This study attempts to determine if there is an association between internalizing symptoms and disorders and migraine in children and adolescents.

Key Points

Question

Is there an association between anxiety and depressive symptoms and disorders and migraine in children and adolescents, and if so, what is its magnitude?

Findings

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 80 observational studies, we found a significant association between anxiety and depressive symptoms and disorders, mixed internalizing symptoms and disorders, and migraine in children and adolescents (with moderate to large effect sizes for each association).

Meaning

In this study, children and adolescents with migraine were more likely to experience internalizing symptoms and disorders compared with their peers without migraine; screening for these symptoms and disorders in clinical practice may be beneficial.

Abstract

Importance

Though it is presumed that children and adolescents with migraine are at risk of internalizing symptoms and disorders, high-level summative evidence to support this clinical belief is lacking.

Objective

To determine if there is an association between internalizing symptoms and disorders and migraine in children and adolescents.

Data Sources

A librarian-led, peer-reviewed search was performed using MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, and CINAHL databases (inception to March 28, 2022).

Study Selection

Case-control, cohort, and cross-sectional studies on the association between internalizing symptoms and disorders and migraine in children and adolescents 18 years or younger were eligible.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two investigators independently completed abstract and full-text screening, data extraction, and quality appraisal using the Newcastle-Ottawa scales. Studies were pooled with random-effects meta-analyses using standardized mean differences (SMD) or odds ratios (OR) with 95% CIs. Where sufficient data for pooling were unavailable, studies were described qualitatively.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was migraine diagnosis; additional outcomes included migraine outcomes and incidence. Associations between these outcomes and internalizing symptoms and disorders were evaluated.

Results

The study team screened 4946 studies and included 80 studies in the systematic review. Seventy-four studies reported on the association between internalizing symptoms and disorders and migraine, and 51 studies were amenable to pooling. Meta-analyses comparing children and adolescents with migraine with healthy controls showed: (1) an association between migraine and anxiety symptoms (SMD, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.64-1.63); (2) an association between migraine and depressive symptoms (SMD, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.46-0.87); and (3) significantly higher odds of anxiety disorders (OR, 1.93, 95% CI, 1.49-2.50) and depressive disorders (OR, 2.01, 95% CI, 1.46-2.78) in those with, vs without, migraine. Stratification of results did not reveal differences between clinical vs community/population-based samples and there was no evidence of publication bias. Twenty studies assessing the association between internalizing symptoms or disorders and migraine outcomes (n = 18) or incident migraine (n = 2) were summarized descriptively given significant heterogeneity, with minimal conclusions drawn.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, children and adolescents with migraine were at higher risk of anxiety and depression symptoms and disorders compared with healthy controls. It may be beneficial to routinely screen children and adolescents with migraine for anxiety and depression in clinical practice. It is unclear whether having anxiety and depressive symptoms or disorders has an affect on migraine outcomes or incidence.

Introduction

One in 10 children and adolescents experience migraine1,2 and, across the life span, it is the second most prevalent and disabling disease worldwide.3 The optimal management of migraine in children and adolescents comprises a multimodal approach that combines evidence-based acute treatment, preventive treatment where indicated, education, identification, and treatment of comorbid disorders.4,5

Internalizing symptoms, defined as an individual’s tendency to react to stress with internal processes (eg, anxiety and depressive symptoms),6 are thought to be elevated in children and adolescents with migraine,7,8 though high-level summative evidence for this clinical belief is lacking. Also, it is unclear whether children and adolescents with migraine are at higher risk of having internalizing disorders, whereby the level of internalizing symptoms meet criteria for a clinical psychiatric disorder (eg, anxiety or depressive disorder) compared with their peers.7,9 Although a few published systematic reviews and meta-analyses have aimed to address these questions,10,11,12,13,14 they have either been too limited (eg, including studies using a particular measurement instrument or clinical population)10,12 or too broad in their scope (eg, including studies with heterogeneous populations, such as children and adolescents with a variety of headache disorders) to draw definite conclusions in children and adolescents with migraine.13,14

To address this gap in the literature, we completed a systematic review and meta-analysis that aimed to estimate the association between internalizing symptoms and disorders and the outcome of migraine in children and adolescents. We hypothesized that: (1) migraine would be strongly associated with internalizing symptoms or migraine would be modestly associated with internalizing disorders; (2) internalizing symptoms would be associated with poorer outcomes in children and adolescents with migraine; and (3) internalizing symptoms would be a risk factor for incident migraine.

Methods

A detailed protocol for this study has been previously published15 and registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO 161788). This article adheres to the reporting guidelines from the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) reporting guidelines16 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines.17

Objectives

We aimed to determine if there is an association between internalizing symptoms and disorders and migraine in children and adolescents. We also aimed to: (1) determine if internalizing symptoms are associated with outcomes in children and adolescents with migraine (eg, higher attack frequency) and (2) determine if there is an association between internalizing symptoms and incident migraine in children and adolescents.

Eligibility Criteria

We included case-control, cohort, and cross-sectional studies assessing the association between internalizing symptoms and/or disorders and migraine in children and adolescents 18 years or younger. Eligible studies assessed symptoms and disorders on the spectrum of anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, and trauma- and stressor-related disorders, as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition). Abstracts of otherwise eligible studies were included. We excluded studies that had participants older than 18 years if the data for the younger participants were not reported separately, and we excluded studies with other headache disorders if the data for the migraine group was not reported separately. Studies were not restricted by language.

Information Sources and Search Strategy

MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, and CINAHL were searched from inception to March 28, 2022. Reference lists of included studies and review articles were searched for additional information sources. A research librarian with experience in systematic reviews drafted the search strategy, which was peer reviewed by a second research librarian using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies standard.18,19 The search strategies used for each database are in the published protocol.15

Study Selection

During the first screening phase, 2 independent screeners reviewed each abstract using the Abstrackr software.20 Disagreements were initially present for 1296 of the abstracts (26.2%). An expert screener (S.L.O.) then screened all conflicts and made final inclusion decisions. For the second eligibility screens, the full-text manuscripts were downloaded into Mendeley. Two independent screeners reviewed the full texts and made inclusion decisions. Where discrepancies arose, an expert screener (S.L.O.) made the final decision.

Data Collection

Data extraction was carried out as per a priori plans15 by 2 researchers using standardized forms. Where raw data were available, data for the most adjusted associations were extracted and entered into a master Excel file, which was reviewed by 2 researchers.

Risk of Bias Assessment

For case-control and cohort studies, the validated Newcastle-Ottawa scale was used to rate risk of bias. For cross-sectional studies, an adapted version of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale was used, as per Loney et al.21 For each study, 2 researchers independently rated risk of bias using standardized data collection tables published in the study protocol.15

Synthesis of Results

For our primary objective, studies reporting raw data on the association between internalizing symptoms or disorders and migraine were pooled together in stratified meta-analyses. In cases where the raw data were unpublished, the authors were contacted on 2 occasions, 2 weeks apart, with a request to share the raw data. Where not available after contact, data were summarized descriptively. Data were stratified based on whether internalizing symptoms or internalizing disorders were assessed. Data were also stratified based on the control group (ie, children and adolescents with no headache vs children and adolescents with other headache disorders).

For the meta-analyses, in the case of continuous outcomes, group means and standard deviations from the studies were used to generate standardized mean difference (SMD) estimates with 95% CIs, with SMD estimates 0.5 or less considered small, more than 0.5 to 0.8 considered moderate, and more than 0.8 considered large in magnitude. For dichotomous outcomes, the most adjusted data available were used to generate odds ratios (OR) and 95% CIs (ie, we selected adjusted ORs and their 95% CIs, if unavailable, we used unadjusted ORs and their 95% CIs and where only raw proportion data were available, we hand calculated unadjusted ORs and 95% CIs). Estimates of the association between internalizing symptoms or disorders and migraine were generated using random effects meta-analyses (DerSimonian and Laird method). Statistical heterogeneity was measured using the I2 statistic.

