Abstract

Biologically speaking, normal aging is a spontaneous and inevitable process of organisms over time. It is a complex natural phenomenon that manifests itself in the form of degenerative changes in structures and the decline of functions, with diminished adaptability and resistance. Brain aging is one of the most critical biological processes that affect the physiological balance between health and disease. Age-related brain dysfunction is a severe health problem that contributes to the current aging society, and so far, there is no good way to slow down aging. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have inflammation-inhibiting and proliferation-promoting functions. At the same time, their secreted exosomes inherit the regulatory and therapeutic procedures of MSCs with small diameters, allowing high-dose injections and improved therapeutic efficiency. This manuscript describes how MSCs and their derived exosomes promote brain neurogenesis and thereby delay aging by improving brain inflammation.

Keywords: mesenchymal stem cell, exosome, brain aging, cognitive function, inflammation, neurogenesis

Introduction

Aging is a topic that has fascinated scientists and philosophers throughout history (da Costa et al., 2016). As the global population is aging, the prevention of brain aging is a common problem. Aging is associated with a progressive decrease in the effectiveness of mechanisms that maintain homeostasis of the body and its organs and tissues, which leads to an increased risk of various pathologies and death (Isaev et al., 2019). At present, China has entered an aging society, and it is expected that in 2050, 30% of the total population will be over 60 years old, The problem of aging is becoming increasingly severe. It is common in science to think of human aging as a set of characteristics that change over time and to refer to someone as “older” or “younger” (Ferrucci et al., 2018). Brain aging is a significant cause of most neurodegenerative diseases and is often irreversible and lacks an effective treatment, leading to a dramatic decline in quality of life (Poulose et al., 2017). As with other organ systems, brain function gradually declines during the aging, mainly in learning and memory functions (Mattson and Arumugam, 2018). Cognitive dysfunction can be described as an imbalance in the structural and functional organization of the brain at all three levels: the molecular/cellular level, the local circuit level, and the large-scale network level. Each of these levels interacts dynamically with the others and exhibits the characteristics of an open complex system (Birle et al., 2021). Cognitive function is complex and may also be affected by diet, and adequate nutrition is effective in preventing cognitive decline (Martínez García et al., 2018). Therefore, since the development of medicine, scientists have been working to explain the phenomenon of cognitive decline in the elderly.

Some studies point out that age-related cognitive decline is characterized by a considerable reduction or even death of neurons in the brain (Foster, 2006; Wang et al., 2021). In the hippocampus (and perhaps in other brain areas), neuronal death can partially compensated by neuronal generation. However, neuronal production is significantly impaired with age (Isaev et al., 2019). In the adult mammalian hippocampus, new neurons are derived from the stem and progenitor cell divisions, a process known as adult neurogenesis (Cope and Gould, 2019). Neurogenesis occurs throughout life in the ventricular-subventricular zone (V-SVZ) of the lateral ventricles and the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG) (Apple et al., 2017). Neurogenesis plays a critical role in neuroplasticity, brain homeostasis, and central nervous system (CNS) maintenance. It is essential to maintaining cognitive function and repairing damaged brain cells affected by aging and brain disease (Poulose et al., 2017). Adult hippocampal neurogenesis directly impacts cognitive function since hippocampal formation is closely linked to the storage and processing of memory (Bekinschtein et al., 2010; Araki et al., 2021). In recent years, evidence has accumulated that neurogenesis can restore a more youthful state during aging. In addition, increased adult neurogenesis contributes to a variety of human diseases, including cognitive impairment and neurodegenerative diseases (Niklison-Chirou et al., 2020). The appearance of neurodegenerative diseases (including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s) increases exponentially with age (Grimm and Eckert, 2017), so aging is considered to be the most critical risk factor for almost all neurodegenerative diseases (Saha and Sen, 2019).

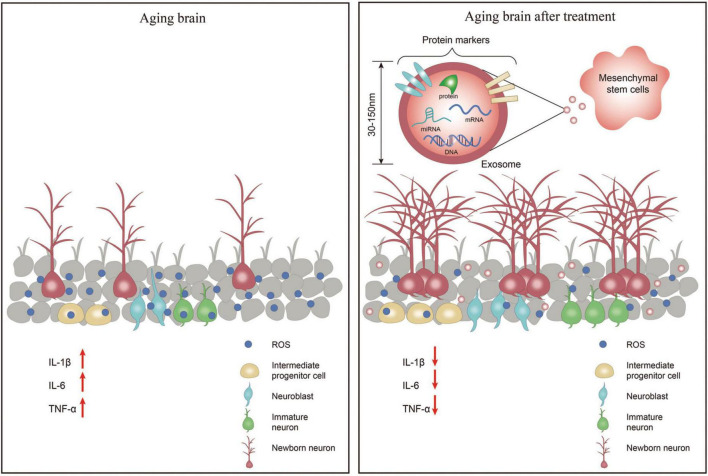

Neurogenic inflammation is triggered by neural activation, resulting in neuropeptide release, rapid plasma extravasation and edema, leading to conditions such as headaches. Neuroinflammation is a local inflammation of the peripheral nervous system (PNS) and CNS (Matsuda et al., 2019). Neuroinflammation has been shown to alter neurogenesis in adults. Various inflammatory components, such as immune cells, cytokines, or chemokines, regulate neural stem cells’ survival, proliferation, and maturation (Sung et al., 2020). During normal brain aging, increased inflammatory activity is caused by the activation of glial cells (Jin et al., 2021). It has been shown that mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) can stimulate neurogenesis and angiogenesis and delay neuronal cell death (Dabrowska et al., 2019). At the same time, their secreted exosomes are smaller in size and cause less immune response in the body, which is a hot topic of current research (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

In the aging brain, the number of neuronal cells is significantly reduced, the levels of inflammatory factors IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α are increased leading to neuroinflammation, and the levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) are increased causing oxidative stress in the brain. After treatment with exosomes secreted by mesenchymal stem cell-extracellular vesicle (MSC-EV), the number of neuronal cells increased, the levels of inflammatory factors IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α decreased, and the levels of ROS decreased thereby reducing oxidative stress in the brain.

