Abstract

Aim:

Hydration and well-being are highly correlated. However, practice tells us that the significance of hydration is often unrecognized and is not treated as a priority. This review focuses on how health education can improve hydration levels among the adult population.

Method:

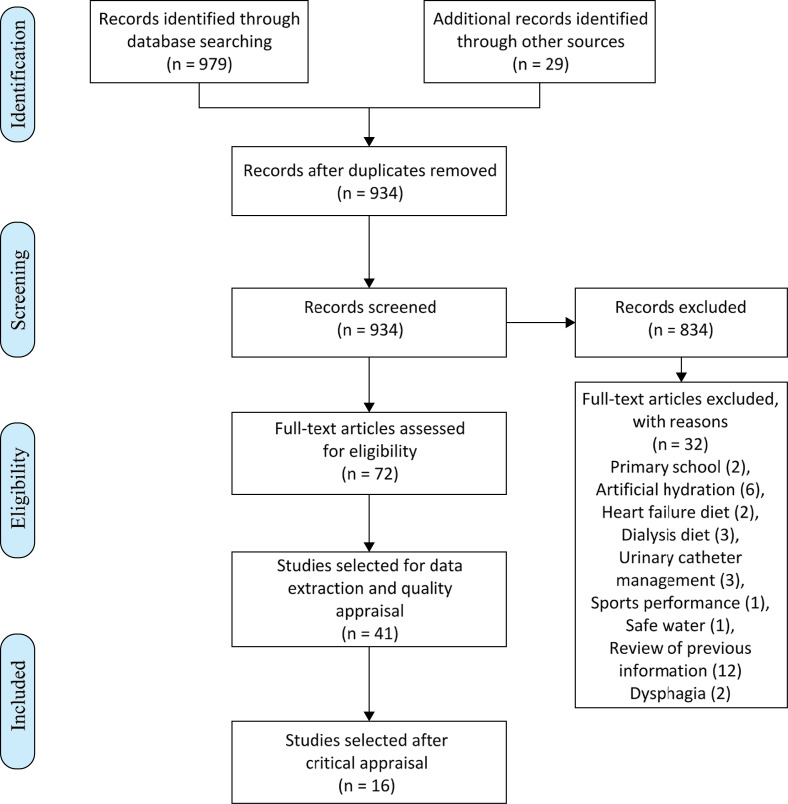

The research question of the study is “Can health promotion improve hydration among adults?” A total of 934 papers were screened using search engines such as CINAHL, COCHRANE, PUBMED, EMBASE, and Google Scholar. Seventy-two articles were assessed for eligibility and 41 of them were selected for quality appraisal using the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) Systematic Review Checklist, which left the study with 16 articles to be fully reviewed and included in the study.

Results:

The findings of the study show that water intervention programs help low-drinker participants to sustainably increase their water intake and maintain their habits through time. There was a sustainable impact on decreasing the number of falls, delirium, and the patient’s dependence, with an improvement in their overall condition.

Conclusion:

Dehydration is associated with increased morbidity and mortality and is an easily preventable condition, but is often overlooked. Public awareness and hydration education is needed to promote healthy habits, a subject in which nurses play a role of paramount importance.

Keywords: Dehydration, health promotion, hydration, nursing, patient education

Introduction

The review question is focused on methods to improve hydration among adults. Health promotion activities have a positive impact on adults’ health and their awareness of the importance of hydration.

Health promotion seeks to enhance the independence of individuals by giving them the knowledge and tools for self-care, to improve their wellbeing by acting on the determinants of health. Good hydration is essential for our health as water is the major component of most of the cells of the body and sustains the equilibrium between them (Benelam & Wyness, 2010).

Educating and implementing health promotion activities related to hydration and diet among our patients would increase their independence and allow them to make informed choices about their health, which could prevent many exacerbations. Raising awareness about the importance of hydration could contribute to their general condition and subsequently minimize the amount of care that is needed from the healthcare services. Implementing these measures could improve the excellence of care by increasing the efficiency, making our services safer and promoting a responsible utilization of the health services (Benelam & Wyness, 2010; Chen et al., 2017).

There is an existing broad range of research studies (de Ridder et al., 2017; Gentile & Weir, 2018; Nyenhuis et al., 2018) related to the importance of diet and how this influences our health. However, even though water is known to play a vital role in our diet, very little research (Archibald, 2006; Konings et al., 2015) focuses on hydration alone. Most research is focused on food and nutrition. There is some research (Archibald, 2006; Bak, 2017; Gomez et al., 2013) done on hydration care in the care homes and hospitals, but it is of poor quality in the vast majority of cases. Furthermore, very little research (Chen et al., 2017; Steven et al., 2019) focuses on whether the strategies of health promotion to improve hydration actually work. Therefore, this study attempts to fill the gap observed in the literature. This topic is of paramount importance to improve the hydration status of the population in an effective, sensible, practical, and evidence-based manner. This will introduce us to the problems that arise in the implementation of hydration strategies and give us a realistic view of why, on many occasions, we fail to encourage people to maintain good health by staying hydrated.

