMEDLVRAYHAMSSTHEA; p8, AMSSTHEANTMAMMARDT; and p9, MAMMARDTAEAAKWGG.

Cellular stimulation assays.

PBMC were isolated from heparinized venous blood by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation. The cells were frozen in RPMI 1640 (Gibco, Paisley, Scotland) supplemented with 0.04 mM glutamine, 20% fetal calf serum, and 10% dimethylsulfoxide until use. Paired cell samples obtained from individuals who donated two blood samples were always tested simultaneously. All data were obtained in four experiments. For cell cultures, PBMC (1.5 × 105/well) were incubated in the presence or absence of antigen in 200 μl of Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (Gibco), supplemented with 10% pooled human AB serum, 40 U of penicillin/ml, and 40 μg of streptomycin/ml in triplicate at 37°C in humidified air containing 5% CO2, using round-bottom microtiter wells. The final concentrations of the antigens, which gave optimal responses in preliminary studies, were as follows: M. tuberculosis sonicate, PPD, and ST-CF, 1 μg/ml each; rESAT-6, rCFP-10, and rTB10.4, 5 μg/ml each. Peptides were used as a mixture of nine overlapping peptides spanning the complete sequence of ESAT-6, CFP-10, or TB10.4. For ESAT-6 and CFP-10, the peptides were used at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml/peptide (9 μg/ml total); for TB10.4, a concentration of 2 μg/ml/peptide (18 μg/ml total) was optimal. Supernatants for gamma interferon (IFN-γ) determination, as the readout of PBMC activation, were collected at day 6 (50 μl/well) and pooled per triplicate. The results of PBMC cultures are hereafter referred to as T-cell responses, because T cells have previously been shown to be the main source of IFN-γ, even though strictly speaking NK cells provide a minor contribution.

IFN-γ production.

IFN-γ was measured with a standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technique (U-CyTech, Utrecht, The Netherlands). The detection limit of the assay was 20 pg of IFN-γ/ml. IFN-γ values in unstimulated cultures were typically undetectable, except in 7 of 76 (9%) unstimulated triplicates with a median concentration of 36 pg/ml. Detectable values were subtracted from the values in stimulated cultures.

Statistical analysis.

Differences between T-cell responses were tested nonparametrically by the Mann-Whitney test for comparison of two groups and by the Kruskal-Wallis test for comparison of more than two groups. The correlation between T-cell responses to different antigens and the correlation between TST responses and T-cell responses to mycobacterial antigens were analyzed nonparametrically by Spearman's correlation. The Hotelling t test was used for comparison of correlation coefficients. All statistical analyses were two sided; P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

TST results of the contact investigation.

Forty-four contacts participated in the study, 41 men and 3 women, with a median age of 24.8 (range, 15.1 to 64.2) years. Two blood samples with a 6-week interval were obtained from 32 contacts. The remaining individuals gave blood only once at the time of the first TST (n = 6) or the second TST (n = 6), resulting in a total of 76 blood samples. Among the contacts were 29 football players who had traveled and trained regularly with the index patient, five trainers, three materials caretakers, one masseur, one physiotherapist, the club physician, and four nonprofessional contacts. Five of the 44 subjects were foreign born, 3 of whom had been BCG vaccinated. One native contact had been BCG vaccinated. Active pulmonary TB was excluded in all participants by chest radiographs. According to the above definitions, 19 persons were categorized as TST negative, 12 were TST positive (3 with a positive first TST, 5 with TST conversion, and 4 with a positive TST at the second time of testing without a first result available), 5 had indeterminate TST responses, and the TST was not performed in 8 persons because of previous BCG vaccination (n = 4), age (n = 3), or a history of pulmonary TB several years previously (n = 1). All individual TST results are shown in Table 1. Treatment with isoniazide was advised for all 12 individuals with LTBI based on a positive TST result, as well as for the 5 persons with indeterminate TST results. Many contacts eligible for early treatment objected to 6 months of medication, fearing adverse effects on their professional sports performance. They were given an alternative regimen consisting of a combination of rifampin and pyrazinamide for 2 months, which is stated in the recent guidelines of the American Thoracic Society (5) to be an acceptable alternative treatment of LTBI in human immunodeficiency virus-negative, skin test-positive individuals.

TABLE 1.