Publication Bias Assessment

For the studies in the meta-analysis, the Begg test was used to assess publication bias (P < .05 considered significant). P values were 2-tailed.

Results

Study Selection

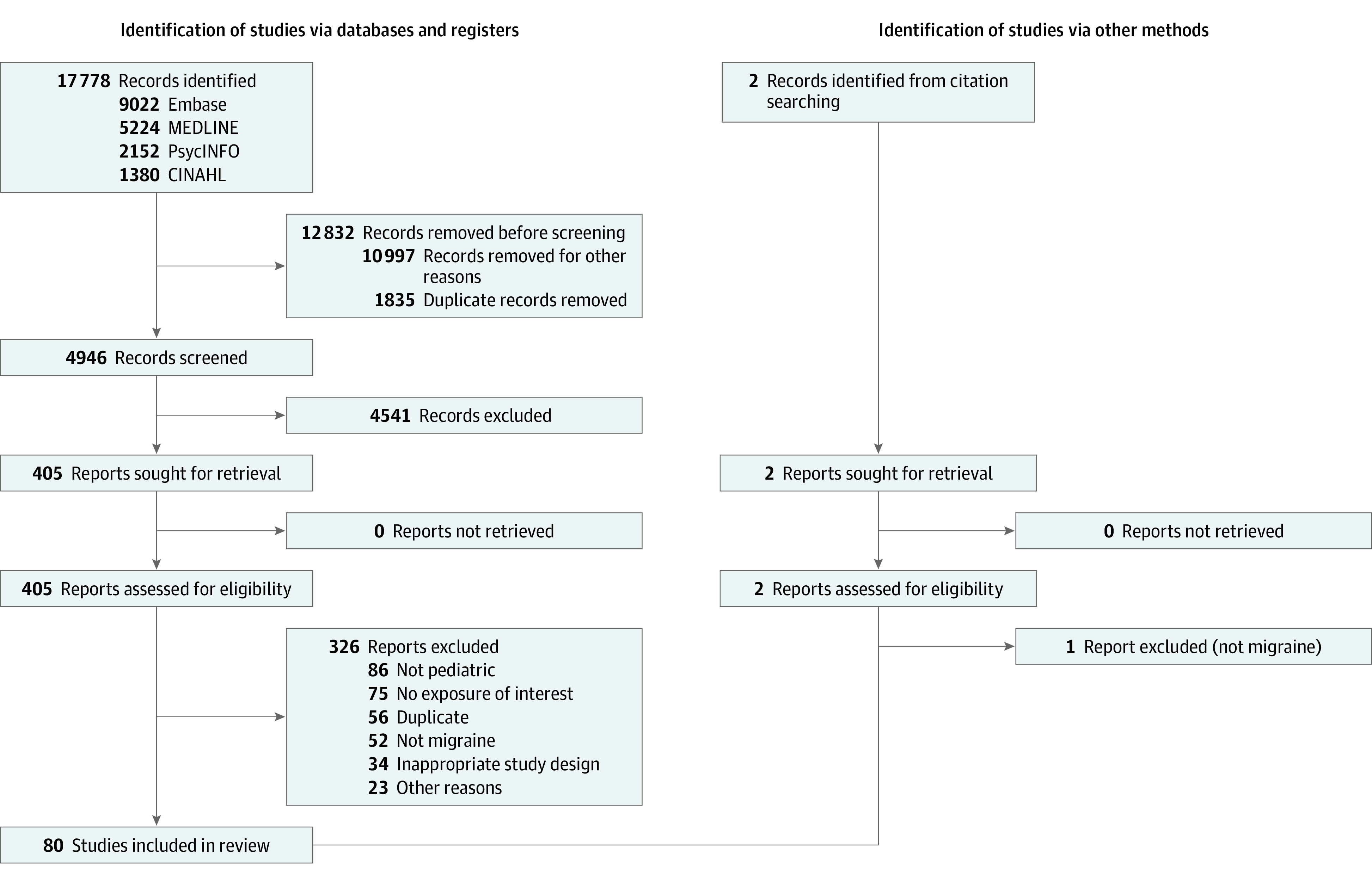

We screened 4946 studies, of which 4866 were excluded, for a final of 80 included studies (Figure 1). Of note, the included studies assessed anxiety and depressive symptoms and/or disorders, or combined internalizing symptoms and/or disorders; none assessed the association between trauma- and stressor-related symptoms and/or disorders and migraine.

Figure 1. PRISMA Diagram.

Study Characteristics

Characteristics of included studies are summarized in Table 1 and the Supplement includes more detailed summary of studies’ tables (eTables 1, 2, and 3 in the Supplement). Seventy-four studies reported on the association between internalizing symptoms, internalizing disorders, and migraine,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95 and 51 of these studies22,23,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,36,38,40,42,45,46,48,51,53,54,55,56,60,61,63,64,65,67,69,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,82,83,84,86,87,88,89,90,92,95 were amenable to pooling of at least some of their data in meta-analyses, while the remaining study results were summarized descriptively (Table 1 and Figure 2). Eighteen studies assessed the association between internalizing symptoms or disorders and a migraine outcome.27,29,31,36,46,47,64,68,69,83,85,95,96,97,98,99,100 Only 2 studies reported on the association between internalizing symptoms or disorders and incident migraine.40,101 Given significant outcome heterogeneity for the migraine outcomes and incidence studies, meta-analysis was not appropriate and these studies were summarized descriptively.

Table 1. Characteristics of Included Studies.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Association studies | Migraine outcomes studies | Incidence studies | ||

| In meta-analysis | Not in meta-analysis | |||

| No. of total studies | 51 | 29 | 18 | 2 |

| Study design | ||||

| Cross-sectional | 21 (41.2) | 10 (34.5) | 8 (44.4) | 0 |

| Case-control | 28 (54.9) | 17 (58.6) | 8 (44.4) | 0 |

| Cohort | 2 (3.9) | 2 (6.9) | 2 (11.2) | 2 (100.0) |

| Setting | ||||

| Clinical | 34 (66.7) | 19 (65.5) | 15 (83.3) | 0 |

| Community | 5 (10.0) | 1 (3.5) | 1 (5.6) | 2 (100.0) |

| Population-based | 8 (15.7) | 3 (10.3) | 0 | 0 |

| Not reported | 4 (7.8) | 6 (20.7) | 2 (11.1) | 0 |

| Sample size | ||||

| <50 | 4 (7.8) | 5 (17.2) | 0 | 0 |

| 50-100 | 16 (31.4) | 8 (27.6) | 11 (61.1) | 0 |

| >100-1000 | 20 (39.2) | 10 (34.5) | 4 (22.2) | 0 |

| >1000 | 11 (21.6) | 6 (20.7) | 3 (16.7) | 2 (100.0) |

| Ages | ||||

| <12 y | 4 (7.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ≥12-18 y | 11 (21.6) | 7 (24.1) | 2 (11.2) | 2 (100.0) |

| Mixed ages | 36 (70.6) | 22 (75.9) | 16 (88.8) | 0 |

| Sex distribution | ||||

| <50% Female | 11 (21.6) | 5 (17.2) | 4 (22.2) | 1 (50.0) |

| 50%-60% Female | 21 (41.2) | 8 (27.7) | 7 (38.9) | 1 (50) |

| >60%-70% Female | 8 (15.7) | 0 | 3 (16.7) | 0 |

| >70% Female | 8 (15.7) | 5 (17.2) | 3 (16.7) | 0 |

| Not reported | 3 (5.9) | 11 (37.9) | 1 (5.5) | 0 |

| Outcome type | ||||

| Episodic migraine only | 5 (10.0) | 5 (17.2) | 1 (5.6) | 0 |

| Chronic migraine only | 4 (7.8) | 1 (3.5) | 1 (5.6) | 1 (50.0) |

| Mixed episodic and chronic migraine | 17 (33.3) | 6 (20.7) | 9 (50) | 1 (50.0) |