Research Question

Can health promotion improve hydration among adults?

Method

Study Design

A systematic review of the literature was conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., 2009a).

Search Terms

Table 1 shows the different terms that were utilized in this review. These terms were chosen in order to obtain relevant articles that could answer the established research question.

Table 1.

Search Terms

| Search Term 1 Hydration |

Search Term 2 Health Promotion |

|---|---|

| Hydration/dehydration/fluid intake | Health promotion/patient education/health education/patient information |

Search Strategy

The search strategy for term 1 used keywords including “hydrat*”, “dehydrat*”, “fluid intake”, and MeSH terms including “hydration”, “dehydration”, and “fluid intake”. For term 2, the strategy included “health promotion”, “patient education”, “health education”, “patient information”, and the MeSH terms “health promotion”, “patient education”, and “health education”. Truncations were used in order to obtain a broad but accurate result that included studies related to hydration care as well as the role that healthcare professionals play in it. The studies included in this review were obtained utilizing the words and MeSH terms related to term 1, combined with the Boolean connector OR; a second search was conducted with the words and MeSH terms of term 2 combined with OR as well. To finalize, all the results from each search term were combined with AND.

A search of various electronic databases such as CINAHL, COCHRANE, PUBMED/MEDLINE and EMBASE was conducted with the mentioned search strategy. These search engines were selected because they are trustworthy, validated, and of high relevance in the field of healthcare interventions. They provide information that has been thoroughly and systematically reviewed. PUBMED/MEDLINE and EMBASE were chosen as they contain a vast number of life science journals and online books, and were particularly robust in relation to cohort studies and observational studies in hydration promotion. On the other hand, CINAHL and COCHRANE were chosen because they place emphasis on literature relating to nursing and allied health professionals. They were very useful in finding studies that explored the views of patients and caregivers on hydration, and focus on the effectiveness of healthcare interventions to inform decision-making (Linsley et al., 2019). Gray literature was sought through Google Scholar and some journals were used as a feasible source of information such as the British Journal of Nutrition and the Journal of Community Nursing. Various qualitative studies were chosen due to their relevance, to gain an insight into people’s thoughts and opinions regarding hydration and its relevance to our health. They help us identifying which factors contribute or prevent the adult population from staying hydrated.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Articles published in both English and Spanish were sought. The focus was hydration and dehydration related to health promotion and health prevention. The inclusion criteria consisted of peer-reviewed studies on adult humans. The exclusion criteria were intake of fluid to prevent constipation, drinking safe water, fluid intake in sports, artificial hydration, fluid restrictions, and diet in patients with heart failure and those undergoing hemodialysis, and promoting fluid intake in primary schools. No search limits were used for the time of publication of the article, as it was not relevant for the study, it was noticeable that hydration has only gained relevance over the last few years. There was a lack of health promotion studies related to hydration over the past decades.

Search Outcome

The initial search yielded 979 articles and 29 potential articles were found through database search and other source searches respectively. Duplicated records were deleted (n=74), leaving 934 articles for the screening process. After reading the titles and abstracts, 834 articles were excluded since they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The remaining 72 articles were read in full to assess their eligibility, and 32 articles were discarded because they did not comply with the criteria. The remaining papers (n=41) were selected for data extraction and quality appraisal, and 16 articles were selected for inclusion in this review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Chart. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocol.

Quality Appraisal

The systematic review was conducted using the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) checklists as guidance. Each checklist was used in accordance with the type of article that was used in the study, such as systematic reviews, qualitative research, and cohort studies. This was done to ensure the quality, validity, and relevance of the articles. The 16 selected studies were read, and the key points summarized (Table 2).

Table 2.

Features of Included Studies

| Authors | Title | Study Aim | Findings/Conclusion | Limitations/New Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oates and Price (2017) | Clinical assessments and care interventions to promote oral hydration among older patients: a narrative systematic review | Describe clinical assessment tools which identify patients at risk of insufficient oral fluid intake and the impact of simple interventions to promote drinking, in hospital and care home settings | Nine formal hydration assessments were identified, five of which had an accompanying intervention/ care protocol. Interventions to provide extra opportunities to drink such as prompts, preference elicitation and routine beverage carts appeared to support hydration maintenance. Despite a lack of knowledge of fluid requirements and dehydration risk factors among staff, there was no strong evidence that increasing awareness alone would be beneficial for patients. |

Further research is required in interventions to provide extra opportunities to drink. Insufficient evidence to recommend a specific clinical assessment to identify older persons at risk of poor oral fluid intake. |

| Abdallah et al. (2009) | Dehydration reduction in community-dwelling older adults | Investigate dehydration problems among community-dwelling older adults and to identify strategies perceived to be helpful in preventing dehydration in this population. | 89% of participants identify dehydration as a problem affecting older adults, and 94% noted the need for a public campaign on dehydration awareness and reduction. Strategies identified to promote hydration in community-dwelling older adults included community partnerships, community education, community engagement, and interdisciplinary approaches. |