Individual TST results and IFN-γ production by PBMC in response to mycobacterial antigens in 44 contacts of a patient with contagious TB

| Subject no. | TST result (mm of induration at 48 h)

|

IFN-γ production (pg/ml)a

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TST 1

|

TST 2

|

TST 1

|

TST 2

|

|||||||||||

| Complex antigens

|

Recombinant antigens

|

Complex antigens

|

Recombinant antigens

|

|||||||||||

| MTB | PPD | STCF | rESAT6 | rCFP10 | rTB10.4 | MTB | PPD | STCF | rESAT6 | rCFP10 | rTB10.4 | |||

| 1 | NDd | ND | 13,799 | 6,855 | 2,845 | < | < | < | 2,155 | 1,012 | 328 | < | < | 53 |

| 2 | ND | ND | 639 | 360 | 249 | < | < | 252 | 696 | 208 | 247 | < | < | 435 |

| 3 | ND | ND | 3,423 | 1,549 | 1,925 | < | < | 1,699 | 1,699 | 1,365 | 804 | 69 | 34 | 711 |

| 4 | ND | ND | 77 | 89 | < | < | < | < | 280 | 61 | < | < | < | < |

| 5 | ND | ND | 486 | 795 | 312 | < | < | < | 975 | 798 | 192 | < | < | < |

| 6 | ND | ND | 2,205 | 974 | 688 | 68 | 538 | 231 | 1,391 | 1,736 | 725 | 147 | 1,047 | 133 |

| 7 | ND | ND | 243 | 194 | 48 | < | < | 20 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 8 | ND | ND | − | − | − | − | − | − | 229 | 117 | 88 | < | < | < |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 2,124 | 429 | 158 | < | < | < | 776 | 135 | 26 | < | < | < |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 116 | < | < | < | < | < | 477 | 60 | 101 | < | < | < |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 441 | < | < | < | < | < | 366 | 101 | 56 | < | < | 67 |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | < | < | < | < | < | 47 | 34 | 0 | 23 | < | < | 23 |

| 13 | 0 | 0 | < | < | < | 32 | 59 | 42 | < | 37 | 0 | 45 | 53 | < |

| 14 | 0 | 0 | < | < | 27 | < | < | 105 | < | < | 67 | < | < | 288 |

| 15 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 27 | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < |

| 16 | 0 | 0 | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | 25 | < | 28 | < | < |

| 17 | 0 | 0 | < | 23 | < | 22 | 27 | 35 | < | 20 | < | < | 21 | 27 |

| 18 | 0 | 0 | 158 | 389 | < | < | < | < | 169 | 220 | < | < | < | < |

| 19 | 0 | 0 | 709 | 268 | < | < | 297 | < | 35 | < | < | < | < | < |

| 20 | 0 | 0 | < | < | 33 | 21 | < | 21 | < | < | < | < | < | < |

| 21 | 0 | 0 | 67 | 130 | 23 | 21 | 25 | 24 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 22 | 0 | 0 | 45 | 21 | < | < | < | < | < | 47 | < | < | < | < |

| 23 | 0 | 0 | 24 | < | < | < | < | < | 99 | < | < | < | < | < |

| 24 | 0 | 0 | 56 | 96 | < | < | < | 29 | < | 37 | < | < | < | 21 |

| 25 | 0 | 0 | 23 | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < | < |

| 26 | 0 | 0 | 42 | 81 | 31 | < | < | < | 26 | < | < | < | < | < |

| 27 | 0 | 0 | < | < | < | < | < | 110 | < | < | < | < | < | < |

| 28 | 11 | ND | 4,649 | 4,028 | 3,998 | 64 | 1,033 | 219 | 1,362 | 825 | 292 | < | 231 | 53 |

| 29 | 15 | ND | 1,032 | 555 | 2,349 | 2,945 | 4,511 | 6,653 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 30 | 15 | ND | 732 | 1,306 | 113 | < | 61 | 32 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 31 | 12 | ND | 945 | 1,441 | 1,332 | 196 | 288 | 484 | 1,042 | 744 | 614 | 122 | 237 | 318 |

| 32 | ND | 10 | − | − | − | − | − | − | 228 | 742 | 109 | < | < | < |

| 33 | ND | 12 | − | − | − | − | − | − | 2,551 | 4,070 | 4,577 | 271 | 1,080 | 4,070 |

| 34 | ND | 13 | − | − | − | − | − | − | 357 | 249 | 364 | < | < | 193 |

| 35b | 2 | 15 | 6,858 | 4,079 | 3,457 | 88 | 871 | 94 | 2,652 | 1,218 | 610 | < | 63 | 111 |