| Not reported | 25 (49.0) | 17 (58.6) | 7 (38.8) | 0 |

| Outcome ascertainment | ||||

| ICHD criteria | 43 (84.3) | 14 (48.3) | 15 (83.3) | 1 (50.0) |

| Not ICHD criteria | 6 (11.8) | 7 (24.1) | 2 (11.2) | 1 (50.0) |

| Not reported | 2 (3.9) | 8 (27.6) | 1 (5.5) | 0 |

| Results adjusted for important covariates (eg, age, sex) | ||||

| Yes | 13 (25.5) | 5 (17.2) | 7 (38.9) | 2 (100.0) |

| No | 38 (74.5) | 24 (82.8) | 11 (61.1) | 0 |

| Study quality rating | ||||

| High (>80%) | 12 (23.5) | 1 (3.4) | 2 (11.2) | 1 (50.0) |

| Moderate (50%-80%) | 31 (60.8) | 14 (48.3) | 12 (66.6) | 1 (50.0) |

| Low (<50%) | 8 (15.7) | 14 (48.3) | 4 (22.2) | 0 |

| Exposure type(s) measureda | ||||

| Anxiety symptoms | 21 | 10 | 9 | 0 |

| Anxiety disorders | 19 | 6 | 3 | 0 |

| Depressive symptoms | 21 | 15 | 9 | 0 |

| Depressive disorders | 20 | 8 | 2 | 1 |

| Mixed-internalizing symptoms | 13 | 5 | 2 | 1 |

| Mixed-internalizing disorders | 10 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Exposure assessment toolb | ||||

| Symptom level | ||||

| Validated questionnaire | ||||

| Anxiety symptoms | 20 (95.2) | 10 (100.0) | 8 (88.9) | NA |

| Depressive symptoms | 21 (100.0) | 14 (93.3) | 8 (88.9) | NA |

| Mixed-internalizing symptoms | 13 (100.0) | 5 (100.0) | 2 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) |

| Unvalidated tool | ||||

| Anxiety symptoms | 1 (4.8) | 0 | 1 (11.1) | NA |

| Depressive symptoms | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 1 (11.1) | NA |

| Mixed-internalizing symptoms | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Disorder level | ||||

| Validated diagnostic interview | ||||

| Anxiety disorders | 12 (63.1) | 3 (50.0) | 1 (33.3) | NA |

| Depressive disorders | 12 (60.0) | 3 (37.5) | 1 (50.0) | 0 |

| Mixed-internalizing disorders | 0 | 1 (33.3) | 1 (50.0) | NA |

| Validated questionnaire cutoff score | ||||

| Anxiety disorders | 6 (31.6) | 1 (16.7) | 0 | NA |

| Depressive disorders | 7 (35.0) | 2 (25.0) | 0 | 1 (100.0) |

| Mixed-internalizing disorders | 10 (100.0) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (50.0) | NA |

| Other | ||||

| Anxiety disorders | 1 (5.3) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | NA |

| Depressive disorders | 1 (5.0) | 2 (25.0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 |

| Mixed-internalizing disorders | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Exposure-outcome association (most adjusted results) c | ||||

| Positive association | ||||

| Anxiety symptoms | 13 (61.9) | 4 (40.0) | 3 (33.3) | NA |

| Anxiety disorders | 8 (42.1) | 2 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | NA |

| Depressive symptoms | 12 (57.1) | 11 (73.3) | 7 (87.5) | NA |

| Depressive disorders | 4 (20.0) | 3 (37.5) | 0 | 1 (100.0) |

| Mixed-internalizing symptoms | 12 (92.3) | 5 (100.0) | 2 (100.0) | 0 |

| Mixed-internalizing disorders | 8 (80.0) | 0 | 1 (50.0) | NA |

| No association | ||||

| Anxiety symptoms | 5 (23.9) | 6 (60.0) | 4 (44.4) | NA |

| Anxiety disorders | 2 (10.5) | 1 (16.7) | 0 | NA |

| Depressive symptoms | 6 (28.6) | 3 (20.0) | 1 (12.5) | NA |

| Depressive disorders | 4 (20.0) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (50.0) | 0 |

| Mixed-internalizing symptoms | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100.0) |

| Mixed-internalizing disorders | 0 | 1 (33.3) | 1 (50.0) | NA |

| Negative association | ||||

| Anxiety symptoms | 0 | 0 | 1 (11.1) | NA |

| Anxiety disorders | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Depressive symptoms | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Depressive disorders | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mixed-internalizing symptoms | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mixed-internalizing disorders | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Measured, association not reported | ||||

| Anxiety symptoms | 3 (14.2) | 0 | 1 (22.2) | NA |

| Anxiety disorders | 9 (47.4) | 3 (50.0) | 1 (33.3) | NA |

| Depressive symptoms | 3 (14.3) | 1 (6.7) | 0 | NA |

| Depressive disorders | 12 (60.0) | 4 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 |

| Mixed-internalizing symptoms | 1 (7.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mixed-internalizing disorders | 2 (20.0) | 2 (66.7) | 0 | NA |

Abbreviations: ICHD, International Classification of Headache Disorders; NA, not applicable.

Because many studies reported on multiple exposure types, percentage not given.

Percentage reflects proportion of studies measuring a given exposure type using a given type of exposure assessment tool over the total number of studies measuring that exposure type.

Percentage reflects proportion of studies reporting a given association direction for a given type of exposure over the total number of studies measuring that exposure type. Here, a positive association denotes: (1) for association studies, that higher exposure to internalizing symptoms/disorders was associated with migraine diagnosis; (2) for migraine outcomes studies, that higher exposure to internalizing symptoms/disorders was associated with worse outcomes; and (3) for incidence studies, that higher exposure to internalizing symptoms/disorders was associated with higher incidence of migraine. Associations that are marked as not reported were either not reported because hypothesis testing was not done, or the migraine group was not compared with a healthy control group (eg, compared with other headache control), or to any control group.

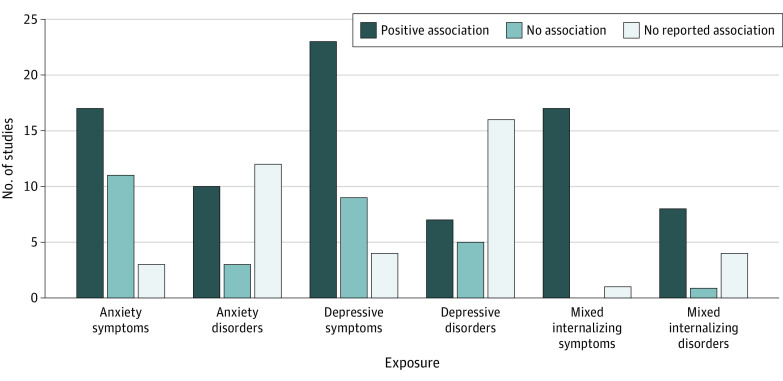

Figure 2. Direction of Exposure-Outcome Associations for Studies.

Illustration of the direction of the exposure-outcome association observed in the association studies and includes studies in both in the meta-analysis and not in the meta-analysis.

Risk of Bias Within Studies

The quality ratings of the studies are summarized in Table 1, and detailed quality ratings are available in eTables 4, 5, and 6 in the Supplement. Overall, 13 of 80 studies (16.3%) were rated as high quality (more than 80% score on the quality scales), 46 of 80 studies (57.5%) were rated as moderate quality (50% to 80% range score on the scales), and 21 of 80 studies (26.2%) were rated as low quality (less than 50% score on the scales). The quality of the studies not in the meta-analysis was poorer as compared with the studies in the meta-analysis (48.3% of the studies not in the meta-analysis vs 15.7% of the studies in the meta-analysis had low quality ratings).