For future research, four major themes emerged: Intentional Avoidance and Caution, Lack of Awareness/Education/Understanding, Poor Access to Fluids, and Social and Environmental Influences. |

| McCarthy and Manning D (2012) | Water for wellbeing: promoting oral hydration in the elderly | Raising awareness of the importance of drinking adequate fluids for good health and the prevention and treatment of bladder and bowel control problems among frail older people. An education kit was promoted and disseminated to residential and community care providers | Individual resources were rated as excellent 16/25 (64%) or good 9/25 (37%). All respondents agreed that the resources provided adequate information to both advise older people on adequate fluid intake and educate staff so they can promote adequate fluid intake to older people. The majority of respondents 20/25 (80%) had used the kit information in a range of ways including staff, client, and carer education. Feedback from users was positive. | One constraint of the project was the limited number of the printed resource kits available, sufficient only sufficient to provide one kit per organization. Further follow-up is needed with organizations and programs to determine to what extent they have integrated the materials into their practice. |

| Chen et al. (2017) | Effects of a dietary self-management program for community-dwelling older adults: a quasi-experimental design | To examine the effectiveness of a 12-week dietary self-management program for salt-, fluid-, fat-, and cholesterol-intake behaviors of community-dwelling older adults and to compare these effects in rural- and urban-dwelling older adults. |

After 12 weeks, the intervention group had significantly better nutritional status and higher internal health locus of control than the control group. Moreover, older rural participants who received the intervention tended toward higher nutritional self-efficacy and internal health locus of control than their urban counterparts. |

The knowledge gained from this study can help stakeholders to recognize the need for healthcare policy to establish effective strategies and sustainable intervention programs for this population, especially those living in rural areas. |

| Gomez et al. (2013) | A water intervention program to improve fluid intake among French women | Assessing the impact of a water intervention program on fluid intake over a 12-month period in free-living conditions. | Water intake and total fluid intake increased by 151% and 84% respectively after 4 weeks. The habit of drinking water was also strengthened. The results show a significant progression in the water intake of the LOW group participants: an increase of 67% between phases 1 and 2 and 154% compared with the baseline. After 12 months, on average, water intake increased significantly compared with the baseline. The same trend is observed for total fluid intake. Ultimately, the LOW group participants reached the intake levels of the HIGH group participants. However, habit strength remained significantly higher in the latter group after 12 months (high group, 33.97; low group, 28.00; P G .05). | Limitations such as sample representativeness, difficulty to disentangle the impacts of water affordance from those of the educational program. Very encouraging results and should drive researchers and practitioners to extend similar programs at a larger scale or to other populations, combining access to water and education. |

| Herke et al. (2018) | Environmental and behavioral modifications for improving food and fluid intake in people with dementia | To assess the effects of environmental or behavioral modifications on food and fluid intake and nutritional status in people with dementia. To assess the adverse consequences or effects of the included interventions. | Due to the quantity and quality of the evidence currently available, we cannot identify any specific environmental or behavioral modifications for improving food and fluid intake in people with dementia. | More and good quality research in the field is needed |

| Konings et al. (2014) | Prevention of dehydration in independently living elderly people at risk: a study protocol of a randomized controlled trial | To compare two interventions to prevent dehydration in elderly people at risk: an educational intervention alone and an educational intervention in combination with a drink reminder device. | The drinker reminder service (Obli) will constantly remind the elderly to drink sufficiently; so, it is believed to be much more effective than education alone, given only at one single instance. This study will improve the knowledge of the effectiveness of interventions designed to prevent dehydration in elderly people. |

Limits: the study does not include patients with kidney or bladder disease or elderly patients living in nursing homes. This includes not using a control group without any intervention, the risk of excessive fluid intake, and the influence of alcohol and coffee intake; it excludes patients with kidney/bladder disease and nursing home residents. |

| Archibald (2006) | Promoting hydration in patients with dementia in healthcare settings | It aims to enhance nurses’ understanding of dehydration in patients with dementia. | Patients with dementia are at a higher risk of morbidity, mortality, and dehydration compared with other older people. Dehydration can be prevented by increasing the patient’s fluid intake by two glasses of fluid per day, which can lead to fewer falls, less frequent urinary infections and laxative prescriptions. |

Not enough information provided |

| Chua et al. (2016) | A systematic review to determine the most effective interventions to increase water intake | To undertake a systematic review to determine the most effective interventions to increase water intake. | The quality of the studies was mostly neutral (63%), with no studies of high quality. Interventions ranged from instruction alone to self-monitoring tools, providing water bottles, and counselling and education. Most interventions successfully increased water intake, with 13 studies reporting an increase of at least 500 mL. The most effective strategies were instruction and self- monitoring using a urine dipstick or 24 h urine volume. |

More high-quality long-term intervention studies are required to further validate findings |

| Benleam & Wyness (2010) | Hydration and health: a review | Increase the Knowledge of hydration and the role of water in our body | Water is essential for life, and maintaining optimum hydration is important for the body to function efficiently |