| 36b | 0 | 12 | 278 | 299 | 185 | < | 39 | < | 678 | 456 | 365 | < | 37 | < |

| 37b | 0 | 18 | 883 | 935 | 53 | 32 | 85 | 59 | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 38b | 0 | 10 | 3,111 | 2,332 | 989 | < | < | < | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 39b | 6 | 25 | 842 | 1,047 | 1,570 | 200 | 836 | 110 | 663 | 969 | 804 | 82 | 969 | 91 |

| 40c | 0 | 7 | 82 | 20 | < | < | < | 37 | 50 | 71 | < | < | < | 224 |

| 41c | 0 | 9 | − | − | − | − | − | − | 54 | 296 | < | < | < | < |

| 42c | 5 | 7 | 844 | 261 | 22 | < | < | 21 | 319 | 56 | < | < | < | < |

| 43c | 8 | 11 | − | − | − | − | − | − | 1,722 | 1,100 | 121 | < | < | 41 |

| 44c | 8 | 8 | 125 | 61 | < | < | < | < | 151 | 36 | < | < | < | < |

MTB, M. tuberculosis sonicate; <, IFN-γ production below the detection level of the ELISA (20 pg/ml); −, no data.

TST conversion.

TST indeterminate.

ND, not done.

T-cell responses to mycobacterial antigens.

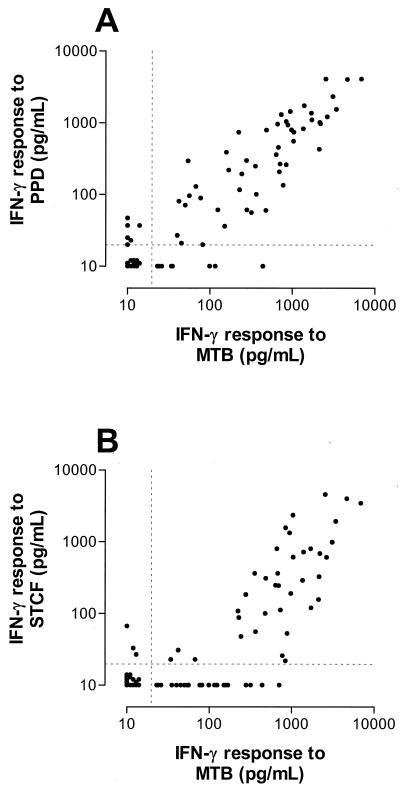

First, we analyzed the correlation among T-cell responses to the different mycobacterial antigens obtained with all 76 blood samples. T-cell responses to M. tuberculosis sonicate were highly correlated with those to PPD (Fig. 1A; r = 0.89; 95% confidence interval [CI]; 0.82 to 0.93; P < 0.0001). Responses to M. tuberculosis sonicate and those to ST-CF were correlated to similar extents (Fig. 1B; r = 0.80; 95% CI, 0.70 to 0.87; P < 0.0001). However, significant responses to ST-CF were found only when responses to M. tuberculosis sonicate exceeded a threshold of about 300 pg of IFN-γ/ml, resulting in the hockey stick-like configuration of the data in Fig. 1B.

FIG. 1.

T-cell responses to M. tuberculosis sonicate (MTB) were significantly correlated with those to PPD (r = 0.89; 95% CI; 0.82 to 0.93; P < 0.0001) (A) and to ST-CF (r = 0.80; 95% CI,0.70 to 0.87; P < 0.0001) (B) in a group of healthy TB contacts evaluated for LTBI. The dashed lines indicate the lower limit of detection of the IFN-γ ELISA (20 pg/ml).

The T-cell responses to each of the three complex antigens were correlated significantly with those to any of the single recombinant antigens (data not shown). The correlation coefficients were lower than those found between responses to the complex antigens, but there was a trend from M. tuberculosis sonicate via PPD to ST-CF towards an increasing correlation with responses to the single antigens. Responses to ST-CF correlated significantly better with those to rESAT-6 than did responses to M. tuberculosis sonicate (Hotelling t test; t = 2.76; P = 0.007), similarly for rTB10.4 (t = 3.55; P = 0.0007), and with borderline significance for rCFP-10 (t = 1.97; P = 0.05).

Responses to recombinant antigens and peptide mixtures.

There was a highly significant correlation between T-cell responses to the recombinant antigens and those to the corresponding peptide mixture for ESAT-6 (r = 0.81; 95% CI; 0.70 to 0.87; P < 0.0001), CFP-10 (r = 0.84; 95% CI; 0.75 to 0.90; P < 0.0001), and TB10.4 (r = 0.74; 95% CI; 0.61 to 0.83; P < 0.0001).

TST results compared with T-cell responses to mycobacterial antigens.