Association Studies in the Meta-analysis

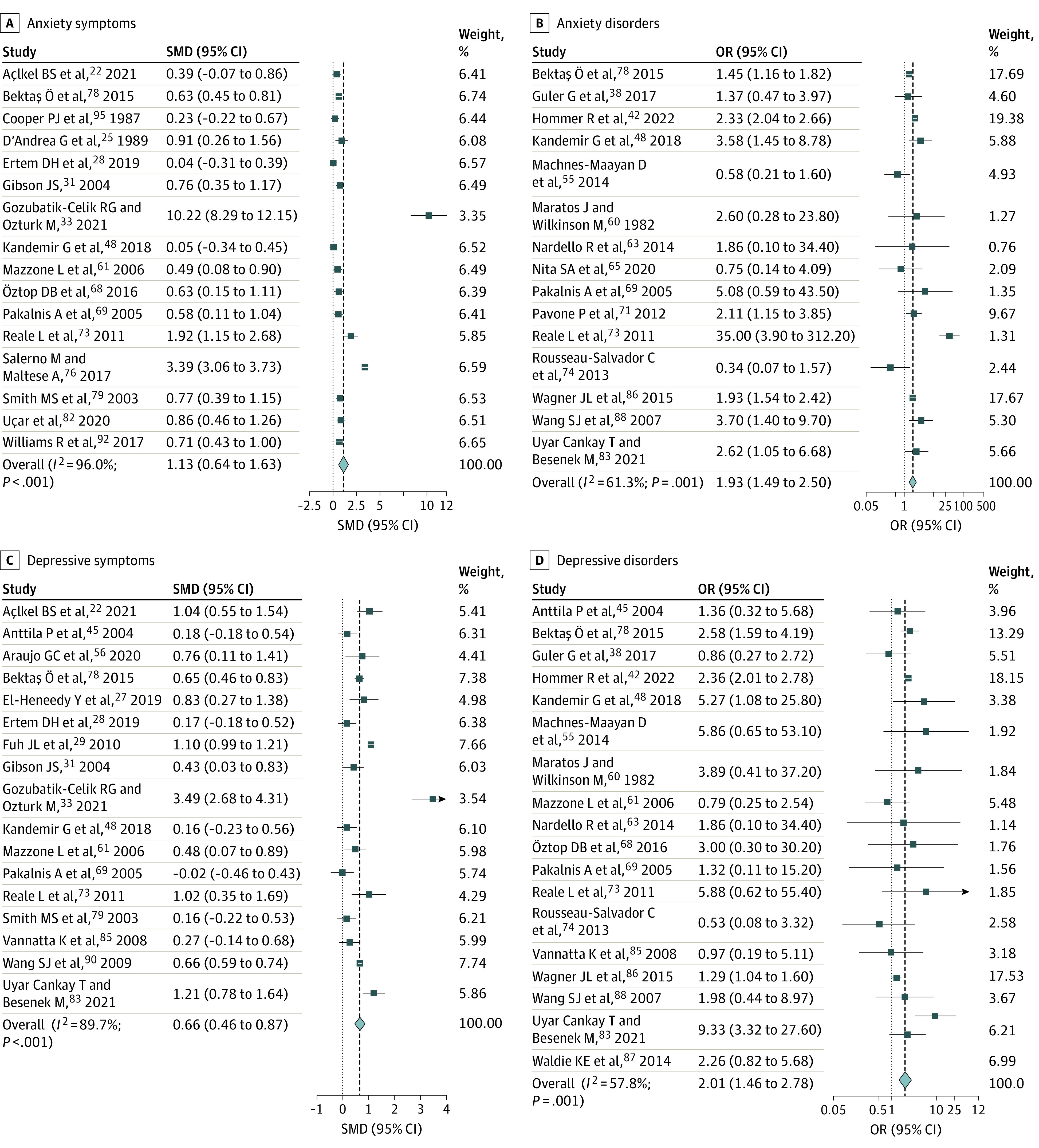

As illustrated in Figure 3, anxiety symptoms were significantly higher in children and adolescents with migraine as compared with controls, with a large effect size observed (n = 16 studies; SMD, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.64-1.63; I2 = 96%). The odds of having an anxiety disorder were higher among children and adolescents with migraine as compared with controls (n = 15 studies; OR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.49-2.50; I2 = 61.3%).

Figure 3. Results of Meta-analyses Comparing Migraine With Healthy Controls.

Forest plots illustrating pooled results of studies comparing migraine vs healthy control samples. Weights are from random effects.

Depressive symptoms were also significantly higher in children and adolescents with migraine compared with controls, with a moderate effect size (n = 17 studies; SMD, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.46-0.87; I2 = 89.7%). Moreover, the odds of having a depressive disorder were higher among children and adolescents with migraine as compared with controls (n = 18 studies; OR, 2.01, 95% CI, 1.46-2.78; I2 = 57.8%). Similar results were seen in studies that pooled internalizing symptoms or disorders together: children and adolescents with migraine had significantly higher internalizing symptoms than controls, with a large effect size observed (n = 10 studies; SMD, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.66-1.09; I2 = 63.9%) and also had higher odds of experiencing mixed internalizing disorders than controls (n = 9 studies that reported on pooled prevalence of anxiety and/or depressive disorders; OR, 4.69; 95% CI, 3.08-7.14; I2 = 82.2%; eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

When children and adolescents with migraine were compared with children and adolescents with other headache disorders (eg, tension-type headache, new daily persistent headache),22,23,28,29,30,32,33,36,40,42,45,46,51,53,54,55,61,67,71,72,74,75,78,83,84 no significant differences emerged for internalizing symptoms nor disorders between the 2 groups (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

When studies were stratified by setting, whereby clinical samples were compared with community or population-based samples, no differences were seen in the effect sizes for anxiety or depressive symptoms or disorders, though studies with recruitment from other settings (mostly unreported settings) had different effect-size magnitudes, and in some cases the cell sizes were small, which complicates interpretation of the stratified results (Table 2). For mixed internalizing symptoms, there was a large vs moderate effect size (SMD, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.77-1.33 vs SMD, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.22-0.99) and a higher odds of mixed internalizing disorders (OR, 8.02; 95% CI, 4.77-13.49 vs. OR, 3.76; 95% CI, 2.37-5.97) when comparing clinical with community or population-based samples. In sensitivity analyses where studies with outlying values were excluded, the results did not change significantly (eTable 7 in the Supplement). There was no evidence of publication bias (Begg tests all P > .05).

Table 2. Stratification of Meta-analysis Results by Setting.

| Studies | Stratification by setting | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure type | Control group | Measure | Studies, No. | Clinical | Community/population-based | Unknown setting |

| Anxiety symptoms | Healthy controls | SMD (95% CI) | 16 | 0.88 (0.50-1.27) | 0.63 (0.45-0.81) | 3.39 (3.06-3.73) |

| No. | NA | NA | NA | 14 | 1a | 1a |

| Anxiety disorders | Healthy controls | OR (95% CI) | 15 | 2.02 (1.25-3.24) | 2.04 (1.33-3.13) | 1.16 (0.47-2.85) |

| No. | NA | NA | NA | 10 | 3 | 2a |

| Depressive symptoms | Healthy controls | SMD (95% CI) | 17 | 0.71 (0.36-1.05) | 0.68 (0.39-0.98) | NA |

| No. | NA | NA | NA | 13 | 4 | NA |

| Depressive disorders | Healthy controls | OR (95% CI) | 18 | 2.19 (1.17-4.09) | 2.36 (2.03-2.74) | 0.95 (0.33-2.78) |

| No. | NA | NA | NA | 11 | 5 | 2a |

| Internalizing symptoms | Healthy controls | SMD (95% CI) | 10 | 1.05 (0.77-1.33) | 0.61 (0.22-0.99) | NA |

| No. | NA | NA | NA | 7 | 3 | NA |

| Internalizing disorders | Healthy controls | OR (95% CI) | 9 | 8.02 (4.77-13.49) | 3.76 (2.37-5.97) | NA |

| No. | NA | NA | NA | 4 | 5 | NA |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; NA, not applicable; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Small number of studies in cell make interpretation of stratified results more challenging.