Not enough information provided |

| Journal of Community Nursing (2014) | The provision of adequate hydration in community patients | Prevent dehydration in the community setting | Hydration is such a basic requirement of good health, but it can be easily overlooked. It is important to monitor patients’ hydration status. | Not enough information provided |

| Feliciano et al. (2010) | Assessment and management of barriers to fluid intake in community-dwelling older adults | To assess factors that are barriers to hydration for two elders using a functional assessment interview | The highest endorsed categories included Knowledge and Skills at 83.3% of items endorsed, Functional Barriers: Mobility at 70% of items endorsed and Preference and Access at 40% of items endorsed. Large increase in consumption of healthy fluids (M = 73.1 oz) and a decrease in consumption of unhealthy fluids (M = 5.6 oz) with the administration of the package intervention when compared to baseline (M = 46.7 oz, M = 19.4 oz, respectively) | Future researchers should consider expanding this model to include greater numbers of elders to increase our knowledge base regarding barriers to hydration. Future research should also include larger numbers of minority elders to assess whether the barriers to hydration are robust or if specific cultural variables may also need to be included in the model. |

| Bak (2017) | Improving hydration of care home residents by addressing institutional barriers to fluid consumption – an improvement project | To assess current hydration care in nursing homes, identify barriers to drinking adequate amounts and develop strategies to optimize fluid intake in the older care home residents. | Observations revealed that most residents consumed less than the recommended minimum of 1500mL of fluids. Hydration not seen as a priority resulted in several barriers that hindered staff ability to serve adequate amounts of fluids, and residents’ enjoyment and ability to consume them. During the testing, most interventions resulted in the residents consuming more fluids, but sustaining these interventions was difficult. Barriers to sustainability included poor leadership and task-oriented work culture. | Limitations: One of the issues identified was the impact of escalating these interventions across the home. Due to time limitations of the project, it was not possible to determine the extent of this problem. Another limitation was the small number of PDSA cycles to ensure successful implementation of the interventions on the new unit. Setting may be considered the greatest limitation of this study. The work was conducted in one large nursing home in London. Future research needs to be done to test different designs of drinking vessels suitable for this population. There is a need for future research to identify appropriate methodologies and describe barriers and facilitators for improving care in this setting and assessing hydration in a wider setting |

| Steven et al. (2019) | The implementation of an innovative hydration monitoring app in care home settings: a qualitative study | The aim of this study was to examine the implementation of Hydr8 in a sample of care homes in one area in England. | Findings suggest that Hydr8 benefits practice and improves staff communication. However, due to technical glitches, the enthusiasm for long-term use was dependent on the resolution of issues. In addition, Hydr8 heightened perceptions of personal accountability, and while managers viewed this as positive, some staff members were apprehensive. | Limitations: The sample was small and restricted to a specific geographical area; therefore, it is not representative of the wider population. The technical issues negatively impacted the use and effectiveness of the Hydr8 app, and technical functionality is necessary before further implementing the app in care homes. Staff interviewed were those who volunteered to participate on the day, and this was the deciding factor in the numbers involved. In addition, some sites (n=2) only implemented the use of the Hydr8 app in specific parts of the care home, and the researchers were not aware of it until data collection took place. The focus of further study needs to encompass multiple aspects of use, including normalization into a daily routine, technical issues experienced, information needed on implementation, residents’ perceptions, and participants’ content and design suggestions. |

| Godfrey et al. (2012) | An exploration of the hydration care of older people: a qualitative study | To understand the complexity of issues associated with the hydration and hydration care of older people. | Health professionals employed several strategies to promote drinking, including verbal prompting, offering choice, placing drinks in older people’s hands, and assisting with drinking. Older people revealed their experience of drinking was diminished by a variety of factors including a limited aesthetic experience and a focus on fluid consumption rather than on drinking as a pleasurable and social experience. Hydration practice, which supports the individual needs of older people, is complex and goes beyond simply ensuring the consumption of adequate fluids. | The different contexts and cultures of the two settings may not have been sufficiently considered in developing the theoretical interpretations. Direct observation may have altered hydration practice during the data collection. The observation of practice was limited to communal areas and did not extend to times when patients were away from the ward or residents were in their own rooms. While the role of nurses and HCAs in hydration care has been explored, the study did not attempt to delineate distinctions in hydration practice relating to type and level of professional qualification. |

| Bhanu et al. (2019) | “I’ve never drunk very much water and I still don’t, and I see no reason to do so”: a qualitative study of the views of community-dwelling older people and carers on hydration in later life | To understand community-dwelling older people and informal carers’ views on hydration in later life and how older people can be supported to drink well. | Concerns about urinary incontinence and knowledge gaps were significant barriers. Consideration of individual taste preference and functional capacity acted as facilitators. Distinct habitual drinking patterns with medications and meals exist among individuals. Many relied on thirst. Older people could be supported to drink well by building upon existing habitual drinking patterns. Individual barriers, facilitators, and tailored education should be considered. | The study recruited a limited number of carers, further research may be needed to fully understand the experience of informal caregivers. Exploring both hydration and nutrition may have affected how participants expressed their views around drinking, and some findings could have been taken out of context. Future research is needed to explore educational models of intervention in public health and primary care to promote healthy drinking for older people. This could include exploring the role of the community’s allied health professionals and understanding older peoples’ perceptions of public health information in the media. |