Individual results for the TSTs and T-cell responses are shown in Table 1. Here, we started by comparing all 65 available TST results, as expressed in millimeters of induration, with the corresponding individual level of IFN-γ production by PBMC obtained at the time of that TST in response to an antigen. For each of the antigens tested, the size of the TST result was significantly correlated with the T-cell response (Table 2), the correlation between the TST result and T-cell responses to PPD being highest.

TABLE 2.

Correlations between TST results and T-cell responses to mycobacterial antigens

| Antigen | Spearman r (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| M. tuberculosis sonicate | 0.59 (0.39 to 0.74) | <0.0001 |

| PPD | 0.69 (0.48 to 0.78) | <0.0001 |

| ST-CF | 0.56 (0.35 to 0.72) | <0.0001 |

| rESAT-6 | 0.30 (0.04 to 0.52) | 0.02 |

| rCFP-10 | 0.50 (0.26 to 0.67) | <0.0001 |

| rTB10.4 | 0.44 (0.20 to 0.63) | 0.0005 |

Next, we analyzed the T-cell responses per TST category, now including the group of contacts for whom no TST was performed. In the 32 contacts who donated two blood samples, T-cell responses obtained from paired samples were highly correlated (P < 0.0001 for all antigens). The responses to phytohemagglutinin of paired blood samples were correlated to a similar extent (P < 0.0001), indicating that the cells from both time points had essentially identical response capacities. For the analysis of individual T-cell responses in relation to the TST category, we used the results of the first blood sample, except for six contacts who donated blood only at the time of the second TST. As shown in Fig. 2, T-cell responses to each of the complex antigens were significantly higher in TST-positive contacts and in contacts without TST results available than in the TST-negative contacts. While some TST-negative contacts responded to M. tuberculosis sonicate or PPD, detectable responses to ST-CF were rarely found in this group. T-cell responses to rESAT-6 and/or rCFP-10 were generally undetectable in the TST-negative persons as well as in persons without TST results available, except in the one former TB patient, who had T-cell responses similar to those of the TST-positive individuals. Detectable responses to ≧1 specific antigen were found in 9 of 12 TST-positive contacts. The five contacts with indeterminate TST results had T-cell responses to ST-CF, reSAT-6, and rCFP-10 similar to those of the TST-negative persons. The sensitivity and specificity of the T-cell responses for detection of LTBI were calculated from the results obtained from 12 subjects with and 26 without LTBI, thus excluding the 5 individuals with indeterminate TST results and 1 person with previous active TB. Using a cutoff level of 200 pg of IFN-γ/ml, which was found to be most discriminative in a previous study (6), the sensitivity and specificity were 92 and 68%, respectively, for M. tuberculosis sonicate, 100 and 72%, respectively, for PPD, and 67 and 84%, respectively, for ST-CF. At a cutoff level as low as 60 pg/ml, the individual maximum of the responses to rESAT-6 and rCFP-10 resulted in a sensitivity of 67% and a specificity of 100%. At this cutoff level, the sensitivity and specificity of responses to TB10.4 were 58 and 84%, respectively.

FIG. 2.

T-cell responses to M. tuberculosis sonicate (MTB), PPD, and ST-CF and the individual maximum of the responses to the RD1-encoded antigens ESAT-6 and CFP-10 (RD1-Ag) by category of TST response. The dashed lines indicate the lower limit of detection of the IFN-γ ELISA (20 pg/ml). Statistically significant differences from the group with negative TST results are indicated as follows: #, 0.01 ≤ P < 0.05; ##, 0.001 ≤ P < 0.01; ###, P < 0.001. Comparison of TST-negative persons with other patients with previous TB gave statistically significant differences for all antigens tested (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we compared the routine screening for LTBI in recent TB contacts, using a blood-based assay detecting T-cell responses to various mycobacterial antigens. By definition, LTBI is asymptomatic, and formal proof of the presence or absence of latent infection is not available. In our cohort of recent TB contacts, we regarded the non-BCG-vaccinated persons with a positive TST or TST conversion and without symptoms or radiographic abnormalities as having LTBI. Our results show that T-cell responses to the complex mycobacterial antigens M. tuberculosis sonicate, PPD, and ST-CF were more sensitive but less specific for detection of LTBI than were responses to the M. tuberculosis-specific antigens ESAT-6 and CFP-10. T-cell responses to the recently identified non-M. tuberculosis-specific antigen TB10.4 were neither sensitive nor specific for detection of LTBI, which is in accordance with the presence of the gene encoding TB10.4 (Rv0288) in nontuberculous mycobacteria, including BCG (35).