Mechanisms and manifestations of brain aging

Cellular senescence is an important factor in tissue deterioration and the accumulation of senescent cells is considered a hallmark of and a pathological cause of aging (Tominaga and Suzuki, 2019). Among the organelles most closely related to senescence is the nucleus (Niedernhofer et al., 2018), mitochondria (Campisi et al., 2019), and lysosomes (Levine and Kroemer, 2019; Wong et al., 2020). The core is mainly involved in the cell cycle, telomere, and epigenomic changes (Pal and Tyler, 2016). A new study finds that age-related epigenetic changes can be reversed by interventions (Kane and Sinclair, 2019); Mitochondria are mainly involved in oxidative stress due to the increase of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), inflammation, and apoptosis (Jang et al., 2018), which are important factors that induce the onset of aging; In lysosomes, it was found that lysosomes and lysosome-related organelles play an important role in the regulation of aging and longevity (Soukas et al., 2019), which is mainly associated with autophagy (Wong et al., 2020); in the cytoplasmic matrix and extracellular, etc., are primarily involved in signaling pathways related to inflammation and fibrosis (Jiang et al., 2017), such as Meschiari et al. (2017) who stated that cardiac fibrosis is usually one of the hallmarks of cardiac aging. These signaling pathways release inflammatory factors and chemokines that contribute to the deterioration of the senescent cells’ microenvironment, which transmits aging signals and affects the transformation of surrounding healthy cells into senescent cells.

The brain is the most complex and vital human organ (Derbyshire, 2018; Hussain et al., 2019; Benito-Kwiecinski and Lancaster, 2020), consuming more energy than any other tissue in proportion to its size. Microstructural degeneration of the gray and white matter in the human brain during aging leads to tissue softening and tissue atrophy (Blinkouskaya et al., 2021). The rate of brain atrophy during aging can predict whether someone will develop cognitive impairment and dementia, and analysis of cross-sectional histological sections suggests that atrophy is the combined result of dendritic regression and neuronal death (Mattson and Arumugam, 2018). Some scholars have used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to find that the frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes decrease with age (Deelchand et al., 2020) while the frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes control language, memory, auditory (Sur and Golob, 2020), motor (Singhal et al., 2020), and attention functions of the human brain. Initially, these aging mechanisms occur mainly at the cellular level due to slowed metabolic activity and ischemia, such as inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction (Stefanatos and Sanz, 2018), oxidative stress (Lushchak, 2021), and calcium dysregulation (Chandran et al., 2019), but then gradually manifest themselves in tissue and eventually organ-level changes in brain shape (Blinkouskaya et al., 2021). In addition, some environmental factors can affect the rate of structural changes in the brain during aging. For example, adequate aerobic exercise increases hippocampal volume, effectively improving memory function (Erickson et al., 2011); overweight and obesity can lead to hippocampal atrophy and affect brain health (Cherbuin et al., 2015).

Mesenchymal stem cell and exosome properties

Mesenchymal stem cells, officially named 29 years ago, represent a class of cells in the human and mammalian bone marrow (BM) and periosteum that can be isolated and expanded in culture while maintaining their ability to be induced to form a variety of different cells in vitro (Caplan, 2017). MSCs have a solid proliferative capacity (Naji et al., 2019) and can self-renew and differentiate into tissue-specific cells (e.g., osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes), and therefore have great potential in regenerative medicine (Samsonraj et al., 2017; Fu et al., 2019). In addition to its pluripotency, MSC has immunomodulatory properties and has been investigated as a potential treatment for various immune diseases (Li and Hua, 2017). MSCs influence most immune effector cells through direct contact with immune cells and local micro-environmental factors. According to studies, the immunomodulatory effects of MSC are mainly delivered through cytokines secreted by MSC. However, apoptotic and metabolically inactivated MSCs have recently shown immunomodulatory potential, with regulatory T cells and monocytes playing a pivotal role (Song et al., 2020). Secondly, since MSCs do not express significant histocompatibility complexes and immunostimulatory molecules, they are not detected by immune surveillance and do not cause graft rejection after transplantation, which is a significant breakthrough point for regenerative medicine (Han et al., 2019). Various animal models (myocardial infarction mice, burned mice, and diabetic mice) and clinical trials have shown that MSCs show good results in repairing damaged tissues (Oh et al., 2018; Selvasandran et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2018). MSCs have the homing ability, which means they can migrate to the site of injury and secrete some growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines that are beneficial for tissue repair (Zhang S. J. et al., 2016; Ullah et al., 2019). Many experimental studies in ischemic stroke have shown that MSCs are able to modulate immune responses and play a neuroprotective role by stimulating neurogenesis, oligodendrogenesis, astrogliogenesis, and angiogenesis. MSCs may also have the ability to replace damaged cells, but paracrine factors released directly into the environment or via extracellular vesicles (EVs) appear to play the most significant role (Dabrowska et al., 2019).