Results

A small six-month study (Benelam and Wyness, 2010) in two residential care homes revealed that when drinking water was made available and visible, with staff reminding the residents to drink regularly, participants experienced an increased feeling of wellbeing. They had a greater ability able to sleep through the night, felt steadier on their feet, were less dizzy, and experienced an easing of bladder problems. One of the homes involved reported a 50% reduction in falls during the study. Based on the evidence and considering that this has been done in a care home, the available evidence is insufficient to determine whether these results applied to people with dementia. One study (Herke et al., 2018) assessed the effects of environmental or behavioral modifications on food and fluid intake status in people with dementia. After 12 months, people with dementia in the intervention group, who received a nutritional education and nutrition promotion program, had a Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) score of 0.10 points lower than those in the control group who did not participate in a program. However, these results may have some potential bias due to the lack of blinding of the intervention and imprecision due to the small sample size.

One study (Steven et al., 2019) examined the implementation of an innovative hydration-monitoring app, the Hydr8, which was used in various care homes. Some positive outcomes that were reported were the improvement of the staff’s knowledge and understanding of hydration and their heightened awareness of individual preferences. Changes in practice were observed due to raised awareness of the importance of contextual factors and individual differences, increasing person-centered care. Hydr8 was advantageous because it made it possible to view data from a 7-day period, that too remotely, thus increasing the potential for communication between stakeholders.

Another study (Konings et al., 2014) compared two interventions to prevent dehydration in elderly people at risk: an educational intervention and an educational intervention in combination with a drink-reminder device. The latter was much more effective than education alone, which was only given at one single instance. The drink-reminder device served as a constant reminder for the elderly to drink sufficiently which improved their self-sufficiency and allowed them to live independently at home for longer.

Gomez et al. (2013) assessed the impact of a water intervention program on fluid intake over a 12-month period in free living conditions. On average, water intake increased by 163%. The LOW group participants reached the intake levels of the HIGH group participants. However, habit strength remained significantly higher in the latter group. These changes remained in place six months after the end of the program. The results were very promising and showed a significant progression, in addition to the behavioral change becoming habitual. However, results should be considered with caution as the sample was quite small and the screening process made sure that the people participating were motivated enough to make these changes. Furthermore, it may not be possible to generalize and compare this study to other health education programs, because in the mentioned study, the researchers provided home deliveries of bottled water in addition to the educational content, to ensure that water objectives were met. This may potentially be an issue when the participants do not have their water delivered and might be a risk factor influencing their behavior for the long term.

Chua et al. (2015) in their study tried to determine the most effective interventions to increase water intake. These included providing instructions alone, providing self–monitoring tools, providing water bottles, and counseling and education. Most interventions successfully increased water intake, with 13 studies reporting an increase of at least 500 mL. The most effective strategies were instruction and self-monitoring using a urine dipstick or 24h urine volume.

Feliciano et al. (2010), in their study, had an individual meeting to review a tailored version of an educational hand-out that specified a minimum daily fluid goal based on the participant’s weight. It addressed the impact of how individual concerns can affect hydration status (e.g., arthritis, memory problems) and provided simple suggestions for ensuring enough fluids despite these concerns; the participants also received beverage coolers and access recommendations. For both participants, the level of healthy beverage intake increased and unhealthy beverage intake decreased as compared to baseline levels. This positive behavioral change was maintained over time. Although results may not be generalized to the wider population due to the small scale of the study, the conclusions provided were very valuable. What makes it particularly relevant is that participants had an opportunity to interact with the educators and feedback was provided on specific days, which made them slowly change their habits during the study. It also encouraged the participants to reflect on their experience and comment on it. Similarly, Chen et al. (2017) examined the effectiveness of a 12-week dietary self-management program for fluid, salt, and fat consumption, emphasizing healthy eating and focusing on dietary control. While the results showed that the intervention group had significantly better nutritional status and self–efficacy, these need to be considered with caution as not enough evidence was provided during the follow-up process and the feedback provided to participants was unclear.

A “hands-free” hydration plan was introduced for 313 patients in hospital: a bottle was clipped onto the bed with a flexible bite valve hose; patients with greater independence were provided with a plastic sports bottle. As a result, there was a reduction in length of stay, dehydration, and infections.

Oates and Price (2017) studied nursing homes. The results were that regular prompts to drink by a healthcare attendant with or without a beverage cart reduced the frequency of dehydration, as observed by three studies. There was also a reduction in falls, urinary tract infections (UTI), and the use of laxatives. There were small increases in the average daily fluid intake in response to additional verbal prompts, in 81% of the participants, particularly residents with greater cognitive impairment; 21% also required preference elicitation to increase their intake. The use of brightly colored cups and beverages with different tastes and temperatures was well received.