The high sensitivity associated with the complex antigens is explained by the existing positive correlation between the number of constituent antigens and the height of T-cell responses. However, the majority of antigens present in the complex antigens are common to other mycobacterial species, including BCG and environmental mycobacteria. For example, the T-cell-immunogenic 30- or 31-kDa antigen of M. tuberculosis, also called antigen 85, constitutes up to 45% of the total amount of extracellular proteins yet differs in only a few amino acids from the BCG equivalent (19). Thus, the limited specificity of T-cell responses to the complex antigens is easily explained by the cross-reactive immune responses to common, nonspecific antigens. While very high responses to PPD and ST-CF were not only sensitive but also specific for LTBI in non-BCG-vaccinated contacts, the specificity of responses to the complex antigens decreased considerably after the inclusion of just a few BCG-vaccinated contacts in the group without LTBI. Along this line, it can be expected that the specificity of responses to the complex antigens, such as PPD, will decrease further as the proportion of BCG-vaccinated persons among TB contacts evaluated for LTBI increases. This is likely to occur in all industrialized countries without a BCG vaccination policy, due to the increasing number of BCG-vaccinated immigrants. T-cell responses to ST-CF correlated best with those to the specific antigens, which may be explained by its production process. ST-CF consists of the filtrate of early cultures of M. tuberculosis, lacking cellular breakdown products or heat-denatured proteins. By contrast, the production of PPD involves heat killing of a culture of M. tuberculosis, followed by filtration and precipitation of the proteins. On gel electrophoresis, ST-CF consists of discrete bands along the whole range of molecular weights corresponding to intact exported proteins (2), whereas PPD consists of a smear of degraded proteins in the lower-molecular-weight range (3).

T-cell responses to ESAT-6 and CFP-10 were found exclusively in the non-BCG-vaccinated contacts who were TST positive or had TST conversion and in the only contact who had previously been treated for TB. Responses to ESAT-6 were less frequently detected and were generally lower than those to CFP-10 in latently infected contacts, which could be due to differences in the expression of ESAT-6 and CFP-10 during the early phases of LTBI. It is not clear why one-third of persons with LTBI had undetectable responses to ESAT-6 or CFP-10. It is unlikely that differences in HLA type caused the nonresponsiveness to these antigens in some individuals, as patients with active TB and different HLA types in a previous study were able to respond to the antigens (7). Temporary antigen-specific nonresponsiveness occurs in seriously ill patients with active TB (40, 45, 46, 48), but this is not a recognized phenomenon during the latent phase of infection. We used the TST as the “gold standard” for LTBI, and the possibility that some of the positive TST responses resulted from contact with nontuberculous mycobacteria rather than latent infection with M. tuberculosis could not be excluded.

T-cell responses to all three recombinant antigens were similar to those to corresponding mixtures of synthetic overlapping peptides, as was demonstrated previously for ESAT-6 and CFP-10 in patients with active TB (7). In other studies, peptides of various antigens of M. tuberculosis gave good delayed-type hypersensitivity responses or in vitro T-cell responses (15, 23, 46). Synthetic peptides may allow more widespread evaluation of T-cell responses to M. tuberculosis-specific antigens for diagnosis of active TB or LTBI.

TB will develop in only about 10% of all individuals that are infected with M. tuberculosis in the absence of immune defects. With the present state of knowledge, it is not possible to discriminate persons who have been exposed to M. tuberculosis and who are at risk of active TB from those who have protective immunity. In several studies, the protection conferred by BCG vaccination did not depend on the degree of tuberculin sensitivity induced by the vaccine (8, 13, 16, 18). This is in accordance with a study of BCG-vaccinated mice using adoptive lymphocyte transfer experiments showing that the delayed-type hypersensitivity response and protective immunity are dissociated phenomena, mediated by separate populations of T cells (31). The issue of the relationship between the size of the TST after natural infection with M. tuberculosis and the risk of active TB is not settled (16); methodological differences between studies possibly underlie the conflicting results (1, 44). Parameters for in vitro correlates of protective mycobacterial immunity are being sought (47).