Exosomes are nanoscale vesicles (30–150 nm in diameter) secreted by most cells (Xunian and Kalluri, 2020). They are surrounded by a lipid bilayer and carry a variety of biomolecules, including proteins, lipids, metabolites, RNA, and DNA. When exosomes are taken up by other cells, these exosomes are transferred and affect the phenotype of the recipient cells. Exosomes play a crucial role in bioactive molecule transport, immune response, antigen presentation, protein regulation, cellular homeostasis, and extracellular matrix remodeling (Mori et al., 2019). Thus, exosomes are considered to be an essential mediator of intercellular communication (Wortzel et al., 2019). MSC-derived exosomes contain cytokines, growth factors, lipids, and messenger RNA (mRNA) and regulate microRNAs (miRNAs) function (Phinney and Pittenger, 2017). Exosomes mainly act on the organism in a paracrine manner (Mori et al., 2019), and it has been established that the mode of action of the therapeutic effect of stem cells is mainly paracrine mediated by stem cell secretory factors (Ha et al., 2020), so it is presumed that exosomes primarily act during stem cell therapy. Exosomes have a relative therapeutic effect on a variety of diseases. In a mouse model of acute kidney injury (AKI), MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-Exo) accumulated mainly in inflamed kidneys, whereas in a brain hemorrhage model, MSC-Exo was detected in the injured brain (Harrell et al., 2019). Two proteins commonly found in exosomes, CD81 and tumor susceptibility gene 101 (TSG101), have been confirmed by Western blot (Riazifar et al., 2019; Vakhshiteh et al., 2019). Exosome therapy has shown similar therapeutic effects to direct MSC transplantation without causing multiple adverse outcomes. The complexity of the integrated function of its contents improves the therapeutic effect of MSC-Exo (Zhang B. et al., 2016). Multiple studies have found that after intravenous administration of exosomes, they are predominantly distributed in vascular-rich organs and organs associated with the reticuloendothelial system, such as the liver, lungs, spleen and kidneys (Aimaletdinov and Gomzikova, 2022). In addition, Xu et al. (2020) found that DIR (lipophilic, near-infrared fluorescent anthocyanine dye)-labeled exosomes could be detected in mouse brain after intravenous injection of exosomes by near-infrared fluorescence (NIRF).

Therapeutic effects of mesenchymal stem cells and exosomes on brain aging

Mesenchymal stem cells repair neuronal cells in the hippocampus to slow brain aging

Aging is a natural process; the most obvious outward manifestation accompanying brain aging is a decline in cognitive function. The structure to consider for cognitive decline in the brain is necessarily the hippocampus-a brain region known to play an essential role in learning and memory consolidation as well as in affective behavior and emotion regulation and whose functional and structural plasticity [e.g., neurogenesis (Boldrini et al., 2018)] occurs in adulthood. Neurobiological changes seen in the aging hippocampus, including increased oxidative stress and neuroinflammation, altered intracellular signaling and gene expression, and reduced neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity, are thought to be associated with age-related declines in cognitive function (Bettio et al., 2017). In animal experiments, the Morris water maze is usually used to test the learning memory ability of mice. In contrast, after intracerebroventricular injection of MSC of human BM origin, the aged MSC-treated group showed significant improvements in spatial memory accuracy and prolonged persistence in single- and three-hole target areas as demonstrated in the Morris water maze compared with the aged control group. MSC treatment increased the number of neuroblasts in the hippocampal DG, decreased the number of reactive microglia, and restored presynaptic protein levels compared to older controls. And after MSC transplantation, MSCs mainly migrated to the DG, CA1, and CA3 regions of the hippocampus. Cognitive deficits are associated with altered levels of several neurological factors, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), nerve growth factor (NGF), and glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) (Budni et al., 2015). In contrast, human MSCs express a variety of neuromodulators that promote neuronal survival and neurogenesis (Crigler et al., 2006). We can see this result in the hematoxylin–eosin (HE) pathology and Nissl staining of the MSC-treated and senescent control groups. This experiment concluded that intracerebroventricular injection of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hBM-MSCs) was effective in improving spatial memory in aged rats and that the treatment improved some of the functional and morphological brain characteristics that are typically altered in aging rats (Zappa Villar et al., 2019).

Mesenchymal stem cells slow brain aging by promoting angiogenesis

Gervois et al. (2016) discussed that the neuroprotective effect was mainly attributed to soluble factors secreted by stem cells. Furthermore, it has been shown that stem cells can form vascular structures and secrete pro-angiogenic factors in vitro, positively influencing the growth of blood vessels in vitro and in vivo (Gervois et al., 2016). For example, cerebral ischemia is the most common disease in the elderly (Lappin et al., 2017). Age is the main unmodifiable risk factor for cerebral ischemia. When located in the inflammatory microenvironment in vivo, MSC can release a variety of angiogenic and neurotrophic factors as well as anti-inflammatory molecules; in addition, MSC appears to have an excellent homing ability when administered by systemic routes. Several studies have shown that bone marrow-derived stem cell transplantation in the peripheral circulation improves neurological function and reduces infarct volume. Cellular therapies using MSCs can enhance endogenous repair mechanisms in the damaged brain by supporting the processes of neoangiogenesis, neurogenesis, and neural reorganization. The mechanism by which MSCs improve infarcted brain tissue appears to be more related to the ability of MSCs to release neuroprotective factors (a paracrine mechanism) than to their ability to replace (Sandu et al., 2017).