Association Studies Not in the Meta-analysis

Results of the 29 studies that included data that were not amenable to pooling are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 3. Comparing studies in the meta-analysis vs those not in the meta-analysis, there were similar proportions of studies that found positive associations between internalizing symptoms and disorders and migraine as compared with no significant associations. For studies assessing the association between migraine and anxiety symptoms, there was a discrepancy between the studies in the meta-analysis vs not in the meta-analysis, with a higher proportion of the studies not in the meta-analysis finding no association between anxiety symptoms and migraine as compared to the studies in the meta-analysis (60% vs 23.9%). A significant proportion of the studies assessing internalizing disorders that were not in the meta-analysis had no hypothesis testing (50% to 66.7%), and only reported disorder proportions among a migraine sample; minimal conclusions can be drawn about these results. Most of these studies were small and did not report sample size calculations; thus, it is unclear if they were powered to detect clinically meaningful effect sizes.

Studies Assessing Migraine Outcomes

Internalizing Symptoms and Outcomes in Children and Adolescents With Migraine

Of the 13 studies reporting on the association between migraine outcomes and internalizing symptoms in children and/or adolescents,27,29,46,68,83,85,95,96,97,98,99,100 10 were cross-sectional (Table 1).27,28,29,46,68,83,96,98,99,100 One of these studies assessed school functioning,46 4 measured migraine-specific disability scores,27,29,68,83 and the remaining 5 studies examined headache frequency and/or severity cross-sectionally.28,96,98,100 It is difficult to draw conclusions about the association between anxiety and depressive symptoms and migraine outcomes from these cross-sectional studies, as they were limited in number, had heterogeneous outcomes, and were minimally comparable.

Only 3 of the studies measuring the association between internalizing symptoms and migraine outcomes were longitudinal (length of follow-up ranging from 1 to 4 months; eTable 2 in the Supplement).85,95,97 All of these assessed the association between internalizing symptoms and the outcome of headache frequency, and each found a positive association, whereby higher anxiety,95 depressive,85,97 and mixed internalizing symptoms85 were associated with higher headache frequencies at follow-up in children and adolescents with migraine.

Internalizing Disorders and Outcomes in Children and Adolescents With Migraine

Five heterogeneous studies reported on the association between internalizing disorders and outcomes in children and adolescents with migraine.31,36,47,64,69 Mixed internalizing disorders were associated with lower quality of life,31 as well as higher headache frequencies,31 and anxiety disorders were associated with higher headaches frequencies64 and a higher risk of headache persistence at 8-year follow up36 in single studies. In contrast, 1 study found no association between baseline depressive disorders and headache persistence at 8-year follow up,36 and another study found no association between having any psychiatric comorbidity and treatment response at 3-month follow up.69 Additionally, 1 study found that, among children and adolescents hospitalized for migraine, those with any psychiatric comorbidity were more likely to receive medication, have longer lengths of stay, and have higher hospitalization costs compared with those without any psychiatric comorbidity.47

Incidence Studies

Two population-based or community-based studies reported on the outcome of incident migraine40,101 and found a positive association between baseline internalizing symptoms and incident migraine at follow-up in adolescence (length of follow-up ranging from 2 to 7 years; eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Discussion

The results of our systematic review and meta-analyses demonstrate that children and adolescents with migraine are more likely to have anxiety and depressive symptoms and anxiety and depressive disorders (approximately double the odds), as compared with healthy controls. With regards to whether the presence of internalizing symptoms or disorders influences migraine outcomes, few studies (n = 18) were identified and heterogeneity in their design and measured outcomes precluded both statistical pooling and drawing meaningful conclusions. One observation of note was that of the 8 studies that assessed the association between depressive symptoms and migraine outcomes, 87.5% (n = 7 of 8) reported that higher depressive symptoms were associated with worse migraine outcomes, indicative of high homogeneity with regards to the presence and directionality of the association. This observation suggests that depressive symptoms may be associated with worse migraine-related outcomes, though without the ability to pool the data and with heterogeneous outcomes across studies, more work is required prior to drawing this conclusion definitively. It is also unclear whether treatment of depressive symptoms (or any comorbid internalizing symptoms or disorders) can influence migraine-specific outcomes. Next, only 2 studies assessed the association between baseline internalizing symptoms and risk of incident migraine, and both studies showed that baseline internalizing symptoms were associated with a higher risk of incident migraine in community/population-based samples of adolescents. The small number of incidence studies and their heterogeneous designs precludes any strong conclusions from being drawn from these studies. Additionally, no studies were identified that assessed the association between trauma- and stressor-related symptoms or disorders and migraine, despite inclusion of these in our aims and search strategy. This represents a substantial gap in the pediatric migraine literature, especially given that work in the broader pediatric pain literature has identified that trauma- and stressor-related symptoms and disorders are associated with chronic pain and worse outcomes in children and adolescents.102,103,104

The association between migraine and anxiety and depressive symptoms and disorders is likely bidirectional and multifactorial.8 First, environmental risk factors are an important link to consider. The experience of pain and internalizing symptoms may result in mutually reinforcing behaviors, such as reduced sleep and withdrawal from activities, and mutually reinforcing cognitive patterns, such as negativity bias and attention bias.102 Additionally, exposure to environmental adversity (eg, family-level stressors and adverse childhood experiences) during critical periods of brain development may increase the risk of developing both anxiety and depressive symptoms and disorders, as well as migraine.40,105,106 There is also genetic overlap between migraine, anxiety, and depression, with shared genetic factors having been identified in prior work.107,108,109,110 Though it is clear that the association between internalizing symptoms, disorders, and migraine is complex, bidirectional, and driven by both environmental and genetic factors, there is work to be done in this area. Untangling the reasons for why these comorbidities exist and how they influence each other presents an opportunity to better understand disease etiology from a biopsychosocial perspective and has the potential to add to the treatment landscape.

Considering the associations identified between depressive and anxiety symptoms and disorders and migraine, clinicians should screen for these in clinical practice. Formal, validated screening tools can be used to supplement the clinical assessment. As an example, the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System111 is a validated system of measurement tools that are freely available and that have been translated in several languages.

Limitations

There are several strengths and limitations to this work. To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive systematic review with meta-analyses that included all studies on the association between depressive and anxiety symptoms and disorders and migraine in children and adolescents. We included studies in all languages, and studies that had, and did not have, adequate data for meta-analysis, to provide an unbiased overview of the available literature. We followed PRISMA and MOOSE reporting guidelines and the process described in our a priori published protocol. We used random-effects meta-analyses to pool the association data that was amenable to pooling and stratification and sensitivity analyses to ensure that the results were robust, which improves confidence in the effect size estimates. Limitations include our inability to further stratify results based on important covariates, such as headache frequency (eg, episodic vs chronic migraine) and sex; this is a reflection of inadequate stratified reporting in the original studies. Although we used the most adjusted estimates available for our meta-analyses and descriptive synthesis of the data, most included studies (66 of 80 [82.5%]) reported only unadjusted associations, thereby increasing the risk of bias due to unmeasured confounders. Additionally, over a quarter (21 of 80 [26.3%]) of the studies had low quality ratings, and there are certainly various types of bias present in the pooled review on our risk of bias assessment.