Our study had several limitations. All individuals with LTBI were treated, and some of them might have ultimately progressed to active TB had treatment been withheld. It was therefore not possible to investigate whether the height of T-cell responses to ESAT-6 and CFP-10 was correlated with protective immunity or just the opposite, with the risk of progression to active TB. Next, the number of BCG-vaccinated subjects was low, and skin testing was not performed according to common practice in The Netherlands. Therefore, no parameter for LTBI was available in this group other than the chest radiograph, which is probably of limited value for that purpose. Also, according to the local consensus, we used 2 TU of PPD compared to the 5 TU used in the United States. This may have led to an underestimation of the TST responses, associated with an overestimation of the sensitivity of the ESAT-6- and CFP-10-based T-cell assay. According to the guidelines in The Netherlands, we used ≧10 mm of induration as the criterion for a positive TST result. The most recent guidelines resulting from the official statement of the American Thoracic Society state that a response of ≧5 mm of induration should be considered positive in contacts of a patient with contagious TB (5). Application of this criterion to our data would reclassify the five study subjects with indeterminate TST results as positive. As none of these persons had detectable responses to M. tuberculosis-specific antigens, the sensitivity of such responses would decrease to 47%.

Despite these limitations, RD1-encoded antigens clearly carry the potential for a very high specificity, in accordance with their expression by M. tuberculosis but not by BCG or most environmental mycobacteria (26, 35). This high specificity is a strength justifying further studies to improve the sensitivity of a diagnostic test for detection of TB infection, either through optimization of test conditions or the identification of additional specific antigens encoded by M. tuberculosis-specific genomic regions. Recently, enumeration of IFN-γ-producing cells in response to ESAT-6 by the enzyme-linked immunospot technique could identify 10 of 12 (83%) recently TST-converted contacts of TB patients compared to 0 of 16 uninfected controls (39). This suggests that a very high sensitivity may be reached with the use of M. tuberculosis-specific antigens without loss of specificity. Both patients with active TB and individuals with LTBI can apparently mount T-cell responses to the same M. tuberculosis-specific antigens. Thus, neither the TST nor T-cell responses to specific or nonspecific antigens of M. tuberculosis can as yet differentiate reliably between active TB and LTBI. In that regard, immune responses to antigens that are expressed specifically during latent infection but not during active TB, e.g., isocitrate lyase or α-crystallin (16-kDa antigen), could be evaluated for discrimination between the different phases of TB infection.

We think that the TST will probably remain the most cost-effective and reliable test for detection of LTBI in non-BCG-vaccinated persons in the near future. In view of the limited reliability of the TST in BCG-vaccinated persons, additional studies are required to evaluate the value of a novel diagnostic test using M. tuberculosis-specific antigens in that group. As long as the TST is the only available gold standard for detection of LTBI, the dilemma arises that it is not possible to improve the TST. Further studies could address improvement of the sensitivity, evaluation in BCG-vaccinated persons, identification of additional specific antigens, and technical simplification of the assay. The test should also be evaluated in individuals with impaired T-cell numbers or functions, e.g., as a result of HIV infection or immunosuppressive treatment. The potential applications of a reliable assay for detection of LTBI would not only be the evaluation of recent TB contacts but could include the screening of immigrants from countries with high TB rates. Nowadays, the latter already constitute the majority of TB cases in many industrialized countries.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Commission of the European Communities, the Netherlands Leprosy Foundation, and the Royal Netherlands Tuberculosis Association (KNCV).