Mesenchymal stem cells and its secreted exosomes slow brain aging by suppressing the expression of pro-inflammatory factors

Aging is characterized by developing a persistent pro-inflammatory response (Franceschi et al., 2007), and the aging brain is also susceptible to inflammation (Jauhari et al., 2020). Yet, inhibiting of pro-inflammatory factor expression alleviates cognitive impairment in the brain (Yan et al., 2022). Microglia are resident immune cells of the CNS and play a key role in maintaining brain homeostasis (Aguzzi et al., 2013). In the aging brain and neurodegeneration, microglia lose their homeostatic molecular signature and can promote increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Marschallinger et al., 2020). Studies have demonstrated that reactive microglia infiltrate the hippocampus in aging rats and cause it to exhibit an inflammatory state (Pardo et al., 2017). MSC can maintain the resting phenotype of microglia or control microglia activation by producing multiple factors (Yan et al., 2013), thereby controlling the inflammatory response and delaying brain aging. Studies have shown that exosomes obtained from MSC secretion also have anti-inflammatory effects. It regulates the brain infiltration of leukocytes and thus protects the nerves (Wang et al., 2022). Inflammatory responses have long been associated with neurodegenerative processes. And TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, cytokines that support inflammation, are significantly increased in the aging brain. Cui et al. (2019) found that the pro-inflammatory regulators TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 were significantly reduced in the brains of aging mice after MSC-Exo treatment. In the Morris water maze test, the MSC-Exo-treated group significantly reduced escape latency from 3 days after acquisition training, and learning and memory abilities were significantly improved in mice treated with MSC-Exo. Thus, MSC-derived exosomes can rescue memory deficits by modulating the inflammatory response (Cui et al., 2019). Data suggest that MSC-derived exosomes can enter microglia and inhibit their activation to shift them back to function, thereby suppressing inflammation and promoting recovery of brain function (Chen et al., 2020).

Mesenchymal stem cells and its secreted exosomes slow brain aging by promoting neurogenesis

Recent studies have shown the neurogenesis in the adult brain (de Godoy et al., 2018). In addition, the treatment of MSCs has been shown to stimulate neurogenesis in the rat brain and is proposed to be implemented in a number of neurodegenerative diseases (Gobshtis et al., 2017; Kho et al., 2018). Some scientists have also used exosomes secreted by MSCs for treatment and found that exosomes promote neurogenesis in the subventricular zone (SVZ) and DG of the hippocampus and reduce cognitive impairment associated with Parkinson’s disease, stroke, and traumatic brain injury (Yang et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017). From the preceding, it is known that MSC-derived exosomes disrupt the polarization of M1 microglia and trigger their transition to the M2 phenotype, thereby significantly reducing inflammation. In addition, exosome treatment is neuroprotective against oxidative stress and also expands neuronal nerve density (Reza-Zaldivar et al., 2019). Several studies provide evidence that exosomes interact with neurogenic ecotopes through miRNA transfer to neural precursor cells, triggering neural remodeling events, neurogenesis, angiogenesis, and synaptogenesis (Cheng et al., 2018). Some scientists have also modified exosomes with miRNAs. For example, Chen et al. (2021) found that elevated miR-26a enhanced axonal growth in hippocampal neurons and axonal regeneration in the PNS, and then they overexpressed miR-26a in exosomes and found that it could activate the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway to enhance axonal growth and renewal in the nervous system, thus promoting neurogenesis (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Application of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) and exosome in brain aging.

| Type | Mechanism of action | References |

| hBM-MSCs | Improve brain aging by repairing nerve cells in the hippocampus | (Budni et al., 2015) |

| MSCs | Improve brain aging by promoting angiogenesis | (Gervois et al., 2016) |

| MSCs | Maintain the resting phenotype of microglia or 220 control microglia activation by producing multiple factors | (Marschallinger et al., 2020) |

| MSC-Exo | Regulates the brain infiltration of leukocytes and thus protects the nerves | (Pardo et al., 2017) |

| MSC-Exo | Inhibit microglia activation to shift them back to function | (Wang et al., 2022) |

| MSC-Exo | Neuroprotective against oxidative stress and also expands neuronal nerve density | (Zhang et al., 2017) |

| MSC-Exo | Overexpressed miR-26a in exosomes could activate the mTOR pathway to enhance axonal growth and renewal in the nervous system, thus promoting neurogenesis | (Reza-Zaldivar et al., 2019) |

Discussion

Based on the data collected, it is known that brain aging subsequently increases the incidence of neurodegenerative diseases, which seriously affect the quality of life of the elderly. Scientists have been seeking better ways to slow down aging, and MSCs and their derived exosome therapies are emerging promising strategies for treating various diseases. In recent years, there has been increasing research interest in exosomes, their innate ability to transport genetic material, protect it from cellular degeneration, and deliver it to recipient cells in a highly selective manner, suggesting that MSC-derived exosomes are an ideal delivery system for small molecules and a means of gene therapy for cancer treatment and potentially regenerative drugs. In addition, encouraging preclinical data suggest that MSC-derived exosome therapies may be superior to cell-based therapies in terms of safety and versatility. Today, the preparation of MSCs has become proficient and the extraction of exosomes is being refined. However, the technology for purification of exosomes after extraction still needs to be addressed. Furthermore, the progression of exosomes on tumors has been widely reported in the last decade or so. For example, MSC-derived exosomes from bone marrow (BM MSCs) stimulate the hedgehog signaling pathway in osteosarcoma and gastric cancer cell lines, thereby promoting tumor growth (Vakhshiteh et al., 2019). Therefore, the translation of therapies from the laboratory to the clinic requires a clear understanding of component characterization, immune response, etc., in order to optimize their clinical application.