Similarly, Archibald (2006) found that people’s response to verbal cues was influenced significantly by their cognitive status. Those with greater cognitive impairment showed the greatest increases in fluid intake in response to verbal prompts alone. The study also identified that patients with lower levels of cognitive impairment responded better when a choice of drinks was added to the prompt. Drink preference appears to be important in obtaining patient concordance to increase fluids, particularly in patients with milder levels of cognitive impairment. Another important finding was that despite the increase in fluid intake due to the interventions, the fluid intake of the majority of participants was still inadequate, and patients were at risk of chronic dehydration. Some residents reported that they avoided drinking fearing incontinence, which can be addressed by placing the bed near the toilet area, using a commode at night if necessary, and providing an analgesic to control arthritic pain.

This is supported by other studies such as Abdallah et al. (2009), in their study about care provider’s perspectives in reducing dehydration among community-dwelling older adults.; Bak (2017), who explored the institutional barriers that prevented care home residents from staying hydrated; and McCarthy et al. (2012), who analyzed effective strategies to improve oral hydration in the elderly. They noted that educating and involving patients, their families, and care providers on a regular basis was a key facilitating strategy to promote hydration. Some other direct interventions are to provide easy access to fluids by placing containers such as sport bottles and cups, having visitors or care providers encourage and remind older adults to drink, and educating them about Water-rich food that could be substituted for water.

Discussion

As previously mentioned, the objective of this study was to find out whether health promotion can make a difference in improving the hydration status of the elderly. The results are very positive and encouraging as some very simple measures in the daily practice really made a difference. Overall, all the studies reported positive outcomes when health promotion measures were considered, with a marked increase in the total fluid intake as well as water intake. Hydration education also encouraged people to choose healthier beverages and promoted greater awareness of their food choices to maintain good hydration levels. All the studies that provided health education in addition to water supply and personalized hydration equipment had a tremendous impact on their hydration levels. The fact that in those studies, the hydration habits were maintained over time when a follow up was conducted was also very promising.

Other studies, such as “The provision of adequate hydration in community patients” done by the Journal of Community Nursing and Abdallah et al. (2009), emphasized the importance of providing health education and promotion to families and care providers as well as the patients. This was noted to improve their knowledge and awareness as well as their ability to make independent and efficient choices. The participants interviewed in the qualitative studies (Abdallah et al., 2009; Bak, 2017) reported this to be a key factor and felt that regular health promotion and education would benefit their situation; this thought was shared among all the members who were involved in the care (patients, caregivers, families) in some way.

Interestingly, the most marked increases in fluid intake were noticed when verbal and visual prompts such as colored jugs were provided to people with dementia (Herke et al., 2018; Oates et al., 2017). Patients who were more independent responded better to a choice of drinks being added to the prompt (Archibald, 2006).

Water was very often seen as a very personal and social factor. In all the studies, both patients and care providers stated the importance of providing fluids according to the likes and dislikes of each individual. Fluid consumption always increased when an individual was surrounded by other people, which is often seen as an excuse to have a chat. Patients reported certain beverages providing a sense of warmth and happiness as they usually evoked past memories. Fear of incontinence and lack of water accessibility were the most common deterrents to fluid intake in all the studies, which is a factor that can be easily addressed in a cost-effective manner. Some studies reported important increases in water intake with measures as simple as providing a plastic sports bottle, or leaving one clipped onto the bed, or using a hydration monitoring app (Benelam & Wyness, 2010; McCarthy & Manning, 2012; Oates & Price, 2017).

Inadequate hydration is a modifiable and easily preventable risk factor, and is widely associated with harm and increased morbidity and mortality. Early detection and hydration care are paramount for our overall condition; however, it is usually overlooked and it has no validated universal standards of care.

It was noticeable that far more data are available on malnutrition that on hydration. Studies related to hydration were usually of poor quality, which creates gaps in the evidence. More work needs to be done in this field.

Dehydration prevention activities are not always informed by strong evidence, the majority of the studies focus on patients who are already in a negative fluid balance.

Regular hydration for health promotion is very beneficial to patients. However, healthcare providers and families also need to be considered as some patients may be dependent (dementia, depression, poor mobility, etc.); involving them has always been shown to ultimately improve the older adults’ hydration. Visual and verbal prompts have been demonstrated to be very effective in increasing fluid intake in people with dementia.

Health promotion interventions are more effective if barriers such as water accessibility or fear of falls/incontinence are addressed. In addition, the individual’s personal preferences need to be considered to make drinking for hydration a good experience and a pleasurable activity rather than a burden and a functional activity. Thus, interventions will be more effective if tailored to the individual’s specific risk for dehydration. Cognitive assessments are known to be a key factor that needs to be considered.