We thank all study participants for their cooperation. Karin Jonkers and Krista van Meijgaarden assisted with blood sampling and cell isolation. Ineke Hoeksema, Cilly Hulsing, Jannie Schoen, Marjo Vermeulen, Marion Vorstman, and Annie Zijlmans of the Municipal Health Department in Zaandam were involved with the performance, reading, and registration of the skin tests. Finally, we thank René R. P. de Vries for his continuous support and critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al Zahrani K, Al Hahdali H, Menzies D. Does size matter? Utility of size of tuberculin reactions for the diagnosis of mycobacterial disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:1419–1422. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.4.9912048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen P. Host responses and antigens involved in protective immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Scand J Immunol. 1997;45:115–131. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1997.d01-380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen P, Askgaard D, Ljungqvist L, Bennedsen J, Heron I. Proteins released from Mycobacterium tuberculosis during growth. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1905–1910. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.6.1905-1910.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anonymous. Diagnostic standards and classification of tuberculosis in adults and children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1376–1395. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.4.16141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anonymous. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:S221–S247. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.supplement_3.ats600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arend S M, Andersen P, Van Meijgaarden K E, Skjøt R L V, Subronto Y W, van Dissel J T, Ottenhoff T H M. Detection of active tuberculosis infection by T cell responses to early-secreted antigenic target 6-kDa protein and culture filtrate protein 10. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1850–1854. doi: 10.1086/315448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arend S M, Geluk A, Van Meijgaarden K E, van Dissel J T, Theisen M, Andersen P, Ottenhoff T H M. Antigenic equivalence of human T-cell responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific RD1-encoded protein antigens ESAT-6 and culture filtrate protein 10, and those to mixtures of synthetic peptides. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3314–3321. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3314-3321.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Behr M A, Small P M. Has BCG attenuated to impotence? Nature. 1997;389:133–134. doi: 10.1038/38151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Behr M A, Wilson M A, Gill W P, Salamon H, Schoolnik G K, Rane S, Small P M. Comparative genomics of BCG vaccines by whole-genome DNA microarray. Science. 1999;284:1520–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5419.1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berthet F X, Rasmussen P B, Rosenkrands I, Andersen P, Gicquel B. A Mycobacterium tuberculosis operon encoding ESAT-6 and a novel low-molecular-mass culture filtrate protein (CFP-10) Microbiology. 1998;144:3195–3203. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-11-3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bwire R, Nagelkerke N, Keizer S T, Année-van Bavel J A C M, Sijbrant J, van Burg J L, Borgdorff M W. Tuberculosis screening among immigrants in The Netherlands: what is its contribution to public health? Neth J Med. 2000;56:63–71. doi: 10.1016/s0300-2977(99)00118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cole S T, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon S V, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry III C E, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Quail M A, Rajandream M-A, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Sulston J E, Tayler K, Whitehead S, Barrell B G. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Comstock G W. Identification of an effective vaccine against tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;138:479–480. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/138.2.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dye C, Scheele S, Dolin P, Pathania V, Raviglione M C. Global burden of tuberculosis: estimated incidence, prevalence, and mortality by country. JAMA. 1999;282:677–686. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.7.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elhay M J, Oettinger T, Andersen P. Delayed-type hypersensitivity responses to ESAT-6 and MPT64 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the guinea pig. Infect Immun. 1999;66:3454–3456. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3454-3456.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fine P E, Sterne J A, Ponnighaus J M, Rees R J. Delayed-type hypersensitivity, mycobacterial vaccines and protective immunity. Lancet. 1994;344:1245–1249. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90748-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harboe M, Oettinger T, Wiker H G, Rosenkrands I, Andersen P. Evidence for occurrence of the ESAT-6 protein in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and virulent Mycobacterium bovis and for its absence in Mycobacterium bovis BCG. Infect Immun. 1996;64:16–22. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.16-22.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hart P D, Sutherland I, Thomas J. The immunity conferred by effective BCG and vole bacillus vaccines, in relation to individual variations in induced tuberculin sensitivity and to technical variations in the vaccines. Tubercle. 1967;48:201–210. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harth G, Lee B-Y, Wang J, Clemens D L, Horwitz M A. Novel insights into the genetics, biochemistry, and immunocytochemistry of the 30-kilodalton major extracellular protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3038–3047. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3038-3047.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hiemstra H S, Duinkerken G, Benckhuijsen W E, Amons R, de Vries R R, Roep B O, Drijfhout J W. The identification of CD4+ T cell epitopes with dedicated synthetic peptide libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10313–10318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huebner R E, Schein M F, Bass J B., Jr The tuberculin skin test. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:968–975. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.6.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson P D R, Stuart R L, Grayson M L, Olden D, Clancy A, Ravn P, Andersen P, Britton W J, Rothel J S. Tuberculin-purified protein derivative-, MPT-64-, and ESAT-6-stimulated gamma interferon responses in medical students before and after Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccination and in patients with tuberculosis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:934–937. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.6.934-937.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jurcevic S, Hills A, Pasvol G, Davidson R N, Ivanyi J, Wilkinson R J. T cell responses to a mixture of Mycobacterium tuberculosis peptides with complementary HLA-DR binding profiles. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;105:416–421. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-791.