Conclusions

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, children and adolescents with migraine had more depressive and anxiety symptoms, and higher odds of depressive and anxiety disorders, as compared with their peers without migraine. These results have critical implications for clinical practice, underscoring the need to screen all children and adolescents with migraine for anxiety and depression. It remains unclear if the presence of anxiety and depressive symptoms or disorders has any effect on migraine-specific outcomes or risk of incident migraine. Future work should address these questions and aim to determine whether trauma- and stressor-related symptoms and disorders are associated with migraine in children and adolescents, as no studies on this topic were identified in our searches.

eTable 1. Summary of studies examining the association between migraine and anxiety and depressive symptoms/disorders (n=74)

eTable 2. Summary of studies examining migraine outcomes (n=18)

eTable 3. Summary of studies examining migraine incidence (n=2)

eTable 4. Risk of bias ratings for case-control studies

eTable 5. Risk of bias ratings for cross-sectional studies

eTable 6. Risk of bias ratings for cohort studies

eFigure 1. Results of meta-analyses comparing migraine to healthy controls for internalizing symptoms and disorders (presented in forest plots)

eFigure 2. Results of meta-analyses comparing migraine to other headache controls (presented in forest plots)

eTable 7. Sensitivity analyses with removal of outlying studies

References

- 1.Abu-Arafeh I, Razak S, Sivaraman B, Graham C. Prevalence of headache and migraine in children and adolescents: a systematic review of population-based studies. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52(12):1088-1097. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03793.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orr SL, Potter BK, Ma J, Colman I. Migraine and mental health in a population-based sample of adolescents. Can J Neurol Sci. 2017;44(1):44-50. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2016.402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, et al. ; GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators . Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789-1858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orr SL, Kabbouche MA, O’Brien HL, Kacperski J, Powers SW, Hershey AD. Paediatric migraine: evidence-based management and future directions. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14(9):515-527. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0042-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szperka C. Headache in children and adolescents. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2021;27(3):703-731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Psychological Association . Internalizing-externalizing. Accessed September 27, 2022. https://dictionary.apa.org/externalizing-internalizing

- 7.Ziplow JL, Buse DC. Comorbidities in children and adolescents. In: Gladstein J, Szperka C, Gelfand A, eds. Pediatric Headache. Elsevier; 2021:chap 8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dresler T, Caratozzolo S, Guldolf K, et al. ; European Headache Federation School of Advanced Studies (EHF-SAS) . Understanding the nature of psychiatric comorbidity in migraine: a systematic review focused on interactions and treatment implications. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):51. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-0988-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gelfand AA. Psychiatric comorbidity and paediatric migraine: examining the evidence. Curr Opin Neurol. 2015;28(3):261-264. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balottin U, Fusar Poli P, Termine C, Molteni S, Galli F. Psychopathological symptoms in child and adolescent migraine and tension-type headache: a meta-analysis. Cephalalgia. 2013;33(2):112-122. doi: 10.1177/0333102412468386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amouroux R, Rousseau-Salvador C. [Anxiety and depression in children and adolescents with migraine: a review of the literature]. Encephale. 2008;34(5):504-510. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2007.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruijn J, Locher H, Passchier J, Dijkstra N, Arts WF. Psychopathology in children and adolescents with migraine in clinical studies: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):323-332. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinquart M, Shen Y. Depressive symptoms in children and adolescents with chronic physical illness: an updated meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36(4):375-384. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huguet A, Tougas ME, Hayden J, et al. Systematic review of childhood and adolescent risk and prognostic factors for recurrent headaches. J Pain. 2016;17(8):855-873.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falla K, Ronksley P, Noel M, Orr SL. Internalizing symptoms in pediatric migraine: a systematic review protocol. Headache. 2020;60(4):761-770. doi: 10.1111/head.13778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008-2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS Peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40-46. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McGowan J, Sampson M, Lefebvre C. An evidence based checklist for the peer review of electronic search strategies (PRESS EBC). Evid Based Libr Inf Pract. 2010;5(1):149-154. doi: 10.18438/B8SG8R [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallace B, Small K, Brodley CE, Lau J, Trikalinos TA. Deploying an interactive machine learning system in an evidence-based practice center Accessed September 27, 2022. https://www.byronwallace.com/static/articles/wallace_ihi_2011_preprint.pdf

- 21.Loney PL, Chambers LW, Bennett KJ, Roberts JG, Stratford PW. Critical appraisal of the health research literature: prevalence or incidence of a health problem. Chronic Dis Can. 1998;19(4):170-176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Açlkel BS, Bilgiç A, Derin H, Eroǧlu A, Akça ÖF, Çaksen H. Comparison of children with migraine and those with tension-type headache for psychiatric symptoms and quality of life. J Pediatr Neurol. 2021;19(1):14-23. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1692138 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albanês Oliveira Bernardo A, Lys Medeiros F, Sampaio Rocha-Filho PA. Osmophobia and odor-triggered headaches in children and adolescents: prevalence, associated factors, and importance in the diagnosis of migraine. Headache. 2020;60(5):954-966. doi: 10.1111/head.13806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cunningham SJ, McGrath PJ, Ferguson HB, et al. Personality and behavioural characteristics in pediatric migraine. Headache. 1987;27(1):16-20. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1987.hed2701016.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D’Andrea G, Nertempi P, Ferro Milone F, Joseph R, Cananzi AR. Personality and memory in childhood migraine. Cephalalgia. 1989;9(1):25-28. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1989.901025.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donnelly TJ, Bott A, Bui M, et al. Common pediatric pain disorders and their clinical associations. Clin J Pain. 2017;33(12):1131-1140. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El-Heneedy Y, Bahnasy W, Elahwal S, Am R, Abohammar S. Psychiatric and sleep abnormalities in school age children with migraine. Egypt J Neurol Psychiat Neurosurg. 2019;55(16):1-6. doi: 10.1186/s41983-019-0065-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ertem DH, Bingol A, Ugurcan B, et al. The impact of parental attitudes toward children with primary headaches. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;24(4):767-775. doi: 10.1177/1359104519838571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fuh JL, Wang SJ, Lu SR, Liao YC, Chen SP, Yang CY. Headache disability among adolescents: a student population-based study. Headache. 2010;50(2):210-218. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01531.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galli F, D’Antuono G, Tarantino S, et al. Headache and recurrent abdominal pain: a controlled study by the means of the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL). Cephalalgia. 2007;27(3):211-219. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01271.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gibson JS. Determinants of impaired quality of life in children with recurrent headache. Accessed October 5, 2022. https://www.proquest.com/docview/305139572