Fluid consumption can be promoted using meal and medication times to encourage drinking, as that is when people are more willing to drink because it creates a social and positive experience to share with others. Provision of extra opportunities such as a beverage cart in addition to visual and verbal prompts has proven to be highly effective.

The findings of this study reveal that mass outreach is needed to increase public awareness of the risks involved in dehydration and to promote hydration for older adults in the community. Likewise, it shows that a water intervention program helps low-drinker participants to sustainably increase their water intake and maintain their habits through time. Furthermore, good hydration levels showed a decrease in falls and delirium in addition to improving the overall condition and promoting their independence.

The findings suggest that nurses could help increase older adult’s awareness of managing their healthy hydration habits and preventing health problems through self-management programs. Raising awareness of adequate hydration is the first step to begin the process of instigating change in clinical practice. Nursing and healthcare support staff should undergo appropriate training to improve their knowledge on hydration. Research studies provide very encouraging results and should drive researchers and practitioners to conduct health education programs that combine access to water and education at a larger scale, and apply this into their daily practice. There is a potential reduction in cost to health and social care by increasing hydration and there is little research on the direct cost benefit of improving hydration, which is an area still to be explored.

Study Limitations

The strength of this study is its clear focus around the subject of health promotion and hydration. The studies included in the review are mainly qualitative, combined with quasi-experimental and observational studies, which is appropriate considering the research question and aim of the study. The selected databases are relevant and appropriate for the topic under investigation. A critical appraisal was conducted to assess the quality and rigor of the studies, discarding the ones that did not meet the criteria. This, as well as a summary table of the articles, is reflected in Figure 1. A PRISMA flow diagram was used to make sure that the procedure of selecting the articles was rigorous. The information from the study was summarized and conceptually organized based on a thematic analysis, which is appropriate considering the review of the chosen studies. The main limitations of the study were the lack of sufficient evidence on the subject and the poor quality of the current studies related to hydration.

With regard to the the authors studied, the strengths are that some authors consider the impact that water accessibility and affordance have on the study; so in all the studies, water bottles and water equipment were provided to the individuals to minimize the impact of water accessibility. This means that the outcomes that were observed as a result of providing hydration education were trustworthy. All the results of the studies are encouraging, and indicate that the same studies should be done on a larger scale as well, to identify gaps in the evidence and promote future research. Authors are clear and honest in stating when the study lacks evidence, and explain the reasons why. The limitations are that there is no mention of whether the authors searched for unpublished and/or gray literature. Some authors reported that the studies lacked evidence as not enough research has been done in the hydration field and that the results could not be transferred onto other environments or sociodemographic areas, as the population studied was too small. Thus, the representativeness of the results is questionable (Archibald, 2006; Bak et al., 2018; Gomez et al., 2013; Herke et al., 2018).

The findings of some studies have direct implications for current and future clinical practice (Abdallah et al., 2009; Archibald, 2006; Bak et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2017; Oates & Price,2017). Health promotion and health education in hydration have been shown to be effective and paramount in the population’s overall health. After providing education to the individuals as well as their family and care providers, their general condition improved and they were more independent and aware of their health. Hospitals and residential homes reported that with the adequate health education and water accessibility, the number of patients experiencing falls, confusion, and urinary tract infections decreased considerably; the same was observed with length of stay in the hospitals. Overall, the independence of all the individuals improved, and staff had more awareness of the patients who needed to be prompted or supported with the hydration care. These findings strongly support the importance of providing hydration education on a routine basis and the need for hydration awareness to be raised among healthcare workers so that they are encouraged to act as the agents of change of the hydration education in our community.

Conclusion and Recommendations

More work needs to be done in terms of hydration care and education. Healthcare workers constantly need to consider when to provide hydration education and how to apply this to their daily practice. They also need to discuss fears related to being hydrated, such as incontinence and the risk of falls. Moreover, pain levels need to be reviewed to assure that optimal water accessibility is acquired, along with the individual’s mobility.

The stakeholders to consider the results of this research and apply them into their evidence-based daily practice would be nurses and my colleagues in the healthcare sector, as they would be the ones acting as agents of change by conducting water education and dehydration prevention. Personnel from the delivery services would need to ensure that they have a good selection of equipment for hydration support, which could be ordered by our team. Healthcare educators and/or providers of online training should consider providing the guidance and training about hydration to the healthcare staff, as this is not something that is considered in the service. All these initiatives need the support of our area manager, as that would make a big difference into making these strategies and plan of action a reality.

Footnotes

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Declaration of Interests: The author declare that they have no competing interest.