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimura M, Converse P J, Rothel J S, Vlahov D, Comstock G W, Graham N M, Chaisson R E, Bishai W R. Comparison between a whole blood interferon gamma release assay and tuberculin skin testing for detection of tuberculosis infection among patients at risk for tuberculosis exposure. J Infect Dis. 2000;179:1297–1300. doi: 10.1086/314707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lein A D, von Reyn C F, Ravn P, Horsburgh C R, Jr, Alexander L N, Andersen P. Cellular immune responses to ESAT-6 discriminate between patients with pulmonary disease due to Mycobacterium avium complex and those with pulmonary disease due to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:606–609. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.4.606-609.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahairas G G, Sabo P J, Hickey M J, Singh D C, Stover C K. Molecular analysis of genetic differences between Mycobacterium bovis BCG and virulent M. bovis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1274–1282. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1274-1282.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Menzies R I. Tuberculin skin testing. In: Reichman L B, Hershfield E S, editors. Tuberculosis, a comprehensive international approach. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 2000. pp. 279–322. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munk M E, Arend S M, Brock I, Ottenhoff T H, Andersen P. Use of ESAT-6 and CFP-10 antigens for diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:175–176. doi: 10.1086/317663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mustafa A S, Amoudy H A, Wiker H G, Abal A T, Ravn P, Oftung F, Andersen P. Comparison of antigen-specific T-cell responses of tuberculosis patients using complex or single antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Scand J Immunol. 1998;48:535–543. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1998.00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nolan C M. Community-wide implementation of targeted testing for and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:880–887. doi: 10.1086/520453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orme I M, Collins F M. Adoptive protection of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected lung. Dissociation between cells that passively transfer protective immunity and those that transfer delayed-type hypersensitivity to tuberculin. Cell Immunol. 1984;84:113–120. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(84)90082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pollock J M, Andersen P. The potential of the ESAT-6 antigen secreted by virulent mycobacteria for specific diagnosis of tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1251–1254. doi: 10.1086/593686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poulsen A. Some clinical features of tuberculosis. I. Incubation period. Acta Tuberc Scand. 1954;24:311–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ravn P, Demissie A, Eguale T, Wondwosson H, Lein D, Amoudy H A, Mustafa A S, Jensen A K, Holm A, Rosenkrands I, Oftung F, Olobo J, von Reyn F, Andersen P. Human T cell responses to the ESAT-6 antigen from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:637–645. doi: 10.1086/314640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skjøt R L V, Oettinger T, Rosenkrands I, Ravn P, Brock I, Jacobsen S, Andersen P. Comparative evaluation of low-molecular-mass proteins from Mycobacterium tuberculosis identifies members of the ESAT-6 family as immunodominant T-cell antigens. Infect Immun. 2000;68:214–220. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.214-220.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Snider D E., Jr Bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccinations and tuberculin skin tests. JAMA. 1985;253:3438–3439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sørensen A L, Nagai S, Houen G, Andersen P, Andersen Å. Purification and characterization of a low-molecular-mass T-cell antigen secreted by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1710–1717. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1710-1717.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Streeton J A, Desem N, Jones S L. Sensitivity and specificity of a gamma interferon blood test for tuberculosis infection. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1998;2:443–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ulrichs T, Anding P, Porcelli S, Kaufmann S H, Munk M E. Increased numbers of ESAT-6 and purified protein derivative-specific gamma interferon-producing cells in subclinical and active tuberculosis infection. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6073–6076. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.10.6073-6076.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ulrichs T, Munk M E, Mollenkopf H, Behr-Perst S, Colangeli R, Gennaro M L, Kaufmann S H E. Differential T cell responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis ESAT6 in tuberculosis patients and healthy donors. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:3949–3958. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199812)28:12<3949::AID-IMMU3949>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Crevel R, van der Ven-Jongekrijg J, Netea M G, de Lange W, Kullberg B-J, van der Meer J W M. Disease-specific ex vivo stimulation of whole blood for cytokine production: applications in the study of tuberculosis. J Immunol Methods. 1999;222:145–153. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Pinxteren L A H, Ravn P, Agger E M, Pollock J, Andersen P. Diagnosis of tuberculosis based on the two specific antigens ESAT-6 and CFP10. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2000;7:155–160. doi: 10.1128/cdli.7.2.155-160.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wallgren A. The time-table of tuberculosis. Tubercle. 1948;29:245–251. doi: 10.1016/s0041-3879(48)80033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watkins R E, Brennan R, Plant A J. Tuberculin reactivity and the risk of tuberculosis: a review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4:895–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilkinson R J, Haslo̧v K, Rappuoli R, Giovannoni F, Narayanan P R, Desai C R, Vordermeier H M, Paulsen J, Pasvol G, Ivanyi J, Singh M. Evaluation of the recombinant 38-kilodalton antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis as a potential immunodiagnostic reagent. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:553–557. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.3.553-557.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilkinson R J, Vordermeier H M, Wilkinson K A, Sjölund A, Moreno C, Pasvol G, Ivanyi J. Peptide-specific T cell responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis: clinical spectrum, compartmentalization, and effect of chemotherapy. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:760–768. doi: 10.1086/515336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Worku S, Hoft D F. In vitro measurement of protective mycobacterial immunity: antigen-specific expansion of T cells capable of inhibiting intracellular growth of bacille Calmette-Guérin. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(Suppl. 3):S257–S261. doi: 10.1086/313887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Young D B, Garbe T R. Heat shock proteins and antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1998;59:3086–3093. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.3086-3093.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]