Author contributions

JJ and XW contributed to the conception and design. XZ wrote the manuscript and figure. XH collected the data and designed the figure. LT and ZZ performed literature search and provided valuable comments. All authors contributed to the article and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Aguzzi A., Barres B. A., Bennett M. L. (2013). Microglia: Scapegoat, saboteur, or something else? Science 339 156–161. 10.1126/science.1227901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aimaletdinov A. M., Gomzikova M. O. (2022). Tracking of extracellular vesicles’ biodistribution: New methods and approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23:11312. 10.3390/ijms231911312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apple D. M., Solano-Fonseca R., Kokovay E. (2017). Neurogenesis in the aging brain. Biochem. Pharmacol. 141 77–85. 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.06.116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki T., Ikegaya Y., Koyama R. (2021). The effects of microglia- and astrocyte-derived factors on neurogenesis in health and disease. Eur. J. Neurosci. 54 5880–5901. 10.1111/ejn.14969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekinschtein P., Katche C., Slipczuk L., Gonzalez C., Dorman G., Cammarota M., et al. (2010). Persistence of long-term memory storage: New insights into its molecular signatures in the hippocampus and related structures. Neurotox Res. 18 377–385. 10.1007/s12640-010-9155-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benito-Kwiecinski S., Lancaster M. A. (2020). Brain organoids: Human neurodevelopment in a dish. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 12:a035709. 10.1101/cshperspect.a035709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettio L. E. B., Rajendran L., Gil-Mohapel J. (2017). The effects of aging in the hippocampus and cognitive decline. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 79 66–86. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.04.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birle C., Slavoaca D., Balea M., Livint Popa L., Muresanu I., Stefanescu E., et al. (2021). Cognitive function: Holarchy or holacracy? Neurol. Sci. 42 89–99. 10.1007/s10072-020-04737-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blinkouskaya Y., Caçoilo A., Gollamudi T., Jalalian S., Weickenmeier J. (2021). Brain aging mechanisms with mechanical manifestations. Mech. Ageing Dev. 200:111575. 10.1016/j.mad.2021.111575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldrini M., Fulmore C. A., Tartt A. N., Simeon L. R., Pavlova I., Poposka V., et al. (2018). Human hippocampal neurogenesis persists throughout aging. Cell Stem Cell 22 588–599.e5. 10.1016/j.stem.2018.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budni J., Bellettini-Santos T., Mina F., Garcez M. L., Zugno A. I. (2015). The involvement of BDNF, NGF and GDNF in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Dis. 6 331–341. 10.14336/AD.2015.0825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi J., Kapahi P., Lithgow G. J., Melov S., Newman J. C., Verdin E. (2019). From discoveries in ageing research to therapeutics for healthy ageing. Nature 571 183–192. 10.1038/s41586-019-1365-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan A. I. (2017). Mesenchymal stem cells: Time to change the name! Stem Cells Transl. Med. 6 1445–1451. 10.1002/sctm.17-0051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran R., Kumar M., Kesavan L., Jacob R. S., Gunasekaran S., Lakshmi S., et al. (2019). Cellular calcium signaling in the aging brain. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 95 95–114. 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2017.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Li J., Ma B., Li N., Wang S., Sun Z., et al. (2020). MSC-derived exosomes promote recovery from traumatic brain injury via microglia/macrophages in rat. Aging (Albany NY) 12 18274–18296. 10.18632/aging.103692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Tian Z., He L., Liu C., Wang N., Rong L., et al. (2021). Exosomes derived from miR-26a-modified MSCs promote axonal regeneration via the PTEN/AKT/mTOR pathway following spinal cord injury. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 12:224. 10.1186/s13287-021-02282-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X., Zhang G., Zhang L., Hu Y., Zhang K., Sun X., et al. (2018). Mesenchymal stem cells deliver exogenous miR-21 via exosomes to inhibit nucleus pulposus cell apoptosis and reduce intervertebral disc degeneration. J. Cell Mol. Med. 22 261–276. 10.1111/jcmm.13316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherbuin N., Sargent-Cox K., Fraser M., Sachdev P., Anstey K. J. (2015). Being overweight is associated with hippocampal atrophy: The PATH through life study. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 39 1509–1514. 10.1038/ijo.2015.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cope E. C., Gould E. (2019). Adult neurogenesis, glia, and the extracellular matrix. Cell Stem Cell 24 690–705. 10.1016/j.stem.2019.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crigler L., Robey R. C., Asawachaicharn A., Gaupp D., Phinney D. G. (2006). Human mesenchymal stem cell subpopulations express a variety of neuro-regulatory molecules and promote neuronal cell survival and neuritogenesis. Exp. Neurol. 198 54–64. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui G.-H., Guo H.-D., Li H., Zhai Y., Gong Z.-B., Wu J., et al. (2019). RVG-modified exosomes. Immun. Ageing 16:10. 10.1186/s12979-019-0150-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Costa J. P., Vitorino R., Silva G. M., Vogel C., Duarte A. C., Rocha-Santos T. (2016). A synopsis on aging-theories, mechanisms and future prospects. Ageing Res. Rev. 29 90–112. 10.1016/j.arr.2016.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabrowska S., Andrzejewska A., Lukomska B., Janowski M. (2019). Neuroinflammation as a target for treatment of stroke using mesenchymal stem cells and extracellular vesicles. J. Neuroinflamm. 16:178. 