- 32.Gladstein J, Holden EW. Chronic daily headache in children and adolescents: a 2-year prospective study. Headache. 1996;36(6):349-351. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1996.3606349.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gozubatik-Celik RG, Ozturk M. Evaluation of quality of life and anxiety disorder in children and adolescents with primary headache. Med Bull Haseki. 2021;59(2):167-171. doi: 10.4274/haseki.galenos.2021.6465 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andrasik F, Kabela E, Quinn S, Attanasio V, Blanchard EB, Rosenblum EL. Psychological functioning of children who have recurrent migraine. Pain. 1988;34(1):43-52. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90180-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guidetti V, Fornara R, Ottaviano S, Petrilli A, Seri S, Cortesi F. Personality inventory for children and childhood migraine. a case-controlled study. Cephalalgia. 1987;7(4):225-230. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1987.0704225.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guidetti V, Galli F, Fabrizi P, et al. Headache and psychiatric comorbidity: clinical aspects and outcome in an 8-year follow-up study. Cephalalgia. 1998;18(7):455-462. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1998.1807455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guidetti V, Salvi E, Lo Noce A, Antonelli A. Attachment, depression and anxiety in children and adolescents with migraine. Cephalalgia. 2013;33(suppl 1):175-176. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guler G, Kutuk MO, Toros F, Ozge A. The high level of psychiatric disorders associated with migraine or tension-type headache in adolescents. J Neurol Sci. 2017;34(4):312-321. doi: 10.24165/jns.10112.17 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gunalan S, Chapman CA, Champion P, et al. Migraine and non-migraine headaches in children and adolescents: a twin family case-control study of genetic influence, pain, and psychological associations. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2012;40:531-555. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hammond NG, Orr SL, Colman I. Early life stress in adolescent migraine and the mediational influence of symptoms of depression and anxiety in a Canadian cohort. Headache. 2019;59(10):1687-1699. doi: 10.1111/head.13644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heinrich M, Morris L, Gassmann G, Kröner-Herwig B. [Frequency and type of headache among children and adolescents—results of an epidemiological survey]. Aktuelle Neurol. 2007;34(8):457-463. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-970933 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hommer R, Lateef T, He JP, Merikangas K. Headache and mental disorders in a nationally representative sample of American youth. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;31(1):39-49. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01599-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huss D, Derefinko K, Milich R, Farzam F, Baumann R. Examining the stress response and recovery among children with migraine. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34(7):707-715. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Just U, Oelkers R, Bender S, et al. Emotional and behavioural problems in children and adolescents with primary headache. Cephalalgia. 2003;23(3):206-213. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2003.00486.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anttila P, Sourander A, Metsähonkala L, Aromaa M, Helenius H, Sillanpää M. Psychiatric symptoms in children with primary headache. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(4):412-419. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaczynski KJ, Claar RL, Lebel AA. Relations between pain characteristics, child and parent variables, and school functioning in adolescents with chronic headache: a comparison of tension-type headache and migraine. J Pediatr Psychol. 2013;38(4):351-364. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jss120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kafle M, Mirea L, Gage S. Association of psychiatric comorbidities with treatment and outcomes in pediatric migraines. Hosp Pediatr. 2022;12(3):e101-e105. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2021-006085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kandemir G, Hesapcioglu ST, Kurt ANC. What are the psychosocial factors associated mith migraine in the child? comorbid psychiatric disorders, family functioning, parenting style, or mom’s psychiatric symptoms? J Child Neurol. 2018;33(2):174-181. doi: 10.1177/0883073817749377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kashikar-Zuck S, Zafar M, Barnett KA, et al. Quality of life and emotional functioning in youth with chronic migraine and juvenile fibromyalgia. Clin J Pain. 2013;29(12):1066-1072. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3182850544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kroner JW, Sullivan SM, Aylward BS, O’Brien HL, Kabbouche MA, Hershey AD. The psychosocial impact of migraine in adolescents. Cephalalgia. 2013;33(suppl 1):177-178. doi: 10.1177/0333102413490487 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kröner-Herwig B, Gassmann J. Headache disorders in children and adolescents: their association with psychological, behavioral, and socio-environmental factors. Headache. 2012;52(9):1387-1401. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02210.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lateef T, Witonsky K, He J, Ries Merikangas K. Headaches and sleep problems in US adolescents: findings from the National Comorbidity Survey—Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Cephalalgia. 2019;39(10):1226-1235. doi: 10.1177/0333102419835466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Laurell K, Larsson B, Eeg-Olofsson O. Headache in schoolchildren: association with other pain, family history and psychosocial factors. Pain. 2005;119(1-3):150-158. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lucarelli E, Presicci A, Lecce P, et al. Psychiatric comorbidty and temperament profiles in children and adolescents with migraine and tension type headache. Gior Neuropsich Età Evol. 2009;29(1):23–32 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Machnes-Maayan D, Elazar M, Apter A, Zeharia A, Krispin O, Eidlitz-Markus T. Screening for psychiatric comorbidity in children with recurrent headache or recurrent abdominal pain. Pediatr Neurol. 2014;50(1):49-56. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Araujo GC, Dodd JN, Mar S. Cognitive and emotional functioning in pediatric migraine relative to healthy control subjects. Pediatr Neurol. 2020;111:35-36. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2020.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maleki N, Field A, Kurth T. Comorbidities in adolescent female migraineurs between 10 to 15: pointing to the brainstem? Headache. 2016;56(suppl 1):52-53. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mar SS, Nolan T, Benzinger T, Schwedt T, Schlaggar B, Larson-Priior L. Effect of chronic migraine on brain function in children. Cephalalgia. 2009;29(12):1360. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mar S, Schwedt T, Benzinger TL, et al. Chronic migraine and pediatric brain function: Investigation using resting state-functional connectivity MRI. Ann Neurol. 2010;68(S14):S132-S133. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maratos J, Wilkinson M. Migraine in children: a medical and psychiatric study. Cephalalgia. 1982;2(4):179-187. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1982.0204179.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mazzone L, Vitiello B, Incorpora G, Mazzone D. Behavioural and temperamental characteristics of children and adolescents suffering from primary headache. Cephalalgia. 2006;26(2):194-201. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.01015.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McGinley JS, Wirth RJ, Houts CR. Growth curves for headache research: a multilevel modeling perspective. Headache. 2019;59(7):1063-1073. doi: 10.1111/head.13545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nardello R, Autunnali S, Magno R, Fontana A, Mangano S. Comorbidity between pediatric headaches and psychiatric disorders. Headache. 2014. doi: 10.1111/head.12431 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nesterovskiy Y, Zavadenko N. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents with migraine. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(6)(suppl):1-296. doi: 10.1177/0333102415581304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nita SA, Teleanu RI, Bajenaru OA. Psychological evaluation in childhood migraine—steps towards a psychological profile of the child migraineur. Rom J Neurol Rev Rom Neurol. 2020;19(1):21-26. doi: 10.37897/RJN.2020.1.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Onofri A, Tozzi E. Neuropsychological disorders in migraineur children. Neurol Sci. 2019;40(suppl 2):S227-S227. doi: 10.1007/s10072-019-03957-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Arruda MA, Bigal ME. Behavioral and emotional symptoms and primary headaches in children: a population-based study. Cephalalgia. 2012;32(15):1093-1100. doi: 10.1177/0333102412454226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Öztop DB, Taşdelen BI, PoyrazoğLu HG, et al. Assessment of psychopathology and quality of life in children and adolescents with migraine. J Child Neurol. 2016;31(7):837-842. doi: 10.1177/0883073815623635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pakalnis A, Gibson J, Colvin A. Comorbidity of psychiatric and behavioral disorders in pediatric migraine. Headache. 2005;45(5):590-596. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2005.05113.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pakalnis A, Splaingard M, Splaingard D, Kring D, Colvin A. Serotonin effects on sleep and emotional disorders in adolescent migraine. Headache. 2009;49(10):1486-1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01392.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pavone P, Rizzo R, Conti I, et al. Primary headaches in children: clinical findings on the association with other conditions. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2012;25(4):1083-1091. doi: 10.1177/039463201202500425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rabner J, Kaczynski KJ, Simons LE, LeBel A. Pediatric headache and sleep disturbance: a comparison of diagnostic groups. Headache. 2018;58(2):217-228. doi: 10.1111/head.13207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Reale L, Guarnera M, Grillo C, Maiolino L, Ruta L, Mazzone L. Psychological assessment in children and adolescents with benign paroxysmal vertigo. Brain Dev. 2011;33(2):125-130. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2010.