Funding: The author declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- Abdallah L., Remington R., Houde S., Zhan L., Melillo K. D. (2009). Dehydration reduction in community-dwelling older adults: Perspectives of community health care providers. Research in Gerontological Nursing, 2(1), 49–57. 10.3928/19404921-20090101-01) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archibald C. 2006). Promoting hydration in patients with dementia in healthcare settings. Nursing Standard, 20(44), 49–52. 10.7748/ns2006.07.20.44.49.c6561) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak A., Wilson J., Greene C., Tingle A., Tsiami A., Canning D., Loveday H. (2018). 2 Improving hydration of care home residents by addressing institutional barriers to fluid consumption--A quality improvement project. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, 72(Suppl.2), 40+. Retrieved from https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A601551618/HRCA?u=anon~34dd1c47&sid=googleS cholar&xid=d9118be2 [Google Scholar]

- Bhanu C., Avgerinou C., Kharicha K., Bauernfreund Y., Croker H., Liljas A., Rea J., Kirby-Barr M., Hopkins J., Walters K. (2019). ‘I’ve never drunk very much water and I still don’t, and I see no reason to do so’: a qualitative study of the views of community-dwelling older people and carers on hydration in later life. Age Ageing, 49(1), 111–118. 10.1111/nep.12675) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benelam B., Wyness L. (2010). Hydration and health: A review. Nutrition Bulletin, 35(1), 3–25. Retreived from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-3010.2009.01795.x. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Centre for T riple V alue H ealthcare (2019). CASP checklists. CASP - Critical ; Appraisal Skills Programme. Retrieved from https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. H., Huang Y. P., Shao J. H. (2017). Effects of a dietary self-management programme for community-dwelling older adults: A quasi-experimental design. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 31(3), 619–629. 10.1111/scs.12375) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua T. X., Prasad N. S., Rangan G. K., Allman-Farinelli M., Rangan A. M. (2016). A systematic review to determine the most effective interventions to increase water intake. Nephrology (Carlton), 21(10), 860–869. 10.1111/nep.12675) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Ridder D., Kroese F., Evers C., Adriaanse M., Gillebaart M. (2017). Healthy diet: Health impact, prevalence, correlates, and interventions. Psychology and Health, 32(8), 907–941. 10.1080/08870446.2017.1316849) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliciano L., LeBlanc L. A., Feeney B. J. (2010). Assessment and management of barriers to fluid intake in community dwelling older adults. Journal of Behavioral Health and Medicine, 1(1), 3–14. 10.1037/h0100537) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile C. L., Weir T. L. (2018). The gut microbiota at the intersection of diet and human health. Science, 16(362), 776–780. 10.1126/science.aau5812) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey H., Cloete J., Dymond E., Long A. (2012). An exploration of the hydration care of older people: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud, 49(10), 1200–11. 10.1126/science.aau5812) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez P., Mariani S. B., Lambert J. L., Monrozier R. (2013). ‘A Water Intervention Program to Improve Fluid Intakes Among French Women.’, nutrition today. Nutrition Today, 48(4), S40–S42. 10.1097/NT.0b013e3182978888) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herke M., Fink A., Langer G., Wustmann T., Watzke S., Hanff A. M., Burckhardt M. (2018). Environmental and behavioural modifications for improving food and fluid intake in people with dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 7, CD011542. 10.1002/14651858.CD011542.pub2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konings F. J., Mathijssen J. J., Schellingerhout J. M., Kroesbergen I. H., Goede de J., Goor de I. A. (2015). Prevention of Dehydration in Independently Living Elderly People at Risk: A Study Protocol of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Int J Prev Med, 19;6: 103. 10.4103/2008-7802.167617) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A., Altman D. G., Tetzlaff J., Mulrow C., Gøtzsche P. C., Ioannidis J. P. A., Clarke M., Devereaux P. J., Kleijnen J., Moher D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000100. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsley P., Kane R., Barker J. (2019). Evidence-based practice for nurses and healthcare professionals (4th ed, pp. 1–251). London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy S., Manning D. (2012). ‘Water for wellbeing: Promoting oral hydration in the elderly. The Australian and New Zealand Continence Journal, 18(2), 52–56). Retreived from: https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.65234856595459 [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G., & PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta- analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLOS Medicine. Public Library of Science, 6(7), e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutbeam D. 1986). Health promotion glossary. Health Promotion, 1(1), 113–127. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/heapro/article-abstract/1/1/113/565227?redirectedFrom=fulltext 10.1093/heapro/1.1.113) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyenhuis S. M., Dixon A. E., Ma J. (2018). Impact of lifestyle interventions targeting healthy diet, physical activity, and weight loss on asthma in adults: What is the evidence? Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. in Practice, 6(3), 751–763. 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.10.026) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oates L. L. (2017, January 17). Clinical assessments and care interventions to promote oral hydration amongst older patients: a narrative systematic review - BMC Nursing. BioMed Central. Retreived from: https://bmcnurs.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12912-016-0195-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steven A., Wilson G., Young-Murphy L. (2019). The implementation of an innovative hydration monitoring app in care home settings: A qualitative study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 7(1), e9892. 10.2196/mhealth.9892) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The provision of adequate hydration in community patients. (2014). Journal of Community Nursing, 73–77 Retrieved from: https://www.jcn.co.uk/journals/issue/01-2014/article/the-provision-of-adequate-hydration-in-community-patients [Google Scholar]

Content of this journal is licensed under a

Content of this journal is licensed under a