10.1186/s12974-019-1571-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Godoy M. A., Saraiva L. M., de Carvalho L. R. P., Vasconcelos-Dos-Santos A., Beiral H. J. V., Ramos A. B., et al. (2018). Mesenchymal stem cells and cell-derived extracellular vesicles protect hippocampal neurons from oxidative stress and synapse damage induced by amyloid-β oligomers. J. Biol. Chem. 293 1957–1975. 10.1074/jbc.M117.807180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deelchand D. K., McCarten J. R., Hemmy L. S., Auerbach E. J., Eberly L. E., Marjañska M. (2020). Changes in the intracellular microenvironment in the aging human brain. Neurobiol. Aging 95 168–175. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2020.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derbyshire E. (2018). Brain health across the lifespan: A systematic review on the role of omega-3 fatty acid supplements. Nutrients 10:1094. 10.3390/nu10081094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson K. I., Voss M. W., Prakash R. S., Basak C., Szabo A., Chaddock L., et al. (2011). Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 3017–3022. 10.1073/pnas.1015950108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrucci L., Levine M. E., Kuo P.-L., Simonsick E. M. (2018). Time and the metrics of aging. Circ. Res. 123 740–744. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.312816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster T. C. (2006). Biological markers of age-related memory deficits: Treatment of senescent physiology. CNS Drugs 20 153–166. 10.2165/00023210-200620020-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi C., Capri M., Monti D., Giunta S., Olivieri F., Sevini F., et al. (2007). Inflammaging and anti-inflammaging: A systemic perspective on aging and longevity emerged from studies in humans. Mech. Ageing Dev. 128:105. 10.1016/j.mad.2006.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X., Liu G., Halim A., Ju Y., Luo Q. (2019). Song, and guanbin, mesenchymal stem cell migration and tissue repair. Cells 8:784. 10.3390/cells8080784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gervois P., Wolfs E., Ratajczak J., Dillen Y., Vangansewinkel T., Hilkens P., et al. (2016). Stem cell-based therapies for ischemic stroke: Preclinical results and the potential of imaging-assisted evaluation of donor cell fate and mechanisms of brain regeneration. Med. Res. Rev. 36 1080–1126. 10.1002/med.21400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobshtis N., Tfilin M., Wolfson M., Fraifeld V. E., Turgeman G. (2017). Transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells reverses behavioural deficits and impaired neurogenesis caused by prenatal exposure to valproic acid. Oncotarget 8 17443–17452. 10.18632/oncotarget.15245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm A., Eckert A. (2017). Brain aging and neurodegeneration: From a mitochondrial point of view. J. Neurochem. 143 418–431. 10.1111/jnc.14037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha D. H., Kim H.-K., Lee J., Kwon H. H., Park G.-H., Yang S. H., et al. (2020). Mesenchymal stem/stromal cell-derived exosomes for immunomodulatory therapeutics and skin regeneration. Cells 9:1157. 10.3390/cells9051157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y., Li X., Zhang Y., Han Y., Chang F., Ding J. (2019). Mesenchymal stem cells for regenerative medicine. Cells 8:886. 10.3390/cells8080886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell C. R., Jovicic N., Djonov V., Arsenijevic N., Volarevic V. (2019). Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes and other extracellular vesicles as new remedies in the therapy of inflammatory diseases. Cells 8:1605. 10.3390/cells8121605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain G., Wang J., Rasul A., Anwar H., Imran A., Qasim M., et al. (2019). Role of cholesterol and sphingolipids in brain development and neurological diseases. Lipids Health Dis. 18:26. 10.1186/s12944-019-0965-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaev N. K., Stelmashook E. V., Genrikhs E. E. (2019). Neurogenesis and brain aging. Rev. Neurosci. 30 573–580. 10.1515/revneuro-2018-0084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang J. Y., Blum A., Liu J., Finkel T. (2018). The role of mitochondria in aging. J. Clin. Invest. 128 3662–3670. 10.1172/JCI120842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jauhari A., Baranov S. V., Suofu Y., Kim J., Singh T., Yablonska S., et al. (2020). Melatonin inhibits cytosolic mitochondrial DNA-induced neuroinflammatory signaling in accelerated aging and neurodegeneration. J. Clin. Invest. 130 3124–3136. 10.1172/JCI135026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S., Li T., Yang Z., Yi W., Di S., Sun Y., et al. (2017). AMPK orchestrates an elaborate cascade protecting tissue from fibrosis and aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 38 18–27. 10.1016/j.arr.2017.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin W.-N., Shi K., He W., Sun J.-H., Van Kaer L., Shi F.-D., et al. (2021). Neuroblast senescence in the aged brain augments natural killer cell cytotoxicity leading to impaired neurogenesis and cognition. Nat. Neurosci. 24 61–73. 10.1038/s41593-020-00745-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane A. E., Sinclair D. A. (2019). Epigenetic changes during aging and their reprogramming potential. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 54 61–83. 10.1080/10409238.2019.1570075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kho A. R., Kim O. J., Jeong J. H., Yu J. M., Kim H. S., Choi B. Y., et al. (2018). Administration of placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells counteracts a delayed anergic state following a transient induction of endogenous neurogenesis activity after global cerebral ischemia. Brain Res. 1689 63–74. 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappin J. M., Darke S., Farrell M. (2017). Stroke and methamphetamine use in young adults: A review. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 88 1079–1091. 