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rousseau-Salvador C, Amouroux R, Gooze R, et al. Risk factors of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents with headache: a cross-sectional study. Eur Rev Appl Psychol. 2013;63(5):295-302. doi: 10.1016/j.erap.2013.07.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rousseau-Salvador C, Amouroux R, Annequin D, Salvador A, Tourniaire B, Rusinek S. Anxiety, depression and school absenteeism in youth with chronic or episodic headache. Pain Res Manag. 2014;19(5):235-240. doi: 10.1155/2014/541618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Salerno M, Maltese A, Tripi G, et al. Separation anxiety in pediatric migraine without aura: a pilot study. Acta Med Mediter. 2017;33(4):621-625. doi: 10.19193/0393-6384_2017_4_092 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Salvadori F, Gelmi V, Muratori F. Present and previous psychopathology of juvenile onset migraine: a pilot investigation by Child Behavior Checklist. J Headache Pain. 2007;8(1):35-42. doi: 10.1007/s10194-007-0334-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bektaş Ö, Uğur C, Gençtürk ZB, Aysev A, Sireli Ö, Deda G. Relationship of childhood headaches with preferences in leisure time activities, depression, anxiety and eating habits: a population-based, cross-sectional study. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(6):527-537. doi: 10.1177/0333102414547134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Smith MS, Martin-Herz SP, Womack WM, Marsigan JL. Comparative study of anxiety, depression, somatization, functional disability, and illness attribution in adolescents with chronic fatigue or migraine. Pediatrics. 2003;111(4 Pt 1):e376-e381. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.e376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tereshchenko S, Shubina M. The development and well-being assessment (DAWBA) screening for psychiatric comorbidity in urban Siberian adolescents with tension-type headache and migraine. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(1)(suppl 1):254-255. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Trent H, Woods K, Ostrowski-Delahanty S, Victorio M. Impact of school placement on pediatric patients with migraine. Headache. 2020;60(suppl 1):87-88. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Uçar HN, Tekin U, Tekin E. Irritability and its relationships with psychological symptoms in adolescents with migraine: a case-control study. Neurol Sci. 2020;41(9):2461-2470. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04331-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Uyar Cankay T, Besenek M. Negative effects of accompanying psychiatric disturbances on functionality among adolescents with chronic migraine. BMC Neurol. 2021;21(1):97. doi: 10.1186/s12883-021-02119-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Valeriani M, Galli F, Tarantino S, et al. Correlation between abnormal brain excitability and emotional symptomatology in paediatric migraine. Cephalalgia. 2009;29(2):204-213. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01708.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vannatta K, Getzoff EA, Powers SW, Noll RB, Gerhardt CA, Hershey AD. Multiple perspectives on the psychological functioning of children with and without migraine. Headache. 2008;48(7):994-1004. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.01051.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wagner JL, Wilson DA, Smith G, Malek A, Selassie AW. Neurodevelopmental and mental health comorbidities in children and adolescents with epilepsy and migraine: a response to identified research gaps. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2015;57(1):45-52. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Waldie KE, Thompson JMD, Mia Y, Murphy R, Wall C, Mitchell EA. Risk factors for migraine and tension-type headache in 11 year old children. J Headache Pain. 2014;15(1):60. doi: 10.1186/1129-2377-15-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang SJ, Juang KD, Fuh JL, Lu S-R. Psychiatric comorbidity and suicide risk in adolescents with chronic daily headache. Neurology. 2007;68(18):1468-1473. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260607.90634.d6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Blaauw BA, Dyb G, Hagen K, et al. Anxiety, depression and behavioral problems among adolescents with recurrent headache: the Young-HUNT study. J Headache Pain. 2014;15(1):38. doi: 10.1186/1129-2377-15-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang SJ, Fuh JL, Juang KD, Lu SR. Migraine and suicidal ideation in adolescents aged 13 to 15 years. Neurology. 2009;72(13):1146-1152. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000345362.91734.b3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wilcox SL, Ludwick AM, Lebel A, Borsook D. Age- and sex-related differences in the presentation of paediatric migraine: a retrospective cohort study. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(6):1107-1118. doi: 10.1177/0333102417722570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Williams R, Leone L, Faedda N, et al. The role of attachment insecurity in the emergence of anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents with migraine: an empirical study. J Headache Pain. 2017;18(1):62. doi: 10.1186/s10194-017-0769-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yilmaz D, Balci Sezer O, Gokkurt D, Tiftik E. Depression level in children with migraine. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2017;21:e198. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2017.04.1058 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Braccili T, Montebello D, Verdecchia P, et al. Evaluation of anxiety and depression in childhood migraine. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 1999;3(1):37-39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cooper PJ, Bawden HN, Camfield PR, Camfield CS. Anxiety and life events in childhood migraine. Pediatrics. 1987;79(6):999-1004. doi: 10.1542/peds.79.6.999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Karlson CW, Litzenburg CC, Sampilo ML, et al. Relationship between daily mood and migraine in children. Headache. 2013;53(10):1624-1634. doi: 10.1111/head.12215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Orr SL, Turner A, Kabbouche MA, et al. Predictors of short-term prognosis while in pediatric headache care: an observational study. Headache. 2019;59(4):543-555. doi: 10.1111/head.13477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tarantino S, De Ranieri C, Dionisi C, et al. Clinical features, anger management and anxiety: a possible correlation in migraine children. J Headache Pain. 2013;14(1):39. doi: 10.1186/1129-2377-14-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tarantino S, di Stefano A, Messina V, et al. Role of maternal stress and alexithymia in children’s migraine severity and psychological profile. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(Supplement 1):109. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-1049-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tarantino S, Papetti L, Di Stefano A, et al. Anxiety, depression, and body weight in children and adolescents with migraine. Front Psychol. 2020;11:530911. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.530911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lu SR, Fuh JL, Wang SJ, et al. Incidence and risk factors of chronic daily headache in young adolescents: a school cohort study. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):e9-e16. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Vinall J, Pavlova M, Asmundson GJ, Rasic N, Noel M. Mental health comorbidities in pediatric chronic pain: a narrative review of epidemiology, models, neurobiological mechanisms and treatment. Children (Basel). 2016;3(4):40. doi: 10.3390/children3040040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Noel M, Wilson AC, Holley AL, Durkin L, Patton M, Palermo TM. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in youth with vs without chronic pain. Pain. 2016;157(10):2277-2284. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Pavlova M, Kopala-Sibley DC, Nania C, et al. Sleep disturbance underlies the co-occurrence of trauma and pediatric chronic pain: a longitudinal examination. Pain. 2020;161(4):821-830. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hammond NG, Colman I, Orr SL. Adverse childhood experiences and onset of migraine in Canadian adolescents: a cohort study. Headache. 2022;62(3):319-328. doi: 10.1111/head.14256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sahle BW, Reavley NJ, Li W, et al. The association between adverse childhood experiences and common mental disorders and suicidality: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. Published online February 27, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01745-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ligthart L, Nyholt DR, Penninx BWJH, Boomsma DI. The shared genetics of migraine and anxious depression. Headache. 2010;50(10):1549-1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01705.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yang Y, Ligthart L, Terwindt GM, Boomsma DI, Rodriguez-Acevedo AJ, Nyholt DR. Genetic epidemiology of migraine and depression. Cephalalgia. 2016;36(7):679-691. doi: 10.1177/0333102416638520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Stam AH, de Vries B, Janssens ACJW, et al. Shared genetic factors in migraine and depression: evidence from a genetic isolate. Neurology. 2010;74(4):288-294. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cbcd19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gonda X, Rihmer Z, Juhasz G, Zsombok T, Bagdy G. High anxiety and migraine are associated with the s allele of the 5HTTLPR gene polymorphism. Psychiatry Res. 2007;149(1-3):261-266. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Health Measure . PROMIS (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System). Accessed September 27, 2022. https://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/promis

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Summary of studies examining the association between migraine and anxiety and depressive symptoms/disorders (n=74)

eTable 2. Summary of studies examining migraine outcomes (n=18)

eTable 3. Summary of studies examining migraine incidence (n=2)

eTable 4. Risk of bias ratings for case-control studies

eTable 5. Risk of bias ratings for cross-sectional studies

eTable 6. Risk of bias ratings for cohort studies

eFigure 1. Results of meta-analyses comparing migraine to healthy controls for internalizing symptoms and disorders (presented in forest plots)

eFigure 2. Results of meta-analyses comparing migraine to other headache controls (presented in forest plots)

eTable 7. Sensitivity analyses with removal of outlying studies