10.1136/jnnp-2017-316071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B., Kroemer G. (2019). Biological functions of autophagy genes: A disease perspective. Cell 176 11–42. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.09.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N., Hua J. (2017). Interactions between mesenchymal stem cells and the immune system. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 74 2345–2360. 10.1007/s00018-017-2473-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lushchak V. I. (2021). Interplay between bioenergetics and oxidative stress at normal brain aging. Aging as a result of increasing disbalance in the system oxidative stress-energy provision. Pflugers Arch. 473 713–722. 10.1007/s00424-021-02531-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschallinger J., Iram T., Zardeneta M., Lee S. E., Lehallier B., Haney M. S., et al. (2020). Lipid-droplet-accumulating microglia represent a dysfunctional and proinflammatory state in the aging brain. Nat. Neurosci. 23 194–208. 10.1038/s41593-019-0566-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez García R. M., Jiménez Ortega A. I., ópez Sobaler A. M. L., Ortega R. M. (2018). [Nutrition strategies that improve cognitive function]. Nutr. Hosp. 35 16–19. 10.20960/nh.2281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda M., Huh Y., Ji R.-R. (2019). Roles of inflammation, neurogenic inflammation, and neuroinflammation in pain. J. Anesth. 33 131–139. 10.1007/s00540-018-2579-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson M. P., Arumugam T. V. (2018). Hallmarks of brain aging: Adaptive and pathological modification by metabolic states. Cell Metab. 27 1176–1199. 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meschiari C. A., Ero O. K., Pan H., Finkel T., Lindsey M. L. (2017). The impact of aging on cardiac extracellular matrix. Geroscience 39 7–18. 10.1007/s11357-017-9959-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori M. A., Ludwig R. G., Garcia-Martin R., Brandão B. B., Kahn C. R. (2019). Extracellular miRNAs: From biomarkers to mediators of physiology and disease. Cell Metab. 30 656–673. 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.07.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naji A., Eitoku M., Favier B., Deschaseaux F., Rouas-Freiss N., Suganuma N. (2019). Biological functions of mesenchymal stem cells and clinical implications. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 76 3323–3348. 10.1007/s00018-019-03125-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedernhofer L. J., Gurkar A. U., Wang Y., Vijg J., Hoeijmakers J. H. J., Robbins P. D. (2018). Nuclear genomic instability and aging. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 87 295–322. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062917-012239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niklison-Chirou M. V., Agostini M., Amelio I., Melino G. (2020). Regulation of adult neurogenesis in mammalian brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:4869. 10.3390/ijms21144869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh E. J., Lee H. W., Kalimuthu S., Kim T. J., Kim H. M., Baek S. H., et al. (2018). In vivo migration of mesenchymal stem cells to burn injury sites and their therapeutic effects in a living mouse model. J. Control Release 279 79–88. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal S., Tyler J. K. (2016). Epigenetics and aging. Sci. Adv. 2:e1600584. 10.1126/sciadv.1600584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo J., Abba M. C., Lacunza E., Francelle L., Morel G. R., Outeiro T. F., et al. (2017). Identification of a conserved gene signature associated with an exacerbated inflammatory environment in the hippocampus of aging rats. Hippocampus 27 435–449. 10.1002/hipo.22703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney D. G., Pittenger M. F. (2017). Concise review: MSC-derived exosomes for cell-free therapy. Stem Cells 35 851–858. 10.1002/stem.2575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulose S. M., Miller M. G., Scott T., Shukitt-Hale B. (2017). Nutritional factors affecting adult neurogenesis and cognitive function. Adv. Nutr. 8 804–811. 10.3945/an.117.016261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reza-Zaldivar E. E., Hernández-Sapiéns M. A., Gutiérrez-Mercado Y. K., Sandoval-Ávila S., Gomez-Pinedo U., árquez-Aguirre A. L. M., et al. (2019). Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes promote neurogenesis and cognitive function recovery in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Regen. Res. 14 1626–1634. 10.4103/1673-5374.255978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riazifar M., Mohammadi M. R., Pone E. J., Yeri A., Lässer C., Segaliny A. I., et al. (2019). Stem cell-derived exosomes as nanotherapeutics for autoimmune and neurodegenerative disorders. ACS Nano 13 6670–6688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha P., Sen N. (2019). Tauopathy: A common mechanism for neurodegeneration and brain aging. Mech. Ageing Dev. 178 72–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samsonraj R. M., Raghunath M., Nurcombe V., Hui J. H., van Wijnen A. J., Cool S. M. (2017). Concise review: Multifaceted characterization of human mesenchymal stem cells for use in regenerative medicine. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 6 2173–2185. 10.1002/sctm.17-0129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandu R. E., Balseanu A. T., Bogdan C., Slevin M., Petcu E., Popa-Wagner A. (2017). Stem cell therapies in preclinical models of stroke. Is the aged brain microenvironment refractory to cell therapy? Exp. Gerontol. 94 73–77. 10.1016/j.exger.2017.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvasandran K., Makhoul G., Jaiswal P. K., Jurakhan R., Li L., Ridwan K., et al. (2018). Factor-α and hypoxia-induced secretome therapy for myocardial repair. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 105 715–723. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal G., Morgan J., Jawahar M. C., Corrigan F., Jaehne E. J., Toben C., et al. (2020). Effects of aging on the motor, cognitive and affective behaviors, neuroimmune responses and hippocampal gene expression. Behav. Brain Res. 383:112501. 10.1016/j.bbr.2020.112501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song N., Scholtemeijer M., Shah K. (2020). Mesenchymal stem cell immunomodulation: Mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 41 653–664. 10.1016/j.tips.2020.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soukas A. A., Hao H., Wu L. (2019). Metformin as anti-aging therapy: Is it for everyone? Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 30 745–755. 10.1016/j.tem.2019.07.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanatos R., Sanz A. (2018). The role of mitochondrial ROS in the aging brain. FEBS Lett. 592 743–758. 10.1002/1873-3468.12902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung P.-S., Lin P.-Y., Liu C.-H., Su H.-C., Tsai K.-J. (2020). Neuroinflammation and neurogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease and potential therapeutic approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:701. 10.3390/ijms21030701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sur S., Golob E. J. (2020). Neural correlates of auditory sensory memory dynamics in the aging brain. Neurobiol. Aging 88 128–136. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.12.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga K., Suzuki H. I. (2019). TGF-β signaling in cellular senescence and aging-related pathology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:5002. 10.3390/ijms20205002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullah M., Liu D. D., Thakor A. S. (2019). Mesenchymal stromal cell homing: Mechanisms and strategies for improvement. iScience 15 421–438. 10.1016/j.isci.2019.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vakhshiteh F., Atyabi F., Ostad S. N. (2019). Mesenchymal stem cell exosomes: A two-edged sword in cancer therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 14 2847–2859. 10.2147/IJN.S200036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Börger V., Mohamud Yusuf A., Tertel T., Stambouli O., Murke F., et al. (2022). Postischemic neuroprotection associated with anti-inflammatory effects by mesenchymal stromal cell-derived small extracellular vesicles in aged mice. Stroke 53 e14–e18. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.035821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Li R., Yuan Y., Zhu M., Liu Y., Jin Y., et al. (2021). PTENα is responsible for protection of brain against oxidative stress during aging. FASEB J. 35:e21943. 10.1096/fj.202100753R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong S. Q., Kumar A. V., Mills J., Lapierre L. R. (2020). Autophagy in aging and longevity. Hum. Genet. 139 277–290. 10.1007/s00439-019-02031-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wortzel I., Dror S., Kenific C. M., Lyden D. (2019). Exosome-mediated metastasis: Communication from a distance. Dev. Cell 49 347–360. 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu R., Bai Y., Min S., Xu X., Tang T., Ju S. (2020). In vivo monitoring and assessment of exogenous mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes in mice with ischemic stroke by molecular imaging. Int. J. Nanomed. 15 9011–9023. 10.2147/IJN.S271519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T., Lv Z., Chen Q., Guo M., Wang X., Huang F. (2018). Vascular endothelial growth factor over-expressed mesenchymal stem cells-conditioned media ameliorate palmitate-induced diabetic endothelial dysfunction through PI-3K/AKT/m-TOR/eNOS and p38/MAPK signaling pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 106 491–498. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.06.129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xunian Z., Kalluri R. (2020). Biology and therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes. Cancer Sci. 111 3100–3110. 10.1111/cas.14563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan F., Tian Y., Huang Y., Wang Q., Liu P., Wang N., et al. (2022). Xi-Xian-Tong-Shuan capsule alleviates vascular cognitive impairment in chronic cerebral hypoperfusion rats by promoting white matter repair, reducing neuronal loss, and inhibiting the expression of pro-inflammatory factors. Biomed. Pharmacother. 145:112453. 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan K., Zhang R., Sun C., Chen L., Li P., Liu Y., et al. (2013). Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells maintain the resting phenotype of microglia and inhibit microglial activation. PLoS One 8:e84116. 10.1371/journal.pone.0084116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Zhang X., Chen X., Wang L., Yang G. (2017). Exosome mediated delivery of miR-124 promotes neurogenesis after ischemia. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 7 278–287. 10.1016/j.omtn.2017.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zappa Villar M. F., Lehmann M., García M. G., Mazzolini G., Morel G. R., Cónsole G. M., et al. (2019). Mesenchymal stem cell therapy improves spatial memory and hippocampal structure in aging rats. Behav. Brain Res. 374:111887. 10.1016/j.bbr.2019.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Yeo R. W. Y., Tan K. H., Lim S. K. (2016). Focus on extracellular vesicles: Therapeutic potential of stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17:174. 10.3390/ijms17020174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S. J., Song X. Y., He M., Yu S. B. (2016). Effect of TGF-β1/SDF-1/CXCR4 signal on BM-MSCs homing in rat heart of ischemia/perfusion injury. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 20 899–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Chopp M., Zhang Z. G., Katakowski M., Xin H., Qu C., et al. (2017). Systemic administration of cell-free exosomes generated by human bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells cultured under 2D and 3D conditions improves functional recovery in rats after traumatic brain injury. Neurochem. Int. 111 69–81. 10.1016/j.neuint.2016.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]